Effectiveness of Home-Based Cardiac Rehabilitation, Using Wearable Sensors, as a Multicomponent, Cutting-Edge Intervention: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Search Strategy

2.4. Study Selection Process

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Effect Size Measurement

2.7. Data Synthesis

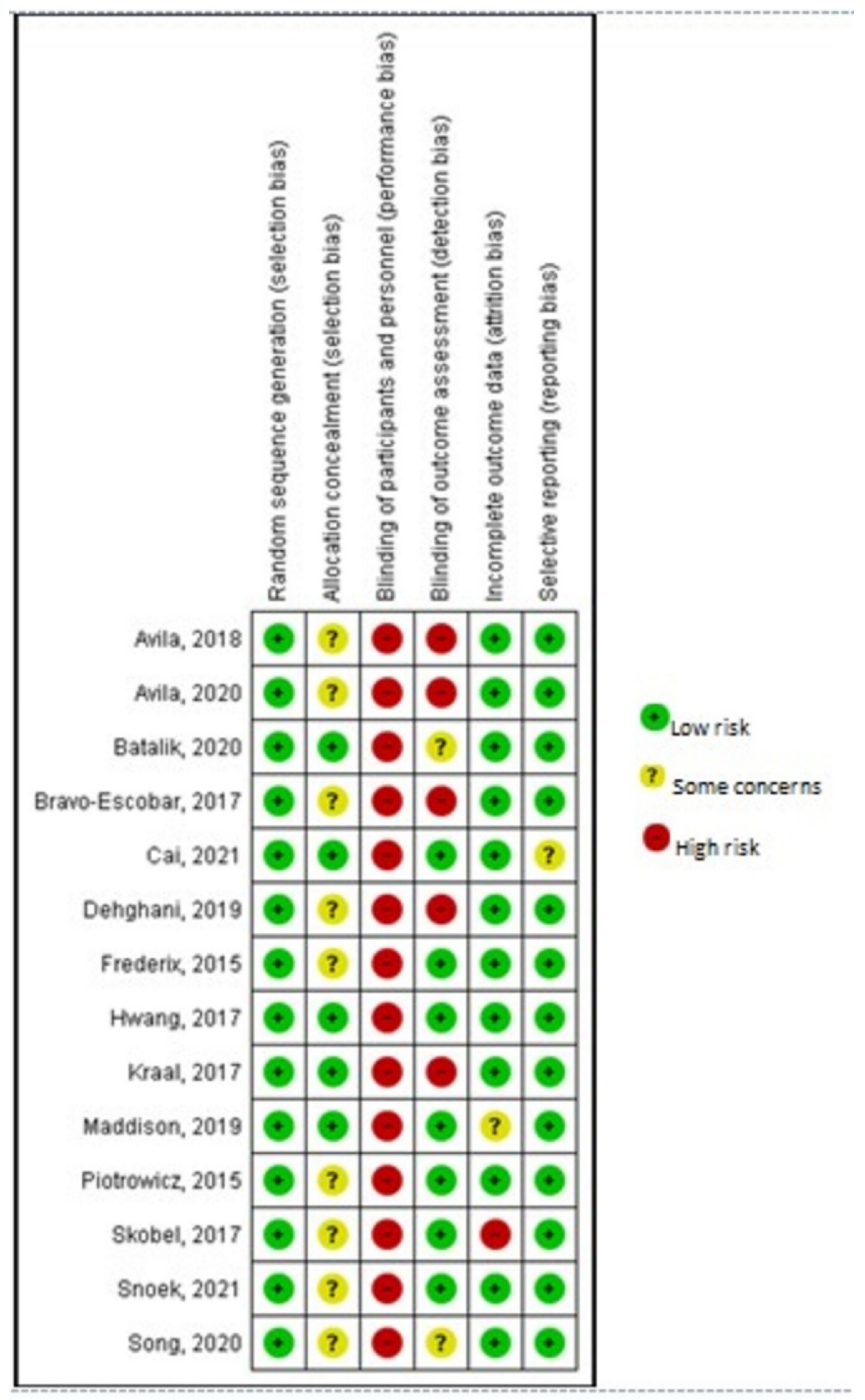

2.8. Risk of Bias (Quality) Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Risk of Bias of Included Studies

3.3. Study Characteristics

3.4. Intervention Characteristics

3.5. Wearable Sensors

4. Primary Outcome

Cardiorespiratory Fitness

5. Secondary Outcomes

5.1. Physical Activity

5.2. Quality of Life

5.3. Training Adherence

5.4. Cardiovascular Risk Factors/Laboratory Parameters

5.5. Stress/Patient Satisfaction

5.6. Muscle Strength/Balance

6. Meta-Analysis

6.1. Cardiorespiratory Fitness

6.2. HBCR versus CBCR

6.3. HBCR versus Usual Care

7. Other Measurements

7.1. Physical Activity

7.2. Quality of Life

7.3. Cardiovascular Risk Factors/Laboratory Parameters

8. Discussion

9. Limitations

10. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Benjamin, E.J.; Muntner, P.; Alonso, A.; Bittencourt, M.S.; Callaway, C.W.; Carson, A.P.; Chamberlain, A.M.; Chang, A.R.; Cheng, S.; Das, S.R.; et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2019 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2019, 139, e56–e528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visseren, F.L.J.; Mach, F.; Smulders, Y.M.; Carballo, D.; Koskinas, K.C.; Bäck, M.; Benetos, A.; Biffi, A.; Boavida, J.-M.; Capodanno, D.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: Developed by the Task Force for cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice with representatives of the European Society of Cardiology and 12 medical societies With the special contribution of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology (EAPC). Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3227–3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shields, G.E.; Wells, A.; Doherty, P.; Heagerty, A.; Buck, D.; Davies, L.M. Cost-effectiveness of cardiac rehabilitation: A systematic review. Heart 2018, 104, 1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piepoli, M.F. Cardiac rehabilitation: What are the latest advances? Dialogues Cardiovasc. Med. 2017, 23, 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Dibben, G.; Faulkner, J.; Oldridge, N.; Rees, K.; Thompson, D.R.; Zwisler, A.D.; Taylor, R.S. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 11, CD001800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, G.; Powell, R.; Kimani, P.; Underwood, M. Does contemporary exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation improve quality of life for people with coronary artery disease? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e036089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, L.; Oldridge, N.; Thompson, D.R.; Zwisler, A.D.; Rees, K.; Martin, N.; Taylor, R.S. Exercise-Based Cardiac Rehabilitation for Coronary Heart Disease: Cochrane Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016, 67, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sandercock, G.R.; Cardoso, F.; Almodhy, M.; Pepera, G. Cardiorespiratory fitness changes in patients receiving comprehensive outpatient cardiac rehabilitation in the UK: A multicentre study. Heart 2013, 99, 785–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prescott, E.; Eser, P.; Mikkelsen, N.; Holdgaard, A.; Marcin, T.; Wilhelm, M.; Gil, C.P.; González-Juanatey, J.R.; Moatemri, F.; Iliou, M.C.; et al. Cardiac rehabilitation of elderly patients in eight rehabilitation units in western Europe: Outcome data from the EU-CaRE multi-centre observational study. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2020, 27, 1716–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotseva, K.; De Backer, G.; De Bacquer, D.; Rydén, L.; Hoes, A.; Grobbee, D.; Maggioni, A.; Marques-Vidal, P.; Jennings, C.; Abreu, A.; et al. Lifestyle and impact on cardiovascular risk factor control in coronary patients across 27 countries: Results from the European Society of Cardiology ESC-EORP EUROASPIRE V registry. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2019, 26, 824–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resurrección, D.M.; Moreno-Peral, P.; Gómez-Herranz, M.; Rubio-Valera, M.; Pastor, L.; Caldas de Almeida, J.M.; Motrico, E. Factors associated with non-participation in and dropout from cardiac rehabilitation programmes: A systematic review of prospective cohort studies. