Clinical Recommendations to Manage Gastrointestinal Adverse Events in Patients Treated with Glp-1 Receptor Agonists: A Multidisciplinary Expert Consensus

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. AEs Most Frequently Associated with GLP-1 RAs

4. Practical Guide to Follow When Initiating Treatment with GLP-1 RAs

4.1. Patient Education Prior to GLP-1 RA Start

4.2. Overall Procedures

- If GI AEs appear during the dose-escalating phase, HCPs could modify the planned schedule by implementing one or several of the following points [35,36]:

- ▪

- Extend the dose escalation phase duration (2–4 more weeks with the previous dose or temporary suspension).

- ▪

- Avoid dose escalation while GI AEs persist.

- ▪

- If a GI AE is experienced when moving up to a higher dose, go back on the lower one and stay on it for a few days. Then, increase the dose gradually, taking advantage of the multidose pen-injector when available.

- ▪

- In the case of persistent tolerability limitations set a dose lower than the maximum one recommended by the technical data sheet as a maintenance dose.

- ▪

- Withhold treatment temporarily until the resolution of AEs and then resume treatment.

- Start a differential diagnosis procedure to rule out underlying conditions causing the symptoms or their exacerbation [35].

- Start symptomatic treatment focused on the specific GI AE (see below).

- Switching to another GLP-1 RA may be considered. Although reported data from trials and real-world series do not show definitive differences between GLP-1 RAs in terms of tolerability (Table 1), there are studies claiming that the tolerability profile may vary between different compounds [1,33,39]. In fact, the switching strategy has already been proposed in the context of the treatment of people with T2D [40,41]. It is advisable to start the new GLP-1 RA at its lowest escalation dose. If the patient is on treatment with semaglutide, switching the route of administration, i.e., from s.c. to oral semaglutide or vice versa, may be an option [42].

4.3. Specific Procedures

4.3.1. Nausea

- ○

- ○

- If symptoms still persist, consider anti-emetic and/or prokinetic medications (Figure 4). Domperidone (10–20 mg three to four times daily, oral dosage, not in children < 12 years) should be used rather than metoclopramide, especially in older patients, to minimize the risk of extrapyramidal side effects [47]. Among substituted benzamides, cinitapride may be an alternative to metoclopramide [48]. In the event that oral semaglutide is being used, a period of 30 min must elapse between the administration of both medications. If drugs to mitigate nausea (or other GI AEs) are needed for over a month when the maintenance GLP-1 RA dose has been reached, a dose reduction should be considered for the patient to tolerate the drug with no need for pharmacological support [35].

4.3.2. Vomiting

- ○

- Maintaining hydration is particularly important.

- ○

- Small amounts of food should be taken in more frequent meals.

- ○

- Consider anti-emetic and/or prokinetic medications. Domperidone should be used rather than metoclopramide, as explained above [47].

- ○

- In case of persistence and/or remarkable severity, and where the patient presents with dizziness, confusion and fatigue, standard procedures to clinically manage severe vomiting can be initiated. Although rarely, intravenous rehydration may be necessary.

