Mobile Bearing versus Fixed Bearing for Unicompartmental Arthroplasty in Monocompartmental Osteoarthritis of the Knee: A Meta-Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Selection and Data Collection

2.4. Data Items

2.5. Study Risk of Bias Assessment

2.6. Synthesis Methods

3. Results

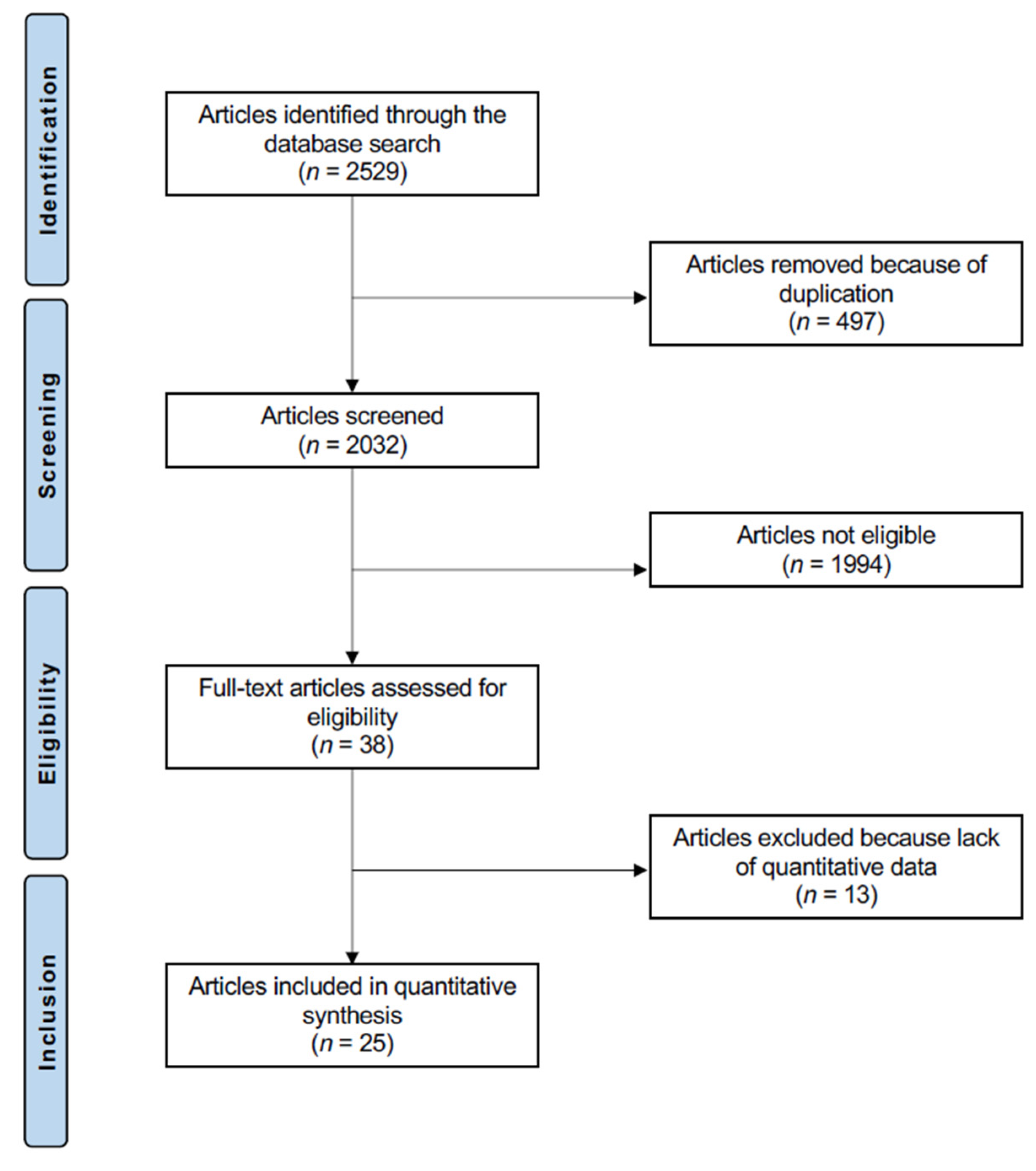

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Methodological Quality Assessment