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2019, 18, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santiago de Araújo Pio, C.; Chaves, G.S.; Davies, P.; Taylor, R.S.; Grace, S.L. Interventions to promote patient utilisation of cardiac rehabilitation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 2, Cd007131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ruano-Ravina, A.; Pena-Gil, C.; Abu-Assi, E.; Raposeiras, S.; van ‘t Hof, A.; Meindersma, E.; Bossano Prescott, E.I.; González-Juanatey, J.R. Participation and adherence to cardiac rehabilitation programs. A systematic review. Int. J. Cardiol. 2016, 223, 436–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winnige, P.; Filakova, K.; Hnatiak, J.; Dosbaba, F.; Bocek, O.; Pepera, G.; Papathanasiou, J.; Batalik, L.; Grace, S.L. Validity and Reliability of the Cardiac Rehabilitation Barriers Scale in the Czech Republic (CRBS-CZE): Determination of Key Barriers in East-Central Europe. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemps, H.M.C.; Brouwers, R.W.M.; Cramer, M.J.; Jorstad, H.T.; de Kluiver, E.P.; Kraaijenhagen, R.A.; Kuijpers, P.M.J.C.; van der Linde, M.R.; de Melker, E.; Rodrigo, S.F.; et al. Recommendations on how to provide cardiac rehabilitation services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Neth. Heart J. 2020, 28, 387–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besnier, F.; Gayda, M.; Nigam, A.; Juneau, M.; Bherer, L. Cardiac Rehabilitation During Quarantine in COVID-19 Pandemic: Challenges for Center-Based Programs. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2020, 101, 1835–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattioli, A.V.; Ballerini Puviani, M.; Nasi, M.; Farinetti, A. COVID-19 pandemic: The effects of quarantine on cardiovascular risk. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 74, 852–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepera, G.; Tribali, M.S.; Batalik, L.; Petrov, I.; Papathanasiou, J. Epidemiology, risk factors and prognosis of cardiovascular disease in the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic era: A systematic review. Rev. Cardiovasc Med. 2022, 23, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalal, H.M.; Taylor, R.S.; Jolly, K.; Davis, R.C.; Doherty, P.; Miles, J.; van Lingen, R.; Warren, F.C.; Green, C.; Wingham, J.; et al. The effects and costs of home-based rehabilitation for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: The REACH-HF multicentre randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2019, 26, 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, L.; Sharp, G.A.; Norton, R.J.; Dalal, H.; Dean, S.G.; Jolly, K.; Cowie, A.; Zawada, A.; Taylor, R.S. Home-based versus centre-based cardiac rehabilitation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 6, CD007130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanakis, M.; Batalik, L.; Papathanasiou, J.; Dipla, L.; Antoniou, V.; Pepera, G. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation programs in the era of COVID-19: A critical review. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 22, 1143–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, K.; Khonsari, S.; Gallagher, R.; Gallagher, P.; Clark, A.M.; Freedman, B.; Briffa, T.; Bauman, A.; Redfern, J.; Neubeck, L. Telehealth interventions for the secondary prevention of coronary heart disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2019, 18, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neubeck, L.; Lowres, N.; Benjamin, E.J.; Freedman, S.B.; Coorey, G.; Redfern, J. The mobile revolution—Using smartphone apps to prevent cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2015, 12, 350–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.J.; Yu, D.S.F.; Paguio, J.T. Effect of eHealth cardiac rehabilitation on health outcomes of coronary heart disease patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2020, 76, 754–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandhi, S.; Chen, S.; Hong, L.; Sun, K.; Gong, E.; Li, C.; Yan, L.L.; Schwalm, J.D. Effect of Mobile Health Interventions on the Secondary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Can. J. Cardiol. 2017, 33, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batalik, L.; Filakova, K.; Batalikova, K.; Dosbaba, F. Remotely monitored telerehabilitation for cardiac patients: A review of the current situation. World J. Clin. Cases 2020, 8, 1818–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batalik, L.; Pepera, G.; Papathanasiou, J.; Rutkowski, S.; Líška, D.; Batalikova, K.; Hartman, M.; Felšőci, M.; Dosbaba, F. Is the Training Intensity in Phase Two Cardiovascular Rehabilitation Different in Telehealth versus Outpatient Rehabilitation? J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, J.