Contemporary Clinical Profile of Left-Sided Native Valve Infective Endocarditis: Influence of the Causative Microorganism

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

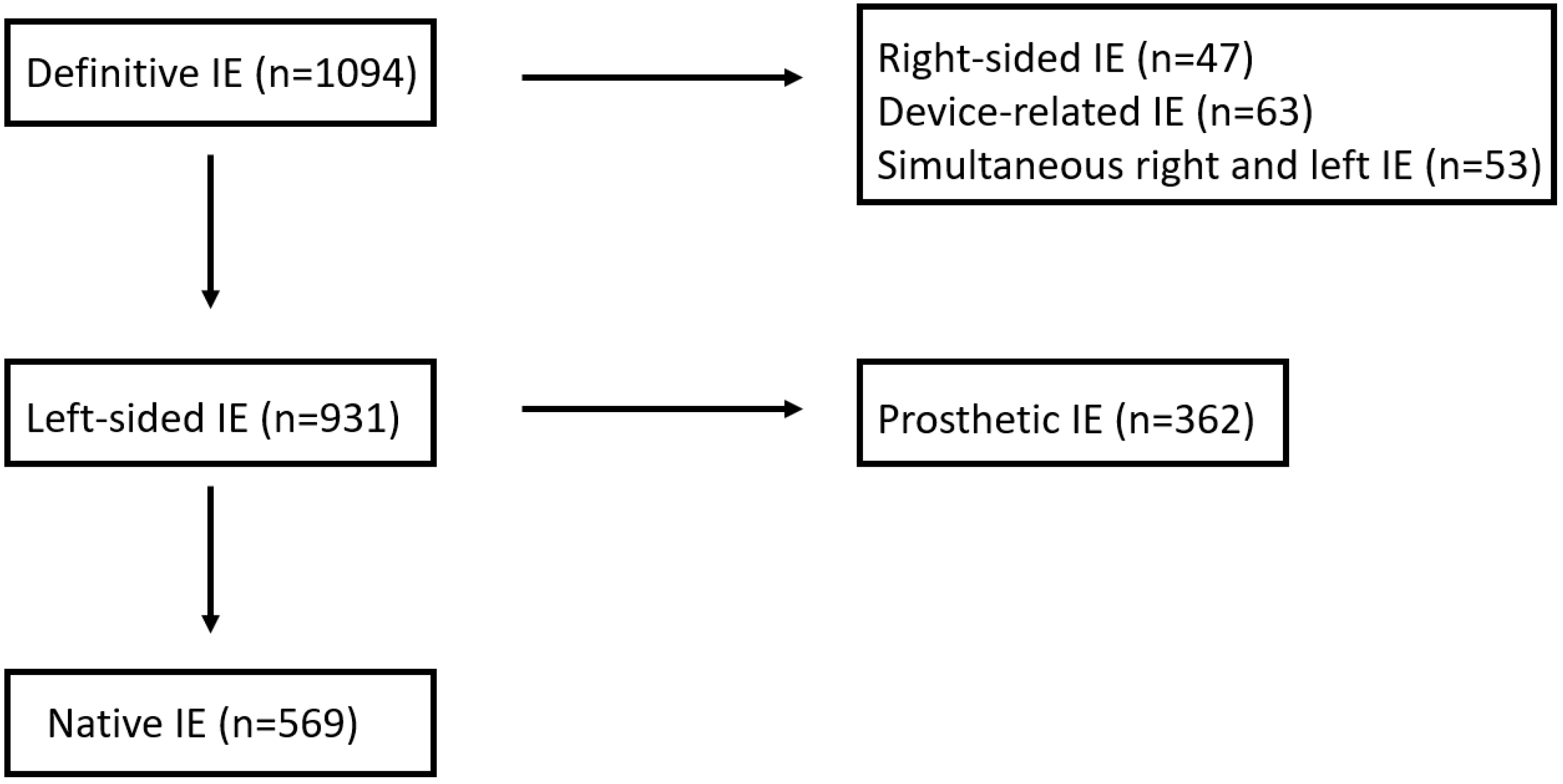

2.1. Patient Population

2.2. Definition of Terms

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Microbiological Profile

3.2. Epidemiological Profile (Table 2)

| Total (n = 569) | S. aureus (n = 120) (a) | S. viridans (n = 112) (b) | Co-n Staph. (n = 56) (c) | Enterococci (n = 76) (d) | Unidentified (n = 45) (e) | p-Value | Post Hoc Comparison | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 66 ± 15 | 67 ± 13 | 59 ± 18 | 71 ± 11 | 71 ± 11 | 63 ± 15 | <0.001 | ab, bc, bd |

