Adherence to and the Maintenance of Self-Management Behaviour in Older People with Musculoskeletal Pain—A Scoping Review and Theoretical Models

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials & Methods

2.1. Methods, First Aim

2.1.1. Eligibility Criteria

- manage symptoms;

- manage treatment;

- manage physical and psychosocial consequences;

- manage lifestyle changes regarding living with chronic conditions;

- monitor the condition;

- affect cognitive, behavioural and emotional responses.

2.1.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.1.3. Selection of Sources of Evidence

2.1.4. Data Charting Process and Parameters

2.1.5. Synthesis of Results

2.2. Methods, Second Aim

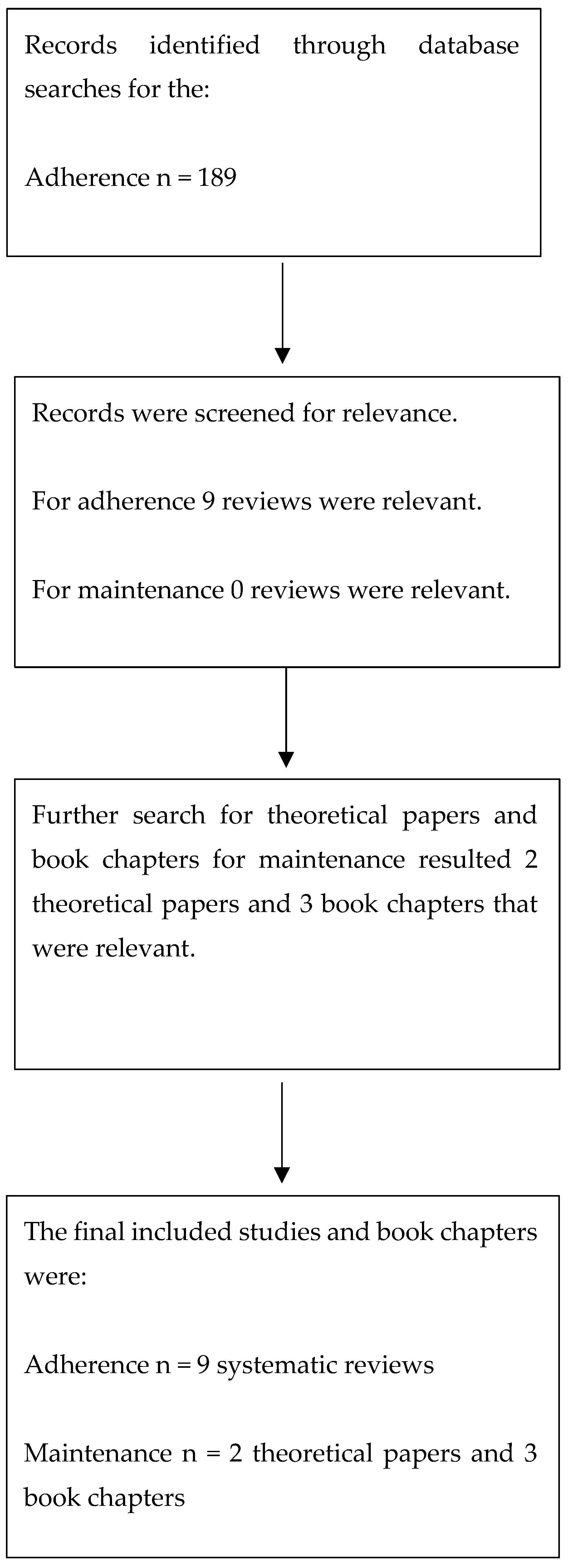

2.2.1. Eligibility Criteria, Information Sources and Search Strategy for the Theoretical Models for Adherence to and Maintenance of Behavioural Change

- exercise, adherence, pain, systematic review = 71 hits;

- physical activity, adherence, pain, systematic review = 76 hits;

- exercise, adherence, chronic pain, systematic review = 19 hits;

- physical activity, adherence, chronic pain, systematic review = 23 hits.

- exercise, maintenance, pain, systematic review = 8 hits;

- physical activity, maintenance, pain, systematic review = 13 hits;

- exercise, maintenance, chronic pain, systematic review = 4 hits;

- physical activity, maintenance, chronic pain, systematic review = 4 hits.