3.3. Risk of Publication Bias

3.4. Study Characteristics and Results of Individual Studies

3.5. Results of Syntheses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Ethical Approval

References

- Oliveria, S.A.; Felson, D.T.; Reed, J.I.; Cirillo, P.A.; Walker, A.M. Incidence of symptomatic hand, hip and knee osteoarthritis among patients in a health maintenance organisation. Arthritis Rheum. 1995, 38, 1134–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tille, E.; Beyer, F.; Auerbach, K.; Tinius, M.; Lutzner, J. Better short-term function after unicompartmental compared to total knee arthroplasty. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2021, 22, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panzram, B.; Bertlich, I.; Reiner, T.; Walker, T.; Hagmann, S.; Gotterbarm, T. Cementless unicompartmental knee replacement allows early return to normal activity. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2018, 19, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kozinn, S.C.; Scott, R. Unicondylar knee arthroplasty. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 1989, 71, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiss, F.; Gotz, J.S.; Maderbacher, G.; Zeman, F.; Meissner, W.; Grifka, J.; Benditz, A.; Greimel, F. Pain management of unicompartmental (UKA) vs. total knee arthroplasty (TKA) based on a matched pair analysis of 4144 cases. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argenson, J.N. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty versus total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2017, 25, 681–686. [Google Scholar]

