Elevated Baseline Serum PD-L1 Level May Predict Poor Outcomes from Breast Cancer in African-American and Hispanic Women

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Human Subjects

2.2. Demographic and Clinical Information

2.3. Serum PD-L1 and Cytokine Levels

2.4. PTEN, pAkt, CD44, and CD24 Expression in Breast Cancer Tissue

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

3.2. PD-L1 Serum Level in African-American and Hispanic Women with and without Breast Cancer

3.3. Serum PD-L1 Level Is Higher in HER2+ and TNBC

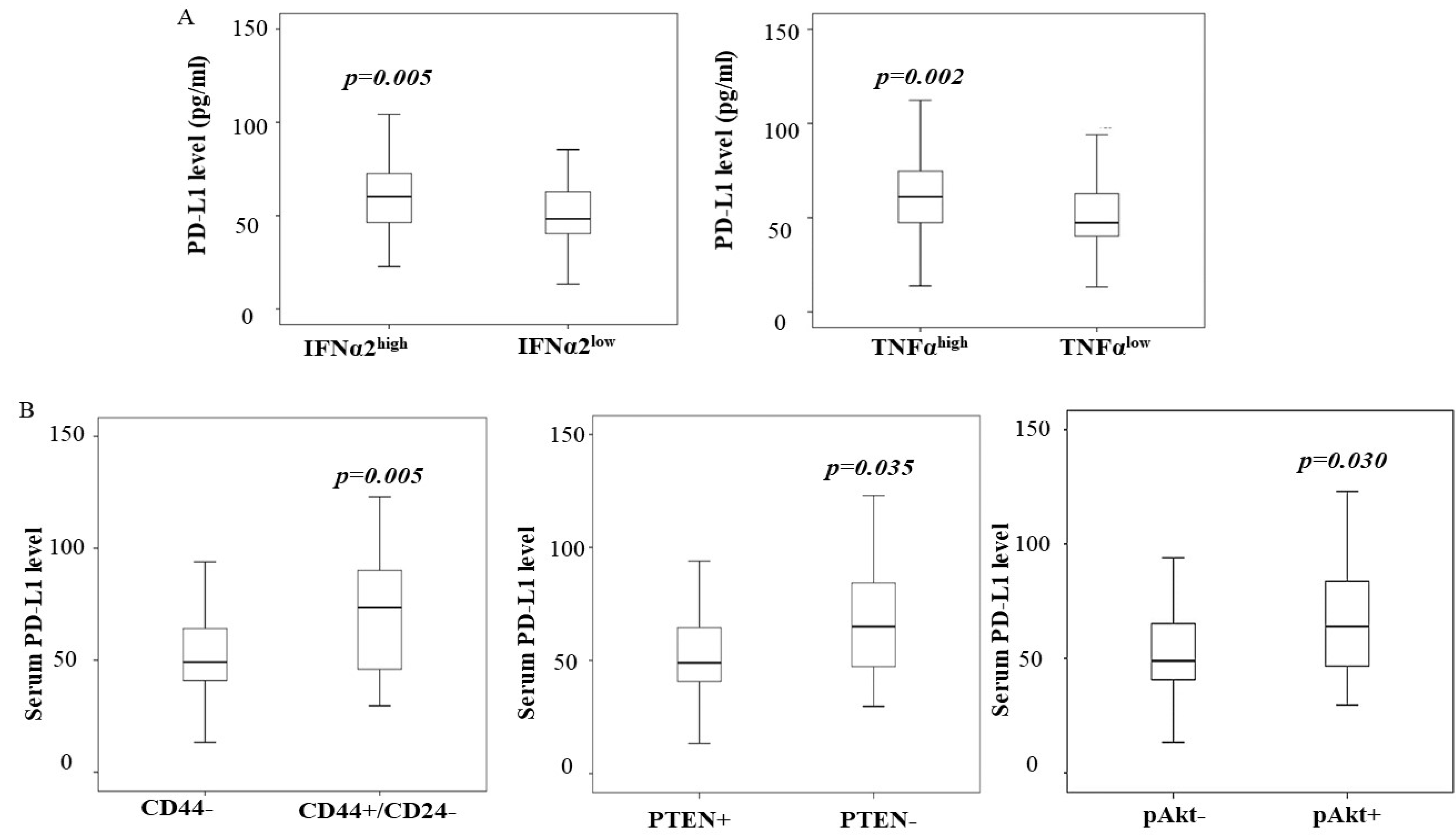

3.4. Increased PD-L1 in Breast Cancer Is Associated with High Levels of IFNα2 and TNFα

3.5. A High Level of PD-L1 Is Associated with PTEN Loss and Cancer Stem-like Phenotype

3.6. PD-L1 Serum Level Predicts Disease-Free Survival in Breast Cancer

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures. 2020. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2020/cancer-facts-and-figures-2020.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Parise, C.A.; Caggiano, V. Breast Cancer Survival Defined by the ER/PR/HER2 Subtypes and a Surrogate Classification according to Tumor Grade and Immunohistochemical Biomarkers. J. Cancer Epidemiol. 2014, 2014, 469251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Sarkissyan, M.; Elshimali, Y.; Vadgama, J.V. Triple-Negative Breast Tumors in African-American and Hispanic/Latina Women Are High in CD44+, Low in CD24+, and Have Loss of PTEN. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e78259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Voduc, K.D.; Cheang, M.C.; Tyldesley, S.; Gelmon, K.; Nielsen, T.O.; Kennecke, H. Breast cancer subtypes and the risk of local and regional relapse. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 1684–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scott, L.C.; Mobley, L.R.; Kuo, T.M.; Il’yasova, D. Update on triple-negative breast cancer disparities for the United States: A population-based study from the United States Cancer Statistics database, 2010 through 2014. Cancer Med. 2019, 8, 3389–3400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogel, C.L.; Cobleigh, M.A.; Tripathy, D.; Gutheil, J.C.; Harris, L.N.; Fehrenbacher, L.; Slamon, D.J.; Murphy, M.; Novotny, W.F.; Burchmore, M.; et al. Efficacy and safety of trastuzumab as a single agent in first-line treatment of HER2-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2002, 20, 719–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clayton, A.J.; Danson, S.; Jolly, S.; Ryder, W.D.J.; Burt, P.A.; Stewart, A.L.; Wilkinson, P.M.; Welch, R.S.; Magee, B.; Wilson, G.; et al. Incidence of Cerebral Metastases in Patients Treated with Trastuzumab for Metastatic Breast Cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2004, 91, 639–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohlmann, P.R.; Mayer, I.A.; Mernaugh, R. Resistance to Trastuzumab in Breast Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 7479–7791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Riella, L.V.; Paterson, A.M.; Sharpe, A.H.; Chandraker, A. Role of the PD-1 pathway in the immune response. Am. J. Transplant. 2012, 12, 2575–2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francisco, L.M.; Sage, P.T.; Sharpe, A.H. The PD-1 pathway in tolerance and autoimmunity. Immunol. Rev. 2010, 236, 219–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephen, B.; Hajjar, J. Overview of Basic Immunology and Translational Relevance for Clinical Investigators. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2018, 995, 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe, A.H.; Wherry, E.J.; Ahmed, R.; Freeman, G.J. The function of programmed cell death 1 and its ligands in regulating autoimmunity and infection. Nat. Immunol. 