Accuracy of Dynamic Computer-Assisted Implant Placement: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Clinical and In Vitro Studies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. PICO Questions

- (P) Population in vivo: Edentulous and partially edentulous patients who require an implant-prosthetic restoration;

- (P) Population in vitro: Plastic models of edentulous or partially edentulous jaws;

- (I) Intervention: Implant placement with a dynamic computer-assisted surgical procedure;

- (C) Comparison: Results of the clinical and in vitro investigations; and

- (O) Outcome Acccuracy: Deviation between the planned and actual achieved implant position.

2.3. Search Strategy

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Risk of Bias, Quality Assessment, and Interstudy Heterogeneity

2.6. Data Extraction and Method of Analysis

3. Results

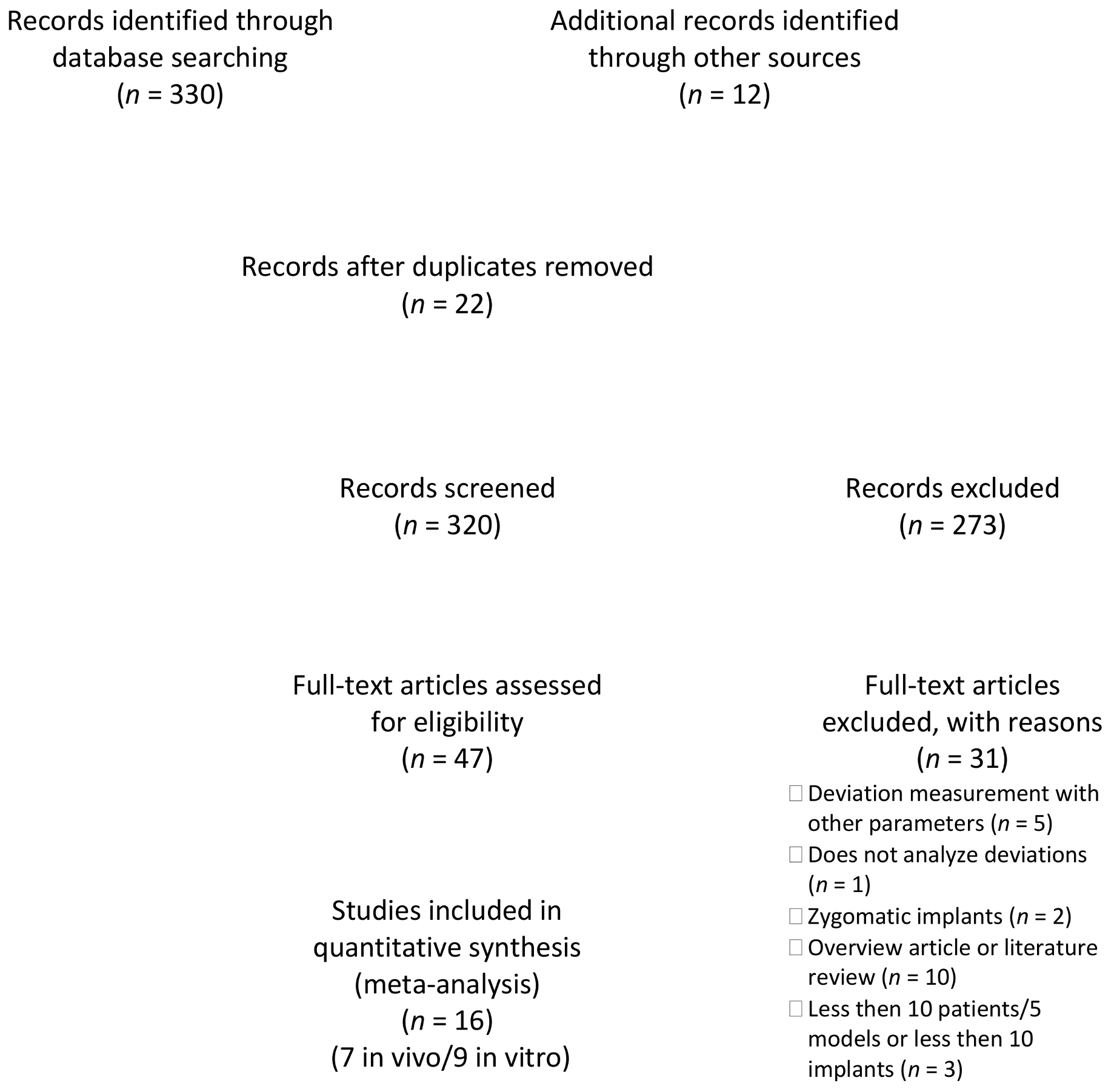

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Quality of the Studies

3.3. Outcomes

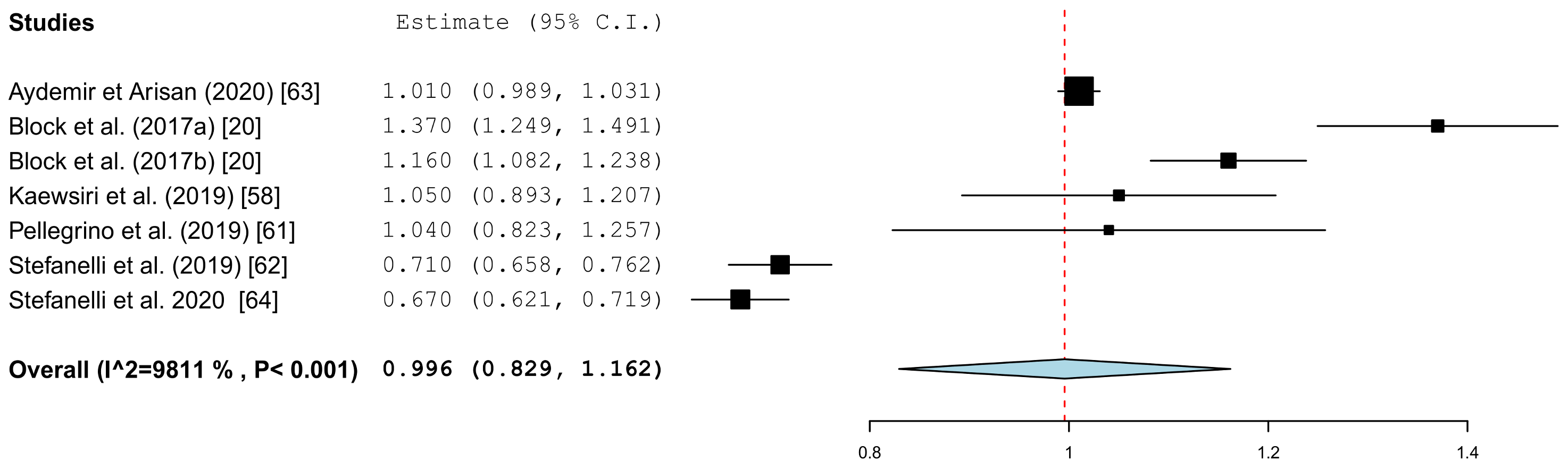

3.3.1. Coronal Deviation

3.3.2. Apical Deviation

3.3.3. Angle Deviation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- D’Haese, J.; Ackhurst, J.; Wismeijer, D.; De Bruyn, H.; Tahmaseb, A. Current state of the art of computer-guided implant surgery. Periodontology 2000 2017, 73, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garber, D.A.; Belser, U.C. Restoration-driven implant placement with restoration-generated site development. Compend. Contin. Educ. Dent. 1995, 16, 796, 798–802, 804. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Albrektsson, T.; Chrcanovic, B.; Ostman, P.O.; Sennerby, L. Initial and long-term crestal bone responses to modern dental implants. Periodontology 2000 2017, 73, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romanos, G.E.; Delgado-Ruiz, R.; Sculean, A. Concepts for prevention of complications in implant therapy. Periodontology 2000 2019, 81, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Amri, M.D. Influence of interimplant distance on the crestal bone height around dental implants: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2016, 115, 278–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staubli, N.; Walter, C.; Schmidt, J.C.; Weiger, R.; Zitzmann, N.U. Excess cement and the risk of peri-implant disease—A systematic review. Clin. Oral. Implant. Res. 2017, 28, 1278–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosshardt, D.D.; Chappuis, V.; Buser, D. Osseointegration of titanium, titanium alloy and zirconia dental implants: Current knowledge and open questions. Periodontology 2000 2017, 73, 22–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wismeijer, D.; Joda, T.; Flugge, T.; Fokas, G.; Tahmaseb, A.; Bechelli, D.; Bohner, L.; Bornstein, M.; Burgoyne, A.; Caram, S.; et al. Group 5 ITI consensus report: Digital technologies. Clin. Oral. Implant. Res. 2018, 29 (Suppl. 