Association of Self-Reported Functional Limitations among a National Community-Based Sample of Older United States Adults with Pain: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Study Data

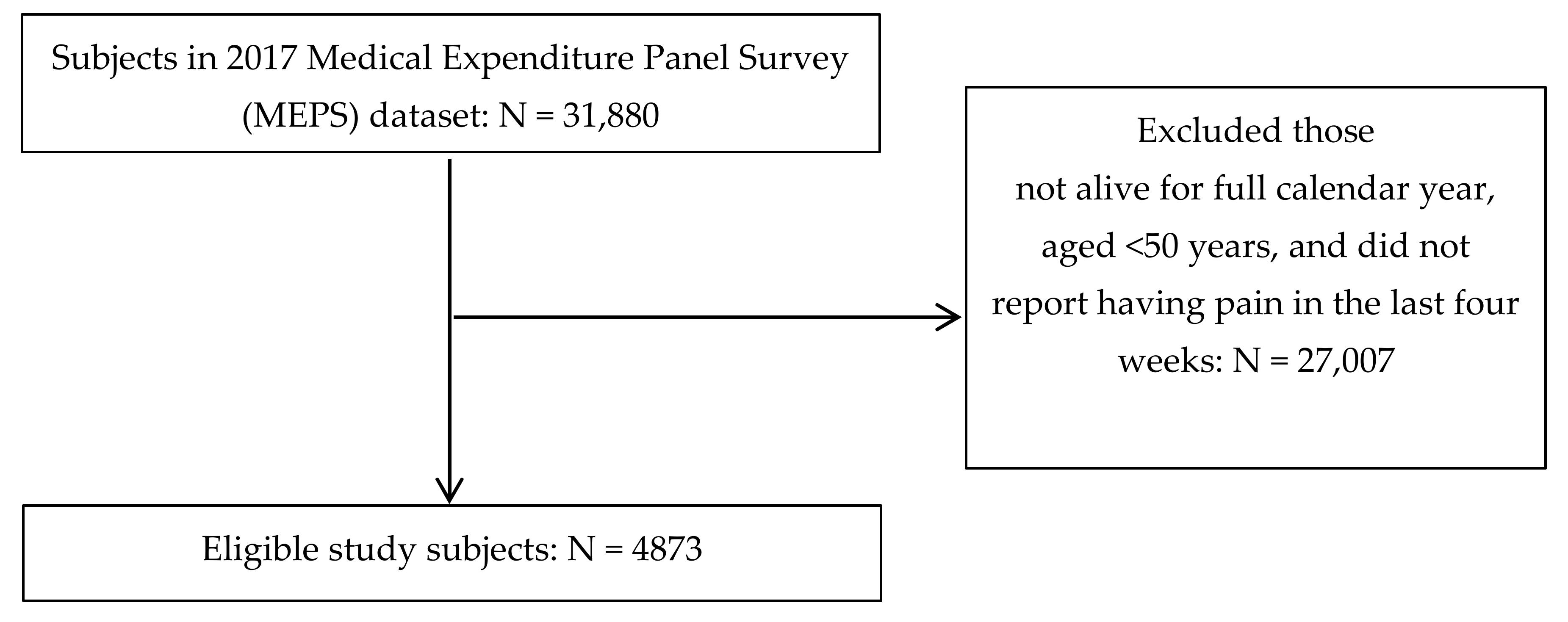

2.2. Study Eligibility

2.3. Independent Variables

2.4. Outcome Variable

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nahin, R.L. Estimates of pain prevalence and severity in adults: United States, 2012. J. Pain 2015, 16, 769–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Axon, D.R.; Patel, M.J.; Martin, J.R.; Slack, M.K. Use of multidomain management strategies by community dwelling adults with chronic pain: Evidence from a systematic review. Scand. J. Pain 2019, 19, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stamm, T.A.; Pieber, K.; Crevenna, R.; Dorner, T.E. Impairment in the activities of daily living in older adults with and without osteoporosis, osteoarthritis and chronic back pain: A secondary analysis of population-based health survey data. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016, 17, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Makris, U.E.; Fraenkel, L.; Han, L.; Leo-Summers, L.; Gill, T.M. Restricting back pain and subsequent mobility disability in community-living older persons. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2014, 62, 2142–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valderrama-Hinds, L.M.; Snih, S.A.; Rodriguez, M.A.; Wong, R. Association of arthritis and vitamin D insufficiency with physical disability in Mexican older adults—Findings from the Mexican Health and Aging Study. Rheumatol. Int. 2017, 37, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Eggermont, L.H.P.; Leveille, S.G.; Shi, L.; Kiely, D.K.; Shmerling, R.H.; Jones, R.N.; Guralnik, J.M.; Bean, J.F. Pain characteristics associated with the onset of disability in older adults: The maintenance of balance, independent living, intellect, and zest in the elderly Boston study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2014, 62, 1007–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Download Data Files, Documentation, and Codebooks. Available online: https://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_stats/download_data_files.jsp (accessed on 9 May 2020).

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Survey Background. Available online: https://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/about_meps/survey_back.jsp (accessed on 9 May 2020).

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: MEPS HC-201 2017 Full Year Consolidated Data File. Available online: https://meps.ahrq.gov/data_stats/download_data/pufs/h201/h201doc.pdf (accessed on 9 May 2020).