| Age > 70 years, n (%) | 261 (46) | 59 (49) | 35 (31) | 36 (64) | 41 (54) | 18 (40) | <0.001 | ab, bc, bd |

| Males, n (%) | 388 (68%) | 76 (63) | 79 (71) | 39 (70) | 57 (75) | 33 (73) | 0.463 | |

| Referred, n (%) | 302 (53) | 71 (60) | 62 (56) | 29 (52) | 42 (55) | 19 (42) | 0.370 | |

| Nosocomial, n (%) | 116 (20) | 42 (35) | 4 (4) | 17 (30) | 20 (26) | 11 (24) | <0.001 | ab, bc, bd, be |

| Acute onset, n (%) | 274 (48) | 98 (82) | 22 (20) | 29 (52) | 29 (38) | 22 (49) | <0.001 | ab, ac, ad, bc, ae, bd, be |

| Days between first symptom and admission | 32 [5–40] | 5 [2–10] | 30 [15–70] | 15 [7–30] | 21 [5–60] | 12 [7–35] | <0.001 | ab, ac, ad, ae |

| Antibiotics 15 days before admission, n (%) | 152 (27) | 34 (31) | 29 (22) | 20 (39) | 15 (21) | 19 (48) | 0.041 | de |

| Possible port of entry of the infection | ||||||||

| Unknown, n (%) | 298 (52) | 55 (46) | 60 (54) | 27 (48) | 36 (47) | 28 (62) | 0.360 | |

| Dental manipulation, n (%) | 47 (8) | 1 (1) | 26 (23) | 1 (2) | 2 (3) | 4 (9) | <0.001 | ab, bc, bd |

| Gastrointestinal manipulation, n (%) | 27 (5) | 3 (3) | 2 (2) | 3 (5) | 5 (7) | 0 (0) | 0.193 | |

| Genitourinary manipulation, n (%) | 24 (4) | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 16 (21) | 0 (0) | <0.001 | ad, bd, cd, de |

| Intravascular catheters, n (%) | 77 (14) | 33 (28) | 2 (2) | 20 (36) | 2 (3) | 5 (11) | <0.001 | ab, ad, bc, cd, ce |

| Skin and soft tissue infections, n (%) | 77 (14) | 24 (20) | 14 (13) | 5 (9) | 9 (12) | 4 (9) | 0.175 | |

| Comorbid conditions | ||||||||

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 154 (27) | 39 (33) | 17 (15) | 17 (30) | 25 (33) | 6 (13) | 0.003 | ab, bd |

| Cancer, n (%) | 79 (14) | 11 (9) | 11 (10) | 11 (20) | 15 (20) | 9 (20) | 0.064 | |

| Immunocomprimised state, n (%) | 47 (8) | 13 (11) | 5 (5) | 5 (9) | 8 (10) | 8 (18) | 0.124 | |

| Alcoholism, n (%) | 57 (10) | 9 (8) | 12 (11) | 3 (5) | 7 (9) | 7 (16) | 0.427 | |

| Chronic renal failure, n (%) | 68 (16) | 27 (23) | 7 (6) | 14 (25) | 11 (15) | 9 (20) | 0.004 | ab, bc |

| Hemodyalisis | 21(3.7) | 7(7) | 2(2) | 5(10.4) | 2(3.1) | 4(10.5) | 0.123 | |

| Colagenopathy, n (%) | 15 (3) | 5 (4) | 0 (0) | 2 (4) | 1 (1) | 3 (7) | 0.110 | |

| Chronic anemia, n (%) | 129 (23) | 25 (21) | 17 (15) | 24 (43) | 22 (29) | 12 (27) | 0.002 | ac, bc |

| COPD | 49(8.6) | 6(5) | 2(1.8) | 10(17.9) | 10(13.2) | 2(4.4) | 0.001 | bc, bd |

| Previous cardiopathy | ||||||||

| No cardiopathy, n (%) | 288 (51) | 65 (57) | 52 (48) | 18 (33) | 37 (51) | 26 (58) | 0.056 | |

| Rheumatic, n (%) | 45 (8) | 10 (8) | 7 (6) | 7 (13) | 6 (8) | 3 (7) | 0.715 | |

| Degenerative, n (%) | 184 (32) | 33 (28) | 28 (25) | 26 (46) | 32 (42) | 12 (27) | 0.011 | bc |

| Congenital, n (%) | 40 (7) | 7 (6) | 15 (13) | 3 (5) | 1 (1) | 7 (16) | 0.008 | bd, de |

| Myxoid, n (%) | 37 (7) | 3 (3) | 14 (13) | 2 (4) | 4 (5) | 3 (7) | 0.027 | ab |

