The State of Health and the Quality of Life in Women Suffering from Endometriosis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

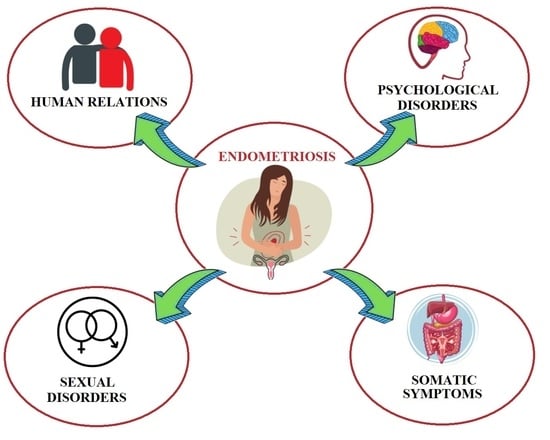

2. Quality of Life

3. Physical and Mental Symptoms of Endometriosis

4. Sexuality and Reproductive Health

5. Improvement in the Quality of Life and the State of Health

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tsamantioti, E.S.; Mahdy, H. Endometriosis; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2021. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK567777/ (accessed on 27 March 2022).

- Zondervan, K.T.; Becker, C.M.; Koga, K.; Missmer, S.A.; Taylor, R.N.; Viganò, P. Endometriosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2018, 4, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parasar, P.; Ozcan, P.; Terry, K.L. Endometriosis: Epidemiology, Diagnosis and Clinical Management. Curr. Obstet. Gynecol. Rep. 2017, 6, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- La Rosa, V.L.; Barra, F.; Chiofalo, B.; Platania, A.; Di Guardo, F.; Conway, F.; Di Angelo, A.S.; Lin, L.T. An overview on the relationship between endometriosis and infertility: The impact on sexuality and psychological well-being. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2020, 41, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cousins, F.L.; Dorien, F.O.; Gargett, C.E. Endometrial stem/progenitor cells and their role in the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2018, 50, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laganà, A.S.; Garzon, S.; Götte, M.; Viganò, P.; Franchi, M.; Ghezzi, F.; Martin, D.C. The Pathogenesis of Endometriosis: Molecular and Cell Biology Insights. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Soliman, A.M.; Fuldeore, M.; Snabes, M.C. Factors Associated with Time to Endometriosis Diagnosis in the United States. J. Women’s Health 2017, 26, 788–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arakawa, I.; Momoeda, M.; Osuga, Y.; Ota, I.; Koga, K. Cost-effectiveness of the recommended medical intervention for the treatment of dysmenorrhea and endometriosis in Japan. Cost Eff. Resour. Alloc. 2018, 16, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nnoaham, K.E.; Hummelshoj, L.; Webster, P.; d’Hooghe, T.; de Cicco Nardone, F.; de Cicco Nardone, C.; Jenkinson, C.; Kennedy, S.H.; Zondervan, K.T. World Endometriosis Research Foundation Global Study of Women’s Health Consortium. Impact of endometriosis on quality of life and work productivity: A multicenter study across ten countries. Fertil Steril. 2019, 112, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staal, A.H.J.; van der Zanden, M.; Nap, A.W. Diagnostic delay of endometriosis in the Netherlands. Gynecol. Obstet. Investig. 2016, 81, 321–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grangier, L.; Aerts, L.; Pluchino, N. Clinical investigation of Sexual pain in patients with endometriosis. Rev. Med. Suisse 2019, 15, 1941–1944. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.H.; Han, E. Endometriosis and Female Pelvic Pain. Semin. Reprod. Med. 2018, 36, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zarbo, C.; Brugnera, A.; Frigerio, L.; Malandrino, C.; Rabboni, M.; Bondi, E.; Compare, A. Behavioral, cognitive, and emotional coping strategies of women with endometriosis: A critical narrative review. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2018, 21, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machairiotis, N.; Vasilakaki, S.; Thomakos, N. Inflammatory Mediators and Pain in Endometriosis: A Systematic Review. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruber, T.M.; Mechsner, S. Pathogenesis of Endometriosis: The Origin of Pain and Subfertility. Cells 2021, 10, 1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcoverde, F.V.L.; Andres, M.P.; Borrelli, G.M.; Barbosa, P.A.; Abrão, M.S.; Kho, R.M. Surgery for Endometriosis Improves Major Domains of Quality of Life: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2019, 26, 266–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Fáveri, C.; Fermino, P.M.P.; Piovezan, A.P.; Volpato, L.K. The Inflammatory Role of Pro-Resolving Mediators in Endometriosis: An Integrative Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.K.; Chapron, C.; Giudice, L.C.; Laufer, M.R.; Leyland, N.; Missmer, S.A.; Singh, S.S.; Taylor, H.S. Clinical diagnosis of endometriosis: A call to action. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 220, e1–e354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bourdel, N.; Chauvet, P.; Billone, V.; Douridas, G.; Fauconnier, A.; Gerbaud, L.; Canis, M. Systematic review of quality-of-life measures in patients with endometriosis. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0208464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, K.; Brikci, N.; Erlaanga, D. Quality of Life, the Degree to Which an Individual Is Healthy, Comfortable, and Able to Participate in or Enjoy Life Events. 2016. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/topic/quality-of-life (accessed on 31 March 2022).

