The Combination of Clindamycin and Gentamicin Is Adequate for Pelvic Inflammatory Disease: A Retrospective Cohort Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

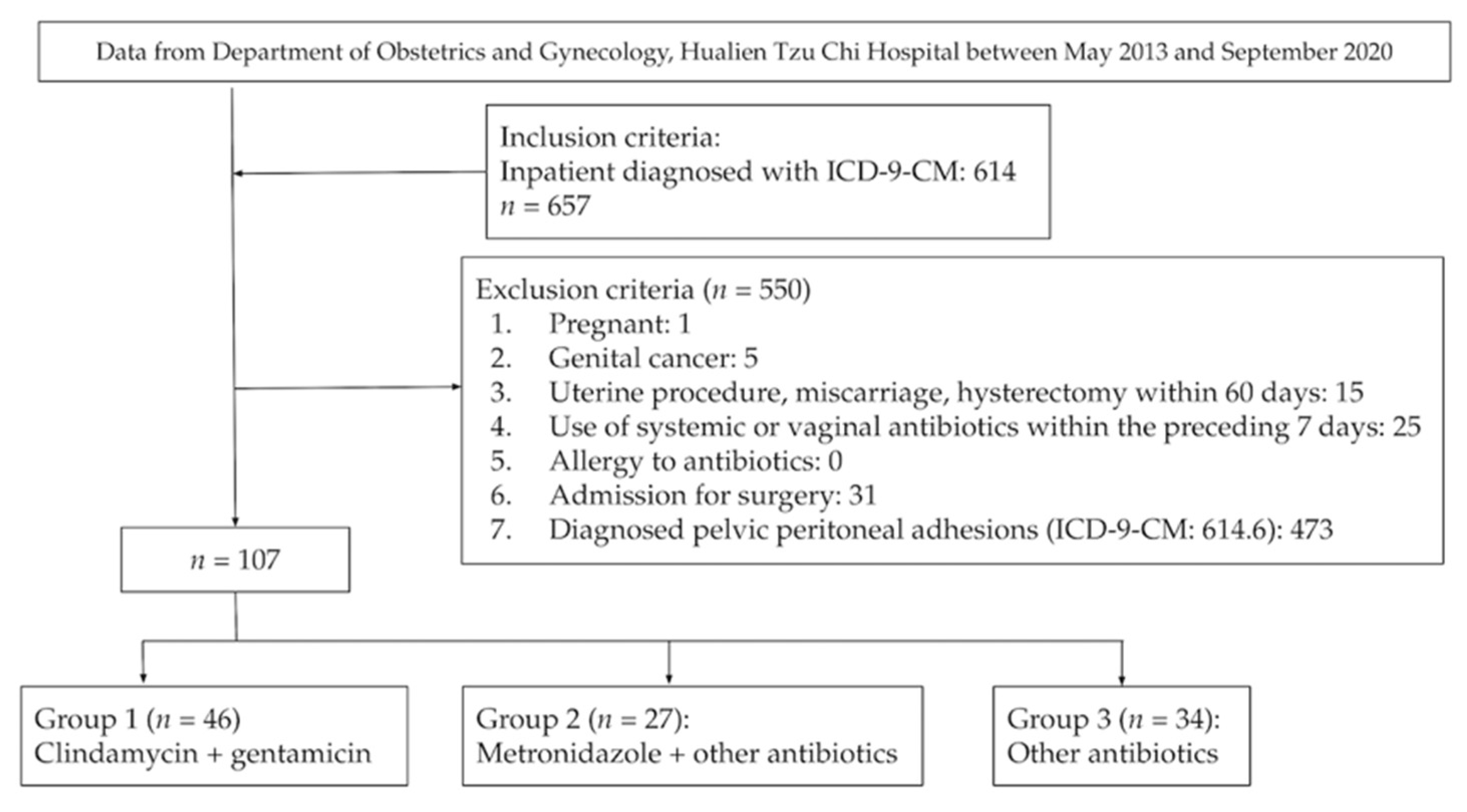

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Outcome Measurement

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barrett, S.; Taylor, C. A Review on Pelvic Inflammatory Disease. Int. J. STD AIDS 2005, 16, 715–720, quiz 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savaris, R.F.; Fuhrich, D.G.; Duarte, R.V.; Franik, S.; Ross, J. Antibiotic Therapy for Pelvic Inflammatory Disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.-C.; Huang, C.-C.; Lin, S.-Y.; Chang, C.Y.-Y.; Lin, W.-C.; Chung, C.-H.; Lin, F.-H.; Tsao, C.-H.; Lo, C.-M.; Chien, W.-C. Association of Pelvic Inflammatory Disease (PID) with Ectopic Pregnancy and Preterm Labor in Taiwan: A Nationwide Population-Based Retrospective Cohort Study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0219351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreisel, K.; Torrone, E.; Bernstein, K.; Hong, J.; Gorwitz, R. Prevalence of Pelvic Inflammatory Disease in Sexually Experienced Women of Reproductive Age—United States, 2013–2014. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2017, 66, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haggerty, C.L.; Hillier, S.L.; Bass, D.C.; Ness, R.B. PID Evaluation and Clinical Health study investigators Bacterial Vaginosis and Anaerobic Bacteria Are Associated with Endometritis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2004, 39, 990–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haggerty, C.L.; Totten, P.A.; Tang, G.; Astete, S.G.; Ferris, M.J.; Norori, J.; Bass, D.C.; Martin, D.H.; Taylor, B.D.; Ness, R.B. Identification of Novel Microbes Associated with Pelvic Inflammatory Disease and Infertility. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2016, 92, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Pelvic Inflammatory Disease (PID). Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/pid.htm (accessed on 22 June 2021).

- Ross, J.; Guaschino, S.; Cusini, M.; Jensen, J. 2017 European Guideline for the Management of Pelvic Inflammatory Disease. Int. J. STD AIDS 2018, 29, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiesenfeld, H.C.; Meyn, L.A.; Darville, T.; Macio, I.S.; Hillier, S.L. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Ceftriaxone and Doxycycline, with or Without Metronidazole, for the Treatment of Acute Pelvic Inflammatory Disease. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 72, 1181–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savaris, R.F.; Fuhrich, D.G.; Duarte, R.V.; Franik, S.; Ross, J.D.C. Antibiotic Therapy for Pelvic Inflammatory Disease: An Abridged Version of a Cochrane Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2019, 95, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pankuch, G.A.; Jacobs, M.R.; Appelbaum, P.C. Susceptibilities of 428 Gram-Positive and -Negative Anaerobic Bacteria to Bay y3118 Compared with Their Susceptibilities to Ciprofloxacin, Clindamycin, Metronidazole, Piperacillin, Piperacillin-Tazobactam, and Cefoxitin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1993, 37, 1649–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baron, E.J.; Ropers, G.; Summanen, P.; Courcol, R.J. Bactericidal