The Role of Multi-Staged Urethroplasty in Lichen Sclerosus Penile Urethral Strictures

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients Selection

2.2. Patient-Reported Outcome Measures Evaluation

- How do you rate your overall micturition quality?

- How do you rate your sexual life quality?

- How do you rate the aesthetical results?

- Are you satisfied with the general surgical results?

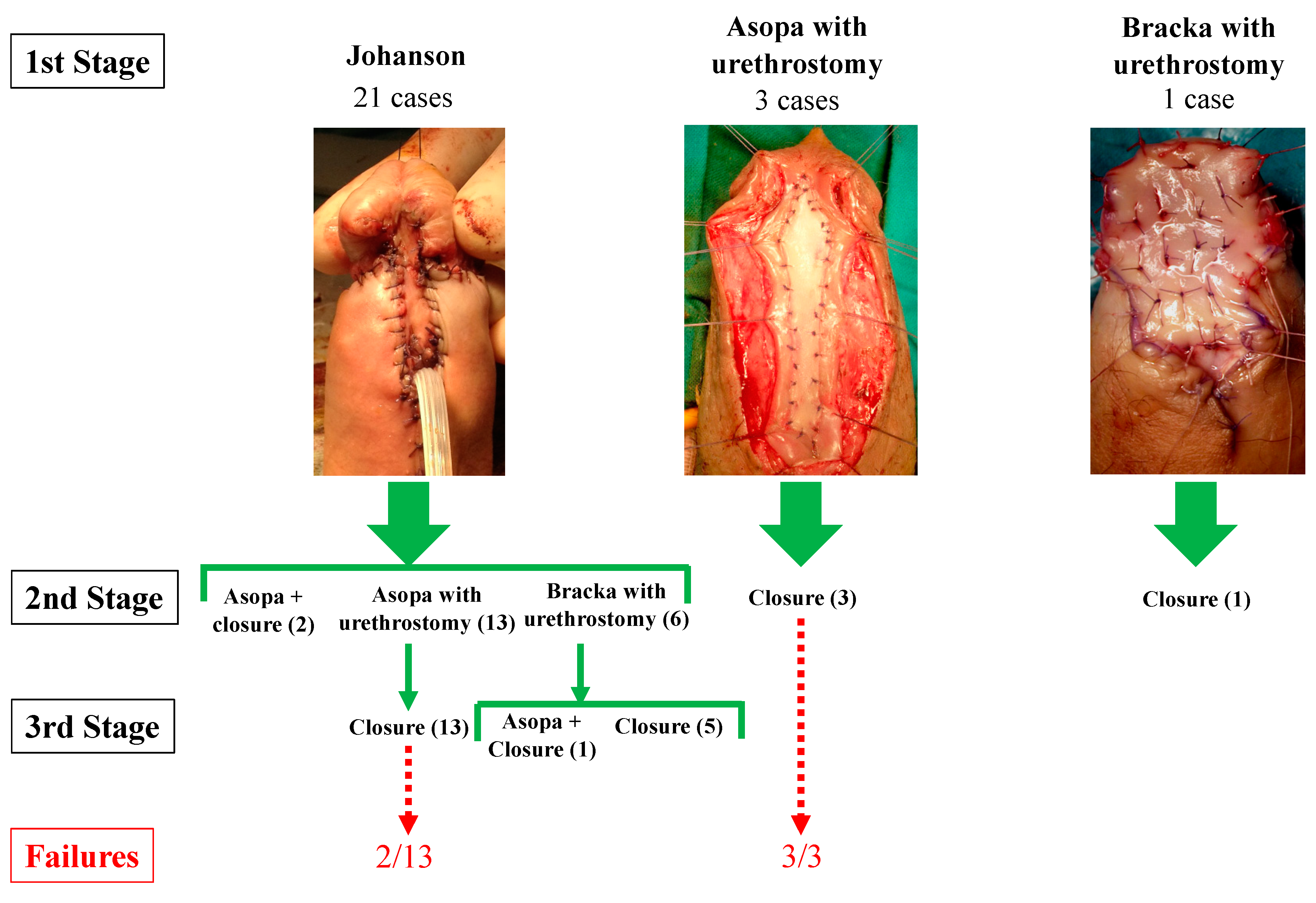

2.3. Type of Surgery and Technical Considerations

- (a)

- A simple opening of the strictured urethra and leaving a penile urethrostomy, as described by Johanson [9];

- (b)

- An opening of the strictured urethra with concomitant dorsal augmentation of the urethral plate with a BMG, as described by Asopa, additionally leaving a penile urethrostomy [10];

- (c)

- An opening of the strictured urethra, complete removal of the diseased urethral plate, reconstruction of an entire new urethral plate with a BMG, as described by Bracka, additionally leaving a penile urethrostomy [11].

