Neonatal Morbidity after Cervical Ripening with a Singleton Fetus in a Breech Presentation at Term

Abstract

1. Introduction

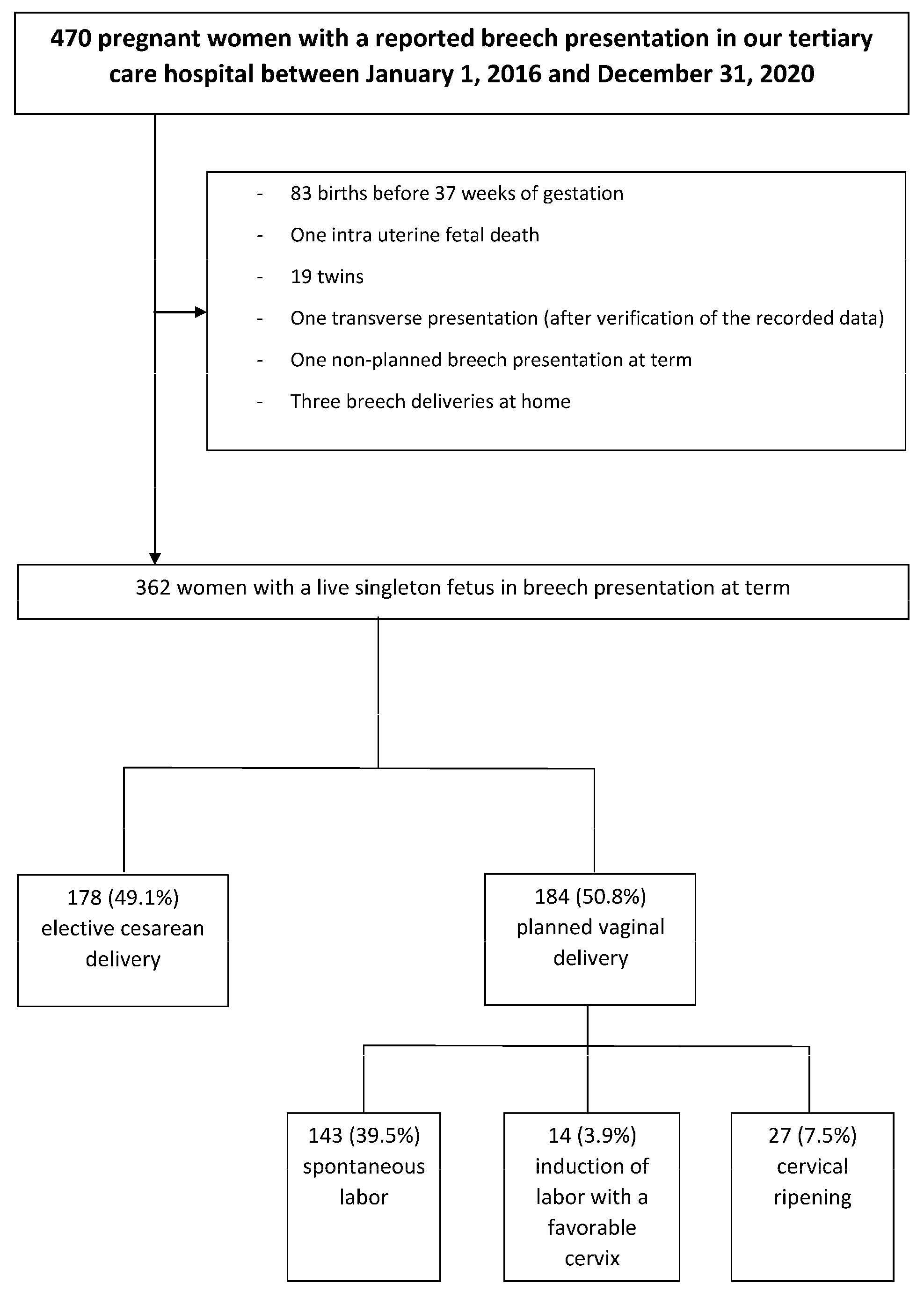

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Blondel, B.; Coulm, B.; Bonnet, C.; Goffinet, F.; Le Ray, C. National Coordination Group of the National Perinatal Surveys. Trends in perinatal health in metropolitan France from 1995 to 2016: Results from the French National Perinatal Surveys. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Hum. Reprod. 2017, 46, 701–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hannah, M.E.; Hannah, W.J.; Hewson, S.A.; Hodnett, E.D.; Saigal, S.; Willan, A.R.; Term Breech Trial Collaborative Group. Planned caesarean section versus planned vaginal birth for breech presentation at term: A randomised multicentre trial. Lancet 2000, 356, 1375–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goffinet, F.; Carayol, M.; Foidart, J.M.; Alexander, S.; Uzan, S.; Subtil, D.; Bréart, G.; PREMODA Study Group. Is planned vaginal delivery for breech presentation at term still an option? Results of an observational prospective survey in France and Belgium. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006, 194, 1002–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanc-Petitjean, P.; Salomé, M.; Dupont, C.; Crenn-Hebert, C.; Gaudineau, A.; Perrotte, F.; Raynal, P.; Clouqueur, E.; Beucher, G.; Carbonne, B.; et al. Labour induction practices in France: A population-based declarative survey in 94 maternity units. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Hum. Reprod. 2018, 47, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parant, O.; Bayoumeu, F. Breech Presentation: CNGOF Guidelines for Clinical Practice Labour and Induction. Gynecol. Obstet. Fertil. Senol. 2020, 48, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Burgos, J.; Arana, I.; Garitano, I.; Rodríguez, L.; Cobos, P.; Osuna, C.; del Mar Centeno, M.; Fernández-Llebrez, L. Induction of labor in breech presentation at term: A retrospective cohort study. J. Perinat. Med. 2017, 45, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sentilhes, L.; Schmitz, T.; Azria, E.; Gallot, D.; Ducarme, G.; Korb, D.; Mattuizzi, A.; Parant, O.; Sananès, N.; Baumann, S.; et al. Breech presentation: Clinical practice guidelines from the French College of Gynaecologists and Obstetricians (CNGOF). Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2020, 252, 599–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Hypertension in pregnancy. Report of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013, 22, 1122–1131. [Google Scholar]

- Ego, A. Definitions: Small for gestational age and intrauterine growth retardation. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Biol. Reprod. 2013, 42, 872–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Association of Diabetes Pregnancy Study Groups. Recommendations on the diagnosis and classification of hyperglycaemia in pregnancy. Diabetes Care 2010, 33, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bleu, G.; Demetz, J.; Michel, S.; Drain, A.; Houfflin-Debarge, V.; Deruelle, P.; Subtil, D. Effectiveness and safety of induction of labor. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Hum. Reprod. 