4.3.3. Diarrhoea

4.3.4. Constipation

5. Uncommon AEs

6. Myths or Reality?

6.1. Impact of GI AEs on Weight Loss

6.2. Patient Profiles Falsely Considered Unfit

6.2.1. Patients with Eating Disorders

6.2.2. Patients aged 75 Years Old or Older

6.2.3. Patients with Upper Gastrointestinal Disease

7. Clinical Scenarios of Interest

8. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nauck, M.A.; Quast, D.R.; Wefers, J.; Meier, J.J. GLP-1 receptor agonists in the treatment of type 2 diabetes—State-of-the-art. Mol. Metab. 2021, 46, 101102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Bloemendaal, L.; Ten Kulve, J.S.; la Fleur, S.E.; Ijzerman, R.G.; Diamant, M. Effects of glucagon-like peptide 1 on appetite and body weight: Focus on the CNS. J. Endocrinol. 2014, 221, T1–T16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Taha, M.B.; Yahya, T.; Satish, P.; Laird, R.; Agatston, A.S.; Cainzos-Achirica, M.; Patel, K.V.; Nasir, K. Glucagon-Like Peptide 1 Receptor Agonists: A Medication for Obesity Management. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2022, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honigberg, M.C.; Chang, L.S.; McGuire, D.K.; Plutzky, J.; Aroda, V.R.; Vaduganathan, M. Use of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease: A Review. JAMA Cardiol. 2020, 5, 1182–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, W.L.; Bain, S.C.; Min, T. The Effect of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists on Renal Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Ther. 2020, 11, 835–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dong, Y.; Lv, Q.; Li, S.; Wu, Y.; Li, L.; Li, J.; Zhang, F.; Sun, X.; Tong, N. Efficacy and safety of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Res. Hepatol. Gastroenterol. 2017, 41, 284–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aviles Bueno, B.; Soler, M.J.; Perez-Belmonte, L.; Jimenez Millan, A.; Rivas Ruiz, F.; Garcia de Lucas, M.D. Semaglutide in type 2 diabetes with chronic kidney disease at high risk progression-real-world clinical practice. Clin. Kidney J. 2022, 15, 1593–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattar, N.; Lee, M.; Kristensen, S.L.; Branch, K.; Del Prato, S.; Khurmi, N.S.; Lam, C.; Lopes, R.D.; McMurray, J.; Pratley, R.E.; et al. Cardiovascular, mortality, and kidney outcomes with GLP-1 receptor agonists in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021, 9, 653–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aroda, V.R.; Ahmann, A.; Cariou, B.; Chow, F.; Davies, M.J.; Jódar, E.; Mehta, R.; Woo, V.; Lingvay, I. Comparative efficacy, safety, and cardiovascular outcomes with once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide in the treatment of type 2 diabetes: Insights from the SUSTAIN 1-7 trials. Diabetes Metab. 2019, 45, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kushner, R.F.; Calanna, S.; Davies, M.; Dicker, D.; Garvey, W.T.; Goldman, B.; Lingvay, I.; Thomsen, M.; Wadden, T.A.; Wharton, S.; et al. Semaglutide 2.4 mg for the Treatment of Obesity: Key Elements of the STEP Trials 1 to 5. Obesity Silver Spring 2020, 28, 1050–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aroda, V.R.; Bauer, R.; Christiansen, E.; Haluzík, M.; Kallenbach, K.; Montanya, E.; Rosenstock, J.; Meier, J.J. Efficacy and safety of oral semaglutide by subgroups of patient characteristics in the PIONEER phase 3 programme. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2022, 24, 1338–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blonde, L.; Russell-Jones, D. The safety and efficacy of liraglutide with or without oral antidiabetic drug therapy in type 2 diabetes: An overview of the LEAD 1-5 studies. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2009, 11 (Suppl. 3), 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ard, J.; Cannon, A.; Lewis, C.E.; Lofton, H.; Vang Skjøth, T.; Stevenin, B.; Pi-Sunyer, X. Efficacy and safety of liraglutide 3.0 mg for weight management are similar across races: Subgroup analysis across the SCALE and phase II randomized trials. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2016, 18, 430–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jendle, J.; Grunberger, G.; Blevins, T.; Giorgino, F.; Hietpas, R.T.; Botros, F.T. Efficacy and safety of dulaglutide in the treatment of type 2 diabetes: A comprehensive review of the dulaglutide clinical data focusing on the AWARD phase 3 clinical trial program. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2016, 32, 776–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Grimm, M.; Han, J.; Weaver, C.; Griffin, P.; Schulteis, C.T.; Dong, H.; Malloy, J. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of exenatide once weekly in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: An integrated analysis of the DURATION trials. Postgrad. Med. 2013, 125, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klonoff, D.C.; Buse, J.B.; Nielsen, L.L.; Guan, X.; Bowlus, C.L.; Holcombe, J.H.; Wintle, M.E.; Maggs, D.G. Exenatide effects on diabetes, obesity, cardiovascular risk factors and hepatic biomarkers in patients with type 2 diabetes treated for at least 3 years. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2008, 24, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, W.; Wang, W.; Meng, R.; Wu, G.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, X.; Yin, H.; Zhu, D. Lixisenatide is effective and safe as add-on treatment to basal insulin in Asian individuals with type 2 diabetes and different body mass indices: A pooled analysis of data from the GetGoal Studies. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2021, 9, e002290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wharton, S.; Calanna, S.; Davies, M.; Dicker, D.; Goldman, B.; Lingvay, I.; Mosenzon, O.; Rubino, D.M.; Thomsen, M.; Wadden, T.A.; et al. Gastrointestinal tolerability of once-weekly semaglutide 2.4 mg in adults with overweight or obesity, and the relationship between gastrointestinal adverse events and weight loss. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2022, 24, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tofé, S.; Argüelles, I.; Mena, E.; Serra, G.; Codina, M.; Urgeles, J.R.; García, H.; Pereg, V. Real-world GLP-1 RA therapy in type 2 diabetes: A long-term effectiveness observational study. Endocrinol. Diabetes Metab. 2018, 2, e00051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tanaka, K.; Okada, Y.; Tokutsu, A.; Tanaka, Y. Real-world effectiveness of liraglutide versus dulaglutide in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes: A retrospective study. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Loreto, C.; Minarelli, V.; Nasini, G.; Norgiolini, R.; Del Sindaco, P. Effectiveness in Real World of Once Weekly Semaglutide in People with Type 2 Diabetes: Glucagon-Like Peptide Receptor Agonist Naïve or Switchers from Other Glucagon-Like Peptide Receptor Agonists: Results from a Retrospective Observational Study in Umbria. Diabetes Ther. 2022, 13, 551–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernando, K.; Bain, S.C.; Holmes, P.; Jones, P.N.; Patel, D.C. Glucagon-Like Peptide 1 Receptor Agonist Usage in Type 2 Diabetes in Primary Care for the UK and Beyond: A Narrative Review. Diabetes Ther. 2021, 12, 2267–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mody, R.; Yu, M.; Nepal, B.; Konig, M.; Grabner, M. Adherence and persistence among patients with type 2 diabetes initiating dulaglutide compared with semaglutide and exenatide BCise: 6-month follow-up from US real-world data. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2021, 23, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mody, R.; Huang, Q.; Yu, M.; Zhao, R.; Patel, H.; Grabner, M.; Landó, L.F. Adherence, persistence, glycaemic control and costs among patients with type 2 diabetes initiating dulaglutide compared with liraglutide or exenatide once weekly at 12-month follow-up in a real-world setting in the United States. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2019, 21, 920–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Uzoigwe, C.; Liang, Y.; Whitmire, S.; Paprocki, Y. Semaglutide Once-Weekly Persistence and Adherence versus Other GLP-1 RAs in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes in a US Real-World Setting. Diabetes Ther. 2021, 12, 1475–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Q.; Ouwens, M.J.; Grandy, S.; Johnsson, K.; Kostev, K. Adherence to GLP-1 receptor agonist therapy administered by once-daily or once-weekly injection in patients with type 2 diabetes in Germany. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2016, 9, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yu, M.; Xie, J.; Fernandez Lando, L.; Kabul, S.; Swindle, R.W. Liraglutide Versus Exenatide Once Weekly: Persistence, Adherence, and Early Discontinuation. Clin. Ther. 2016, 38, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rea, F.; Ciardullo, S.; Savaré, L.; Perseghin, G.; Corrao, G. Comparing medication persistence among patients with type 2 diabetes using sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors or glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in real-world setting. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2021, 180, 109035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampudia-Blasco, F.J.; Calvo Gómez, C.; Cos Claramunt, X.; García Alegría, J.; Jódar Gimeno, E.; Mediavilla Bravo, J.J.; Mezquita Raya, P.; Navarro Pérez, J.; Puig Domingo, M. Liraglutide in the treatment of type 2 diabetes: Recommendations for better patients’ selection from a multidisciplinary approach. Av. Diabetol. 2010, 26, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettge, K.; Kahle, M.; Abd El Aziz, M.S.; Meier, J.J.; Nauck, M.A. Occurrence of nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea reported as adverse events in clinical trials studying glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists: A systematic analysis of published clinical trials. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2017, 19, 336–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holst, J.J.; Andersen, D.B.; Grunddal, K.V. Actions of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor ligands in the gut. