Evaluation of the Michigan Clinical Consultation and Care Program: An Evidence-Based Approach to Perinatal Mental Healthcare

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Aims

1.2. Background

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Setting

2.3. Participants

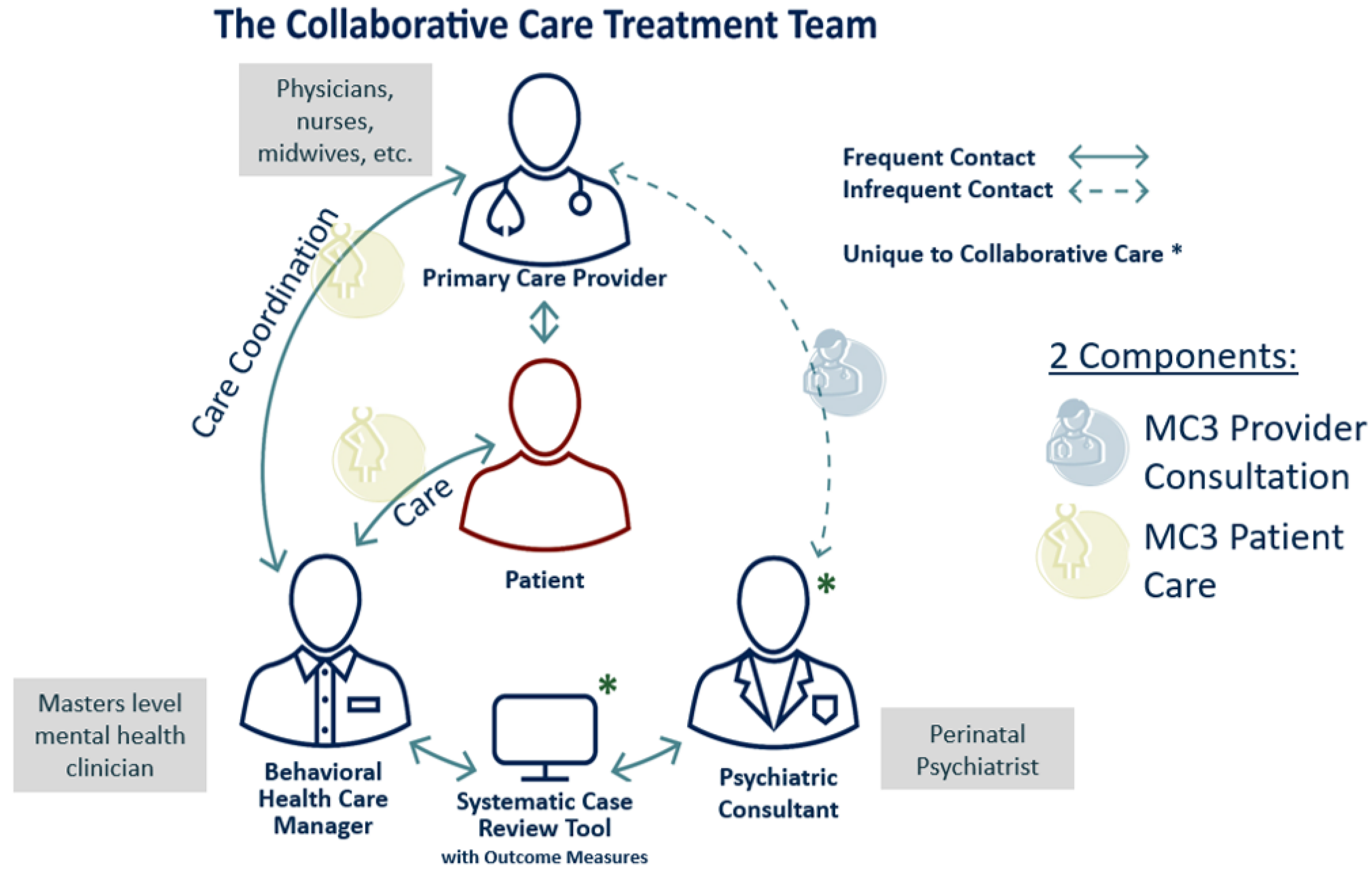

2.4. Program

2.5. Data Collection

2.6. Data Analysis

2.7. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Participant and Program Descriptors