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. MEPS HC-201 2017 Full Year Consolidated Data Codebook. Available online: https://meps.ahrq.gov/data_stats/download_data/pufs/h201/h201cb.pdf (accessed on 9 May 2020).

- Andersen, R.M. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: Does it matter? J. Health Soc. Behav. 1995, 36, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zelaya, C.E.; Dahlhamer, J.M.; Lucas, J.W.; Conner, E.M. Chronic Pain and High-Impact Chronic Pain among U.S. Adults. 2019. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db390-H.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2020).

- Vaughn, I.A.; Terry, E.L.; Bartley, E.J.; Schaefer, N.S.; Fillingim, R.B. Racial-ethnic differences in osteoarthritis pain and disability: A meta-analysis. J. Pain 2019, 20, 629–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meints, S.M.; Miller, M.M.; Hirsh, A.T. Differences in pain coping between black and white Americans: A meta-analysis. J. Pain 2016, 17, 642–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mossey, J.M. Defining racial and ethnic disparities in pain management. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2011, 469, 1859–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tonelli, S.M.; Rakel, B.A.; Cooper, N.A.; Angstom, W.L.; Sluka, K.A. Women with knee osteoarthritis have more pain and poorer function than men, but similar physical activity prior to total knee replacement. Biol. Sex Differ. 2011, 2, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Makris, U.E.; Fraenkel, L.; Han, L.; Leo-Summers, L.; Gill, T.M. Epidemiology of restricting back pain in community-living older persons. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2011, 59, 610–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Roseen, E.J.; LaValley, M.P.; Li, S.; Saper, R.B.; Felson, D.T.; Fredman, L. Association of back pain with all-cause and cause-specific mortality among older women: A cohort study. J. Gen. Intern Med. 2019, 34, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Special Committee on Aging United States Senate. Aging Workforce Report. Available online: https://www.aging.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Aging%20Workforce%20Report%20FINAL.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2020).

- He, W.; Larsen, L.J. Older Americans with a Disability: 2008−2012: American Community Survey Reports. Available online: https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/2014/acs/acs-29.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2020).