2007, 8, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, J.; Wang, D.; Zhang, G.; Guo, X. The Role of PD-1/PD-L1 Axis in Treg Development and Function: Implications for Cancer Immunotherapy. Onco Targets Ther. 2019, 12, 8437–8445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Velcheti, V.; Schalper, K.A.; Carvajal, D.E.; Anagnostou, V.K.; Syrigos, K.N.; Sznol, M.; Herbst, R.S.; Gettinger, S.N.; Chen, L.; Rimm, D.L. Programmed death ligand-1 expression in non-small cell lung cancer. Lab. Investig. 2014, 94, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Yu, Z.; Xiang, R.; Li, C.; Wang, L.; Chen, X.S.; Li, Q.; Chen, M.; Wang, L. Correlation between infiltration of FOXP3+ regulatory T cells and expression of B7-H1 in the tumor tissues of gastric cancer. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2014, 96, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, S.J.; Wang, L.J.; Wang, G.D.; Guo, Z.Y.; Wei, M.; Menget, Y.L.; Yang, A.G.; Wen, W.H. B7-H1 expression is associated with poor prognosis in colorectal carcinoma and regulates the proliferation and invasion of HCT116 colorectal cancer cells. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e76012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ohigashi, Y.; Sho, M.; Yamada, Y.; Tsurui, Y.; Hamada, K.; Ikeda, N.; Mizuno, T.; Yoriki, R.; Kashizuka, H.; Yane, K.; et al. Clinical significance of programmed death-1 ligand-1 and programmed death-1 ligand-2 expression in human esophageal cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005, 11, 2947–2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Geng, L.; Huang, D.; Liu, J.; Qian, Y.; Deng, J.; Li, D.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, G.; Zheng, S. B7-H1 upregulated expression in human pancreatic carcinoma tissue associates with tumor progression. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 134, 1021–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Teng, F.; Kong, L.; Yu, J. PD-L1 expression in human cancers and its association with clinical outcomes. Onco Targets Ther. 2016, 9, 5023–5039. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, P.; Wu, D.; Li, L.; Chai, Y.; Huang, J. PD-L1, and Survival in Solid Tumors: A Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0131403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muenst, S.; Schaerli, A.R.; Gao, F.; Däster, S.; Trella, E.; Droeser, R.A.; Muraro, M.G.; Zajac, P.; Zanetti, R.; Gillanders, W.E.; et al. Expression of programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) is associated with poor prognosis in human breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2014, 146, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mittendorf, E.A.; Philips, A.V.; Meric-Bernstam, F.; Qiao, N.; Wu, Y.; Harrington, S.; Su, X.; Wang, Y.; Gonzalez-Angulo, A.M.; Akcakanat, A.; et al. PD-L1 Expression in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2014, 2, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, M.; Sun, H.; Zhao, S.; Wang, Y.; Pu, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Q. Expression of PD-L1 and prognosis in breast cancer: A meta-analysis. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 31347–31354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gong, J.; Chehrazi-Raffle, A.; Reddi, S.; Salgia, R. Development of PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors as a form of cancer immunotherapy: A comprehensive review of registration trials and future considerations. J. Immunother. Cancer 2018, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planes-Laine, G.; Rochigneux, P.; Bertucci, F.; Chrétien, A.S.; Viens, P.; Sabatier, R.; Gonçalves, A. PD-1/PD-L1 Targeting in Breast Cancer: The First Clinical Evidences are Emerging—A Literature Review. Cancers 2019, 11, 1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hartkopf, A.D.; Taran, F.A.; Wallwiener, M.; Walter, C.B.; Krämer, B.; Grischke, E.M.; Brucker, S.Y. PD-1 and PD L1 Immune Checkpoint Blockade to Treat Breast Cancer. Breast Care 2016, 11, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Loi, S.; Sirtaine, N.; Piette, F.; Salgado, R.; Viale, G.; Van, E.F.; Rouas, G.; Francis, P.; Crown, J.P.A.; Hitre, E.; et al. Prognostic and predictive value of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in a phase III randomized adjuvant breast cancer trial in node-positive breast cancer comparing the addition of docetaxel to doxorubicin with doxorubicin-based chemotherapy: BIG 02–98. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 860–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loi, S.; Michiels, S.; Salgado, R.; Sirtaine, N.; Jose, V.; Fumagalli, D.; Kellokumpu-Lehtinen, P.L.; Bono, P.; Kataja, V.; Desmedt, C.; et al. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes are prognostic in triple-negative breast cancer and predictive for trastuzumab benefit in early breast cancer: Results from the FinHER trial. Ann. Oncol. 2014, 25, 1544–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, S.; Gray, R.J.; Demaria, S.; Goldstein, L.; Perez, E.A.; Shulman, L.N.; Martino, S.; Wang, M.; Jones, V.E.; Saphner, T.J.; et al. Prognostic value of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in triple-negative breast cancers from two phase III randomized adjuvant breast cancer trials: ECOG 2197 and ECOG 1199. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 2959–2966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribas, A.; Hu-Lieskovan, S. What does PD-L1 positive or negative mean? J. Exp. Med. 2016, 213, 2835–2840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cottrell, T.; Taube, J.M. PD-L1, and Emerging Biomarkers in PD-1/PD-L1 Blockade Therapy. Cancer J. 2018, 24, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinato, D.J.; Shiner, R.J.; White, S.D.T.; Black, J.R.M.; Trivedi, P.; Stebbing, J.; Sharma, R.; Mauri, F.A. Intra-tumoral heterogeneity in the expression of programmed death (PD) ligands in isogenic primary and metastatic lung cancer: Implications for immunotherapy. Oncoimmunology 2016, 5, e1213934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Patel, S.P.; Kurzrock, R. PD-L1 Expression as a Predictive Biomarker in Cancer Immunotherapy. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2015, 14, 847–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aghajani, M.J.; Roberts, T.L.; Yang, T.; McCafferty, C.E.; Caixeiro, N.J.; DeSouza, P.; Niles, N. Elevated levels of soluble PD-L1 are associated with reduced recurrence in papillary thyroid cancer. Endocr. Connect. 2019, 8, 1040–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, L.; Wang, H.; Chen, H.; Wang, W.D.; Chen, X.Q.; Geng, Q.R.; Xia, Z.J.; Lu, Y. Serum levels of soluble programmed death-ligand 1 predict treatment response and progression-free survival in multiple myeloma. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 41228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ugurel, S.; Schadendorf, D.; Horny, K.; Sucker, A.; Schramm, S.; Utikal, J.; Pföhler, C.; Herbst, R.; Schilling, B.; Blank, D.; et al. Elevated baseline serum PD-1 or PD-L1 predicts poor outcome of PD-1 inhibition therapy in metastatic melanoma. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Takahashi, N.; Iwasa, S.; Sasaki, Y.; Shoji, H.; Honma, Y.; Takashima, A.; Okita, N.T.; Kato, K.; Hamaguchi, T.; Yamada, Y. Serum levels of soluble programmed cell death ligand 1 as a prognostic factor on the first-line treatment of metastatic or recurrent gastric cancer. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 142, 1727–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, C.; Zhi, C.; Liang, W.; Wang, X.; Chen, X.; Lv, T.; Shen, Q.; Song, Y.; Lin, D.; et al. Clinical significance of PD-L1 expression in serum-derived exosomes in NSCLC patients. J. Transl. Med. 2019, 17, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nascimento, C.; Urbano, A.C.; Gameiro, A.; Ferreira, J.; Correia, J.; Ferreira, F. Serum PD-1/PD-L1 Levels, Tumor Expression and PD-L1 Somatic Mutations in HER2-Positive and Triple Negative Normal-Like Feline Mammary Carcinoma Subtypes. Cancers 2020, 12, 1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asanuma, K.; Nakamura, T.; Hayashi, A.; Okamoto, T.; Iino, T.; Asanuma, Y.; Hagi, T.; Kita, K.; Nakamura, K.; Sudo, A. Soluble programmed death-ligand 1 rather than PD-L1 on tumor cells effectively predicts metastasis and prognosis in soft tissue sarcomas. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 9077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Mohamed, H.; Chillar, R.; Clayton, S.; Slamon, D.; Vadgama, J.V. Clinical significance of Akt and HER2/neu overexpression in African-American and Latina women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2008, 10, R3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bazhin, A.V.; Ahn, K.V.; Fritz, J.; Werner, J.; Karakhanova, S. Interferon-a Up-Regulates the Expression of PD-L1 Molecules on Immune Cells Through STAT3 and p38 Signaling. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barriga, V.; Kuol, N.; Nurgali, K.; Apostolopoulos, V. The Complex Interaction between the Tumor Micro-Environment and Immune Checkpoints in Breast Cancer. Cancers 2019, 11, 1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Murciano-Goroff, Y.R.; Warner, A.B.; Wolchok, J.D. The future of cancer immunotherapy: Microenvironment-targeting combinations. Cell Res. 2020, 30, 507–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.W.; Kong, S.K.; Kim, B.S.; Kim, H.J.; Lim, H.; Noh, K.; Kim, Y.; Choi, W.J.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, Y.S. IFNγ induces PD-L1 overexpression by JAK2/STAT1/IRF-1 signaling in EBV-positive gastric carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 17810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hsu, J.M.; Xia, W.; Hsu, Y.H.; Chan, L.C.; Yu, W.H.; Cha, J.H.; Chen, C.T.; Liao, H.W.; Kuo, C.W.; Khoo, K.H.; et al. STT3-dependent PD-L1 accumulation on cancer stem cells promotes immune evasion. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, T.; Ahn, R.; Yang, K.; Zhu, X.; Fu, Z.; Morin, G.; Bramley, R.; Cliffe, N.C.; Xue, Y.; Kuasne, H.; et al. CD44 Promotes PD-L1 Expression and Its Tumor-Intrinsic Function in Breast and Lung Cancers. Cancer Res. 2020, 80, 444–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, M.R.P.; Harrison, M.E.; Hoskin, D.W. Apigenin inhibits the inducible expression of programmed death-ligand 1 by human and mouse mammary carcinoma cells. Cancer Lett. 2016, 380, 424–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrieu, G.P.; Shafran, J.S.; Smith, C.L.; Belkina, A.C.; Casey, A.N.; Jafari, N.; Denis, G.V. BET protein targeting suppresses the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway in triple-negative breast cancer and elicits an anti-tumor immune response. Cancer Lett. 2019, 465, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yang, L.; Huang, F.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, S.; Ma, L.; You, Z. Inflammatory cytokines IL-17 and TNF-α upregulate PD-L1 expression in human prostate and colon cancer cells. Immunol Lett. 2017, 184, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schmid, P.; Adams, S.; Rugo, H.S.; Schneeweiss, A.; Barrios, C.H.; Iwata, H.; Diéras, V.; Hegg, R.; Im, S.A.; Wright, G.S.; et al. Atezolizumab and Nab-Paclitaxel in Advanced Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 2108–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA Issues Alert about the Efficacy and Potential Safety Concerns with Atezolizumab Combined with Paclitaxel to Treat Breast Cancer. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-issues-alert-about-efficacy-and-potential-safety-concerns-atezolizumab-combination-paclitaxel (accessed on 30 November 2021).

