Detecting Comparative Features of Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment through the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health Linkage: A Web-Based Survey

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Survey Questionnaire Details

2.3. Comparison with Other Multidimensional Geriatric Assessments

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Respondents

3.2. Aggregated Items of the Classical CGA Components

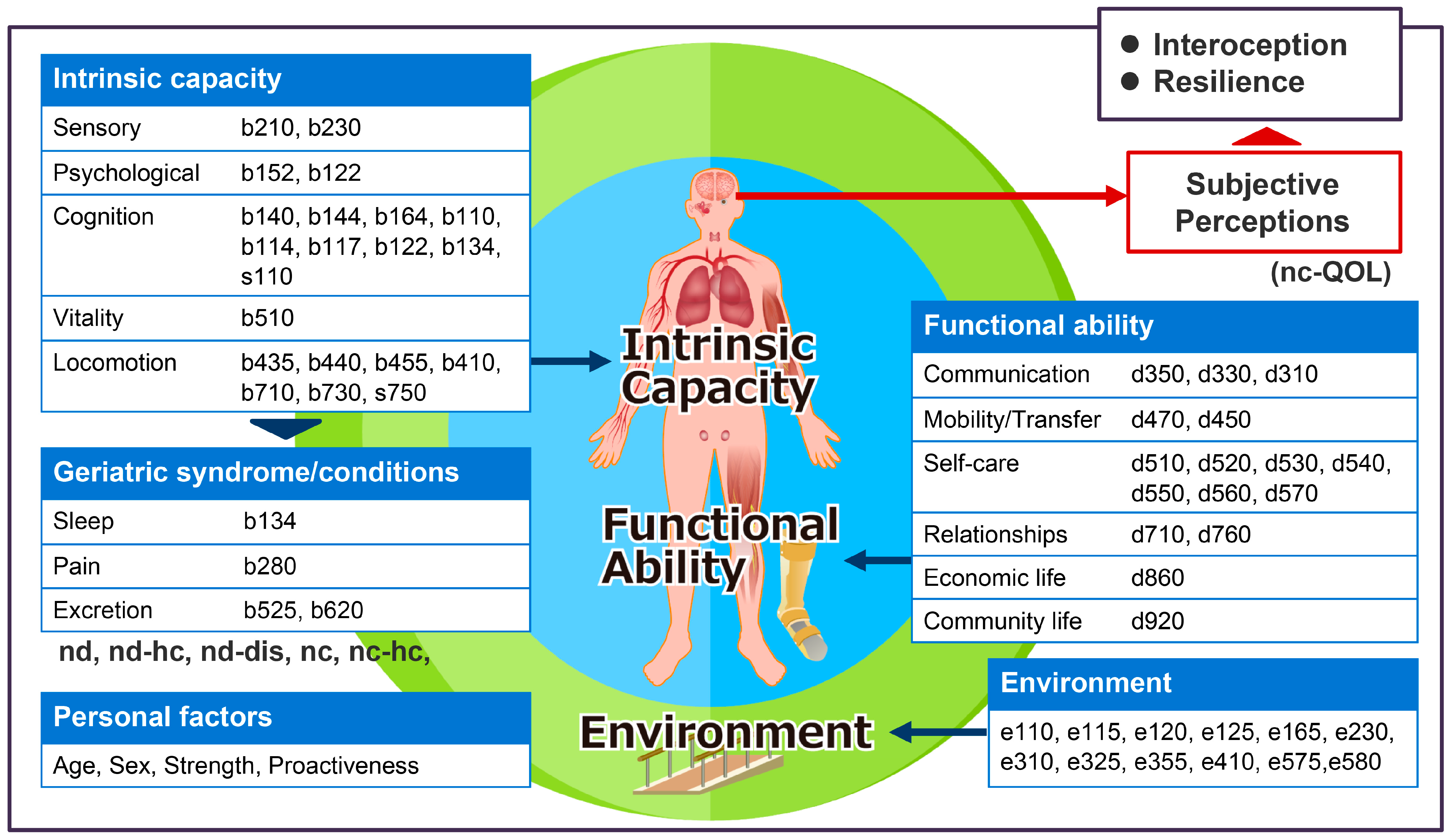

3.2.1. Categories Selected from the ICF Components

3.2.2. Open-Ended Question Responses for Inclusion in the CGA (Table 3)

3.3. Common Geriatric Concepts Selected for Inclusion in the CGA (Table 6)

3.4. Comparison of the Classical CGA Components with Existing Multidimensional Assessment Tools (Figure 2)

3.4.1. Comparison with the Geriatric ICF Core Set

3.4.2. Comparison with Frailty Criteria

3.4.3. Comparison with GA Tools for Clinical Oncology Criteria

3.4.4. Comparison of Not Defined/Not Covered (nd/nc) Items

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rubenstein, L.Z.; Rubenstein, L.V. Multidimensional Geriatric Assessment. In Brock-Lenhurst’s Textbook of Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology, 8th ed.; Fillit, H., Rockwood, K., Young, J.B., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; p. 216. [Google Scholar]

