Traumatology: Adoption of the Sm@rtEven Application for the Remote Evaluation of Patients and Possible Medico-Legal Implications

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- −

- Has undergone reduction and synthesis surgery;

- −

- 18–75 age range;

- −

- Absence of degenerative and oncological cognitive conditions;

- −

- Absence of language barriers;

- −

- Has a smartphone with an Android operating system.

- −

- Progression of the load on the affected limb measured in kg (weight);

- −

- Number of steps taken by the patient during the day;

- −

- Body temperature;

- −

- Administration of a daily evaluation questionnaire.

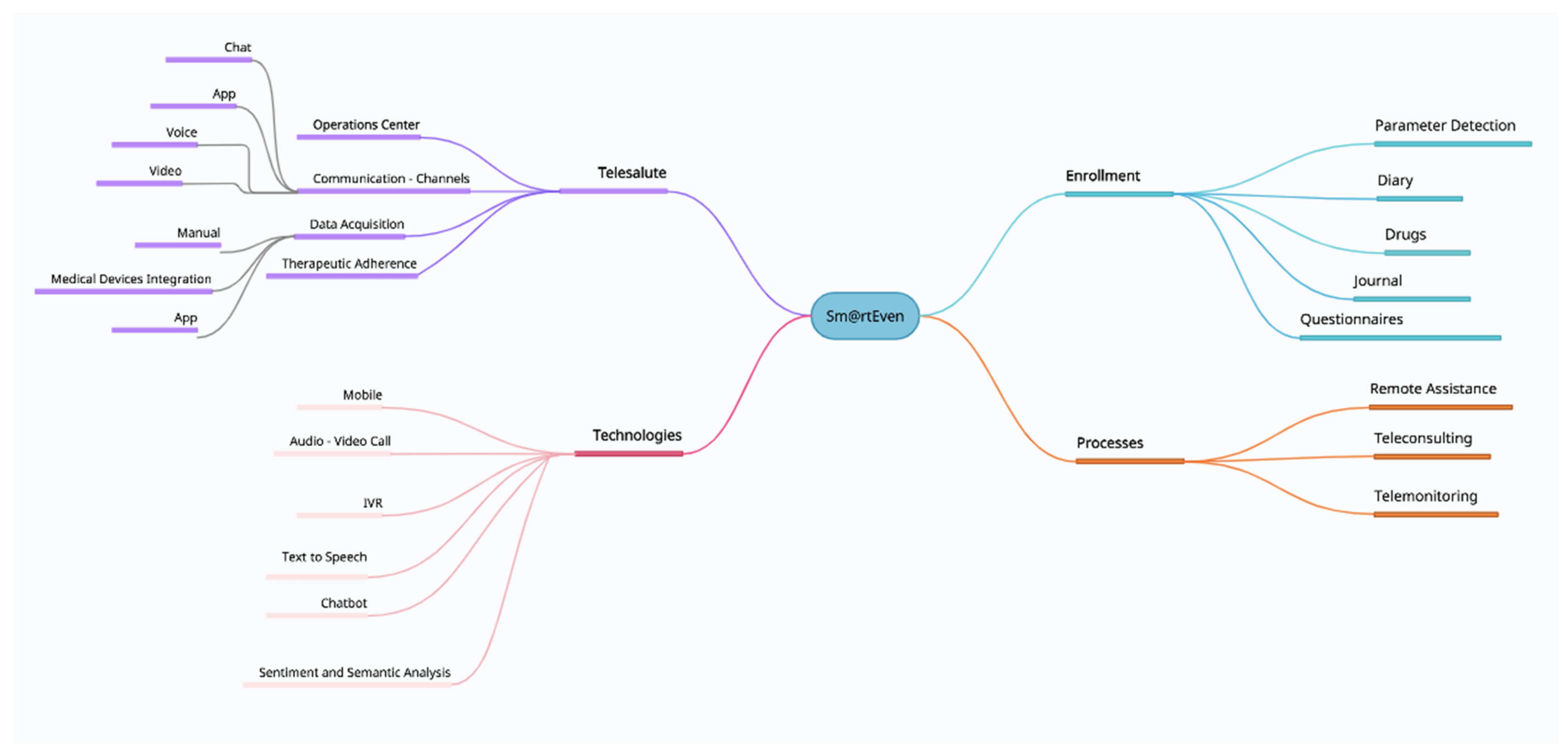

2.1. Sm@rtEven Application System

- Diary: List of the activities that the patient must carry out on the current date (parameter detection, drug administration, etc.) and the activities still to be performed from the previous day.

- Drugs: List of drugs prescribed and drugs not taken in the previous days. In the diary, it is possible to note the assumption, postponement, or refusal of the prescribed drug therapy.

- Parameter detection: List of vital signs to be detected and the measurements left unfinished from the previous day. After synchronization between the application and the wireless device, the data transmission occurs automatically after confirmation by the patient. For the body temperature parameter, the patient must manually enter the value in the dedicated section through guided steps.

- Activities to be carried out: List of activities to be carried out (specialist visits, etc.) and activities that remained unfinished from the previous day.

- Journal: Allows the patient to enter a note and attach audio files, documents, or images. The application also allows the patient to record a short voice message or attach a file from the smartphone’s memory. Instant photos can be taken as well (Figure 3D–F).

- Questionnaires: In this section, the patient can fill in the scheduled daily questionnaires. The notification to remind the patient to fill in the questionnaire appears in the diary. There are three different types of answers: binary, multiple-choice, and open answers.

2.2. First Protocol

- Is the foot of the operated limb swollen?

- Do you feel tingling in the operated limb?

- Is the dressing in order?

- Are there any secretions from the wound?

- How many crutches are you using?

- How are you feeling today?

- Are you able to be autonomous in daily activities?

- Do you have a fever?

- Did you experience headaches or dizziness?

