Parenting Stress in Mothers of Children and Adolescents with Down Syndrome

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Maternal Stress

2.3.2. Cognitive Measures

2.3.3. Adaptive Abilities

2.3.4. Emotional and Behavioral Problems and Social Communication Abilities

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

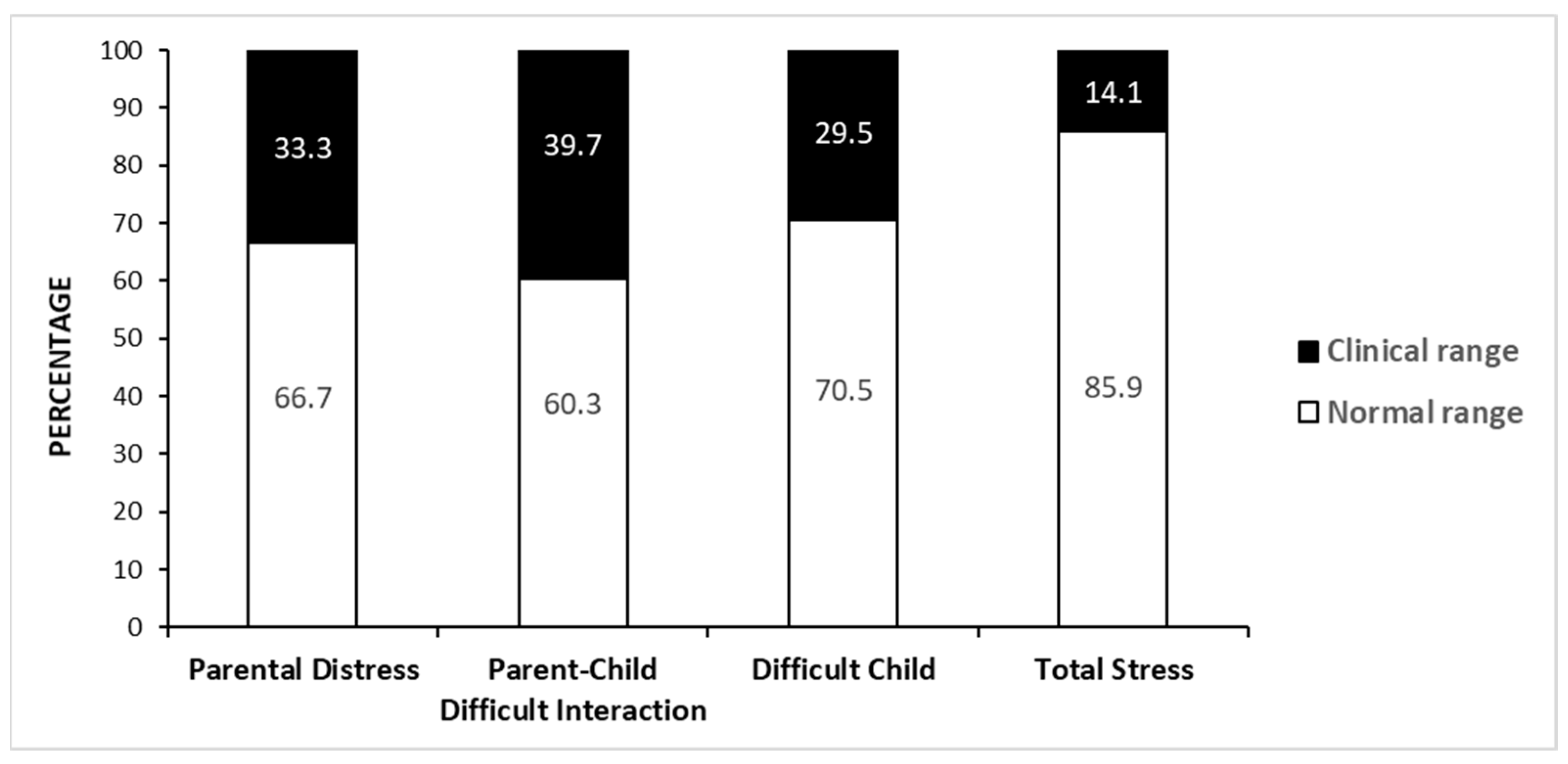

3.1. Maternal Stress

3.2. Association between Maternal Stress and Child Features

3.3. Association between Maternal Stress and Child Emotional and Behavior Problems

3.4. Association between Maternal Stress and Socio-Demographic Factors

3.5. Differences in PSI Scores between Employed and Unemployed Mothers

3.6. Differences in PSI Scores between Mothers with High and Low SES

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abidin, R.R. The Determinants of Parenting Behavior. J. Clin. Child Psychol. 1992, 21, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidin, R.R. Parenting Stress Index, 3rd ed.; Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.: Odessa, FL, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Arim, R.G.; Garner, R.E.; Brehaut, J.C.; Lach, L.M.; MacKenzie, M.J.; Rosenbaum, P.L.; Kohen, D.E. Contextual influences of parenting behaviors for children with neurodevelopmental disorders: Results from a Canadian national survey. Disabil. Rehabil. 2012, 34, 2222–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamarat, E.; Thompson, D.; Zabrucky, K.M.; Steele, D.; Matheny, K.B.; Aysan, F. Perceived Stress and Coping Resource Availability as Predictors of Life Satisfaction in Young, Middle-Aged, and Older Adults. Exp. Aging Res. 2001, 27, 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, J.S.R.; Staten, R.T.; Hall, L.A.; Lennie, T.A. The Relationship among Young Adult College Students’ Depression, Anxiety, Stress, Demographics, Life Satisfaction, and Coping Styles. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2012, 33, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulz, R.; Sherwood, P.R. Physical and Mental Health Effects of Family Caregiving. AJN Am. J. Nurs. 2008, 108, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daundasekara, S.S.; Schuler, B.R.; Beauchamp, J.E.; Hernandez, D.C. The mediating effect of parenting stress and couple relationship quality on the association between material hardship trajectories and maternal mental health status. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 290, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabrera, N.J.; Fagan, J.; Wight, V.; Schadler, C. Influence of Mother, Father, and Child Risk on Parenting and Children’s Cognitive and Social Behaviors. Child Dev. 2011, 82, 1985–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deater-Deckard, K. Parenting stress and children’s development: Introduction to the special issue. Infant Child Dev. 2005, 14, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerstein, E.D.; Crnic, K.A.; Blacher, J.; Baker, B.L. Resilience and the course of daily parenting stress in families of young children with intellectual disabilities. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2009, 53, 981–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Rubilar, J.; Arán-Filippetti, V. The importance of parenthood for the child’s cognitive development: A theoretical revision. Rev. Latinoam. Cienc. Soc. Niñez Juvent. 2014, 12, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.A.; Papadopoulos, N.; Chellew, T.; Rinehart, N.J.; Sciberras, E. Associations between parenting stress, parent mental health and child sleep problems for children with ADHD and ASD: Systematic review. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2019, 93, 103463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holden, E.; Banez, G.A. Child abuse potential and parenting stress within maltreating families. J. Fam. Violence 1996, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mash, E.J.; Johnston, C. Determinants of Parenting Stress: Illustrations from Families of Hyperactive Children and Families of Physically Abused Children. J. Clin. Child Psychol. 