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2022, 179, 727–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svensson, A.M.; Toll, A.; Lebrec, J.; Miftaraj, M.; Franzén, S.; Eliasson, B. Treatment persistence in patients with type 2 diabetes treated with glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in clinical practice in Sweden. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2021, 23, 720–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, D.; Smith, A. Patient initiation and maintenance of GLP-1 RAs for treatment of obesity. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2021, 14, 1193–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Pérez, L.E.; Alvarez, M.; Dilla, T.; Gil-Guillén, V.; Orozco-Beltrán, D. Adherence to therapies in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Ther. 2013, 4, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wharton, S.; Davies, M.; Dicker, D.; Lingvay, I.; Mosenzon, O.; Rubino, D.M.; Pedersen, S.D. Managing the gastrointestinal side effects of GLP-1 receptor agonists in obesity: Recommendations for clinical practice. Postgrad. Med. 2022, 134, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreasen, C.R.; Andersen, A.; Knop, F.K.; Vilsbøll, T. Understanding the place for GLP-1RA therapy: Translating guidelines for treatment of type 2 diabetes into everyday clinical practice and patient selection. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2021, 23 (Suppl. 3), 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drucker, D.J.; Buse, J.B.; Taylor, K.; Kendall, D.M.; Trautmann, M.; Zhuang, D.; Porter, L.; DURATION-1 Study Group. Exenatide once weekly versus twice daily for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: A randomised, open-label, non-inferiority study. Lancet 2008, 372, 1240–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, J.J.; Rosenstock, J.; Hincelin-Méry, A.; Roy-Duval, C.; Delfolie, A.; Coester, H.V.; Menge, B.A.; Forst, T.; Kapitza, C. Contrasting effects of lixisenatide and liraglutide on postprandial glycemic control, gastric emptying, and safety parameters in patients with type 2 diabetes on optimized insulin glargine with or without metformin: A randomized, open-label trial. Diabetes Care 2015, 38, 1263–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nauck, M.A.; Meier, J.J. Management of Endocrine Disease: Are all GLP-1 agonists equal in the treatment of type 2 diabetes? Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2019, 181, R211–R234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Almandoz, J.P.; Lingvay, I.; Morales, J.; Campos, C. Switching Between Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists: Rationale and Practical Guidance. Clin. Diabetes 2020, 38, 390–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.B.; Ali, A.; Gorgojo Martínez, J.J.; Hramiak, I.; Kavia, K.; Madsbad, S.; Potier, L.; Prohaska, B.D.; Strong, J.L.; Vilsbøll, T. Switching between GLP-1 receptor agonists in clinical practice: Expert consensus and practical guidance. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2021, 75, e13731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kane, M.P.; Triplitt, C.L.; Solis-Herrera, C.D. Management of type 2 diabetes with oral semaglutide: Practical guidance for pharmacists. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2021, 78, 556–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, P.; Mishra, S.K.; Mithal, A.; Saxena, M.; Makkar, A.; Sharma, P. Clinical experience with Liraglutide in 196 patients with type 2 diabetes from a tertiary care center in India. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 18, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellido, D.; Abellán, P.; Ruiz Palomar, J.M.; Álvarez Sintes, R.; Nubiolae, A.; Bellido, V.; Romero, G.; Basal Lixi Study investigators. Intensification of Basal Insulin Therapy with Lixisenatide in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes in a Real-World Setting: The BASAL-LIXI Study. Curr. Ther. Res. Clin. Exp. 2018, 89, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitch, A.; Ingersoll, A.B. Patient initiation and maintenance of GLP-1 RAs for treatment of obesity: A narrative review and practical considerations for primary care providers. Postgrad. Med. 2021, 133, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahrén, B.; Atkin, S.L.; Charpentier, G.; Warren, M.L.; Wilding, J.; Birch, S.; Holst, A.G.; Leiter, L.A. Semaglutide induces weight loss in subjects with type 2 diabetes regardless of baseline BMI or gastrointestinal adverse events in the SUSTAIN 1 to 5 trials. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2018, 20, 2210–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ellero, C.; Han, J.; Bhavsar, S.; Cirincione, B.B.; Deyoung, M.B.; Gray, A.L.; Yushmanova, I.; Anderson, P.W. Prophylactic use of anti-emetic medications reduced nausea and vomiting associated with exenatide treatment: A retrospective analysis of an open-label, parallel-group, single-dose study in healthy subjects. Diabet. Med. 2010, 27, 1168–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Du, Y.; Su, T.; Song, X.; Gao, J.; Zou, D.; Zuo, C.; Xie, W.; Wang, B.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, J.; et al. Efficacy and safety of cinitapride in the treatment of mild to moderate postprandial distress syndrome-predominant functional dyspepsia. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2014, 48, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M.J.; Bergenstal, R.; Bode, B.; Kushner, R.F.; Lewin, A.; Skjøth, T.V.; Andreasen, A.H.; Jensen, C.B.; DeFronzo, R.A.; NN8022-1922 Study Group. Efficacy of Liraglutide for Weight Loss among Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: The SCALE Diabetes Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2015, 314, 687–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wharton, S.; Kuk, J.L.; Luszczynski, M.; Kamran, E.; Christensen, R. Liraglutide 3.0 mg for the management of insufficient weight loss or excessive weight regain post-bariatric surgery. Clin. Obes. 2019, 9, e12323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yabe, D.; Nakamura, J.; Kaneto, H.; Deenadayalan, S.; Navarria, A.; Gislum, M.; Inagaki, N.; PIONEER 10 Investigators. Safety and efficacy of oral semaglutide versus dulaglutide in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes (PIONEER 10): An open-label, randomised, active-controlled, phase 3a trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020, 8, 392–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, Y.; Katagiri, H.; Hamamoto, Y.; Deenadayalan, S.; Navarria, A.; Nishijima, K.; Seino, Y.; PIONEER 9 Investigators. Dose-response, efficacy, and safety of oral semaglutide monotherapy in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes (PIONEER 9): A 52-week, phase 2/3a, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020, 8, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trujillo, J. Safety and tolerability of once-weekly GLP-1 receptor agonists in type 2 diabetes. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2020, 45 (Suppl. 1), 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinberg, W.M.; Rosenstock, J.; Wadden, T.A.; Donsmark, M.; Jensen, C.B.; DeVries, J.H. Impact of Liraglutide on Amylase, Lipase, and Acute Pancreatitis in Participants with Overweight/Obesity and Normoglycemia, Prediabetes, or Type 2 Diabetes: Secondary Analyses of Pooled Data from the SCALE Clinical Development Program. Diabetes Care 2017, 40, 839–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marathe, C.S.; Rayner, C.K.; Jones, K.L.; Horowitz, M. Effects of GLP-1 and incretin-based therapies on gastrointestinal motor function. Exp. Diabetes Res. 2011, 2011, 279530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nexøe-Larsen, C.C.; Sørensen, P.H.; Hausner, H.; Agersnap, M.; Baekdal, M.; Brønden, A.; Gustafsson, L.N.; Sonne, D.P.; Vedtofte, L.; Vilsbøll, T.; et al. Effects of liraglutide on gallbladder emptying: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial in adults with overweight or obesity. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2018, 20, 2557–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi-Sunyer, X.; Astrup, A.; Fujioka, K.; Greenway, F.; Halpern, A.; Krempf, M.; Lau, D.C.; le Roux, C.W.; Violante Ortiz, R.; Jensen, C.B.; et al. SCALE Obesity and Prediabetes NN8022-1839 Study Group. A Randomized, Controlled Trial of 3.0 mg of Liraglutide in Weight Management. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, J.; Trautmann, M.E.; Haber, H.; Tham, L.S.; Hunt, T.; Mace, K.; Linnebjerg, H. Effect of exenatide on cholecystokinin-induced gallbladder emptying in fasting healthy subjects. Regul. Pept. 2012, 179, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storgaard, H.; Cold, F.; Gluud, L.L.; Vilsbøll, T.; Knop, F.K. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and risk of acute pancreatitis in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2017, 19, 906–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Shen, J.; Bala, M.M.; Busse, J.W.; Ebrahim, S.; Vandvik, P.O.; Rios, L.P.; Malaga, G.; Wong, E.; Sohani, Z.; et al. Incretin treatment and risk of pancreatitis in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised and non-randomised studies. BMJ 2014, 348, g2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Wang, J.; Ping, F.; Yang, N.; Huang, J.; Li, Y.; Xu, L.; Li, W.; Zhang, H. Association of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonist Use with Risk of Gallbladder and Biliary Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. JAMA Intern. Med. 2022, 182, 513–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayoub, W.A.; Kumar, A.A.; Naguib, H.S.; Taylor, H.C. Exenatide-induced acute pancreatitis. Endocr. Pract. 2010, 16, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedeño-Diaz, J.; Ruiz-Serrato, A.; Vallejo-Herrera, M.J.; Villar-Jimenez, J.; Gomez-Lora, D.; Garcia-Ordoñez, M.A. Pancreatitis aguda severa y precoz por liraglutide. Arch. Med. Int. 2014, 36, 119–121. [Google Scholar]

