Early Association Factors for Depression Symptoms in Pregnancy: A Comparison between Spanish Women Spontaneously Gestation and with Assisted Reproduction Techniques

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

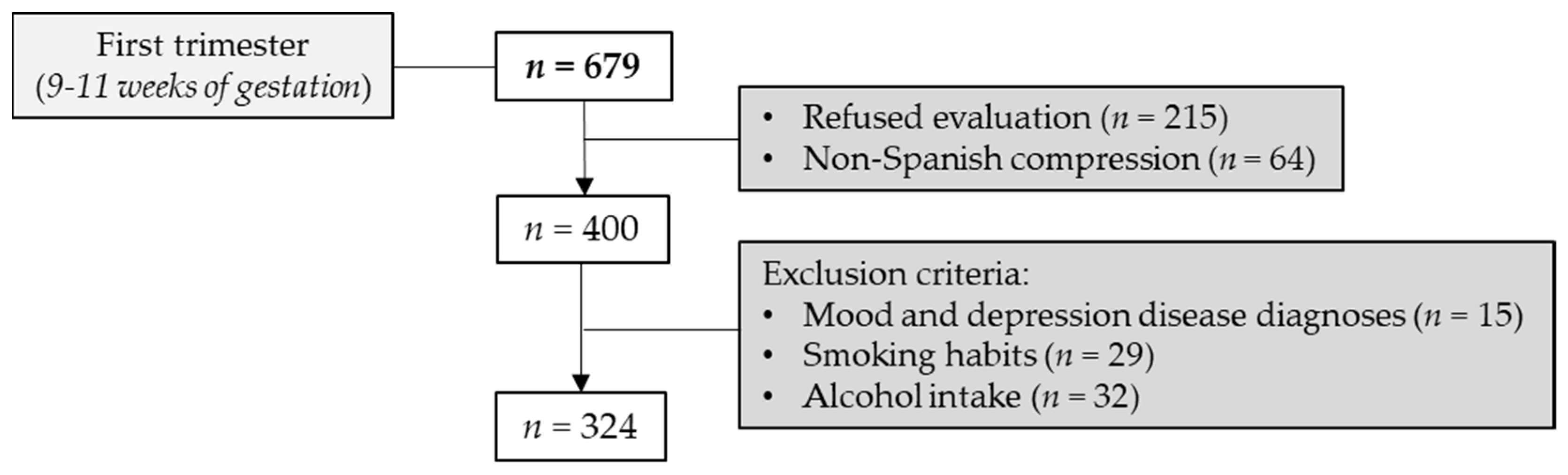

2.1. Cohort and Study Design

2.2. Maternal Psychological Instruments during Early Pregnancy

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics Related to ART and Depression Scale

3.2. Behavior of Psychological Variables with Depression Scale

3.3. Depression Scale and ART Models Controlled by Demographic and Psychological Variables

3.4. Depression Scale in a Subset of Women with ART

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Attali, E.; Yogev, Y. The Impact of Advanced Maternal Age on Pregnancy Outcome. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2021, 70, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varea, C.; Teran, J.M.; Bernis, C.; Bogin, B. The Impact of Delayed Maternity on Foetal Growth in Spain: An Assessment by Population Attributable Fraction. Women Birth 2018, 31, e190–e196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Frick, A.P. Advanced Maternal Age and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2021, 70, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szamatowicz, M. Assisted Reproductive Technology in Reproductive Medicine—Possibilities and Limitations. Ginekol. Pol. 2016, 87, 820–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Inhorn, M.C.; Patrizio, P. Infertility Around the Globe: New Thinking on Gender, Reproductive Technologies and Global Movements in the 21st Century. Hum. Reprod. Update 2015, 21, 411–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Melo-Martin, I. Assisted Reproductive Technology in Spain: Considering Women’s Interests. Camb. Q. Healthc. Ethics 2009, 18, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministerio de Sanidad, Consumo y Bienestar Social. Los Tratamientos de Reproducción Asistida en España Aumentan un 28% en los Últimos 5 Años. Available online: https://www.mscbs.gob.es/gabinete/notasPrensa.do?id=5067 (accessed on 13 September 2021).