Activity of Selected Antimicrobial Agents against Bilophila Wadsworthia and Bacteroides Gracilis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1993, 16 (Suppl. S4), S339–S343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuchural, G.J., Jr.; Tally, F.P.; Jacobus, N.V.; Gorbach, S.L.; Aldridge, K.; Cleary, T.; Finegold, S.M.; Hill, G.; Iannini, P.; O’Keefe, J.P. Antimicrobial Susceptibilities of 1292 Isolates of the Bacteroides Fragilis Group in the United States: Comparison of 1981 with 1982. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1984, 26, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savaris, R.F.; Ross, J.; Fuhrich, D.G.; Rodriguez-Malagon, N.; Duarte, R.V. Antibiotic Therapy for Pelvic Inflammatory Disease (PID). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorbye, I.K.; Jerve, F. Anne Catherine Staff Reduction in Hospitalized Women with Pelvic Inflammatory Disease in Oslo over the Past Decade. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 2005, 60, 362–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, M.; Breitkopf, D.; Waud, K. Tubo-Ovarian Abscess Management Options for Women Who Desire Fertility. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 2009, 64, 681–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munro, K.; Gharaibeh, A.; Nagabushanam, S.; Martin, C. Diagnosis and Management of Tubo-Ovarian Abscesses. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2018, 20, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeeley, S.G.; Hendrix, S.L.; Mazzoni, M.M.; Kmak, D.C.; Ransom, S.B. Medically Sound, Cost-Effective Treatment for Pelvic Inflammatory Disease and Tuboovarian Abscess. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1998, 178, 1272–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry-Suchet, J. Laparoscopic Treatment of Tubo-Ovarian Abscess: Thirty Years’ Experience. J. Am. Assoc. Gynecol. Laparosc. 2002, 9, 235–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granberg, S.; Gjelland, K.; Ekerhovd, E. The Management of Pelvic Abscess. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2009, 23, 667–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alauzet, C.; Mory, F.; Teyssier, C.; Hallage, H.; Carlier, J.P.; Grollier, G.; Lozniewski, A. Metronidazole Resistance in Prevotella Spp. and Description of a New Nim Gene in Prevotella Baroniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Veloo, A.C.M.; Chlebowicz, M.; Winter, H.L.J.; Bathoorn, D.; Rossen, J.W.A. Three Metronidazole-Resistant Prevotella Bivia Strains Harbour a Mobile Element, Encoding a Novel Nim Gene, nimK, and an Efflux Small MDR Transporter. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 2687–2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jennings, L.K.; Krywko, D.M. Pelvic Inflammatory Disease. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Perutelli, A.; Tascini, C.; Domenici, L.; Garibaldi, S.; Baroni, C.; Cecchi, E.; Salerno, M.G. Safety and Efficacy of Tigecycline in Complicated and Uncomplicated Pelvic Inflammatory Disease. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2018, 22, 3595–3601. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Total | p-Value | Post-Hoc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 46 | 27 | 34 | 107 | ||