- Describe all side effects.

2.3. Second Protocol

- Is the foot of the operated limb swollen?

- Do you feel tingling in the operated limb?

- How many crutches are you using?

- How are you feeling today?

- Are you able to be autonomous in daily activities?

- Do you have a fever?

- Describe any side effects.

3. Results

- −

- From the 1st to the 7th day: 100% of the required parameters and the appropriate filling-in of the questionnaire were recorded;

- −

- From the 8th to the 14th day: registration of the number of steps was equal to 100% of the requested assessments, the temperature parameter to 60%, registration of the load granted on the operated limb to 60%, and completion of the questionnaire to 90%;

- −

- From the 15th to the 21st day: registration of the number of steps was equal to 70% of the requested assessments, registration of the temperature parameter to 40%, registration of the load granted on the operated limb to 40%, and filling in the questionnaire to 60%;

- −

- From the 22nd to the 30th day: the recording of the number of steps was equal to 30% of the requested assessments, recording of the temperature parameter to 10%, recording of the load granted on the operated limb to 10%, and filling in the questionnaire to 30%.

- −

- From the 1st to the 7th day: 100% of the required parameters and the appropriate filling-in of the questionnaire were recorded;

- −

- From the 8th to the 14th day: registration of the number of steps was equal to 100% of the assessments requested, registration of the temperature parameter to 100%, registration of the load granted on the operated limb to 90%, and completion of the questionnaire to 95%.

4. Discussion

“... Computer-based digital technology... The doctor, in the use of IT tools, guarantees the acquisition of consent, the protection of confidentiality, the relevance of the data collected, and, to the extent of his competence, the safety of techniques. The doctor, in the use of information and communication technologies of clinical data, pursues clinical appropriateness and adopts his own decisions in compliance with any multidisciplinary contributions, ensuring the conscious participation of the assisted person. The use of information and communication technologies for the purposes of prevention, diagnosis, treatment, or clinical surveillance, or such as to affect human performance, adheres to the criteria of proportionality, appropriateness, efficacy, and safety, in compliance with the rights of the person and of the application addresses attached...”[18].

