Patients’ Habits and the Role of Pharmacists and Telemedicine as Elements of a Modern Health Care System during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Ethical Approval

2.3. Description of the Questionnaire

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Population Characteristics

3.2. Patients Health

3.3. Telehealth

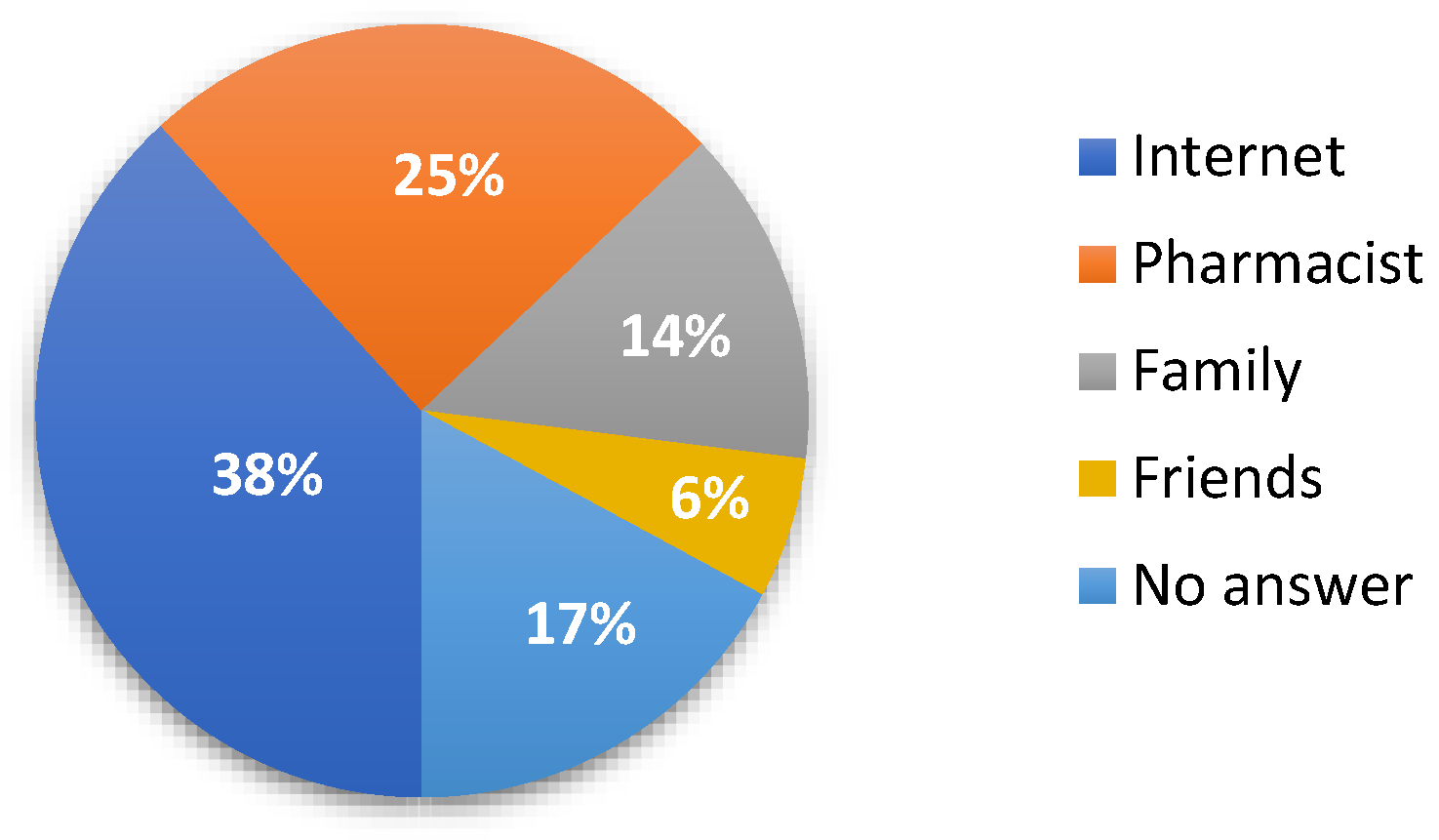

3.4. Access to Health Information and Pharmacist Advice

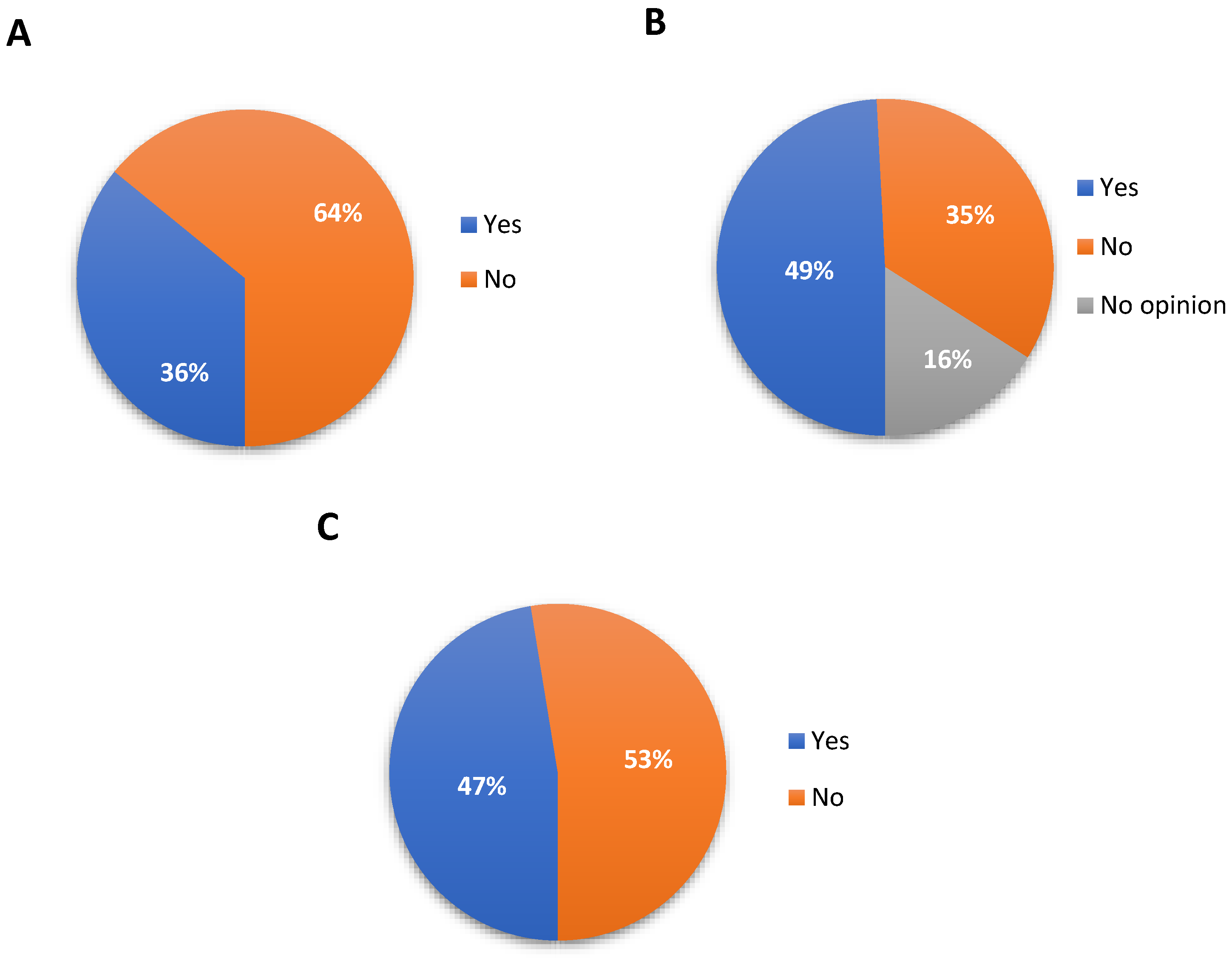

3.5. COVID-19 Vaccine

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- De Sio, S.; Buomprisco, G.; La Torre, G.; Lapteva, E.; Perri, R.; Greco, E.; Mucci, N.; Cedrone, F. The impact of COVID-19 on doctors’ well-being: Results of a web survey during the lockdown in Italy. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2020, 24, 7869–7879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidor, A.; Rzymski, P. Dietary Choices and Habits during COVID-19 Lockdown: Experience from Poland. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staszuk, A.; Wiatrak, B.; Tadeusiewicz, R.; Karuga-Kuźniewska, E.; Rybak, Z. Telerehabilitation approach for patients with hand impairment. Acta Bioeng. Biomech. 2016, 18, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Buliński, L.; Błachnio, A. Health in old age, and patients’ approaches to telemedicine in Poland. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2017, 24, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janusz, S. Telepathology in Poland, Present Status and Future Aspects. Electron. J. Pathol. Histol. 2000, 6, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Computerization in Healthcare. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/zdrowie/informatyzacja-w-ochronie-zdrowia (accessed on 9 June 2021).