2017, 46, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaillard, T.; Girault, A.; Alexander, S.; Goffinet, F.; Le Ray, C. Is induction of labor a reasonable option for breech presentation? Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2019, 98, 885–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breton, A.; Gueudry, P.; Branger, B.; Le Baccon, F.A.; Thubert, T.; Arthuis, C.; Winer, N.; Dochez, V. Comparison of obstetric prognosis of attempts of breech delivery: Spontaneous labor versus induced labor. Gynecol. Obstet. Fertil. Senol. 2018, 46, 632–638. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Macharey, G.; Ulander, V.M.; Heinonen, S.; Kostev, K.; Nuutila, M.; Väisänen-Tommiska, M. Induction of labor in breech presentations at term: A retrospective observational study. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2016, 293, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, W.; Liu, F.; Liu, S.; Gratton, S.M.; El-Chaar, D.; Wen, S.W.; Chen, D. Comparison of outcomes between induction of labor and spontaneous labor for term breech—A systemic review and meta analysis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2018, 222, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welle-Strand, J.A.H.; Tappert, C.; Eggebø, T.M. Induction of labor in breech presentations—A retrospective cohort study. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2021, 100, 1336–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khobzaoui, M.; Ghesquiere, L.; Drumez, E.; Debarge, V.; Subtil, D.; Garabedian, C. Cervical maturation in breech presentation: Mechanical versus prostaglandin methods. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Hum. Reprod. 2022, 51, 102404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nkobetchou, M.; Korb, D.; Giral, E.; Renevier, B.; Sibony, O. Cervical ripening for a singleton fetus in breech prensentation at term: Comparison between mechanical and pharmaceutical methods. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Hum. Reprod. 2022, 51, 102258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korb, D.; Schmitz, T.; Alexander, S.; Subtil, D.; Verspyck, E.; Deneux-Tharaux, C.; Goffinet, F. Association between planned mode of delivery and severe maternal morbidity in women with breech presentations: A secondary analysis of the PREMODA prospective general population study. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Hum. Reprod. 2020, 49, 101662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarniat, A.; Eluard, V.; Martz, O.; Calmelet, P.; Calmelet, A.; Dellinger, P.; Sagot, P. Induced labour at term and breech presentation: Experience of a level IIB French maternity. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Hum. Reprod. 2017, 46, 597–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Planned Cesarean Delivery, n = 178 (49.1%) | Spontaneous Labor, n = 143 (39.5%) | IOL with Favorable Cervix, n = 14 (3.9%) | Cervical Ripening, n = 27 (7.5%) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 30.5 ± 4.7 | 30.0 ± 4.2 | 29.4 ± 4.3 | 30.6 ± 3.9 | 0.80 |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI, kg/m2 | 23.9 ± 4.8 | 23.1 ± 5.1 | 24.2 ± 6.3 | 25.2 ± 5.3 | 0.07 |

| Obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) | 21 (11.8) | 16 (11.2) | 2 (14.2) | 4 (14.8) | 0.87 |

| Preexisting type 1 or 2 diabetes | 1 (0.6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.95 |

| Chronic hypertension | 3 (1.7) | 0 | 0 | 1 (3.7) | 0.20 |

| Nulliparity | 93 (52.2) | 75 (52.4) | 9 (64.3) | 15 (55.6) | 0.80 |

| Uterine malformation | 7 (3.9) | 8 (5.6) | 1 (7.1) | 2 (7.4) | 0.50 |

| One previous cesarean delivery | 40 (22.5) | 6 (4.2) | 0 | 1 (3.7) | <0.001 |

| ART | 15 (8.4) | 8 (5.6) | 1 (7.1) | 3 (11.1) | 0.34 |

| Gestational age at delivery, weeks | 39.0 ± 0.8 | 39.5 ± 1.1 | 40.0 ± 1.4 | 40.1 ± 1.6 | 0.17 |

| Elective cesarean delivery before labor | - | - | 0 | 4 (14.8) | 0.64 |

| Mode of delivery | |||||

| Spontaneous vaginal delivery | - | 124 (86.7) | 13 (92.9) | 17 (63.0) | 0.01 |

| Operative vaginal delivery | - | 3 (2.1) | 0 | 0 | 0.90 |

| Cesarean delivery during labor | - | 16 (11.2) | 1 (7.1) | 6 (22.2) | 0.16 |

| Indication for cesarean delivery during labor | |||||

| Non-reassuring FHR only | - | 9 (56.3) | 0 | 5 (83.3) | 0.04 |

| Arrested progress only | - | 5 (31.2) | 1 (100) | 1 (16.7) | 0.02 |

| Non-reassuring FHR and arrested progress | - | 2 (12.5) | 0 | 0 | 0.72 |

| Postpartum hemorrhage | 26 (14.6) | 12 (8.4) | 1 (7.1) | 4 (14.8) | 0.30 |

| Severe PPH | 5 (2.8) | 3 (2.1) | 0 | 0 | 0.96 |

| Episiotomy | - | 31 (21.7) | 3 (21.4) | 4 (14.8) | 0.17 |

| Third- or fourth-degree perineal | - | 2 (1.4) | 0 | 0 | 0.72 |

| Perineal hematoma | - | 0 | 0 | 1 (3.7) | 0.11 |

| Need for additional uterotonic agent (sulprostone) | 1 (0.6) | 0 | 0 | 1 (3.7) | 0.26 |

| Second-line therapies | 2 (1.1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.54 |