“… acting in telemedicine means assuming full professional responsibility, even for the smallest action carried out at a distance. Specifically, the correct management of limitations due to physical distance is part of the aforementioned responsibility in order to guarantee the safety and effectiveness of medical and assistance procedures, as well as compliance with the rules on data processing... In this context, also for the purposes of the management of clinical risk and health responsibility, the correct professional attitude consists in choosing the operational solutions that offer the best guarantees of proportionality, appropriateness, efficacy, safety, and respect of the rights of the person. In summary, it is not a question of choosing the technologies, but the doctor must choose the combination of them that appears the most appropriate from the medical-assistance point of view in the individual case... the execution of telemedicine... is unsafe when using digital tools in the patient’s home to carry out the video call. We remind you that it is clear that all the legislative and ethical rules of the health professions apply exactly to telemedicine health activities... even in not perfect practical conditions, it seems acceptable that the video call can be used by the doctor to support the clinical control of those patients he already knows from having previously visited them at least once…”[23].

- −

- Production defects of the equipment;

- −

- Errors in the installation or implementation of the various components of IT support;

- −

- Omitted/defective/ineffective maintenance;

- −

- Errors in the use of the equipment;

- −

- Errors in data transmission.

4.1. European Norms Reflect Telemedicine Complexities

4.2. Considerable Advantages with a Few Caveats

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chaet, D.; on behalf of the Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs American Medical Association; Clearfield, R.; Sabin, J.E.; Skimming, K. Ethical practice in Telehealth and Telemedicine. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2017, 32, 1136–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Miller, T.E.; Derse, A.R. Between Strangers: The Practice of Medicine Online. Health Aff. 2002, 21, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Paiva, J.O.V.; Andrade, R.M.C.; De Oliveira, P.A.M.; Duarte, P.; Santos, I.S.; Evangelista, A.L.D.P.; Theophilo, R.L.; De Andrade, L.O.M.; Barreto, I.C.D.H.C. Mobile applications for elderly healthcare: A systematic mapping. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brouard, B.; Bardo, P.; Bonnet, C.; Mounier, N.; Vignot, M.; Vignot, S. Mobile Applications in Oncology: Is It Possible for Patients and Healthcare Professionals to Easily Identify Relevant Tools? Ann. Med. 2016, 48, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger-Groch, J.; Keitsch, M.; Reiter, A.; Weiss, S.; Frosch, K.H.; Priemel, M. The Use of Mobile Applications for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Tumors in Orthopaedic Oncology—A Systematic Review. J. Med. Syst. 2021, 45, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Mariblanca, M.; Cano de la Cuerda, R. Mobile Applications in Children with Cerebral Palsy. Neurologia 2021, 36, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omboni, S.; Caserini, M.; Coronetti, C. Telemedicine and M-Health in Hypertension Management: Technologies, Applications and Clinical Evidence. High Blood Press. Cardiovasc. Prev. 2016, 23, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morera, E.P.; De la Torre Díez, I.; Garcia-Zapirain, B.; López-Coronado, M.; Arambarri, J. Security Recommendations for MHealth Apps: Elaboration of a Developer’s Guide. J. Med. Syst. 2016, 40, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljedaani, B.; Babar, M.A. Challenges with Developing Secure Mobile Health Applications: Systematic Review. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2021, 9, e15654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghan, N.; Mitchell, S.M.; Schemitsch, E.H. Rehabilitation after Plate Fixation of Upper and Lower Extremity Fractures. Injury 2018, 49 (Suppl. S1), S72–S77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, L.S.; Schulz, R.M. Patient Compliance—An Overview. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 1992, 17, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, J.; Coster, G. Issues in Patient Compliance. Drugs 1997, 54, 797–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISTAT (Italian National Instute of Statistics) Resident Population of the Milan Metropolitan Area. Issued on 26 September 2017. Last Updated on 17 February 2022. Available online: https://www.cittametropolitana.mi.it/statistica/osservatorio_metropolitano/statistiche_demografiche/popolazione_residente.html (accessed on 18 April 2022).