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Schmid, C.H. Quantitative synthesis in systematic reviews. Ann. Intern. Med. 1997, 127, 820–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Jüni, P.; Moher, D.; Oxman, A.D.; Savović, J.; Schulz, K.F.; Weeks, L.; Sterne, J.A.C. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011, 343, d5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cai, C.; Bao, Z.; Wu, N.; Wu, F.; Sun, G.; Yang, G.; Chen, M. A novel model of home-based, patient-tailored and mobile application-guided cardiac telerehabilitation in patients with atrial fibrillation: A randomised controlled trial. Clin. Rehabil. 2021, 36, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddison, R.; Rawstorn, J.C.; Stewart, R.A.H.; Benatar, J.; Whittaker, R.; Rolleston, A.; Jiang, Y.; Gao, L.; Moodie, M.; Warren, I.; et al. Effects and costs of real-time cardiac telerehabilitation: Randomised controlled non-inferiority trial. Heart 2019, 105, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, R.; Bruning, J.; Morris, N.R.; Mandrusiak, A.; Russell, T. Home-based telerehabilitation is not inferior to a centre-based program in patients with chronic heart failure: A randomised trial. Clin. Rehabil. 2017, 63, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kraal, J.J.; Van den Akker-Van Marle, M.E.; Abu-Hanna, A.; Stut, W.; Peek, N.; Kemps, H.M.C. Clinical and cost-effectiveness of home-based cardiac rehabilitation compared to conventional, centre-based cardiac rehabilitation: Results of the FIT@Home study. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2017, 24, 1260–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederix, I.; Hansen, D.; Coninx, K.; Vandervoort, P.; Vandijck, D.; Hens, N.; Van Craenenbroeck, E.; Van Driessche, N.; Dendale, P. Medium-Term Effectiveness of a Comprehensive Internet-Based and Patient-Specific Telerehabilitation Program with Text Messaging Support for Cardiac Patients: Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2015, 17, e185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piotrowicz, E.; Zieliłski, T.; Bodalski, R.; Rywik, T.; Dobraszkiewicz-Wasilewska, B.; Sobieszczałska-Małek, M.; Stepnowska, M.; Przybylski, A.; Browarek, A.; Szumowski, ł.; et al. Home-based telemonitored Nordic walking training is well accepted, safe, effective and has high adherence among heart failure patients, including those with cardiovascular implantable electronic devices: A randomised controlled study. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2015, 22, 1368–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snoek, J.A.; Prescott, E.I.; van der Velde, A.E.; Eijsvogels, T.M.H.; Mikkelsen, N.; Prins, L.F.; Bruins, W.; Meindersma, E.; González-Juanatey, J.R.; Peña-Gil, C.; et al. Effectiveness of Home-Based Mobile Guided Cardiac Rehabilitation as Alternative Strategy for Nonparticipation in Clinic-Based Cardiac Rehabilitation Among Elderly Patients in Europe: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2021, 6, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skobel, E.; Knackstedt, C.; Martinez-Romero, A.; Salvi, D.; Vera-Munoz, C.; Napp, A.; Luprano, J.; Bover, R.; Glöggler, S.; Bjarnason-Wehrens, B.; et al. Internet-based training of coronary artery patients: The Heart Cycle Trial. Heart Vessel. 2017, 32, 408–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo-Escobar, R.; González-Represas, A.; Gómez-González, A.M.; Montiel-Trujillo, A.; Aguilar-Jimenez, R.; Carrasco-Ruíz, R.; Salinas-Sánchez, P. Effectiveness and safety of a home-based cardiac rehabilitation programme of mixed surveillance in patients with ischemic heart disease at moderate cardiovascular risk: A randomised, controlled clinical trial. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2017, 17, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Song, Y.; Ren, C.; Liu, P.; Tao, L.; Zhao, W.; Gao, W. Effect of Smartphone-Based Telemonitored Exercise Rehabilitation among Patients with Coronary Heart Disease. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2020, 13, 659–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Batalik, L.; Dosbaba, F.; Hartman, M.; Batalikova, K.; Spinar, J. Benefits and effectiveness of using a wrist heart rate monitor as a telerehabilitation device in cardiac patients: A randomized controlled trial. Medicine 2020, 99, e19556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila, A.; Claes, J.; Buys, R.; Azzawi, M.; Vanhees, L.; Cornelissen, V. Home-based exercise with telemonitoring guidance in patients with coronary artery disease: Does it improve long-term physical fitness? Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2020, 27, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avila, A.; Claes, J.; Goetschalckx, K.; Buys, R.; Azzawi, M.; Vanhees, L.; Cornelissen, V. Home-Based Rehabilitation with Telemonitoring Guidance for Patients with Coronary Artery Disease (Short-Term Results of the TRiCH Study): Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018, 20, e225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dehghani, M.; Cheraghi, M.; Namdari, M.; Roshan, V.D. Effects of Phase IV Pedometer Feedback Home-Based Cardiac Rehabilitation on Cardiovascular Functional Capacity in Patients With Myocardial Infarction: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Basic. Sci. Med. 2019, 4, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Bank W.D.I. The World by Income and Region. Available online: https://datatopics.worldbank.org/world-development-indicators/the-world-by-income-and-region.html (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Zwisler, A.D.; Norton, R.J.; Dean, S.G.; Dalal, H.; Tang, L.H.; Wingham, J.; Taylor, R.S. Home-based cardiac rehabilitation for people with heart failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Cardiol. 2016, 221, 963–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, H.J.; Jiang, Y.; Tam, W.W.S.; Yeo, T.J.; Wang, W. Effectiveness of home-based cardiac telerehabilitation as an alternative to Phase 2 cardiac rehabilitation of coronary heart disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2021, 29, 1017–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanakis, M.; Batalik, L.; Antoniou, V.; Pepera, G. Safety of home-based cardiac rehabilitation: A systematic review. Heart Lung 2022, 55, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawstorn, J.C.; Gant, N.; Direito, A.; Beckmann, C.; Maddison, R. Telehealth exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart 2016, 102, 1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ke, Q.Q.; Su, J.K.; Yang, Q.H. Mobilizing artificial intelligence to cardiac telerehabilitation. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 23, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, M.S.; Sit, J.W.H.; Karthikesu, K.; Chair, S.Y. Effectiveness of technology-assisted cardiac rehabilitation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021, 124, 104087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotakos, D.; Notara, V.; Kouvari, M.; Pitsavos, C. The Mediterranean and other Dietary Patterns in Secondary Cardiovascular Disease Prevention: A Review. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2016, 14, 442–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author (Year) Country | Study Design | Population (P): a. Number of Participants (n) b. Diagnosis c. Age (Mean ±SD) d. Female, n (%) | Intervention (I): a. Number (n) b. Duration/Frequency (Per Week) c. Intervention Outline d. PA Prescription | Control (C): a. Number (n) b. Outline | Wearable Sensors | Outcome (O): a. Primary b. Secondary | Remarks: a. Attrition b. ITT c. MDM d. Protocol e. Funding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avila et al. (2018)/Belgium [42] | Three-arm parallel RCT | a. n = 90 b. CAD, previous MI c. Sample: 61.2 ± 7.6 HB-CRG: 58.6 ± 13 CB-CRG: 61.9 ± 7.3 CG: 61.7 ± 7.7 d. HB-CRG: 4 (13) CB-CRG: 3 (10) CG: 3 (10) | HB-CRG a. n = 30 b. 12 weeks/6–7 days per week c. 3 supervised sessions for individualized exercise prescription before the intervention, use of the sensors and data uploading procedures. Weekly feedback via phone or email d. at least 150 min of exercise/week at 70–80% of HRR. CB-CRG a. n = 30 b. 12 weeks/3 sessions per week c. 3 exercise sessions at an outpatient clinic d. ~150 min of endurance training (2 × 7 min of cycling, 2 × 7 min of treadmill walking/running, 7 min of arm ergometry or rowing, and 2 × 7 min of dynamic calisthenics) and relaxation. Exercise load adjusted to target HR (70–80% of the HRR). | a. n = 30 b. CG: usual care (counseling to remain physically active). | HR monitor (Garmin Forerunner 210, Wichita USA) Accelerometer Sensewear Mini Armband (BodyMedia, Inc., Pittsburgh, PA, USA). | a. Cardiorespiratory fitness symptom-limited CPET (VO2max). b. PA, lipid profile, muscle strength and endurance, HOMA index. | a. HB-CRG:2 CG:4 b. Yes c. Yes d. NR e. Yes |