| African-American (n = 150) | Hispanic (n = 244) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases (n = 112) Median (Range) | Controls (n = 38) Media (Range) | p | Cases (n = 132) Median (Range) | Controls (n = 112) Media (Range) | p | |

| Age (years) | ^ 53 (32–79) | ^^ 50 (27–70) | 0.33 | ^ 49 (28–77) | ^^ 48 (22–77) | 0.27 |

| Percentiles | ||||||

| 25 | 46 | 46 | 42 | 40 | ||

| 50 | 53 | 50 | 49 | 48 | ||

| 75 | 57 | 57 | 56 | 54 | ||

| BMI ψ | 31 (22–55) | 32 (21–52) | 0.97 | 31 (20–57) | 30 (20–53) | 0.34 |

| Percentiles | ||||||

| 25 | 28 | 29 | 27 | 27 | ||

| 50 | 31 | 31 | 31 | 30 | ||

| 75 | 38 | 38 | 35 | 35 | ||

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |||

| Obesity * | 65 (63.1) | 21 (63.6) | 66 (54.5) | 51 (50.0) | ||

| Overweight ** | 23 (22.3) | 9 (27.3) | 38 (31.4) | 37 (36.3) | ||

| Normal (BMI ≤ 25) | 15 (14.6) | 3 (9.1) | 0.68 | 17 (14.0) | 14 (13.7) | 0.66 |

| African American (n = 150) | Hispanic (n = 244) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases (n = 112) Median (Range) | Controls (n = 38) Median (Range) | p | Cases (n = 132) Median (Range) | Controls (n = 112) Median (Range) | p | |

| PD-L1 (pg/mL) | 54.4 (20.6–206.1) | 37.3 (16–78.3) | <0.001 | 62.0 (13.4–221.7) | 37.1 (13.2–87.1) | <0.001 |

| Percentiles | ||||||

| 25 | 41.2 | 32.2 | 43.5 | 29.7 | ||

| 50 | 54.4 | 37.3 | 61.9 | 37.1 | ||

| 75 | 76.6 | 44.9 | 81.5 | 50.4 | ||

| Age (years) | N Median (range) | N Median (range) | N Median (range) | N Median (range) | ||