- Lingvay, I.; Hansen, T.; Macura, S.; Marre, M.; Nauck, M.A.; de la Rosa, R.; Woo, V.; Yildirim, E.; Wilding, J. Superior weight loss with once-weekly semaglutide versus other glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists is independent of gastrointestinal adverse events. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2020, 8, e001706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Porto, A.; Casarsa, V.; Colussi, G.; Catena, C.; Cavarape, A.; Sechi, L. Dulaglutide reduces binge episodes in type 2 diabetic patients with binge eating disorder: A pilot study. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2020, 14, 289–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, A.M.; Wadden, T.A.; Walsh, O.A.; Gruber, K.A.; Alamuddin, N.; Berkowitz, R.I.; Tronieri, J.S. Effects of Liraglutide and Behavioral Weight Loss on Food Cravings, Eating Behaviors, and Eating Disorder Psychopathology. Obesity Silver Spring 2019, 27, 2005–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, S.A.; Rohana, A.G.; Shah, S.A.; Chinna, K.; Wan Mohamud, W.N.; Kamaruddin, N.A. Improvement in binge eating in non-diabetic obese individuals after 3 months of treatment with liraglutide—A pilot study. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2015, 9, 301–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, S.; Shao, H. Anti-diabetic drugs and sarcopenia: Emerging links, mechanistic insights, and clinical implications. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2021, 12, 1368–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, D.P.; Kulstad, R.; Racine, N.; Shenker, Y.; Meredith, M.; Schoeller, D.A. Alterations in energy balance following exenatide administration. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2012, 37, 893–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seko, Y.; Sumida, Y.; Tanaka, S.; Mori, K.; Taketani, H.; Ishiba, H.; Hara, T.; Okajima, A.; Umemura, A.; Nishikawa, T.; et al. Effect of 12-week dulaglutide therapy in Japanese patients with biopsy-proven non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Hepatol. Res. 2017, 47, 1206–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.Y.; Park, K.Y.; Kim, B.J.; Hwang, W.M.; Kim, D.H.; Lim, D.M. Effects of short-term exenatide treatment on regional fat distribution, glycated hemoglobin levels, and aortic pulse wave velocity of obese type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Endocrinol. Metab. Seoul 2016, 31, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karagiannis, T.; Tsapas, A.; Athanasiadou, E.; Avgerinos, I.; Liakos, A.; Matthews, D.R.; Bekiari, E. GLP-1 receptor agonists and SGLT2 inhibitors for older people with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2021, 174, 108737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buch, A.; Marcus, Y.; Shefer, G.; Zimmet, P.; Stern, N. Approach to Obesity in the Older Population. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 106, 2788–2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perna, S.; Guido, D.; Bologna, C.; Solerte, S.B.; Guerriero, F.; Isu, A.; Rondanelli, M. Liraglutide and obesity in elderly: Efficacy in fat loss and safety in order to prevent sarcopenia. A perspective case series study. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2016, 28, 1251–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rockwood, K.; Song, X.; MacKnight, C.; Bergman, H.; Hogan, D.B.; McDowell, I.; Mitnitski, A. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ 2005, 173, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meier, J.J.; Granhall, C.; Hoevelmann, U.; Navarria, A.; Plum-Moerschel, L.; Ramesh, C.; Tannapfel, A.; Kapitza, C. Effect of upper gastrointestinal disease on the pharmacokinetics of oral semaglutide in subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2022, 24, 684–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, J.E.; Holst, J.J.; Jeppesen, P.B.; Kissow, H. GLP-1 and Intestinal Diseases. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maselli, D.B.; Camilleri, M. Effects of GLP-1 and Its Analogs on Gastric Physiology in Diabetes Mellitus and Obesity. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2021, 1307, 171–192. [Google Scholar]