2.4. Postoperative Management

2.4.1. First Stage and Second Stage without Re-Tubularization

2.4.2. Re-Tubularization Stage

2.5. Statistical Considerations

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Powell, J.J.; Wojnamwska, F. Lichen sclerosus. Lancet 1999, 353, 1777–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lumen, N.; Hoebeke, P.; Willemsen, P.; De Troyer, B.; Pieters, R.; Oosterlinck, W. Etiology of urethral stricture disease in the 21st century. J. Urol. 2009, 182, 983–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palminteri, E.; Berdondini, E.; Verze, P.; De Nunzio, C.; Vitarelli, A.; Carmignani, L. Contemporary urethral stricture characteristics in the developed world. Urology 2013, 81, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venn; Mundy Urethroplasty for balanitis xerotica obliterans. Br. J. Urol. 1998, 81, 735–737. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, L.; McCammon, K.; Metro, M.; Virasoro, R. SIU/ICUD Consultation on urethral strictures: Anterior urethra—Lichen sclerosus. Urology 2014, 83, S27–S30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, A.C.; Palminteri, E.; Lazzeri, M.; Guanzoni, G.; Barbagli, G.; Webster, G.D. Heroic measures may not always be justified in extensive urethral stricture due to lichen sclerosus (balanitis xerotica obliterans). Urology 2004, 64, 565–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, S.; Barbagli, G.; Kirpekar, D.; Mirri, F.; Lazzeri, M. Lichen Sclerosus of the Male Genitalia and Urethra: Surgical Options and Results in a Multicenter International Experience with 215 Patients. Eur. Urol. 2009, 55, 945–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubey, D.; Sehgal, A.; Srivastava, A.; Mandhani, A.; Kapoor, R.; Kumar, A. Buccal mucosal urethroplasty for balanitis xerotica obliterans related urethral strictures: The outcome of 1 and 2-stage techniques. J. Urol. 2005, 173, 463–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johanson, B. The reconstruction in stenosis of the male urethra. Z Urol. 1953, 46, 361–375. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/13103629/ (accessed on 23 May 2022). [PubMed]

- Asopa, H.S.; Garg, M.; Singhal, G.G.; Singh, L.; Asopa, J.; Nischal, A. Dorsal free graft urethroplasty for urethral stricture by ventral sagittal urethrotomy approach. Urology 2001, 58, 657–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bracka, A. A versatile two-stage hypospadias repair. Br. J. Plast. Surg. 1995, 48, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozinn, S.I.; Harty, N.J.; Zinman, L.; Buckley, J.C. Management of complex anterior urethral strictures with multistage buccal mucosa graft reconstruction. Urology 2013, 82, 718–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwell, T.J.; Venn, S.N.; Mundy, A.R. Changing practice in anterior urethroplasty. Br. J. Urol. 1999, 83, 631–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrich, D.E.; Mundy, A.R. What is the Best Technique for Urethroplasty? Eur. Urol. 2008, 54, 1031–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbagli, G.; Balò, S.; Sansalone, S.; Lazzeri, M. One-stage and two-stage penile buccal mucosa urethroplasty. Afr. J. Urol. 2016, 22, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Esperto, F.; Verla, W.; Ploumidis, A.; Barratt, R.; La Rocca, R.; Lumen, N.; Yuan, Y.; Campos-Juanatey, F.; Greenwell, T.; Martins, F.; et al. What is the role of single-stage oral mucosa graft urethroplasty in the surgical management of lichen sclerosus-related stricture disease in men? A systematic review. World J. Urol. 2022, 40, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angulo, J.; Arance, I.; Esquinas, C.; Nikolavsky, D.; Martins, N.; Martins, F. Treatment of long anterior urethral stricture associated to lichen sclerosus. Actas Urol. Esp. 2017, 41, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrich, D.E.; Greenwell, T.J.; Mundy, A.R. The problems of penile urethroplasty with particular reference to 2-stage reconstructions. J. Urol. 2003, 170, 87–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, D.P.; Elliott, S.P.; Voelzke, B.B.; Erickson, B.; McClung, C.D.; Presson, A.P.; Zhang, C.; Myers, J.B. Patient Reported Sexual Function After Staged Penile Urethroplasty. Urology 2015, 86, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total | 2St-BMGU | 3St-BMGU | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 35 (100%) | n = 9 (25.7%) | n = 26 (74.3%) | |||

| Age (months), mean (SD) | 45.79 (12.80) | 42.47 (14.09) | 46.94 (12.40) | 0.37 * | |

| Previous urethral surgery, n (%) | No | 4 (11%) | 3 (33%) | 1 (4%) | 0.044 ° |

| Yes | 31 (89%) | 6 (67%) | 25 (96%) | ||

| Previous surgery for hypospadias, n (%) | No | 29 (83%) | 8 (89%) | 21 (81%) | 1 ° |

| Yes | 6 (17%) | 1 (11%) | 5 (19%) | ||

| Previous urethroplasty, n (%) | No | 30 (86%) | 9 (100%) | 21 (81%) | 0.30 ° |

| Yes | 5 (14%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (19%) | ||

| Previous meatoplasty, n (%) | No | 27 (77%) | 8 (89%) | 19 (73%) | 0.65 ° |

| Yes | 8 (23%) | 1 (11%) | 7 (27%) | ||

| Previous dilatations, n (%) | No | 15 (43%) | 4 (44%) | 11 (42%) | 1 ° |

| Yes | 20 (57%) | 5 (56%) | 15 (58%) | ||

| Previous urethrotomy, n (%) | No | 27 (77%) | 6 (67%) | 21 (81%) | 0.40 ° |

| Yes | 8 (23%) | 3 (33%) | 5 (19%) | ||

| Qmax before surgery (mL/s), median (IQR) | 6 (4.6–7) | 6 (4–6.5) | 5 (4.6–7) | 0.82 * | |