16), 436–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Yafi, F.; Camenisch, B.; Al-Sabbagh, M. Is digital guided implant surgery accurate and reliable? Dent. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 63, 381–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahmaseb, A.; Wu, V.; Wismeijer, D.; Coucke, W.; Evans, C. The accuracy of static computer-aided implant surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Oral. Implant. Res. 2018, 29 (Suppl. 16), 416–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargallo-Albiol, J.; Barootchi, S.; Salomo-Coll, O.; Wang, H.L. Advantages and disadvantages of implant navigation surgery. A systematic review. Ann. Anat. 2019, 225, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abduo, J.; Lau, D. Accuracy of static computer-assisted implant placement in anterior and posterior sites by clinicians new to implant dentistry: In vitro comparison of fully guided, pilot-guided, and freehand protocols. Int. J. Implant. Dent. 2020, 6, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahmaseb, A.; Wismeijer, D.; Coucke, W.; Derksen, W. Computer technology applications in surgical implant dentistry: A systematic review. Int. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Implant. 2014, 29, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raico Gallardo, Y.N.; da Silva-Olivio, I.R.T.; Mukai, E.; Morimoto, S.; Sesma, N.; Cordaro, L. Accuracy comparison of guided surgery for dental implants according to the tissue of support: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Oral. Implant. Res. 2017, 28, 602–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnutenhaus, S.; Edelmann, C.; Rudolph, H.; Luthardt, R.G. Retrospective study to determine the accuracy of template-guided implant placement using a novel nonradiologic evaluation method. Oral. Surg. Oral. Med. Oral. Pathol. Oral. Radiol. 2016, 121, e72–e79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.H.; Cao, C.R.; Lin, W.C.; Shu, C.M. Experimental and numerical simulation study of the thermal hazards of four azo compounds. J. Hazard Mater. 