- Halawi, H.; Khemani, D.; Eckert, D.; O’Neill, J.; Kadouh, H.; Grothe, K.; Clark, M.M.; Burton, D.D.; Vella, A.; Acosta, A.; et al. Effects of liraglutide on weight, satiation, and gastric functions in obesity: A randomised, placebo-controlled pilot trial. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 2, 890–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haywood, C.; Sumithran, P. Treatment of obesity in older persons-A systematic review. Obes. Rev. 2019, 20, 588–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donini, L.M.; Busetto, L.; Bischoff, S.C.; Cederholm, T.; Ballesteros-Pomar, M.D.; Batsis, J.A.; Bauer, J.M.; Boirie, Y.; Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Dicker, D.; et al. Definition and diagnostic criteria for sarcopenic obesity: ESPEN and EASO consensus statement. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 41, 990–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morillas, C.; D’Marco, L.; Puchades, M.J.; Solá-Izquierdo, E.; Gorriz-Zambrano, C.; Bermúdez, V.; Gorriz, J.L. Insulin Withdrawal in Diabetic Kidney Disease: What Are We Waiting For? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marbury, T.C.; Flint, A.; Jacobsen, J.B.; Derving Karsbøl, J.; Lasseter, K. Pharmacokinetics and Tolerability of a Single Dose of Semaglutide, a Human Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Analog, in Subjects with and without Renal Impairment. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2017, 56, 1381–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marso, S.P.; Daniels, G.H.; Brown-Frandsen, K.; Kristensen, P.; Mann, J.F.; Nauck, M.A.; Nissen, S.E.; Pocock, S.; Poulter, N.R.; Ravn, L.S.; et al. Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| GLP-1 RA | Program | Refs | Patient Profile | Dose | Method of Administration | Nausea | Vomiting | Diarrhoea | Constipation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Semaglutide | SUSTAIN | 9 | T2D | 1 mg | s.c. once weekly | 15–24 | 7–15 | 7–19 | 4–7 |

| Semaglutide | STEP | 10 | Obesity * | 2.4 mg | s.c. once weekly | 14–58 | 22–27 | 10–36 | 12–37 |

| Semaglutide | PIONEER | 11 | T2D | 14 mg | p.o. SID | 8–23 | 6–12 | 5–15 | 7–12 |

| Liraglutide | LEAD | 12 | T2D | 1.8 mg | s.c. SID | 10–40 | 4–17 | 8–19 | 11 |

| Liraglutide | SCALE | 13 | Obesity * | 3 mg | s.c. SID | 27–48 | 7–23 | 16–26 | 12–30 |