- Hammarberg, K.; Fisher, J.R.; Wynter, K.H. Psychological and Social Aspects of Pregnancy, Childbirth and Early Parenting after Assisted Conception: A Systematic Review. Hum. Reprod. Update 2008, 14, 395–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gdanska, P.; Drozdowicz-Jastrzebska, E.; Grzechocinska, B.; Radziwon-Zaleska, M.; Wegrzyn, P.; Wielgos, M. Anxiety and Depression in Women Undergoing Infertility Treatment. Ginekol. Pol. 2017, 88, 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanhiser, J.; Steiner, A.Z. Psychosocial Aspects of Fertility and Assisted Reproductive Technology. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. N. Am. 2018, 45, 563–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, C.A.; Boivin, J.; Gibson, F.L.; Hammarberg, K.; Wynter, K.; Saunders, D.; Fisher, J. Age at First Birth, Mode of Conception and Psychological Wellbeing in Pregnancy: Findings from the Parental Age and Transition to Parenthood Australia (PATPA) Study. Hum. Reprod. 2011, 26, 1389–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Valoriani, V.; Lotti, F.; Lari, D.; Miccinesi, G.; Vaiani, S.; Vanni, C.; Coccia, M.E.; Maggi, M.; Noci, I. Differences in Psychophysical Well-being and Signs of Depression in Couples Undergoing their First Consultation for Assisted Reproduction Technology (ART): An Italian Pilot Study. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2016, 197, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, M.Z.; Kao, C.H.; Lin, K.C.; Hwang, J.L.; Puthussery, S.; Gau, M.L. Psychological Health of Women Who have Conceived using Assisted Reproductive Technology in Taiwan: Findings from a Longitudinal Study. BMC Women’s Health 2019, 19, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boekhorst, M.; Beerthuizen, A.; Endendijk, J.J.; van Broekhoven, K.; van Baar, A.; Bergink, V.; Pop, V. Different Trajectories of Depressive Symptoms during Pregnancy. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 248, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Kaaya, S.; Chai, J.; McCoy, D.C.; Surkan, P.J.; Black, M.M.; Sutter-Dallay, A.L.; Verdoux, H.; Smith-Fawzi, M.C. Maternal Depressive Symptoms and Early Childhood Cognitive Development: A Meta-Analysis. Psychol. Med. 2017, 47, 680–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biaggi, A.; Conroy, S.; Pawlby, S.; Pariante, C.M. Identifying the Women at Risk of Antenatal Anxiety and Depression: A Systematic Review. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 191, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yim, I.S.; Tanner Stapleton, L.R.; Guardino, C.M.; Hahn-Holbrook, J.; Dunkel Schetter, C. Biological and Psychosocial Predictors of Postpartum Depression: Systematic Review and Call for Integration. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2015, 11, 99–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lancaster, C.A.; Gold, K.J.; Flynn, H.A.; Yoo, H.; Marcus, S.M.; Davis, M.M. Risk Factors for Depressive Symptoms during Pregnancy: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 202, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ramezanzadeh, F.; Aghssa, M.M.; Abedinia, N.; Zayeri, F.; Khanafshar, N.; Shariat, M.; Jafarabadi, M. A Survey of Relationship between Anxiety, Depression and Duration of Infertility. BMC Women’s Health 2004, 4, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooney, K.L.; Domar, A.D. The Relationship between Stress and Infertility. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2018, 20, 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Soto-Balbuena, C.; Rodriguez, M.F.; Escudero Gomis, A.I.; Ferrer Barriendos, F.J.; Le, H.N.; Pmb-Huca, G. Incidence, Prevalence and Risk Factors Related to Anxiety Symptoms during Pregnancy. Psicothema 2018, 30, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ranjbar, F.; Warmelink, J.C.; Gharacheh, M. Prenatal Attachment in Pregnancy Following Assisted Reproductive Technology: A Literature Review. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2020, 38, 86–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gourounti, K. Psychological Stress and Adjustment in Pregnancy Following Assisted Reproductive Technology and Spontaneous Conception: A Systematic Review. Women Health 2016, 56, 98–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, H. Stress Management Programs. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences; Smelser, N.J., Baltes, P.B., Eds.; Pergamon: Oxford, UK, 2001; pp. 15184–15190. [Google Scholar]

