Self-Injuries and Their Functions with Respect to Suicide Risk in Adolescents with Conduct Disorder: Findings from a Path Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedures

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. The MINI-KID

2.3.2. NSSIs-Interview

- -

- “Yes” to question 1 and “No” to question number 2.

- -

- At least one of the following: cutting, burning, picking, hitting and/or excessive rubbing indicated as the answer to question number 3.

- -

- One of the following answers to question number 5 (in subsection statements): to alleviate anxiety/sadness/tension, to manage bad feelings, to punish or control somebody, to get someone’s attention, to punish yourself and/or to feel better.

2.3.3. The Inventory of Statements about Self-Injury (ISAS)

2.3.4. The Eysenck’s Impulsivity Inventory (IVE)

2.3.5. The Children Depression Scale (CDI-2:S)

2.3.6. The Spielberg State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI)

2.3.7. The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (SES)

2.3.8. The Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire (BPAQ)

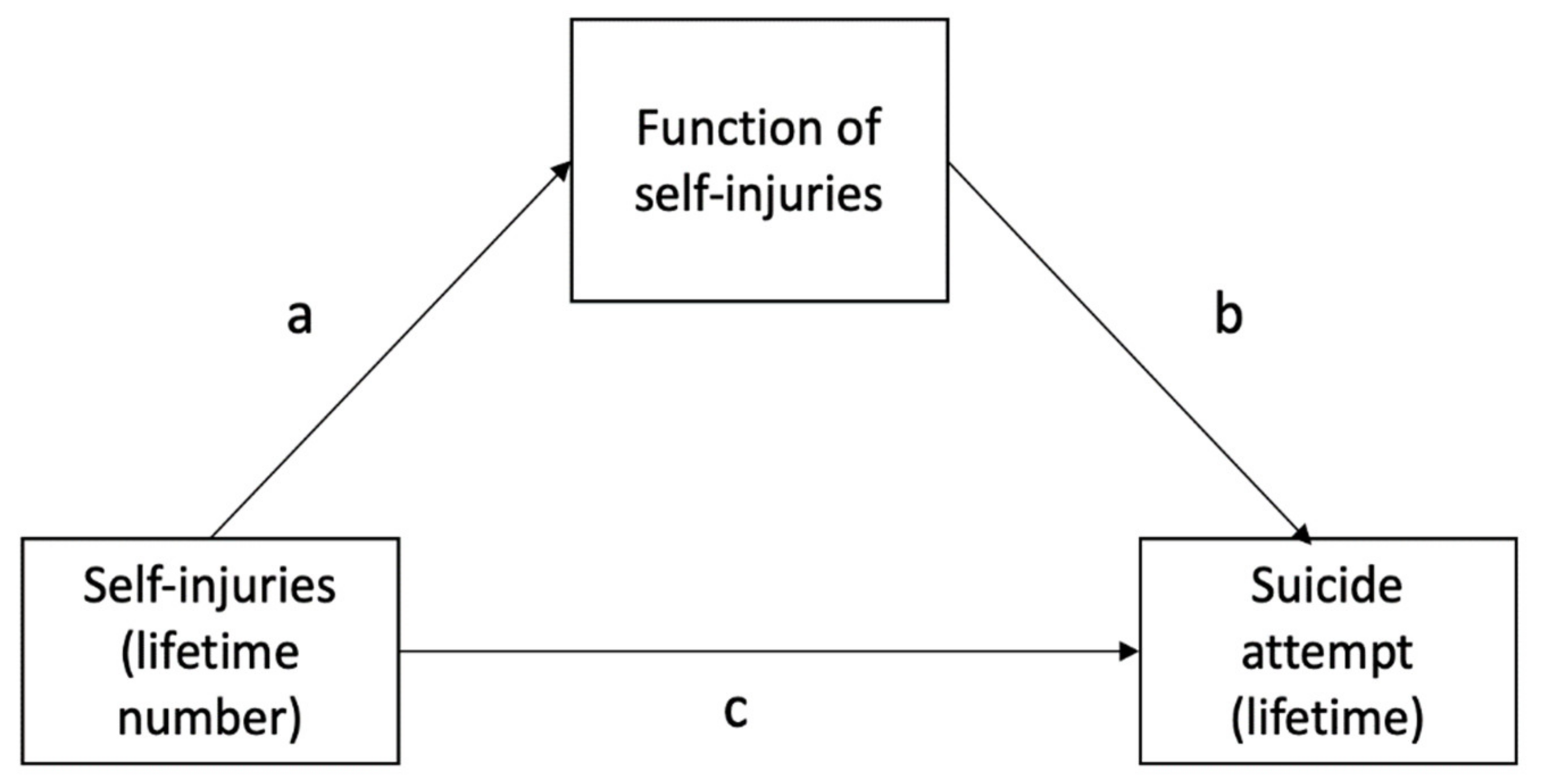

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Question | YES | NO | N/A | Comments: |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Have you ever deliberately injured yourself? | ||||