1990, 19, 313–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miragoli, S.; Balzarotti, S.; Camisasca, E.; Di Blasio, P. Parents’ perception of child behavior, parenting stress, and child abuse potential: Individual and partner influences. Child Abus. Negl. 2018, 84, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitz, K.; Ketterlinus, R.D.; Brandt, L.J. The Role of Stress, Social Support, and Family Environment in Adolescent Mothers’ Parenting. J. Adolesc. Res. 1995, 10, 358–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, C.; Green, A.J. Parenting stress and anger expression as predictors of child abuse potential. Child Abus. Negl. 1997, 21, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whipple, E.E.; Webster-Stratton, C. The role of parental stress in physically abusive families. Child Abus. Negl. 1991, 15, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyl, D.D.; Roggman, L.A.; Newland, L.A. Stress, maternal depression, and negative mother-infant interactions in relation to infant attachment. Infant Ment. Health J. 2002, 23, 145–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouch, E.; Radcliff, E.; Brown, M.J.; Hung, P. Exploring the association between parenting stress and a child’s exposure to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2019, 102, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagner, D.M.; Sheinkopf, S.J.; Miller-Loncar, C.; LaGasse, L.L.; Lester, B.M.; Liu, J.; Bauer, C.R.; Shankaran, S.; Bada, H.; Das, A. The Effect of Parenting Stress on Child Behavior Problems in High-Risk Children with Prenatal Drug Exposure. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2008, 40, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Buodo, G.; Moscardino, U.; Scrimin, S.; Altoè, G.; Palomba, D. Parenting Stress and Externalizing Behavior Symptoms in Children: The Impact of Emotional Reactivity. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2013, 44, 786–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, B.L.; Blacher, J.; Crnic, K.A.; Edelbrock, C. Behavior Problems and Parenting Stress in Families of Three-Year-Old Children with and Without Developmental Delays. Am. J. Ment. Retard. 2002, 107, 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, F.; Operto, F.F.; De Giacomo, A.; Margari, L.; Frolli, A.; Conson, M.; Ivagnes, S.; Monaco, M.; Margari, F. Parenting stress among parents of children with Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2016, 242, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuller, G.B.; Rankin, R.E. Differences in Levels of Parental Stress among Mothers of Learning Disabled, Emotionally Impaired, and Regular School Children. Percept. Mot. Ski. 1994, 78, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricci, L.A.; Hodapp, R.M. Fathers of children with Down’s syndrome versus other types of intellectual disability: Perceptions, stress and involvement. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2003, 47, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roach, M.A.; Orsmond, G.I.; Barratt, M.S. Mothers and Fathers of Children with Down Syndrome: Parental Stress and Involvement in Childcare. Am. J. Mental. Retard. 1999, 104, 422–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigue, J.R.; Morgan, S.B.; Geffken, G. Families of Autistic Children: Psychological Functioning of Mothers. J. Clin. Child Psychol. 1990, 19, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algorta, G.P.; Kragh, C.A.; Arnold, L.E.; Molina, B.S.G.; Hinshaw, S.P.; Swanson, J.M.; Hechtman, L.; Copley, L.M.; Lowe, M.; Jensen, P.S. Maternal ADHD Symptoms, Personality, and Parenting Stress: Differences Between Mothers of Children With ADHD and Mothers of Comparison Children. J. Atten. Disord. 2018, 22, 1266–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.; Su, J.; Jiang, Y.; Qin, S.; Chi, P.; Lin, X. Parenting Stress and Depressive Symptoms among Chinese Parents of Children with and without Oppositional Defiant Disorder: A Three-Wave Longitudinal Study. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2020, 51, 855–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carotenuto, M.; Messina, A.; Monda, V.; Precenzano, F.; Iacono, D.; Verrotti, A.; Piccorossi, A.; Gallai, B.; Roccella, M.; Parisi, L.; et al. Maternal Stress and Coping Strategies in Developmental Dyslexia: An Italian Multicenter Study. Front. Psychiatry 2017, 8, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashworth, M.; Palikara, O.; Van Herwegen, J. Comparing parental stress of children with neurodevelopmental disorders: The case of Williams syndrome, Down syndrome and autism spectrum disorders. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2019, 32, 1047–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Clercq, L.E.; Prinzie, P.; Warreyn, P.; Soenens, B.; Dieleman, L.M.; De Pauw, S.S.W. Expressed Emotion in Families of Children with and without Autism Spectrum Disorder, Cerebral Palsy and Down Syndrome: Relations with Parenting Stress and Parenting Behaviors. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2021, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenhower, A.S.; Baker, B.L.; Blacher, J. Preschool children with intellectual disability: Syndrome specificity, behaviour problems, and maternal well-being. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2005, 49, 657–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Most, D.E.; Fidler, D.J.; Laforce-Booth, C.; Kelly, J. Stress trajectories in mothers of young children with Down syndrome. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2006, 50, 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.Y.; Neil, N.; Friesen, D.C. Support needs, coping, and stress among parents and caregivers of people with Down syndrome. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2021, 119, 104113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, M.; Hodapp, R.M. Relating Stress of Mothers of Children With Developmental Disabilities to Family–School Partnerships. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2014, 52, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabrowska, A.; Pisula, E. Parenting stress and coping styles in mothers and fathers of pre-school children with autism and Down syndrome. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2010, 54, 266–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, F.; Hayiou-Thomas, M.E.; Arshad, Z.; Leonard, M.; Williams, F.J.; Katseniou, N.; Malouta, R.N.; Marshall, C.R.P.; Diamantopoulou, M.; Tang, E.; et al. Mind-Mindedness and Stress in Parents of Children with Developmental Disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2021, 51, 600–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumas, J.E.; Wolf, L.C.; Fisman, S.N.; Culligan, A. Parenting stress, child behavior problems, and dysphoria in parents of children with autism, down syndrome, behavior disorders, and normal development. Exceptionality 1991, 2, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, G.M.; Hastings, R.; Nash, S.; Hill, C. Using Matched Groups to Explore Child Behavior Problems and Maternal Well-Being in Children with Down Syndrome and Autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2009, 40, 610–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanfranchi, S.; Vianello, R. Stress, Locus of Control, and Family Cohesion and Adaptability in Parents of Children with Down, Williams, Fragile X, and Prader-Willi Syndromes. Am. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2012, 117, 207–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stores, R.; Stores, G.; Fellows, B.; Buckley, S. Daytime behaviour problems and maternal stress in children with Down’s syndrome, their siblings, and non-intellectually disabled and other intellectually disabled peers. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2002, 42, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodapp, R.M.; Ly, T.M.; Fidler, D.J.; Ricci, L.A. Less Stress, More Rewarding: Parenting Children With Down Syndrome. Parenting 2001, 1, 317–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walz, N.C.; Benson, B.A. Behavioral Phenotypes in Children with Down Syndrome, Prader-Willi Syndrome, or Angelman Syndrome. J. Dev. Phys. Disabil. 2002, 14, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wishart, J.G.; Johnston, F.H. The effects of experience on attribution of a stereotyped personality to children with Down’s syndrome. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2008, 34, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, D.B.; Hauser-Cram, P.; Crossman, M.K. Relationship dimensions of the ‘Down syndrome advantage’. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2015, 59, 506–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaeliou, C.; Polemikos, N.; Fryssira, E.; Kodakos, A.; Kaila, M.; Yiota, X.; Benaveli, E.; Michaelides, C.; Stroggilos, V.; Vrettopoulou, M. Behavioural profile and maternal stress in Greek young children with Williams syndrome. Child Care Health Dev. 2011, 38, 844–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norizan, A.; Shamsuddin, K. Predictors of parenting stress among Malaysian mothers of children with Down syndrome. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2010, 54, 992–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saloviita, T.; Italinna, M.; Leinonen, E. Explaining the parental stress of fathers and mothers caring for a child with intellectual disability: A Double ABCX Model. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2003, 47, 300–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloper, P.; Knussen, C.; Turner, S.; Cunningham, C. Factors Related to Stress and Satisfaction with Life in Families of Children with Down’s Syndrome. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 1991, 32, 655–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuzzocrea, F.; Murdaca, A.M.; Costa, S.; Filippello, P.; Larcan, R. Parental stress, coping strategies and social support in families of children with a disability. Child Care Pract. 2016, 22, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, B.A.; Conners, F.; Curtner-Smith, M.E. Parenting children with down syndrome: An analysis of parenting styles, parenting dimensions, and parental stress. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2017, 68, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doran, C.M.; Einfeld, S.L.; Madden, R.H.; Otim, M.; Horstead, S.K.; Ellis, L.A.; Emerson, E. How much does intellectual disability really cost? First estimates for Australia. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2012, 37, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breslau, N. Psychiatric Disorder in Children with Physical Disabilities. J. Am. Acad. Child Psychiatry 1985, 24, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salkever, D.S. Children’s Health Problems and Maternal Work Status. J. Hum. Resour. 1982, 17, 94–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, R.I.; Litchfield, L.C.; Warfield, M.E. Balancing Work and Family: Perspectives of Parents of Children with Developmental Disabilities. Fam. Soc. J. Contemp. Soc. Serv. 1995, 76, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heck, K.E.; Makuc, M.D. Parental employment and health insurance coverage among school-aged children with special health care needs. Am. J. Public Health 2000, 90, 1856–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhlthau, K.A.; Perrin, J.M. Child Health Status and Parental Employment. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2001, 155, 1346–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedov, G.; Annerén, G.; Wikblad, K. Swedish parents of children with Down’s syndrome. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2002, 16, 424–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, S.; Goodall, S.; Viney, R.; Einfeld, S. Societal cost of childhood intellectual disability in Australia. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2020, 64, 524–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiura, G.T. Demography of Family Households. Am. J. Ment. Retard. 1998, 103, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, H.; Petterson, B.; de Klerk, N.; Zubrick, S.; Glasson, E.; Sanders, R.; Bower, C. Association of sociodemographic characteristics of children with intellectual disability in Western Australia. Soc. Sci. Med. 2005, 60, 1499–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emerson, E.; Hatton, C.; Llewellyn, G.; Blacker, J.; Graham, H. Socio-economic position, household composition, health status and indicators of the well-being of mothers of children with and without intellectual disabilities. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2006, 50, 862–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonifacci, P.; Massi, L.; Pignataro, V.; Zocco, S.; Chiodo, S. Parenting Stress and Broader Phenotype in Parents of Children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, Dyslexia or Typical Development. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meppelder, M.; Hodes, M.; Kef, S.; Schuengel, C. Parenting stress and child behaviour problems among parents with intellectual disabilities: The buffering role of resources. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2014, 59, 664–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakula, D.M.; Wetter, S.E.; Peugh, J.L.; Modi, A.C. A Longitudinal Assessment of Parenting Stress in Parents of Children with New-Onset Epilepsy. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2021, 46, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-Y.; Chen, Y.-C.; Wang, H.-S.; Chen, D.-R. Parenting Stress and Related Factors in Parents of Children with Tourette Syndrome. J. Nurs. Res. 2007, 15, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almogbel, Y.S.; Goyal, R.; Sansgiry, S.S. Association between Parenting Stress and Functional Impairment among Children Diagnosed with Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Community Ment. Health J. 2017, 53, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azad, G.; Blacher, J.; Marcoulides, G.A. Mothers of children with developmental disabilities: Stress in early and middle childhood. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2013, 34, 3449–3459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisa, R.; Pola, R.; Franz, P.; Jessica, M. Developmental language disorder: Maternal stress level and behavioural difficulties of children with expressive and mixed receptive-expressive DLD. J. Commun. Disord. 2019, 80, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoneman, Z. Examining the Down syndrome advantage: Mothers and fathers of young children with disabilities. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2007, 51, 1006–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufman, J.; Birmaher, B.; Brent, D.; Rao, U.; Flynn, C.; Moreci, P.; Williamson, D.; Ryan, N. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): Initial Reliability and Validity Data. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1997, 36, 980–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abidin, R.R. Parenting Stress Index—Manual, 3rd ed.; Pediatric Psychology Press: Charlottesville, VA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Guarino, A.; Di Blasio, P.; D’Alessio, M.; Camisasca, E.; Serantoni, G. Parenting Stress Index—Forma Breve; Giunti Organizzazioni Speciali: Firenze, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Roid, G.H.; Miller, L.J.; Pomplun, M.; Koch, C. Leiter International Performance Scale, 3rd ed.; Western Psychological Services: Torrance, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Green, E.; Stroud, L.; Bloomfield, S.; Cronje, J.; Foxcroft, C.; Hurter, K. Griffith III: Griffiths Scales of Child Development, 3rd ed.; Association for Research in Infant and Child Development (ARCID): Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, P.L.; Oakland, T. Adaptive Behavior Assessment System®, 2nd ed.; Psychological Corporation: San Antonio, TX, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach, T.M.; Rescorla, L. Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles: An Integrated System of Multi-Informant Assessment; ASEBA: Burlington, VT, USA, 2001; ISBN 978-0-938565-73-4. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter, M.; Bailey, A.; Lord, C. Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ); Western Psychological Services: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cahill, B.M.; Glidden, L.M. Influence of child diagnosis on family and parental functioning: Down syndrome versus other disabilities. Am. J. Ment. Retard. 1996, 101, 149–160. [Google Scholar]