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, n (%) | 14 (3) | 3 (3) | 1 (1) | 4 (7) | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 0.151 | |

| Previous endocarditis, n (%) | 12 (2) | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 2 (4) | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 0.129 | |

| IDUs, n (%) | 8 (1) | 2 (2) | 3 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 0.785 | |

| HIV, n (%) | 8 (1) | 3 (3) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 0.624 | |

3.3. Modes of Presentation (Table 3)

| Total (n = 569) | S. aureus (n = 120) (a) | S. viridans (n = 112) (b) | Co-n Staph. (n = 56) (c) | Enterococci (n = 76) (d) | Unidentified (n = 45) (e) | p-Value | Post Hoc Comparison | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiac, n (%) | 214 (38) | 36 (30) | 32 (29) | 30 (54) | 37 (49) | 25 (56) | <0.001 | ac, ae, bc, bd, be |

| Wasting syndrome, n (%) | 180 (32) | 17 (14) | 54 (49) | 15 (27) | 26 (34) | 14 (31) | <0.001 | ab, ad |

| Neurologic, n (%) | 109 (19) | 34 (28) | 15 (13) | 8 (14) | 6 (8) | 11 (24) | 0.002 | ab, ad |

| Rheumatic, n (%) | 47 (8) | 13 (11) | 10 (9) | 5 (9) | 5 (7) | 0 (0) | 0.226 | |

| Pulmonary, n (%) | 44 (8) | 5 (4) | 5 (5) | 5 (9) | 6 (8) | 5 (11) | 0.375 | |

| Renal, n (%) | 48 (8) | 19 (16) | 8 (7) | 2 (4) | 6 (8) | 4 (9) | 0.063 | |

| Digestive, n (%) | 46 (8) | 9 (8) | 9 (8) | 3 (5) | 5 (7) | 4 (9) | 0.959 | |

| Cutaneous, n (%) | 34 (6) | 13 (11) | 9 (8) | 0 (0) | 2 (3) | 1 (2) | 0.019 |

3.4. Clinical Characteristics at Admission (Table 4)

| Total (n = 569) | S. aureus (n = 120) (a) | S. viridans (n = 112) (b) | Co-n Staph. (n = 56) (c) | Enterococci (n = 76) (d) | Negative (n = 45) (e) | p-Value | Post Hoc Comparison | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fever, n (%) | 383 (67) | 81 (69) | 88 (79) | 30 (54) | 49 (65) | 32 (73) | 0.014 | bc |

| Dyspnea, n (%) | 205 (36) | 36 (30) | 30 (27) | 28 (50) | 33 (44) | 24 (55) | 0.001 | ae, bc, be |

| Meningitis, n (%) | 10 (2) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (4) | 0.140 | |

| Hemoptysis, n (%) | 3 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 0.088 | |

| Chest pain, n (%) | 45 (8) | 3 (3) | 9 (8) | 5 (9) | 8 (11) | 5 (11) | 0.170 | |

| Shivering, n (%) | 226 (40) | 44 (40) | 53 (48) | 23 (41) | 27 (36) | 16 (36) | 0.428 | |

| Confusional syndrome | 66 (12) | 24 (20) | 9 (8) | 3 (5) | 4 (5) | 8 (18) | 0.003 | ab, ad |

| Abdominal pain, n (%) | 52 (9) | 13 (11) | 10 (9) | 6 (11) | 7 (9) | 4 (9) | 0.983 | |

| Mialgia, n (%) | 50 (8) | 9 (8) | 11 (10) | 4 (7) | 6 (8) | 2 (4) | 0.848 | |

| Arthritis/spondylodiscitis, n (%) | 46 (8) | 13(11) | 9(8) | 5(9) | 4(5) | 0 (0) | 0.180 | |

| Cough, n (%) | 56 (10) | 3 (3) | 16 (14) | 4 (7) | 6 (8) | 8 (18) | 0.006 | ab, ae |

| Nausea, n (%) | 39 (7) | 9 (8) | 5 (5) | 4 (7) | 5 (7) | 2 (4) | 0.864 | |

| Headache, n (%) | 31 (5) | 2 (2) | 7 (6) | 4 (7) | 3 (4) | 4 (9) | 0.251 | |

| Stroke, n (%) | 77 (14) | 23 (19) | 7 (6) | 5 (9) | 6 (8) | 11 (24) | 0.002 | ab, be |

| Ischemic, n (%) | 60 (78) | 17 (74) | 5 (71) | 5 (100) | 6 (100) | 9 (82) | 0.446 | |

