1. Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of mortality, morbidity, and healthcare costs in South Korea [

1]. Cardiovascular (CV) mortality has risen by 42.8% over the last decade. It has become the second leading cause of death in South Korea [

2]. According to the 2019 statistical office data, there were 62.42 deaths due to CVD per 100,000 individuals [

3]. The modifiable CV risk factors’ prevalence, such as smoking, dyslipidemia, obesity, and a sedentary lifestyle have continued to increase. The population is rapidly aging, with those aged 65 years and older projected to reach 37% by 2050 [

1,

4]. Death at the time of disease incidence, recurrence, and complications during follow-ups contribute to high mortality. There are also problems with decreased exercise capacity and quality of life. In addition, although most cases of CVD manifest clinically as an acute disease, they are actually chronic degenerative diseases that progress over a period of time. They thus need to be treated and managed as a chronic disease after discharge from the hospital [

5].

According to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Reviews of Health Care Quality of Korea 2012, the “paradox” of South Korea was that case–fatality rates were higher for acute myocardial infarction (AMI) than for OECD countries [

4]. This is despite having excellent acute hospital care. This was largely due to inadequate CVD risk factor prevention and suboptimal emergency response systems. Additional contributors are inadequate post-acute care and marked disparities between rural and urban communities. This “paradox” is likely to be reinforced by the insufficiency of cardiac rehabilitation (CR) services, leading to a higher number of readmitted patients [

4].