- Corrice, A.M.; Glidden, L.M. The Down Syndrome Advantage: Fact or Fiction? Am. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2009, 114, 254–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jess, M.; Flynn, S.; Bailey, T.; Hastings, R.P.; Totsika, V. Failure to replicate a robust Down syndrome advantage for maternal well-being. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2021, 65, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, H.R.; Graff, J.C. The Relationships among Adaptive Behaviors of Children with Autism, Family Support, Parenting Stress, and Coping. Issues Compr. Pediatr. Nurs. 2011, 34, 4–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theule, J.; Wiener, J.; Tannock, R.; Jenkins, J.M. Parenting Stress in Families of Children with ADHD: A Meta-Analysis. J. Emot. Behav. Disord. 2010, 21, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jijon, A.M.; Leonard, H.C. Parenting stress in parents of children with developmental coordination disorder. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2020, 104, 103695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, M.J. Down Syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 2344–2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovagnoli, G.; Postorino, V.; Fatta, L.M.; Sanges, V.; De Peppo, L.; Vassena, L.; De Rose, P.; Vicari, S.; Mazzone, L. Behavioral and emotional profile and parental stress in preschool children with autism spectrum disorder. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2015, 45–46, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barroso, N.E.; Mendez, L.; Graziano, P.A.; Bagner, D.M. Parenting Stress through the Lens of Different Clinical Groups: A Systematic Review & Meta-Analysis. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2018, 46, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, N.O.; Carter, A.S. Parenting Stress in Mothers and Fathers of Toddlers with Autism Spectrum Disorders: Associations with Child Characteristics. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2008, 38, 1278–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, S.; Sciberras, E.; Mulraney, M. The Relationship between Maternal Stress and Boys’ ADHD Symptoms and Quality of Life: An Australian Prospective Cohort Study. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2019, 50, e33–e38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadhwani, A.; Willen, J.M.; Lavallee, N.; Stepanians, M.; Miller, H.; Peters, S.U.; Barbieri-Welge, R.L.; Horowitz, L.T.; Noll, L.M.; Hundley, R.J.; et al. Maladaptive behaviors in individuals with Angelman syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2019, 179, 983–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidler, D.J.; Hodapp, R.M.; Dykens, E.M. Stress in Families of Young Children with Down Syndrome, Williams Syndrome, and Smith-Magenis Syndrome. Early Educ. Dev. 2000, 11, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicari, S.; Pontillo, M.; Armando, M. Neurodevelopmental and psychiatric issues in Down’s syndrome: Assessment and intervention. Psychiatr. Genet. 2013, 23, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dykens, E.M. Psychiatric and behavioral disorders in persons with Down syndrome. Ment. Retard. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 2007, 13, 272–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staunton, E.; Kehoe, C.; Sharkey, L. Families under pressure: Stress and quality of life in parents of children with an intellectual disability. Ir. J. Psychol. Med. 2020, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buescher, A.V.S.; Cidav, Z.; Knapp, M.; Mandell, D.S. Costs of Autism Spectrum Disorders in the United Kingdom and the United States. JAMA Pediatr. 2014, 168, 721–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnanasekaran, S.; Choueiri, R.; Neumeyer, A.; Ajari, O.; Shui, A.; Kuhlthau, K. Impact of employee benefits on families with children with autism spectrum disorders. Autism 2015, 20, 616–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, X.; Li, Y. Economic burdens on parents of children with autism: A literature review. CNS Spectr. 2020, 25, 468–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saunders, B.S.; Tilford, J.M.; Fussell, J.J.; Schulz, E.G.; Casey, P.H.; Kuo, D.Z. Financial and employment impact of intellectual disability on families of children with autism. Fam. Syst. Health 2015, 33, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoong, A.; Koritsas, S. The impact of caring for adults with intellectual disability on the quality of life of parents. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2012, 56, 609–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam El-Deen, N.; Alwakeel, A.A.; El-Gilany, A.-H.; Wahba, Y. Burden of family caregivers of Down syndrome children: A cross-sectional study. Fam. Pract. 