2019, 365, 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Wangrao, K.; Liu, L.; Liu, L.; Yao, Y. Quantification of image artifacts from navigation markers in dynamic guided implant surgery and the effect on registration performance in different clinical scenarios. Int. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Implant. 2019, 34, 726–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vercruyssen, M.; Fortin, T.; Widmann, G.; Jacobs, R.; Quirynen, M. Different techniques of static/dynamic guided implant surgery: Modalities and indications. Periodontology 2000 2014, 66, 214–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gambarini, G.; Galli, M.; Stefanelli, L.V.; Di Nardo, D.; Morese, A.; Seracchiani, M.; De Angelis, F.; Di Carlo, S.; Testarelli, L. Endodontic microsurgery using dynamic navigation system: A case report. J. Endod. 2019, 45, 1397–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brief, J.; Edinger, D.; Hassfeld, S.; Eggers, G. Accuracy of image-guided implantology. Clin. Oral. Implant. Res. 2005, 16, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, J.; Westendorff, C.; Gomez-Roman, G.; Reinert, S. Accuracy of navigation-guided socket drilling before implant installation compared to the conventional free-hand method in a synthetic edentulous lower jaw model. Clin. Oral. Implant. Res. 2005, 16, 609–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, F.J.; Baethge, C.; Swennen, G.; Rosahl, S. Navigated vs. conventional implant insertion for maxillary single tooth replacement. Clin. Oral. Implant. Res. 2005, 16, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.T. A novel application of dynamic navigation system in socket shield technique. J. Oral. Implantol. 2019, 45, 409–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Block, M.S.; Emery, R.W. Static or dynamic navigation for implant placement-choosing the method of guidance. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2016, 74, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayoub, A.; Pulijala, Y. The application of virtual reality and augmented reality in oral & maxillofacial surgery. BMC Oral. Health 2019, 19, 238. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; The PRISMA Group. Reprint—Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Phys. Ther. 2009, 89, 873–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito, M.; Coulthard, P.; Worthington, H.V.; Jokstad, A. Quality assessment of randomized controlled trials of oral implants. Int. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Implant. 2001, 16, 783–792. [Google Scholar]