- Pirie, K.; Peto, R.; Green, J.; Beral, V. Health and Happiness. Lancet 2016, 387, 1251. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Xu, X.; Lin, L.; Xu, K.; Xu, M.; Ye, J.; Shen, X. Sexual function in patients with endometriosis: A prospective case-control study in China. J. Int. Med. Res. 2021, 49, 3000605211004388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muraham, R.; Amalia, T.; Pratama, G.; Harzif, A.K.; Agiananda, F.; Faidarti, M.; Azyati, M.; Sumapraja, K.; Winarto, H.; Wiweko, B.; et al. Chronic Pelvic Pain in Women with Endometriosis is Associated with Psychiatric Disorder and Quality of Life Deterioration. Int. J. Womens Health. 2022, 4, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bień, A.; Rzońca, E.; Zarajczyk, M.; Wilkosz, K.; Wdowiak, A.; Iwanowicz-Palus, G. Quality of life in women with endometriosis: A cross-sectional survey. Qual. Life Res. 2020, 29, 2669–2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warzecha, D.; Szymusik, I.; Wielgos, M.; Pietrzak, B. The impact of Endometriosis on the Quality of Life and the Incidence of Depression—A Cohort Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinlivan, J.; van den Berg, M. Managing the stigma and women’s physical and emotional cost of endometriosis. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 42, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andysz, A.; Jacukowicz, A.; Merecz-Kot, D.; Najder, A. Endometriosis—The challenge for occupational life of diagnosed women: A review of quantitative studies. Med. Pr. 2018, 69, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan-Myers, C.; Sherman, K.A.; Beath, A.P.; Duckworth, T.J.; Cooper, M.J.W. Delineating sociodemographic, medical and quality of life factors associated with psychological distress in individuals with endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 2021, 36, 2170–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Rosa, V.L.; De Franciscis, P.; Barra, F.; Schiattarella, A.; Török, P.; Shah, M.; Karaman, E.; Cerentini, M.T.; Di Guardo, F.; Gullo, G.; et al. Quality of life in women with endometriosis: A narrative overview. Minerva Med. 2020, 111, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, A.M.; Coyne, K.S.; Gries, K.S.; Castelli-Haley, J.; Snabes, M.C.; Surrey, E.S. The effect of endometriosis symptoms on absenteeism and presenteeism in the workplace and at home. J. Manag Care Spec. Pharm. 2017, 23, 745–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokrzywinski, R.M.; Soliman, A.M.; Chen, J.; Snabes, M.C.; Agarwal, S.K.; Coddington, C.; Coyne, K.S. Psychometric assessment of the health-related productivity questionnaire (HRPQ) among women with endometriosis. Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 2020, 20, 531–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rossi, V.; Tripodi, F.; Simonelli, C.; Galizia, R.; Nimbi, F.M. Endometriosis-associated pain: A review of quality of life, sexual health and couple relationship. Minerva Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 73, 536–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casalechi, M.; Vieira-Lopes, M.; Quessada, M.P.; Arão, T.C.; Reis, F.M. Endometriosis and related pelvic pain: Association with stress, anxiety and depressive symptoms. Minerva Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 73, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guidone, H.C. The Womb Wanders Not: Enhancing Endometriosis Education in a Culture of Menstrual Misinformation; Palgrave Macmillan: Singapore, 2020; Volume 22. [Google Scholar]