- Alcaraz, K.I.; Eddens, K.S.; Blase, J.L.; Diver, W.R.; Patel, A.V.; Teras, L.R.; Stevens, V.L.; Jacobs, E.J.; Gapstur, S.M. Social isolation and mortality in US black and white men and women. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 188, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shankar, A.; McMunn, A.; Demakakos, P.; Hamer, M.; Steptoe, A. Social isolation and loneliness: Prospective associations with functional status in older adults. Health Psychol. 2017, 36, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reese, J.B.; Somers, T.J.; Keefe, F.J.; Mosley-Williams, A.; Lumley, M.A. Pain and functioning of rheumatoid arthritis patients based on marital status: Is a distressed marriage preferable to no marriage? J. Pain 2010, 11, 958–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yiengprugsawan, V.S.; Piggott, J.; Witoelar, F.; Blyth, F.M.; Cumming, R.G. Pain and its impact on functional health: 7-Year longitudinal findings among middle-aged and older adults in Indonesia. Geriatrics 2020, 5, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonsick, E.M.; Aronson, B.; Schrack, J.A.; Hicks, G.E.; Jerome, G.J.; Patel, K.V.; Studenski, S.A.; Ferrucci, L. Lumbopelvic pain and threats to walking ability in well-functioning older adults: Findings from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2018, 66, 714–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Byun, M.; Kim, M. Physical and psychological factors associated with poor self-reported health status in older adults with falls. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leveille, S.G.; Jones, R.N.; Kiely, D.K.; Hausdorff, J.M.; Shmerling, R.H.; Guralnik, J.M.; Kiel, D.P.; Lipsitz, L.A.; Bean, J.F. Chronic musculoskeletal pain and the occurrence of falls in an older population. JAMA 2009, 302, 2214–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perruccio, A.V.; Davis, A.M.; Hogg-Johnson, S.; Badley, E.M. Importance of self-rated health and mental well-being in predicting health outcomes following total joint replacement surgery for osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res. Hoboken 2011, 63, 973–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jindai, K.; Nielson, C.M.; Vorderstrasse, B.A.; Quinones, A.R. Multimorbidity and functional limitations among adults 65 or older, NHANES 2005–2012. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2016, 13, 160174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shillo, P.; Sloan, G.; Greig, M.; Hunt, L.; Selvarajah, D.; Elliott, J.; Gandhim, R.; Wilkinson, I.D.; Tesfaye, S. Painful and painless diabetic neuropathies: What is the difference? Curr. Diab Rep. 2019, 19, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke: Diabetic Neuropathy Information Page. Available online: https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/All-Disorders/Diabetic-Neuropathy-Information-Page (accessed on 18 July 2020).

- Fong, J.H. Disability incidence and functional decline among older adults with major chronic diseases. BMC Geriatr. 2019, 19, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Axon, D.R.; Chien, J. Predicotrs of mental health status among older United States adults with pain. Behav. Sci. 2021, 11, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, C.J.L. The state of US health, 1990-2010: Burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. JAMA 2013, 310, 591–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spartano, N.L.; Lyass, A.; Larson, M.G.; Tran, T.; Andersson, C.; Blease, S.J.; Esliger, D.W.; Vasan, R.S.; Murabito, J.M. Objective physical activity and physical performance in middle-aged and older adults. Exp. Gerontol. 2019, 119, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pahor, M.; Guralnik, J.M.; Ambrosius, W.T.; Blair, S.; Bonds, D.E.; Church, T.S.; Espeland, M.A.; Fielding, R.A.; Gill, T.M.; Groessl, E.J.; et al. Effect of structured physical activity on prevention of major mobility disability in older adults: The LIFE study randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014, 311, 2387–2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Axon, D.R.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Warholak, T.L.; Slack, M.K. Xm2 scores for estimating total exposure to multimodal strategies identified by pharmacists for managing pain: Validity testing and clinical relevance. Pain Res. Manag. 2018, 2530286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rogerson, M.D.; Gatchel, R.J.; Bierner, S.M. A cost utility analysis of interdisciplinary early intervention versus treatment as usual for high-risk acute low back pain patients. Pain Pract. 2010, 10, 382–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidel, D.; Brayne, C.; Jagger, C. Limitations in physical functioning among older people as a predictor of subsequent disability in instrumental activities of daily living. Age Ageing 2011, 40, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mehta, S.P.; Morelli, N.; Prevatte, C.; White, D.; Oliashirazi, A. Validation of physical performance tests in individuals with advanced knee osteoarthritis. HSS J. 2019, 15, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, S.M.; Tallian, K.; Nguyen, V.T.; Dyke, J.V.; Sikand, H. Does early physical therapy intervention reduce opioid burden and improve functionality in the management of chronic lower back pain? Ment. Health Clin. 2020, 10, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Total Weighted N = 57,051,651 | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functional Limitation (Weighted N = 22,417,233) Weighted % (95% CI) | No Functional Limitation (Weighted N = 34,634,419) Weighted % (95% CI) | ||||

