Frequency and Effectiveness of Empirical Anti-TNF Dose Intensification in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

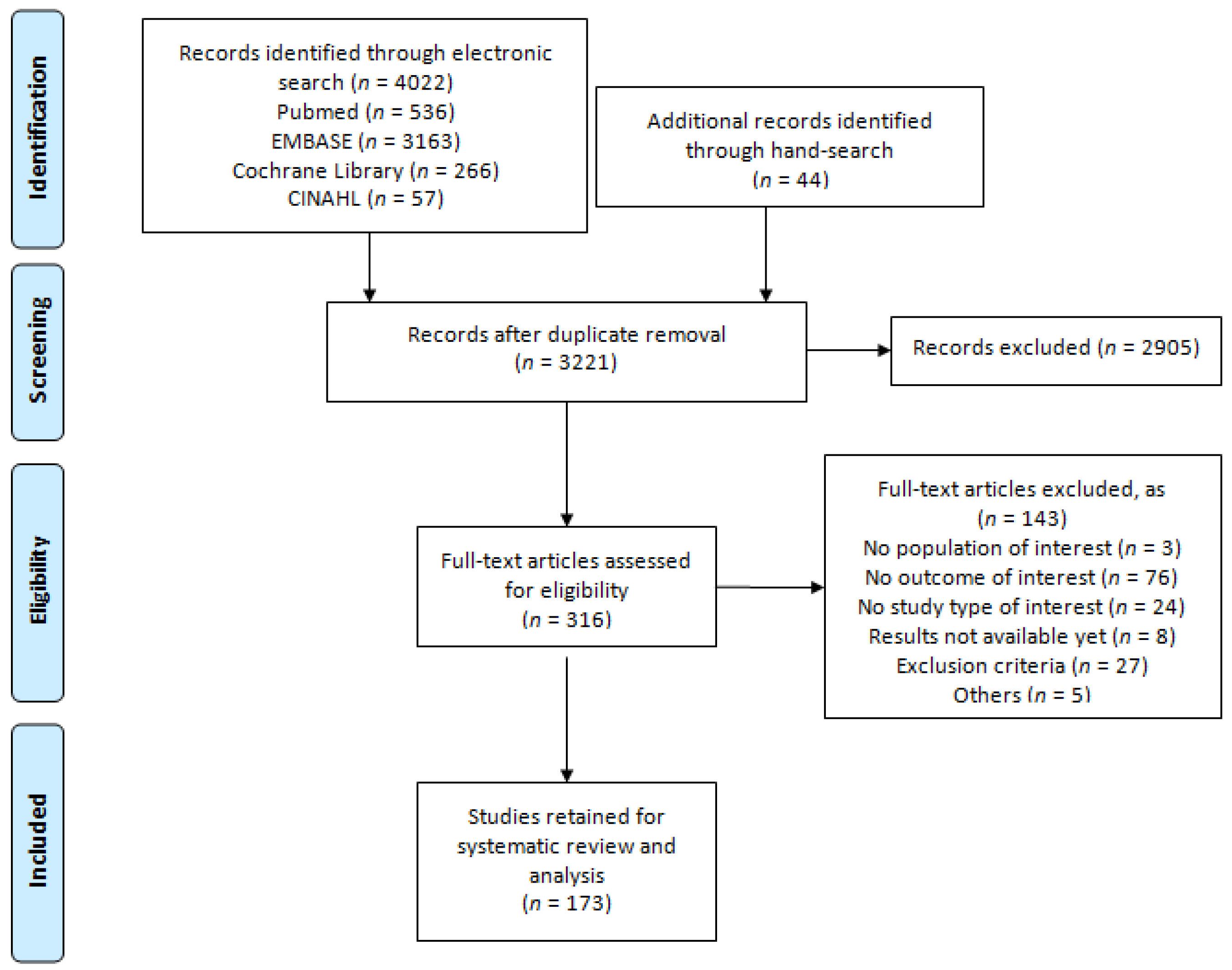

2.1. Literature Search and Study Selection

2.2. Selection Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

2.4. Data Synthesis and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Dose Intensification Requirements

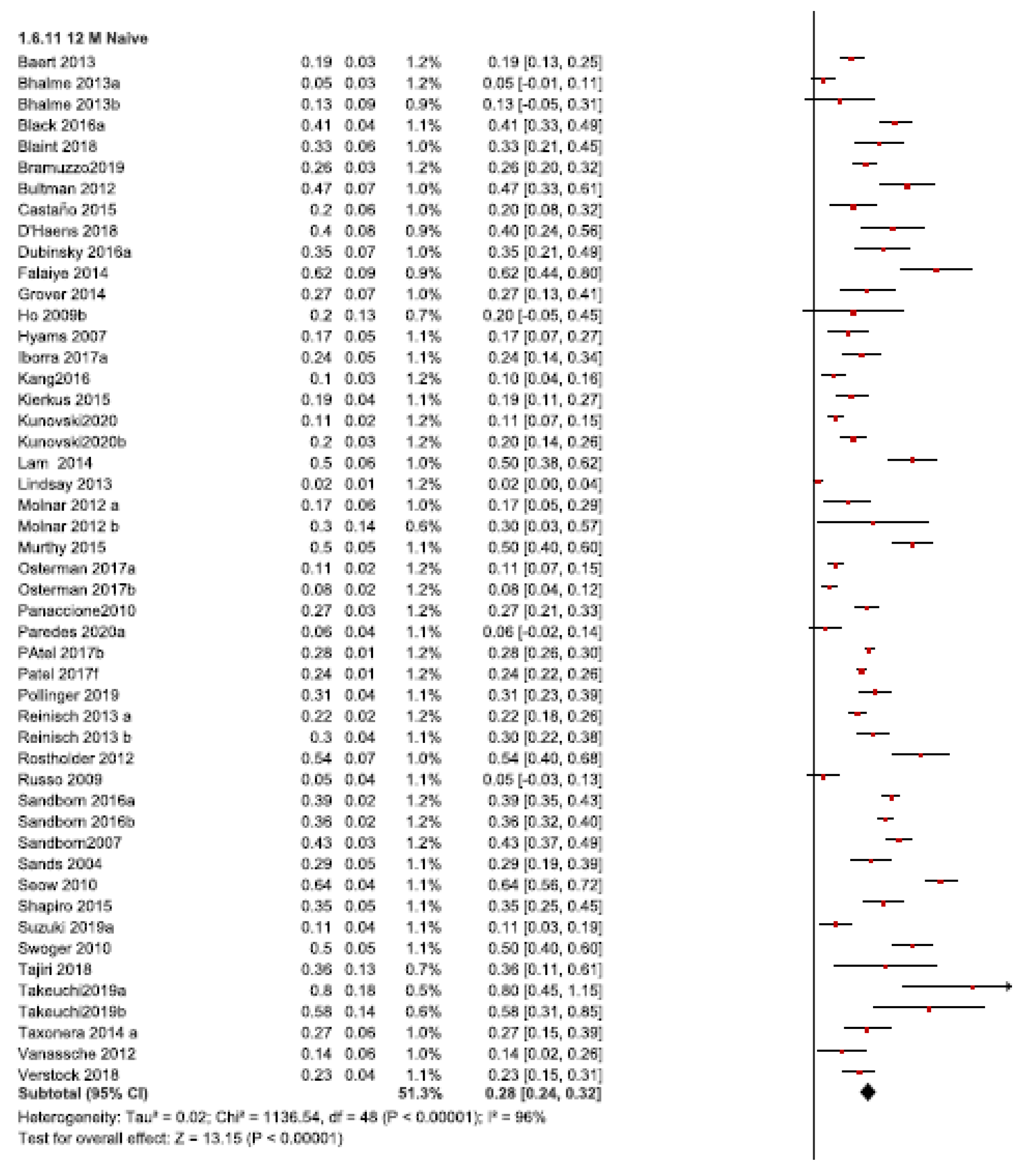

3.1.1. Twelve-Month Follow-Up

3.1.2. Thirty-Six Month Follow-Up

3.1.3. Short-Term Follow up

3.2. Dose Intensification Efficacy

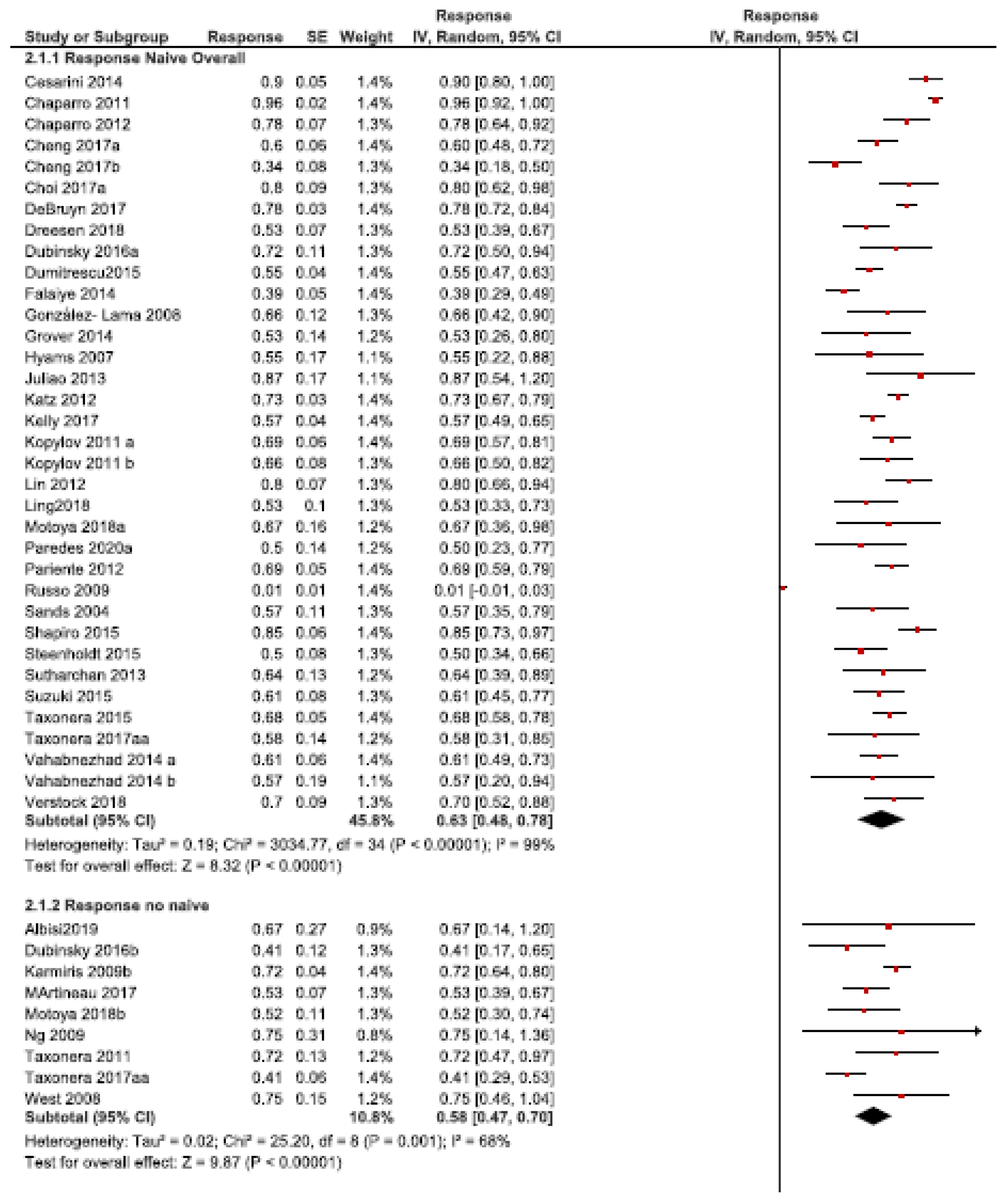

3.2.1. Response Rate

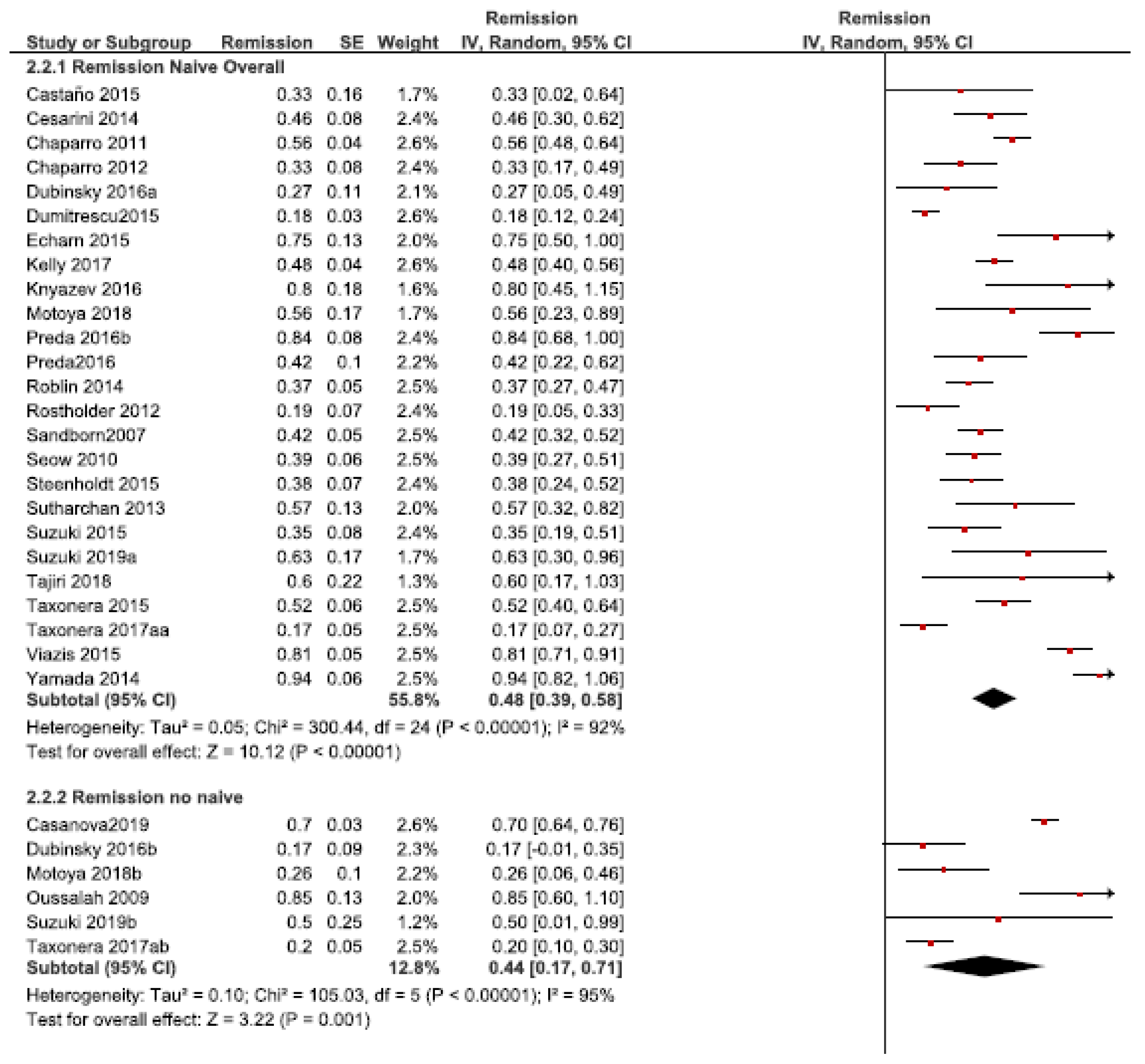

3.2.2. Remission Rate

3.3. Pediatric Population

3.4. Randomized Controlled Trials

3.5. Sensitivity Analyses and Risk of Bias

4. Discussion

4.1. Prior Anti-TNF Exposure

4.2. Time of Follow-Up

4.3. Medical Baseline Condition

4.4. Anti-TNF Agent

4.5. Dose Intensification Efficacy

4.6. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Feldman, M.; Friedman, L.S.; Brandt, L.J. Sleisenger and Fordtran’s Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease E-Book: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, Management, Expert Consult. Premium Edition—Enhanced Online Features; Elsevier Health Sciences: Amsterdam, The Netherland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Van Deventer, S.J. Review article: Targeting TNF alpha as a key cytokine in the inflammatory processes of Crohn’s disease--the mechanisms of action of infliximab. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 1999, 13, 3–8, discussion 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, J.; Bonovas, S.; Doherty, G.; Kucharzik, T.; Gisbert, J.P.; Raine, T.; Adamina, M.; Armuzzi, A.; Bachmann, O.; Bager, P.; et al. ECCO guidelines on therapeutics in Crohn’s disease: Medical treatment. J. Crohn Colitis 2020, 14, 4–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbord, M.; Eliakim, R.; Bettenworth, D.; Karmiris, K.; Katsanos, K.; Kopylov, U.; Kucharzik, T.; Molnár, T.; Raine, T.; Sebastian, S.; et al. Third european evidence-based consensus on diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis. Part 2: Current management. J. Crohn Colitis 2017, 11, 769–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feuerstein, J.D.; Isaacs, K.L.; Schneider, Y.; Siddique, S.M.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Singh, S. AGA clinical practice guidelines on the management of moderate to severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 2020, 158, 1450–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terdiman, J.P.; Gruss, C.B.; Heidelbaugh, J.J.; Sultan, S.; Falck-Ytter, Y.T. American gastroenterological association institute guideline on the use of thiopurines, methotrexate, and anti-TNF-α biologic drugs for the induction and maintenance of remission in inflammatory Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 2013, 145, 1459–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. (Eds.) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Begg, C.B.; Mazumdar, M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 1994, 50, 1088–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Haens, G.; Vermeire, S.; Lambrecht, G.; Baert, F.; Bossuyt, P.; Pariente, B.; Buisson, A.; Bouhnik, Y.; Filippi, J.; Vander Woude, J.; et al. Increasing infliximab dose based on symptoms, biomarkers, and serum drug concentrations does not increase clinical, endoscopic, and corticosteroid-free remission in patients with active luminal Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 2018, 154, 1343–1351.