| Age | 35.98 ± 11.61 | 43.96 ± 14.05 | 42.15 ± 15.44 | 39.95 ± 13.87 | 0.03 * | 1 < 2 |

| BMI | 25.25 ± 6.17 | 23.04 ± 4.43 | 25.05 ± 6.18 | 24.63 ± 5.81 | 0.26 | |

| Smoker (%) | 14 (30.4%) | 7 (25.9%) | 8 (23.5%) | 29 (27.1%) | 0.78 | |

| Ever pregnant (%) | 32 (69.6%) | 26 (96.3%) | 26 (76.5%) | 84 (78.5%) | 0.03 * | |

| Currently had IUD (%) | 9 (19.6%) | 3 (11.1%) | 2 (5.9%) | 14 (13.1%) | 0.20 | |

| Underlying disease (%) | 14 (30.4%) | 12 (44.4%) | 11 (32.4%) | 37 (34.6%) | 0.45 | |

| Days with VAS of pelvic pain ≥ 5 | 0.36 ± 0.71 | 0.26 ± 0.45 | 0.61 ± 1.12 | 0.41 ± 0.82 | 0.22 | |

| Days of BT > 38.3 °C | 0.11 ± 0.38 | 0.30 ± 0.54 | 0.58 ± 1.20 | 0.30 ± 0.79 | 0.03 * | 1 < 3 |

| WBC | 12,842.44 ± 4121.82 | 13,944.44 ± 4897.31 | 13,336.76 ± 4649.52 | 13,281.70 ± 4477.62 | 0.60 | |

| WBC > 10,600 (%) | 35 (77.8%) | 19 (70.4%) | 22 (64.7%) | 76 (71.7%) | 0.44 | |

| CRP | 7.13 ± 7.76 | 11.03 ± 8.76 | 8.94 ± 7.68 | 8.71 ± 8.07 | 0.17 | |

| Complications of TOA (%) | 1 (2.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (3.0%) | 2 (1.9%) | 1.00 | |

| Surgery during hospitalization (%) | 2 (4.3%) | 1 (3.7%) | 3 (8.8%) | 6 (5.6%) | 0.66 | |

| Readmission within 6 months (%) | 1 (2.2%) | 4 (14.8%) | 2 (5.9%) | 7 (6.5%) | 0.10 | |

| Length of stay | 4.78 ± 2.15 | 6.11 ± 2.31 | 6.76 ± 7.16 | 5.75 ± 4.47 | 0.13 | |