| Predisposing factors: | |||||

| Gender | <0.0001 | ||||

| Female | 60.4 (57.8–62.9) | 51.9 (50.2–53.7) | |||

| Male | 39.6 (37.1–42.2) | 48.1 (46.3–49.8) | |||

| Age | <0.0001 | ||||

| ≥65 years | 59.8 (57.1–62.6) | 45.3 (42.9–47.7) | |||

| 50–64 years | 40.2 (37.4–42.9) | 54.7 (52.3–57.1) | |||

| Race | 0.5393 | ||||

| White | 80.7 (78.7–82.7) | 81.4 (79.4–83.4) | |||

| Other | 19.3 (17.3–21.3) | 18.6 (16.6–20.6) | |||

| Ethnicity | <0.0001 | ||||

| Non-Hispanic | 92.4 (91.0–93.9) | 88.3 (86.6–90.0) | |||

| Hispanic | 7.6 (6.1–9.0) | 11.7 (10.0–13.4) | |||

| Enabling factors: | |||||

| Education level | <0.0001 | ||||

| <High school | 19.6 (17.4–21.8) | 14.1 (12.6–15.6) | |||

| High school | 33.6 (31.4–35.7) | 32.7 (30.6–34.7) | |||

| >High school | 46.8 (44.1–49.6) | 53.2 (50.8–55.7) | |||

| Employment status | <0.0001 | ||||

| Employed | 20.3 (17.7–22.9) | 51.1 (48.5–53.7) | |||

| Unemployed | 79.7 (77.1–82.3) | 48.9 (46.3–51.5) | |||

| Health insurance coverage | <0.0001 | ||||

| Private | 50.7 (47.9–53.6) | 67.7 (65.6–69.8) | |||

| Public | 47.0 (44.2–49.8) | 27.9 (25.9–29.9) | |||

| Uninsured | 2.3 (1.6–3.0) | 4.4 (3.6–5.2) | |||

| Income | <0.0001 | ||||

| Poor/near poor/low income | 42.5 (39.4–45.7) | 25.5 (23.5–27.5) | |||

| Middle/high income | 57.5 (54.3–60.6) | 74.5 (72.5–76.5) | |||

| Marital status | <0.0001 | ||||

| Married | 46.0 (43.0–49.0) | 64.4 (62.2–66.5) | |||

| Other | 54.0 (51.0–57.0) | 35.6 (33.5–37.8) | |||

| Need factors: | |||||

| Perceived pain intensity | <0.0001 | ||||

| Little/moderate | 56.5 (53.6–59.4) | 87.1 (85.5–88.6) | |||

| Quite a bit/extreme | 43.5 (40.6–46.4) | 12.9 (11.4–14.5) | |||

| Perceived mental health condition | <0.0001 | ||||

| Excellent/very good/good | 77.5 (75.4–79.7) | 90.7 (89.6–91.8) | |||

| Fair/poor | 22.5 (20.3–24.6) | 9.3 (8.3–10.4) | |||

| Perceived physical health condition | <0.0001 | ||||

| Excellent/very good/good | 56.5 (54.0–59.1) | 83.6 (82.1–85.2) | |||

| Fair/poor | 43.5 (40.9–46.0) | 16.4 (14.8–17.9) | |||

| Total number of prevalent chronic health conditions | <0.0001 | ||||

| 0 | 0.8 (0.4–1.3) | 7.5 (6.2–8.8) | |||

| 1 | 3.3 (2.2–4.3) | 14.6 (13.2–16.0) | |||

| 2 | 11.3 (9.4–13.1) | 18.5 (16.7–20.2) | |||

| 3 | 14.7 (13.0–16.5) | 21.6 (19.8–23.3) | |||

| 4 | 17.8 (15.8–19.8) | 15.7 (14.3–17.2) | |||

| ≥5 | 52.1 (49.3–54.9) | 22.2 (20.4–23.9) | |||

| Personal health practices and environmental factors: | |||||

| Frequent physical activity status | <0.0001 | ||||

| Yes | 31.6 (29.0–34.2) | 48.6 (46.2–51.0) | |||

| No | 68.4 (65.8–71.0) | 51.4 (49.0–53.8) | |||

| Current smoking status | 0.0098 | ||||

| Yes | 16.7 (14.9–18.4) | 13.7 (12.2–15.2) | |||

| No | 83.3 (81.6–85.1) | 86.3 (84.8–87.8) | |||

| US census region | 0.0458 | ||||

| Northeast | 17.0 (14.6–19.4) | 18.9 (16.9–21.0) | |||

| Midwest | 22.7 (20.3–25.2) | 21.6 (19.4–23.9) | |||

| South | 40.7 (37.8–43.6) | 36.6 (33.9–39.3) | |||

| West | 19.5 (17.2–21.9) | 22.8 (20.4–25.3) | |||

| Factors | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Predisposing factors: | |||

| Gender | |||

| Female | 1.24 (1.04, 1.47) | ||

| Male | Reference | ||