- Gaggl, A.; Schultes, G.; Karcher, H. Navigational precision of drilling tools preventing damage to the mandibular canal. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2001, 29, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.; Gu, L.; Wu, Z.; Huang, Y.; Kang, L. The implementation of an integrated computer-aided system for dental implantology. Ann. Int. Conf. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. 2008, 2008, 58–61. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.T.; Chiu, Y.W.; Peng, C.Y. Preservation of inferior alveolar nerve using the dynamic dental implant navigation system. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 78, 678–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wittwer, G.; Adeyemo, W.L.; Schicho, K.; Gigovic, N.; Turhani, D.; Enislidis, G. Computer-guided flapless transmucosal implant placement in the mandible: A new combination of two innovative techniques. Oral. Surg. Oral. Med. Oral. Pathol. Oral. Radiol. Endod. 2006, 101, 718–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, W.; Fan, S.; Wang, F.; Huang, W.; Jamjoom, F.Z.; Wu, Y. A novel extraoral registration method for a dynamic navigation system guiding zygomatic implant placement in patients with maxillectomy defects. Int. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schramm, A.; Gellrich, N.C.; Schimming, R.; Schmelzeisen, R. Computer-assisted insertion of zygomatic implants (Branemark system) after extensive tumor surgery. Mund Kiefer. Gesichtschir. 2000, 4, 292–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wittwer, G.; Adeyemo, W.L.; Wagner, A.; Enislidis, G. Computer-guided flapless placement and immediate loading of four conical screw-type implants in the edentulous mandible. Clin. Oral. Implant. Res. 2007, 18, 534–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdougo, M.; Fortin, T.; Blanchet, E.; Isidori, M.; Bosson, J.L. Flapless implant surgery using an image-guided system. A 1- to 4-year retrospective multicenter comparative clinical study. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res. 2010, 12, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanschitz, F.; Birkfellner, W.; Watzinger, F.; Schopper, C.; Patruta, S.; Kainberger, F.; Figl, M.; Kettenbach, J.; Bergmann, H.; Ewers, R. Evaluation of accuracy of computer-aided intraoperative positioning of endosseous oral implants in the edentulous mandible. Clin. Oral. Implant. Res. 2002, 13, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golob Deeb, J.; Bencharit, S.; Carrico, C.K.; Lukic, M.; Hawkins, D.; Rener-Sitar, K.; Deeb, G.R. Exploring training dental implant placement using computer-guided implant navigation system for predoctoral students: A pilot study. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2019, 23, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essig, H.; Rana, M.; Kokemueller, H.; Zizelmann, C.; von See, C.; Ruecker, M.; Tavassol, F.; Gellrich, N.C. Referencing of markerless CT data sets with cone beam subvolume including registration markers to ease computer-assisted surgery—A clinical and technical research. Int. J. Med. Robot 2013, 9, e39–e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, C.R.; Murphy, R.J.; Coon, D.; Basafa, E.; Otake, Y.; Al Rakan, M.; Rada, E.; Susarla, S.; Swanson, E.; Fishman, E.; et al. Preliminary development of a workstation for craniomaxillofacial surgical procedures: Introducing a computer-assisted planning and execution system. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2014, 25, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widmann, G.; Stoffner, R.; Keiler, M.; Zangerl, A.; Widmann, R.; Puelacher, W.; Bale, R. A laboratory training and evaluation technique for computer-aided oral implant surgery. Int. J. Med. Robot 2009, 5, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Lin, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wang, C. Real-time motion tracking in image-guided oral implantology. Int. J. Med. Robot 2008, 4, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hultin, M.; Svensson, K.G.; Trulsson, M. Clinical advantages of computer-guided implant placement: A systematic review. Clin. Oral. Implant. Res. 2012, 23 (Suppl. 6), 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, M.S. Static and dynamic navigation for dental implant placement. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2016, 74, 231–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquardt, P.; Witkowski, S.; Strub, J. Three-dimensional navigation in implant dentistry. Eur. J. Esthet. Dent. 2007, 2, 80–98. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Block, M.S. Accuracy using static or dynamic navigation. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2016, 74, 2–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brignardello-Petersen, R. Similar deviation between planned and placed implants when using static and dynamic computer-assisted systems in single-tooth implants. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2019, 150, e171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azari, A.; Nikzad, S. Computer-assisted implantology: Historical background and potential outcomes—A review. Int. J. Med. Robot 2008, 4, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.J.; Bier, J. Surgical navigation in oral implantology. Implant Dent. 2006, 15, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, A.; Wanschitz, F.; Birkfellner, W.; Zauza, K.; Klug, C.; Schicho, K.; Kainberger, F.; Czerny, C.; Bergmann, H.; Ewers, R. Computer-aided placement of endosseous oral implants in patients after ablative tumour surgery: Assessment of accuracy. Clin. Oral. Implant. Res. 2003, 14, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herklotz, I.; Beuer, F.; Kunz, A.; Hildebrand, D.; Happe, A. Navigation in implantology. Int. J. Comput. Dent. 2017, 20, 9–19. [Google Scholar]