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyams, J.; Crandall, W.; Kugathasan, S.; Griffiths, A.; Olson, A.; Johanns, J.; Liu, G.; Travers, S.; Heuschkel, R.; Markowitz, J.; et al. Induction and maintenance infliximab therapy for the treatment of moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease in children. Gastroenterology 2007, 132, 863–873, quiz 1165–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kierkuś, J.; Iwańczak, B.; Wegner, A.; Dadalski, M.; Grzybowska-Chlebowczyk, U.; Łazowska, I.; Maślana, J.; Toporowska-Kowalska, E.; Czaja-Bulsa, G.; Mierzwa, G.; et al. Monotherapy with infliximab versus combination therapy in the maintenance of clinical remission in children with moderate to severe Crohn disease. J. Pediatric Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2015, 60, 580–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandborn, W.J.; Hanauer, S.B.; Rutgeerts, P.; Fedorak, R.N.; Lukas, M.; MacIntosh, D.G.; Panaccione, R.; Wolf, D.; Kent, J.D.; Bittle, B.; et al. Adalimumab for maintenance treatment of Crohn’s disease: Results of the CLASSIC II trial. Gut 2007, 56, 1232–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sands, B.E.; Anderson, F.H.; Bernstein, C.N.; Chey, W.Y.; Feagan, B.G.; Fedorak, R.N.; Kamm, M.A.; Korzenik, J.R.; Lashner, B.A.; Onken, J.E.; et al. Infliximab maintenance therapy for fistulizing Crohn’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 350, 876–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenholdt, C.; Brynskov, J.; Thomsen, O.; Munck, L.K.; Fallingborg, J.; Christensen, L.A.; Pedersen, G.; Kjeldsen, J.; Jacobsen, B.A.; Oxholm, A.S.; et al. Individualized therapy is a long-term cost-effective method compared to dose intensification in Crohn’s disease patients failing infliximab. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2015, 60, 2762–2770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bossuyt, P.; Baert, F.; D’Heygere, F.; Nakad, A.; Reenaers, C.; Fontaine, F.; Franchimont, D.; Dewit, O.; Van Hootegem, P.; Vanden Branden, S.; et al. Early mucosal healing predicts favorable outcomes in patients with moderate to severe ulcerative colitis treated with golimumab: Data from the real-life BE-SMART cohort. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2019, 25, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dignass, A.; Waller, J.; Cappelleri, J.C.; Modesto, I.; Kisser, A.; Dietz, L.; DiBonaventura, M.; Wood, R.; May, M.; Libutzki, B.; et al. Living with ulcerative colitis in Germany: A retrospective analysis of dose escalation, concomitant treatment use and healthcare costs. J. Med. Econ. 2020, 23, 415–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taxonera, C.; Rodríguez, C.; Bertoletti, F.; Menchén, L.; Arribas, J.; Sierra, M.; Arias, L.; Martínez-Montiel, P.; Juan, A.; Iglesias, E.; et al. Clinical outcomes of golimumab as first, second or third anti-TNF agent in patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2017, 23, 1394–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martineau, C.; Flourié, B.; Wils, P.; Vaysse, T.; Altwegg, R.; Buisson, A.; Amiot, A.; Pineton de Chambrun, G.; Abitbol, V.; Fumery, M.; et al. Efficacy and safety of golimumab in Crohn’s disease: A French national retrospective study. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 46, 1077–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merras-Salmio, L.; Kolho, K.L. Golimumab therapy in six patients with severe pediatric onset Crohn disease. J. Pediatric Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2016, 63, 344–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casanova, M.J.; Chaparro, M.; Mínguez, M.; Ricart, E.; Taxonera, C.; García-López, S.; Guardiola, J.; López-San Román, A.; Iglesias, E.; Beltrán, B.; et al. Effectiveness and safety of the sequential use of a second and third anti-TNF agent in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: Results from the eneida registry. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2020, 26, 606–616. [Google Scholar]