| 2. Were you having any suicidal intention when you were doing this? | ||||

| 3. What methods have you used to harm yourself? | ||||

| 4. For what reasons have you injured yourself? | ||||

| 5. For what purpose have you injured yourself? | ||||

| to alleviate anxiety/sadness/tension | ||||

| to manage bad feelings | ||||

| to punish or control somebody | ||||

| to get someone’s attention | ||||

| to punish yourself | ||||

| to feel better | ||||

| 6. How old were you when you engaged in this behaviour for the first time? | ||||

| 7. How many times have you done this since you started? | ||||

| 8. Have you harmed yourself during the last year? | ||||

| 9. How many days did you injure yourself last year?/last month?/last week? | ||||

| 10. When did you injure yourself last time? | ||||

References

- Brausch, A.M.; Muehlenkamp, J.J. Perceived effectiveness of NSSI in achieving functions on severity and suicide risk. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 265, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellvi Obiols, P.; Lucas Romero, E.; Miranda-Mendizábal, A.; Parés Badell, O.; Almenara, J.; Alonso, I.; Blasco Cubedo, M.J.; Gabilondo Cuéllar, A.; Gili, M.; Lagares, C.; et al. Longitudinal association between self-injurious thoughts and behaviors and suicidal behavior in adolescents and young adults: A systematic review with meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 215, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Groschwitz, R.C.; Kaess, M.; Fischer, G.; Ameis, N.; Schulze, U.M.; Brunner, R.; Koelch, M.; Plener, P.L. The association of non-suicidal self-injury and suicidal behavior according to DSM-5 in adolescent psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatry Res. 2015, 228, 454–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nock, M.K.; Borges, G.; Bromet, E.J.; Alonso, J.; Angermeyer, M.; Beautrais, A.; Bruffaerts, R.; Chiu, W.T.; De Girolamo, G.; Gluzman, S.; et al. Cross-national prevalence and risk factors for suicidal ideation, plans, and attempts. Br. J. Psychiatry 2008, 192, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szewczuk-Bogusławska, M.; Kaczmarek-Fojtar, M.; Adamska, A.; Frydecka, D.; Misiak, B. Assessment of the association between non-suicidal self-injury disorder and suicidal behaviour disorder in females with conduct disorder. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muehlenkamp, J.J.; Claes, L.; Havertape, L.; Plener, P.L. International prevalence of adolescent non-suicidal self-injury and deliberate self-harm. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2012, 6, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Orri, M.; Scardera, S.; Perret, L.C.; Bolanis, D.; Temcheff, C.; Séguin, J.R.; Boivin, M.; Turecki, G.; Tremblay, R.E.; Côté, S.M.; et al. Mental health problems and risk of suicidal ideation and attempts in adolescents. Pediatrics 2020, 1, e20193823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andover, M.S.; Primack, J.M.; Gibb, B.E.; Pepper, C.M. An Examination of Non-Suicidal Self-Injury in Men: Do Men Differ From Women in Basic NSSI Characteristics? Arch. Suicide Res. 2010, 14, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nock, M.K.; Joiner, T.E.; Gordon, K.H.; Lloyd-Richardson, E.; Prinstein, M.J. Non-suicidal self-injury among adolescents: Diagnostic correlates and relation to suicide attempts. Psychiatry Res. 2006, 144, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, B.J.; Layden, B.K.; Butler, S.M.; Chapman, A.L. How often, or how many ways: Clarifying the relationship between non-suicidal self-injury and suicidality. Arch. Suicide Res. 2013, 17, 397–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knorr, A.C.; Ammerman, B.A.; Hamilton, A.J.; McCloskey, M.S. Predicting status along the continuum of suicidal thoughts and behavior among those with a history of nonsuicidal self-injury. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 273, 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P.J.; Jomar, K.; Dhingra, K.; Forrester, R.; Shahmalak, U.; Dickson, J.M. A meta-analysis of the prevalence of different functions of non-suicidal self-injury. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 227, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suyemoto, K.L. The functions of self-mutilation. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 1998, 18, 531–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, T.A.; Jacobucci, R.; Ammerman, B.A.; Piccirillo, M.; McCloskey, M.S.; Heimberg, R.G.; Alloy, L.B. Identifying the relative importance of non-suicidal self-injury features in classifying suicidal ideation, plans, and behavior using exploratory data mining. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 262, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, K.; Garisch, J.A.; Wilson, M.S. Nonsuicidal self-injury thoughts and behavioural characteristics: Associations with suicidal thoughts and behaviours among community adolescents. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 1, 1247–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, E.; Tsypes, A.; Eidlitz, L.; Ernhout, C.; Whitlock, J. Frequency and functions of non-suicidal self-injury: Associations with suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Psychiatry Res. 2015, 28, 225–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association Publishing: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus, L.; Schmid, M.; In-Albon, T. Anti-Suicide Function of Nonsuicidal Self-Injury in Female Inpatient Adolescents. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fliege, H.; Lee, J.; Grimm, A.; Klapp, B.F. Risk factors and correlates of deliberate self-harm behavior: A systematic review. J. Psychosom. Res. 2009, 66, 477–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaess, M.; Parzer, P.; Mattern, M.; Plener, P.L.; Bifulco, A.; Resch, F.; Brunner, R. Adverse childhood experiences and their impact on frequency, severity, and the individual function of nonsuicidal self-injury in youth. Psychiatry Res. 2013, 206, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mars, B.; Heron, J.; Crane, C.; Hawton, K.; Kidger, J.; Lewis, G.; Gunnell, D. Differences in risk factors for self-harm with and without suicidal intent: Findings from the ALSPAC cohort. J. Affect. Disord. 2014, 168, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Murray, J.; Farrington, D.P. Risk factors for conduct disorder and delinquency: Key findings from longitudinal studies. Can. J. Psychiatry 2010, 55, 633–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sheehan David, V.; Sheehan Kathy, H.; Shytle, R.D.; Janavs Juris, B.Y.; Rogers Jamison, E.; Milo Karen MStock Saundra, L. Reliability and Validity of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children and Adolescents (MINI-KID). J. Clin. Psychiatry 2010, 7, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamowska, S.; Adamowski, T.; Frydecka, D.; Kiejna, A. Diagnostic validity Polish language version of the questionnaire MINI-KID (Mini International Neuropsychiatry Interview for Children and Adolescent). Compr. Psychiatry 2014, 55, 1744–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klonsky, E.D.; Glenn, C.R. Assessing the functions of non-suicidal self-injury: Psychometric properties of the Inventory of Statements About Self-injury (ISAS). J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2009, 31, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubiak, A. Mechanizm Radzenia Sobie z Napięciem u osób Podejmujących Nawykowe Samouszkodzenia. Praca doktorska.: Uniwersytet im Adama Mickiewicza, Poznań. 2014. Available online: https://repozytorium.amu.edu.pl/jspui/bitstream/10593/10493/3/Anna%20Kubiak__rozprawa%20doktorska.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Eysenck, S.B.G.; Eysenck, H.J. Impulsiveness and venturesomeness: Their position in a dimensional system of personality description. Psychol. Rep. 1978, 43, 1247–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovacs, M. CDI 2 Zestaw Kwestionariuszy do Diagnozy Depresji u Dzieci i Młodzieży; Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych Polskiego Towarzystwa Psychologicznego: Warszawa, Poland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger, C.D.; Gorsuch, R.L.; Lushene, R.E. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Buss, A.H.; Perry, M. The Aggression Questionnaire. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 63, 452–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis. A Regression-Based Approach; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, J.D.; Gómez, J.M. The Relationship of Psychological Trauma and Dissociative and Posttraumatic Stress Disorders to Nonsuicidal Self-Injury and Suicidality: A Review. J. Trauma Dissociation 2015, 16, 232–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calati, R.; Benssi, I.; Courtet, P. The link between dissociation and both suicide attempts and non-suicidal self-injury: Meta-analyses. Psychiatry Res. 2017, 251, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Suicide Attempt (+), n = 37 | Suicide Attempt (–), n = 40 | Statistics | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 14.7 ± 1.1 | 14.6 ± 1.1 | U = 789.5, p = 0.601 |