- World Health Organization. Western Pacific Region Implementing Telemedicine Services during COVID-19: Guiding Principles and Considerations for a Stepwise Approach. Interim Guidance Republished without Changes on 7 May 2021. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/336862/WPR-DSE-2020-032-eng.pdf?sequence=5&isAllowed=y (accessed on 18 April 2022).

- Hall, J.L.; McGraw, D. For Telehealth to Succeed, Privacy and Security Risks Must Be Identified and Addressed. Health Aff. 2014, 33, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huesch, M.D. Privacy Threats When Seeking Online Health Information. JAMA Intern. Med. 2013, 173, 1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Montanari Vergallo, G.; Busardò, F.P.; Zaami, S.; Marinelli, E. The Static Evolution of the New Italian Code of Medical Ethics. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2016, 20, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- National Federation of Doctor Surgeon and Dentists Orders. Code of Medical Ethics. Italy 2016. Available online: https://portale.fnomceo.it/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/CODICE-DEONTOLOGIA-MEDICA-2014-e-aggiornamenti.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2022).

- Brizola, E.; Adami, G.; Baroncelli, G.I.; Bedeschi, M.F.; Berardi, P.; Boero, S.; Brandi, M.L.; Casareto, L.; Castagnola, E.; Fraschini, P.; et al. Providing High-Quality Care Remotely to Patients with Rare Bone Diseases during COVID-19 Pandemic. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2020, 15, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eccleston, C.; Blyth, F.M.; Dear, B.F.; Fisher, E.A.; Keefe, F.J.; Lynch, M.E.; Palermo, T.M.; Reid, M.C.; De Williams, A.C.C. Managing Patients with Chronic Pain during the COVID-19 Outbreak: Considerations for the Rapid Introduction of Remotely Supported (EHealth) Pain Management Services. Pain 2020, 161, 889–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law No. 219, “Norme in Materia di Consenso Informato e di Disposizioni Anticipate di Trattamento” [Norms Governing Informed Consent and Advance Health Directives] Passed on 22 December 2017. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2018/1/16/18G00006/sg (accessed on 18 April 2022).

- Clark, P.A.; Capuzzi, K.; Harrison, J. Telemedicine: Medical, Legal and Ethical Perspectives. Med. Sci. Monit. 2010, 16, RA261–RA272. [Google Scholar]

- Higher Institute of Health. ISS COVID-19 Report No. 12/2020. Interim Indications for Telemedicine Assistance Services during the COVID-19 Health Emergency. Issued on 13 April 2020. Available online: https://www.iss.it/documents/20126/0/Rapporto+ISS+COVID-19+n.+12+EN.pdf/14756ac0-5160-a3d8-b832-8551646ac8c7?t=1591951830300 (accessed on 18 April 2022).

- Greenhalgh, T.; Wherton, J.; Shaw, S.; Morrison, C. Video Consultations for COVID-19. BMJ 2020, 368, m998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hammersley, V.; Donaghy, E.; Parker, R.; McNeilly, H.; Atherton, H.; Bikker, A.; Campbell, J.; McKinstry, B. Comparing the Content and Quality of Video, Telephone, and Face-to-Face Consultations: A Non-Randomised, Quasi-Experimental, Exploratory Study in UK Primary Care. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2019, 69, e595–e604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Montanari Vergallo, G.; Zaami, S. Guidelines and Best Practices: Remarks on the Gelli-Bianco Law. Clin. Ter. 2018, 169, e82–e85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raposo, V.L. Telemedicine: The Legal Framework (or the Lack of It) in Europe. GMS Health Technol. Assess 2016, 12, doc03. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nittari, G.; Khuman, R.; Baldoni, S.; Pallotta, G.; Battineni, G.; Sirignano, A.; Amenta, F.; Ricci, G. Telemedicine Practice: Review of the Current Ethical and Legal Challenges. Telemed. J. e-Health 2020, 26, 1427–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Directive 98/34/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 June 1998 Laying down a Procedure for the Provision of Information in the Field of Technical Standards and Regulations. Document 31998L0034. Official Journal of the European Union L 204, Issued on 21 July 1998. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/1998/34/oj (accessed on 18 April 2022).