3.1.1. Outreach and Treatment Sessions

3.1.2. Participant Satisfaction

3.1.3. Retention in Treatment

3.2. Mental Health Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Byatt, N.; Masters, G.A.; Bergman, A.L.; Moore Simas, T.A. Screening for Mental Health and Substance Use Disorders in Obstetric Settings. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2020, 22, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postpartum Support International. Depression during Pregnancy & Postpartum. Available online: https://www.postpartum.net/learn-more/depression/ (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Howard, L.M.; Khalifeh, H. Perinatal mental health: A review of progress and challenges. World Psychiatry 2020, 19, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, C.C.; Adams, C.E.; George, K.E.; Moore, J.E. Mental Health Conditions Increase Severe Maternal Morbidity by 50 Percent and Cost $102 Million Yearly in the United States: Study estimates hospitalization cost, length of stay, and severe maternal morbidity associated with perinatal mental health disorders. Health Aff. 2021, 40, 1575–1584. [Google Scholar]

- Wisner, K.L.; Sit, D.K.Y.; McShea, M.C.; Rizzo, D.M.; Zoretich, R.A.; Hughes, C.L.; Eng, H.F.; Luther, J.F.; Wisniewski, S.R.; Costantino, M.L.; et al. Onset timing, thoughts of self-harm, and diagnoses in postpartum women with screen-positive depression findings. JAMA Psychiatry 2013, 70, 490–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Admon, L.K.; Dalton, V.K.; Kolenic, G.E.; Ettner, S.L.; Tilea, A.; Haffajee, R.L.; Brownlee, R.M.; Zochowski, M.K.; Tabb, K.M.; Muzik, M.; et al. Trends in Suicidality 1 Year Before and After Birth Among Commercially Insured Childbearing Individuals in the United States, 2006–2017. JAMA Psychiatry 2021, 78, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araji, S.; Griffin, A.; Dixon, L.; Spencer, S.-K.; Peavie, C.; Wallace, K. An overview of maternal anxiety during pregnancy and the post-partum period. J. Ment. Health Clin. Psychol. 2020, 4, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimmel, M. Maternal Mental Health MATTERS. N. Carol. Med. J. 2020, 81, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, E.Q.; Sowa, N.A.; Meltzer-Brody, S.E.; Gaynes, B.N. The Perinatal Depression Treatment Cascade: Baby Steps Toward Improving Outcomes. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2016, 77, 1189–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Torteya, C.; Katsonga-Phiri, T.; Rosenblum, K.L.; Hamilton, L.; Muzik, M. Postpartum depression and resilience predict parenting sense of competence in women with childhood maltreatment history. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2018, 21, 777–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinnis, R.S.; McGinnis, E.W.; Hruschak, J.; Lopez-Duran, N.L.; Fitzgerald, K.; Rosenblum, K.L.; Muzik, M. Rapid detection of internalizing diagnosis in young children enabled by wearable sensors and machine learning. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0210267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinnis, E.W.; Anderau, S.P.; Hruschak, J.; Gurchiek, R.D.; Lopez-Duran, N.L.; Fitzgerald, K.; Rosenblum, K.L.; Muzik, M.; McGinnis, R.S. Giving voice to vulnerable children: Machine learning analysis of speech detects anxiety and depression in early childhood. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2019, 23, 2294–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebel, C.; MacKinnon, A.; Bagshawe, M.; Tomfohr-Madsen, L.; Giesbrecht, G. Elevated depression and anxiety symptoms among pregnant individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motrico, E.; Bina, R.; Domínguez-Salas, S.; Mateus, V.; Contreras-García, Y.; Carrasco-Portiño, M.; Ajaz, E.; Apter, G.; Christoforou, A.; Dikmen-Yildiz, P.; et al. Impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on perinatal mental health (Riseup-PPD-COVID-19): Protocol for an international prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avena, N.M.; Simkus, J.; Lewandowski, A.; Gold, M.S.; Potenza, M.N. Substance use disorders and behavioral addictions during the COVID-19 pandemic and covid-19-related restrictions. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 653674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; McDonnell, D.; Roth, S.; Li, Q.; Šegalo, S.; Shi, F.; Wagers, S. Mental health solutions for domestic violence victims amid COVID-19: A review of the literature. Glob. Health 2021, 17, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, L.M.; Wilson, C.A.; Chandra, P.S. Intimate partner violence and mental health: Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. World Psychiatry 2022, 21, 311–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byatt, N.; Yonkers, K.A. Addressing Maternal Mental Health: Progress, Challenges, and Potential Solutions. Psychiatr. News 2021, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterman, M.J.K.; Martin, J.A. Timing and Adequacy of Prenatal Care in the United States, 2016. Natl. Vital Stat. Rep. 2018, 67, 1–14. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr67/nvsr67_03.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- Mehralizade, A.; Schor, S.; Coleman, C.M.; Oppenheim, C.E.; Denckla, C.A.; Borba, C.P.; Henderson, D.C.; Wolff, J.; Crane, S.; Nettles-Gomez, P.; et al. Mobile Health Apps in OB-GYN-Embedded Psychiatric Care: Commentary. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2017, 5, e152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melville, J.L.; Reed, S.D.; Russo, J.; Croicu, C.A.; Ludman, E.; LaRocco-Cockburn, A.; Katon, W. Improving care for depression in obstetrics and gynecology: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 123, 1237–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- National Alliance on Mental Health. The Doctor Is Out. Available online: https://www.nami.org/Support-Education/Publications-Reports/Public-Policy-Reports/The-Doctor-is-Out (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- Byatt, N.D.; Straus, J.; Stopa, A.B.; Biebel, K.; Mittal, L.; Simas, T.A.M.M. Massachusetts Child Psychiatry Access Program for Moms: Utilization and Quality Assessment. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 132, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- University of Washington. MOMCare. Available online: http://depts.washington.edu/momcare/ (accessed on 25 September 2021).