2.2.2. Synthesis of Results

3. Results

3.1. The First Aim

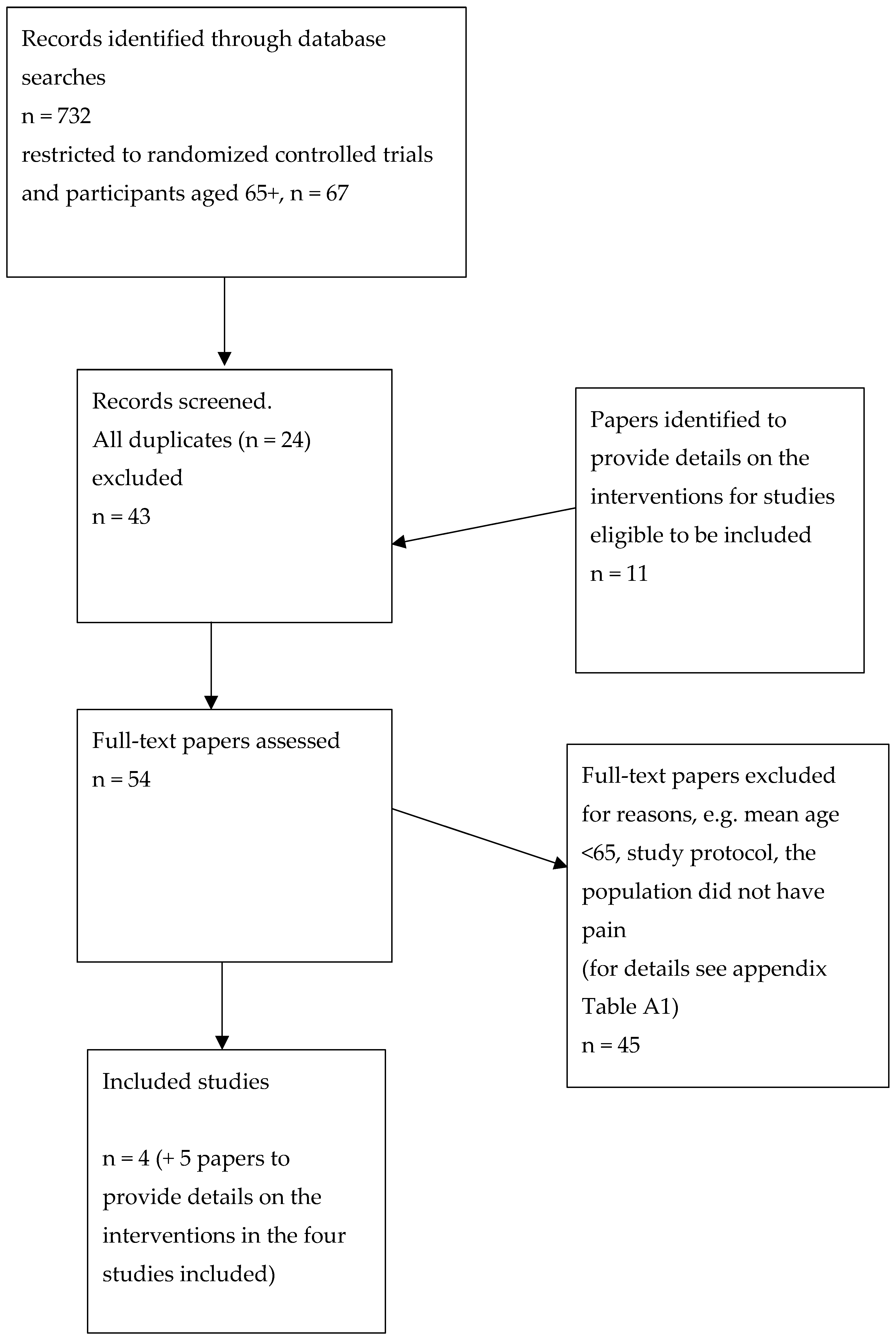

3.1.1. Selection of Sources of Evidence

3.1.2. Characteristics and Results of the Individual Sources of Evidence

3.2. The Second Aim

3.2.1. Selection of Sources of Evidence

3.2.2. Characteristics and Results of Individual Sources of Evidence

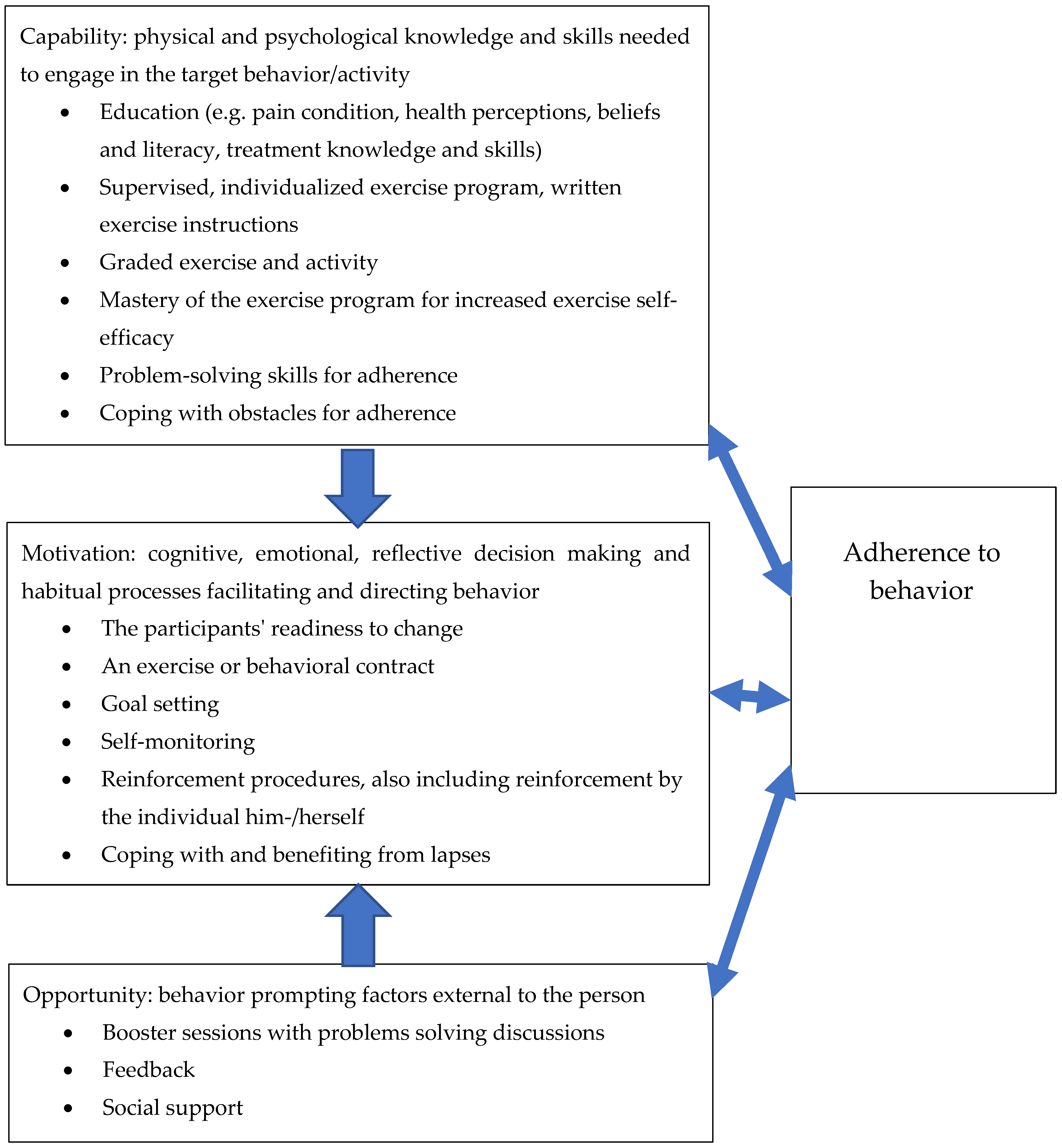

3.3. Synthesis of the Results Regarding Aims One and Two

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Evidence

4.2. Limitations and Strengths

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Reference | Reasons for Excluding the Study |

|---|---|

| Ang et al. 2011 and 2013 [46,47] | The mean age of the study population was 46 years |

| Aragonés et al. [48] | The mean age of the study population was 48 years |

| Beissner et al. [49] | Adherence of physiotherapists to the treatment regime was studied. |

| Bennell et al. [50] | The mean age of the study population was approximately 62 years |

| Bennell et al. [51] | The study protocol was inappropriate |

| Bennell et al. [52] | The mean age of the study population was 62 years |

| Bourgault et al. [53] | The mean age of the study population was approximately 48 years |

| Bove et al. [54] | The study was a qualitative study based on an RCT that has not been published yet |

| Brady et al. 2017 and 2018 [55,56] | The study from 2017 was a study protocol The mean age of the study population was 55 years |

| Cooke et al. [57] | A pain-related self-management intervention was not included |

| Dziedzic et al. 2014 and 2018 [58,59] | The study protocol was inappropriate * Did not fulfil the self-management programme definition: two scores of yes (2 and 4), two scores of partly (1 and 3), and two scores of no (5 and 6) |

| Kennedy et al. [60] | Kennedy et al. did not target populations with pain |

| Edbrooke et al. [61] | Cancer population |

| Elander et al. [62] | The mean age of the study population was 50 years |

| Geraghty et al. [63] | The mean age of the study population was 57 years |

| Gustavsson et al. [64] | The mean age of the study population was 46 years |

| Hinman et al. [65] | The study protocol was inappropriate |

| Jahn et al. [66] | Cancer population |

| Jernelöv et al. [67] | The intervention targeted insomnia not pain-related health problems |