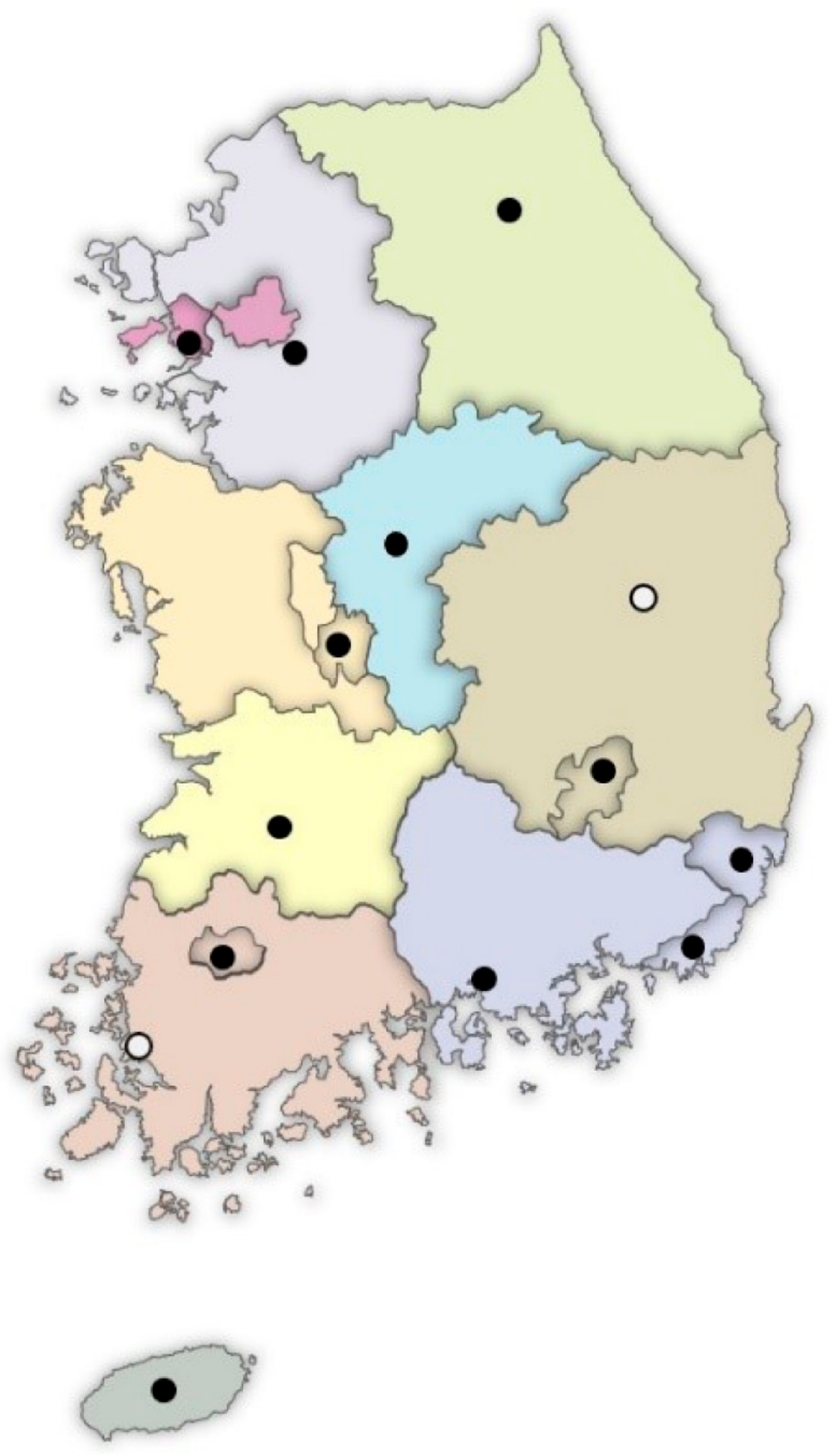

The Ministry of Health and Welfare (MHW) of South Korea has allocated government budgets from 2008 to install Regional Cardiocerebrovascular Centers (RCCs) in each province’s main cities, except for Seoul. Fourteen RCCs have been installed until the present (

Figure 1). The RCC project’s goal was to minimize the incidence of complications and mortality. It also intends to reduce the medical gaps among the South Korean regions. This is conducted through timely medical service provision across the country. It also aims to facilitate patients’ earlier return to society after their complete recovery [

6]. At the RCCs, standardized and high-quality care for AMI and stroke has been established. They are required to be equipped with CR facilities, equipment, and personnel. They also have regular performance measures conducted by the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KDCA) on behalf of the MHW (

Table 1). As a result, the RCC project has led to improved outcomes and less acute fatality rates for patients who arrived within this implementation period. However, there were no significant changes in the overall in-hospital mortality [

7]. Regarding post-acute care, the RCCs’ CR programs are expected to be a model for the Korean CR program. However, an evaluation study on their current status and achievements has not yet been reported. This study’s purpose is therefore to evaluate the current status of the CR programs in the RCCs. It also aims to make these data available for developing strategies to boost CR programs in Korea.

2. Materials and Methods

The study’s subjects were the RCCs in South Korea. We excluded the two newly designated RCCs (secondary hospitals) as the CR development processes were still ongoing. The CR program’s quality was also unsatisfactory as compared to that of existing RCCs, which are tertiary hospitals. A total of 12 RCCs participated in this study: Chonnam National University Hospital, Chungbuk National University Hospital, Chungnam National University Hospital, Dong-A University Hospital, Gyeongsang National University Hospital, Inha University Hospital, Jeju National University Hospital, Kangwon National University Hospital, Kyungpook National University Hospital, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Ulsan University Hospital, and Wonkwang University Hospital.

2.1. Development of CR Survey Forms

To examine CR’s current status in the 12 RCCs, the CR-General Questionnaire (CR-GQ) was developed after analyzing the national and international CR clinical practice guidelines (CPG) [

5,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. The Cardiac Rehabilitation-In Depth Questionnaire (CR-IDQ) was developed with reference to the CR evaluation tools of York University [

14,

15] and International Council of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation (ICCPR;

www.globalcardiacrehab.com, accessed on 9 September 2021) [

16]. To analyze the current status of RCC, CR-GQ examined the: kinds of procedures offered, amount of procedures or surgeries, CR program’s initiation, and CR in the institution’s delivery system. CR-IDQ investigates the: CR components, CR capacity (patient capacity to be served each year in the institute), CR density, outpatient CR program’s commencement time, CR team personnel, facility, supervised exercise program, CPR certification, and further details on the outpatient CR program. Detailed information on CR-GQ and CR-IDQ are available in the

Supplementary Materials thru online at

https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jcm10215079/s1,

Supplementary Materials S1: I. CR-GQ form,

Supplementary Materials S2: II. CR-IDQ form.

2.2. Dispatch of the Surveys

Printed copies of the CR-GQ were sent to the staff of the cardiology, cardiac surgery, and rehabilitation medicine departments of the 12 RCCs. Printed copies of the CR-IDQ were sent to the staff responsible for CR in the 12 RCCs. The printed surveys, project information, and an explanation of how to respond to the survey were sent in July 2020. An official letter of cooperation from the Korea National Institute of Health was included to increase the response rate. The surveys’ responses were entered in a Google survey format that was accessible through a QR code provided with the package or by connecting to

www.crsurvey.co.kr (accessed on 15 September 2020). The data were collected until 30 August 2020.

2.3. Confirmation of the Response

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the CR-GQ’s response rate was lower than expected. We initially planned to conduct a field survey if the response thereof was inadequate. However, field surveys were not possible as visitors’ access to hospitals was restricted due to the pandemic. Out of 44 responses to CR-GQ, the response rate was 59%. This excluded one case of duplicate response and cases with less than 50% completion. In all 12 RCCs, at least one response was received from the staff of the departments of cardiology and rehabilitation medicine. Responses from the staff of the cardiac surgeries were received from only six centers. All responses to the CR-IDQ were included in the study (N = 12, response rate 100%). The staff responsible for CR at each RCC reviewed and confirmed whether the number of candidates and CR participation rates in their RCCs from 1 July 2019, to 30 June 2020 were correct.