- AIMS Center Advancing Integrated Mental Health Solutions. Collaborative Care for High Risk Mothers. Available online: https://aims.uw.edu/collaborative-care-high-risk-mothers (accessed on 25 September 2021).

- The Maternal-Infant Dyad Implementation (MIND-I) Initiative. Available online: https://aims.uw.edu/maternal-infant-dyad-implementation-mind-i-initiative (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- Marcus, S.; Malas, N.; Dopp, R.; Quigley, J.; Kramer, A.C.; Tengelitsch, E.; Patel, P.D. The Michigan Child Collaborative Care Program: Building a Telepsychiatry Consultation Service. Psychiatr. Serv. 2019, 70, 849–852, Erratum in Psychiatr. Serv. 2019, 70, 852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, P.; Panday, R. Psychoeducation an effective tool as treatment modality in mental health. Int. J. Indian Psychol. 2016, 4, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkhel, S.; Singh, O.; Arora, M. Clinical practice guidelines for psychoeducation in psychiatric disorders general principles of psychoeducation. Indian J. Psychiatry 2020, 62 (Suppl. 2), S319–S323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Neill, L.; Latchford, G.; McCracken, L.; Graham, C. The Acceptance and Commitment Therapy Fidelity Measure (ACT-FM) Form; ResearchGate: Berlin, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, R.A.; Goldstein, E. Mindfulness, Trauma, and Trance: A Mindfulness-Based Psychotherapeutic Approach. In The Wiley Blackwell Handbook of Mindfulness; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 649–687. [Google Scholar]