- Knyazev, O.V.; Kagramanova, A.V.; Lishchinskaya, A.A.; Samsonova, N.G.; Orlova, N.V.; Rogozina, V.A.; Parfenov, A.I. Efficacy and tolerability of certolizumab pegol in Crohn’s disease in clinical practice. Ter. Arkhiv 2018, 90, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, W.; Pestana, L.; Becker, B.D.; Loftus, E.V.; Hanson, K.A.; Bruining, D.H.; Tremaine, W.J.; Kane, S.V. Effectiveness and safety of certolizumab pegol for Crohn’s disease in a large cohort followed at a tertiary care center. Gastroenterology 2015, 148, S871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, A.C.; Rubin, D.T.; Hanauer, S.B.; Cohen, R.D. Incidence and predictors of clinical response, re-induction dose, and maintenance dose escalation with certolizumab pegol in Crohn’s disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2014, 20, 1722–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afif, W.; Leighton, J.A.; Hanauer, S.B.; Loftus, E.V., Jr.; Faubion, W.A.; Pardi, D.S.; Tremaine, W.J.; Kane, S.V.; Bruining, D.H.; Cohen, R.D.; et al. Open-label study of adalimumab in patients with ulcerative colitis including those with prior loss of response or intolerance to infliximab. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2009, 15, 1302–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvisi, P.; Arrigo, S.; Cucchiara, S.; Lionetti, P.; Miele, E.; Romano, C.; Ravelli, A.; Knafelz, D.; Martelossi, S.; Guariso, G.; et al. Efficacy of adalimumab as second-line therapy in a pediatric cohort of Crohn’s disease patients who failed infliximab therapy: The Italian society of pediatric gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition experience. Biol. Targets Ther. 2019, 13, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armuzzi, A.; Biancone, L.; Daperno, M.; Coli, A.; Annese, V.; Ardizzone, S.; Balestrieri, P.; Bossa, F.; Castiglione, F.; Cicala, M.; et al. Adalimumab in active ulcerative colitis: A “real-life” observational study. Gastroenterology 2012, 142, S351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assa, A.; Hartman, C.; Weiss, B.; Broide, E.; Rosenbach, Y.; Zevit, N.; Bujanover, Y.; Shamir, R. Long-term outcome of tumor necrosis factor alpha antagonist’s treatment in pediatric Crohn’s disease. J. Crohn Colitis 2013, 7, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baert, F.; Vande Casteele, N.; Tops, S.; Noman, M.; Van Assche, G.; Rutgeerts, P.; Gils, A.; Vermeire, S.; Ferrante, M. Prior response to infliximab and early serum drug concentrations predict effects of adalimumab in ulcerative colitis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2014, 40, 1324–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baert, F.; Glorieus, E.; Reenaers, C.; D’Haens, G.; Peeters, H.; Franchimont, D.; Dewit, O.; Caenepeel, P.; Louis, E.; Van Assche, G. Adalimumab dose escalation and dose de-escalation success rate and predictors in a large national cohort of Crohn’s patients. J. Crohn Colitis 2013, 7, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baki, E.; Zwickel, P.; Zawierucha, A.; Ehehalt, R.; Gotthardt, D.; Stremmel, W.; Gauss, A. Real-life outcome of anti-tumor necrosis factor α in the ambulatory treatment of ulcerative colitis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 3282–3290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bálint, A.; Rutka, M.; Kolar, M.; Bortlik, M.; Duricova, D.; Hruba, V.; Lukas, M.; Mitrova, K.; Malickova, K.; Lukas, M.; et al. Infliximab biosimilar CT-P13 therapy is effective in maintaining endoscopic remission in ulcerative colitis—Results from multicenter observational cohort. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2018, 18, 1181–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bálint, A.; Farkas, K.; Palatka, K.; Lakner, L.; Miheller, P.; Rácz, I.; Hegede, G.; Vincze, Á.; Horváth, G.; Szabó, A.; et al. Efficacy and safety of adalimumab in ulcerative colitis refractory to conventional therapy in routine clinical practice. J. Crohn Colitis 2016, 10, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhalme, M.; Sharma, A.; Keld, R.; Willert, R.; Campbell, S. Does weight-adjusted anti-tumour necrosis factor treatment favour obese patients with Crohn’s disease? Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013, 25, 543–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, C.M.; Yu, E.; McCann, E.; Kachroo, S. Dose escalation and healthcare resource use among ulcerative colitis patients treated with adalimumab in English hospitals: An analysis of real-world data. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0149692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bor, R.; Farkas, K.; Fábián, A.; Bálint, A.; Milassin, Á.; Rutka, M.; Matuz, M.; Nagy, F.; Szepes, Z.; Molnár, T. Clinical role, optimal timing and frequency of serum infliximab and anti-infliximab antibody level measurements in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0172916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bortlik, M.; Duricova, D.; Malickova, K.; Machkova, N.; Bouzkova, E.; Hrdlicka, L.; Komarek, A.; Lukas, M. Infliximab trough levels may predict sustained response to infliximab in patients with Crohn’s disease. J. Crohn Colitis 2013, 7, 736–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bossuyt, P.; Baert, F.; D’Heygere, F.; Nakad, A.; Louis, E.; Fontaine, F.; Franchimont, D.; Dewit, O.; Van Hootegem, P.; Vanden Branden, S.; et al. Early mucosal healing in patients with moderate to severe ulcerative colitis treated with golimumab predicts favorable outcomes: Data from the real-life be-smart cohort. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2017, 5, A23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouguen, G.; Laharie, D.; Nancey, S.; Hebuterne, X.; Flourie, B.; Filippi, J.; Roblin, X.; Trang, C.; Bourreille, A.; Babouri, A.; et al. Efficacy and safety of adalimumab 80 mg weekly in luminal Crohn’s disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2015, 21, 1047–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bramuzzo, M.; Arrigo, S.; Romano, C.; Filardi, M.C.; Lionetti, P.; Agrusti, A.; Dipasquale, V.; Paci, M.; Zuin, G.; Aloi, M.; et al. Efficacy and safety of infliximab in very early onset inflammatory bowel disease: A national comparative retrospective study. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2019, 7, 759–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandes, A.; Groth, A.; Gottschalk, F.; Wilke, T.; Ratsch, B.A.; Orzechowski, H.D.; Fuchs, A.; Deiters, B.; Bokemeyer, B. Real-world biologic treatment and associated cost in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Z. Fur Gastroenterol. 2019, 57, 843–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bultman, E.; de Haar, C.; van Liere-Baron, A.; Verhoog, H.; West, R.L.; Kuipers, E.J.; Zelinkova, Z.; van der Woude, C.J. Predictors of dose escalation of adalimumab in a prospective cohort of Crohn’s disease patients. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2012, 35, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cameron, F.L.; Wilson, M.L.; Basheer, N.; Jamison, A.; McGrogan, P.; Bisset, W.M.; Gillett, P.M.; Russell, R.K.; Wilson, D.C. Anti-TNF therapy for paediatric IBD: The scottish national experience. Arch. Dis. Child. 2015, 100, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casellas, F.; Herrera De Guise, C.; Robles, V.; Torrejón, A.; Navarro, E.; Borruel, N. Long-term normalization of quality of life in patients with Crohn’s disease following maintenance therapy with adalimumab. Enferm. Inflamatoria Intest. 2015, 14, 5–10. [Google Scholar]

