Is Pain Perception Communicated through Mothers? Maternal Pain Catastrophizing Scores Are Associated with Children’s Postoperative Circumcision Pain

Abstract

:1. Introduction

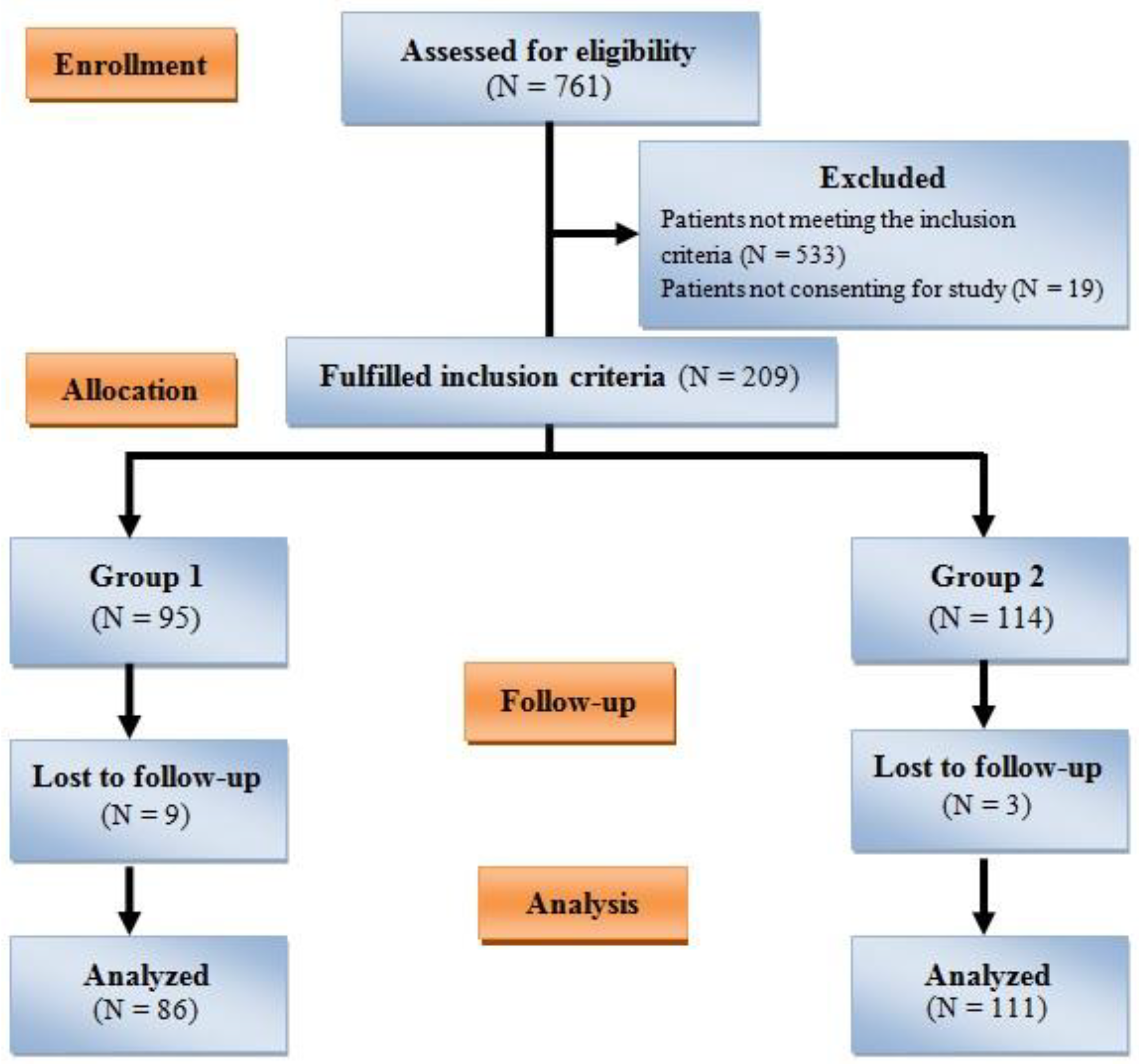

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.1.1. Inclusion Criteria

- -

- Age 5–12 years, and

- -

- Being operated on under general anesthesia.