| Dulaglutide | AWARD | 14 | T2D | 1.5 mg | s.c. once weekly | 15–29 | 7–17 | 11–17 | n.r. |

| Exenatide | DURATION | 15 | T2D | 2 mg | s.c. once weekly | 5–14 | <1–6 | 5–11 | 1–8 |

| Exenatide | — | 16 | T2D | 10 µg | s.c. BID | 35–59 | 9–14 | 4–9 | 5 |

| Lixisenatide | GETGOAL | 17 | T2D | 20 µg | s.c. SID | 16–40 | 7–18 | 4–12 | 5† |

| Recommendations to Minimize Occurrence/Severity of GI AEs when Starting GLP-1 RA Therapy |

|---|

| General recommendations |

| Observe the guidelines of the data sheet regarding posology and method of administration |

| Improve eating habits |

| Eat slowly |

| Eat only if you are really hungry |

| Eat smaller portions |

| Avoid lying down after having a meal |

| Stop eating in case of feeling of fullness |

| Increase meal frequency |

| Avoid drinking using a straw |

| Eat without distractions and enjoy savouring the food |

| Try not to be too active after eating |

| Avoid eating too close to bedtime |

| Adapt food composition to your requirements |

| Choose easy-to-digest food, low fat diets (focus on bland foods) |

| Use oven, cooking griddle or boiling |

| Increase fluid intake, especially clear, fresh drinks (in small sips), but no so much as to make you feel too full |

| Healthy food that contain water (soups, liquid yogurt, gelatin, and others) |

| Avoid sweet meals |

| Avoid dressings, spicy foods, canned food, sauces that are not home-cooked |

| Get some fresh air and do some light exercise |

| Keep a food diary, as it may be useful to identify foods or meal timings that make it worse |

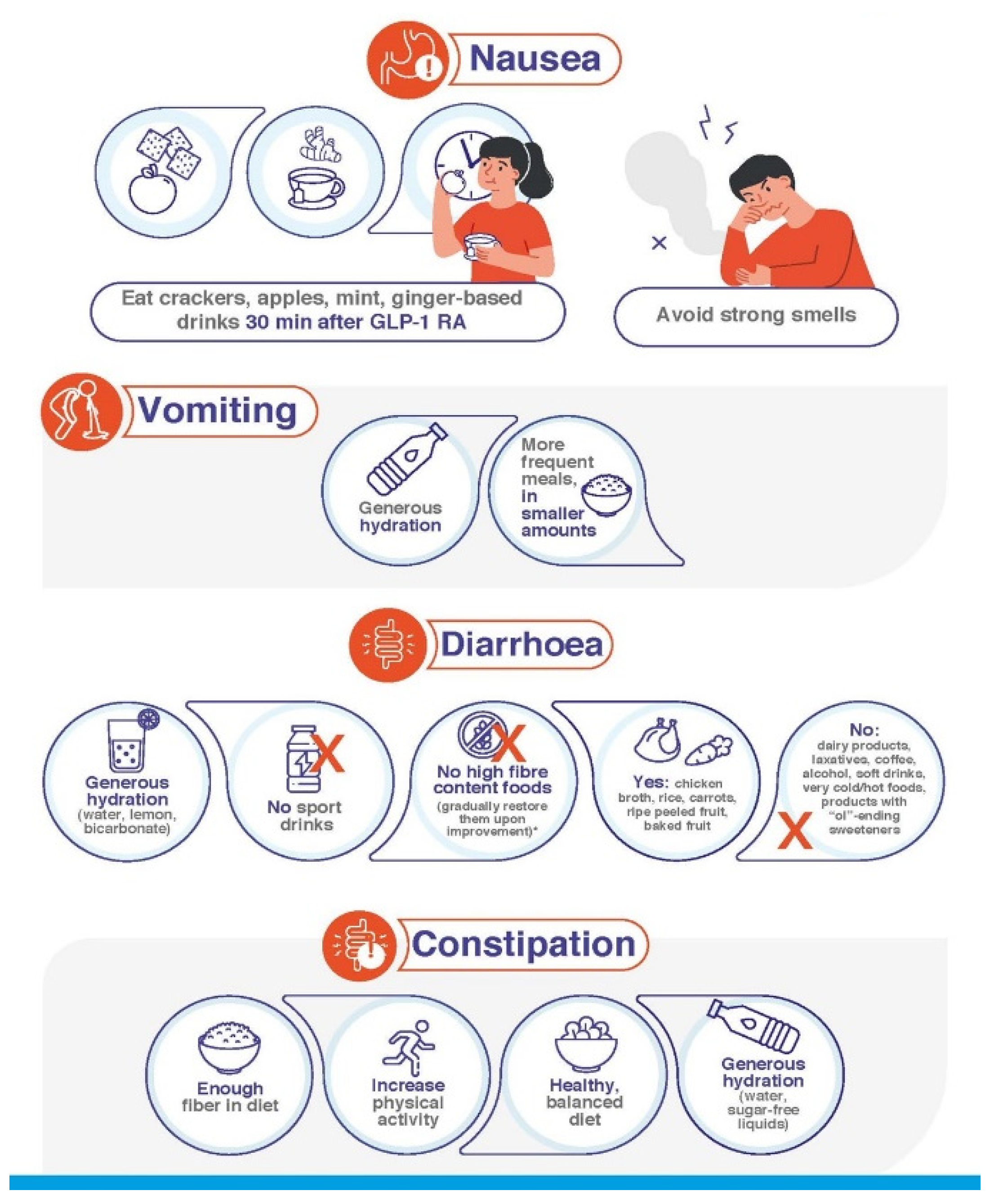

| Additional recommendations for patients with nausea |

| Provided that 30 min have passed since the last GLP-1 RA dose, eat foods able to ease the symptoms of nausea, such as crackers, apples, mint, ginger root or ginger-based drinks |