- Zarbo, C.; Brugnera, A.; Dessì, V.; Barbetta, P.; Candeloro, I.; Secomandi, R.; Betto, E.; Malandrino, C.; Bellia, A.; Trezzi, G.; et al. Cognitive and Personality Factors Implicated in Pain Experience in Women with Endometriosis: A Mixed-Method Study. Clin. J. Pain 2019, 35, 948–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Barneveld, E.; Manders, J.; van Osch, F.H.M.; van Poll, M.; Visser, L.; van Hanegem, N.; Lim, A.C.; Bongers, M.Y.; Leue, C. Depression, Anxiety, and Correlating Factors in Endometriosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Womens Health 2022, 31, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceran, M.U.; Yilmaz, N.; Ugurlu, E.N.; Erkal, N.; Ozgu-Erdinc, A.S.; Tasci, Y.; Gulerman, H.C.; Engin-Ustun, Y. Psychological domain of quality of life, depression and anxiety levels in in vitro fertilization/intracytoplasmic sperm injection cycles of women with endometriosis: A prospective study. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2020, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surrey, E.S.; Soliman, A.M.; Johnson, S.J.; Davis, M.; Castelli-Haley, J.; Snabes, M.C. Risk of developing comorbidities among women with endometriosis: A retrospective matched cohort study. J. Women’s Health 2018, 27, 1114–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verket, N.J.; Uhlig, T.; Sandvik, L.; Andersen, M.H.; Tanbo, T.G.; Qvigstad, E. Health-related quality of life in women with endometriosis, compared with the general population and women with rheumatoid arthritis. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2018, 97, 1339–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yudell, M.; Roberts, D.; DeSalle, R.; Tishkoff, S. Science and society. Taking race out of human genetics. Science 2016, 351, 564–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapron, C.; Lang, J.H.; Leng, J.H.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, X.; Xue, M.; Popov, A.; Romanov, V.; Maisonobe, P.; Cabri, P. Factors and regional differences associated with endometriosis: A multi-country, case-control study. Adv. Ther. 2016, 33, 1385–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, H.; Vannuccini, S.; Capezzuoli, T.; Ceccaroni, M.; Mubiao, L.; Shuting, H.; Wu, Y.; Huang, H.; Petraglia, F. Comorbidities and Quality of Life in Women Undergoing First Surgery for Endometriosis: Differences between Chinese and Italian Population. Reprod. Sci. 2021, 28, 2359–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yela, D.A.; Quagliato, I.P.; Benetti-Pinto, C.L. Quality of Life in Women with Deep Endometriosis: A Cross-Sectional Study. Rev. Bras. Ginecol. Obs. 2020, 42, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vannuccini, S.; Lazzeri, L.; Orlandini, C.; Morgante, G.; Bifulco, G.; Fagiolini, A.; Petraglia, F. Mental health, pain symptoms and systemic comorbidities in women with endometriosis: A cross-sectional study. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2018, 39, 315–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vannuccini, S.; Reis, F.M.; Coutinho, L.M.; Lazzeri, L.; Centini, G.; Petraglia, F. Surgical treatment of endometriosis: Prognostic factors for better quality of life. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2019, 35, 1010–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbara, G.; Facchin, F.; Buggio, L.; Somigliana, E.; Berlanda, N.; Kustermann, A.; Vercellini, P. What Is Known and Unknown about the Association between Endometriosis and Sexual Functioning: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Reprod. Sci. 2017, 24, 1566–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gater, A.; Taylor, F.; Seitz, C.; Gerlinger, C.; Wichmann, K.; Haberland, C. Development and content validation of two new patient-reported outcome measures for endometriosis: The Endometriosis Symptom Diary (ESD) and Endometriosis Impact Scale (EIS). J. Patient Rep. Outcomes 2020, 4, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Alcalde, A.M.; Martínez-Zamora, M.Á.; Gracia, M.; Ros, C.; Rius, M.; Carmona, F. Assessment of quality of sexual life in women with adenomyosis. J. Women Health 2021, 61, 520–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernays, V.; Schwartz, A.K.; Geraedts, K.; Rauchfuss, M.; Wölfler, M.M.; Haeberlin, F.; von Orelli, S.; Eberhard, M.; Imthurn, B.; Fink, D.; et al. Qualitative and quantitative aspects of sex life in the context of endometriosis: A multicentre case control study. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2020, 40, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahraki, Z.; Davar-Tanha, F.; Ghajarzadeh, M. Depression, sexual dysfunction and sexual quality of life in women with infertility. BMC Women’s Health 2018, 18, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, L.C.; Hsu, J.W.; Huang, K.L.; Bai, Y.M.; Su, T.P.; Li, C.T.; Yang, A.C.; Chang, W.H.; Chen, T.J.; Tsai, S.J.; et al. Risk of developing major depression and anxiety disorders among women with endometriosis: A longitudal follow-up study. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 190, 282–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, D.A.; Taylor, C.A. Dyspareunia in Women. Am. Fam. Physician 2021, 103, 597–604. [Google Scholar]