2.1.2. Exclusion Criteria

- -

- Children attending without their biological mothers or with a parent other than the mother,

- -

- Children aged under five or over 12,

- -

- History of previous surgery,

- -

- Being operated under regional anesthesia,

- -

- Use of analgesic, antiepileptic, or sedative medications, and

- -

- Other procedures are being performed in addition to circumcision (such as herniorrhaphy, tonsillectomy, orchiopexy, and appendectomy).

2.2. The Procedure

2.2.1. Pain Catastrophizing Scale

2.2.2. Beck Depression Inventory

2.3. Evaluation of Postoperative Pain in Children

2.3.1. Visual Analog Scale

2.3.2. Faces Pain Scale

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Karos, K. The Enduring Mystery of Pain in a Social Context. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 66, 524–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palermo, T.M.; Chambers, C.T. Parent and family factors in pediatric chronic pain and disability: An integrative approach. Pain 2005, 119, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goubert, L.; Craig, K.D.; Vervoort, T.; Morley, S.; Sullivan, M.J.L.; Williams, C.A.C.; Cano, A.; Crombez, G. Facing others in pain: The effects of empathy. Pain 2005, 118, 285–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, S.; Tsao, J.C.; Lu, Q.; Myers, C.; Suresh, J.; Zeltzer, L.K. Parent-Child Pain Relationships from a Psychosocial Perspective: A Review of the Literature. J. Pain Manag. 2008, 1, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vervoort, T.; Craig, K.D.; Goubert, L.; Dehoorne, J.; Joos, R.; Matthys, D.; Buysse, A.; Crombez, G. Expressive dimensions of pain catastrophizing: A comparative analysis of school children and children with clinical pain. Pain 2008, 134, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, S.; Keenan, T.R. Parents with chronic pain: Are children equally affected by fathers as mothers in pain? A pilot study. J. Child. Health Care 2007, 11, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Damme, S.; Crombez, G.; Bijttebier, P.; Goubert, L.; Van Houdenhove, B. A confirmatory factor analysis of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale: Invariant factor structure across clinical and non-clinical populations. Pain 2002, 96, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, M.J.; Thorn, B.; Haythornthwaite, J.A.; Keefe, F.; Martin, M.; Bradley, L.A.; Lefebvre, J.C. Theoretical perspectives on the relation between catastrophizing and pain. Clin. J. Pain 2001, 17, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thastum, M.; Zachariae, R.; Herlin, T. Pain experience and pain coping strategies in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J. Rheumatol. 2001, 28, 1091–1098. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, M.J.L.; Bishop, S.R. The pain catastrophizing scale: Development and validation. Psychol. Assess. 1995, 7, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suren, M.; Kaya, Z.; Gokbakan, M.; Okan, I.; Arici, S.; Karaman, S.; Comlekci, M.; Balta, M.G.; Dogru, S. The role of pain catastrophizing score in the prediction of venipuncture pain severity. Pain Pract. 2014, 14, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, A.T.; Steer, R.A.; Brown, G.K. Manual for Beck Depression Inventory-II; Psychological Corporation: San Antonio, TX, USA, 1996; pp. 490–498. [Google Scholar]