- Castaño-Milla, C.; Chaparro, M.; Saro, C.; Barreiro-de Acosta, M.; García-Albert, A.M.; Bujanda, L.; Martín-Arranz, M.D.; Carpio, D.; Muñoz, F.; Manceñido, N.; et al. Effectiveness of adalimumab in perianal fistulas in crohn’s disease patients naive to anti-TNF therapy. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2015, 49, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caviglia, R.; Ribolsi, M.; Rizzi, M.; Emerenziani, S.; Annunziata, M.; Cicala, M. Maintenance of remission with infliximab in inflammatory bowel disease: Efficacy and safety long-term follow-up. World J. Gastroenterol. 2007, 13, 5238–5244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cesarini, M.; Katsanos, K.; Papamichael, K.; Ellul, P.; Lakatos, P.L.; Caprioli, F.; Kopylov, U.; Tsianos, E.; Mantzaris, G.J.; Ben-Horin, S.; et al. Dose optimization is effective in ulcerative colitis patients losing response to infliximab: A collaborative multicentre retrospective study. Dig. Liver Dis. Off. J. Ital. Soc. Gastroenterol. Ital. Assoc. Study Liver 2014, 46, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaparro, M.; Panes, J.; García, V.; Mañosa, M.; Esteve, M.; Merino, O.; Andreu, M.; Gutierrez, A.; Gomollón, F.; Cabriada, J.L.; et al. Long-term durability of infliximab treatment in Crohn’s disease and efficacy of dose “escalation” in patients losing response. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2011, 45, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaparro, M.; Martínez-Montiel, P.; Van Domselaar, M.; Bermejo, F.; Pérez-Calle, J.L.; Casis, B.; Román, A.L.; Algaba, A.; Maté, J.; Gisbert, J.P. Intensification of infliximab therapy in Crohn’s disease: Efficacy and safety. J. Crohn Colitis 2012, 6, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Hamilton, Z.; Smyth, M.; Barker, C.; Israel, D.; Jacobson, K. Concomitant therapy with immunomodulator enhances infliximab durability in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2017, 23, 1762–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, G.K.; Collins, S.D.; Greer, D.P.; Warren, L.; Dowson, G.; Clark, T.; Hamlin, P.J.; Ford, A.C. Costs of adalimumab versus infliximab as first-line biological therapy for luminal Crohn’s disease. J. Crohn Colitis 2014, 8, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.Y.; Kang, B.; Lee, J.H.; Choe, Y.H. Clinical use of measuring trough levels and antibodies against infliximab in patients with pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Gut Liver 2017, 11, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, P.C.; Guan, J.; Walters, T.D.; Frost, K.; Assa, A.; Muise, A.M.; Griffiths, A.M. Infliximab maintains durable response and facilitates catch-up growth in luminal pediatric Crohn’s disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2014, 20, 1177–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark-Snustad, K.D.; Singla, A.; Lee, S.D. Efficacy of infliximab in Crohn’s disease patients with prior primary-nonresponse to tumor necrosis factor antagonists. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2019, 64, 1952–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, R.D.; Lewis, J.R.; Turner, H.; Harrell, L.E.; Hanauer, S.B.; Rubin, D.T. Predictors of adalimumab dose escalation in patients with Crohn’s disease at a tertiary referral center. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2012, 18, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordero Ruiz, P.; Castro Márquez, C.; Méndez Rufián, V.; Castro Laria, L.; Caunedo Álvarez, A.; Romero Vázquez, J.; Herrerías Gutiérrez, J.M. Efficacy of adalimumab in patients with Crohn’s disease and failure to infliximab therapy: A clinical series. Rev. Esp. Enferm. Dig. Organo Of. Soc. Esp. Patol. Dig. 2011, 103, 294–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Ridder, L.; Rings, E.H.; Damen, G.M.; Kneepkens, C.M.; Schweizer, J.J.; Kokke, F.T.; Benninga, M.A.; Norbruis, O.F.; Hoekstra, J.H.; Gijsbers, C.F.; et al. Infliximab dependency in pediatric Crohn’s disease: Long-term follow-up of an unselected cohort. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2008, 14, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeBruyn, J.C.; Jacobson, K.; El-Matary, W.; Carroll, M.; Wine, E.; Wrobel, I.; Van Woudenberg, M.; Huynh, H.Q. Long-term outcomes of infliximab use for pediatric Crohn disease: A canadian multicenter clinical practice experience. J. Pediatric Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2018, 66, 268–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dreesen, E.; Van Stappen, T.; Ballet, V.; Peeters, M.; Compernolle, G.; Tops, S.; Van Steen, K.; Van Assche, G.; Ferrante, M.; Vermeire, S.; et al. Anti-infliximab antibody concentrations can guide treatment intensification in patients with Crohn’s disease who lose clinical response. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 47, 346–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubinsky, M.C.; Rosh, J.; Faubion, W.A., Jr.; Kierkus, J.; Ruemmele, F.; Hyams, J.S.; Eichner, S.; Li, Y.; Huang, B.; Mostafa, N.M.; et al. Efficacy and safety of escalation of adalimumab therapy to weekly dosing in pediatric patients with Crohn’s disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2016, 22, 886–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumitrescu, G.; Amiot, A.; Seksik, P.; Baudry, C.; Stefanescu, C.; Gagniere, C.; Allez, M.; Cosnes, J.; Bouhnik, Y. The outcome of infliximab dose doubling in 157 patients with ulcerative colitis after loss of response to infliximab. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015, 42, 1192–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Dupont-Lucas, C.; Sternszus, R.; Ezri, J.; Leibovitch, S.; Gervais, F.; Amre, D.; Deslandres, C. Identifying patients at high risk of loss of response to infliximab maintenance therapy in paediatric Crohn’s disease. J. Crohn Colitis 2016, 10, 795–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duveau, N.; Nachury, M.; Gerard, R.; Branche, J.; Maunoury, V.; Boualit, M.; Wils, P.; Desreumaux, P.; Pariente, B. Adalimumab dose escalation is effective and well tolerated in Crohn’s disease patients with secondary loss of response to adalimumab. Dig. Liver Dis. Off. J. Ital. Soc. Gastroenterol. Ital. Assoc. Study Liver 2017, 49, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Echarri, A.; Ollero, V.; Barreiro-de Acosta, M.; Fernández-Villaverde, A.; Hernández, V.; Lorenzo, A.; Pereira, S.; Carpio, D.; Castro, J. Clinical, biological, and endoscopic responses to adalimumab in antitumor necrosis factor-naive Crohn’s disease: Predictors of efficacy in clinical practice. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 27, 430–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falaiye, T.O.; Mitchell, K.R.; Lu, Z.; Saville, B.R.; Horst, S.N.; Moulton, D.E.; Schwartz, D.A.; Wilson, K.T.; Rosen, M.J. Outcomes following infliximab therapy for pediatric patients hospitalized with refractory colitis-predominant IBD. J. Pediatric Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2014, 58, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, S.R.; Bernardo, S.; Simões, C.; Gonçalves, A.R.; Valente, A.; Baldaia, C.; Moura Santos, P.; Correia, L.A.; Tato Marinho, R. Proactive infliximab drug monitoring is superior to conventional management in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2020, 26, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Salazar, L.; Barrio, J.; Muñoz, F.; Muñoz, C.; Pajares, R.; Rivero, M.; Prieto, V.; Legido, J.; Bouhmidi, A.; Herranz, M.; et al. Frequency, predictors, and consequences of maintenance infliximab therapy intensification in ulcerative colitis. Rev. Esp. Enferm. Dig. Organo Of. Soc. Esp. Patol. Dig. 2015, 107, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fiorino, G.; Manetti, N.; Variola, A.; Bossa, F.; Rizzuto, G.; Armuzzi, A.; Massari, A.; Ghione, S.; Cantoro, L.; Lorenzon, G.; et al. The prosit-bio cohort of the IG-IBD: A prospective observational study of patients with inflammatory bowel disease treated with infliximab biosimilars. Gastroenterology 2016, 150, S92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortea-Ormaechea, J.I.; González-Lama, Y.; Casis, B.; Chaparro, M.; López Serrano, P.; Van Domselaar, M.; Bermejo, F.; Pajares, R.; Ponferrada, A.; Vera, M.I.; et al. Adalimumab is effective in long-term real life clinical practice in both luminal and perianal Crohn’s disease. The Madrid experience. Gastroenterol. Y Hepatol. 2011, 34, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frederiksen, M.T.; Ainsworth, M.A.; Brynskov, J.; Thomsen, O.O.; Bendtzen, K.; Steenholdt, C. Antibodies against infliximab are associated with de novo development of antibodies to adalimumab and therapeutic failure in infliximab-to-adalimumab switchers with IBD. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2014, 20, 1714–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Bosch, O.; Gisbert, J.P.; Cañas-Ventura, A.; Merino, O.; Cabriada, J.L.; García-Sánchez, V.; Gutiérrez, A.; Nos, P.; Peñalva, M.; Hinojosa, J.; et al. Observational study on the efficacy of adalimumab for the treatment of ulcerative colitis and predictors of outcome. J. Crohn Colitis 2013, 7, 717–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaly, S.; Costello, S.; Beswick, L.; Pudipeddi, A.; Agarwal, A.; Sechi, A.; Antoniades, S.; Headon, B.; Connor, S.; Lawrance, I.C.; et al. Dose tailoring of anti-tumour necrosis factor-alpha therapy delivers useful clinical efficacy in Crohn disease patients experiencing loss of response. Intern. Med. J. 2015, 45, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gofin, Y.; Matar, M.; Shamir, R.; Assa, A. Therapeutic drug monitoring increases drug retention of anti-Tumor necrosis factor alpha agents in pediatric patients with Crohn’s disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2020, 26, 1276–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonczi, L.; Kurti, Z.; Rutka, M.; Vegh, Z.; Farkas, K.; Lovasz, B.D.; Golovics, P.A.; Gecse, K.B.; Szalay, B.; Molnar, T.; et al. Drug persistence and need for dose intensification to adalimumab therapy; the importance of therapeutic drug monitoring in inflammatory bowel diseases. BMC Gastroenterol. 2017, 17, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzaga, J.E.; Ananthakrishnan, A.N.; Issa, M.; Beaulieu, D.B.; Skaros, S.; Zadvornova, Y.; Johnson, K.; Otterson, M.F.; Binion, D.G. Durability of infliximab in Crohn’s disease: A single-center experience. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2009, 15, 1837–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Lama, Y.; López-San Román, A.; Marín-Jiménez, I.; Casis, B.; Vera, I.; Bermejo, F.; Pérez-Calle, J.L.; Taxonera, C.; Martínez-Silva, F.; Menchén, L.; et al. Open-label infliximab therapy in Crohn’s disease: A long-term multicenter study of efficacy, safety and predictors of response. Gastroenterol. Y Hepatol. 2008, 31, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Grover, Z.; Biron, R.; Carman, N.; Lewindon, P. Predictors of response to Infliximab in children with luminal Crohn’s disease. J. Crohn Colitis 2014, 8, 739–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerbau, L.; Gerard, R.; Duveau, N.; Staumont-Sallé, D.; Branche, J.; Maunoury, V.; Cattan, S.; Wils, P.; Boualit, M.; Libier, L.; et al. Patients with Crohn’s disease with high body mass index present more frequent and rapid loss of response to infliximab. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2017, 23, 1853–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidi, L.; Pugliese, D.; Tonucci, T.P.; Berrino, A.; Tolusso, B.; Basile, M.; Cantoro, L.; Balestrieri, P.; Civitelli, F.; Bertani, L.; et al. Therapeutic drug monitoring is more cost-effective than a clinically based approach in the management of loss of response to infliximab in inflammatory bowel disease: An observational multicentre study. J. Crohn Colitis 2018, 12, 1079–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, G.T.; Smith, L.; Aitken, S.; Lee, H.M.; Ting, T.; Fennell, J.; Lees, C.W.; Palmer, K.R.; Penman, I.D.; Shand, A.G.; et al. The use of adalimumab in the management of refractory Crohn’s disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2008, 27, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, G.T.; Mowat, A.; Potts, L.; Cahill, A.; Mowat, C.; Lees, C.W.; Hare, N.C.; Wilson, J.A.; Boulton-Jones, R.; Priest, M.; et al. Efficacy and complications of adalimumab treatment for medically-refractory Crohn’s disease: Analysis of nationwide experience in Scotland (2004–2008). Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009, 29, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussey, M.; Mc Garrigle, R.; Kennedy, U.; Holleran, G.; Kevans, D.; Ryan, B.; Breslin, N.; Mahmud, N.; McNamara, D. Long-term assessment of clinical response to adalimumab therapy in refractory ulcerative colitis. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 28, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyams, J.S.; Lerer, T.; Griffiths, A.; Pfefferkorn, M.; Stephens, M.; Evans, J.; Otley, A.; Carvalho, R.; Mack, D.; Bousvaros, A.; et al. Outcome following infliximab therapy in children with ulcerative colitis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 105, 1430–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iborra, M.; Pérez-Gisbert, J.; Bosca-Watts, M.M.; López-García, A.; García-Sánchez, V.; López-Sanromán, A.; Hinojosa, E.; Márquez, L.; García-López, S.; Chaparro, M.; et al. Effectiveness of adalimumab for the treatment of ulcerative colitis in clinical practice: Comparison between anti-tumour necrosis factor-naïve and non-naïve patients. J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 52, 788–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inokuchi, T.; Takahashi, S.; Hiraoka, S.; Toyokawa, T.; Takagi, S.; Takemoto, K.; Miyaike, J.; Fujimoto, T.; Higashi, R.; Morito, Y.; et al. Long-term outcomes of patients with Crohn’s disease who received infliximab or adalimumab as the first-line biologics. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 34, 1329–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juillerat, P.; Sokol, H.; Yajnik, V.; Froehlich, F.; Beaugerie, L.; Cosnes, J.; Burnand, B.; Macpherson, A.J.; Korzenik, J.R.; Lucci, M. Factors associated with durable response to infliximab 5 years and beyond: A multi center international cohort. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2013, 1, A33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliao, F.; Marquez, J.; Aristizabal, N.; Carlos, Y.; Julio, Z.; Gisbert, J.P. Clinical efficacy of infliximab in moderate to severe ulcerative. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2012, 18, S18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, B.; Choi, S.Y.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, K.; Lee, Y.M.; Choe, Y.H. Mucosal healing in paediatric patients with moderate-to-severe luminal Crohn’s disease under combined immunosuppression: Escalation versus early treatment. J. Crohn Colitis 2016, 10, 1279–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmiris, K.; Paintaud, G.; Noman, M.; Magdelaine-Beuzelin, C.; Ferrante, M.; Degenne, D.; Claes, K.; Coopman, T.; Van Schuerbeek, N.; Van Assche, G.; et al. Influence of trough serum levels and immunogenicity on long-term outcome of adalimumab therapy in Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 2009, 137, 1628–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, L.; Gisbert, J.P.; Manoogian, B.; Lin, K.; Steenholdt, C.; Mantzaris, G.J.; Atreja, A.; Ron, Y.; Swaminath, A.; Shah, S.; et al. Doubling the infliximab dose versus halving the infusion intervals in Crohn’s disease patients with loss of response. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2012, 18, 2026–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, O.B.; Donnell, S.O.; Stempak, J.M.; Steinhart, A.H.; Silverberg, M.S. Therapeutic drug monitoring to guide infliximab dose adjustment is associated with better endoscopic outcomes than clinical decision making alone in active inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2017, 23, 1202–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, L.S.; Szamosi, T.; Molnar, T.; Miheller, P.; Lakatos, L.; Vincze, A.; Palatka, K.; Barta, Z.; Gasztonyi, B.; Salamon, A.; et al. Early clinical remission and normalisation of CRP are the strongest predictors of efficacy, mucosal healing and dose escalation during the first year of adalimumab therapy in Crohn’s disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011, 34, 911–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knyazev, O.V.; Parfenov, A.I.; Kagramanova, A.V.; Ruchkina, I.N.; Shcherbakov, P.L.; Shakhpazyan, N.K.; Noskova, K.K.; Ivkina, T.I.; Khomeriki, S.G. Long-term infliximab therapy for ulcerative colitis in real clinical practice. Ter. Arkhiv 2016, 88, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knyazev, O.V.; Kagramanova, A.V.; Ruchkina, I.N.; Fadeeva, N.A.; Lishchinskaya, A.A.; Boldyreva, O.N.; Zhulina, E.Y.; Shcherbakov, P.L.; Orlova, N.V.; Kirova, M.V.; et al. Efficacy of adalimumab for Crohn’s disease in real clinical practice. Ter. Arkhiv 2017, 89, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopylov, U.; Mantzaris, G.J.; Katsanos, K.H.; Reenaers, C.; Ellul, P.; Rahier, J.F.; Israeli, E.; Lakatos, P.L.; Fiorino, G.; Cesarini, M.; et al. The efficacy of shortening the dosing interval to once every six weeks in Crohn’s patients losing response to maintenance dose of infliximab. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011, 33, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunovszki, P.; Judit Szántó, K.; Gimesi-Országh, J.; Takács, P.; Borsi, A.; Bálint, A.; Farkas, K.; Milassin, Á.; Lakatos, P.L.; Szamosi, T.; et al. Epidemiological data and utilization patterns of anti-TNF alpha therapy in the hungarian ulcerative colitis population between 2012–2016. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2020, 20, 443–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, M.C.; Lee, T.; Atkinson, K.; Bressler, B. Time of infliximab therapy initiation and dose escalation in Crohn’s disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 214–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lees, C.W.; Ali, A.I.; Thompson, A.I.; Ho, G.T.; Forsythe, R.O.; Marquez, L.; Cochrane, C.J.; Aitken, S.; Fennell, J.; Rogers, P.; et al. The safety profile of anti-tumour necrosis factor therapy in inflammatory bowel disease in clinical practice: Analysis of 620 patient-years follow-up. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009, 29, 286–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, K.K.; Velayos, F.; Fisher, E.; Terdiman, J.P. Durability of infliximab dose intensification in Crohn’s disease. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2012, 57, 1013–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindsay, J.O.; Chipperfield, R.; Giles, A.; Wheeler, C.; Orchard, T. A UK retrospective observational study of clinical outcomes and healthcare resource utilisation of infliximab treatment in Crohn’s disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013, 38, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindsay, J.O.; Armuzzi, A.; Gisbert, J.P.; Bokemeyer, B.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Nguyen, G.C.; Smyth, M.; Patel, H. Indicators of suboptimal tumor necrosis factor antagonist therapy in inflammatory bowel disease. Dig. Liver Dis. Off. J. Ital. Soc. Gastroenterol. Ital. Assoc. Study Liver 2017, 49, 1086–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, J.; Buurman, D.; Ravikumara, M.; Mews, C.; Thacker, K.; Grover, Z. Accelerated step-up infliximab use is associated with sustained primary response in pediatric Crohn’s disease. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2018, 63, 1003–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llaó, J.; Naves, J.E.; Ruiz-Cerulla, A.; Romero, C.; Mañosa, M.; Lobatón, T.; Cabré, E.; Guardiola, J.; Garcia-Planella, E.; Domènech, E. Tratamiento de mantenimiento con azatioprina o infliximab en pacientes con colitis ulcerosa corticorrefractarios respondedores a las 3 dosis de inducción de infliximab. Enferm. Inflamatoria Intest. 2017, 16, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lofberg, R.; Louis, E.; Reinisch, W.; Robinson, A.; Kron, M.; Camez, A.; Pollack, P. Clinical outcomes in patients with moderate versus severe Crohn’s disease at baseline: Analysis from CARE. J. Crohn Colitis 2012, 6, S94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- López Palacios, N.; Mendoza, J.L.; Taxonera, C.; Lana, R.; Fuentes Ferrer, M.; Díaz-Rubio, M. Adalimumab induction and maintenance therapy for Crohn’s disease. An open-label study. Rev. Esp. Enferm. Dig. Organo Of. Soc. Esp. Patol. Dig. 2008, 100, 676–681. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, C.; Huang, V.; Fedorak, D.K.; Kroeker, K.I.; Dieleman, L.A.; Halloran, B.P.; Fedorak, R.N. Outpatient ulcerative colitis primary anti-TNF responders receiving adalimumab or infliximab maintenance therapy have similar rates of secondary loss of response. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2015, 49, 675–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, C.; Huang, V.; Fedorak, D.K.; Kroeker, K.I.; Dieleman, L.A.; Fedorak, R.N. Crohn’s disease outpatients treated with adalimumab have an earlier loss of response and requirement for dose intensification compared to infliximab. Gastroenterology 2014, 146, S457–S458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Beilman, C.L.; Huang, V.W.; Fedorak, D.K.; Kroeker, K.I.; Dieleman, L.A.; Halloran, B.P.; Fedorak, R.N. Anti-TNF therapy within 2 years of Crohn’s disease diagnosis improves patient outcomes: A retrospective cohort study. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2016, 22, 870–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, C.; Huang, V.; Fedorak, D.K.; Kroeker, K.I.; Dieleman, L.A.; Halloran, B.P.; Fedorak, R.N. Adalimumab dose escalation is effective for managing secondary loss of response in Crohn’s disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2014, 40, 1044–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magro, F.; Rodrigues-Pinto, E.; Lopes, S.; Macedo, G. Earlier need of infliximab intensification in ulcerative colitis than in Crohn’s disease. J. Crohn Colitis 2014, 8, 1331–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnár, T.; Farkas, K.; Nyári, T.; Szepes, Z.; Nagy, F.; Wittmann, T. Frequency and predictors of loss of response to infliximab or adalimumab in Crohn’s disease after one-year treatment period-a single center experience. J. Gastrointest. Liver Dis. JGLD 2012, 21, 265–269. [Google Scholar]