| Chorioamnionitis | 0 | 2 (1.4) | 1 (7.1) | 0 | 0.05 |

| Infections | 4 (2.2) | 4 (2.8) | 0 | 0 | 0.51 |

| Blood transfusion | 2 (1.1) | 2 (1.4) | 0 | 0 | 0.92 |

| Thromboembolic event | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Intensive care unit admission | 2 (1.1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.63 |

| Maternal death | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Maternal morbidity | 14 (7.9) | 7 (4.9) | 0 | 2 (7.4) | 0.70 |

| IOL with Favorable Cervix, n = 14 (4.0%) | Cervical Ripening, n = 27 (7.5%) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational age at IOL, weeks | 40.0 ± 1.4 | 40.1 ± 1.6 | 0.63 |

| Indication for IOL | |||

| Prolonged pregnancy | 4 (28.7) | 11 (40.8) | 0.47 |

| Diabetes | 0 | 3 (11.1) | 0.87 |

| SGA | 1 (7.1) | 4 (14.8) | 0.54 |

| Pregnancy-associated hypertensive disorders | 0 | 1 (3.7) | 0.52 |

| Prelabor rupture of membranes | 7 (50.0) | 1 (3.7) | 0.001 |

| Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy | 0 | 1 (3.7) | 0.52 |

| Abnormality of fetal vitality | 1 (7.1) | 4 (14.8) | 0.54 |

| Other medical indication | 1 (7.1) | 2 (7.4) | 0.99 |

| Bishop score before IOL | 6.9 ± 1.4 | 3.4 ± 0.4 | <0.0001 |

| Methods of cervical ripening | |||

| CRB alone | - | 20 (74.1) | - |

| Dinoprostone vaginal insert alone | - | 3 (11.1) | - |

| Repeated dinoprostone vaginal insert | - | 4 (14.8) | - |

| Time-interval from IOL beginning to delivery, hours | 9.0 ± 3.0 | 24.0 ± 14.0 | <0.0001 |

| Planned Cesarean Delivery, n = 178 (49.2%) | Spontaneous Labor, n = 143 (39.5%) | IOL with Favorable Cervix, n = 14 (4.0%) | Cervical Ripening, n = 27 (7.5%) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 81 (45.6) | 61 (42.7) | 4 (28.6) | 8 (29.6) | 0.30 |

| Birth weight, g | 3215 ± 505 | 3098 ± 365 | 3176 ± 399 | 3129 ± 511 | 0.06 |

| 5 min Apgar score less than 7 | 0 | 2 (1.4) | 1 (7.1) | 1 (3.7) | 0.02 |

| pH less than 7.00 | 0 | 4 (2.8) | 0 | 2 (7.4) | 0.02 |

| Need for resuscitation or intubation | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.7) | 0 | 1 (3.7) | 0.41 |

| NICU admission longer than 24 h | 2 (1.2) | 2 (1.4) | 2 (14.2) | 1 (3.7) | 0.03 |

| Respiratory distress syndrome | 2 (1.2) | 2 (1.4) | 0 | 2 (7.4) | 0.20 |

| Neonatal hyperbilirubinemia | 1 (0.6) | 0 | 1 (7.1) | 0 | 0.08 |

| Sepsis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Seizures | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (3.7) | 0.11 |

| Intraventricular hemorrhage greater than grade 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Neonatal trauma | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Neonatal death | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (3.7) | 0.11 |

| Severe neonatal morbidity | 2 (1.2) | 5 (3.5) | 2 (14.2) | 2 (7.4) | 0.02 |

| Severe Maternal Morbidity * | Severe Neonatal Morbidity ** | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | No (n = 339) | Yes (n = 23) | p Value | No (n = 351) | Yes (n = 11) | p Value |

| Age, years | 30.3 ± 4.3 | 29.7 ± 6.3 | 0.40 | 30.3 ± 4.5 | 28.3 ± 2.6 | 0.06 |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI, kg/m2 | 23.7 ± 5.1 | 23.6 ± 3.2 | 0.40 | 23.8 ± 5.0 | 20.9 ± 3.3 | 0.04 |

| Obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) | 43 (12.7) | 0 | 0.09 | 43 (12.2) | 0 | 0.42 |

| Nulliparity | 176 (51.9) | 16 (69.6) | 0.10 | 184 (52.4) | 8 (72.7) | 0.23 |

| Gestational age at delivery, weeks | 39.3 ± 1.1 | 39.2 ± 1.1 | 0.44 | 39.3 ± 1.1 | 39.9 ± 1.3 | 0.22 |

| Mode of labor | 0.77 | 0.02 | ||||

| Elective cesarean delivery | 164 (48.4) | 14 (60.9) | 176 (50.1) | 2 (18.2) | ||

| Spontaneous labor | 136 (40.1) | 7 (30.4) | 138 (39.3) | 5 (45.4) | ||

| IOL with favorable cervix | 14 (4.1) | 0 | 12 (3.4) | 2 (18.2) | ||

| Cervical ripening | 25 (7.4) | 2 (8.7) | 25 (7.2) | 2 (18.2) | ||

| Method of cervical ripening | 0.52 | 0.52 | ||||

| Cervical ripening balloon | 19 (76.0) | 1 (50.0) | 19 (76.0) | 1 (50.0) | ||

| Dinoprostone vaginal insert | 5 (20.0) | 1 (50.0) | 5 (20.0) | 1 (50.0) | ||

| Repeated dinoprostone insert | 1 (4.0) | 0 | 1 (4.0) | 0 | ||

| Cesarean delivery | 190 (56.0) | 15 (65.2) | 0.40 | 202 (57.6) | 3 (27.3) | 0.06 |

| Birth weight, g | 3158 ± 445 | 3195 ± 572 | 0.81 | 3159 ± 453 | 3215 ± 466 | 0.72 |

| Severe Maternal Morbidity (n = 23) | Severe Neonatal Morbidity (n = 11) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable * | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p Value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p Value |

| Age (/year) | 1.00 (0.90–1.10) | 0.93 | 0.93 (0.79–1.09) | 0.41 |

| Nulliparity | 2.01 (0.72–6.57) | 0.21 | 1.25 (0.29–6.57) | 0.84 |

| Multiparity | Reference | - | Reference | - |

| Gestational age at delivery, weeks | ||||

| Less than 39 weeks | 1.16 (0.46–2.84) | 0.77 | 1.28 (0.24–6.08) | 0.81 |

| 39 to less than 41 | Reference | - | Reference | - |

| Greater than 41 | 0.26 (0.01–1.67) | 0.22 | 2.76 (0.51–14.2) | 0.24 |

| Mode of labor | ||||

| Elective cesarean delivery | Reference | - | Reference | - |

| Spontaneous labor | 0.52 (0.03–3.45) | 0.61 | 1.36 (0.05–19.2) | 0.84 |

| IOL with favorable cervix | 0 | - | 4.60 (0.11–106) | 0.42 |

| Cervical ripening | 1.29 (0.05–11.5) | 0.81 | 2.80 (0.10–43.6) | 0.53 |

| Mode of delivery | ||||

| Vaginal delivery | Reference | - | Reference | - |

| Cesarean delivery during labor | 0.82 (0.04–5.45) | 0.94 | 0.54 (0.02–4.13) | 0.62 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Berthommier, L.; Planche, L.; Ducarme, G. Neonatal Morbidity after Cervical Ripening with a Singleton Fetus in a Breech Presentation at Term. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 7118. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11237118

Berthommier L, Planche L, Ducarme G. Neonatal Morbidity after Cervical Ripening with a Singleton Fetus in a Breech Presentation at Term. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2022; 11(23):7118. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11237118

Chicago/Turabian StyleBerthommier, Laura, Lucie Planche, and Guillaume Ducarme. 2022. "Neonatal Morbidity after Cervical Ripening with a Singleton Fetus in a Breech Presentation at Term" Journal of Clinical Medicine 11, no. 23: 7118. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11237118

APA StyleBerthommier, L., Planche, L., & Ducarme, G. (2022). Neonatal Morbidity after Cervical Ripening with a Singleton Fetus in a Breech Presentation at Term. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 11(23), 7118. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11237118