- Witt, W.P.; Cheng, E.R.; Wisk, L.E.; Litzelman, K.; Chatterjee, D.; Mandell, K.; Wakeel, F. Preterm Birth in the United States: The Impact of Stressful Life Events Prior to Conception and Maternal Age. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104 (Suppl. 1), 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Bergh, B.R.H.; van den Heuvel, M.I.; Lahti, M.; Braeken, M.; de Rooij, S.R.; Entringer, S.; Hoyer, D.; Roseboom, T.; Raikkonen, K.; King, S.; et al. Prenatal Developmental Origins of Behavior and Mental Health: The Influence of Maternal Stress in Pregnancy. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2020, 117, 26–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Klonoff-Cohen, H. Female and Male Lifestyle Habits and IVF: What is Known and Unknown. Hum. Reprod. Update 2005, 11, 179–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feligreras-Alcala, D.; Frias-Osuna, A.; Del-Pino-Casado, R. Personal and Family Resources Related to Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms in Women during Puerperium. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramiro-Cortijo, D.; de la Calle, M.; Gila-Diaz, A.; Moreno-Jimenez, B.; Martin-Cabrejas, M.A.; Arribas, S.M.; Garrosa, E. Maternal Resources, Pregnancy Concerns, and Biological Factors Associated to Birth Weight and Psychological Health. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raisanen, S.; Lehto, S.M.; Nielsen, H.S.; Gissler, M.; Kramer, M.R.; Heinonen, S. Risk Factors for and Perinatal Outcomes of Major Depression during Pregnancy: A Population-Based Analysis during 2002–2010 in Finland. BMJ Open 2014, 4, e004883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, M.; Weinberger, T.; Chandy, A.; Schmukler, S. Depression during Pregnancy and Postpartum. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2016, 18, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gotzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; Strobe Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for Reporting Observational Studies. Int. J. Surg. 2014, 12, 1495–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B. The PHQ-9: Validity of a Brief Depression Severity Measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, M. Symptom Severity and Guideline-Based Treatment Recommendations for Depressed Patients: Implications of DSM-5’s Potential Recommendation of the PHQ-9 as the Measure of Choice for Depression Severity. Psychother. Psychosom. 2012, 81, 329–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez-Quevedo, C.; Rangil, T.; Sanchez-Planell, L.; Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L. Validation and Utility of the Patient Health Questionnaire in Diagnosing Mental Disorders in 1003 General Hospital Spanish Inpatients. Psychosom. Med. 2001, 63, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto-Meza, A.; Serrano-Blanco, A.; Penarrubia, M.T.; Blanco, E.; Haro, J.M. Assessing Depression in Primary Care with the PHQ-9: Can it be Carried out over the Telephone? J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2005, 20, 738–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marcos-Najera, R.; Le, H.N.; Rodriguez-Munoz, M.F.; Olivares Crespo, M.E.; Izquierdo Mendez, N. The Structure of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 in Pregnant Women in Spain. Midwifery 2018, 62, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbody, S.; Richards, D.; Brealey, S.; Hewitt, C. Screening for Depression in Medical Settings with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ): A Diagnostic Meta-Analysis. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2007, 22, 1596–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Manea, L.; Gilbody, S.; McMillan, D. A Diagnostic Meta-Analysis of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) Algorithm Scoring Method as a Screen for Depression. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2015, 37, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.; Lowe, B. A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Evans, K.; Morrell, C.J.; Spiby, H. Women’s Views on Anxiety in Pregnancy and the use of Anxiety Instruments: A Qualitative Study. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2017, 35, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Campayo, J.; Zamorano, E.; Ruiz, M.A.; Pardo, A.; Perez-Paramo, M.; Lopez-Gomez, V.; Freire, O.; Rejas, J. Cultural Adaptation into Spanish of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) Scale as a Screening Tool. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2010, 8, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Soto-Balbuena, C.; Rodriguez-Munoz, M.F.; Le, H.N. Validation of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in Spanish Pregnant Women. Psicothema 2021, 33, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gaxiola Romero, J.C.; Frias Armenta, M.; Hurtado Abril, M.F.; Salcido Noriega, L.C.; Figueroa Franco, M. Validacion Del Inventario De Resiliencia En Una Muestra Del Noroeste De Mexico. Enseñ. E Investig. En Psicol. 2011, 16, 73–83. [Google Scholar]