- Somogyi-Ganss, E.; Holmes, H.I.; Jokstad, A. Accuracy of a novel prototype dynamic computer-assisted surgery system. Clin. Oral. Implant. Res. 2015, 26, 882–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.G.; Lee, W.J.; Lee, S.S.; Heo, M.S.; Huh, K.H.; Choi, S.C.; Kim, T.I.; Yi, W.J. An advanced navigational surgery system for dental implants completed in a single visit: An in vitro study. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2015, 43, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emery, R.W.; Merritt, S.A.; Lank, K.; Gibbs, J.D. Accuracy of dynamic navigation for dental implant placement-model-based evaluation. J. Oral. Implantol. 2016, 42, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mediavilla Guzman, A.; Riad Deglow, E.; Zubizarreta-Macho, A.; Agustin-Panadero, R.; Hernandez Montero, S. Accuracy of computer-aided dynamic navigation compared to computer-aided static navigation for dental implant placement: An in vitro study. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorba-Garcia, A.; Figueiredo, R.; Gonzalez-Barnadas, A.; Camps-Font, O.; Valmaseda-Castellon, E. Accuracy and the role of experience in dynamic computer guided dental implant surgery: An in-vitro study. Med. Oral. Patol. Oral. Cir. Bucal. 2019, 24, e76–e83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellegrino, G.; Bellini, P.; Cavallini, P.F.; Ferri, A.; Zacchino, A.; Taraschi, V.; Marchetti, C.; Consolo, U. Dynamic navigation in dental implantology: The influence of surgical experience on implant placement accuracy and operating time. An in vitro study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.H.; Lee, J.W.; Lim, S.H.; Kim, Y.H.; Kim, M.K. Verification of the usability of a navigation method in dental implant surgery: In vitro comparison with the stereolithographic surgical guide template method. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2014, 42, 1530–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaewsiri, D.; Panmekiate, S.; Subbalekha, K.; Mattheos, N.; Pimkhaokham, A. The accuracy of static vs. dynamic computer-assisted implant surgery in single tooth space: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Oral. Implant. Res. 2019, 30, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Block, M.S.; Emery, R.W.; Lank, K.; Ryan, J. Implant placement accuracy using dynamic navigation. Int. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Implant. 2017, 32, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, M.S.; Emery, R.W.; Cullum, D.R.; Sheikh, A. Implant placement is more accurate using dynamic navigation. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 75, 1377–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, G.; Taraschi, V.; Andrea, Z.; Ferri, A.; Marchetti, C. Dynamic navigation: A prospective clinical trial to evaluate the accuracy of implant placement. Int. J. Comput. Dent. 2019, 22, 139–147. [Google Scholar]

- Stefanelli, L.V.; DeGroot, B.S.; Lipton, D.I.; Mandelaris, G.A. Accuracy of a dynamic dental implant navigation system in a private practice. Int. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Implant. 2019, 34, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aydemir, C.A.; Arisan, V. Accuracy of dental implant placement via dynamic navigation or the freehand method: A split-mouth randomized controlled clinical trial. Clin. Oral. Implant. Res. 2020, 31, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefanelli, L.V.; Mandelaris, G.A.; DeGroot, B.S.; Gambarini, G.; De Angelis, F.; Di Carlo, S. Accuracy of a novel trace-registration method for dynamic navigation surgery. Int. J. Periodontics Restor. Dent. 2020, 40, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bover-Ramos, F.; Vina-Almunia, J.; Cervera-Ballester, J.; Penarrocha-Diago, M.; Garcia-Mira, B. Accuracy of Implant placement with computer-guided surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis comparing cadaver, clinical, and in vitro studies. Int. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Implant. 2018, 33, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vercruyssen, M.; Cox, C.; Coucke, W.; Naert, I.; Jacobs, R.; Quirynen, M. A randomized clinical trial comparing guided implant surgery (bone- or mucosa-supported) with mental navigation or the use of a pilot-drill template. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2014, 41, 717–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, R.E.; Schneider, D.; Ganeles, J.; Wismeijer, D.; Zwahlen, M.; Hammerle, C.H.; Tahmaseb, A. Computer technology applications in surgical implant dentistry: A systematic review. Int. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Implant. 2009, 24, 92–109. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, D.; Marquardt, P.; Zwahlen, M.; Jung, R.E. A systematic review on the accuracy and the clinical outcome of computer-guided template-based implant dentistry. Clin. Oral. Implant. Res. 2009, 20 (Suppl. 4), 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omori, Y.; Lang, N.P.; Botticelli, D.; Papageorgiou, S.N.; Baba, S. Biological and mechanical complications of angulated abutments connected to fixed dental prostheses: A systematic review with meta-analysis. J. Oral. Rehabil. 2020, 47, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forna, N.; Agop-Forna, D. Esthetic aspects in implant-prosthetic rehabilitation. Med. Pharm. Rep. 2019, 92, S6–S13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickenig, H.J.; Eitner, S.; Rothamel, D.; Wichmann, M.; Zoller, J.E. Possibilities and limitations of implant placement by virtual planning data and surgical guide templates. Int. J. Comput. Dent. 2012, 15, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Soares, M.M.; Harari, N.D.; Cardoso, E.S.; Manso, M.C.; Conz, M.B.; Vidigal, G.M., Jr. An in vitro model to evaluate the accuracy of guided surgery systems. Int. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Implant. 2012, 27, 824–831. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sicilia, A.; Botticelli, D.; Working, G. Computer-guided implant therapy and soft- and hard-tissue aspects. The Third EAO Consensus Conference 2012. Clin. Oral. Implant. Res. 2012, 23 (Suppl. 6), 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Hwang, C.J.; Choi, Y.J.; Houschyar, K.S.; Yu, J.H.; Bae, S.Y.; Cha, J.Y. Registration of digital dental models and cone-beam computed tomography images using 3-dimensional planning software: Comparison of the accuracy according to scanning methods and software. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofacial. Orthop. 2020, 157, 843–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Clinical Studies | In Vitro Studies | |