- Motoya, S.; Watanabe, M.; Wallace, K.; Lazar, A.; Nishimura, Y.; Ozawa, M.; Thakkar, R.; Robinson, A.M.; Singh, R.S.P.; Mostafa, N.M.; et al. Efficacy and safety of dose escalation to adalimumab 80 mg every other week in Japanese patients with Crohn’s disease who lost response to maintenance therapy. Inflamm. Intest. Dis. 2018, 2, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroi, R.; Shiga, H.; Endo, K.; Yamamoto, K.; Kuroha, M.; Kanazawa, Y.; Kakuta, Y.; Kinouchi, Y.; Masamune, A. Long-term prognosis of Japanese patients with Crohn’s disease treated by switching anti-tumor necrosis factor-α antibodies. Inflamm. Intest. Dis. 2020, 5, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, S.K.; Greenberg, G.R.; Croitoru, K.; Nguyen, G.C.; Silverberg, M.S.; Steinhart, A.H. Extent of early clinical response to infliximab predicts long-term treatment success in active ulcerative colitis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2015, 21, 2090–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narula, N.; Kainz, S.; Petritsch, W.; Haas, T.; Feichtenschlager, T.; Novacek, G.; Eser, A.; Vogelsang, H.; Reinisch, W.; Papay, P. The efficacy and safety of either infliximab or adalimumab in 362 patients with anti-TNF-α naïve Crohn’s disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2016, 44, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nedelkopoulou, N.; Vadamalayan, B.; Vergani, D.; Mieli-Vergani, G. Anti-TNFα treatment in children and adolescents with combined inflammatory bowel disease and autoimmune liver disease. J. Pediatric Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2018, 66, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.C.; Plamondon, S.; Gupta, A.; Burling, D.; Swatton, A.; Vaizey, C.J.; Kamm, M.A. Prospective evaluation of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy guided by magnetic resonance imaging for Crohn’s perineal fistulas. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2009, 104, 2973–2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nichita, C.; Stelle, M.; Vavricka, S.R.; El-Wafa, A.A.; De Saussure, P.; Straumann, A.; Rogler, G.; Michetti, P.F. Clinical experience with adalimumab in a multicenter swiss cohort of patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 2009, 136, A681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuti, F.; Viola, F.; Civitelli, F.; Alessandri, C.; Aloi, M.; Dilillo, A.; Del Giudice, E.; Cucchiara, S. Biological therapy in a pediatric Crohn disease population at a referral center. J. Pediatric Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2014, 58, 582–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Donnell, S.; Stempak, J.M.; Steinhart, A.H.; Silverberg, M.S. Higher rates of dose optimisation for infliximab responders in ulcerative colitis than in Crohn’s disease. J. Crohn Colitis 2015, 9, 830–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivares, D.; Alba, C.; Pérez, I.; Roales, V.; Rey, E.; Taxonera, C. Differences in the need for adalimumab dose optimization between Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Rev. Esp. Enferm. Dig. Organo Of. Soc. Esp. Patol. Dig. 2019, 111, 846–851. [Google Scholar]

- Orlando, A.; Renna, S.; Mocciaro, F.; Cappello, M.; Di Mitri, R.; Randazzo, C.; Cottone, M. Adalimumab in steroid-dependent Crohn’s disease patients: Prognostic factors for clinical benefit. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2012, 18, 826–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterman, M.T.; Haynes, K.; Delzell, E.; Zhang, J.; Bewtra, M.; Brensinger, C.M.; Chen, L.; Xie, F.; Curtis, J.R.; Lewis, J.D. Effectiveness and safety of immunomodulators with anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in Crohn’s disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Off. Clin. Pract. J. Am. Gastroenterol. Assoc. 2015, 13, 1293–1301.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oussalah, A.; Babouri, A.; Chevaux, J.B.; Stancu, L.; Trouilloud, I.; Bensenane, M.; Boucekkine, T.; Bigard, M.A.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L. Adalimumab for Crohn’s disease with intolerance or lost response to infliximab: A 3-year single-centre experience. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009, 29, 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oussalah, A.; Evesque, L.; Laharie, D.; Roblin, X.; Boschetti, G.; Nancey, S.; Filippi, J.; Flourié, B.; Hebuterne, X.; Bigard, M.A.; et al. A multicenter experience with infliximab for ulcerative colitis: Outcomes and predictors of response, optimization, colectomy, and hospitalization. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 105, 2617–2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panaccione, R.; Colombel, J.F.; Sandborn, W.J.; Rutgeerts, P.; D’Haens, G.R.; Robinson, A.M.; Chao, J.; Mulani, P.M.; Pollack, P.F. Adalimumab sustains clinical remission and overall clinical benefit after 2 years of therapy for Crohn’s disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2010, 31, 1296–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes Méndez, J.E.; Alosilla Sandoval, P.A.; Vargas Marcacuzco, H.T.; Mestanza Rivas Plata, A.L.; Gonzá Les Yovera, J.G. Loss of response to anti-TNF therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: Experience in a reference hospital in Lima-Peru. Rev. Gastroenterol. Peru Organo Of. Soc. Gastroenterol. Peru 2020, 40, 22–28. [Google Scholar]

- Pariente, B.; Pineton de Chambrun, G.; Krzysiek, R.; Desroches, M.; Louis, G.; De Cassan, C.; Baudry, C.; Gornet, J.M.; Desreumaux, P.; Emilie, D.; et al. Trough levels and antibodies to infliximab may not predict response to intensification of infliximab therapy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2012, 18, 1199–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H.; Hwang, S.W.; Kwak, M.S.; Kim, W.S.; Lee, J.M.; Lee, H.S.; Yang, D.H.; Kim, K.J.; Ye, B.D.; Byeon, J.S.; et al. Long-term outcomes of infliximab treatment in 582 Korean patients with Crohn’s disease: A hospital-based cohort study. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2016, 61, 2060–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, H.; Lissoos, T.; Rubin, D.T. Indicators of suboptimal biologic therapy over time in patients with ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease in the United States. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0175099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Del Tedesco, E.; Marotte, H.; Rinaudo-Gaujous, M.; Moreau, A.; Phelip, J.M.; Genin, C.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Roblin, X. Therapeutic drug monitoring of infliximab and mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel disease: A prospective study. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2013, 19, 2568–2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, C.P.; Eshuis, E.J.; Toxopeüs, F.M.; Hellemons, M.E.; Jansen, J.M.; D’Haens, G.R.; Fockens, P.; Stokkers, P.C.; Tuynman, H.A.; van Bodegraven, A.A.; et al. Adalimumab for Crohn’s disease: Long-term sustained benefit in a population-based cohort of 438 patients. J. Crohn Colitis 2014, 8, 866–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Laclotte, C.; Bigard, M.A. Adalimumab maintenance therapy for Crohn’s disease with intolerance or lost response to infliximab: An open-label study. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2007, 25, 675–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pöllinger, B.; Schmidt, W.; Seiffert, A.; Imhoff, H.; Emmert, M. Costs of dose escalation among ulcerative colitis patients treated with adalimumab in Germany. Eur. J. Health Econ. HEPAC Health Econ. Prev. Care 2019, 20, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preda, C.; Fulger, L.; Gheorghe, L.; Gheorghe, C.; Goldis, A.; Trifan, A.; Tantau, M.; Tantau, A.; Negreanu, L.; Manuc, M.; et al. Adalimumab and Infliximab in Crohn’s disease-real life data from a national retrospective cohort study. Curr. Health Sci. J. 2016, 42, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Qazi, T.; Shah, B.; El-Dib, M.; Farraye, F.A. The Tolerability and efficacy of rapid infliximab infusions in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2016, 61, 589–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regueiro, M.; Siemanowski, B.; Kip, K.E.; Plevy, S. Infliximab dose intensification in Crohn’s disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2007, 13, 1093–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinisch, W.; Sandborn, W.J.; Panaccione, R.; Huang, B.; Pollack, P.F.; Lazar, A.; Thakkar, R.B. 52-week efficacy of adalimumab in patients with moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis who failed corticosteroids and/or immunosuppressants. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2013, 19, 1700–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renna, S.; Orlando, E.; Macaluso, F.S.; Maida, M.; Affronti, M.; Giunta, M.; Sapienza, C.; Rizzuto, G.; Orlando, R.; Dimarco, M.; et al. Letter: A prospective real life comparison of the efficacy of adalimumab vs. golimumab in moderate to severe ulcerative colitis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2016, 44, 310–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renna, S.; Mocciaro, F.; Ventimiglia, M.; Orlando, R.; Macaluso, F.S.; Cappello, M.; Fries, W.; Mendolaro, M.; Privitera, A.C.; Ferracane, C.; et al. A real life comparison of the effectiveness of adalimumab and golimumab in moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis, supported by propensity score analysis. Dig. Liver Dis. Off. J. Ital. Soc. Gastroenterol. Ital. Assoc. Study Liver 2018, 50, 1292–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riis, A.; Martinsen, T.C.; Waldum, H.L.; Fossmark, R. Clinical experience with infliximab and adalimumab in a single-center cohort of patients with Crohn’s disease. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 47, 649–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roblin, X.; Rinaudo, M.; Del Tedesco, E.; Phelip, J.M.; Genin, C.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Paul, S. Development of an algorithm incorporating pharmacokinetics of adalimumab in inflammatory bowel diseases. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 109, 1250–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roblin, X.; Duru, G.; Williet, N.; Del Tedesco, E.; Cuilleron, M.; Jarlot, C.; Phelip, J.M.; Boschetti, G.; Flourié, B.; Nancey, S.; et al. Development and internal validation of a model using fecal calprotectin in combination with infliximab trough levels to predict clinical relapse in Crohn’s disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2017, 23, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roblin, X.; Marotte, H.; Leclerc, M.; Del Tedesco, E.; Phelip, J.M.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Paul, S. Combination of C-reactive protein, infliximab trough levels, and stable but not transient antibodies to infliximab are associated with loss of response to infliximab in inflammatory bowel disease. J. Crohn Colitis 2015, 9, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostholder, E.; Ahmed, A.; Cheifetz, A.S.; Moss, A.C. Outcomes after escalation of infliximab therapy in ambulatory patients with moderately active ulcerative colitis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2012, 35, 562–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubin, D.T.; Uluscu, O.; Sederman, R. Response to biologic therapy in Crohn’s disease is improved with early treatment: An analysis of health claims data. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2012, 18, 2225–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, E.A.; Harris, A.W.; Campbell, S.; Lindsay, J.; Hart, A.; Arebi, N.; Milestone, A.; Tsai, H.H.; Walters, J.; Carpani, M.; et al. Experience of maintenance infliximab therapy for refractory ulcerative colitis from six centres in England. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009, 29, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutka, M.; Bálint, A.; Farkas, K.; Palatka, K.; Lakner, L.; Miheller, P.; Rácz, I.; Hegede, G.; Vincze, Á.; Horváth, G.; et al. Long-term adalimumab therapy in ulcerative colitis in clinical practice: Result of the Hungarian multicenter prospective study. Orv. Hetil. 2016, 157, 706–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sandborn, W.J.; Sakuraba, A.; Wang, A.; Macaulay, D.; Reichmann, W.; Wang, S.; Chao, J.; Skup, M. Comparison of real-world outcomes of adalimumab and infliximab for patients with ulcerative colitis in the United States. Curr. Med Res. Opin. 2016, 32, 1233–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sartini, A.; Scaioli, E.; Liverani, E.; Bellanova, M.; Ricciardiello, L.; Bazzoli, F.; Belluzzi, A. Retention rate, persistence and safety of adalimumab in inflammatory bowel disease: A real-life, 9-year, single-center experience in Italy. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2019, 64, 863–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sazuka, S.; Katsuno, T.; Nakagawa, T.; Saito, M.; Saito, K.; Matsumura, T.; Arai, M.; Sato, T.; Yokosuka, O. Concomitant use of enteral nutrition therapy is associated with sustained response to infliximab in patients with Crohn’s disease. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 66, 1219–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnitzler, F.; Fidder, H.; Ferrante, M.; Noman, M.; Arijs, I.; Van Assche, G.; Hoffman, I.; Van Steen, K.; Vermeire, S.; Rutgeerts, P. Long-term outcome of treatment with infliximab in 614 patients with Crohn’s disease: Results from a single-centre cohort. Gut 2009, 58, 492–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.; Ye, B.D.; Song, E.M.; Lee, S.H.; Chang, K.; Lee, H.S.; Hwang, S.W.; Park, S.H.; Yang, D.H.; Kim, K.J.; et al. Long-term outcomes of adalimumab treatment in 254 patients with Crohn’s disease: A hospital-based cohort study from Korea. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2017, 62, 2882–2893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seow, C.H.; Newman, A.; Irwin, S.P.; Steinhart, A.H.; Silverberg, M.S.; Greenberg, G.R. Trough serum infliximab: A predictive factor of clinical outcome for infliximab treatment in acute ulcerative colitis. Gut 2010, 59, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapiro, J.M.; Subedi, S.; Machan, J.T.; Cerezo, C.S.; Ross, A.M.; Shalon, L.B.; Silverstein, J.A.; Herzlinger, M.I.; Kasper, V.; LeLeiko, N.S. Durability of infliximab is associated with disease extent in children with inflammatory bowel disease. J. Pediatric Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2016, 62, 867–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, M.; García-Alvarado, M.; Ferreiro, R.; Muñoz, F.; Barreiro-de Acosta, M. Efficacy of adalimumab treatment in steroid-dependent ulcerative colitis patients. Enferm. Inflamatoria Intest. 2016, 15, 44–49. [Google Scholar]