- Migliorini, F.; Tingart, M.; Niewiera, M.; Rath, B.; Eschweiler, J. Unicompartmental versus total knee arthroplasty for knee osteoarthritis. Eur. J. Orthop. Surg. Traumatol. 2019, 29, 947–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peersman, G.; Stuyts, B.; Vandenlangenbergh, T.; Cartier, P.; Fennema, P. Fixed-versus mobile-bearing UKA: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2015, 23, 3296–3305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, J.; Li, H.; Wang, W.; George, D.M.; Huang, T. Fixed- versus mobile-bearing unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: A meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 19075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capella, M.; Dolfin, M.; Saccia, F. Mobile bearing and fixed bearing total knee arthroplasty. Ann. Transl. Med. 2016, 4, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schneider, D.T.; Ostermeier, P.S.; Rinio, D.M.; Marquaß, P.D.B. Fixed vs Mobile Bearing Prothesis. Available online: https://www.joint-surgeon.com/orthopedic-services/knee/total-replacement-knee-types-of-procedures (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Huang, F.; Wu, D.; Chang, J.; Zhang, C.; Qin, K.; Liao, F.; Yin, Z. A Comparison of Mobile- and Fixed-Bearing Unicompartmental Knee Arthroplasties in the Treatment of Medial Knee Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of 1861 Patients. J. Knee Surg. 2021, 34, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Confalonieri, N.; Manzotti, A.; Pullen, C. Comparison of a mobile with a fixed tibial bearing unicompartimental knee prosthesis: A prospective randomized trial using a dedicated outcome score. Knee 2004, 11, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, J.P.; Fan, J.C.H.; Lau, L.C.M.; Tse, T.T.S.; Wan, S.Y.C.; Hung, Y.W. Can accuracy of component alignment be improved with Oxford UKA Microplasty(R) instrumentation? J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2020, 15, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koppens, D.; Rytter, S.; Munk, S.; Dalsgaard, J.; Sorensen, O.G.; Hansen, T.B.; Stilling, M. Equal tibial component fixation of a mobile-bearing and fixed-bearing medial unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: A randomized controlled RSA study with 2-year follow-up. Acta Orthop. 2019, 90, 575–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Whittaker, J.P.; Naudie, D.D.; McAuley, J.P.; McCalden, R.W.; MacDonald, S.J.; Bourne, R.B. Does bearing design influence midterm survivorship of unicompartmental arthroplasty? Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2010, 468, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bruce, D.J.; Hassaballa, M.; Robinson, J.R.; Porteous, A.J.; Murray, J.R.; Newman, J.H. Minimum 10-year outcomes of a fixed bearing all-polyethylene unicompartmental knee arthroplasty used to treat medial osteoarthritis. Knee 2020, 27, 1018–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neufeld, M.E.; Albers, A.; Greidanus, N.V.; Garbuz, D.S.; Masri, B.A. A Comparison of Mobile and Fixed-Bearing Unicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty at a Minimum 10-Year Follow-up. J. Arthroplast. 2018, 33, 1713–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, Y.B.; Gujarathi, M.R.; Oh, K.J. Outcome of Unicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty: A Systematic Review of Comparative Studies between Fixed and Mobile Bearings Focusing on Complications. Knee Surg. Relat. Res. 2015, 27, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.; Chen, D.; Zhu, C.; Pan, X.; Mao, X.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, X. Fixed- versus mobile-bearing unicondylar knee arthroplasty: Are failure modes different? Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2013, 21, 2433–2441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, J.A.; Kleeblad, L.J.; Sierevelt, I.N.; Horstmann, W.G.; Nolte, P.A. Bearing design influences short- to mid-term survivorship, but not functional outcomes following lateral unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: A systematic review. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2019, 27, 2276–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deckard, E.R.; Jansen, K.; Ziemba-Davis, M.; Sonn, K.A.; Meneghini, R.M. Does Patellofemoral Disease Affect Outcomes in Contemporary Medial Fixed-Bearing Unicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty? J. Arthroplast. 2020, 35, 2009–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilmour, A.; MacLean, A.; Rowe, P.; Banger, M.; Donnelly, I.; Jones, B.; Blyth, M. Robotic-Arm Assisted Versus Conventional Unicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty. The 2 year Results of a Randomised Controlled Trial. J. Arthroplast. 2018, 33, S109–S115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kayani, B.; Konan, S.; Tahmassebi, J.; Rowan, F.E.; Haddad, F.S. An assessment of early functional rehabilitation and hospital discharge in conventional versus robotic-arm assisted unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: A prospective cohort study. Bone Jt. J. 2019, 101, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazarian, G.S.; Barrack, T.N.; Okafor, L.; Barrack, R.L.; Nunley, R.M.; Lawrie, C.M. High Prevalence of Radiographic Outliers and Revisions with Unicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2020, 102, 1151–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.S.; Koh, I.J.; Kim, C.K.; Choi, K.Y.; Baek, J.W.; In, Y. Comparison of implant position and joint awareness between fixed- and mobile-bearing unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: A minimum of five year follow-up study. Int. Orthop. 2020, 44, 2329–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howick, J.C.I.; Glasziou, P.; Greenhalgh, T.; Carl Heneghan Liberati, A.; Moschetti, I.; Phillips, B.; Thornton, H.; Goddard, O.; Hodgkinson, M. The 2011 Oxford CEBM Levels of Evidence. Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. 2011. Available online: https://www.cebm.net/index.aspx?o=5653 (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insall, J.N.; Dorr, L.D.; Scott, R.D.; Scott, W.N. Rationale of the Knee Society clinical rating system. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1989, 248, 13–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, D.W.; Fitzpatrick, R.; Rogers, K.; Pandit, H.; Beard, D.J.; Carr, A.J.; Dawson, J. The use of the Oxford hip and knee scores. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Br. 2007, 89, 1010–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Artz, N.J.; Hassaballa, M.A.; Robinson, J.R.; Newman, J.H.; Porteous, A.J.; Murray, J.R. Patient Reported Kneeling Ability in Fixed and Mobile Bearing Knee Arthroplasty. J. Arthroplast. 