| Avila et al. (2020)/Belgium [41] | Three-arm parallel RCT | a. n = 80 b. CAD, previous MI c. HB-CRG: 62.2 ± 7.1 CB-CRG: 62.0 ± 7.4 CG: 63.7 ±7.4 d. HB-CRG: 3 (12%) CB-CRG: 3 (10%) CG: 2 (08%) | a. n (HB-CRG):26 n (CB-CRG): 29 b. 9-month follow-up of Avila et al. (2018) study. Solely counseling to remain physically active to all study groups. Accelerometer use for a minimum of five consecutive days. | a. n (CG): 25 b. CG: usual care (counseling to remain physically active). | Accelerometer Sensewear Mini Armband (BodyMedia, Inc., Pittsburgh, PA, USA). | a. Cardiorespiratory fitness symptom-limited CPET (VO2max). b. PA, lipid profile, muscle function, QoL. | a. HB-CRG:4 CB-CR:1 CG:5 b. No c. No d. NR e. Yes |

| Batalik et al. (2020)/Czech Republic [40] | Single prospective RCT | a. n = 56 b. CVD (MI, angina, MI, CRV) c. ITG: 56.5 ± 6.9 ROT: 57.7 ± 7.6 d. ITG: 4 (15%) ROT: 5 (20%) | a. n = 28 b. 12 weeks/3 sessions per week c. 2 supervised training sessions in the outpatient clinic before home intervention. Once/a week, feedback provided d. 3 sessions/week of 10′ warm-up, 60′ aerobic phase (walking or cycling) at moderate rate (70–80% of HRR) and 10′ cool-down. | a. n = 28 b. 12 weeks/3 sessions per week. Supervised exercise workout in an outpatient clinic (10′ warm-up, 60′ aerobic phase (cycling on ergometers and walking on treadmill)/week at 70–80% of HRR) and 10 min cool-down). | Wrist HR monitor M430 (Polar, Kempele, Finland). | a. Physical fitness symptom-limited CPET (VO2max). b. QoL, adherence. | a. ITG:2 ROT:3 b. No c. No d. Yes e. Yes |

| Bravo-Escobar et al. (2017)/Spain [38] | Multicenter RCT | a. n = 28 b. CAD (ICM with CRV) c. Hospital: 55.64 ± 11.35 Home: 56.50 ± 6.01 d. Hospital: 0 (0%) Home: 0 (0%) | a. n = 14 b. 2 months/3 sessions per week c. supervised exercise session in the CR unit once a week combined with an 1 h home walking program for at least two more days a week. Once a week strength-training and health education session at the hospital and group psychotherapy. d. 3 sessions of 1 h at 70% (1st month) and 80% (2nd month)of the HRR | a. n = 14 b. 2 months/3 exercise sessions per week of 1 h at 70% (1st month) and 80% (2nd month) of the HRR in an outpatient clinic, counseling for further exercising at home. Once a week: strength-training, health education session at the hospital and group psychotherapy. | Remote ECG monitoring device NUUBO®. | a. Exercise capacity (exertion test), SBP, DBP, lipid profile, QoL, adverse events. | a. Hospital: 0 Home: 1 b. No c. No d. No e. Yes |

| Cai et al. (2021)/China [30] | Single-center, prospective RCT | a. n = 100 b. RFCA c. IG:57 ± 11 CG: 57 ± 9 d. IG: 18 (36.7%) CG: 16 (33.3%) | a. n = 50 b. 12 weeks/5 times per week c. aerobic training. Mobile application-guidance and device telemonitoring. d. 5 sessions of 65 min each at HR target and HR alarm. | a. n = 50 b. 12 weeks/5 sessions of 65 min each at HR target and HR alarm per week: standard treatment, aerobic training. | ShuKang app (Recovery Plus Inc., China). Portable ECG recording device. | a. Physical fitness symptom-limited CPET (VO2max). b. PA (IPAQ), adherence, health beliefs, self-efficacy. | a. IG:1 CG:2 b. No c. No d. Yes e. No |