| ≤30 | - - | 1 42.6 | 2 37.9 (26.6–49.2) | 55 4.6 (37.2–59.2) | 0.190 | |

| 31–40 | 8 51.7 (23.8–182.2) | 4 31.2 (22.9–42.4) | 0.11 | 25 57.9 (25.3–103.1) | 23 33.7 (13.2–81.8) | <0.001 |

| 41–50 | 37 53.8 (20.6–88.6) | 15 37.0 (16.0–69.8) | 0.01 | 47 58.7 (13.4–116.7) | 39 33.2 (16.2–78.1) | <0.001 |

| 51–60 | 49 48.6 (21.3–117.4) | 14 38.4 (26.6–78.3) | 0.05 | 40 64.5 (13.9–221.7) | 34 40.5 (18.1–87.1) | <0.001 |

| ≥60 | 18 62.6 (27.5–206.1) | 4 37.7 (32.3–44.3) | 0.007 | 18 65.4 (37.6–161.0) | 11 48.1 (27.2–77.5) | <0.001 |

| N Median (range) | N Median (range) | N Median (range) | N Median (range) | |||

| Obesity * | 65 56.0 (21.3–182.2) | 21 37.3 (25.1–78.3) | <0.001 | 66 64.6 (13.9–116.7) | 51 36.3 (13.2–87.1) | <0.001 |

| Overweight ** | 23 53.4 (24.3–206.1) | 9 34.5 (16.0–51.9) | 0.006 | 38 58.8 (13.4–131.4) | 37 37.1 (18.1–77.5) | <0.001 |

| Normal | 15 58.7 (23.8–117.4) | 3 44.0 (42.6–61.3) | 0.36 | 17 52.0 (26.6–161.0) | 14 38.0 (24.3–1.1) | 0.04 |

| Cases vs. Control | Cases vs. Control | |||||

| ^OR | 95% CI | p | ^ OR | 95% CI | p | |

| PD-L1 (pg/mL) | ||||||

| ≤50 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| >50 | 5.1 | 1.9–13.7 | 0.001 | 5.3 | 2.9–9.6 | <0.001 |

| Total | African-Americans | Hispanics | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N PD-L1 (pg/mL) Median (Range) | N PD-L1 (pg/mL) Median (Range) | N PD-L1 (pg/mL) Median (Range) | * p-Value | |

| Cases Controls p-Value | 244 58.3 (13.4–221.7) | 112 54.4 (20.6–206) | 132 61.9 (13.4–221.7) | 0.12 |

| 150 37.2 (13.2–81.7) | 38 37.3 (16–78.3) | 112 37.1 (13.2–87.1) | 0.82 | |

| <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| ER/PR | ||||

| Positive | 150 50.1 (13.4–221.7) | 64 47.3 (21.3–206.1) | 86 58.7 (13.4–221.7) | 0.03 |

| Negative | 94 64.3 (20.6–182.2) | 48 63.1 (20.6–182.2) | 46 66.4 (25.3–161.0) | 0.71 |

| * p-Value | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.17 | |

| HER2 | ||||

| Positive | 52 64.7 (20.6–161.0) | 20 62.7 (20.6–103.0) | 32 64.8 (25.3–161.1) | 0.21 |

| Negative | 192 56.0 (13.4–221.7) | 89 53.9 (21.3–206.1) | 103 58.7 (13.4–221.7) | 0.36 |

| * p-Value | 0.35 | 0.92 | 0.25 | |

| Tumor size | ||||

| T0-T1 | 64 58.7 (21.3–206.1) | 35 50.5 (21.3–206.1) | 29 60.3 (31.8–131.4) | 0.27 |

| T2 | 117 56.0 (13.9–221.7) | 52 53.9 (24.3–106.0) | 65 61.8 (13.9–221.7) | 0.25 |

| T3-T4 | 63 63.9 (13.4–182.2) | 25 63.4 (20.6–182.0) | 38 64.3 (13.4–139.0) | 0.87 |

| ** p-Value | 0.47 | 0.32 | 0.88 | |

| Lymph node | ||||

| Negative | 111 56.0 (13.9–206.1) | 51 54.9 (20.6–206.1) | 61 58.7 (13.9–139.0) | 0.31 |