| Sex, F/M (%) | 31/6 | 26/14 | χ2 = 3.527, p = 0.060 |

| Age of self-harm onset, years | 10.4 ± 4.5 | 10.9 ± 4.3 | U = 568.5, p = 0.469 |

| Recent year number of self-injuries | 37.6 ± 67.0 | 33.9 ± 87.9 | U = 768.5, p = 0.048 |

| Lifetime number of self-injuries | 214.0 ± 408.4 | 151.4 ± 320.6 | U = 681.5, p = 0.702 |

| CDI2—depression | 24.6 ± 14.7 | 17.7 ± 11.5 | t = 1.385, p = 0.178 |

| STAI—trait anxiety | 51.0 ± 7.9 | 43.5 ± 16.1 | t = 2.521, p = 0.014 |

| STAI—state anxiety | 55.1 ± 9.9 | 46.0 ± 13.7 | t = 3.237, p = 0.002 |

| SES—self-esteem | 21.2 ± 6.2 | 26.3 ± 5.6 | t = −3.729, p < 0.001 |

| BPAQ—physical aggression | 19.3 ± 7.3 | 19.7 ± 7.0 | t = −0.215, p = 0.830 |

| BPAQ—verbal aggression | 13.5 ± 5.9 | 14.1 ± 4.8 | t = −0.495, p = 0.622 |

| BPAQ—anger | 18.6 ± 6.0 | 18.3 ± 6.7 | t = 0.201, p = 0.842 |

| BPAQ—hostility | 18.7 ± 8.7 | 19.4 ± 7.7 | t = −0.387, p = 0.700 |

| IVE—adventuresomeness | 8.5 ± 3.4 | 9.2 ± 3.4 | U = 503.5, p = 0.269 |

| IVE — empathy | 12.3 ± 3.0 | 12.4 ± 3.7 | t = −0.155, p = 0.878 |

| IVE—impulsivity | 10.3 ± 4.7 | 11.2 ± 3.4 | t = −0.977, p = 0.332 |

| Affect regulation | 3.5 ± 1.7 | 2.8 ± 1.9 | t = 1.658, p = 0.102 |

| Interpersonal boundaries | 1.7 ± 1.5 | 1.6 ± 1.6 | U = 564.5, p = 0.612 |

| Self-punishment | 3.3 ± 2.2 | 2.3 ± 2.0 | U = 670.0, p = 0.056 |

| Self-care | 2.0 ± 1.6 | 1.5 ± 1.7 | U = 696.5, p = 0.128 |

| Anti-dissociation feeling generation | 2.7 ± 1.9 | 1.7 ± 1.9 | U = 750.0, p = 0.030 |

| Anti-suicide | 2.9 ± 1.7 | 1.7 ± 1.6 | U = 794.0, p = 0.007 |

| Sensation seeking | 1.2 ± 1.1 | 1.5 ± 1.5 | U = 540.0, p = 0.646 |

| Peer bonding | 1.0 ± 1.4 | 1.7 ± 1.9 | U = 479.5, p = 0.203 |

| Interpersonal influence | 1.8 ± 1.7 | 1.6 ± 1.6 | U = 0.620, p = 0.578 |

| Toughness | 2.5 ± 1.7 | 1.7 ± 1.8 | U = 721.0, p = 0.070 |

| Marking distress | 1.2 ± 1.6 | 1.1 ± 1.3 | U = 584.0, p = 0.914 |

| Revenge | 1.4 ± 1.6 | 1.6 ± 1.7 | U = 541.0, p = 0.656 |

| Autonomy | 1.6 ± 1.6 | 1.5 ± 1.7 | U = 597.0, p = 0.790 |

| Affect regulation | r = 0.551, p < 0.001 |

| Interpersonal boundaries | r = 0.129, p = 0.301 |

| Self-punishment | r = 0.501, p < 0.001 |

| Self-care | r = 0.495, p < 0.001 |

| Anti-dissociation feeling generation | r = 0.474, p < 0.001 |

| Anti-suicide | r = 0.495, p < 0.001 |

| Sensation seeking | r = 0.042, p = 0.732 |

| Peer bonding | r = −0.082, p = 0.501 |

| Interpersonal influence | r = 0.154, p = 0.206 |

| Toughness | r = 0.418, p < 0.001 |

| Marking distress | r = 0.030, p = 0.809 |

| Revenge | r = 0.195, p = 0.108 |

| Autonomy | r = 0.210, p = 0.083 |

| Mediator | Effect | Statistics |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-dissociation feeling generation | Effect of lifetime number of NSSIs on mediator (a) | B = 0.0012, SE = 0.006, 95%CI = 0.0001–0.0024 |