| Dehghani et al. (2019)/Iran [43] | a. n = 40 b. MI c. MIG: 51.4 ± 7.97 MCG:51.1 ± 7.86 FIG: 51.5 ± 6.96 FCG: 53 ± 7.33 d. 20 (50%) | a. n = 10 (male), n = 10 (female) b. 8 weeks/5 times per week. c. 2 IGs: male/female participants. Walking exercise program with step counter feedback. d. 5 sessions of 45′–60′ duration (7′ warm-up, 40′ walking, 7′ recovery and stretching exercises) at the 11–13 Borg scale. 10% increase in number of steps/week | a. n = 10 (male), n = 10 (female). b. 8 weeks/5 sessions of 45′-60′ duration (7′ warm-up, 40′ walking, 7′ recovery and stretching exercises) at the 11–13 Borg scale. 10% per week: walking exercise program without step counter feedback. | NR | a. Functional capacity (treadmill test): METs, VO2max, total time, HRmax and distance travelled during treadmill testing. | a. IGs:0 CGs:0 b. No c. No d. NR e. Yes | |

| Frederix et al. (2015)/Belgium [34] | Multicenter, prospective RCT | a. n = 140 b. CR patients c. IG: 61 ± 9 CG: 61 ± 8 d. IG: 10 (14%) CG: 15 (21%) | a. n = 70 b. 24 weeks/2 times per week c. 12 weeks CBCR and 24 weeks telerehabilitation program (starting from the 6th week of the CBCR). Aerobic training, dietary/smoking cessation/PA guidance. Feedback once weekly (email/SMS). d. 2 sessions of 45′–60′/session at HR target and/or workload, of an intensity at VO2max (as achieved in baseline CPET) and calculated BMI. | a. n = 70 b. 12 weeks/2 sessions of 45′–60′/session at HRtarget and/or workload of an intensity between their VT1 and RCP: endurance training (walking/running and/or cycling and arm cranking). Consultation with dietician and psychologist at the rehabilitation center. | Yorbody accelerometer Belgium. | a. Vo2max(CPET). b. PA (accelerometer, IPAQ), lipid profile, HbA1c, QoL. | a. IG:1 CG:0 b. Yes, except 1 (non CVD pathology) c. No d. Yes e. Yes |

| Hwang et al. (2017)/Australia [32] | Two-group, parallel, non-inferiority RCT | a. n = 53 b. Chronic HF) c. IG: 68 ± 14 CG: 67 ± 11 d. IG: 5 (21%) CG: 8 (28%) | a. n = 24 b. 12 weeks/2 times per week. c. Group-based telerehabilitation with real time. Report of BP, HR and oxygen saturation levels and 15′ educational interactions at the start of each exercise session. d. 60′ of exercise/session (10′ warm-up, 40′ aerobic and strength exercises, and 10′ cool-down). Exercise intensity commenced at 9 (very light) and gradually progressed towards 13 (somewhat hard) on Borg scale. | a. n = 29 b. 12 weeks/2 exercise sessions of 60′ per week: aerobic training, education sessions at the hospital. Exercise intensity commenced at 9 (very light) and gradually progressed towards 13 (somewhat hard) on Borg scale. | Automatic sphygmanometer, finger pulse oximeter. | a. Functional capacity (6 MWT). b. Balance tests (BOOMER), 10MWT, strength (grip, quadriceps), urinary incontinence, quality of life (MLWHFQ, EQ-5D), patient satisfaction(CSQ-8), attendance rates, adverse events. | a. IG:1 CG:3 b. NR c. NR d. Yes e. Yes |

| Kraal et al. (2017)/Netherlands [33] | Prospective RCT | a. n = 90 b. CR patients after ACS or PCI or CABG c. IG: 60.5 ± 8.8 CG: 57.7 ± 8.7 d. IG: 5 (11%) CG: 5 (11%) | a. n = 45 b. 12 weeks/at least two training sessions a week c. 3 supervised training sessions in the outpatient clinic. Once a week telephone feedback on training modalities. Motivational Interviewing. d. 2 sessions of 45–60 min each at an intensity of 70–85% of the HRmax as assessed during the CPET at baseline | a. n = 45 b. 12 weeks/2 group-based, supervised training sessions (cycle ergometer, treadmill) of 45′–60′each at an intensity of 70–85% of the HRmax as assessed during the baseline assessment in the outpatient clinic. | HR monitor (Garmin FR70) Triaxial accelerometer (ActiGraph wGT3Xþ monitor). | a. PeakVO2 (CPET), PA (PAEE, PAL). b. QoL(SF-36), patient satisfaction (Consumer Quality Index), psychosocial status (HADS, PHQ), training adherence and cost effectiveness. | a. IG:8 CG:4 b. yes c. NR d. yes e. yes |