| Kahan et al. [68] | The study protocol was inappropriate |

| Li et al. [69] | * Did not fulfil the self-management programme definition: one score of yes (2), one score of partly (3), and four scores of no (1, 4, 5 and 6) |

| Littlewood et al. [70] | The mean age of the study population was 63 years |

| Lonsdale et al. [71] | The mean age of the study population was 45 years |

| Low et al. [72] | The mean age of the study population was approximately 50 years |

| Mars et al. and Taylor et al. [73,74] | The mean age of the study population was 60 years |

| Matthias et al. [75] | The mean age of the study population was 57 years |

| McCusker et al. [76] | The intervention targeted depression not pain-related health problems |

| Mehlsen et al. and Frostholm et al. [77,78] | The mean age of the study population was 54 years |

| Mestre et al. [79] | Cancer population, lymphedema |

| Nevedal et al. [80] | The mean age of the study population was 56 years |

| Oesch et al. [81] | * Did not fulfil the self-management programme definition: two scores of yes (1 and 2), two scores of partly (3 and 5), and two scores of no (4 and 6) |

| Reed et al. [82] | The participants’ age was categorized, and the mean was not reported. About half of the study population was aged 60–75 years. No measures of adherence to the self-management programme were included. |

| Saner et al. 2015 and 2018 [83,84] | Qualitative study; an RCT exists, but the mean age of the study population was 41 years |

| Smith et al. [85] | The study protocol was inappropriate |

| Smith et al. [86] | The mean age of the study population was 29 years |

| Suman et al. [87] | The study protocol was inappropriate |

| Xiao et al. [88] | The study population had cardiovascular health problems |

| Zadro et al. [89] | * Did not fulfil the self-management programme definition: one score of yes (2), two scores of partly (3 and 5), and three scores of no (1, 4, and 6) |

| Zgierska et al. [90] | The mean age of the study population was 52 years |

References

- WHO. Adherence to Long Term Therapies, Evidence for Action; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hayden, J.A.; van Tulder, M.W.; Tomlinson, G. Systematic review: Strategies for using exercise therapy to improve outcomes in chronic low back pain. Ann. Intern. Med. 2005, 142, 776–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakobsen, M.D.; Sundstrup, E.; Brandt, M.; Andersen, L.L. Factors affecting pain relief in response to physical exercise interventions among healthcare workers. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2017, 27, 1854–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Gool, C.H.; Penninx, B.W.; Kempen, G.I.; Rejeski, W.J.; Miller, G.D.; van Eijk, J.T.; Pahor, M.; Messier, S.P. Effects of exercise adherence on physical function among overweight older adults with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2005, 53, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, J.M.; Brennan, S.F.; French, D.P.; Patterson, C.C.; Kee, F.; Hunter, R.F. Mediators of Behavior Change Maintenance in Physical Activity Interventions for Young and Middle-Aged Adults: A Systematic Review. Ann. Behav. Med. 2018, 52, 513–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Amireault, S.; Godin, G.; Vézina-Im, L.-A. Determinants of physical activity maintenance: A systematic review and meta-analyses. Health Psychol. Rev. 2013, 7, 55–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, J.; Wright, C.; Sheasby, J.; Turner, A.; Hainsworth, J. Self-management approaches for people with chronic conditions: A review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2002, 48, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Yuan, C.; Xiao, X.; Chu, J.; Qiu, Y.; Qian, H. Self-management programs for chronic musculoskeletal pain conditions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Patient Educ. Couns. 2011, 85, e299–e310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keogh, A.; Tully, M.A.; Matthews, J.; Hurley, D.A. A review of behaviour change theories and techniques used in group based self-management programmes for chronic low back pain and arthritis. Man. Ther. 2015, 20, 727–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisele, A.; Schagg, D.; Krämer, L.V.; Bengel, J.; Göhner, W. Behaviour change techniques applied in interventions to enhance physical activity adherence in patients with chronic musculoskeletal conditions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Patient Educ. Couns. 2019, 102, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devos-Comby, L.; Cronan, T.; Roesch, S.C. Do exercise and self-management interventions benefit patients with osteoarthritis of the knee? A metaanalytic review. J. Rheumatol. 2006, 33, 744–756. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ersek, M.; Turner, J.A.; McCurry, S.M.; Gibbons, L.; Kraybill, B.M. Efficacy of a self-management group intervention for elderly persons with chronic pain. Clin. J. Pain. 2003, 19, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, M.C.; Papaleontiou, M.; Ong, A.; Breckman, R.; Wethington, E.; Pillemer, K. Self-management strategies to reduce pain and improve function among older adults in community settings: A review of the evidence. Pain. Med. 2008, 9, 409–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colquhoun, H.L.; Levac, D.; O’Brien, K.K.; Straus, S.; Tricco, A.C.; Perrier, L.; Kastner, M.; Moher, D. Scoping reviews: Time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2014, 67, 1291–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.; Colquhoun, H.; Kastner, M.; Levac, D.; Ng, C.; Sharpe, J.P.; Wilson, K.; et al. A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2016, 16, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- OSF Registry. Available online: https://osf.io/muzf9 (accessed on 14 January 2021).

- Beinart, N.A.; Goodchild, C.E.; Weinman, J.A.; Ayis, S.; Godfrey, E.L. Individual and intervention-related factors associated with adherence to home exercise in chronic low back pain: A systematic review. Spine J. 2013, 13, 1940–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzat, A.M.; MacPherson, K.; Leese, J.; Li, L.C. The effects of interventions to increase exercise adherence in people with arthritis: A systematic review. Musculoskelet. Car. 2015, 13, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, J.L.; Holden, M.A.; Mason, E.E.; Foster, N.E. Interventions to improve adherence to exercise for chronic musculoskeletal pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010, 2010, Cd005956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, S.M.; Burton, M.; Bradley, L.; Littlewood, C. Interventions for enhancing adherence with physiotherapy: A systematic review. Man. Ther. 2010, 15, 514–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meade, L.B.; Bearne, L.M.; Sweeney, L.H.; Alageel, S.H.; Godfrey, E.L. Behaviour change techniques associated with adherence to prescribed exercise in patients with persistent musculoskeletal pain: Systematic review. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2019, 24, 10–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolson, P.J.A.; Bennell, K.L.; Dobson, F.L.; Van Ginckel, A.; Holden, M.A.; Hinman, R.S. Interventions to increase adherence to therapeutic exercise in older adults with low back pain and/or hip/knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 2017, 51, 791–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peek, K.; Sanson-Fisher, R.; Mackenzie, L.; Carey, M. Interventions to aid patient adherence to physiotherapist prescribed self-management strategies: A systematic review. Physiotherapy 2016, 102, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willett, M.; Duda, J.; Fenton, S.; Gautrey, C.; Greig, C.; Rushton, A. Effectiveness of behaviour change techniques in physiotherapy interventions to promote physical activity adherence in lower limb osteoarthritis patients: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0219482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbesman, M.; Mosley, L.J. Systematic review of occupation- and activity-based health management and maintenance interventions for community-dwelling older adults. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2012, 66, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kwasnicka, D.; Dombrowski, S.U.; White, M.; Sniehotta, F. Theoretical explanations for maintenance of behaviour change: A systematic review of behaviour theories. Health Psychol. Rev. 2016, 10, 277–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigg, C.; Borelli, B.; Maddock, J.; Dishman, R.K. A Theory of Physical Activity Maintenance. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 57, 544–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundel, M.; Sundel, S. Behavior Change in the Human Services. Chapter 12: Generalization and Maintenance of Behavior Change; SAGE: London, UK, 2005; pp. 167–178. [Google Scholar]