- Pollak, S.M.; Pollak, S.; Pedulla, T.; Siegel, R.D. Sitting Together: Essential Skills for Mindfulness-Based Psychotherapy; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro, R.T.; Trettim, J.P.; de Matos, M.B.; Pinheiro, K.A.T.; da Silva, R.A.; Martins, C.R.; da Cunha, G.K.; Coelho, F.T.; Motta, J.V.D.S.; Coelho, F.M.D.C.; et al. Brief cognitive behavioral therapy in pregnant women at risk of postpartum depression: Pre-post therapy study in a city in southern Brazil. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 290, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morelen, D.; Najm, J.; Wolff, M.; Daniel, K. Taking care of the caregivers: The moderating role of reflective supervision in the relationship between COVID-19 stress and the mental and professional well-being of the IECMH workforce. Infant Ment. Health J. 2022, 43, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menke, R.A.; Swanson, L.; Erickson, N.L.; Raglan, G.; Thompson, S.; Bullard, K.H.; Rosenblum, K.; Lopez, J.P.; Muzik, M. WIMH Group at University of Michigan Childhood adversity and sleep are associated with symptom severity in perinatal women presenting for psychiatric care. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2019, 22, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sameroff, A.J.; Seifer, R.; Baldwin, A.; Baldwin, C. Stability of intelligence from preschool to adolescence: The influence of social and family risk factors. Child Dev. 1993, 64, 80–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michigan Department of Health & Human Services. Health Care Programs Eligibility. Available online: https://www.michigan.gov/mdhhs/assistance-programs/medicaid/health-care-programs-eligibility (accessed on 30 June 2023).

- Attkisson, C.; Zwick, R. The client satisfaction questionnaire: Psychometric properties and correlations with service utilization and psychotherapy outcome. Eval. Program Plan. 1982, 5, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, E. The evolution and application of the 5 P’S behavioral risk screening tool. Source 2010, 20, 27–29. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). Resource Guide: Screening for Drug Use in General Medical Settings 2012. Available online: https://nida.nih.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/nmassist.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2023).