| Avoid strong smells |

| Additional recommendations for patients with vomiting |

| Be particularly careful with hydration |

| Eat smaller amounts of food in more frequent meals |

| Additional recommendations for patients with diarrhoea |

| Generous hydration, for example with water, lemon and a teaspoon of bicarbonate |

| Avoid isotonic drinks intended to be used in the context of sport activities |

| Avoid dairy products, laxative juices or meals, coffee, alcoholic drinks, soft drinks, very cold or very hot foods, products with sweeteners ending in “ol” (sorbitol, mannitol, xylitol, maltitol), including candy and gum |

| Avoid (or temporarily reduce your intake of) foods with high fibre content * such as grain and seed products, such as grain cereals, nuts, seeds, rice, barley, whole grain bread or baked goods vegetables such as artichokes, asparagus, beans, cabbage, cauliflower, garlic and garlic salts, lentils, mushrooms, onions, sugar snap, snow peas skinned fruits, apples, apricots, blackberries, cherries, mango, nectarines, pears, plums |

| Eat chicken broth, rice, carrots, very ripe fruit without skin |

| Additional recommendations for patients with constipation |

| Ensure the amount of fibre in your diet is adequate |

| Increase physical activity |

| Ensure your diet is healthy and balanced |

| Drink generous amounts of water (or other sugar-free liquids) |

| Additional recommendations when GLP-1 RA are unusually severe or/and persistent |

| In case of persistence of nausea and/or vomiting, avoid drinks during meals, rather have them between 30 and 60 min before and/or after meals |

| If nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea and/or constipation persist in spite of following all the guidelines depicted above, inform HCP as soon as possible |

| GLP-1 RA | Program | Refs | Target Patient | Dose | Administration | Cholelithiasis | AP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Semaglutide | SUSTAIN | 9 | T2D | 1 mg | s.c. once weekly | 0–2 | 0-<1 |

| Semaglutide | STEP | 10 | Obesity * | 2.4 mg | s.c. once weekly | <1–3 | 0-<1 |

| Semaglutide | PIONEER | 11 | T2D | 14 mg | p.o. QD | 0-<1 | 0-<1 |

| Liraglutide | LEAD | 12 | T2D | 1.8 mg | s.c. QD | 0 | 0-<1 |

| Liraglutide | SCALE | 13 | Obesity * | 3 mg | s.c. QD | <1–1 | 0-<1 |

| Dulaglutide | AWARD | 14 | T2D | 1.5 mg | s.c. once weekly | 0 | <1 |

| Exenatide | DURATION | 15 | T2D | 2 mg | s.c. once weekly | 0-<1 | 0-<1 |

| Exenatide | — | 16 | T2D | 10 µg | s.c. BID | 0 | 0 |

| Lixisenatide | GETGOAL | 17 | T2D | 20 µg | s.c. QD | 0 | 0 |

| Scenario 1. Persistent Nausea in Middle-Aged Patients |

|---|

| Female patient, 52 y.o., T2D, 6 years’ duration on metformin treatment. The patient starts oral semaglutide 3 mg OD without having received guidelines to prevent GI AEs. Four weeks later, the dose is increased to 7 mg OD, and 4 weeks later, to 14 mg OD. Since then, occasional intense episodes of nausea associated with eating large meals that include fatty foods occur. The dose is maintained at 14 mg OD for 2 months, at the end of which HbA1c improves from 7.8% to 7.3% and weight decreases by 3.7 kg (BMI 29.7 kg/m2), but nausea episodes persist. |

| Recommended clinical decision |

|

| Follow-up |

| The patient begins to apply the diet and lifestyle recommendations and starts taking domperidone before main meals. After 4 days, domperidone is not required anymore. Three months afterward, the patient reports decreased appetite without nausea. Additional decreases in HbA1c (6.8%) and weight (7% of the initial one, BMI 28.9 kg/m2), are achieved. |

| Comment |

| Before starting treatment with GLP-1 RA, the patient has to receive information on dietary recommendations to prevent GI AEs. If, even after applying these measures, the patient experiences nausea, temporary anti-emetic and/or prokinetic medications may be useful. |

| Scenario 2. Heartburn after GLP1-RA up-titration |

| Male patient, 63 y.o., BMI 34.5 kg/m2, with a history of gastroesophageal reflux subsequent to hiatal hernia treated with alkaline salts and with PPIs (omeprazole) for large meals. The patient comes to consultation to manage obesity. Liraglutide treatment is started following the recommended dose-escalation protocol, with weekly dose increases. When 1.8 mg OD is reached, the patient reports gastrointestinal symptoms after meals, namely postprandial heaviness, frequent eructation and heartburn, especially before bedtime. |

| Recommended clinical decision |

|

|

|

| Follow-up |

| Shortly after following the advised habits and pharmacological treatment, gastroesophageal reflux symptoms notably improved. After 2 weeks of maintaining liraglutide at 1.8 mg OD, dose-escalation is resumed at 2-week intervals, until the maximum effective dose of 3 mg OD is reached. Six months after treatment start, weight loss is 8.2% (BMI 31.7 kg/m2). |