- González Lugo, S.; Gaxiola Romero, J.C.; Valenzuela Hernández, E.R. Apoyo Social Y Resiliencia: Predictores De Bienestar Psicológico En Adolescentes Con Suceso De Vida Estresante. Psicol. Y Salud 2018, 28, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaxiola Romero, J.C.; González Lugo, S.; Gaxiola Villa, E. Autorregulación, Resiliencia Y Metas Educativas: Variables Protectoras Del Rendimiento Académico De Bachilleres. Rev. Colomb. Psicol. 2013, 22, 241–252. [Google Scholar]

- Muniz, J.; Fonseca-Pedrero, E. Diez Pasos Para La Construccion De Un Test. Psicothema 2019, 31, 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Green, J.M.; Kafetsios, K.; Statham, H.E.; Snowdon, C.M. Factor Structure, Validity and Reliability of the Cambridge Worry Scale in a Pregnant Population. J. Health Psychol. 2003, 8, 753–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lara, M.A.; Navarro, C.; Navarrete, L. The Influence of Life Events and Social Support in a Psycho-Educational Intervention for Women with Depression. Salud Pública Méx. 2004, 46, 378–387. [Google Scholar]

- Lara, M.A.; Navarro, C.; Navarrete, L.; Le, H. Retention Rates and Potential Predictors in a Longitudinal Randomized Control Trial to Prevent Postpartum Depression. Salud Mental 2010, 33, 429–436. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, C.T. Revision of the Postpartum Depression Predictors Inventory. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2002, 31, 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Records, K.; Rice, M.; Beck, C.T. Psychometric Assessment of the Postpartum Depression Predictors Inventory-Revised. J. Nurs. Meas. 2007, 15, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Muñoz, M.D.L.F.; Vallejo Slocker, L.; Olivares Crespo, M.E.; Izquierdo Méndez, N.; Soto, C.; Le, H. Psychometric Properties of Postpartum Depression Predictors Inventory- Revised- Prenatal Version in a Sample of Spanish Pregnant Women. Rev. Esp. Salud Publica 2017, 91, 91. [Google Scholar]