- Sprakes, M.B.; Ford, A.C.; Warren, L.; Greer, D.; Hamlin, J. Efficacy, tolerability, and predictors of response to infliximab therapy for Crohn’s disease: A large single centre experience. J. Crohn Colitis 2012, 6, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srinivasan, A.; Vasudevan, A.; McFarlane, A.; Sparrow, M.P.; Gibson, P.R.; Van Langenberg, D.R. Anti-TNF re-induction is as effective, simpler, and cheaper compared with dose interval shortening for secondary loss of response in Crohn’s disease. J. Crohn Colitis 2018, 12, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutharshan, K.; Gearry, R.B. Temporary adalimumab dose escalation is effective in Crohn’s disease patients with secondary non-response. J. Crohn Colitis 2013, 7, e277–e278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, Y.; Matsui, T.; Ito, H.; Ashida, T.; Nakamura, S.; Motoya, S.; Matsumoto, T.; Sato, N.; Ozaki, K.; Watanabe, M.; et al. Circulating interleukin 6 and albumin, and infliximab levels are good predictors of recovering efficacy after dose escalation infliximab therapy in patients with loss of response to treatment for Crohn’s disease: A prospective clinical trial. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2015, 21, 2114–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T.; Mizoshita, T.; Sugiyama, T.; Hirata, Y.; Kimura, Y.; Suzuki, Y.; Yamada, T.; Tsukamoto, H.; Mizushima, T.; Sugimura, N.; et al. Adalimumab dose-escalation therapy is effective in refractory Crohn’s disease patients with loss of response to adalimumab, especially in cases without previous infliximab treatment. Case Rep. Gastroenterol. 2019, 13, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y.; Motoya, S.; Hanai, H.; Hibi, T.; Nakamura, S.; Lazar, A.; Robinson, A.M.; Skup, M.; Mostafa, N.M.; Huang, B.; et al. Four-year maintenance treatment with adalimumab in Japanese patients with moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis. J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 52, 1031–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swoger, J.M.; Loftus, E.V., Jr.; Tremaine, W.J.; Faubion, W.A.; Pardi, D.S.; Kane, S.V.; Hanson, K.A.; Harmsen, W.S.; Zinsmeister, A.R.; Sandborn, W.J. Adalimumab for Crohn’s disease in clinical practice at Mayo clinic: The first 118 patients. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2010, 16, 1912–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tajiri, H.; Motoya, S.; Kinjo, F.; Maemoto, A.; Matsumoto, T.; Sato, N.; Yamada, H.; Nagano, M.; Susuta, Y.; Ozaki, K.; et al. Infliximab for pediatric patients with Crohn’s disease: A phase 3, open-label, uncontrolled, multicenter trial in Japan. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0201956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeuchi, I.; Kaburaki, Y.; Arai, K.; Shimizu, H.; Hirano, Y.; Nagata, S.; Shimizu, T. Infliximab for very early-onset inflammatory bowel disease: A tertiary center experience in Japan. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 35, 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taxonera, C.; Barreiro-de Acosta, M.; Calvo, M.; Saro, C.; Bastida, G.; Martín-Arranz, M.D.; Gisbert, J.P.; García-Sánchez, V.; Marín-Jiménez, I.; Bermejo, F.; et al. Infliximab dose escalation as an effective strategy for managing secondary loss of response in ulcerative colitis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2015, 60, 3075–3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taxonera, C.; Olivares, D.; Mendoza, J.L.; Díaz-Rubio, M.; Rey, E. Need for infliximab dose intensification in Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 9170–9177. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Taxonera, C.; Iglesias, E.; Muñoz, F.; Calvo, M.; Barreiro-de Acosta, M.; Busquets, D.; Calvet, X.; Rodríguez, A.; Pajares, R.; Gisbert, J.P.; et al. Adalimumab maintenance treatment in ulcerative colitis: Outcomes by prior anti-TNF use and efficacy of dose escalation. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2017, 62, 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taxonera, C.; Bertoletti, F.; Rodríguez, C.; Menchen, L.; Arribas, J.; Martínez-Montiel, P.; Sierra-Ausin, M.; Arias, L.; Rivero, M.; Juan, A.J.; et al. Real-life experience with golimumab in ulcerative colitis patients according to prior anti-TNF use. Gastroenterology 2016, 150, S979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taxonera, C.; Estellés, J.; Fernández-Blanco, I.; Merino, O.; Marín-Jiménez, I.; Barreiro-de Acosta, M.; Saro, C.; García-Sánchez, V.; Gento, E.; Bastida, G.; et al. Adalimumab induction and maintenance therapy for patients with ulcerative colitis previously treated with infliximab. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011, 33, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tighe, D.; Hall, B.; Jeyarajah, S.K.; Smith, S.; Breslin, N.; Ryan, B.; McNamara, D. One-year clinical outcomes in an IBD cohort who have previously had anti-TNFa trough and antibody levels assessed. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2017, 23, 1154–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkacz, J.; Lofland, J.H.; Vanderpoel, J.; Ruetsch, C. Infliximab dosing patterns in a sample of patients with Crohn’s disease: Results from a medical chart review. Am. Health Drug Benefits 2014, 7, 87–93. [Google Scholar]

- Tursi, A.; Elisei, W.; Faggiani, R.; Allegretta, L.; Valle, N.D.; Forti, G.; Franceschi, M.; Ferronato, A.; Gallina, S.; Larussa, T.; et al. Effectiveness and safety of adalimumab to treat outpatient ulcerative colitis: A real-life multicenter, observational study in primary inflammatory bowel disease centers. Medicine 2018, 97, e11897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahabnezhad, E.; Rabizadeh, S.; Dubinsky, M.C. A 10-year, single tertiary care center experience on the durability of infliximab in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2014, 20, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Assche, G.; Vermeire, S.; Ballet, V.; Gabriels, F.; Noman, M.; D’Haens, G.; Claessens, C.; Humblet, E.; Vande Casteele, N.; Gils, A.; et al. Switch to adalimumab in patients with Crohn’s disease controlled by maintenance infliximab: Prospective randomised SWITCH trial. Gut 2012, 61, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van de Vondel, S.; Baert, F.; Reenaers, C.; Vanden Branden, S.; Amininejad, L.; Dewint, P.; Van Moerkercke, W.; Rahier, J.F.; Hindryckx, P.; Bossuyt, P.; et al. Incidence and predictors of success of adalimumab dose escalation and de-escalation in ulcerative colitis: A real-world belgian cohort study. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2018, 24, 1099–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vatansever, A.; Çekiç, C.; Ekinci, N.; Yüksel, E.S.; Avcı, A.; Aslan, F.; Arabul, M.; Ünsal, B.; Çakalağaoğlu, F. Effects of mucosal TNF-alpha levels on treatment response in Crohn’s disease patients receiving anti-TNF treatment. Hepato Gastroenterol. 2014, 61, 2277–2282. [Google Scholar]

- Verstockt, B.; Moors, G.; Bian, S.; Van Stappen, T.; Van Assche, G.; Vermeire, S.; Gils, A.; Ferrante, M. Influence of early adalimumab serum levels on immunogenicity and long-term outcome of anti-TNF naive Crohn’s disease patients: The usefulness of rapid testing. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 48, 731–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viazis, N.; Koukouratos, T.; Anastasiou, J.; Giakoumis, M.; Triantos, C.; Tsolias, C.; Theocharis, G.; Karamanolis, D.G. Azathioprine discontinuation earlier than 6 months in Crohn’s disease patients started on anti-TNF therapy is associated with loss of response and the need for anti-TNF dose escalation. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 27, 436–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, M.; Hibi, T.; Mostafa, N.M.; Chao, J.; Arora, V.; Camez, A.; Petersson, J.; Thakkar, R. Long-term safety and efficacy of adalimumab in Japanese patients with moderate to severe Crohn’s disease. J. Crohn Colitis 2014, 8, 1407–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, R.L.; Zelinkova, Z.; Wolbink, G.J.; Kuipers, E.J.; Stokkers, P.C.; van der Woude, C.J. Immunogenicity negatively influences the outcome of adalimumab treatment in Crohn’s disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2008, 28, 1122–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, D.; D’Haens, G.; Sandborn, W.J.; Colombel, J.F.; Van Assche, G.; Robinson, A.M.; Lazar, A.; Zhou, Q.; Petersson, J.; Thakkar, R.B. Escalation to weekly dosing recaptures response in adalimumab-treated patients with moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2014, 40, 486–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, S.; Yoshino, T.; Matsuura, M.; Minami, N.; Toyonaga, T.; Honzawa, Y.; Tsuji, Y.; Nakase, H. Long-term efficacy of infliximab for refractory ulcerative colitis: Results from a single center experience. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014, 14, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokoyama, K.; Yamazaki, K.; Katafuchi, M.; Ferchichi, S. A retrospective claims database study on drug utilization in Japanese patients with Crohn’s disease treated with adalimumab or infliximab. Adv. Ther. 2016, 33, 1947–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, N.S.; Hart, A.; De Cruz, P. Systematic review: Predicting and optimising response to anti-TNF therapy in Crohn’s disease-algorithm for practical management. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2016, 43, 30–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Horin, S.; Chowers, Y. Review article: Loss of response to anti-TNF treatments in Crohn’s disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011, 33, 987–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandborn, W.J.; Colombel, J.F.; Schreiber, S.; Plevy, S.E.; Pollack, P.F.; Robinson, A.M.; Chao, J.; Mulani, P. Dosage adjustment during long-term adalimumab treatment for Crohn’s disease: Clinical efficacy and pharmacoeconomics. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2011, 17, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisbert, J.P.; Panés, J. Loss of response and requirement of infliximab dose intensification in Crohn’s disease: A review. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2009, 104, 760–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billioud, V.; Sandborn, W.J.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L. Loss of response and need for adalimumab dose intensification in Crohn’s disease: A systematic review. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 106, 674–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Chen, B.L.; Mao, R.; Zhang, S.H.; He, Y.; Zeng, Z.R.; Ben-Horin, S.; Chen, M.H. Systematic review with meta-analysis: Loss of response and requirement of anti-TNFα dose intensification in Crohn’s disease. J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 52, 535–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gemayel, N.C.; Rizzello, E.; Atanasov, P.; Wirth, D.; Borsi, A. Dose escalation and switching of biologics in ulcerative colitis: A systematic literature review in real-world evidence. Curr. Med Res. Opin. 2019, 35, 1911–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaparro, M.; Panes, J.; Garcia, V.; Merino, O.; Nos, P.; Domenech, E.; Penalva, M.; Garcia-Planella, E.; Esteve, M.; Hinojosa, J.; et al. Long-term durability of response to adalimumab in Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012, 18, 685–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Huang, V.; Fedorak, D.K.; Kroeker, K.I.; Dieleman, L.A.; Halloran, B.P.; Fedorak, R.N. Crohn’s disease outpatients treated with adalimumab have an earlier secondary loss of response and requirement for dose escalation compared to infliximab: A real life cohort study. J. Crohn Colitis 2014, 8, 1454–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, B.N.; Pellish, R.S.; Thompson, K.D.; Baptista, V.; Siegel, C.A. Using therapeutic drug monitoring to identify variable infliximab metabolism in an individual patient with ulcerative colitis. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2016, 50, 66–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandse, J.F.; van den Brink, G.R.; Wildenberg, M.E.; van der Kleij, D.; Rispens, T.; Jansen, J.M.; Mathôt, R.A.; Ponsioen, C.Y.; Löwenberg, M.; D’Haens, G.R. Loss of infliximab into feces is associated with lack of response to therapy in patients with severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 2015, 149, 350–355.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kevans, D.; Murthy, S.; Mould, D.R.; Silverberg, M.S. Accelerated clearance of infliximab is associated with treatment failure in patients with corticosteroid-refractory acute ulcerative colitis. J. Crohn Colitis 2018, 12, 662–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author and Year | Study Design | Population | Medical Condition | Anti-TNF | Prior Anti-TNF | FOLLOW up (Months) | n | N | DI Rate (%) | Intensification Regimen | Response/Remission | n’ | N’ | DI Efficacy (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Afif 2009 [25] | P | A | UC | ADA | Naïve and non-naïve | 6 | 7 | 20 | 35 | |||||