| Comment |

| Gastroesophageal reflux is common in obesity. GLP-1 RAs have occasionally been described to exacerbate its symptoms, possibly because of the transient delay in gastric emptying subsequent to treatment initiation [78,79]. Suitable diet habits and PPI use are usually enough to relieve symptoms. Furthermore, these improve as weight decreases. Thus, there is no need to keep pharmacological support for a long time. |

| Scenario 3. Elderly patients with GI AEs subsequent to GLP-1 RA initiation |

| Female patient, 80 y.o., 98 kg, BMI 39.2 kg/m2, T2D with HbA1c 7.2%. The current treatment is metformin 850 mg BID/sitagliptin 100 mg OD. Weight loss is required before knee prosthesis placement. Previous attempts were unsuccessful. Sitagliptin is suspended and s.c. semaglutide is started, escalating doses every 4 weeks. When 0.5 mg/wk is reached, moderate to severe GI AEs appear (persistent nausea, postprandial vomiting several times a week, pronounced hyporexia). Symptoms persist for 2 months. Three months after semaglutide start, weight loss is 14 kg; the patient reports overall weakness and sarcopenia is diagnosed according to chair stand and timed-up-and-go tests, dinamometry and bioelectrical impedance analysis. |

| Recommended clinical decision |

|

|

| Follow-up |

| Semaglutide is maintained at 0.25 mg/wk, and GI AEs are not reported. Sarcopenia tests improve in 2 months. After 6 months, patient weight is 82 kg (BMI 32.8 kg/m2), and HbA1c decreases to 5.9%. Knee surgery is undertaken with no complications. |

| Comment |

| Obesity is common in the elderly, with GI AE onset being earlier and more severe. The scarce experience with GLP-1 RA in >75 y.o. patients invites us to start low and go slow. Sarcopenia risk must be assessed before and during GLP-1 RA treatment since the sharp weight loss in the elderly may be in part at the expense of lean mass [80,81]. |

| Scenario 4. Insulin-treated elderly people with T2D, obesity and CKD |

| Male patient, 76 y.o., BMI 32.0 kg/m2, poorly controlled T2D (HbA1c 8.9%), retinopathy and autonomic neuropathy, CKD with eGFR 25 mL/min/1.73 m2 and albumin-to-creatinine ratio 658 mg/g. The treatment consisted of linagliptin, dapagliflozin, atorvastatin and antihypertensive drugs. Baseline s.c. insulin degludec 0.2 U/kg before breakfast is started. Three months later, HbA1c is 7.5%. Linagliptin is suspended and s.c. semaglutide 0.25 mg/wk is started. The dose is increased to 0.5 mg/wk one month later. Two weeks later, the patient presents with 4–5 daily episodes of diarrhoea regardless of food composition. |

| Recommended clinical decision |

|

|

|

| Follow-up |

| Four months after semaglutide dose is set at 0.5 mg/wk, metabolic and CKD parameters improve (HbA1c 6.1%, albumin-to-creatinine ratio 310 mg/g), and BMI decreases to 28.0 kg/m2. No new GI AEs are reported. The patient did not require insulin treatment. |

| Comment |

| Semaglutide exposure is not influenced by renal impairment [83], and thus it is a suitable choice for T2D patients with CKD and obesity. CKD and autonomic neuropathy cause gastroparesis, thus increasing GI AE risk. CKD increases the risk of GLP-1 RA-associated diarrhoea, with symptoms being more severe with albuminuria [84]. Despite GI AEs may be frequent in the first weeks, attempts to alleviate symptoms are worthwhile: withdrawal risk decreases; thus, patients benefit from cardiorrenal protection and efficient metabolic control, which may allow reducing the intensity of insulin treatment, thus minimizing hypoglycaemia risk [82]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gorgojo-Martínez, J.J.; Mezquita-Raya, P.; Carretero-Gómez, J.; Castro, A.; Cebrián-Cuenca, A.; de Torres-Sánchez, A.; García-de-Lucas, M.D.; Núñez, J.; Obaya, J.C.; Soler, M.J.; et al. Clinical Recommendations to Manage Gastrointestinal Adverse Events in Patients Treated with Glp-1 Receptor Agonists: A Multidisciplinary Expert Consensus. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12010145

Gorgojo-Martínez JJ, Mezquita-Raya P, Carretero-Gómez J, Castro A, Cebrián-Cuenca A, de Torres-Sánchez A, García-de-Lucas MD, Núñez J, Obaya JC, Soler MJ, et al. Clinical Recommendations to Manage Gastrointestinal Adverse Events in Patients Treated with Glp-1 Receptor Agonists: A Multidisciplinary Expert Consensus. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(1):145. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12010145

Chicago/Turabian StyleGorgojo-Martínez, Juan J., Pedro Mezquita-Raya, Juana Carretero-Gómez, Almudena Castro, Ana Cebrián-Cuenca, Alejandra de Torres-Sánchez, María Dolores García-de-Lucas, Julio Núñez, Juan Carlos Obaya, María José Soler, and et al. 2023. "Clinical Recommendations to Manage Gastrointestinal Adverse Events in Patients Treated with Glp-1 Receptor Agonists: A Multidisciplinary Expert Consensus" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 1: 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12010145

APA StyleGorgojo-Martínez, J. J., Mezquita-Raya, P., Carretero-Gómez, J., Castro, A., Cebrián-Cuenca, A., de Torres-Sánchez, A., García-de-Lucas, M. D., Núñez, J., Obaya, J. C., Soler, M. J., Górriz, J. L., & Rubio-Herrera, M. Á. (2023). Clinical Recommendations to Manage Gastrointestinal Adverse Events in Patients Treated with Glp-1 Receptor Agonists: A Multidisciplinary Expert Consensus. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(1), 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12010145