- Directive (EU) 2015/1535 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 9 September 2015 Laying down a Procedure for the Provision of Information in the Field of Technical Regulations and of Rules on Information Society Services. Document 32015L1535. Official Journal of the European Union L 241/1. Issued on 9 September 2015. Available online: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2015/1535/oj (accessed on 18 April 2022).

- Callens, S. Telemedicine and European Law. Med. Law 2003, 22, 733–741. [Google Scholar]

- Directive 2000/31/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 8 June 2000 on Certain Legal Aspects of Information Society Services, in Particular Electronic Commerce, in the Internal Market (‘Directive on Electronic Commerce’). Document 32000L0031. Official Journal of the European Union L 178. Issued on 8 June 2000. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2000/31/oj (accessed on 18 April 2022).

- Directive 2002/58/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 12 July 2002 Concerning the Processing of Personal Data and the Protection of Privacy in the Electronic Communications Sector (Directive on Privacy and Electronic Communications). Document 32002L0058. Official Journal of the European Union L 201. Issued on 12 July 2002. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2002/58/oj (accessed on 18 April 2022).

- Solimini, R.; Busardò, F.P.; Gibelli, F.; Sirignano, A.; Ricci, G. Ethical and Legal Challenges of Telemedicine in the Era of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Medicina 2021, 57, 1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission Staff Working Document on the Applicability of the Existing EU Legal Framework to Telemedicine Services. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=SWD:2012:0414:FIN:EN:PDF (accessed on 18 April 2022).

- Widespread Deployment of Telemedicine Services in Europe. Report of the EU eHealth Stakeholder Group on the Widespread deployment of telemedicine services in Europe. Issued on 12 March 2014. Available online: https://slidelegend.com/widespread-deployment-of-telemedicine-services-in-europe_5ae6b4f27f8b9a55078b456d.html (accessed on 18 April 2022).

- European Parliament. Parliamentary Questions. Question for Written Answer E-002140/2020 to the Commission. Issued on 7 April 2020. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/E-9-2020-002140_EN.html (accessed on 18 April 2022).