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.; Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhong, Q.-Y.; Gelaye, B.; Zaslavsky, A.M.; Fann, J.R.; Rondon, M.B.; Sánchez, S.E.; Williams, M.A. Diagnostic validity of the generalized anxiety disorder-7 (GAD-7) among pregnant women. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0125096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, E.; Rossom, R.C.; Henninger, M.; Groom, H.C.; Burda, B.U. Primary care screening for and treatment of depression in pregnant and postpartum women: Evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 2016, 315, 388–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhong, Q.; Gelaye, B.; Rondon, M.; Sánchez, S.E.; García, P.J.; Sánchez, E.; Barrios, Y.V.; Simon, G.E.; Henderson, D.C.; Cripe, S.M.; et al. Comparative performance of Patient Health Questionnaire-9 and Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale for screening antepartum depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2014, 162, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flynn, H.A.; Sexton, M.; Ratliff, S.; Porter, K.; Zivin, K. Comparative performance of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 in pregnant and postpartum women seeking psychiatric services. Psychiatry Res. 2011, 187, 130–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimidjian, S.; Goodman, S.H.; Felder, J.N.; Gallop, R.; Brown, A.P.; Beck, A. An open trial of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for the prevention of perinatal depressive relapse/recurrence. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2015, 18, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myors, K.A.; Johnson, M.; Cleary, M.; Schmied, V. Engaging women at risk for poor perinatal mental health outcomes: A mixed-methods study. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2015, 24, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, A.L.; Snider, E.M.; Prather, H.; Dougherty, N.L.; Wilcher-Roberts, M.; Hunt, D.M. Provider-Perceived Value of Interprofessional Team Meetings as a Core Element of a Lifestyle Medicine Program: A Mixed-Methods Analysis of One Center’s Experience. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, S.; Johnson, M.; Chambers, D.; Sutton, A.; Goyder, E.; Booth, A. The effects of integrated care: A systematic review of UK and international evidence. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blackmore, M.A.; Patel, U.B.; Stein, D.; Carleton, K.E.; Ricketts, S.M.; Ansari, A.M.; Chung, H. Collaborative Care for Low-Income Patients From Racial-Ethnic Minority Groups in Primary Care: Engagement and Clinical Outcomes. Psychiatr. Serv. 2022, 73, 842–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grote, N.K.; Katon, W.J.; Russo, J.E.; Lohr, M.J.; Curran, M.; Galvin, E.; Carson, K. Collaborative care for perinatal depression in socioeconomically disadvantaged women: A randomized trial. Depress. Anxiety 2015, 32, 821–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Black, D.S.; Amaro, H. Moment-by-Moment in Women’s Recovery (MMWR): Mindfulness-based intervention effects on residential substance use disorder treatment retention in a randomized controlled trial. Behav. Res. Ther. 2019, 120, 103437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClendon, J.; Dean, K.E.; Galovski, T. Addressing diversity in PTSD treatment: Disparities in treatment engagement and outcome among patients of color. Curr. Treat. Options Psychiatry 2020, 7, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alang, S.M. Mental health care among blacks in America: Confronting racism and constructing solutions. Health Serv. Res. 2019, 54, 346–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazroo, J.Y.; Bhui, K.S.; Rhodes, J. Where next for understanding race/ethnic inequalities in severe mental illness? Structural, interpersonal and institutional racism. Sociol. Health Illn. 2020, 42, 262–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taylor, R.E.; Kuo, B.C.H. Black American psychological help-seeking intention: An integrated literature review with recommendations for clinical practice. J. Psychother. Integr. 2019, 29, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fante-Coleman, T.; Jackson-Best, F. Barriers and facilitators to accessing mental healthcare in canada for black youth: A scoping review. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 2020, 5, 115–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chunara, R.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, J.; Lawrence, K.; Testa, P.; Nov, O.; Mann, D. Telemedicine and healthcare disparities: A cohort study in a large healthcare system in New York City during COVID-19. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2021, 28, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, V.A.; Harrison, J.M.; Williams, C.R.; Asiodu, I.V.; Ayala, S.; Getrouw-Moore, J.; Davis, N.K.; Davis, W.; Mahdi, I.K.; Nedhari, A.; et al. Reimagining Perinatal Mental Health: An Expansive Vision For Structural Change: Commentary describes changes needed to improve perinatal mental health care. Health Aff. 2021, 40, 1592–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaro, H.; Chernoff, M.; Brown, V.; Arévalo, S.; Gatz, M. Does integrated trauma-informed substance abuse treatment increase treatment retention? J. Community Psychol. 2007, 35, 845–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganetsky, V.S.P.; Heil, J.M.; Yates, B.; Jones, I.L.; Hunter, K.M.; Rivera, B.M.; Wilson, L.L.; Salzman, M.; Baston, K.E.M. A low-threshold comprehensive shared medical appointment program for perinatal substance use in an underserved population. J. Addict. Med. 2022, 16, e203–e209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galvin, S.L.; Ramage, M.; Mazure, E.; Coulson, C.C. The association of cannabis use late in pregnancy with engagement and retention in perinatal substance use disorder care for opioid use disorder: A cohort comparison. J. Subst. Abus. Treat. 2020, 117, 108098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dichter, M.E.; Sorrentino, A.E.; Haywood, T.N.; Tuepker, A.; Newell, S.; Cusack, M.; True, G. Women’s participation in research on intimate partner violence: Findings on recruitment, retention, and Participants’ experiences. Women’s Health Issues 2019, 29, 440–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gilroy, H.; McFarlane, J.; Maddoux, J.; Sullivan, C. Homelessness, housing instability, intimate partner violence, mental health, and functioning: A multi-year cohort study of IPV survivors and their children. J. Soc. Distress Homeless 2016, 25, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, M.; Chambers, J.E.; Denne, S.; Wiehe, S.E.; Tang, Q.; Park, S.; Litzelman, D. Associations of Mental Health Measures and Retention in a Community-Based Perinatal Care Recovery Support Program for Women of Childbearing Age With Substance Use Disorder. J. Dual Diagn. 2022, 18, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staudt, M. Best practices for enhancing substance abuse treatment retention by pregnant women. Best Pract. Ment. Health 2018, 14, 48–63. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, L.M.; Oram, S.; Galley, H.; Trevillion, K.; Feder, G. Domestic violence and perinatal mental disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2013, 10, e1001452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jasthi, D.L.; Nagle-Yang, S.; Frank, S.; Masotya, M.; Huth-Bocks, A. Associations between adverse childhood experiences and prenatal mental health and substance use among urban, low-income women. Community Ment. Health J. 2021, 58, 595–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| M/% | SD/n | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 29.92 | 5.51 |