| Maddison et al. (2019)/New Zealand [31] | Two-arm RCT | a. n = 162 b. CHD (MI, angina, CRV) c. IG: 61.0 ± 13.2 CG: 61.5 ± 12.2 d. IG: 13 (15.9%) CG: 10 (12.5%) | a. n = 82 b. 12 weeks/3 week c. monitored exercise and remote real –time coaching provision on REMOTE-CR platform Theory-based education content delivered via SMS. d. 3 exercise sessions/week and encouragement to be active >5 days/week of 30′ to 60′ at an intensity of 40–65% HRR. | a. n = 80. b. Supervised exercise sessions in CR clinics. | Wearable sensor (BioHarness 3, Zephyr Technology, USA): HR and respiratory rates, single lead ECG and accelerometry Accelerometer Actigraph (GT1M, ActiGraph Corp, USA). | a. Symptom-limited CPET (VO2max). b. PA, SBP/DBP, BMI, lipid profile, BG, QoL(EQ-5D), cost effectiveness. | a. IG:17 CG:11 b. No c. Yes d. Yes e. Yes |

| Piotrowicz et al. (2015)/Poland [33] | Single-center, prospective, parallel-group RCT | a. n = 111 b. HF c. IG: 54.4 ± 10.9 CG: 62.1 ± 12.5 d. IG: 11 (15%) CG: 1 (3%) | a. n = 77 b. 8 weeks/5 times per week c. 3–6 monitored exercise training sessions before the intervention. Telemonitored and telesupervised Nordic Walking(NW) with the use of EHO mini device (electrocardiogram data). Psychological support via telephone. d. 5 sessions of 5′–10′ warm-up (breathing and light resistance exercises, calisthenics), a 15′–45′ NW training, and a 5′ cool-down. Training intensity set according to RPE and the training HR range (40–70% HRR). | a. n = 34. b. No guided exercise training. Only consultation for suitable lifestyle changes and self-management according to guidelines. | EHO mini device—ECG data recorder (Pro Plus Company, Poland). | a. Functional capacity—VO2max (CPET). b. Effectiveness of rehabilitation (workload duration in CPET, 6MWT distance, QoL), safety, adherence, acceptance of telemonitoring. | a. IG:2 CG:1 b. NR c. NR d. NR e. Yes |

| Skobel et al. (2017)/Germany [37] | A prospective, international, multi-center RCT | a. n = 118 b. CAD referred for CR c. IG: 60 ± 50.65 CG: 58 ± 52.67 d. IG: 5 (9%) CG: 8 (13%) | a. n = 55 b. 6 months/NR c. Training under guidance of the GEx system. Exercise prescriptions continuously reviewed and adjusted as needed. d. Endurance training (cycling, walking) and resistance training at a predefined HRtarget zone. | a. n = 63. b. 6 months/NR, report of daily physical activities on a paper dairy. | GEX system: info on medical profile, educational material and motivational feedback, sensor for acquisition of vital signs for immediate feedback with respect to training intensity. | a. Physical capacity (CPET). b. Compliance, fear, anxiety (HADS), QoL(EQ-5D), BP, EF, LDL. | a. IG:36 CG:21 b. No c. No d. NR e. Yes |

| Snoek et al. (2021)/Netherlands [36] | Multicenter, parallel RCT | a. n = 179 b. HF 54.4 ± 10.9 c. IG: 72.4 ± 5.4 CG: 73.6 ± 5.5 d. IG: 20 (22%) CG: 14 (16%) | a. n = 89 b. 6 months/5 days per week. c. HBCR exercise training. Use of smartphone application to capture training modalities. Motivational interviewing applied by telephone: weekly in the 1st month, every other week in the 2nd month, and monthly until completion. d. 5 sessions of 30′ moderate intensity exercise training. | a. n = 90. b. No provision of CR, only standard care. | MobiHealth BV smartphone application. HR belt. | a. Physical fitness: VO2peak (CPET). b. PA, lipid profile, HbA1c, adverse events, QoL(SF-36v2), depression (PHQ-9) mortality, hospitalization. | a. IG:6 CG:2 b. Yes c. Yes d. Yes e. Yes |

| Song et al. (2020)/China [39] | Two-arm RCT | a. n = 106 b. Stable CHD c. IG: 54.17 ± 8.76 CG: 54.83 ± 9.13 d. IG: 5 (10.4%) CG: 8 (16.7%) | a. n = 53 b. 6 months/3–5 times per week. c. Telemonitored HR during PA. Feedback on patients’ exercise frequency/intensity, BP, and HR before and after exercise. Feedback via SMS and telephone call. d. 3–5 sessions of 30′ at an intensity set at HR at aerobic threshold. | a. n = 53. b. Usual care (routine discharge education and outpatient follow-up). | HR belts (Suunto). | a. Exercise tolerance-symptom-limited CPET (VO2peak). b. SBP/DBP, lipid profile. | a. IG:5 CG:5 b. NR c. NR d. Yes e. Yes |

| Author/Year | Baseline/Follow Up at …. | Primary Measure/Outcome Values: From Baseline at Follow Up | Secondary Measures/Outcome Values: From Baseline at Follow Up |

|---|---|---|---|

| Avila et al. (2018) [42] | 6 months | Cardiorespiratory fitness

and center-based group: from 25.4 (7.32) at 26.7 (7.90).