- Olde Rikkert, M.G. Conceptualizing Geriatric Syndromes. In Oxford Textbook of Geriatric Medicine, 3rd ed.; Michel, J.P., Beattie, B.L., Martin, F.C., Walston, J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 355–361. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. World Report on Aging and Health. 2015. Available online: https://www.who.int/ageing/events/world-report-2015-launch/en/ (accessed on 17 October 2020).

- Pilotto, A.; Panza, F. Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment. In Oxford Textbook of Geriatric Medicine, 3rd ed.; Michel, J.P., Beattie, B.L., Martin, F.C., Walston, J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 117–125. [Google Scholar]

- Fitch, M.I.; Strohschein, F.J.; Nyrop, K. Measuring Quality of Life in Older People with Cancer. Curr. Opin. Support. Palliat. Care 2021, 15, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Japanese Geriatric Society; Japanese Association for Home Care Medicine; National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology. Guidelines for Home Care Medicine and Care Services for Older Patients. Tokyo, Japan. 2019. Available online: https://minds.jcqhc.or.jp/n/med/4/med0380/G0001112 (accessed on 9 May 2023).

- Veronese, N.; Custodero, C.; Demurtas, J.; Smith, L.; Barbagallo, M.; Maggi, S.; Pilotto, A. Comprehensive geriatric assessment in older people: An umbrella review of health outcomes. Age Ageing 2022, 51, afac104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning Disability and Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/international-classification-of-functioning-disability-and-health (accessed on 10 July 2021).

- Bickenbach, J.; Cieza, A.; Racuch, A.; Stucki, G. ICF Core Sets: Manual for Clinical Practice; Hogrefe Publishing: Göttingen, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Grill, E.; Ewert, T.; Chatterji, S.; Kostanjsek, N.; Stucki, G. ICF core sets development for the acute hospital and early post-acute rehabilitation facilities. Disabil. Rehabil. 2005, 27, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grill, E.; Hermes, R.; Swoboda, W.; Uzarewicz, C.; Kostanjsek, N.; Stucki, G. ICF core set for geriatric patients in early post-acute rehabilitation facilities. Disabil. Rehabil. 2005, 27, 411–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stier-Jarmer, M.; Grill, E.; Müller, M.; Strobl, R.; Quittan, M.; Stucki, G. Validation of the comprehensive ICF core set for patients in geriatric post-acute rehabilitation facilities. J. Rehabil. Med. 2011, 43, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Grill, E.; Müller, M.; Quittan, M.; Strobl, R.; Kostanjsek, N.; Stucki, G. Brief ICF core set for patients in geriatric post-acute rehabilitation facilities. J. Rehabil. Med. 2011, 43, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Spoorenberg, S.L.; Reijneveld, S.A.; Middel, B.; Uittenbroek, R.J.; Kremer, H.P.; Wynia, K. The Geriatric ICF core set reflecting health-related problems in community-living older adults aged 75 years and older without dementia: Development and validation. Disabil. Rehabil. 2015, 37, 2337–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cieza, A.; Geyh, S.; Chatterji, S.; Kostanjsek, N.; Ustün, B.; Stucki, G. ICF linking rules: An update based on lessons learned. J. Rehabil. Med. 2005, 37, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cieza, A.; Fayed, N.; Bickenbach, J.; Prodinger, B. Refinements of the ICF linking rules to strengthen their potential for establishing comparability of health information. Disabil. Rehabil. 2019, 41, 574–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.; Sandford, B. The Delphi Technique: Making sense of consensus. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2007, 12, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzopardi, R.V.; Vermeiren, S.; Gorus, E.; Habbig, A.K.; Petrovic, M.; Van Den Noortgate, N.; De Vriendt, P.; Bautmans, I.; Beyer, I.; Gerontopole Brussels Study Group. Linking frailty instruments to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health: A systematic review. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2016, 17, 1066.e1–1066.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitnitski, A.B.; Mogilner, A.J.; Rockwood, K. Accumulation of deficits as a proxy measure of aging. Sci. World J. 2001, 1, 323–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Searle, S.D.; Mitnitski, A.; Gahbauer, E.A.; Gill, T.M.; Rockwood, K. A Standard procedure for creating a frailty index. BMC Geriatr. 2008, 8, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fried, L.P.; Tangen, C.M.; Walston, J.; Newman, A.B.; Hirsch, C.; Gottdiener, J.; Seeman, T.; Tracy, R.; Kop, W.J.; Burke, G.; et al. Frailty in older adults: Evidence for a phenotype. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2001, 56, M146–M156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wildiers, H.; Heeren, P.; Puts, M.; Topinkova, E.; Janssen-Heijnen, M.L.; Extermann, M.; Falandry, C.; Artz, A.; Brain, E.; Colloca, G.; et al. International Society of Geriatric Oncology Consensus on Geriatric Assessment in older patients with cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 2595–2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- de Vriendt, P.; Lambert, M.; Mets, T. Integrating the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) in the Geriatric Minimum Data Set-25 (GMDS-25) for Intervention Studies in Older People. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2009, 13, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballert, C.S.; Hopfe, M.; Kus, S.; Mader, L.; Prodinger, B. Using the Refined ICF linking rules to compare the content of existing instruments and assessments: A systematic review and exemplary analysis of instruments measuring participation. Disabil. Rehabil. 2019, 41, 584–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Integrated Care for Older People (ICOPE): Guidance for Person-Centred Assessment and Pathways in Primary Care; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, J.; Geary, H.; Millgate, E.; Catmur, C.; Bird, G. Direct and indirect effects of age on interoceptive accuracy and awareness across the adult lifespan. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2018, 25, 1193–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Larson, E.B. Enlightened Aging: Building Resilience for a Long, Active Life; Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Robben, S.M.; Pol, M.C.; Buurman, B.M.; Kröse, B.J.A. Expert knowledge for modeling functional health from sensor data. Methods Inf. Med. 2016, 55, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| No. | Questions Choose/Note Items for Assessing the Overall Health Profile | Response Methods |