- Turk, D. Commentary: Generalization and miantenance of performance. In Fordyce’s Behavioral Methods for Chronic Pain and Illness; Main, C.J., Keefe, F., Jense, M., Vlayen, J., Vowles, K., Eds.; Wolters Kluver: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2015; pp. 415–427. [Google Scholar]

- Turk, D. A cognitive-behavioral perspective on the treatment of individuals experiencing chronic pain. Chapter 6. In Psychological Approaches to Pain Management, 3rd ed.; Turk, D., Gatchel, R., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 115–137. [Google Scholar]

- Bearne, L.M.; Walsh, N.E.; Jessep, S.; Hurley, M.V. Feasibility of an Exercise-Based Rehabilitation Programme for Chronic Hip Pain. Musculoskel Care 2011, 9, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laforest, S.; Nour, K.; Gignac, M.A.M.; Gauvin, L.; Parisien, M. The Role of Social Reinforcement in the Maintenance of Short-Term Effects after a Self-Management Intervention for Frail Housebound Seniors with Arthritis. Can. J. Aging 2012, 31, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laforest, S.; Nour, K.; Parisien, M.; Griskan, A.; Poirier, M.C.; Gignac, M. “I’m taking charge my arthritis”: Designing a targeted self-management program for frail seniors. J. Phys. Occup. Ther. Geriatr. 2008, 26, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholas, M.K.; Asghari, A.; Blyth, F.M.; Wood, B.M.; Murray, R.; McCabe, R.; Brnabic, A.; Beeston, L.; Corbett, M.; Sherrington, C.; et al. Long-term outcomes from training in self-management of chronic pain in an elderly population: A randomized controlled trial. Pain 2017, 158, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholas, M.K.; Asghari, A.; Blyth, F.M.; Wood, B.M.; Murray, R.; McCabe, R.; Brnabic, A.; Beeston, L.; Corbett, M.; Sherrington, C.; et al. Self-management intervention for chronic pain in older adults: A randomised controlled trial. Pain 2013, 154, 824–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitiello, M.V.; McCurry, S.M.; Shortreed, S.M.; Balderson, B.H.; Baker, L.D.; Keefe, F.J.; Rybarczyk, B.D.; Von Korff, M. Cognitive-behavioral treatment for comorbid insomnia and osteoarthritis pain in primary care: The lifestyles randomized controlled trial. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2013, 61, 947–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koffel, E.; Vitiello, M.V.; McCurry, S.M.; Rybarczyk, B.; Von Korff, M. Predictors of Adherence to Psychological Treatment for Insomnia and Pain: Analysis from a Randomized Trial. Clin. J. Pain. 2018, 34, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCurry, S.M.; Von Korff, M.; Vitiello, M.V.; Saunders, K.; Balderson, B.H.; Moore, A.L.; Rybarczyk, B.D. Frequency of comorbid insomnia, pain, and depression in older adults with osteoarthritis: Predictors of enrollment in a randomized treatment trial. J. Psychosom. Res. 2011, 71, 296–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Von Korff, M.; Vitiello, M.V.; McCurry, S.M.; Balderson, B.H.; Moore, A.L.; Baker, L.D.; Yarbro, P.; Saunders, K.; Keefe, F.J.; Rybarczyk, B.D. Group interventions for co-morbid insomnia and osteoarthritis pain in primary care: The lifestyles cluster randomized trial design. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2012, 33, 759–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Michie, S.; van Stralen, M.M.; West, R. The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Whiteley, J.; Williams, D.; Marcus, B. Adherence to exercise regimes. In Promoting Tretment Adherence; O’Donohue, W., Levensky, E., Eds.; SAGE: London, UK, 2006; pp. 307–320. [Google Scholar]