2021, 38, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, D.L.; Drapela, L.A. Mostly the mother: Concentration of adverse employment effects on mothers of children with autism. Soc. Sci. J. 2010, 47, 578–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukemeyer, A.; Meyers, M.K.; Smeeding, T. Expensive Children in Poor Families: Out-of-Pocket Expenditures for the Care of Disabled and Chronically Ill Children in Welfare Families. J. Marriage Fam. 2000, 62, 399–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, R.J.; Stransky, M.L.; Cooley, W.C.; Moeschler, J.B. National Profile of Children with Down Syndrome: Disease Burden, Access to Care, and Family Impact. J. Pediatr. 2011, 159, 535–540.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, M.B.; Hwang, C.P. Well-being, involvement in paid work and division of child-care in parents of children with intellectual disabilities in Sweden. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2006, 50, 963–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dew, M.A.; Penkower, L.; Bromet, E.J. Effects of Unemployment on Mental Health in the Contemporary Family. Behav. Modif. 1991, 15, 501–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, G.W.; Levy, M.L.; Caplan, R.D. Job Loss and Depressive Symptoms in Couples: Common Stressors, Stress Transmission, or Relationship Disruption? J. Fam. Psychol. 2004, 18, 639–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, K.; Moser, K. Unemployment impairs mental health: Meta-analyses. J. Vocat. Behav. 2009, 74, 264–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomaguchi, K.; Johnson, W. Parenting Stress among Low-Income and Working-Class Fathers: The Role of Employment. J. Fam. Issues 2016, 37, 1535–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feeley, C.A.; Turner-Henson, A.; Christian, B.J.; Avis, K.T.; Heaton, K.; Lozano, D.; Su, X. Sleep Quality, Stress, Caregiver Burden, and Quality Of Life in Maternal Caregivers of Young Children With Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2014, 29, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaidman-Zait, A.; Most, T.; Tarrasch, R.; Haddad, E. Mothers’ and fathers’ involvement in intervention programs for deaf and hard of hearing children. Disabil. Rehabil. 2017, 40, 1301–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rankin, J.A.; Paisley, C.A.; Tomeny, T.S.; Eldred, S.W. Fathers of Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review of the Impact of Fathers’ Involvement on Youth, Families, and Intervention. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2019, 22, 458–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Channell, M.M. The Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS-2) in school-age children with Down syndrome at low risk for autism spectrum disorder. Autism Dev. Lang. Impair. 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Channell, M.M.; Phillips, B.A.; Loveall, S.J.; Conners, F.A.; Bussanich, P.M.; Klinger, L.G. Patterns of autism spectrum symptomatology in individuals with Down syndrome without comorbid autism spectrum disorder. J. Neurodev. Disord. 2015, 7, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parental Distress r (p) | Parent–Child Difficult Interaction r (p) | Difficult Child r (p) | Total Stress r (p) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internalizing problems (CBCL) | 0.281 * (0.013) | 0.363 ** (0.001) | 0.465 ** (<0.001) | 0.415 ** (<0.001) |

| Externalizing Problems (CBCL) | 0.313 * (0.005) | 0.394 ** (<0.001) | 0.623 ** (<0.001) | 0.550 ** (<0.001) |

| SCQ | 0.399 ** (<0.001) | 0.338 * (0.007) | 0.336 * (0.007) | 0.375 ** (0.002) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fucà, E.; Costanzo, F.; Ursumando, L.; Vicari, S. Parenting Stress in Mothers of Children and Adolescents with Down Syndrome. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 1188. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11051188

Fucà E, Costanzo F, Ursumando L, Vicari S. Parenting Stress in Mothers of Children and Adolescents with Down Syndrome. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2022; 11(5):1188. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11051188

Chicago/Turabian StyleFucà, Elisa, Floriana Costanzo, Luciana Ursumando, and Stefano Vicari. 2022. "Parenting Stress in Mothers of Children and Adolescents with Down Syndrome" Journal of Clinical Medicine 11, no. 5: 1188. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11051188

APA StyleFucà, E., Costanzo, F., Ursumando, L., & Vicari, S. (2022). Parenting Stress in Mothers of Children and Adolescents with Down Syndrome. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 11(5), 1188. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11051188