| Positive | 122 62.2 (13.4–221.7) | 54 56.6 (24.3–182.2) | 67 64.7 (13.4–221.7) | 0.43 |

| * p-Value | 0.32 | 0.77 | 0.29 | |

| TNM staging | ||||

| I/II | 168 54.1 (13.9–206.1) | 84 50.0 (20.6–206.1) | 84 58.8 (13.9–131.4) | 0.09 |

| III/IV | 76 66.6 (13.4–221.7) | 28 69.0 (31.0–182.2) | 48 65.1 (13.4–221.7) | 0.50 |

| * p-Value | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.20 | |

| Subtype | ||||

| ER/PR+/HER2− | 128 49.1 (13.4–221.7) | 57 47.3 (21.3–206.1) | 71 52.6 (13.4–221.7) | 0.17 |

| HER2+ | 52 64.6 (20.6–161.0) | 20 62.7 (20.6–103.0) | 32 64.8 (25.3–161.0) | 0.26 |

| ER/PR−/HER2− | 64 64.0 (26.6–182.2) | 35 61.6 (26.6–182.2) | 29 66.9 (35.2–123.0) | 0.48 |

| ** p-Value | 0.003 | 0.03 | 0.064 |

| PD-L1 ≥ 79 pg/mL vs. PD-L1 < 79 pg/mL | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p | |

| Subtypes | |||

| ER/PR+/HER2− | 1 | ||

| HER2+ | 0.7 | 0.3–3.6 | 0.63 |

| TNBC | 1.4 | 0.3–7.4 | 0.71 |

| pAkt * | |||

| Low | 1 | ||

| High | 0.6 | 0.3–4.4 | 0.71 |

| PTEN | |||

| Positive | 1 | ||

| Negative | 2.9 | 0.6–15.4 | 0.65 |

| CD44high/CD24low | |||

| Negative | 1 | ||

| Positive | 7.0 | 1.5–32.1 | 0.01 |

| PDL-1 (pg/mL) | Multivariate Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| RR | 95% CI | p-Value | |

| Total ^ | |||

| PD-L1 < 58 | 1 | ||

| PD-L1: 58–79 | 3.8 | 1.9–13.9 | 0.003 |

| PD-L1 > 79 | 3.6 | 1.5–15.3 | 0.043 |

| African-American ^^ | |||

| PD-L1 < 58 | 1 | ||

| PD-L1: 58–79 | 1.1 | 0.2–5.5 | 0.927 |

| PD-L1 > 79 | 4.4 | 1.1–36.4 | 0.036 |

| Hispanic/Latina ^^ | |||

| PD-L1 < 58 | 1 | ||

| PD-L1: 58–79 | 4.3 | 1.6–23.6 | 0.001 |

| PD-L1 > 79 | 3.6 | 1.3–24.9 | 0.008 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, Y.; Dutta, P.; Clayton, S.; McCloud, A.; Vadgama, J.V. Elevated Baseline Serum PD-L1 Level May Predict Poor Outcomes from Breast Cancer in African-American and Hispanic Women. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 283. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11020283

Wu Y, Dutta P, Clayton S, McCloud A, Vadgama JV. Elevated Baseline Serum PD-L1 Level May Predict Poor Outcomes from Breast Cancer in African-American and Hispanic Women. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2022; 11(2):283. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11020283

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Yanyuan, Pranabananda Dutta, Sheilah Clayton, Amaya McCloud, and Jaydutt V. Vadgama. 2022. "Elevated Baseline Serum PD-L1 Level May Predict Poor Outcomes from Breast Cancer in African-American and Hispanic Women" Journal of Clinical Medicine 11, no. 2: 283. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11020283

APA StyleWu, Y., Dutta, P., Clayton, S., McCloud, A., & Vadgama, J. V. (2022). Elevated Baseline Serum PD-L1 Level May Predict Poor Outcomes from Breast Cancer in African-American and Hispanic Women. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 11(2), 283. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11020283