- Meichenbaum, D.; Turk, D. Facilitating Treatment Adherence; Plenum Press: London, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Sundel, M.; Sundel, K. Behavior Change in the Human Services. Chapter 1: Specifying Behavior; SAGE: London, UK, 2005; pp. 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ang, D.C.; Kaleth, A.S.; Bigatti, S.; Mazzuca, S.A.; Jensen, M.P.; Hilligoss, J.; Slaven, J.; Saha, C. Research to encourage exercise for fibromyalgia (REEF): Use of motivational interviewing, outcomes from a randomized-controlled trial. Clin. J. Pain 2013, 29, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ang, D.C.; Kaleth, A.S.; Bigatti, S.; Mazzuca, S.; Saha, C.; Hilligoss, J.; Lengerich, M.; Bandy, R. Research to Encourage Exercise for Fibromyalgia (REEF): Use of motivational interviewing design and method. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2011, 32, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aragonès, E.; Rambla, C.; López-Cortacans, G.; Tomé-Pires, C.; Sánchez-Rodríguez, E.; Caballero, A.; Miró, J. Effectiveness of a collaborative care intervention for managing major depression and chronic musculoskeletal pain in primary care: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 252, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beissner, K.L.; Bach, E.; Murtaugh, C.M.; Trifilio, M.; Henderson, C.R., Jr.; Barrón, Y.; Trachtenberg, M.A.; Reid, M.C. Translating Evidence-Based Protocols Into the Home Healthcare Setting. Home Healthc. Now 2017, 35, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bennell, K.L.; Kyriakides, M.; Hodges, P.W.; Hinman, R.S. Effects of two physiotherapy booster sessions on outcomes with home exercise in people with knee osteoarthritis: A randomized controlled trial. Arthr. Care Res. 2014, 66, 1680–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bennell, K.L.; Keating, C.; Lawford, B.J.; Kimp, A.J.; Egerton, T.; Brown, C.; Kasza, J.; Spiers, L.; Proietto, J.; Sumithran, P.; et al. Better Knee, Better Me™: Effectiveness of two scalable health care interventions supporting self-management for knee osteoarthritis-protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2020, 21, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennell, K.; Nelligan, R.K.; Schwartz, S.; Kasza, J.; Kimp, A.; Crofts, S.J.; Hinman, R.S. Behavior Change Text Messages for Home Exercise Adherence in Knee Osteoarthritis: Randomized Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e21749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourgault, P.; Lacasse, A.; Marchand, S.; Courtemanche-Harel, R.; Charest, J.; Gaumond, I.; Barcellos de Souza, J.; Choinière, M. Multicomponent interdisciplinary group intervention for self-management of fibromyalgia: A mixed-methods randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0126324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bove, A.M.; Lynch, A.D.; Ammendolia, C.; Schneider, M. Patients’ experience with nonsurgical treatment for lumbar spinal stenosis: A qualitative study. Spine J. 2018, 18, 639–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, B.; Veljanova, I.; Schabrun, S.; Chipchase, L. Integrating culturally informed approaches into physiotherapy assessment and treatment of chronic pain: A pilot randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e021999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, B.; Veljanova, I.; Schabrun, S.; Chipchase, L. Integrating culturally informed approaches into the physiotherapy assessment and treatment of chronic pain: Protocol for a pilot randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e014449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, M.; Walker, R.; Aitken, L.M.; Freeman, A.; Pavey, S.; Cantrill, R. Pre-operative self-efficacy education vs. usual care for patients undergoing joint replacement surgery: A pilot randomised controlled trial. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2016, 30, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dziedzic, K.S.; Healey, E.L.; Porcheret, M.; Ong, B.N.; Main, C.J.; Jordan, K.P.; Lewis, M.; Edwards, J.J.; Jinks, C.; Morden, A.; et al. Implementing the NICE osteoarthritis guidelines: A mixed methods study and cluster randomised trial of a model osteoarthritis consultation in primary care--the Management of OsteoArthritis In Consultations (MOSAICS) study protocol. Implement. Sci. 2014, 9, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dziedzic, K.S.; Healey, E.L.; Porcheret, M.; Afolabi, E.K.; Lewis, M.; Morden, A.; Jinks, C.; McHugh, G.A.; Ryan, S.; Finney, A.; et al. Implementing core NICE guidelines for osteoarthritis in primary care with a model consultation (MOSAICS): A cluster randomised controlled trial. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2018, 26, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kennedy, A.; Bower, P.; Reeves, D.; Blakeman, T.; Bowen, R.; Chew-Graham, C.; Eden, M.; Fullwood, C.; Gaffney, H.; Gardner, C.; et al. Implementation of self management support for long term conditions in routine primary care settings: Cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2013, 346, f2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Edbrooke, L.; Denehy, L.; Granger, C.L.; Kapp, S.; Aranda, S. Home-based rehabilitation in inoperable non-small cell lung cancer-the patient experience. Support. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elander, J.; Robinson, G.; Morris, J. Randomized trial of a DVD intervention to improve readiness to self-manage joint pain. Pain 2011, 152, 2333–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Geraghty, A.W.A.; Stanford, R.; Stuart, B.; Little, P.; Roberts, L.C.; Foster, N.E.; Hill, J.C.; Hay, E.M.; Turner, D.; Malakan, W.; et al. Using an internet intervention to support self-management of low back pain in primary care: Findings from a randomised controlled feasibility trial (SupportBack). BMJ Open 2018, 8, e016768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gustavsson, C.; Denison, E.; von Koch, L. Self-Management of Persistent Neck Pain: Two-Year Follow-up of a Randomized Controlled Trial of a Multicomponent Group Intervention in Primary Health Care. Spine 2011, 36, 2105–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinman, R.S.; Lawford, B.J.; Campbell, P.K.; Briggs, A.M.; Gale, J.; Bills, C.; French, S.D.; Kasza, J.; Forbes, A.; Harris, A.; et al. Telephone-Delivered Exercise Advice and Behavior Change Support by Physical Therapists for People with Knee Osteoarthritis: Protocol for the Telecare Randomized Controlled Trial. Phys. Ther. 2017, 97, 524–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahn, P.; Kuss, O.; Schmidt, H.; Bauer, A.; Kitzmantel, M.; Jordan, K.; Krasemann, S.; Landenberger, M. Improvement of pain-related self-management for cancer patients through a modular transitional nursing intervention: A cluster-randomized multicenter trial. Pain 2014, 155, 746–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jernelöv, S.; Lekander, M.; Blom, K.; Rydh, S.; Ljótsson, B.; Axelsson, J.; Kaldo, V. Efficacy of a behavioral self-help treatment with or without therapist guidance for co-morbid and primary insomnia—A randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry 2012, 12, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kahan, B.C.; Diaz-Ordaz, K.; Homer, K.; Carnes, D.; Underwood, M.; Taylor, S.J.; Bremner, S.A.; Eldridge, S. Coping with persistent pain, effectiveness research into self-management (COPERS): Statistical analysis plan for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2014, 15, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, L.W.; Harris, R.E.; Murphy, S.L.; Tsodikov, A.; Struble, L. Feasibility of a Randomized Controlled Trial of Self-Administered Acupressure for Symptom Management in Older Adults with Knee Osteoarthritis. J. Altren. Complement. Med. 2016, 22, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Littlewood, C.; Malliaras, P.; Mawson, S.; May, S.; Walters, S.J. Self-managed loaded exercise versus usual physiotherapy treatment for rotator cuff tendinopathy: A pilot randomised controlled trial. Physiotherapy 2014, 100, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lonsdale, C.; Hall, A.M.; Murray, A.; Williams, G.C.; McDonough, S.M.; Ntoumanis, N.; Owen, K.; Schwarzer, R.; Parker, P.; Kolt, G.S.; et al. Communication Skills Training for Practitioners to Increase Patient Adherence to Home-Based Rehabilitation for Chronic Low Back Pain: Results of a Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch. Physl. Med. Rehabil. 2017, 98, 1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Low, M.Y.; Lacson, C.; Zhang, F.; Kesslick, A.; Bradt, J. Vocal Music Therapy for Chronic Pain: A Mixed Methods Feasibility Study. J. Altren. Complement. Med. 2020, 26, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mars, T.; Ellard, D.; Carnes, D.; Homer, K.; Underwood, M.; Taylor, S.J. Fidelity in complex behaviour change interventions: A standardised approach to evaluate intervention integrity. BMJ Open 2013, 3, e003555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Taylor, S.J.C.; Carnes, D.; Homer, K.; Pincus, T.; Kahan, B.C.; Hounsome, N.; Eldridge, S.; Spencer, A.; Diaz-Ordaz, K.; Rahman, A.; et al. Programme Grants for Applied Research. In Improving the Self-Management of Chronic Pain: COping with Persistent Pain, Effectiveness Research in Self-Management (COPERS); NIHR Journals Library, Southampton University (UK): Southampton, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Matthias, M.S.; Bair, M.J.; Ofner, S.; Heisler, M.; Kukla, M.; McGuire, A.B.; Adams, J.; Kempf, C.; Pierce, E.; Menen, T.; et al. Peer Support for Self-Management of Chronic Pain: The Evaluation of a Peer Coach-Led Intervention to Improve Pain Symptoms (ECLIPSE) Trial. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCusker, J.; Cole, M.G.; Yaffe, M.; Strumpf, E.; Sewitch, M.; Sussman, T.; Ciampi, A.; Lavoie, K.; Belzile, E. Adherence to a depression self-care intervention among primary care patients with chronic physical conditions: A randomised controlled trial. Health Educ. J. 2016, 75, 767–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehlsen, M.; Hegaard, L.; Ørnbøl, E.; Jensen, J.S.; Fink, P.; Frostholm, L. The effect of a lay-led, group-based self-management program for patients with chronic pain: A randomized controlled trial of the Danish version of the Chronic Pain Self-Management Programme. Pain 2017, 158, 1437–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Frostholm, L.; Hornemann, C.; Ørnbøl, E.; Fink, P.; Mehlsen, M. Using Illness Perceptions to Cluster Chronic Pain Patients: Results From a Trial on the Chronic Pain Self-Management Program. Clin. J. Pain 2018, 34, 991–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestre, S.; Calais, C.; Gaillard, G.; Nou, M.; Pasqualini, M.; Ben Amor, C.; Quere, I. Interest of an auto-adjustable nighttime compression sleeve (MOBIDERM® Autofit) in maintenance phase of upper limb lymphedema: The MARILYN pilot RCT. Supp. Care Cancer 2017, 25, 2455–2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nevedal, D.C.; Wang, C.; Oberleitner, L.; Schwartz, S.; Williams, A.M. Effects of an individually tailored Web-based chronic pain management program on pain severity, psychological health, and functioning. J. Med. Intern. Res. 2013, 15, e201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oesch, P.; Kool, J.; Fernandez-Luque, L.; Brox, E.; Evertsen, G.; Civit, A.; Hilfiker, R.; Bachmann, S. Exergames versus self-regulated exercises with instruction leaflets to improve adherence during geriatric rehabilitation: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2017, 17, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reed, R.L.; Roeger, L.; Howard, S.; Oliver-Baxter, J.M.; Battersby, M.W.; Bond, M.; Osborne, R.H. A self-management support program for older Australians with multiple chronic conditions: A randomised controlled trial. Med. J. Austr. 2018, 208, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saner, J.; Bergman, E.M.; de Bie, R.A.; Sieben, J.M. Low back pain patients’ perspectives on long-term adherence to home-based exercise programmes in physiotherapy. Musculoskel. Sci. Pract. 2018, 38, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saner, J.; Kool, J.; Sieben, J.M.; Luomajoki, H.; Bastiaenen, C.H.; de Bie, R.A. A tailored exercise program versus general exercise for a subgroup of patients with low back pain and movement control impairment: A randomised controlled trial with one-year follow-up. Man. Ther. 2015, 20, 672–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, B.E.; Hendrick, P.; Bateman, M.; Moffatt, F.; Rathleff, M.S.; Selfe, J.; Smith, T.O.; Logan, P. Study protocol: A mixed methods feasibility study for a loaded self-managed exercise programme for patellofemoral pain. Pilot. Feasibil. Stud. 2018, 4, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Smith, B.E.; Hendrick, P.; Bateman, M.; Moffatt, F.; Rathleff, M.S.; Selfe, J.; Smith, T.O.; Logan, P. A loaded self-managed exercise programme for patellofemoral pain: A mixed methods feasibility study. BMC Musculoskel. Disord. 2019, 20, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suman, A.; Schaafsma, F.G.; Elders, P.J.; van Tulder, M.W.; Anema, J.R. Cost-effectiveness of a multifaceted implementation strategy for the Dutch multidisciplinary guideline for nonspecific low back pain: Design of a stepped-wedge cluster randomised controlled trial. BMC Publ. Health 2015, 15, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xiao, X.; Wang, J.; Gu, Y.; Cai, Y.; Ma, L. Effect of community based practice of Baduanjin on self-efficacy of adults with cardiovascular diseases. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0200246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zadro, J.R.; Shirley, D.; Simic, M.; Mousavi, S.J.; Ceprnja, D.; Maka, K.; Sung, J.; Ferreira, P. Video-Game–Based Exercises for Older People With Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Controlledtable Trial (GAMEBACK). Phys. Ther. 2019, 99, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zgierska, A.E.; Burzinski, C.A.; Cox, J.; Kloke, J.; Singles, J.; Mirgain, S.; Stegner, A.; Cook, D.B.; Bačkonja, M. Mindfulness Meditation-Based Intervention Is Feasible, Acceptable, and Safe for Chronic Low Back Pain Requiring Long-Term Daily Opioid Therapy. J. Altren. Complement. Med. 2016, 22, 610–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Databases (search date 19 October 2020) (MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINAHL Plus) via EBSCOhost, PubMed, Web of Science Core Search restrictions: English language, “humans” years 2010–2020 Search terms EBSCOhost [All Fields]: “self-management” and pain and (adherence or maintenance) = 599 hits. “self-management” and pain and (adherence or maintenance) age limit of 65+ = 105 hits remaining from the initial 599. “self-management” and pain and (adherence or maintenance) and (RCT or randomized controlled trial) with age limit of 65+ = 34 hits remaining of the previous 105; after duplicates were removed, 27 hits remained. PubMed [All Fields]: “self-management” and pain and (adherence or maintenance) and (RCT or randomized controlled trial) = 51 hits; with age limit of 65+ = 21 hits; duplicates removed in comparison to EBSCOhost hits = 7 hits remaining. Web of Science Core [All Fields]: “self-management” and pain and (adherence or maintenance) and (RCT or randomized controlled trial) = 82 hits; + musculoskeletal = 12 hits remaining of the initial 82 hits; after the duplicates were removed in respect to the EBSCOhost and PubMed hits, 9 hits remained. n = the full texts of 43 studies were read and evaluated regarding the inclusion criteria (EBSCOhost; 27 hits + PubMed; 7 hits + Web of Science Core; 9 hits = 43 hits). Furthermore, 11 papers were reviewed for details on the interventions included in the studies eligible to be included in this study, yielding a total of 54 studies to be evaluated. |