|---|---|---|

| Inclusion criteria |

|

|

| Exclusion criteria |

|

|

| Study | Number of Models | Number of Implants | Edentulism | Jaw | Implant System | Guide System | Planning Software |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brief et al. (2005) [20] (Robo) | 5 | 15 | Partially | Mandible | NR | RoboDent; RoboDent, GmbH, Berlin, Germany | RoboDent; RoboDent, GmbH, Berlin, Germany |

| Brief et al. (2005) (IGI) [20] | 5 | 15 | Partially | Mandible | NR | IGI DenX; Denx Ltd., Moshav Ora, Jerusalem, Israel | IGI DenX; Denx Ltd., Moshav Ora, Jerusalem, Israel |

| Emery et al. (2016) [53] | 27 | 47 | Partially and fully edentulous | Maxilla and mandible | Zimmer/Biomet 3i, Palm Beach, FL, USA | X-Guide; X-Nav Technologies, LLC, Lansdale, PA, USA | X-Guide; X-Nav Technologies, LLC, Lansdale, PA, USA |

| Hoffmann et al. (2005) [21] | 16 | 112 | Fully edentulous | Mandible | NR | Vector-Vision Compact; VVC, BrainLAB, Heimstetten, Germany | NR |

| Kang et al. (2014) (molar) [57] | 10 | 20 | Fully edentulous | Mandible molar region | Dentium implant Fx4314; Dentium, Seoul, Korea | CBYON suite system; CBYON Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA | SimPlant; Materialise Dental, Leuven, Belgium |

| Kang et al. (2014) (canine) [57] | 10 | 20 | Fully edentulous | Mandible canine region | Dentium implant Fx4314; Dentium, Seoul, Korea | CBYON suite system; CBYON Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA | SimPlant; Materialise Dental, Leuven, Belgium |

| Kim et al. (2015) [52] | 10 | 110 | Partially | Maxilla and mandible | Ostem TS; Osstem Implant, Seoul, Korea | Polaris Vicar; Northern Digital Inc., Waterloo, ON, Canada | InVivoDental; Anatomage, San Jose, CA, USA |

| Mediavilla-Guzmán et al. (2019) [54] | 10 | 20 | Partially | Maxilla | BioHorizons, Birmingham, AL, USA | Navident System; ClaroNav Inc., Toronto, ON, Canada | Navident System; ClaroNav Inc., Toronto, ON, Canada |

| Jorba-García et al. (2019) [55] | 6 | 18 | Partially | Mandible | Ticare In-Hex; MG Mozo-Grau, Valladolid, Spain | Navident System; ClaroNav Inc., Toronto, ON, Canada | Navident System; ClaroNav Inc., Toronto, ON, Canada |

| Pellegrino et al. (2020) [56] | 16 | 112 | Edentulous | Maxilla | Southern Implants, Irene, South Africa | ImplaNav; BresMedical, Sydney, Australia | ImplaNav; BresMedical, Sydney, Australia |