The overall performance achievement was evaluated based on the number of CR candidates, CR capacity, CR density, and CR participation rate. The number of CR candidates refers to the annual number of AMI admissions less the number of patients not indicated for CR referral. CR capacity refers to the median number of patients a program can serve annually. CR density refers to the annual number of CR candidates divided by the CR capacity [

17]. The CR participation rate refers to the number of outpatient CR enrollments divided by the number of inpatient CR referrals.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

To determine whether the CR performance is different among RCCs, we compared the data collected via the surveys from CR directors at the 12 RCCs. An ANOVA was performed to compare CR candidates, CR capacity, and CR density. The chi-square test was used to compare the proportion of patients with CR participation rates. All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) (version 19.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The level of significance was set at p < 0.05.

2.5. Ethics Statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Inje University Sanggye Paik Hospital, Korea (IRB No. SGPAIK202012010002-HE003). The need to obtain informed consent was waived due to the non-clinical nature of the study. No personal information (patient’s name, address, ID, phone number, hospital ID) were collected and thus the participants’ anonymity was preserved.

4. Discussion

CR is practiced in 111 countries globally [

17], and countries including the US, Canada, Europe, Japan, and Korea have published high-quality CPG [

5,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. Although the level of recommendation for CR is strong, the actual CR participation rate is only about 30–40% [

18]. Each nation is striving to increase the participation rate. However, this rate is only about 1.5% in Korea [

19], which is much lower than those of the other aforementioned countries. In addition, there are a lack of strategies for effective management in the community after patients’ discharge and for increasing treatment compliance. The continuum of care from the hospital to the community after patient discharge is very important for determining their long-term prognosis. Therefore, a state-led system needs to be established.

A comprehensive CR program was introduced in Korea around the late 1990s. Before the establishment of RCCs, only five private medical institutions had well-organized CR programs in South Korea. They were all in densely populated areas in the capital region. Before the regional hospitals in this study were granted RCC status by the MHW, they had no CR facility, equipment, or CR specialized staff. Since 2008, the MHW of South Korea has established 14 RCCs in different provinces nationwide. This includes 12 tertiary university hospitals and two general hospitals. The intention was to reduce the medical gaps in research, knowledge, and practice for AMIs and strokes among the regions in South Korea. There may be differences in the organization of nationwide infrastructure for the CV care systems in other countries. However, it is expected that RCCs serve as key units of organization to provide nationwide quality care for CVD in South Korea. Standardized, high-quality care for AMI and stroke has been established in the RCCs. Furthermore, equipment and maintenance of CR facilities and personnel are mandatory. Many of this study’s co-authors have published articles on CR’s status and impact on AMI’s prognosis [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. There has been an increasing acceptance of CR nationwide and an introduction of CR insurance benefits in February 2017. CR facilities have therefore increased by up to 46 centers nationwide. This includes RCCs. A growing number of medical institutions are preparing to establish CR programs. However, the CR participation rate is still very low and there are considerable differences in the CR programs’ activity levels among CR facilities [

19].

According to this study’s results, considering the number of CVD patients by region, the CR demand cannot be met by CR programs in the RCCs. In Daejeon-Chungnam, Chungbuk, Jeonbuk, Ulsan, and Jeju regions, RCCs were the only hospitals practicing CR. The history of CR programs at the RCCs ranges from 2 to 13 years. Regardless of the duration, the number of AMI patients, physicians’ interest in and will to practice CR, and regional socioeconomic characteristics contributed to the CR programs’ activity levels in each RCC. The CR capacity ranged from 50 to 500. The CR density varied from 0.42 to 7.36. RCCs with a CR density of more than one, due to low CR capacity, need to expand their CR capacity to sufficiently offer CR programs to their candidates. In particular, B, C, and D centers should endeavor to urgently improve their CR capacity to reserve their standardized patient quota.

At most RCCs, the facilities, equipment, and personnel required for CR were in place. However, there were some RCCs that concurrently utilized general rehabilitation facilities and personnel for CR. This practice should be reformed. At all RCCs, risk factor evaluation, CR evaluation, CR exercise prescription, exercise therapy under supervision, drug compliance monitoring, and CR education were performed. However, psychological evaluation, stress management, and vocational counseling were practiced at low rates. These components must also be added to the comprehensive CR program for all RCCs [

25,

26,

27].