- Shum, L.K.; Bedaiwy, M.A.; Allaire, C.; Williams, C.; Noga, H.; Albert, A.; Lisonkova, S.; Yong, P.J. Deep Dyspareunia and Sexual Quality of Life in Women with Endometriosis. Sex. Med. 2018, 6, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zarbo, C.; Brugnera, A.; Compare, A.; Secomandi, R.; Candeloro, I.; Malandrino, C.; Betto, E.; Trezzi, G.; Rabboni, M.; Bondi, E.; et al. Negative metacognitive beliefs predict sexual distress over and above pain in women with endometriosis. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2019, 22, 575–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallagher, J.S.; DiVasta, A.D.; Vitonis, A.F.; Sarda, V.; Laufer, M.R.; Missmer, S.A. The impact of endometriosis on quality of life in adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 2018, 63, 766–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youseflu, S.; Sadatmahalleh, J.S.; Khomami, B.M.; Nasiri, M. Influential factors on sexual function in infertile women with endometriosis: A path analysis. BMC Womens Health 2020, 20, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukic, A.; Di Properzio, M.; De Carlo, S. Quality of sex life in endometriosis patients with deep dyspareunia before and after laparoscopic treatment. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2016, 293, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, K.E.; Lin, L.; Bruner, D.W. Sexual satisfaction and the importance of sexual health to quality of life throughout the life course of U.S. adults. J. Sex. Med. 2016, 13, 1642–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Turco, L.C.; Scaldaferri, F.; Chiantera, V.; Cianci, S.; Ercoli, A.; Fagotti, A.; Fanfani, F.; Ferrandina, G.; Nicolotti, N.; Tamburrano, A.; et al. Long-term evaluation of quality of life and gastrointestinal well-being after segmental colo-rectal resection for deep infiltrating endometriosis (ENDO-RESECT QoL). Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2020, 301, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comptour, A.; Pereira, B.; Lambert, C.; Chauvet, P.; Grémeau, A.S.; Pouly, J.L.; Canis, M.; Bourdel, N. Identification of Predictive Factors in Endometriosis for Improvement in Patient Quality of Life. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2020, 27, 712–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comptour, A.; Chauvet, P.; Canis, M.; Grémeau, A.S.; Pouly, J.L.; Rabischong, B.; Pereira, B.; Bourdel, N. Patient Quality of Life and Symptoms after Surgical Treatment for Endometriosis. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2019, 26, 717–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Márki, G.; Bokor, A.; Rigó, J.; Rigó, A. Physical pain and emotion regulation as the main predictive factors of health-related quality of life in women living with endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 2017, 32, 1432–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastu, E.; Celik, H.G.; Kocyigit, Y.; Yozgatli, D.; Yasa, C.; Ozaltin, S.; Tas, S.; Soylu, M.; Durbas, A.; Gorgen, H.; et al. Improvement in quality of life and pain scores after laparoscopic management of deep endometriosis: A retrospective cohort study. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2020, 302, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaghar, M.I. Evaluation of lifestyle and endometriosis in infertile women referring to the selected hospital of Tehran University Medical Sciences. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2019, 15, 3574–3577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boersen, Z.; de Kok, L.; van der Zanden, M.; Braat, D.; Oosterman, J.; Nap, A. Patients’ perspective on cognitive behavioural therapy after surgical treatment of endometriosis: A qualitative study. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2021, 42, 819–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aerts, L.; Grangier, L.; Streuli, I.; Dällenbach, P.; Marci, R.; Wenger, J.M.; Pluchino, N. Psychosocial impact of endometriosis: From co-morbidity to intervention. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2018, 50, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Florentino, A.V.A.; Pereira, A.M.G.; Martins, J.A.; Lopes, R.G.C.; Arruda, R.M. Quality of life assessment by the endometriosis health profile (EHP-30) questionnaire prior to treatment for ovarian endometriosis in Brazilian women. Rev. Bras. Ginecol. Obstet. 2019, 41, 548–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Marinho, M.C.P.; Magalhaes, T.F.; Fernandes, L.F.C.; Augusto, K.L.; Brilhante, A.V.M.; Bezerra, L.R.P.S. Quality of Life in Women with Endometriosis: An Integrative Review. J. Women’s Health 2018, 27, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rees, M.; Kiemle, G.; Slade, P. Psychological variables and quality of life in women with endometriosis. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2020, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ruszała, M.; Dłuski, D.F.; Winkler, I.; Kotarski, J.; Rechberger, T.; Gogacz, M. The State of Health and the Quality of Life in Women Suffering from Endometriosis. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 2059. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11072059

Ruszała M, Dłuski DF, Winkler I, Kotarski J, Rechberger T, Gogacz M. The State of Health and the Quality of Life in Women Suffering from Endometriosis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2022; 11(7):2059. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11072059

Chicago/Turabian StyleRuszała, Monika, Dominik Franciszek Dłuski, Izabela Winkler, Jan Kotarski, Tomasz Rechberger, and Marek Gogacz. 2022. "The State of Health and the Quality of Life in Women Suffering from Endometriosis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 11, no. 7: 2059. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11072059

APA StyleRuszała, M., Dłuski, D. F., Winkler, I., Kotarski, J., Rechberger, T., & Gogacz, M. (2022). The State of Health and the Quality of Life in Women Suffering from Endometriosis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 11(7), 2059. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11072059