| Somogyi-Ganss et al. (2015) [51] | 10 | 80 | Partially | Maxilla and mandible | NR | Prototype Navident; Claron Technology Inc., Toronto, ON, Canada | Prototype Navident; Claron Technology Inc., Toronto, ON, Canada |

| Study | Design | Number of Patients | Number of Implants | Edentulism | Jaw | Implant System | Guide System | Planning Software |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aydemir and Arisan (2020) [63] | Prospective | 30 | 43 | Partially | Maxilla | Southern Implants, Irene, South Africa | Navident System; ClaroNav Inc., Toronto, ON, Canada | Navident System; ClaroNav Inc., Toronto, ON, Canada |

| Block et al. (2017a) [59] | Prospective | 80 | 80 | Partially | Maxilla and mandible | NR | X-Guide; X-Nav Technologies, LLC, Lansdale, PA, USA | X-Guide; X-Nav Technologies, LLC, Lansdale, PA, USA |

| Block et al. (2017b) [60] | Prospective | NR (but more than 10) | 219 | Partially | Maxilla and mandible | NR | X-Guide; X-Nav Technologies, LLC, Lansdale, PA, USA | X-Guide; X-Nav Technologies, LLC, Lansdale, PA, USA |

| Kaewsiri et al. (2019) [58] | Prospective | 30 | 30 | Partially | Maxilla and mandible | Straumann Bone level (18), Straumann Bone Level Taper (9), Straumann Tissue level (3) | IRIS-100; EPED Inc., Kaohsiung City, Taiwan | IRIS-100; EPED Inc., Kaohsiung City, Taiwan |

| Pellegrino et al. (2019) [61] | Prospective | 10 | 18 | Partially and fully edentulous | Maxilla and mandible | Southern Implants IBT (16), Co-axis (2), Southern Implants, Irene, South Africa | ImplaNav; BresMedical, Sydney, Australia | ImplaNav; BresMedical, Sydney, Australia |

| Stefanelli et al. (2019) [62] | Retrospective | 89 | 231 | Partially and fully edentulous | Maxilla and mandible | NR | Navident System; ClaroNav Inc., Toronto, ON, Canada | Navident System; ClaroNav Inc., Toronto, ON, Canada |

| Stefanelli et al. (2020) [64] | Retrospective | 59 | 136 | Partially | Maxilla and mandible | Osseotite Tapered, Zimmer/Biomet 3i, Palm Beach, FL, USA | Navident System; ClaroNav Inc., Toronto, ON, Canada | Navident System; ClaroNav Inc., Toronto, ON, Canada |

| Study | Year | Number of Patients | Number of Implants | Angle Deviation | SD | 95% CI | Global Deviation at the Implant Platform | SD | 95% CI | Linear Lateral Deviation at the Implant Platform | SD | 95% CI | Vertical Deviation at the Implant Platform | SD | 95% CI | Global Deviation at the Apex | SD | 95% CI | Linear Lateral Deviation at the Apex | SD | 95% CI | Vertical Deviation at the Apex | SD | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aydemir and Arisan [63] | 2020 | 30 | 43 | 5.59 | 0.39 | 4.87–6.42 | 1.01 | 0.07 | 0.87–1.18 | 1.83 | 0.12 | 1.60–2.10 | ||||||||||||

| Block et al. [59] | 2017a | 80 | 80 | 3.62 | 2.73 | 1.37 | 0.55 | 0.87 | 0.42 | 0.93 | 0.60 | 1.56 | 0.69 | 1.09 | 0.66 | 0.96 | 0.66 | |||||||

| Block et al. [60] | 2017b | NA > 10 | 219 | 2.97 | 2.09 | 2.46–3.44 | 1.16 | 0.59 | 1.03–1.27 | 0.74 | 0.43 | 0.60–0.78 | 0.76 | 0.60 | 0.68–0.94 | 1.29 | 0.65 | 1.14–1.43 | 0.9 | 0.55 | 0.73–0.99 | 0.78 | 0.6 | 0.68–0.94 |

| Kaewsiri et al. [58] | 2019 | 30 | 30 | 3.06 | 1.37 | 2.54–3.57 | 1.05 | 0.44 | 0.89–1.21 | 1.29 | 0.5 | 1.10–1.48 | ||||||||||||

| Pellegrino et al. [61] | 2019 | 10 | 18 | 6.46 | 3.95 | 1.04 | 0.47 | 0.43 | 0.34 | 1.35 | 0.56 | |||||||||||||

| Stefanelli et al. [62] | 2019 | 89 | 231 | 2.26 | 1.62 | 0.71 | 0.40 | 1.00 | 0.49 | |||||||||||||||