- Pradhan, R.; Peeters, W.; Boutong, S.; Mitchell, C.; Patel, R.; Faroug, R.; Roussot, M. Virtual Phone Clinics in Orthopaedics: Evaluation of Clinical Application and Sustainability. BMJ Open Qual. 2021, 10, e001349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, A.; Almeida, J.P.; Pinto, S.; Pereira, J.; Oliveira, A.G.; De Carvalho, M. Home Telemonitoring of Non-Invasive Ventilation Decreases Healthcare Utilisation in a Prospective Controlled Trial of Patients with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2010, 81, 1238–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, A.; Horspool, K.A.; Edwards, L.; Thomas, C.L.; Salisbury, C.; Montgomery, A.A.; O’Cathain, A. Who Does Not Participate in Telehealth Trials and Why? A Cross-Sectional Survey. Trials 2015, 16, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Giordano, A.; Scalvini, S.; Zanelli, E.; Corrà, U.; Longobardi, G.L.; Ricci, V.A.; Baiardi, P.; Glisenti, F. Multicenter Randomised Trial on Home-Based Telemanagement to Prevent Hospital Readmission of Patients with Chronic Heart Failure. Int. J. Cardiol. 2009, 131, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montanari Vergallo, G.; Zaami, S.; Marinelli, E. The COVID-19 Pandemic and Contact Tracing Technologies, between Upholding the Right to Health and Personal Data Protection. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2021, 25, 2449–2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paskins, Z.; Crawford-Manning, F.; Bullock, L.; Jinks, C. Identifying and Managing Osteoporosis before and after COVID-19: Rise of the Remote Consultation? Osteoporos. Int. 2020, 31, 1629–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadimo, K.; Kebaetse, M.B.; Ketshogileng, D.; Seru, L.E.; Sebina, K.B.; Kovarik, C.; Balotlegi, K. Bring-Your-Own-Device in Medical Schools and Healthcare Facilities: A Review of the Literature. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2018, 119, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wani, T.A.; Mendoza, A.; Gray, K. Hospital Bring-Your-Own-Device Security Challenges and Solutions: Systematic Review of Gray Literature. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2020, 8, e18175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pugliese, L.; Woodriff, M.; Crowley, O.; Lam, V.; Sohn, J.; Bradley, S. Feasibility of the “Bring Your Own Device” Model in Clinical Research: Results from a Randomized Controlled Pilot Study of a Mobile Patient Engagement Tool. Cureus 2016, 8, e535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ekeland, A.G.; Bowes, A.; Flottorp, S. Effectiveness of Telemedicine: A Systematic Review of Reviews. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2010, 79, 736–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Galea, M.D. Telemedicine in Rehabilitation. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 30, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, C.; Closa, C.; Lucas, E. Telemedicine in rehabilitation: Post-COVID need and opportunity. Rehabilitacion 2020, 54, 225–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eze, N.D.; Mateus, C.; Cravo Oliveira Hashiguchi, T. Telemedicine in the OECD: An Umbrella Review of Clinical and Cost-Effectiveness, Patient Experience and Implementation. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen-Kosterink, S.; Dekker-Van Weering, M.; Van Velsen, L. Patient Acceptance of a Telemedicine Service for Rehabilitation Care: A Focus Group Study. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2019, 125, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number of Steps/Day | Allowed Load (kg) | Body Temperature (°C) | Questionnaire | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Weekly | 7 | 7 | 14 | 7 | 35 |

| Monthly | 30 | 30 | 60 | 30 | 150 |

| Number of Steps/Day | Allowed Load (kg) | Body Temperature (°C) | Questionnaire | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st week | 7 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 18 |

| 2nd week | 14 | 4 | 4 | 14 | 36 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Basile, G.; Accetta, R.; Marinelli, S.; D’Ambrosi, R.; Petrucci, Q.A.; Giorgetti, A.; Nuara, A.; Zaami, S.; Fozzato, S. Traumatology: Adoption of the Sm@rtEven Application for the Remote Evaluation of Patients and Possible Medico-Legal Implications. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3644. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11133644

Basile G, Accetta R, Marinelli S, D’Ambrosi R, Petrucci QA, Giorgetti A, Nuara A, Zaami S, Fozzato S. Traumatology: Adoption of the Sm@rtEven Application for the Remote Evaluation of Patients and Possible Medico-Legal Implications. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2022; 11(13):3644. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11133644

Chicago/Turabian StyleBasile, Giuseppe, Riccardo Accetta, Susanna Marinelli, Riccardo D’Ambrosi, Quirino Alessandro Petrucci, Arianna Giorgetti, Alessandro Nuara, Simona Zaami, and Stefania Fozzato. 2022. "Traumatology: Adoption of the Sm@rtEven Application for the Remote Evaluation of Patients and Possible Medico-Legal Implications" Journal of Clinical Medicine 11, no. 13: 3644. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11133644

APA StyleBasile, G., Accetta, R., Marinelli, S., D’Ambrosi, R., Petrucci, Q. A., Giorgetti, A., Nuara, A., Zaami, S., & Fozzato, S. (2022). Traumatology: Adoption of the Sm@rtEven Application for the Remote Evaluation of Patients and Possible Medico-Legal Implications. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 11(13), 3644. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11133644