The average RCCs’ CR referral rate was 97%. This is very high, which may be because nine RCCs (75%) used automatic referral systems. Furthermore, the medical staff reviewed the prescription for CR referral at three RCCs (25%). However, as compared to the inpatient CR referral rate, the outpatient CR participation rate was very low. The enrollment rate in (47%) and adherence to (17%) outpatient CR were much lower and showed deviations among the 12 RCCs. We are currently in the process of analyzing big data using health insurance claim data showing implementation status of CR in Korea including CR participation rate.

The factors that hinder participation may be a lack of understanding of the need for CR, lack of motivation, and various socioeconomic factors. These include time/distance/transport issues and the burden of paying CR fees. As compared to tertiary medical centers in Seoul and the metropolitan areas, the proportion of patients coming from farming/fishing villages, mountainous villages, and islands is relatively high at the RCCs. It is therefore difficult to maintain adherence to hospital-based outpatient CR. Grace et al. and a study by four institutions in Korea have reported similar barriers to CR [

28,

29].

Strategies are required to overcome these barriers at the patient, doctor, hospital, and policy levels [

30,

31]. According to this study’s results, the high average rate of CR referral (97%) is satisfactory. However, the low rate of CR enrollment (47%) and adherence (17%) to the outpatient CR programs are major challenges to be overcome regarding patient-centered strategies. First, to improve CR facilities’ accessibility, CR programs need to be established in more hospitals to form a denser CR network. According to a report on the global CR density status in 2019, the CR density in South Korea was 22. It ranked 27th out of 111 countries with CR programs [

17]. Thus, RCCs should be expanded for improving the CR capacity to meet the need in their region and a regional network system should be implemented through the new “Local Cardiocerebrovascular Center (LCC)” project. This is currently being developed by the government. It not only provides timely acute medical services but also provides post discharge outcome care across the country, including rural areas [

32]. For this second mission, CR programs’ installation should be made mandatory in all LCCs. The experience of CR programs in RCCs may play a central role in the establishment of CR programs in LCCs. RCCs may serve as leaders of CR networks in each region (CR hub). This may provide education and support for the LCCs and establish a CR network, where the centers may refer CR patients mutually. More flexible scheduling for outpatient CR, improvement in accessibility to CR facilities (location and direction signs) in hospitals, and more active utilization of home-based CR programs should be applied [

33,

34]. These include the development of standardized protocols and insurance fees, game type CR programs, and telehealth or mobile healthcare techniques. We are currently conducting a randomized controlled trials that applies hybrid CR and telerehabilitation, the strategies for improvement of CR participation, as subsequent research.

At a patient level, RCCs should provide self-efficacy counseling and education programs, psychological evaluation, and consultation to improve patients’ motivation. They could also provide specialized CR programs for elderly patients with severely reduced exercise capacity, transportation/mobility aid for the elderly, and CR participation incentives. These include reimbursement for transportation expenses or gifts for successful completion of the CR program. In addition, a CR co-pay relief program should be implemented to reduce the patients’ CR fee burden.

This study has several limitations that should be noted. First, it was based on questionnaire surveys. Since they were completed by at least one cardiologist, cardiac surgeon, or physiatrist, there is a possibility of response bias. Second, the COVID-19 pandemic adversely impacted the study’s response rate from the eligible sample. Third, since the CR in-depth questionnaires were completed by only a physiatrist, the surveys’ results may not reflect the cardiologists’ and cardiac surgeons’ perspectives. This was because the CR directors of all the RCCs were physiatrists. Future studies should include hospitals where CR directors are cardiologists or cardiac surgeons.

Despite these limitations, this study is meaningful, as it is the first study to examine and compare CR status in government-sponsored RCCs. The results showed that while RCCs are equipped with the necessary facilities, equipment, and personnel, not all the essential components are in place. More standardized clinical performance and quality measures should be used to improve the CR quality in RCCs [

20,

21]. The outpatient CR program is still not as active as the inpatient program. There are substantial gaps among the RCCs. Therefore, to improve CR in the RCCs, the attention and resources of the medical staff, hospital management, and standardization of the CR programs in the RCCs are required. In addition, patient-oriented CR programs should be more actively practiced to increase the rate of outpatient CR adherence. However, for the aforementioned strategies to be realized, effective governmental policy and financial support are required.

CR has been reimbursed by the Korean government since February 2017. There has yet to be a national systematic plan for improving CR implementation, and a state-controlled CR network has not yet been established as well. The activation of CR in Korea was somewhat delayed compared to other high-income countries. To overcome this situation, 12 government-driven RCCs to cover CR were established across the whole country. There are many countries where the status of CR is similar to Korea, or not yet activated. We believe it would be beneficial for such countries to refer to the situation in Korea.

Through three consecutive years of research, we intend to present strategies to improve CR participation in Korea. As the first step of this project, we investigated the current status of CR in Korea through a nationwide survey. This article, a part of the complete work, details the operating status of 12 RCCs established with government support.