| Expenditures | 14,857.87 ± 9095.32 | 26,184.15 ± 23,164.93 | 33,078.88 ± 37,446.40 | 23,505.76 ± 25,825.62 | 0.005 * | 1 < 3 |

| Surgical Rate during Hospitalization | Readmission within 6 Months | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-Value | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| Age | 1.19 (1.02, 1.40) | 0.03 * | 0.94 (0.83, 1.07) | 0.38 |

| Group | - | - | - | - |

| Group 1 | 1.00 (Reference) | NA | 1.00 (Reference) | NA |

| Group 2 | 0.15 (0.00, 11.85) | 0.40 | 6.54 (0.30, 142.96) | 0.23 |

| Group 3 | 0.24 (0.01, 7.50) | 0.42 | 2.60 (0.09, 73.20) | 0.57 |

| Smoker (Yes vs. No) | 39.15 (0.36, 4227.59) | 0.13 | 0 (NA) | 1.00 |

| Ever pregnant (Yes vs. No) | 0.24 (0.00, 15.11) | 0.50 | 1.1 (0.04, 32.47) | 0.96 |

| IUD (Yes vs. No) | 0 (NA) | 1.00 | 0 (NA) | 1.00 |

| BMI | 1.12 (0.86, 1.45) | 0.41 | 1.07 (0.85, 1.34) | 0.57 |

| Has underlying disease (%) | 0.93 (0.12, 7.17) | 0.94 | 3.83 (0.45, 32.28) | 0.22 |

| Days of VAS of pelvic pain ≥ 5 | 2.96 (0.74, 11.76) | 0.12 | 4.50 (0.63, 32.16) | 0.13 |

| Days of BT > 38.3 °C | 4.50 (0.82, 24.71) | 0.08 | 0 (NA) | 1.00 |

| WBC (>10,600 vs. ≤10,600) | 0.23 (0.01, 5.99) | 0.37 | 8.84 (0.32, 247.14) | 0.20 |

| CRP | 0.97 (0.84, 1.11) | 0.64 | 0.77 (0.54, 1.09) | 0.14 |

| LOS | Expenditure | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (95% CI) | p-Value | β (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| Intercept | 0.82 (−4.12, 5.77) | 0.74 | −9560.63 (−38,256.47, 19,135.22) | 0.51 |

| Age | 0.12 (0.05, 0.19) | 0.001 * | 458.91 (41.64, 876.18) | 0.03 * |

| Group | - | - | - | - |

| Group1 | 1.00 (Reference) | NA | 1.00 (Reference) | NA |

| Group2 | 0.04 (−2.02, 2.10) | 0.98 | 4512.37 (−7440.75, 16,465.49) | 0.46 |

| Group3 | −0.25 (−2.18, 1.68) | 0.80 | 4979.54 (−6206.78, 16,165.86) | 0.38 |

| Smoker (Yes vs. No) | −1.07 (−3.06, 0.92) | 0.29 | 4622.40 (−6917.31, 16,162.11) | 0.43 |

| Ever pregnant (Yes vs. No) | −0.77 (−2.80, 1.25) | 0.45 | −3765.01 (−15,522.36, 7992.34) | 0.53 |

| IUD (Yes vs. No) | −0.76 (−3.05, 1.53) | 0.51 | −6210.64 (−19,520.41, 7099.13) | 0.36 |

| BMI | −0.10 (−0.24, 0.04) | 0.15 | 195.23 (−600.64, 991.11) | 0.63 |

| Underlying disease (Yes vs. No) | −0.35 (−1.62, 0.92) | 0.58 | 562.16 (−6804.65, 7928.98) | 0.88 |

| Days of VAS of pelvic pain ≥ 5 | 3.83 (2.76, 4.89) | <0.001 * | 4823.38 (−1339.23, 10,985.99) | 0.12 |

| Days of BT > 38.3 °C | 0.55 (−0.43, 1.53) | 0.27 | 18,276.24 (12,588.62, 23,963.85) | <0.001 * |