| Age | |||

| ≥65 years | 1.01 (0.84, 1.22) | ||

| 50–64 years | Reference | ||

| Race | |||

| White | 1.24 (1.03, 1.50) | ||

| Other | Reference | ||

| Ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic | 1.69 (1.31, 2.18) | ||

| Hispanic | Reference | ||

| Enabling factors: | |||

| Education level | |||

| <High school | 0.84 (0.67, 1.05) | ||

| High school | 0.89 (0.75, 1.06) | ||

| >High school | Reference | ||

| Employment status | |||

| Employed | 0.51 (0.41, 0.64) | ||

| Unemployed | Reference | ||

| Health insurance coverage | |||

| Private | 1.23 (0.79, 1.92) | ||

| Public | 1.46 (0.94, 2.26) | ||

| Uninsured | Reference | ||

| Income | |||

| Poor/near poor/low income | 0.99 (0.82, 1.21) | ||

| Middle/high income | Reference | ||

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 0.57 (0.48, 0.67) | ||

| Other | Reference | ||

| Need factors: | |||

| Perceived pain intensity | |||

| Little/moderate | 0.36 (0.29, 0.44) | ||

| Quite a bit/extreme | Reference | ||

| Perceived mental health condition | |||

| Excellent/very good/good | 0.89 (0.70, 1.13) | ||

| Fair/poor | Reference | ||

| Perceived physical health condition | |||

| Excellent/very good/good | 0.48 (0.39, 0.59) | ||

| Fair/poor | Reference | ||

| Total number of prevalent chronic health conditions | |||

| 0 | 0.11 (0.06, 0.20) | ||

| 1 | 0.20 (0.13, 0.30) | ||

| 2 | 0.43 (0.33, 0.56) | ||

| 3 | 0.45 (0.36, 0.56) | ||

| 4 | 0.66 (0.53, 0.84) | ||

| ≥5 | Reference | ||

| Personal health practices and environmental factors: | |||

| Frequent physical activity status | |||

| Yes | 0.74 (0.62, 0.88) | ||

| No | Reference | ||

| Current smoking status | |||

| Yes | 0.95 (0.77, 1.17) | ||

| No | Reference | ||

| US census region | |||

| Midwest | 0.94 (0.70, 1.27) | ||

| Northeast | 1.16 (0.87, 1.54) | ||

| South | 1.07 (0.83, 1.37) | ||

| West | Reference | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Axon, D.R.; Le, D. Association of Self-Reported Functional Limitations among a National Community-Based Sample of Older United States Adults with Pain: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1836. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10091836

Axon DR, Le D. Association of Self-Reported Functional Limitations among a National Community-Based Sample of Older United States Adults with Pain: A Cross-Sectional Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2021; 10(9):1836. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10091836

Chicago/Turabian StyleAxon, David R., and Darlena Le. 2021. "Association of Self-Reported Functional Limitations among a National Community-Based Sample of Older United States Adults with Pain: A Cross-Sectional Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 10, no. 9: 1836. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10091836

APA StyleAxon, D. R., & Le, D. (2021). Association of Self-Reported Functional Limitations among a National Community-Based Sample of Older United States Adults with Pain: A Cross-Sectional Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(9), 1836. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10091836