| First-stage surgery, n (%) | Johanson only | 28 (77%) | 3 (33%) | 25 (96.1%) | <0.001 ° |

| Other | 7 (23%) | 6 (67%) | 1 (3.9%) | ||

| Months between first and last stage, n (%) | <12 m | 8 (23%) | 6 (67%) | 2 (8%) | 0.001 ° |

| >12 m | 27 (77%) | 3 (33%) | 24 (92%) |

| Total | Treatment Failure | Treatment Success | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 25 (100%) | n = 5 (20%) | n = 20 (80%) | |||

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 46.02 (11.12) | 42.25 (19.02) | 46.96 (8.68) | 0.41 * | |

| Previous urethral surgery, n (%) | No | 4 (16%) | 2 (50%) | 2 (50%) | 0.17 ° |

| Yes | 21 (84%) | 3 (14.3%) | 18 (85.7%) | ||

| Previous surgery for hypospadias, n (%) | No | 23 (92%) | 4 (17.4%) | 19 (82.6%) | 0.37 ° |

| Yes | 2 (8%) | 1 (50%) | 1 (50%) | ||

| Previous urethroplasty, n (%) | No | 21 (84%) | 4 (19%) | 17 (81%) | 1 ° |

| Yes | 4 (16%) | 1 (25%) | 3 (75%) | ||

| Previous meatoplasty, n (%) | No | 19 (76%) | 4 (21.1%) | 15 (78.9%) | 1 ° |

| Yes | 6 (24%) | 1 (16.7%) | 5 (83.3%) | ||

| Previous dilatations, n (%) | No | 12 (48%) | 3 (25%) | 9 (75%) | 0.64 ° |

| Yes | 13 (52%) | 2 (15.4%) | 11 (84.6%) | ||

| Previous urethrotomy, n (%) | No | 20 (80%) | 4 (20%) | 16 (80%) | 1 ° |

| Yes | 5 (20%) | 1 (20%) | 4 (80%) | ||

| Qmax before surgery (mL/s), median (IQR) | 6 (4.8–8.5) | 6 (6–6) | 6 (4.6–10) | 0.88 * | |

| Number of stages, n (%) | 2St-BMGU | 6 (24%) | 3 (50%) | 3 (50%) | 0.07 ° |

| 3St-BMGU | 19 (76%) | 2 (10.5%) | 17 (89.5%) | ||

| First-stage surgery, n (%) | Johanson only | 21 (84%) | 2 (9.5%) | 19 (90.5%) | <0.001 |

| Other | 4 (16%) | 3 (75%) | 1 (25%) | ||

| Months between first and last stage, n (%) | <12 m | 6 (24%) | 4 (66.7%) | 2 (33.3%) | 0.005 ° |

| >12 m | 19 (76%) | 1 (5.3%) | 18 (94.7%) |

| Univariable model | Coef. | p-Value | 95% CI | |

| Treatment course (<12 m vs. >12 m) | 36 | 0.008 | 2.585 | 501.268 |

| Number of stages (2St-BMGU vs. 3St-BMGU) | 8.5 | 0.053 | 00.971 | 74.424 |

| Multivariable model | Coef. | p-value | 95% CI | |

| Treatment course (<12 m vs. >12 m) | 27 | 0.031 | 1.359 | 537.553 |

| Number of stages (2St-BMGU vs. 3St-BMGU) | 1.743 | 0.715 | 0.089 | 34.231 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Palminteri, E.; Gobbo, A.; Preto, M.; Alessio, P.; Vitelli, D.; Gatti, L.; Buffi, N.M. The Role of Multi-Staged Urethroplasty in Lichen Sclerosus Penile Urethral Strictures. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6961. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11236961

Palminteri E, Gobbo A, Preto M, Alessio P, Vitelli D, Gatti L, Buffi NM. The Role of Multi-Staged Urethroplasty in Lichen Sclerosus Penile Urethral Strictures. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2022; 11(23):6961. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11236961

Chicago/Turabian StylePalminteri, Enzo, Andrea Gobbo, Mirko Preto, Paolo Alessio, Daniele Vitelli, Lorenzo Gatti, and Nicolò Maria Buffi. 2022. "The Role of Multi-Staged Urethroplasty in Lichen Sclerosus Penile Urethral Strictures" Journal of Clinical Medicine 11, no. 23: 6961. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11236961

APA StylePalminteri, E., Gobbo, A., Preto, M., Alessio, P., Vitelli, D., Gatti, L., & Buffi, N. M. (2022). The Role of Multi-Staged Urethroplasty in Lichen Sclerosus Penile Urethral Strictures. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 11(23), 6961. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11236961