| 2 | Albisi 2019 [26] | R | C | CD | ADA | Non-naïve | 12 | 3 | 44 | 7 | ID | Response | 2 | 3 | 67 |

| 3 | Armuzzi 2013 [27] | R | A | UC | ADA | Naïve and non-naïve | 12 | 31 | 88 | 35 | |||||

| 4 | Assa 2013 [28] | R | C | UC+CD | IFX+ADA | - | 20 | 10 | 102 | 10 | |||||

| 5 | Baert 2014 [29] | R | A | UC | ADA | Non-naïve | 12 | 22 | 73 | 30 | |||||

| 6 | Baert 2013 [30] | R | A | CD | ADA | Naïve and non-naïve | 14 | 208 | 605 | 34 | RI | Response | 139 | 208 | 67 |

| CD | ADA | Naïve | 14 | 40 | 208 | 19 | |||||||||

| CD | ADA | Non-naïve | 14 | 164 | 365 | 45 | |||||||||

| 7 | Baki 2015 [31] | R | A | UC | IFX | Naïve and non-naïve | 5 | 26 | 54 | 48 | |||||

| UC | ADA | Naïve and non-naïve | 4 | 17 | 37 | 46 | |||||||||

| 8 | Balint 2018 [32] | P | A | UC | IFX | Naïve | 12 | 20 | 61 | 33 | |||||

| 9 | Balint 2016 [33] | P | A+C | UC | ADA | Naïve and non-naïve | 12 | 13 | 73 | 18 | |||||

| 10 | Bhalme 2013 [34] | R | A | CD | IFX | Naïve | 13 | 4 | 76 | 5 | |||||

| ADA | Naïve | 11 | 2 | 15 | 13 | ||||||||||

| ADA | Non-naïve | 11 | 9 | 39 | 23 | ||||||||||

| ADA | Naïve and non-naïve | 11 | 11 | 54 | 20 | ||||||||||

| 11 | Black 2016 [35] | R | A | UC | ADA | Naïve | 12 | 66 | 155 | 43 | |||||

| ADA | Non-naïve | 12 | 17 | 36 | 47 | ||||||||||

| 12 | Bor 2017 [36] | R | A | CD | IFX | Naïve and non-naïve | - | 14 | 48 | 29 | ID | Remission | 3 | 14 | 21 |

| 13 | Bortlik 2013 [37] | R | A | CD | IFX | Naïve and non-naïve | 24 | 6 | 84 | 7 | |||||

| 14 | Bossuyt 2019 [38] | P | A | UC | GOL | Naïve and non-naïve | 6 | 8 | 91 | 9 | |||||

| 15 | Bouguen 2015 [39] | P | A | CD | ADA | Naïve and non-naïve | - | Response | 23 | 42 | 55 | ||||

| Remission | 14 | 42 | 33 | ||||||||||||

| 16 | Bramuzzo 2019 [40] | R | C | UC+CD | IFX | Naïve | 12 | 44 | 172 | 26 | |||||

| 17 | Brandes 2019 [41] | R | A | UC+CD | ADA | Naïve and non-naïve | 12 | 76 | 502 | 15 | |||||

| 18 | Bultman 2012 [42] | P | A | CD | ADA | Naïve | 12 | 23 | 49 | 47 | - | Response | 20 | 46 | 43 |

| CD | ADA | Non-naïve | 12 | 23 | 73 | 31.5 | |||||||||

| 19 | Cameron 2015 [43] | R | C | UC+CD | IFX | Naïve | 23 | 23 | 72 | 32 | |||||

| UC+CD | ADA | Naïve and non-naïve | 14 | 19 | 29 | 66 | |||||||||

| 20 | Casanova 2019 [21] | R | A | UC+CD | IFX+ADA+CZP | Non-naïve | 18 | 230 | 1122 | 20.5 | RI or ID | Remission | 161 | 230 | 42 |

| 21 | Casellas 2015 [44] | P | A | CD | ADA | Naïve and non-naïve | 36 | 3 | 28 | 11 | |||||

| 22 | Castaño 2015 [45] | R | A | CD | ADA | Naïve | 12 | 9 | 46 | 20 | RI | Remission | 3 | 9 | 33 |

| 23 | Caviglia 2007 [46] | R | A | UC | IFX | - | 24 | 0 | 10 | 0 | |||||

| CD | IFX | - | 24 | 3 | 40 | 7.5 | |||||||||

| 24 | Cesarini 2014 [47] | R | A | UC | IFX | Naïve | 24 | RI or ID | Response | 37 | 41 | 90 | |||

| Remission | 19 | 41 | 46 | ||||||||||||

| RI | Response | 24 | 26 | 92 | |||||||||||

| Remission | 9 | 26 | 35 | ||||||||||||

| ID | Response | 13 | 15 | 87 | |||||||||||

| Remission | 10 | 15 | 67 | ||||||||||||

| 25 | Chaparro 2011 [48] | R | A | CD | IFX | Naïve | 41 | 127 | 309 | RI + ID | Response | 122 | 127 | 96 | |

| Remission | 71 | 127 | 56 | ||||||||||||

| 26 | Chaparro 2012 [49] | R | A | CD | IFX | Naïve | 22 | 33 | 197 | 17 | - | Response | 26 | 33 | 79 |

| Remission | 11 | 33 | 33 | ||||||||||||

| 27 | Cheng, 2017 [50] | R | C | UC | IFX | Naïve | 24 | 60 | 113 | 53 | RI or ID | Response | 36 | 60 | 60 |

| CD | IFX | Naïve | 24 | 19 | 35 | 54 | RI or ID | Response | 12 | 35 | 34 | ||||

| 28 | Choi 2014 [51] | R | A | CD | ADA | Naïve | 18 | 5 | 36 | 14 | |||||

| IFX | Naïve | 18 | 0 | 36 | 0 | ||||||||||

| 29 | Choi 2017 [52] | R | C | CD | IFX | Naïve | 16 | 14 | 29 | 48 | RI or ID | Response | 17 | 21 | 80 |

| UC | IFX | Naïve | 16 | 7 | 10 | 70 | |||||||||

| 30 | Church 2014 [53] | R | C | CD | IFX | Naïve | 21 | 79 | 157 | 50 | |||||

| 31 | Clark 2019 [54] | R | A | CD | IFX | Non-naïve | 24 | 10 | 17 | 59 | |||||

| 32 | Cohen 2012 [55] | R | A | CD | ADA | Naïve and non-naïve | 55 | 31 | 75 | 41 | |||||

| 33 | Cordero 2011 [56] | P | A | CD | ADA | Non-naïve | 12 | 18 | 25 | 72 | |||||

| 34 | DeRidder 2008 [57] | R | C | CD | IFX | Naïve | 41 | 40 | 66 | 61 | |||||

| 35 | DeBruyn 2017 [58] | R | C | CD | IFX | Naïve | 19 | 102 | 178 | 57 | |||||

| 36 | D’Haens 2018 [10] | P | A | CD | IFX | Naïve | 12 | 16 | 40 | 40 | |||||

| 37 | Dignass 2019 [17] | R | A | UC | IFX | Naïve | 24 | 75 | 114 | 66 | |||||

| UC | ADA | Naïve | 24 | 49 | 125 | 39 | |||||||||

| UC | GOL | Naïve | 24 | 27 | 47 | 57 | |||||||||

| 38 | Dreesen 2018 [59] | R | A | CD | IFX | Naïve | RI, ID, RI+ID | Response | 65 | 103 | 63 | ||||

| ID | Response | 24 | 45 | 53 | |||||||||||

| RI | Response | 33 | 45 | 73 | |||||||||||

| RI + ID | Response | 8 | 13 | 61 | |||||||||||

| 39 | Dubinsky 2016 [60] | P | C | CD | ADA | Naïve and non-naïve | 12 | 35 | 93 | 38 | RI | Response | 20 | 35 | 57 |

| RI | Remission | 11 | 35 | 31 | |||||||||||

| Naïve | 12 | 18 | 51 | 35 | RI | Response | 13 | 18 | 72 | ||||||

| RI | Remission | 5 | 18 | 28 | |||||||||||

| Non-naïve | 12 | 17 | 42 | 40 | RI | Response | 7 | 17 | 41 | ||||||

| RI | Remission | 3 | 17 | 18 | |||||||||||

| 40 | Dumitrescu 2015 [61] | R | A | UC | IFX | Naïve | RI or ID | Response | 87 | 157 | 55 | ||||

| Remission | 28 | 157 | 18 | ||||||||||||

| 41 | Dupont 2016 [62] | R | C | CD | IFX | Naïve | - | 65 | 187 | 35 | |||||

| 42 | Duveau 2016 [63] | R | A | CD | ADA | Naïve and non-naïve | - | 124 | 430 | 29 | RI or ID | Response | 99 | 124 | 80 |

| 43 | Echarri 2015 [64] | P | A | CD | ADA | Naïve | 24 | 12 | 68 | 18 | RI | Remission | 9 | 12 | 75 |

| 44 | Falaiye 2014 [65] | R | A | UC+CD | IFX | Naïve | 12 | 18 | 29 | 62 | RI or ID | Response | 7 | 18 | 39 |

| 45 | Fernandes 2019 [66] | R | A | UC+CD | IFX | Naïve and non-naïve | 12 | 25 | 149 | 17 | |||||

| UC+CD | IFX | Naïve and non-naïve | 24 | 38 | 149 | 25.5 | |||||||||

| 46 | Fernández-Salazar 2015 [67] | R | A | UC | IFX | Naïve | 38 | 53 | 144 | 37 | |||||

| 47 | Fiorino 2017 [68] | P | A+C | UC+CD | IFX | Naïve and non-naïve | 3 | 74 | 399 | 16 | |||||

| 48 | Fortea-Ormaechea 2011 [69] | R | A | CD | ADA | Naïve and non-naïve | 9 | 57 | 174 | 33 | |||||

| 49 | Frederiksen 2014 [70] | R | A | UC+CD | ADA | No naïve | 9 | 21 | 57 | 37 | |||||

| 50 | García bosch 2013 [71] | R | A | UC | ADA | Naïve and non-naïve | 12 | 18 | 48 | 37.5 | - | Response | 15 | 18 | 83 |

| - | Remission | 8 | 18 | 44 | |||||||||||

| 51 | Ghaly 2015 [72] | R | A | CD | IFX+ADA | Naïve and non-naïve | 40 | 73 | - | Response | 40 | 73 | 55 | ||

| 52 | Gofin 2019 [73] | R | C | CD | IFX+ADA | Naïve | 19 | 18 | 98 | 18 | |||||

| 53 | Gonczi 2017 [74] | P | A | UC+CD | ADA | Naïve and non-naïve | 12 | 22 | 112 | 20 | |||||

| 24 | 33 | 112 | 29 | ||||||||||||

| 54 | Gonzaga 2009 [75] | R | A | CD | IFX | Naïve | 49 | 56 | 111 | 50 | |||||

| 55 | González Lama 2008 [76] | R | A | CD | IFX | Naïve | 28 | 15 | 114 | 13 | RI or ID | Response | 10 | 15 | 67 |

| 56 | Grover 2014 [77] | R | C | CD | IFX | Naïve | 12 | 13 | 47 | 28 | - | Response | 7 | 13 | 54 |

| 57 | Guerbau 2017 [78] | P | A | CD | IFX | Naïve and non-naïve | 12 | 43 | 140 | 30 | |||||

| 58 | Guidi 2018 [79] | P | A | UC+CD | IFX | Naïve | 3 | 37 | 52 | 71 | |||||

| 59 | Ho 2008 [80] | R | A | CD | ADA | Non-naïve | 12 | 13 | 22 | 59 | |||||

| 60 | Ho 2009 [81] | R | A+C | CD | ADA | Naïve and non-naïve | 6 | 24 | 98 | 24 | |||||

| CD | ADA | Naïve | 12 | 2 | 10 | 20 | |||||||||

| CD | ADA | Non-naïve | 12 | 28 | 88 | 32 | |||||||||

| CD | ADA | Naïve and non-naïve | 24 | 54 | 98 | 55 | |||||||||

| 61 | Hussey 2016 [82] | R | A | UC | ADA | Naïve and non-naïve | 19 | 13 | 55 | 24 | |||||