2015, 30, 2159–2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, R.; Scott, C.E.; Morris, H.E.; Wade, F.; Nutton, R.W. Survivorship and patient satisfaction of a fixed bearing unicompartmental knee arthroplasty incorporating an all-polyethylene tibial component. Knee 2012, 19, 348–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biau, D.J.; Greidanus, N.V.; Garbuz, D.S.; Masri, B.A. No difference in quality-of-life outcomes after mobile and fixed-bearing medial unicompartmental knee replacement. J. Arthroplast. 2013, 28, 220–226.e221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catani, F.; Benedetti, M.G.; Bianchi, L.; Marchionni, V.; Giannini, S.; Leardini, A. Muscle activity around the knee and gait performance in unicompartmental knee arthroplasty patients: A comparative study on fixed- and mobile-bearing designs. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2012, 20, 1042–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emerson, R.H., Jr.; Hansborough, T.; Reitman, R.D.; Rosenfeldt, W.; Higgins, L.L. Comparison of a mobile with a fixed-bearing unicompartmental knee implant. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2002, 404, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forster, M.C.; Bauze, A.J.; Keene, G.C. Lateral unicompartmental knee replacement: Fixed or mobile bearing? Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2007, 15, 1107–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleeson, R.E.; Evans, R.; Ackroyd, C.E.; Webb, J.; Newman, J.H. Fixed or mobile bearing unicompartmental knee replacement? A comparative cohort study. Knee 2004, 11, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, A.; Arai, Y.; Nakagawa, S.; Inoue, H.; Yamazoe, S.; Kubo, T. Comparison of Alignment Correction Angles Between Fixed-Bearing and Mobile-Bearing UKA. J. Arthroplast. 2016, 31, 142–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.T.; Lee, S.; Lee, J.I.; Kim, J.W. Analysis and Treatment of Complications after Unicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty. Knee Surg. Relat. Res. 2016, 28, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.G.; Yao, F.; Joss, B.; Ioppolo, J.; Nivbrant, B.; Wood, D. Mobile vs. fixed bearing unicondylar knee arthroplasty: A randomized study on short term clinical outcomes and knee kinematics. Knee 2006, 13, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozcan, C.; Simsek, M.E.; Tahta, M.; Akkaya, M.; Gursoy, S.; Bozkurt, M. Fixed-bearing unicompartmental knee arthroplasty tolerates higher variance in tibial implant rotation than mobile-bearing designs. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2018, 138, 1463–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parratte, S.; Pauly, V.; Aubaniac, J.M.; Argenson, J.N. No long-term difference between fixed and mobile medial unicompartmental arthroplasty. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2012, 470, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pronk, Y.; Paters, A.A.M.; Brinkman, J.M. No difference in patient satisfaction after mobile bearing or fixed bearing medial unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2021, 29, 947–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, S.S.; Kim, C.W.; Lee, C.R.; Kwon, Y.U.; Oh, M.; Kim, O.G.; Kim, C.K. Long-term outcomes of unicompartmental knee arthroplasty in patients requiring high flexion: An average 10-year follow-up study. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2019, 139, 1633–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tecame, A.; Savica, R.; Rosa, M.A.; Adravanti, P. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in association with medial unicompartmental knee replacement: A retrospective study comparing clinical and radiological outcomes of two different implant design. Int. Orthop. 2019, 43, 2731–2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verdini, F.; Zara, C.; Leo, T.; Mengarelli, A.; Cardarelli, S.; Innocenti, B. Assessment of patient functional performance in different knee arthroplasty designs during unconstrained squat. Muscle Ligaments Tendons J. 2017, 7, 514–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.O.; Hing, C.B.; Davies, L.; Donell, S.T. Fixed versus mobile bearing unicompartmental knee replacement: A meta-analysis. Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. 2009, 95, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ammarullah, M.I.; Afif, I.Y.; Maula, M.I.; Winarni, T.I.; Tauviqirrahman, M.; Akbar, I.; Basri, H.; van der Heide, E.; Jamari, J. Tresca Stress Simulation of Metal-on-Metal Total Hip Arthroplasty during Normal Walking Activity. Materials 2021, 14, 7554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamari, J.; Ammarullah, M.I.; Saad, A.P.M.; Syahrom, A.; Uddin, M.; van der Heide, E.; Basri, H. The Effect of Bottom Profile Dimples on the Femoral Head on Wear in Metal-on-Metal Total Hip Arthroplasty. J. Funct. Biomater. 2021, 12, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, J.J.; Goodfellow, J.W. Theory and practice of meniscal knee replacement: Designing against wear. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part H 1996, 210, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kendrick, B.J.; Longino, D.; Pandit, H.; Svard, U.; Gill, H.S.; Dodd, C.A.; Murray, D.W.; Price, A.J. Polyethylene wear in Oxford unicompartmental knee replacement: A retrieval study of 47 bearings. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Br. 2010, 92, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brockett, C.L.; Jennings, L.M.; Fisher, J. The wear of fixed and mobile bearing unicompartmental knee replacements. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part H 2011, 225, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Argenson, J.N.; Parratte, S. The unicompartmental knee: Design and technical considerations in minimizing wear. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2006, 452, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manson, T.T.; Kelly, N.H.; Lipman, J.D.; Wright, T.M.; Westrich, G.H. Unicondylar knee retrieval analysis. J. Arthroplast. 2010, 25, 108–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zambianchi, F.; Digennaro, V.; Giorgini, A.; Grandi, G.; Fiacchi, F.; Mugnai, R.; Catani, F. Surgeon’s experience influences UKA survivorship: A comparative study between all-poly and metal back designs. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2015, 23, 2074–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridgeway, S.R.; McAuley, J.P.; Ammeen, D.J.; Engh, G.A. The effect of alignment of the knee on the outcome of unicompartmental knee replacement. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Br. 2002, 84, 351–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertsson, O.; Knutson, K.; Lewold, S.; Lidgren, L. The routine of surgical management reduces failure after unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Br. 2001, 83, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author, Year | Journal | Design | Follow-Up (Months) | Bearing | Procedures (n) | Mean Age | Women (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Artz et al., 2015 [31] | J. Arthroplasty | Randomised | 24 | MB | 205 | 62.0 | 50% |