| WBC (>10,600 vs. ≤10,600) | −0.45 (−2.26, 1.36) | 0.62 | −7447.74 (−17,933.58, 3038.09) | 0.16 |

| CRP | −0.01 (−0.11, 0.10) | 0.91 | 289.68 (−321.27, 900.62) | 0.35 |

| Group 2 (n = 27) | Group 3 (n = 34) | |

|---|---|---|

| Antibiotic regimens | Clindamycin + Gentamicin + Metronidazole (n = 7) | Clindamycin + Gentamicin + Doxycycline (n = 2) |

| Ciprofloxacin + Metronidazole (n = 1) | Cefazolin (n = 4) | |

| Cefazolin + Gentamicin + Metronidazole (n = 12) | Imipenem (n = 2) | |

| Cefmetazole + Doxycycline + Metronidazole (n = 1) | Ceftazidime (n = 1) | |

| Ceftriaxone + Metronidazole (n = 2) | Cefmetazole (n = 1) | |

| Ceftriaxone + Doxycycline + Metronidazole (n = 3) | Imipenem + cefmetazole (n = 1) | |

| Flomoxef+ Metronidazole (n = 1) | Ertapenem (n = 3) | |

| Levofloxacin + (Sulfamethoxazole + Trimethoprim) (n = 2) | ||

| (Piperacillin + Tazobactam) + Doxycycline (n = 1) | ||

| Levofloxacin (n = 1) | ||

| Cefazolin + Gentamicin (n = 1) | ||

| Clindamycin + Doxycycline (n = 1) | ||

| Ampicillin + Levofloxacin (n = 2) | ||

| Flomoxef (n = 4) | ||

| Ampicillin + Levofloxacin (n = 1) | ||

| Amoxicillin + clavulanic acid (n = 1) | ||

| Meropenem (n = 1) | ||

| Levofloxacin+ Doxycycline (n = 1) | ||

| Cefepime (n = 1) | ||

| Ampicillin + Doxycycline (n = 2) | ||

| Moxifloxacin (n = 1) | ||

| Oxacillin + Clindamycin (n = 1) |

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Most common bacteria | Prevotella bivia (22.22%), Bacteroid fragilis (22.22%) | Bacteroid fragilis (25%) | Escherichia coli (35.29%) |

| Other bacteria | Escherichia coli (11.11%), Peptostreptococcus species (11.11%), Fusobacterium nucleatum, (11.11%), Fusobacterium necorphorum (11.11%), Cutibacterium acnes (11.11%) | Escherichia coli (12.5%), Enterobacter aerogenes (12.5%), Enterococcus faecalis (12.5%), Gardnerella vaginalis (12.5%), Peptostreptococcus anerobius (12.5%), Prevotella bivia (12.5%) | Enterococcus (11.76%), Prevotella bivia (11.76%), Streptococcus (11.76%), Bacteroid fragilis (5.88%), Klebsiella pneumoniae (5.88%), Peptostreptococcus species (5.88%), Proteus mirabilis (5.88%), Streptococcus sanguinis (5.88%) |

| Patients who had culture (%) | 17.39% | 33.33% | 55.88% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, L.-Y.; Harnod, T.; Chang, Y.-H.; Chen, H.; Ding, D.-C. The Combination of Clindamycin and Gentamicin Is Adequate for Pelvic Inflammatory Disease: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4145. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10184145

Chen L-Y, Harnod T, Chang Y-H, Chen H, Ding D-C. The Combination of Clindamycin and Gentamicin Is Adequate for Pelvic Inflammatory Disease: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2021; 10(18):4145. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10184145

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Li-Yeh, Tomor Harnod, Yu-Hsun Chang, Hsuan Chen, and Dah-Ching Ding. 2021. "The Combination of Clindamycin and Gentamicin Is Adequate for Pelvic Inflammatory Disease: A Retrospective Cohort Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 10, no. 18: 4145. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10184145

APA StyleChen, L.-Y., Harnod, T., Chang, Y.-H., Chen, H., & Ding, D.-C. (2021). The Combination of Clindamycin and Gentamicin Is Adequate for Pelvic Inflammatory Disease: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(18), 4145. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10184145