| 62 | Hyams 2010 [83] | P | C | UC | IFX | Naïve | 30 | 11 | 34 | 33 | |||||

| 63 | Hyams 2007 [11] | P | C | CD | IFX | Naïve | 12 | 9 | 52 | 17 | ID | Response | 5 | 9 | 56 |

| 64 | Iborra 2017 [84] | R | A | UC | ADA | Naïve and non-naïve | 12 | 93 | 263 | 35 | |||||

| ADA | Naïve | 12 | 21 | 87 | 24 | ||||||||||

| ADA | Non-naïve | 12 | 72 | 176 | 41 | ||||||||||

| 65 | Inokuchi 2019 [85] | R | A | CD | IFX | Naïve | 83 | 54 | 183 | 29.5 | |||||

| CD | ADA | Naïve | 43 | 6 | 80 | 7.5 | |||||||||

| 66 | Juillerat 2015 [86] | R | A | CD | IFX | Naïve and non-naïve | - | 77 | 250 | 31 | |||||

| 67 | Juliao 2013 [87] | R | A | UC | IFX | Naïve | 27 | 4 | 28 | 14 | RI | Response | 4 | 4 | 100 |

| 68 | Kang 2016 [88] | P | C | CD | IFX | Naïve | 12 | 7 | 72 | 10 | |||||

| 69 | Karmiris 2009 [89] | P | A | CD | ADA | Non-naïve | 20 | 102 | 156 | 65 | RI | Response | 73 | 102 | 72 |

| 70 | Katz 2012 [90] | R | A | CD | IFX | Naïve | - | RI or ID | Response | 123 | 168 | 73 | |||

| RI | Response | 37 | 56 | 66 | |||||||||||

| ID | Response | 86 | 112 | 77 | |||||||||||

| 71 | Kelly 2017 [91] | R | A | UC+CD | IFX | Naïve | RI or ID | Response | 82 | 143 | 57 | ||||

| Remission | 69 | 143 | 48 | ||||||||||||

| 72 | Kierkus 2015 [12] | P | C | CD | IFX | Naïve | 12 | 16 | 84 | 19 | |||||

| 73 | Kiss 2011 [92] | R | A | CD | ADA | Naïve and non-naïve | 12 | 33 | 201 | 16 | |||||

| 74 | Knyazev 2018 [22] | P | A | CD | CRP | Naïve and non-naïve | 24 | 3 | 39 | 8 | |||||

| 75 | Knyazev 2016 [93] | R | A | UC | IFX | Naïve | - | 5 | 45 | 11 | - | Remission | 4 | 5 | 80 |

| 76 | Knyazev 2017 [94] | P | A | CD | ADA | Naïve and non-naïve | 28 | 6 | 70 | 9 | |||||

| 77 | Kopylov 2011 [95] | R | A | CD | IFX | Naïve | RI | Response | 38 | 55 | 70 | ||||

| CD | IFX | Naïve | ID | Response | 26 | 39 | 67 | ||||||||

| 78 | Kunovski 2020 [96] | R | A | UC | IFX | Naïve | 12 | 43 | 396 | 11 | |||||

| ADA | Naïve | 12 | 34 | 172 | 20 | ||||||||||

| 79 | Lam 2014 [97] | R | A | CD | IFX | Naïve | 12 | 34 | 68 | 50 | |||||

| 80 | Lees 2009 [98] | R | A+C | UC+CD | ADA | Non-naïve | 12 | 16 | 30 | 53 | |||||

| 81 | Lin 2012 [99] | R | A | CD | IFX | Naïve | 60 | 34 | 94 | 36 | RI or ID | Response | 24 | 30 | 80 |

| 82 | Lindsay 2013 [100] | R | A+C | CD | IFX | Naïve | 12 | 9 | 380 | 2 | |||||

| IFX | Naïve | 24 | 19 | 380 | 5 | ||||||||||

| 83 | Lindsay 2017 [101] | R | A | UC | IFX+ADA | 24 | 139 | 538 | 26 | ||||||

| CD | IFX+ADA | Naïve | 24 | 126 | 657 | 19 | |||||||||

| 84 | Ling 2018 [102] | R | C | CD | IFX | Naïve | 24 | 26 | 43 | 60 | RI or ID | Response | 14 | 26 | 54 |

| 85 | Llaó 2016 [103] | P | A | UC | IFX | - | 18 | 8 | 15 | 53 | |||||

| 86 | Lofberg 2012 [104] | P | A | CD | ADA | Naïve and non-naïve | 5 | 131 | 945 | 14 | RI | Remission | 46 | 131 | 35 |

| 87 | Lopez Palacios 2008 [105] | R | A | CD | ADA | Non-naïve | 24 | 6 | 22 | 27 | RI | Response | 4 | 6 | 66 |

| 88 | Ma 2015 [106] | R | A | UC | IFX | Naïve | 158 | 36 | 66 | 54 | |||||

| UC | ADA | Naïve | 139 | 18 | 36 | 50 | |||||||||

| 89 | Ma 2014 [107] | R | A | CD | IFX | Naïve | 40 | 60 | 117 | 51 | |||||

| CD | ADA | Naïve | 28 | 23 | 38 | 61 | |||||||||

| CD | ADA | Non-naïve | 28 | 41 | 63 | 65 | |||||||||

| 90 | Ma 2016 [108] | R | A | CD | IFX+ADA | Naïve | 38 | 116 | 190 | 61 | |||||

| 91 | Ma 2014 (bis) [109] | R | A | CD | ADA | Naïve and non-naïve | - | - | Response | 74 | 92 | 80 | |||

| 92 | Magro 2014 [110] | R | A | CD | IFX | Naïve | 84 | 55 | 163 | 34 | |||||

| UC | IFX | Naïve | 84 | 19 | 52 | 37 | |||||||||

| 93 | Martineau 2017 [19] | R | A | CD | GOL | Non-naïve | 18 | 51 | 115 | 44 | - | Response | 27 | 51 | 53 |

| 94 | Merras 2016 [20] | P | C | CD | GOL | Non-naïve | * | 1 | 6 | 17 | |||||

| 95 | Molnar 2012 [111] | R | A | CD | IFX | Naïve | 12 | 3 | 35 | 9 | |||||

| CD | ADA | Naïve | 12 | 3 | 10 | 30 | |||||||||

| CD | ADA | Non-naïve | 12 | 13 | 16 | 81 | |||||||||

| 96 | Moon 2015 [23] | R | A | CD | CZP | Naïve and non-naïve | 26 | 43 | 358 | 12 | |||||

| 97 | Motoya 2018 [112] | P | A+C | CD | ADA | Naïve and non-naïve | RI | Response | 16 | 28 | 57 | ||||

| CD | ADA | Naïve and non-naïve | RI | Remission | 10 | 28 | 35 | ||||||||

| ADA | Naïve | RI | Response | 6 | 9 | 67 | |||||||||

| ADA | Naïve | RI | Remission | 5 | 9 | 56 | |||||||||

| ADA | Non-naïve | RI | Response | 10 | 19 | 53 | |||||||||

| ADA | Non-naïve | RI | Remission | 5 | 19 | 26 | |||||||||

| 98 | Moroi 2019 [113] | R | A | CD | IFX | Naïve | 36 | 17 | 62 | 27 | |||||

| ADA | Naïve | 36 | 0 | 7 | 0 | ||||||||||

| 99 | Murthy 2015 [114] | R | A | UC | IFX | Naïve | 12 | 59 | 116 | 51 | |||||

| 100 | Narula 2016 [115] | P | A | CD | IFX | Naïve | 24 | 35 | 251 | 14 | |||||

| CD | ADA | Naïve | 24 | 9 | 111 | 8 | |||||||||

| 101 | Nedelkopoulou 2018 [116] | R | C | UC | IFX | Naïve | 20 | 2 | 10 | 20 | |||||

| 102 | Ng 2009 [117] | P | A | CD | ADA | Non-naïve | 12 | 2 | 7 | 29 | RI | Response | 2 | 2 | 100 |

| 103 | Nichita 2010 [118] | R | A | CD | ADA | Naïve and non-naïve | 12 | 13 | 55 | 24 | RI or ID | Response | 8 | 13 | 62 |

| Remission | 6 | 13 | 46 | ||||||||||||

| 104 | Nuti 2014 [119] | R | C | CD | IFX+ADA | Naïve and non-naïve | 36 | 27 | 78 | 35 | |||||

| 105 | O’Donnell 2015 [120] | R | A+C | CD | IFX | Naïve | 36 | 133 | 287 | 46 | |||||

| UC | IFX | Naïve | 36 | 84 | 125 | 67 | |||||||||

| 106 | Olivares 2019 [121] | P | A | UC+CD | ADA | Naïve | 18. | 15 | 33 | 45 | |||||

| UC+CD | ADA | Non-naïve | 18. | 37 | 53 | 70 | |||||||||

| UC | ADA | Naïve and non-naïve | 6. | 7 | 43 | 16 | |||||||||

| CD | ADA | Naïve and non-naïve | 6. | 21 | 43 | 49 | |||||||||

| UC | ADA | Naïve and non-naïve | 18. | 24 | 43 | 56 | |||||||||

| CD | ADA | Naïve and non-naïve | 20. | 28 | 43 | 65 | |||||||||

| 107 | Orlando 2012 [122] | P | A | CD | ADA | Naïve and non-naïve | 14. | 15 | 110 | 14 | |||||

| 108 | Osterman 2017 [123] | R | A | CD | IFX | Naïve | 12 | 42 | 381 | 11 | |||||

| ADA | Naive | 12 | 16 | 196 | 8 | ||||||||||

| 109 | Oussalah 2009 [124] | R | A | CD | ADA | Non-naïve | 36 | 7 | 53 | 13 | RI | Remission | 6 | 7 | 86 |

| 110 | Oussalah 2010 [125] | R | A | UC | IFX | Naïve | 18 | 36 | 80 | 45 | |||||

| 111 | Panaccione 2010 [126] | P | A | CD | ADA | Naïve | 12 | 71 | 260 | 27 | |||||

| 24 | 105 | 260 | 40 | ||||||||||||

| 112 | Paredes 2020 [127] | P | A | UC+CD | IFX | Naïve | 12 | 2 | 31 | 6 | |||||

| UC+CD | IFX | Naïve | 24 | 12 | 31 | 39 | - | Response | 6 | 12 | 50 | ||||

| UC | IFX | Naïve | 24 | 3 | 31 | 10 | |||||||||

| CD | IFX | Naïve | 24 | 9 | 31 | 29 | |||||||||

| 113 | Pariente 2012 [128] | R | A | UC+CD | IFX | Naïve | RI or ID | Response | 27 | 39 | 69 | ||||

| 114 | Park 2016 [129] | R | A | CD | IFX | Naïve | 36 | 86 | 582 | 15 | |||||

| 115 | Patel 2017 [130] | R | A | CD | IFX+ADA+ CZP+GOL | Naïve | 6 | 640 | 4569 | 14 | |||||

| Naïve | 12 | 1097 | 4569 | 24 | |||||||||||

| Naïve | 24 | 1553 | 4569 | 34 | |||||||||||

| Naïve | 36 | 1782 | 4569 | 39 | |||||||||||

| UC | IFX+ADA+ CZP+GOL | Naïve | 6 | 272 | 1699 | 16 | |||||||||

| Naïve | 12 | 475 | 1699 | 28 | |||||||||||

| Naïve | 24 | 680 | 1699 | 40 | |||||||||||

| Naïve | 36 | 748 | 1699 | 44 | |||||||||||

| 116 | Paul 2013 [131] | P | A | UC+CD | IFX | Naïve and non-naïve | ID | Remission | 30 | 52 | 58 | ||||

| 117 | Peters 2014 [132] | R | A | CD | ADA | Naïve | 24 | 45 | 167 | 27 | |||||

| CD | ADA | Non-naïve | 24 | 135 | 271 | 50 | |||||||||

| 118 | Peyrin 2007 [133] | P | A | CD | ADA | Non-naïve | 12 | 6 | 24 | 25 | |||||

| 119 | Pollinger 2019 [134] | R | A | UC | ADA | Naïve | 12 | 48 | 154 | 31 | |||||

| 120 | Preda 2016 [135] | R | A | CD | IFX | Naïve | 36 | 26 | 129 | 20 | - | Remission | 11 | 26 | 42 |

| CD | ADA | Naïve | 20 | 19 | 136 | 14 | - | Remission | 16 | 19 | 84 | ||||

| 121 | Qazi 2016 [136] | P | A | UC+CD | IFX | Naïve | 24 | 10 | 75 | 13 | |||||

| 122 | Regueiro 2007 [137] | R | A | CD | IFX | Naïve and non-naïve | 30 | 54 | 108 | 50 | RI or ID | Response | 41 | 54 | 76 |