| Reference Country | Aim | Study Population | Experimental Intervention, Fulfilment of the Criteria for a Self-Management Programme and Intervention for Adherence and/or Maintenance | Control Intervention | Results of the Self-Management Programme on Patient Outcomes | Measurement Method and Results of the Outcomes for Adherence and Maintenance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bearne et al. [33] UK | The aim of this feasibility randomized controlled trial was to decrease pain intensity and disability in patients with chronic hip pain. | n = 48 Mean age was 66 years, 34 women, mean time for hip pain was 5 years. The participants were recruited from general practitioner primary care clinics. The initial assessments were performed in physiotherapy departments. | Rehabilitation group: Usual care and 75-min group exercise that was tailored to the individual (progressively increased strengthening and stretching of the lower body, cycling, functional balance and co-ordination) and self-management sessions (education was provided through interactive discussions of coping strategies, pain control, joint protection, self-care, problem solving for lifestyle changes that would promote joint health and self-management. The importance of body weight and integrating exercises in a daily routine were emphasized. A book about the discussion topics was given) with a physiotherapist 2 times per week for 5 weeks. Outpatient treatment was provided at a primary care hospital. In the end, a home exercise programme was implemented. * Fulfilment of Barlow et al. [7] criteria for self-management program: Three scores of yes (1, 2 and 4), two scores of partly (3 and 5) one score of unclear (6). No intervention components explicitly targeted adherence to or the maintenance of the exercise or the self-management programme by methods other than discussing the importance of performing these behaviours in a daily routine. | Usual care group: Routine management by the general practitioner. | Measures: Western Ontario and McMaster universities osteoarthritis index, (WOMAC). The physical subscale of the WOMAC was the main outcome, and the general WOMAC, pain, Arthritis Self-efficacy scale, Hospital anxiety and depression scale, and Objective functional performance were assessed There were no significant differences between the groups in any of the measures. The within-group effect sizes for the experimental condition showed low-to-medium effects at the 6-week and 6-month follow ups. | Adherence measure: Adherence to the intervention programme was measured by the percentage of attendance in the experimental intervention, which was 81%. No measures of the maintenance of pain self-management behaviours were reported. The maintenance of the treatment effect showed no significant differences between groups at the 6-month follow up. |