- Ibarra-Yruegas, B.; Lara, M.A.; Navarrete, L.; Nieto, L.; Kawas Valle, O. Psychometric Properties of the Postpartum Depression Predictors Inventory-Revised for Pregnant Women in Mexico. J. Health Psychol. 2018, 23, 1415–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcos-Najera, R.; Rodriguez-Munoz, M.F.; Soto Balbuena, C.; Olivares Crespo, M.E.; Izquierdo Mendez, N.; Le, H.N.; Escudero Gomis, A. The Prevalence and Risk Factors for Antenatal Depression among Pregnant Immigrant and Native Women in Spain. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2020, 31, 564–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, S.D.; Han, Z.; Mulla, S.; Murphy, K.E.; Beyene, J.; Ohlsson, A.; Knowledge Synthesis Group. Preterm Birth and Low Birth Weight among in Vitro Fertilization Singletons: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2009, 146, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhaya, N.; Arulkumaran, S. Reproductive Outcomes after in-Vitro Fertilization. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2007, 19, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinveld, J.H.; Timmermans, D.R.; de Smit, D.J.; Ader, H.J.; van der Wal, G.; ten Kate, L.P. Does Prenatal Screening Influence Anxiety Levels of Pregnant Women? A Longitudinal Randomised Controlled Trial. Prenat. Diagn. 2006, 26, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, R.M.; Melotti, R.; Heron, J.; Joinson, C.; Stein, A.; Ramchandani, P.G.; Evans, J. Disruption to the Development of Maternal Responsiveness? The Impact of Prenatal Depression on Mother-Infant Interactions. Infant Behav. Dev. 2012, 35, 613–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, R.S.; Brandon, A.R. Adolescents, Pregnancy, and Mental Health. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2014, 27, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, J.; Petzoldt, J.; Einsle, F.; Beesdo-Baum, K.; Hofler, M.; Wittchen, H.U. Risk Factors and Course Patterns of Anxiety and Depressive Disorders during Pregnancy and After Delivery: A Prospective-Longitudinal Study. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 175, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas, A.; Raza, N.; Lodhi, H.W.; Muhammad, Z.; Jamal, M.; Rehman, A. Psychosocial Factors of Antenatal Anxiety and Depression in Pakistan: Is Social Support a Mediator? PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0116510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yanikkerem, E.; Ay, S.; Mutlu, S.; Goker, A. Antenatal Depression: Prevalence and Risk Factors in a Hospital Based Turkish Sample. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2013, 63, 472–477. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Groves, A.K.; Kagee, A.; Maman, S.; Moodley, D.; Rouse, P. Associations between Intimate Partner Violence and Emotional Distress among Pregnant Women in Durban, South Africa. J. Interpers. Violence 2012, 27, 1341–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rubertsson, C.; Hellstrom, J.; Cross, M.; Sydsjo, G. Anxiety in Early Pregnancy: Prevalence and Contributing Factors. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2014, 17, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, N.; Murthy, S.; Singh, A.K.; Upadhyay, V.; Mohan, S.K.; Joshi, A. Assessment of Burden of Depression during Pregnancy among Pregnant Women Residing in Rural Setting of Chennai. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2015, 9, LC08–LC12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lydsdottir, L.B.; Howard, L.M.; Olafsdottir, H.; Thome, M.; Tyrfingsson, P.; Sigurdsson, J.F. The Mental Health Characteristics of Pregnant Women with Depressive Symptoms Identified by the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2014, 75, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Cui, Y.; Li, J. Prevalence and Predictors of Antenatal Depressive Symptoms among Chinese Women in their Third Trimester: A Cross-Sectional Survey. BMC Psychiatry 2015, 15, 66–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Abuidhail, J.; Abujilban, S. Characteristics of Jordanian Depressed Pregnant Women: A Comparison Study. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2014, 21, 573–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mautner, E.; Stern, C.; Deutsch, M.; Nagele, E.; Greimel, E.; Lang, U.; Cervar-Zivkovic, M. The Impact of Resilience on Psychological Outcomes in Women after Preeclampsia: An Observational Cohort Study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2013, 11, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Maxson, P.J.; Edwards, S.E.; Valentiner, E.M.; Miranda, M.L. A Multidimensional Approach to Characterizing Psychosocial Health during Pregnancy. Matern. Child Health J. 2016, 20, 1103–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, A.J.; Stewart, D.E. Resilience in International Migrant Women Following Violence Associated with Pregnancy. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2014, 17, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Haeken, S.; Braeken, M.A.K.A.; Nuyts, T.; Franck, E.; Timmermans, O.; Bogaerts, A. Perinatal Resilience for the First 1,000 Days of Life. Concept Analysis and Delphi Survey. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 563432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebbesen, S.M.; Zachariae, R.; Mehlsen, M.Y.; Thomsen, D.; Hojgaard, A.; Ottosen, L.; Petersen, T.; Ingerslev, H.J. Stressful Life Events are Associated with a Poor in-Vitro Fertilization (IVF) Outcome: A Prospective Study. Hum. Reprod. 2009, 24, 2173–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Coussons-Read, M.E. Effects of Prenatal Stress on Pregnancy and Human Development: Mechanisms and Pathways. Obstet. Med. 2013, 6, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Iliadis, S.I.; Comasco, E.; Sylven, S.; Hellgren, C.; Sundstrom Poromaa, I.; Skalkidou, A. Prenatal and Postpartum Evening Salivary Cortisol Levels in Association with Peripartum Depressive Symptoms. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0135471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Federenko, I.S.; Wadhwa, P.D. Women’s Mental Health during Pregnancy Influences Fetal and Infant Developmental and Health Outcomes. CNS Spectr. 2004, 9, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guardino, C.M.; Schetter, C.D. Coping during Pregnancy: A Systematic Review and Recommendations. Health Psychol. Rev. 2014, 8, 70–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alvarenga, P.; Frizzo, G.B. Stressful Life Events and Women’s Mental Health during Pregnancy and Postpartum Period. Paid. Cad. Psicol. E Educ. 2017, 27, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, R.F.; Pineda, B.S.; Barrera, A.Z.; Bunge, E.; Leykin, Y. Digital Tools for Prevention and Treatment of Depression: Lessons from the Institute for International Internet Interventions for Health. Clin. Y Salud 2021, 32, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Assisted Reproduction Techniques (ART) | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 324) | No (n = 291) | Yes (n = 30) | ||