- Pinto, G.S.; Hung, M.; Okoya, F.; Uzman, N. FIP’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic: Global pharmacy rises to the challenge. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2020, 17, 1929–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jęśkowiak, I.; Wiatrak, B.; Grosman-Dziewiszek, P.; Szeląg, A. The Incidence and Severity of Post-Vaccination Reactions after Vaccination against COVID-19. Vaccines 2021, 9, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Walkover, M.; Wu, Y.Y. The Challenge of COVID-19 for Adult Men and Women in the United States: Disparities of Psychological Distress by Gender and Age. Public Health 2021, 198, 218–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koenig, J.; Thayer, J.F. Sex differences in healthy human heart rate variability: A meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2016, 64, 288–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peine, A.; Paffenholz, P.; Martin, L.; Dohmen, S.; Marx, G.; Loosen, S.H. Telemedicine in Germany During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Multi-Professional National Survey. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e19745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ćwirlej-Sozańska, A.; Wilmowska-Pietruszyńska, A.; Sozański, B.; Wiśniowska-Szurlej, A. Analysis of Chronic Illnesses and Disability in a Community-Based Sample of Elderly People in South-Eastern Poland. Med. Sci. Monit. 2018, 24, 1387–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishimoto, M.; Ishikawa, T.; Odawara, M. Behavioral changes in patients with diabetes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Diabetol. Int. 2020, 12, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Consonni, M.; Telesca, A.; Grazzi, L.; Cazzato, D.; Lauria, G. Life with chronic pain during COVID-19 lockdown: The case of patients with small fibre neuropathy and chronic migraine. Neurol. Sci. 2020, 42, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eccleston, C.; Blyth, F.M.; Dear, B.; Fisher, E.A.; Keefe, F.J.; Lynch, M.E.; Palermo, T.M.; Reid, M.C.; Williams, A.C.D.C. Managing patients with chronic pain during the COVID-19 outbreak: Considerations for the rapid introduction of remotely supported (eHealth) pain management services. Pain 2020, 161, 889–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanaboni, P.; Fagerlund, A.J. Patients’ use and experiences with e-consultation and other digital health services with their general practitioner in Norway: Results from an online survey. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e034773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harnik, M.A.; Blättler, L.; Limacher, A.; Reisig, F.; Grosse Holtforth, M.; Streitberger, K. Telemedicine for chronic pain treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic: Do pain intensity and anxiousness correlate with patient acceptance? Pain Pract. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijesooriya, N.R.; Mishra, V.; Brand, P.L.; Rubin, B.K. COVID-19 and telehealth, education, and research adaptations. Paediatr. Respir. Rev. 2020, 35, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaswamy, A.; Yu, M.; Drangsholt, S.; Ng, E.; Culligan, P.J.; Schlegel, P.N.; Hu, J.C. Patient Satisfaction with Telemedicine During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Retrospective Cohort Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e20786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rademacher, N.J.; Cole, G.; Psoter, K.J.; Kelen, G.; Fan, J.W.Z.; Gordon, D.; Razzak, J. Use of Telemedicine to Screen Patients in the Emergency Department: Matched Cohort Study Evaluating Efficiency and Patient Safety of Telemedicine. JMIR Med. Inform. 2019, 7, e11233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, C.M.; Metzger, G.A.; Beane, J.D.; Dedhia, P.H.; Ejaz, A.; Pawlik, T.M. Telemedicine: Patient-Provider Clinical Engagement During the COVID-19 Pandemic and Beyond. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2020, 24, 1692–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patient Satisfaction Survey Report Who Use Teleparation from a Primary Doctor Health Care in the Period of COVID-19. 8 August 2020. Available online: https://www.nfz.gov.pl/download/gfx/nfz/pl/defaultaktualnosci/370/7788/1/raport_-_teleporady_u_lekarza_poz.pdf (accessed on 9 June 2021).