- Manworren, R.C.; Stinson, J. Pediatric Pain Measurement, Assessment, and Evaluation. Semin. Pediatr. Neurol. 2016, 23, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boerner, K.E.; Chambers, C.T.; McGrath, P.J.; LoLordo, V.; Uher, R. The Effect of Parental Modeling on Child Pain Responses: The Role of Parent and Child Sex. J. Pain 2017, 18, 702–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, J.E.; McGrath, P.J. Mothers’ modeling influences children’s pain during a cold pressor task. Pain 2003, 104, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muris, P.; Steerneman, P.; Merckelbach, H.; Meesters, C. The role of parental fearfulness and modeling in children’s fear. Behav. Res. Ther. 1996, 34, 265–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraljevic, S.; Banozic, A.; Maric, A.; Cosic, A.; Sapunar, D.; Puljak, L. Parents’ pain catastrophizing is related to pain catastrophizing of their adult children. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2012, 19, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, S.; Meldrum, M.; Tsao, J.C.; Fraynt, R.; Zeltzer, L.K. Associations between parent and child pain and functioning in a pediatric chronic pain sample: A mixed methods approach. Int. J. Disabil. Hum. Dev. 2010, 9, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagé, M.G.; Campbell, F.; Isaac, L.; Stinson, J.; Katz, J. Parental risk factors for the development of pediatric acute and chronic postsurgical pain: A longitudinal study. J. Pain Res. 2013, 6, 727–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteve, R.; Marquina-Aponte, V.; Ramírez-Maestre, C. Postoperative pain in children: Association between anxiety sensitivity, pain catastrophizing, and female caregivers’ responses to children’s pain. J. Pain 2014, 15, 157–168.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristiansen, F.L.; Olesen, A.E.; Brock, C.; Gazerani, P.; Petrini, L.; Mogil, J.S.; Drewes, A.M. The role of pain catastrophizing in experimental pain perception. Pain Pract. 2014, 14, E136–E145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forstenpointner, J.; Ruscheweyh, R.; Attal, N.; Baron, R.; Bouhassira, D.; Enax-Krumova, E.K.; Finnerup, N.B.; Freynhagen, R.; Gierthmühlen, J.; Hansson, P.; et al. No pain, still gain (of function): The relation between sensory profiles and the presence or absence of self-reported pain in a large multicenter cohort of patients with neuropathy. Pain 2021, 162, 718–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzan, O.K.; Sahin, O.O.; Baran, O. Effect of Puppet Show on Children’s anxiety and pain levels during the circumcision operation: A randomized controlled trial. J. Pediatr. Urol. 2020, 16, 490.e1–490.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyuk, E.T.; Odabasoglu, E.; Uzsen, H.; Koyun, M. The effect of virtual reality on Children’s anxiety, fear, and pain levels before circumcision. J. Pediatr. Urol. 2021, 17, 567.e1–567.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zavras, N.; Tsamoudaki, S.; Ntomi, V.; Yiannopoulos, I.; Christianakis, E.; Pikoulis, E. Predictive Factors of Postoperative Pain and Postoperative Anxiety in Children Undergoing Elective Circumcision: A Prospective Cohort Study. Korean J. Pain 2015, 28, 244–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polat, F.; Tuncel, A.; Balci, M.; Aslan, Y.; Sacan, O.; Kisa, C.; Kayali, M.; Atan, A. Comparison of local anesthetic effects of lidocaine versus tramadol and effect of child anxiety on pain level in circumcision procedure. J. Pediatr. Urol. 2013, 9, 670–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connelly, M.; Fulmer, R.D.; Prohaska, J.; Anson, L.; Dryer, L.; Thomas, V.; Ariagno, J.E.; Price, N.; Schwend, R. Predictors of postoperative pain trajectories in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine 2014, 39, E174–E181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabbitts, J.A.; Zhou, C.; Groenewald, C.B.; Durkin, L.; Palermo, T.M. Trajectories of postsurgical pain in children: Risk factors and impact of late pain recovery on long-term health outcomes after major surgery. Pain 2015, 156, 2383–2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.G.; Stinson, J.; Campbell, F.; Isaac, L.; Katz, J. Identification of pain-related psychological risk factors for the development and maintenance of pediatric chronic postsurgical pain. J. Pain Res. 2013, 6, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breau, L.M.; Camfield, C.S.; McGrath, P.J.; Finley, G.A. The incidence of pain in children with severe cognitive impairments. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2003, 157, 1219–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malviya, S.; Voepel-Lewis, T.; Tait, A.R.; Merkel, S.; Lauer, A.; Munro, H.; Farley, F. Pain management in children with and without cognitive impairment following spine fusion surgery. Paediatr. Anaesth. 2001, 11, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, J.L.; Fanurik, D.; Harrison, R.D.; Schmitz, M.L.; Norvell, D. Analgesia following surgery in children with and without cognitive impairment. Pain 2004, 111, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascella, M.; Bimonte, S.; Saettini, F.; Muzio, M.R. The challenge of pain assessment in children with cognitive disabilities: Features and clinical applicability of different observational tools. J. Paediatr. Child. Health. 2019, 55, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myles, P.S.; Williams, D.L.; Hendrata, M.; Anderson, H.; Weeks, A.M. Patient satisfaction after anaesthesia and surgery: Results of a prospective survey of 10,811 patients. Br. J. Anaesth. 2000, 84, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chazapis, M.; Walker, E.M.K.; Rooms, M.A.; Kamming, D.; Moonesinghe, S.R. Measuring quality of recovery-15 after day case surgery. Br. J. Anaesth. 2016, 116, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wessels, E.; Perrie, H.; Scribante, J.; Jooma, Z. Quality of recovery in the perioperative setting: A narrative review. J. Clin. Anesth. 2022, 78, 110685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, U.; Simsek, F.; Kamburoglu, H.; Ozhan, M.O.; Alakus, U.; Ince, M.E.; Eksert, S.; Ozkan, G.; Eskin, M.B.; Senkal, S. Linguistic validation of a widely used recovery score: Quality of recovery-15 (QoR-15). Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2022, 46, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Group 1 (N = 86) | Group 2 (N = 111) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years, mean ± SD) | 35.09 ± 6.09 | 35.7 ± 5.62 | 0.468 |