| Race: White | 66.40 | 163 |

| Black | 29.55 | 74 |

| Asian | 2.02 | 5 |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0.74 | 2 |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 0.74 | 2 |

| Ethnicity: Hispanic or Latino | 5.44 | 13 |

| Insurance: Public | 47.23 | 110 |

| Private | 50.64 | 120 |

| Uninsured | 2.13 | 5 |

| Depression * | 52.86 | 111 |

| Anxiety * (score of 7+) | 76.08 | 159 |

| Anxiety * (score of 10+) | 59.81 | 125 |

| Interpersonal Violence Risk | 15.91 | 28 |

| Substance Use Risk | 35.00 | 63 |

| Outreach | M (SD)/% (n) |

|---|---|

| Days between referral and first outreach attempt | 1.54 (8.03) |

| Outreach attempts before contact | 2.09 (1.55) |

| Outreach attempts | |

| Texts | 64.44% (2197) |

| Calls | 18.22% (622) |

| Emails | 16.90% (577) |

| Video calls | 0.05% (18) |

| Outreaches resulting in response | 44.76% (1362) |

| Outreach time (min) | |

| 0–15 | 93.08% (2826) |

| 16–30 | 5.50% (167) |

| 31–45 | 0.86% (26) |

| 46–60 | 0.16% (5) |

| Disagree | Agree | |

|---|---|---|

| I am satisfied with the services that I received. | 3% | 97% |

| This program lived up to my expectations. | 3% | 97% |

| This program met my needs. | 6% | 94% |

| I would recommend this program to a friend if they were in need of similar help. | 3% | 97% |

| If I were to seek help again, I would come back to this program. | 3% | 97% |

| This program has helped me feel better equipped to handle the demands of this period in my life. | 6% | 94% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Muzik, M.; Menke, R.A.; Issa, M.; Fisk, C.; Charles, J.; Jester, J.M. Evaluation of the Michigan Clinical Consultation and Care Program: An Evidence-Based Approach to Perinatal Mental Healthcare. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4836. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12144836

Muzik M, Menke RA, Issa M, Fisk C, Charles J, Jester JM. Evaluation of the Michigan Clinical Consultation and Care Program: An Evidence-Based Approach to Perinatal Mental Healthcare. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(14):4836. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12144836

Chicago/Turabian StyleMuzik, Maria, Rena A. Menke, Meriam Issa, Chelsea Fisk, Jordan Charles, and Jennifer M. Jester. 2023. "Evaluation of the Michigan Clinical Consultation and Care Program: An Evidence-Based Approach to Perinatal Mental Healthcare" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 14: 4836. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12144836

APA StyleMuzik, M., Menke, R. A., Issa, M., Fisk, C., Charles, J., & Jester, J. M. (2023). Evaluation of the Michigan Clinical Consultation and Care Program: An Evidence-Based Approach to Perinatal Mental Healthcare. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(14), 4836. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12144836