| Stefanelli et al. [64] | 2020 | 59 | 136 | 2.50 | 1.04 | 0.67 | 0.29 | 0.99 | 0.33 | 0.55 | 0.25 |

| Study | Year | Number of Models | Number of Implants | Angle Deviation | SD | Global Deviation at the Implant Platform | SD | Linear Lateral Deviation at the Implant Platform | SD | Vertical Deviation at the Implant Platform | SD | Global Deviation at the Apex | SD | Linear Lateral Deviation at the Apex | SD | Vertical Deviation at the Apex | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brief et al. [20] | 2005 (RoBo) | 5 | 15 | 2.12 | 0.78 | 0.35 | 0.17 | 0.60 | 0.20 | 0.47 | 0.18 | 0.32 | 0.21 | ||||

| Brief et al. [20] | 2005 (IGI) | 5 | 15 | 4.21 | 4.76 | 0.65 | 0.58 | 0.94 | 0.40 | 0.68 | 0.31 | 0.61 | 0.36 | ||||

| Emery et al. [53] | 2016 | 27 | 47 | 1.09 | 0.55 | 0.46 | 0.20 | 0.33 | 0.19 | 0.26 | 0.19 | 0.48 | 0.21 | 0.36 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.19 |

| Hoffmann et al. [21] | 2005 | 16 | 112 | 4.20 | 1.80 | ||||||||||||

| Jorba-García et al. [55] | 2019 | 6 | 18 | 1.60 | 1.30 | 1.29 | 0.46 | 0.85 | 0.41 | 1.33 | 0.50 | 0.88 | 0.47 | ||||

| Kang et al. [57] | 2014 (molar) | 10 | 20 | 8.97 | 3.83 | 3.03 | 1.81 | 0.76 | 0.84 | 2.76 | 1.03 | 1.96 | 0.93 | ||||

| Kang et al. [57] | 2014 (canine) | 10 | 20 | 12.37 | 4.18 | 2.06 | 1.43 | 1.14 | 1.25 | 3.31 | 2.07 | 1.42 | 1.01 | ||||

| Kim et al. [52] | 2015 | 10 | 110 | 2.64 | 1.31 | 0.41 | 0.12 | 0.56 | 0.14 | ||||||||

| Mediavilla-Guzmán et al. [54] | 2019 | 10 | 20 | 4.00 | 1.41 | 0.85 | 0.48 | 1.18 | 0.60 | ||||||||

| Pelleriono et al. [56] | 2020 | 16 | 112 | 4.24 | 2.52 | 1.58 | 0.80 | 0.75 | 0.74 | 1.61 | 0.75 | 0.70 | 0.67 | ||||

| Somogyi-Ganss et al. [51] | 2015 | 10 | 80 | 2.99 | 1.68 | 1.14 | 0.55 | 1.71 | 0.61 | 1.18 | 0.56 | 1.04 | 0.71 |

| Study | Angle Deviation | Global Coronal Deviation | Global Apical Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Mean | Mean | |

| Dynamic navigation in vitro | 4.1° | 1.03 mm | 1.04 mm |

| Dynamic navigation clinical | 3.7° | 1.00 mm | 1.33 mm |

| Static navigation—clinical review 1 [65] | 3.6° | 1.10 mm | 1.40 mm |

| Static navigation—clinical review 2 [10] | 3.5° | 1.2 mm | 1.40 mm |

| Freehand implant placement [66] | 9.9° | 2.77 mm | 2.91 mm |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schnutenhaus, S.; Edelmann, C.; Knipper, A.; Luthardt, R.G. Accuracy of Dynamic Computer-Assisted Implant Placement: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Clinical and In Vitro Studies. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 704. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10040704

Schnutenhaus S, Edelmann C, Knipper A, Luthardt RG. Accuracy of Dynamic Computer-Assisted Implant Placement: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Clinical and In Vitro Studies. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2021; 10(4):704. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10040704

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchnutenhaus, Sigmar, Cornelia Edelmann, Anne Knipper, and Ralph G. Luthardt. 2021. "Accuracy of Dynamic Computer-Assisted Implant Placement: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Clinical and In Vitro Studies" Journal of Clinical Medicine 10, no. 4: 704. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10040704

APA StyleSchnutenhaus, S., Edelmann, C., Knipper, A., & Luthardt, R. G. (2021). Accuracy of Dynamic Computer-Assisted Implant Placement: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Clinical and In Vitro Studies. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(4), 704. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10040704