| Maternal age (years) | 34.0 [30.0; 36.0] | 34.0 [30.0; 36.0] | 35.0 [32.0; 38.0] | 0.028 |

| Marital status | 0.741 | |||

| Married | 212 (65.4%) | 191 (65.6%) | 21 (70.0%) | |

| Separated | 1 (0.3%) | 1 (0.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Single | 108 (33.3%) | 99 (34.1%) | 9 (30.0%) | |

| Education | 0.887 | |||

| Primary degree | 148 (45.7%) | 135 (46.4%) | 13 (43.3%) | |

| High School degree | 3 (0.9%) | 3 (1.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| University degree | 170 (52.5%) | 153 (52.6%) | 17 (56.7%) | |

| Country of birth | 0.313 | |||

| Spain | 292 (90.1%) | 266 (91.4%) | 26 (86.7%) | |

| Europe | 8 (2.5%) | 7 (2.4%) | 1 (3.3%) | |

| Latin America | 15 (4.6%) | 12 (4.1%) | 3 (10.0%) | |

| Other | 6 (1.9%) | 6 (2.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Employment | 0.318 | |||

| Employed | 238 (73.7%) | 213 (73.2%) | 25 (83.3%) | |

| Unemployed | 83 (25.6%) | 78 (26.9%) | 5 (16.7%) | |

| Comorbidities | 54 (16.7%) | 48 (16.6%) | 6 (20.0%) | 0.823 |

| First time of maternity | 153 (47.2%) | 133 (45.7%) | 20 (66.7%) | 0.046 |

| Abortions before | 57 (18.8%) | 52 (19.2%) | 5 (17.2%) | 0.996 |

| C-section before | 24 (7.5%) | 23 (8.0%) | 1 (3.3%) | 0.713 |

| PHQ-9 | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| <10 (n = 260) | ≥10 (n = 49) | ||

| Maternal age (years) | 33.0 [30.0; 36.0] | 35.0 [31.0; 36.0] | 0.218 |

| Marital status | 0.193 | ||

| Married | 176 (68.0%) | 28 (57.1%) | |

| Separated | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (2.0%) | |

| Single | 84 (32.3%) | 20 (40.8%) | |

| Education | 0.088 | ||

| Primary degree | 118 (45.4%) | 23 (46.9%) | |

| High School degree | 1 (0.4%) | 2 (4.1%) | |

| University degree | 141 (54.2%) | 24 (49.0%) | |

| Country of birth | 0.475 | ||

| Spain | 235 (90.4%) | 46 (93.9%) | |

| Europe | 9 (3.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Latin America | 10 (3.9%) | 3 (6.1%) | |

| Other | 6 (2.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Employment | 0.997 | ||

| Employed | 191 (73.5%) | 35 (72.9%) | |

| Unemployed | 69 (26.5%) | 14 (28.6%) | |

| Comorbidities | 41 (15.8%) | 10 (20.4%) | 0.561 |

| First time of maternity | 131 (50.4%) | 19 (38.8%) | 0.182 |

| Abortions before | 45 (18.4%) | 7 (15.9%) | 0.859 |

| C-section before | 17 (6.6%) | 4 (8.2%) | 0.757 |

| ART | 19 (67.9%) | 9 (32.1%) | 0.030 |

| Rho | p-Value | Rho | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAD-7 | 0.54 | <0.001 | PDPI-R-Self-esteem | −0.26 | <0.001 |