| Laforest et al. [34] Detailed intervention description by Laforest et al. [35] Canada | This was a three-group randomized trial: wait list- group; self-management programme group; self-management programme with maintenance components group. The aim was to study the social reinforcement effects delivered post-intervention of a self-management programme. | n = 113 Mean age was 72, 90% women, participants had osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis with moderate to severe pain intensity. Recruited from community health services centres by home care case managers. | There were two experimental conditions: self-management programme and self-management programme with maintenance intervention components. Self-management intervention: one hour per week for 6 weeks at the participant’s home, administered by a trained health care practitioner. Information, discussion and reinforcement was provided on exercise, relaxation, pain management, joint protection management, energy management, coping with negative emotions, available support, goal formulation, action plan, review of behavioural change success and barriers. * Fulfilment of Barlow et al. [7] criteria for self-management program: Four Yes (1, 2, 3 and 6), one Unclear (5), one No (4). No intervention components targeting adherence on the self-management programme were reported. Maintenance intervention consisted of social reinforcement with phone calls to the participants after the self-management programme. This consisted of 8 phone calls during 6 months. The calls were done by trained volunteers who had arthritis themselves. A detailed interview guide was used. The calls included discussion about action plan, revising goals, controlling pain, medication management, exercise, relaxation, positive feedback, problem-solving strategies, and energy management. | Control group: waiting list. | Outcome measures: Western Ontario and McMaster universities osteoarthritis index (WOMAC) for functional limitations. Arthritis Helplessness Inventory. Coping effectiveness. Post-intervention results showed significant differences between groups in favour to experimental condition in WOMAC and helplessness. At 10 months post randomization follow up the results were not maintained when the two experimental groups were analysed together. | No measures targeting adherence to the self-management programme were reported. No measures for the maintenance of pain self-management behaviours were reported. The maintenance of the treatment effect was measured 10 months after the randomization with the same outcome measures as mentioned for the self-management programme effect analyses. The results showed that the experimental condition with added maintenance component was significantly more effective in WOMAC compared to the condition without this component. |

| Nicholas et al. [36] Detailed intervention description by Nicholas et al. [37] Australia | The aim was to study the effects on disability, pain, mood, beliefs and functional reach between three groups; cognitive behavioural-based pain self-management group (PSM), exercise-attention group (EAC), and waiting list group (WL). | n = 141, mean age was 74 years, 63% of the participants were women, the median pain duration was 6 years, and the participants were recruited from the Pain Management and Research Centre in Sydney. | Two weekly two-hour sessions were held for four weeks. A psychologist and physiotherapist administered all the sessions together. Exercises and skills were practised during the sessions and at home. The patients received a “Manage your pain” book for information and educational purposes. The intervention included the self-monitoring of homework, the reinforcement of home tasks at each session, goal setting, activity pacing, arousal reduction, fear-avoidance management, managing flare-ups, problem solving, communication skills, stretching, aerobic, strengthening exercises, step-ups, walking. * Fulfilment of Barlow et al. [7] criteria for self-management program: Four scores of yes (1, 2, 3, 5 and 6) and one score of no (4). Adherence components were not explicitly described but the following were reported: encouragement to rehearsal of exercise and other skills at home, self-monitoring of training at home, reinforcement based on self-monitoring results. No intervention components explicitly targeted maintenance of the self-management programme. | There were two control conditions: Exercise-attention group (EAC) and waiting list group (WL) WL did not have any treatment. EAC intervention included two weekly two-hour sessions during four weeks and consisted of discussions of pain and its impact, stretching, aerobic, strengthening, step-ups, walking. A psychologist and physiotherapist administered all the sessions together. No encouragement was provided to perform the exercises at home, no self-monitoring of the exercises was performed. | Outcome measures: Roland & Morris Disability Questionnaire- Modified, Depression Anxiety Stress Scale, usual pain intensity and pain-related distress, 6-min walk test, functional reach for testing balance, catastrophizing scale of the Pain response Self-statements, Tampa Scale of Kinesio-phobia, Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire In short-term the PSM was significantly better in disability, pain distress, mood, pain beliefs, and functional reach compared to EAC and WL. There were no differences between EAC and WL. | Adherence measure: Attendance in the treatment sessions was set on 75% or more to have been completed the treatment. At one month follow up the percentage of non-completers varied between 11–25%, WL having the largest number of non-completers. The short-term adherence was 75% in WL, 89% in EAC and 88% in PSM. No measures for maintenance of pain self-management behaviour were reported. Maintenance of treatment effect at one year follow up: PSM group had maintained their treatment effects in pain-related disability, pain distress, pain intensity, depression and fear-avoidance beliefs significantly better than the EAC group. There was no data from the WL group at one year. |

| Vitello et al. [38] Detailed intervention description by Koffel et al., McCurry et al. and Von Korf et al. [39,40,41] USA | The aim was to investigate differences in pain and sleep outcomes between three groups of patients with osteoarthritis and insomnia. The three conditions were: cognitive-behavioural therapy for pain and insomnia (CBT-PI); cognitive-behavioural pain coping skills intervention (CBT-P); education-only (EOC) | n = 367 The mean age was 73 years, and 78.5% of the participants were women. The participants were paid volunteers who had clinically significant osteoarthritis pain (Grade II-IV in Graded Chronic Pain Scale) and insomnia and were members of a health maintenance organization “Group Health”. | The experimental groups had six weekly, 1.5 h treatment sessions for practice + homework. The CBT-PI intervention included education on pain and sleep management, sleep hygiene, sleep restriction, activity and sleep goal setting, relaxation, pleasant activity and sleep scheduling, activity pacing, a review of the schedule, problem solving, automatic thoughts, and a maintenance plan. The CBT-P intervention included education on pain and sleep management, activity goal setting, relaxation, pleasant activity scheduling, activity pacing, problem solving, automatic thoughts, and a maintenance plan. * Fulfilment of the Barlow et al. [7] criteria for a self-management program: Four scores of yes (1, 2, 3 and 6), one score of unclear (5), and one score of partly (4). No intervention components targeting adherence to the self-management program were reported. There was a “maintenance plan” as part of the intervention. No details were reported about this. | Six weekly, 1.5 h treatment sessions, no practices or homework. The EOC intervention included education on pain, sleep and medication management, alternative treatments, nutrition, memory and communication with health care, maintenance plan. | Outcome measures: Graded Chronic Pain Scale (pain intensity and pain interference) Insomnia Severity Index Arthritis Impact Measurement Scale Sleep efficiency with Actiwatch; % of daily time in bed. The two- and nine-month follow-ups showed that regarding some of the sleep-related measures the CBT-PI and CBT-P groups were significantly more effective than was the EOC. | Adherence measures: The attendance rate in the first session and four or more of the six possible sessions was between 92–94% in each of the three groups. Treatment acceptability level was the strongest predictor of adherence to treatment sessions. No measures for maintenance of pain self-management behaviour were reported. Maintenance of treatment effect at the nine-month follow-up: there were no group differences in pain severity or arthritis symptoms, but these issues improved in all patients over time. |