| FB | 284 | 71.4 | 44% | ||||

| Bhattacharya et al., 2012 [32] | Knee | Retrospective | 44.7 | FB | 91 | 67.7 | 58% |

| MB | 49 | 68.8 | 47% | ||||

| Biau et al., 2013 [33] | J. Arthroplasty | Retrospective | 24 | MB | 33 | 67.7 | 59% |

| FB | 57 | 68.8 | 51% | ||||

| Catani et al., 2011 [34] | Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc | Retrospective | 12 | MB | 10 | 70.3 | 80% |

| FB | 10 | 70.3 | 60% | ||||

| Confalonieri et al., 2004 [13] | Knee | Randomised | 68.4 | MB | 20 | 71.0 | 45% |

| FB | 20 | 69.5 | 60% | ||||

| Emerson et al., 2002 [35] | Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. | Prospective | 81.6 | MB | 50 | 63.0 | 56% |

| FB | 51 | 63.0 | 66% | ||||

| Forster et al., 2007 [36] | Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. | Prospective | 24 | FB | 17 | 75.0 | 69% |

| MB | 13 | 55.0 | 42% | ||||

| Gilmour et al., 2018 [23] | J. Arthroplasty | Prospective | 24 | FB | 58 | 61.8 | 45% |

| MB | 54 | 62.6 | 45% | ||||

| Gleeson et al., 2004 [37] | Knee | Randomised | 24 | FB | 57 | 66.7 | 41% |

| MB | 47 | 64.7 | 60% | ||||

| Inoue et al., 2016 [38] | J. Arthroplasty | Retrospective | 27.3 | FB | 24 | 75.0 | 76% |

| MB | 28 | 73.3 | 76% | ||||

| Kayani et al., 2019 [24] | Bone Joint J. | Prospective | 3 | MB | 73 | 66.1 | 53% |

| FB | 73 | 65.3 | 56% | ||||

| Kazarian et al., 2020 [25] | J. Bone Joint Surg. | Retrospective | 44.4 | FB | 162 | 63.2 | 59% |

| MB | 91 | 62.2 | 52% | ||||

| Kim et al., 2016 [39] | Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. | Retrospective | 94 | MB | 1441 | 62.0 62.0 | 91% 91% |

| FB | 135 | ||||||

| Kim et al., 2020 [26] | Int. Orthop. | Retrospective | 60 | FB | 58 | 61.3 | 93% |

| MB | 57 | 60.7 | 84% | ||||

| Koppens et al., 2019 [15] | Acta Orthop. | Randomised | 24 | MB | 33 | 64.0 | 52% |

| FB | 32 | 61.0 | 47% | ||||

| Li et al., 2006 [40] | Knee | Randomised | 24 | FB | 28 | 70.0 | 32% |

| MB | 28 | 74.0 | 29% | ||||

| Neufeld et al., 2018 [18] | J Arthroplasty | Retrospective | 120 | MB | 38 | 60.3 | 58% |