| Resilience | −0.33 | <0.001 | PDPI-R-Partner support | −0.16 | 0.004 |

| General concerns | 0.22 | <0.001 | PDPI-R-Family support | −0.18 | 0.002 |

| SLE | 0.35 | <0.001 | PDPI-R-Friends support | −0.20 | <0.001 |

| PDPI-R-SES | −0.14 | 0.012 | PDPI-R-Marital satisfaction | 0.03 | 0.572 |

| PDPI-R-Pregnancy intendedness | −0.08 | 0.173 | PDPI-R-Life stress | 0.17 | 0.003 |

| Model 1 | β ± SE | p-Value | Model 2 | β ± SE | p-Value | Model 3 | β ± SE | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ART | 6.75 ± 0.74 | <0.001 | ART | 9.60 ± 2.26 | <0.001 | ART | 16.51 ± 3.22 | <0.001 |

| Maternal age | −0.07 ± 0.06 | 0.211 | Marital status (Ref. Married) | 0.74 ± 0.41 | 0.072 | |||

| Marital status (Ref. Married) | 1.14 ± 0.50 | 0.022 | GAD−7 | 0.43± 0.06 | <0.001 | |||

| Education (Ref. University) | 0.10 ± 0.49 | 0.845 | Resilience | −0.05 ± 0.02 | 0.004 | |||

| Country of birth (Ref. Spain) | −1.05 ± 0.81 | 0.846 | Stressful life events | 0.17 ± 0.06 | 0.003 | |||

| Employment (Ref. Employed) | 0.35 ± 0.55 | 0.518 | General concerns | 0.12 ± 0.07 | 0.074 | |||

| Comorbidities | 0.09 ± 0.62 | 0.881 | PDPI-R-Socioeconomic status | 0.03 ± 0.36 | 0.931 | |||

| First time of maternity | −0.67 ± 0.54 | 0.215 | PDPI-R-Self-esteem | −1.21 ± 0.61 | 0.048 | |||

| Abortions before | −0.98 ± 0.66 | 0.139 | PDPI-R-Partner support | −1.50 ± 0.60 | 0.013 | |||

| C-section | 0.18 ± 1.02 | 0.863 | PDPI-R-Family support | −0.23 ± 0.39 | 0.556 | |||

| PDPI-R-Friends support | 0.01 ± 0.27 | 0.963 | ||||||

| PDPI-R-Life stress | 0.06 ± 0.21 | 0.777 | ||||||

| R2 = 0.02 | R2 = 0.20 | R2 = 0.60 |

| Model in ART Subset | β ± SE | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Marital status (Ref. Married) | −0.66 ± 2.67 | 0.810 |

| Resilience | −0.02 ± 0.11 | 0.840 |

| Stressful life events | 0.30 ± 0.25 | 0.258 |

| General concerns | −0.03 ± 0.38 | 0.939 |

| PDPI-R-Socioeconomic status | −2.80 ± 2.50 | 0.288 |

| PDPI-R-Self-esteem | 1.79 ± 4.71 | 0.713 |

| PDPI-R-Partner support | −3.51 ± 3.51 | 0.341 |

| PDPI-R-Family support | −3.01 ± 2.75 | 0.299 |

| PDPI-R-Friends support | 2.46 ± 2.03 | 0.253 |

| PDPI-R-Life stress | −0.27 ± 1.50 | 0.863 |

| R2 = 0.35 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ramiro-Cortijo, D.; Soto-Balbuena, C.; Rodríguez-Muñoz, M.F. Early Association Factors for Depression Symptoms in Pregnancy: A Comparison between Spanish Women Spontaneously Gestation and with Assisted Reproduction Techniques. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 5672. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10235672

Ramiro-Cortijo D, Soto-Balbuena C, Rodríguez-Muñoz MF. Early Association Factors for Depression Symptoms in Pregnancy: A Comparison between Spanish Women Spontaneously Gestation and with Assisted Reproduction Techniques. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2021; 10(23):5672. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10235672

Chicago/Turabian StyleRamiro-Cortijo, David, Cristina Soto-Balbuena, and María F. Rodríguez-Muñoz. 2021. "Early Association Factors for Depression Symptoms in Pregnancy: A Comparison between Spanish Women Spontaneously Gestation and with Assisted Reproduction Techniques" Journal of Clinical Medicine 10, no. 23: 5672. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10235672