|---|---|---|

| A1 | List of geriatric problems or concepts * (Geriatric syndromes/Geriatric conditions) | Check-all-that-apply |

| Note if you think of any other items regarding GS | Open-ended | |

| B1 | Activities and participation (d; ICF second category) | Check-all-that-apply |

| Note if you think of any other items regarding d | Open-ended | |

| B2 | Environmental factors (e; ICF second category) | Check-all-that-apply |

| Note if you think of any other items regarding e | Open-ended | |

| B3 | Body functions and structure (b, s; ICF second category) ** | Check-all-that-apply |

| Note if you think of any other items regarding b and s | Open-ended | |

| B4 | List of pfs | Check-all-that-apply |

| Note if you think of any other items regarding pf | Open-ended |

| Questions | Items |

|---|---|

| A1. Geriatric problems or concepts (Geriatric syndromes/conditions) | Social network, social support, social isolation, social participation, social role, life space, homebound, frailty, polypharmacy, and non-adherence |

| B4. Personal factors * | Sex, race, sex, age, strength, lifestyle, cultural customs, coping method, social background, education, occupation, personality, experience, and individual’s psychological characteristics |

| Round 1 n = 327 | Round 2 n = 182 | |

|---|---|---|

| Male/Female | 168/159 | 90/90 1 |

| Healthcare professionals | 80 (24.4%) | 53 (29.1%) |

| Geriatricians | 17 | 7 |

| Nurses | 23 | 22 |

| Therapists | 33 | 20 |

| Case managers | 7 | 4 |

| Non-professional older adults | 247 (75.6%) | 129 (70.9%) |

| Registered respondents | 242 | 126 |

| Convenience sampling | 5 | 3 |

| ICF Components | Selected ICF Categories |

|---|---|

| Body function (b) 1 | b140 (attention functions), b144 (memory functions), b152 (emotional functions), b164 (higher-level cognitive functions), b110 (consciousness functions), b114 (orientation functions), b117 (intellectual functions), b122 (lobal psychosocial functions), b134 (sleep functions), b210 (seeing functions), b230 (hearing functions), b280 (sensation of pain), b410 (heart functions), b435 (immunological system functions), b440 (respiration functions), b455 (exercise tolerance functions), b510 (ingestion functions), b525 (defecation functions), b620 (urination functions), b710 (mobility of joint functions), b730 (muscle power functions) |

| Body structure (s) 1 | s110 (structure of brain), s750 (structure of lower extremity) |