| Hemorrhagic, n (%) | 17 (22) | 6 (26) | 2 (29) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (18) | ||

| Splenomegaly, n (%) | 38 (7) | 3 (3) | 13 (12) | 1 (2) | 3 (4) | 2 (5) | 0.015 | ab |

| Cutaneous lesions, n (%) | 51 (9) | 21 (18) | 10 (9) | 1 (2) | 4 (5) | 7 (16) | 0.006 | ac |

| Osler nodes, n (%) | 11 (1.9) | 7 (33) | 2 (20) | 0 (0) | 1 (25) | 0 (0) | 0.428 | |

| Janeway lesions, n (%) | 18 (3.2) | 11 (53) | 3 (30) | 0 (0) | 1 (25) | 3 (43) | 0.539 | |

| Splinter hemorrhages, n (%) | 33 (5.8) | 16 (76) | 4 (40) | 0 (0) | 4 (100) | 6 (86) | 0.029 | |

| New murmur, n (%) | 253 (45) | 34 (30) | 59 (53) | 27 (48) | 45 (59) | 19 (43) | <0.001 | ab, ad |

| Acute heart failure, n (%) | 211 (37) | 38 (32) | 26 (23) | 30 (54) | 37 (49) | 23 (51) | <0.001 | ac, bc, bd, be |

| Septic shock | 44 (8) | 25 (21) | 3 (3) | 0 (0) | 3 (3) | 3 (7) | <0.001 | ab, ac, ad |

| Perivalvular complication, n (%) | 146 (26) | 28 (23) | 39 (35) | 20 (36) | 19 (25) | 14 (31) | 0.234 |

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thuny, F.; Grisoli, D.; Collart, F.; Habib, G.; Raoult, D. Management of infective endocarditis: Challenges and perspectives. Lancet 2012, 379, 965–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahill, T.J.; Baddour, L.M.; Habib, G.; Hoen, B.; Salaun, E.; Pettersson, G.B.; Schäfers, H.J.; Prendergast, B.D. Challenges in Infective Endocarditis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017, 69, 325–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, G.; Erba, P.A.; Iung, B.; Donal, E.; Cosyns, B.; Laroche, C.; Popescu, B.A.; Prendergast, B.; Tornos, P.; Sadeghpour, A.; et al. EURO-ENDO Investigators. Clinical presentation, aetiology and outcome of infective endocarditis. Results of the ESC-EORP EURO-ENDO (European infective endocarditis) registry: A prospective cohort study. Eur. Heart J. 2019, 40, 3222–3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermans, P.E. The clinical manifestations of infective endocarditis. Mayo Clin. Proc. 1982, 57, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Hidalgo, N.; Tornos, P. Epidemiology of infective endocarditis in Spain in the last 20 years. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2013, 66, 728–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambrosioni, J.; The Hospital Clinic Infective Endocarditis Investigators; Hernandez-Meneses, M.; Téllez, A.; Pericàs, J.; Falces, C.; Tolosana, J.; Vidal, B.; Almela, M.; Quintana, E.; et al. The Changing Epidemiology of Infective Endocarditis in the Twenty-First Century. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2017, 19, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sevilla, T.; López, J.; Gómez, I.; Vilacosta, I.; Sarriá, C.; García-Granja, P.E.; Olmos, C.; Di Stefano, S.; Maroto, L.; San Román, J.A. Evolution of prognosis in left-sided infective endocarditis: A propensity score analysis of 2 decades. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017, 69, 111–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, L.L.; Otto, C.M. Infective Endocarditis: Update on Epidemiology, Outcomes, and Management. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2018, 20, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.S.; Sexton, D.J.; Mick, N.; Nettles, R.; Fowler, V.G., Jr.; Ryan, T.; Bashore, T.; Corey, G.R. Proposed modifications to the Duke criteria for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2000, 30, 633–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, P.A.; Castelli, W.P.; McNamara, P.M.; Kannel, W.B. The natural history of congestive heart failure: The Framingham study. N. Engl. J. Med. 1971, 285, 1441–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, J.; Revilla, A.; Vilacosta, I.; Sevilla, T.; Villacorta, E.; Sarriá, C.; Pozo, E.; Rollán, M.J.; Gómez, I.; Mota, P.; et al. Age-dependent profile of left-sided infective endocarditis: A 3-center experience. Circulation 2010, 121, 892–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graupner, C.; Vilacosta, I.; SanRomán, J.; Ronderos, R.; Sarriá, C.; Fernández, C.; Mújica, R.; Sanz, O.; Sanmartín, J.V.; Pinto, A.G. Periannular extension of infective endocarditis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2002, 39, 1204–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahl, A.; Bruun, N.E. Enterococcus faecalis infective endocarditis: Focus on clinical aspects. Expert. Rev. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2013, 11, 1247–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Hidalgo, N.; Almirante, B.; Tornos, P.; Pigrau, C.; Sambola, A.; Igual, A.; Pahissa, A. Contemporary epidemiology and prognosis of health care-associated infective endocarditis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008, 47, 1287–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, V.H.; Woods, C.W.; Miro, J.M.; Hoen, B.; Cabell, C.H.; Pappas, P.A.; Federspiel, J.; Athan, E.; Stryjewski, M.E.; Nacinovich, F.; et al. Emergence of coagulase-negative staphylococci as a cause of native valve endocarditis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008, 46, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoerr, V.; Franz, M.; Pletz, M.; Diab, M.; Niemann, S.; Faber, C.; Doenst, T.; Schulze, P.; Deinhardt-Emmer, S.; Löffler, B.S. aureus endocarditis: Clinical aspects and experimental approaches. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2018, 308, 640–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galar, A.; Weil, A.A.; Dudzinski, D.M.; Muñoz, P.; Siedner, M.J. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Prosthetic Valve Endocarditis: Pathophysiology, Epidemiology, Clinical Presentation, Diagnosis, and Management. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2019, 32, e00041-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, J.C.; Anguita, M.P.; Ruiz, M.; Peña, L.; Santisteban, M.; Puentes, M.; Arizón, J.M.; de Lezo, J.S. Changing epidemiology of native valve infective endocarditis. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2011, 64, 594–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, L.; Remadi, J.-P.; Habib, G.; Salaun, E.; Casalta, J.-P.; Tribouilloy, C. Long-term prognosis of left-sided native-valve Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis. Arch. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2016, 109, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakhundi, S.; Zhang, K. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Molecular Characterization, Evolution, and Epidemiology. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2018, 31, e00020-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdoch, D.R.; Corey, G.R.; Hoen, B.; Miró, J.M.; Fowler, V.G.; Bayer, A.S.; Karchmer, A.W.; Olaison, L.; Pappas, P.A.; Moreillon, P.; et al. Clinical presentation, etiology, and outcome of infective endocarditis in the 21st century: The International Collaboration on Endocarditis-Prospective Cohort Study. Arch. Intern. Med. 2009, 169, 463–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mode of Presentation | Signs and Symptoms |