| PCS-TR score (mean ± SD) | 8.26 ± 4.94 | 27.84 ± 8.64 | <0.001 |

| Education (N, %) Primary High school University | 20 (23.2%) 43 (50%) 23 (26.8%) | 54 (48.7%) 36 (32.4%) 21 (18.9%) | 0.004 |

| Employment (N, %) Housewife Service sector Nurse Teacher Officer | 59 (68.6%) 13 (15.1%) 5 (5.8%) 5 (5.8%) 4 (4.7%) | 84 (75.7%) 20 (18%) 2 (1.8%) 4 (3.6%) 1 (0.9%) | 0.289 |

| Marital status (N, %) Married Divorced | 83 (96.5%) 3 (3.5%) | 107 (96.4%) 4 (3.6%) | 0.965 |

| Number of children (mean ± SD) | 2.22 ± 0.7 | 2.03 ± 0.72 | 0.075 |

| Presence of chronic disease (N, %) | 14 (16.3%) | 20 (18%) | 0.496 |

| Presence of chronic pain (N, %) | 29 (33.7%) | 58 (52.3%) | 0.009 |

| VAS of chronic pain | 3.03 ± 1.37 | 3.98 ± 1.44 | 0.004 |

| Beck Depression Inventory score * | 6 (3–10) | 12 (7–18) | <0.001 |

| Variables | Group 1 (N = 86) | Group 2 (N = 111) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years, mean ± SD) | 6.88 ± 1.3 | 6.82 ± 1.26 | 0.766 |

| Education (N, %) Nursery Kindergarten Primary school | 12 (14%) 19 (22.1%) 55 (62.9%) | 11 (9.9%) 29 (26.1%) 71 (64%) | 0.837 |

| Presence of chronic disease (N, %) | 9 (10.5%) | 17 (15.3%) | 0.594 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Akdeniz, S.; Pece, A.H.; Kusderci, H.S.; Dogru, S.; Tulgar, S.; Suren, M.; Okan, I. Is Pain Perception Communicated through Mothers? Maternal Pain Catastrophizing Scores Are Associated with Children’s Postoperative Circumcision Pain. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6187. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12196187

Akdeniz S, Pece AH, Kusderci HS, Dogru S, Tulgar S, Suren M, Okan I. Is Pain Perception Communicated through Mothers? Maternal Pain Catastrophizing Scores Are Associated with Children’s Postoperative Circumcision Pain. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(19):6187. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12196187

Chicago/Turabian StyleAkdeniz, Sevda, Ahmet Haydar Pece, Hatice Selcuk Kusderci, Serkan Dogru, Serkan Tulgar, Mustafa Suren, and Ismail Okan. 2023. "Is Pain Perception Communicated through Mothers? Maternal Pain Catastrophizing Scores Are Associated with Children’s Postoperative Circumcision Pain" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 19: 6187. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12196187