| Reference | Education (e.g., Pain Condition, Health Perceptions, Beliefs and Literacy, Treatment Knowledge and Skills) | Supervised, Individualised (Based on the Person’s Abilities) Exercise Programme, Written Exercise Instructions | Graded Exercise and Activity (e.g., Successively Increase the Intensity and Difficulty) | Mastery of the Exercise Programme to Increase Exercise Self-Efficacy (i.e., Mastery Increases Person’s Positive Beliefs of his/her Capability to Exercise) | Problem-Solving Skills for Adherence (e.g., Finding Solutions to Continue with a Behavior Despite Obstacles) | Coping with Obstacles for Adherence (e.g., Behavioral and Emotional Strategies to Overcome Obstacles) | Identifying Ways to Continue Exercising in the Future (e.g., Making Long-term Exercise Plans) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beinart et al. [19] | x | x | |||||

| Eisele et al. [10] | x | x | x | x | |||

| Ezzat et al. [20] | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Jordan et al. [21] | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| McLean et al. [22] | x | x | x | ||||

| Meade et al. [23] | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Nicolson et al. [24] | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Peek et al. [25] | x | x | x | ||||

| Willet et al. [26] | x | x | x | x |

| Reference | The Participants’ Readiness to Change (i.e., Identify Before Start How Prepared the Person is to Change a Behaviour) | An Exercise or Behavioural Contract (e.g., Make an Agreement when to Start, and How Much the Person is Willing to Engage Her-/Himself) | Goal Setting (e.g., SMART Goals; Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, Time Bound) | Self-Monitoring (e.g., Monitor with a Diary Number of Exercise Sessions, Thoughts and Emotions before and after the Sessions) | Reinforcement Procedures, Including Reinforcement by the Individual Him-/Herself (e.g., Plan with the Person What Kind of Rewards Would Work for that Individual for Increasing Adherence) | Coping with and Benefiting from Lapses (Behavioural and Emotional Strategies to Handle Lapses and how and what to Learn from the Lapses) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beinart et al. [19] | x | x | ||||

| Eisele et al. [10] | x | x | ||||

| Ezzat et al. [20] | x | x | ||||

| Jordan et al. [21] | x | x | x | x | x | |

| McLean et al. [22] | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Meade et al. [23] | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Nicolson et al. [24] | x | |||||

| Peek et al. [25] | x | x | ||||

| Willet et al. [26] | x | x | x |

| Reference | Booster Sessions with Problems Solving Discussions (e.g., Email or Phone Based Discussions of How the Upcoming Problems Have been Solved by the Person) | Feedback (e.g., Engage a Significant Other to Give Feedback on a Performance) | Social Support (e.g., Engage a Significant Other to Follow the Person to Walking Sessions) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beinart et al. [19] | |||

| Eisele et al. [10] | x | x | |

| Ezzat et al. [20] | |||

| Jordan et al. [21] | x | x | |

| McLean et al. [22] | x | ||

| Meade et al. [23] | x | x | |

| Nicolson et al. [24] | x | ||

| Peek et al. [25] | x | x | x |

| Willet et al. [26] | x | x |

| Reference | Resources (Psychological (e.g., Beliefs, Emotional Status) and Physical (e.g., Balance, Strength)) | Identify High-Risk Situations for Relapse (e.g., Write down Probable Situations that Would Increase the Risk for Ending a Desired Behaviour) | Pain Coping Skills (e.g., Behavioural and Emotional Strategies to Handle the Pain Flare ups) | Skills for Problem Solving in High-Risk Situations and Lapses (e.g., what Physical and Psychological Skills are Needed for the Person to Overcome Risk Situations and Lapses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kwasnicka et al. [28] | X | |||

| Nigg et al. [29] | X | |||

| Sundel et al. [30] | X | X | X | |

| Turk [31] | X | X | X | |

| Turk [32] | X | X | X |

| Reference | Habits (e.g., what Exercise Habits the Person has, and is There a Habit that Could be Used to Integrate Exercise with) | Goal Setting (e.g., SMART Goals; Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, Time Bound) | Self-Monitoring of Behaviour and Progress (e.g., Monitor with a Diary what Has been Done and how the Activities and Exercises are Increasing in Intensity and Difficulty) | Self-Regulation (e.g., How to Stand against Temptations to Stop the Desired Behaviour) | Self-Reinforcement (e.g., Plan with the Person what Kind of Rewards Would Work for that Individual for Increasing Maintenance) | Self-Efficacy for Problem Solving in High-Risk Situations to Address Both Barriers and Relapse (e.g., when Handling Lapses and Risk Situations Successfully Learn from Success and Reinforce One-Self) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kwasnicka et al. [28] | X | X | ||||

| Nigg et al. [29] | X | X | ||||

| Sundel et al. [30] | X | X | X | X | ||

| Turk [31] | X | X | X | X | ||

| Turk [32] | X | X | X | X |

| Reference | Environmental Triggers of Relapse (e.g., a TV-Program as Temptation to Skip the Exercise Session, Take Elevator instead of Stairs, Bad Weather Could Trigger Not Taking a Walk) | Problem Solving with High-Risk Situations and Lapses by Using Social Support and Social Reinforcement from Significant Others (e.g., Engage a Significant Other to Discuss What to Do with a Risk Situation and after a Lapse) |

|---|---|---|

| Kwasnicka et al. [28] | X | |

| Nigg et al. [29] | X | |

| Sundel et al. [30] | X | |

| Turk [31] | X | |

| Turk [32] | X |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Söderlund, A.; von Heideken Wågert, P. Adherence to and the Maintenance of Self-Management Behaviour in Older People with Musculoskeletal Pain—A Scoping Review and Theoretical Models. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 303. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10020303

Söderlund A, von Heideken Wågert P. Adherence to and the Maintenance of Self-Management Behaviour in Older People with Musculoskeletal Pain—A Scoping Review and Theoretical Models. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2021; 10(2):303. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10020303

Chicago/Turabian StyleSöderlund, Anne, and Petra von Heideken Wågert. 2021. "Adherence to and the Maintenance of Self-Management Behaviour in Older People with Musculoskeletal Pain—A Scoping Review and Theoretical Models" Journal of Clinical Medicine 10, no. 2: 303. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10020303

APA StyleSöderlund, A., & von Heideken Wågert, P. (2021). Adherence to and the Maintenance of Self-Management Behaviour in Older People with Musculoskeletal Pain—A Scoping Review and Theoretical Models. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(2), 303. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10020303