| Activities and participation (d) | d310 (communicating with—receiving spoken messages), d330 (speaking), d350 (conversation), d450 (walking), d470 (using transportation), d510 (washing oneself), d520 (caring for body parts), d530 (toileting), d540 (dressing), d550 (eating), d560 (drinking), d570 (looking after one’s health), d710 (basic interpersonal interactions), d760 (family relationships), d860 (basic economic transactions), d920 (recreations and leisure) |

| Environmental factors (e) | e110 (products or substances for personal consumption), e115 (products and technology for personal use in daily living), e120 (products and technology for personal indoor and outdoor mobility and transportation), e125 (products and technology for communication), e165 (assets), e230 (natural events), e310 (immediate family), e325 (acquaintances, peers, colleagues, neighbors, and community members), e355 (health professionals), e410 (individual attitudes of immediate family members), e575 (general social support services, systems and policies), e580 (health services, systems, and policies) |

| Personal factors (pf) 2 | Sex, age, strength |

| Classification by ICF Linking Rules 2016 | Answers 1 |

|---|---|

| nd | Adverse drug reactions |

| nd-hc | Health status |

| nd-dis | Falls, concomitant chronic diseases, hospital dependence |

| pf | Proactiveness |

| nc | Advanced care planning |

| nc-hc | Dementia, depression, sarcopenia, malnutrition, self-neglect |

| nc-QOL | QOL, life satisfaction, self-perception of social competence, Ikigai (the individual’s sense of meaning in life), perception of health status 2, self-evaluation 2, enjoying solitude 2, individual’s wishes 2, self-efficacy 2 |

| Items | Professional Respondents | Non-Professional Respondents | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medical Staff * | Case Manager | ||

| Social network | 38 (77.6) | 2 (50.0) | 59 (45.7) |

| Social support | 47 (95.9) | 3 (75.0) | 76 (58.9) |

| Social isolation | 21 (42.9) | 2 (50.0) | 37 (28.7) |

| Social participation | 45 (91.8) | 3 (75.0) | 76 (58.9) |

| Social role | 35 (71.4) | 2 (50.0) | 49 (38.0) |

| Life space | 34 (69.4) | 1 (25.0) | 63 (48.8) |

| Homebound | 31 (63.3) | 1 (25.0) | 45 (34.9) |

| Frailty | 35 (71.4) | 1 (25.0) | 26 (20.2) |

| Polypharmacy | 27 (55.1) | 0 (0) | 40 (31.0) |

| Non-adherence | 19 (38.8) | 4 (25.0) | 28 (21.7) |

| Assessment Set | Items |

|---|---|

| Classical CGA | pf (proactiveness), nd (adverse drug reactions), nc (advance care planning), nc-QOL (self-perception), nd-hc (health status), nc-hc, and nd-dis (geriatric syndromes and concomitant chronic disease) |

| ICF Core Set | - |

| Frailty phenotype | - |

| Kihon Check List | hc (physical strength), nc (house-boundness) |

| GFI | nc-hc (dementia), nd (number of medications) |

| FI-CGA | pf (social), nc-hc (comorbidity scale), hc (falls) |

| CGA-Frailty | nc-hc (comorbidity scale) |

| 70-item Frailty index | pf (family history), nc-hc (medical histories of some chronic disease), nc (other medical histories), nd (changes in everyday activities) |

| G8 | pf (age, health status), hc (number of neuropsychological problems), nc (number of medications) |

| VES-13 | pf (age, self-reported health) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tomita, N.; Ohashi, Y.; Ishiki, A.; Ozaki, A.; Nakao, M.; Ebihara, S.; Taki, Y. Detecting Comparative Features of Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment through the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health Linkage: A Web-Based Survey. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4917. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12154917

Tomita N, Ohashi Y, Ishiki A, Ozaki A, Nakao M, Ebihara S, Taki Y. Detecting Comparative Features of Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment through the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health Linkage: A Web-Based Survey. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(15):4917. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12154917

Chicago/Turabian StyleTomita, Naoki, Yuki Ohashi, Aiko Ishiki, Akiko Ozaki, Mitsuyuki Nakao, Satoru Ebihara, and Yasuyuki Taki. 2023. "Detecting Comparative Features of Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment through the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health Linkage: A Web-Based Survey" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 15: 4917. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12154917

APA StyleTomita, N., Ohashi, Y., Ishiki, A., Ozaki, A., Nakao, M., Ebihara, S., & Taki, Y. (2023). Detecting Comparative Features of Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment through the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health Linkage: A Web-Based Survey. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(15), 4917. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12154917