|---|---|

| Cardiac | Acute heart failure, new heart murmur, atrioventricular block |

| Wasting syndrome | Weight loss, asthenia, anorexia |

| Neurologic | Stroke (ischemic or hemorrhagic), confusional syndrome, meningeal syndrome |

| Rheumatic | Arthralgia, myalgia, arthritis, spondylitis |

| Pulmonary | Pneumonia, cough, pulmonary embolism, hemoptysis |

| Renal | Renal failure, proteinuria, hematuria, flank pain |

| Digestive | Abdominal pain |

| Cutaneous | Osler nodes, Janeway lesions, splinter hemorrhages, petechiae |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cabezón, G.; de Miguel, M.; López, J.; Vilacosta, I.; Pulido, P.; Olmos, C.; Jerónimo, A.; Pérez, J.B.; Lozano, A.; Gómez, I.; et al. Contemporary Clinical Profile of Left-Sided Native Valve Infective Endocarditis: Influence of the Causative Microorganism. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5441. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12175441

Cabezón G, de Miguel M, López J, Vilacosta I, Pulido P, Olmos C, Jerónimo A, Pérez JB, Lozano A, Gómez I, et al. Contemporary Clinical Profile of Left-Sided Native Valve Infective Endocarditis: Influence of the Causative Microorganism. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(17):5441. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12175441

Chicago/Turabian StyleCabezón, Gonzalo, María de Miguel, Javier López, Isidre Vilacosta, Paloma Pulido, Carmen Olmos, Adrián Jerónimo, Javier B. Pérez, Adrián Lozano, Itzíar Gómez, and et al. 2023. "Contemporary Clinical Profile of Left-Sided Native Valve Infective Endocarditis: Influence of the Causative Microorganism" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 17: 5441. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12175441

APA StyleCabezón, G., de Miguel, M., López, J., Vilacosta, I., Pulido, P., Olmos, C., Jerónimo, A., Pérez, J. B., Lozano, A., Gómez, I., & San Román, J. A. (2023). Contemporary Clinical Profile of Left-Sided Native Valve Infective Endocarditis: Influence of the Causative Microorganism. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(17), 5441. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12175441