| Effect of mediator on lifetime history of suicide attempts (b) | B = 0.2591, SE = 0.1383, 95%CI = −0.0119–0.5300 | |

| Direct effect of lifetime number of NSSIs on lifetime history of suicide attempts (c) | B = 0.002, SE = 0.007, 95%CI = −0.0012–0.0015 | |

| Indirect effect of lifetime number of NSSIs on lifetime history of suicide attempts (through mediator) | B = 0.0003, SE = 0.0005, 95%CI = 0.001–0.0018 | |

| Anti-suicide | Effect of lifetime number of NSSIs on mediator (a) | B = 0.0056, SE = 0.0027, 95%CI = 0.0002–0.0110 |

| Effect of mediator on lifetime history of suicide attempts (b) | B = 0.425, SE = 0.1646, 95%CI = 0.1024–0.7477 | |

| Direct effect of lifetime number of NSSIs on lifetime history of suicide attempts (c) | B = 0.0024, SE = 0.0034, 95%CI = −0.0083–0.0048 | |

| Indirect effect of lifetime number of NSSIs on lifetime history of suicide attempts (through mediator) | B = 0.0023, SE = 0.0028, 95%CI = 0.002–0.0108 |

| Mediator | Effect | Statistics |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-dissociation feeling generation | Effect of lifetime number of NSSIs on mediator (a) | B = 0.0266, SE = 0.0091, 95%CI = 0.0081–0.0450 |

| Effect of mediator on lifetime history of suicide attempts (b) | B = 0.4872, SE = 0.2115, 95%CI = 0.0726–0.9018 | |

| Direct effect of lifetime number of NSSIs on lifetime history of suicide attempts (c) | B = −0.0133, SE = 0.0138, 95%CI = −0.0403–0.0137 | |

| Indirect effect of lifetime number of NSSIs on lifetime history of suicide attempts (through mediator) | B = 0.0129, SE = 0.0105, 95%CI = 0.0024–0.0435 | |

| Anti-suicide | Effect of lifetime number of NSSIs on mediator (a) | B = 0.0249, SE = 0.0085, 95%CI = 0.0078–0.0421 |

| Effect of mediator on lifetime history of suicide attempts (b) | B = 0.6163, SE = 0.2423, 95%CI = 0.1415–1.0911 | |

| Direct effect of lifetime number of NSSIs on lifetime history of suicide attempts (c) | B = −0.0166, SE = 0.0148, 95%CI = −0.0456–0.0124 | |

| Indirect effect of lifetime number of NSSIs on lifetime history of suicide attempts (through mediator) | B = 0.0154, SE = 0.0114, 95%CI = 0.0030–0.0475 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Szewczuk-Bogusławska, M.; Kaczmarek-Fojtar, M.; Halicka-Masłowska, J.; Misiak, B. Self-Injuries and Their Functions with Respect to Suicide Risk in Adolescents with Conduct Disorder: Findings from a Path Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4602. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10194602

Szewczuk-Bogusławska M, Kaczmarek-Fojtar M, Halicka-Masłowska J, Misiak B. Self-Injuries and Their Functions with Respect to Suicide Risk in Adolescents with Conduct Disorder: Findings from a Path Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2021; 10(19):4602. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10194602

Chicago/Turabian StyleSzewczuk-Bogusławska, Monika, Małgorzata Kaczmarek-Fojtar, Joanna Halicka-Masłowska, and Błażej Misiak. 2021. "Self-Injuries and Their Functions with Respect to Suicide Risk in Adolescents with Conduct Disorder: Findings from a Path Analysis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 10, no. 19: 4602. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10194602

APA StyleSzewczuk-Bogusławska, M., Kaczmarek-Fojtar, M., Halicka-Masłowska, J., & Misiak, B. (2021). Self-Injuries and Their Functions with Respect to Suicide Risk in Adolescents with Conduct Disorder: Findings from a Path Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(19), 4602. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10194602