- Carico, R.; Sheppard, J.; Thomas, C.B. Community pharmacists and communication in the time of COVID-19: Applying the health belief model. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2020, 17, 1984–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giua, C.; Paoletti, G.; Minerba, L.; Malipiero, G.; Melone, G.; Heffler, E.; Pistone, A.; Keber, E.; Cimino, V.; Fimiani, G.; et al. Community pharmacist’s professional adaptation amid Covid-19 emergency: A national survey on Italian pharmacists. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2021, 43, 708–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cadogan, C.A.; Hughes, C.M. On the frontline against COVID-19: Community pharmacists’ contribution during a public health crisis. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2020, 17, 2032–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koster, E.S.; Philbert, D.; Bouvy, M.L. Impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on the provision of pharmaceutical care in community pharmacies. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2020, 17, 2002–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.-Q.; Yang, L.; Zhou, P.-X.; Li, H.-B.; Liu, F.; Zhao, R.-S.; Zheng, S.-Q.; Yang, L.; Zhou, P.-X.; Li, H.-B.; et al. Recommendations and guidance for providing pharmaceutical care services during COVID-19 pandemic: A China perspective. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2020, 17, 1819–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, J.; Christofferson, N.; Goodlet, K.J. Pharmacist-provided SARS-CoV-2 testing targeting a majority-Hispanic community during the early COVID-19 pandemic: Results of a patient perception survey. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzik, K.A.; Bethishou, L. The impact of COVID-19 on pharmacy transitions of care services. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2020, 17, 1908–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lussier, M.E.; Evans, H.J.; Wright, E.; Gionfriddo, M.R. The impact of community pharmacist involvement on transitions of care: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2020, 60, 153–162.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Merks, P.; Jakubowska, M.; Drelich, E.; Świeczkowski, D.; Bogusz, J.; Bilmin, K.; Sola, K.F.; May, A.; Majchrowska, A.; Koziol, M.; et al. The legal extension of the role of pharmacists in light of the COVID-19 global pandemic. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2020, 17, 1807–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Show Pharmacist Your E-Prescriptions. Available online: https://pacjent.gov.pl/aktualnosc/pokaz-farmaceucie-swoje-e-recepty (accessed on 18 June 2021).

- REPORT: Pharmaceutical Care. Comprehensive Analysis, the Implementation Process. Available online: https://www.nia.org.pl/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/RAPORT_OPIEKA_FARMACEUTYCZNA.pdf (accessed on 9 June 2021).

- Hindi, A.M.K.; Schafheutle, E.; Jacobs, S. Patient and public perspectives of community pharmacies in the United Kingdom: A systematic review. Health Expect. 2017, 21, 409–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Quteimat, O.M.; Amer, A.M. SARS-CoV-2 outbreak: How can pharmacists help? Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2020, 17, 480–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Munshi, K.D.; Hong, S.H. Racial and ethnic disparities in influenza vaccinations among community pharmacy patients and non-community pharmacy respondents. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2013, 10, 126–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aruru, M.; Truong, H.-A.; Clark, S. Pharmacy Emergency Preparedness and Response (PEPR): A proposed framework for expanding pharmacy professionals’ roles and contributions to emergency preparedness and response during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2020, 17, 1967–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czech, M.; Balcerzak, M.; Antczak, A.; Byliniak, M.; Piotrowska-Rutkowska, E.; Drozd, M.; Juszczyk, G.; Religioni, U.; Vaillancourt, R.; Merks, P. Flu Vaccinations in Pharmacies—A Review of Pharmacists Fighting Pandemics and Infectious Diseases. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Number of Pharmacists Who Can Vaccinate Patients against COVID-19 Is Growing. 24 May 2021. Available online: Nia.org.pl (accessed on 18 June 2021).

- Babicki, M.; Mastalerz-Migas, A. Attitudes toward Vaccination against COVID-19 in Poland. A Longitudinal Study Performed before and Two Months after the Commencement of the Population Vaccination Programme in Poland. Vaccines 2021, 9, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Huidobro, D.; Rivera, S.; Chang, S.V.; Bravo, P.; Capurro, D. System-Wide Accelerated Implementation of Telemedicine in Response to COVID-19: Mixed Methods Evaluation. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e22146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Grosman-Dziewiszek, P.; Wiatrak, B.; Jęśkowiak, I.; Szeląg, A. Patients’ Habits and the Role of Pharmacists and Telemedicine as Elements of a Modern Health Care System during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4211. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10184211

Grosman-Dziewiszek P, Wiatrak B, Jęśkowiak I, Szeląg A. Patients’ Habits and the Role of Pharmacists and Telemedicine as Elements of a Modern Health Care System during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2021; 10(18):4211. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10184211

Chicago/Turabian StyleGrosman-Dziewiszek, Patrycja, Benita Wiatrak, Izabela Jęśkowiak, and Adam Szeląg. 2021. "Patients’ Habits and the Role of Pharmacists and Telemedicine as Elements of a Modern Health Care System during the COVID-19 Pandemic" Journal of Clinical Medicine 10, no. 18: 4211. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10184211

APA StyleGrosman-Dziewiszek, P., Wiatrak, B., Jęśkowiak, I., & Szeląg, A. (2021). Patients’ Habits and the Role of Pharmacists and Telemedicine as Elements of a Modern Health Care System during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(18), 4211. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10184211