and center-based group: from 19.5 (1.04) at 20.4 (1.04).

Improved in home–based group: from 24.9 (5.25) at 26.3 (6.98) and center-based group: from 22.7 (6.95) at 24.2 (7.13). | Physical activity

Strength/Endurance

(P-interaction = 0.57), the physical (P-interaction = 0.50) and mental (P-interaction = 0.85) composite scores. Adherence

|

| Avila et al. (2020) [41] | 12 months | Cardiorespiratory fitness

| Physical Activity

Strength/Endurance

Cardiovascular risk factors

Quality of Life

|

| Batalik et al. (2020) [40] | 12 weeks | Physical Fitness

| Quality of Life

Adherence

|

| Bravo-Escobar et al. (2017) [38] | 2 months | Physical Fitness

| Quality of Life

Adverse events

|

| Cai et al. (2021) [30] | 12 weeks | Physical Fitness

| Physical Activity

Health Beliefs

Adherence

|

| Dehghani et al. (2019) [43] | 8 weeks | Functional Capacity

| |

| Frederix et al. (2015) [34] | 6 months 2 years | Aerobic Capacity

No changes in the CG after 24 weeks when compared to baseline (p = 0.09) and decreased from week 6 (22.86 ± 0.66) to week 24 (22.15 ± 0.77), p = 0.02. | Physical Activity

Summed leisure VMW increased significantly in the IG (based on Friedman’s test, χ22 = 13.7, p = 0.01). No changes in the IG (based on Friedman’s test, χ22 = 13.7, p = 0.01). Significant between-group difference, in favor of the IG (U = 1830, z = 3.336, p = 0.01).Total sitting time decreased significantly in the IG (based on Friedman’s test, χ22 = 19.9, p < 0.001).Cardiovascular Risk Factors

Health-Related Quality of Life

|

| Hwang et al. (2017) [32] | 12 weeks 24 weeks | Aerobic capacity—6MWD. No significant between-group differences. | No significant between-group differences in balance and muscle strength, QoL. Adherence

Adverse events

|

| Kraal et al. (2017) [33] | 12 weeks 1 year | Physical fitness

| Physical Activity

Quality of Life

Anxiety

Depression

Adherence

|

| Maddison et al. (2019) [31] | 12 weeks 24 weeks | Physical Fitness

| Physical Activity

BMI

Cost Evaluation

|

| Piotrowicz et al. (2015) [33] | 8 weeks | Physical Fitness

| Effectiveness of rehabilitation

|

| Skobel et al. (2017) [37] | 6 months | Physical Fitness

| QoL, BMI, HR rest, laboratory parameters: no statistical significant changes. |

| Snoek et al. (2021) [36] | 6 months | Physical Fitness

| Physical Activity

Cardiovascular biomarkers

Hospitalization

|

| Song et al. (2020) [39] | 6 months | Exercise tolerance

| No statistically significant outcomes |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Antoniou, V.; Davos, C.H.; Kapreli, E.; Batalik, L.; Panagiotakos, D.B.; Pepera, G. Effectiveness of Home-Based Cardiac Rehabilitation, Using Wearable Sensors, as a Multicomponent, Cutting-Edge Intervention: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3772. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11133772

Antoniou V, Davos CH, Kapreli E, Batalik L, Panagiotakos DB, Pepera G. Effectiveness of Home-Based Cardiac Rehabilitation, Using Wearable Sensors, as a Multicomponent, Cutting-Edge Intervention: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2022; 11(13):3772. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11133772

Chicago/Turabian StyleAntoniou, Varsamo, Constantinos H. Davos, Eleni Kapreli, Ladislav Batalik, Demosthenes B. Panagiotakos, and Garyfallia Pepera. 2022. "Effectiveness of Home-Based Cardiac Rehabilitation, Using Wearable Sensors, as a Multicomponent, Cutting-Edge Intervention: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 11, no. 13: 3772. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11133772

APA StyleAntoniou, V., Davos, C. H., Kapreli, E., Batalik, L., Panagiotakos, D. B., & Pepera, G. (2022). Effectiveness of Home-Based Cardiac Rehabilitation, Using Wearable Sensors, as a Multicomponent, Cutting-Edge Intervention: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 11(13), 3772. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11133772