| FB | 68 | 64.6 | 50% | ||||

| Ozcan et al., 2018 [41] | Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. | Retrospective | 28.8 | FB | 153 | ||

| MB | 171 | ||||||

| Paratte et al., 2011 [42] | Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. | Retrospective | 180 | FB | 79 | 62.8 | 63% |

| MB | 77 | 63.4 | 68% | ||||

| Patrick et al., 2020 [14] | J. Orthop. Surg. Res. | Retrospective | 14.4 | MB | 150 | 68.6 | 53% |

| FB | 44 | 67.7 | 86% | ||||

| Pronk et al., 2020 [43] | Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. | Retrospective | 12 | MB | 66 | 61.4 | 47% |

| FB | 97 | 61.2 | 44% | ||||

| Seo et al., 2019 [44] | Arch. Ortho.p Trauma Surg. | Retrospective | 120 | MB | 36 | 64.5 | 97% |

| FB | 60 | 61.8 | 95% | ||||

| Tecame et al., 2018 [45] | Int. Orthop. | Retrospective | 42 | MB | 9 | 47.8 | 17% |

| FB | 15 | 48.4 | |||||

| Verdini et al., 2017 [46] | Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. | Prospective | 20 | MB | 7 | 68.0 | 60% |

| FB | 8 | 67.0 | 40% | ||||

| Whittaker et al., 2010 [16] | Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. | Retrospective | 3.6 | FB | 150 | 68.0 | 53% |

| MB | 79 | 63.0 | 48% |

| Endpoint | MB | FB | Model | 95% CI | Final Effect | p | I2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROM | 243 | 249 | Fixed | −4.37, −0.04 | −2.21 | 0.05 | 0 |

| KSS | 487 | 548 | Random | −6.38, 5.64 | −0.37 | 0.9 | 99 |

| KSFS | 176 | 241 | Fixed | −1.92, 0.31 | −0.81 | 0.2 | 0 |

| OKS | 97 | 95 | Random | −11.56, 4.44 | −3.56 | 0.4 | 95 |

| Revision | 2353 | 1148 | Random | 0.82, 3.20 | 1.62 | 0.2 | 52 |

| Aseptic Loosening | 1810 | 658 | Random | 0.16, 7.96 | 1.12 | 0.9 | 89 |

| Deep Infections | 1781 | 404 | Fixed | 0.28, 3.47 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0 |

| Fractures | 1679 | 277 | Random | 0.08, 4.85 | 0.61 | 0.6 | 62 |

| OA Progression | 1752 | 602 | Fixed | 0.81, 2.60 | 1.45 | 0.2 | 3 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Migliorini, F.; Maffulli, N.; Cuozzo, F.; Elsner, K.; Hildebrand, F.; Eschweiler, J.; Driessen, A. Mobile Bearing versus Fixed Bearing for Unicompartmental Arthroplasty in Monocompartmental Osteoarthritis of the Knee: A Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 2837. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11102837

Migliorini F, Maffulli N, Cuozzo F, Elsner K, Hildebrand F, Eschweiler J, Driessen A. Mobile Bearing versus Fixed Bearing for Unicompartmental Arthroplasty in Monocompartmental Osteoarthritis of the Knee: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2022; 11(10):2837. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11102837

Chicago/Turabian StyleMigliorini, Filippo, Nicola Maffulli, Francesco Cuozzo, Karen Elsner, Frank Hildebrand, Jörg Eschweiler, and Arne Driessen. 2022. "Mobile Bearing versus Fixed Bearing for Unicompartmental Arthroplasty in Monocompartmental Osteoarthritis of the Knee: A Meta-Analysis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 11, no. 10: 2837. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11102837

APA StyleMigliorini, F., Maffulli, N., Cuozzo, F., Elsner, K., Hildebrand, F., Eschweiler, J., & Driessen, A. (2022). Mobile Bearing versus Fixed Bearing for Unicompartmental Arthroplasty in Monocompartmental Osteoarthritis of the Knee: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 11(10), 2837. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11102837