Understanding the Association between Red Blood Cell Transfusion Utilization and Humanistic and Economic Burden in Patients with β-Thalassemia from the Patients’ Perspective

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Data Source

2.2. Study Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Study Assessments

2.3.1. Demographic Characteristics and Treatment History

2.3.2. HRQoL Outcomes

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)

Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7)

Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Anemia (FACT-An)

Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI)

2.3.3. Time Burden

2.3.4. Treatment Burden

2.3.5. Burden of ICT and Comorbidities

2.3.6. Direct and Indirect Costs

2.3.7. Employment and Health Insurance

2.3.8. Caregiver Burden

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics and Treatment History

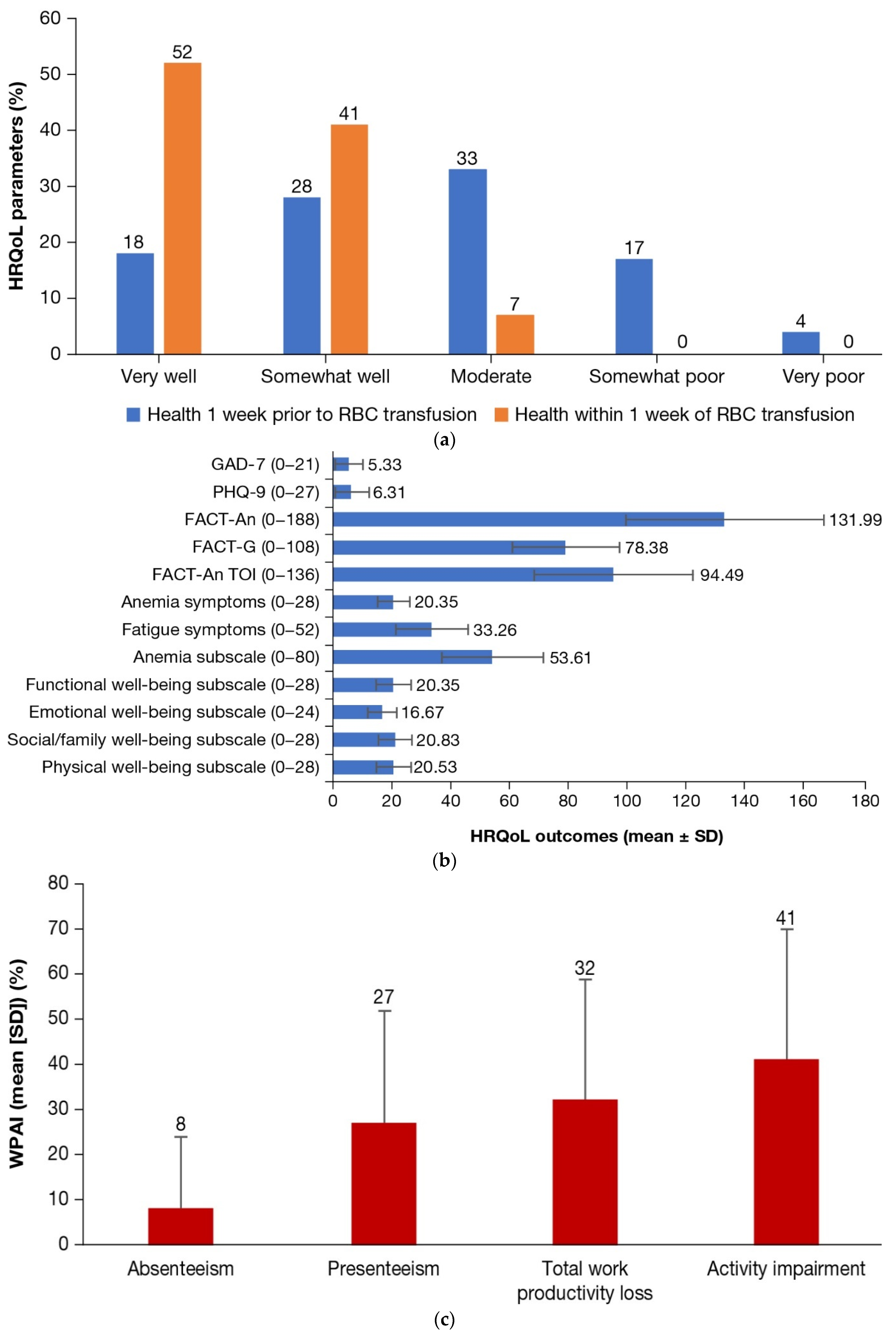

3.2. HRQoL Outcomes

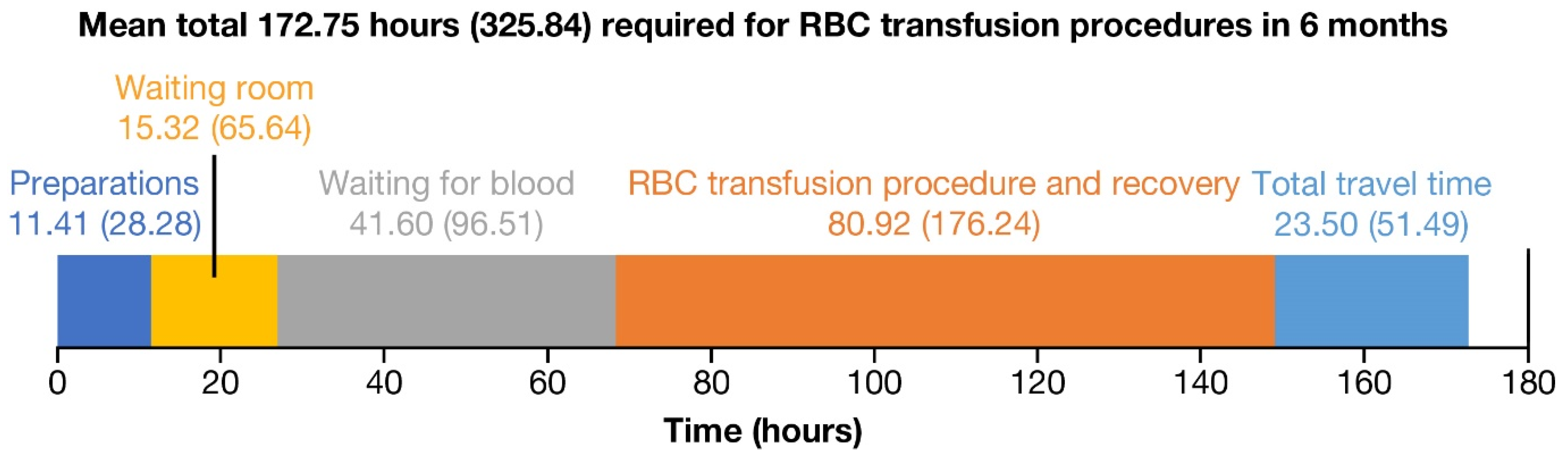

3.3. Time Burden

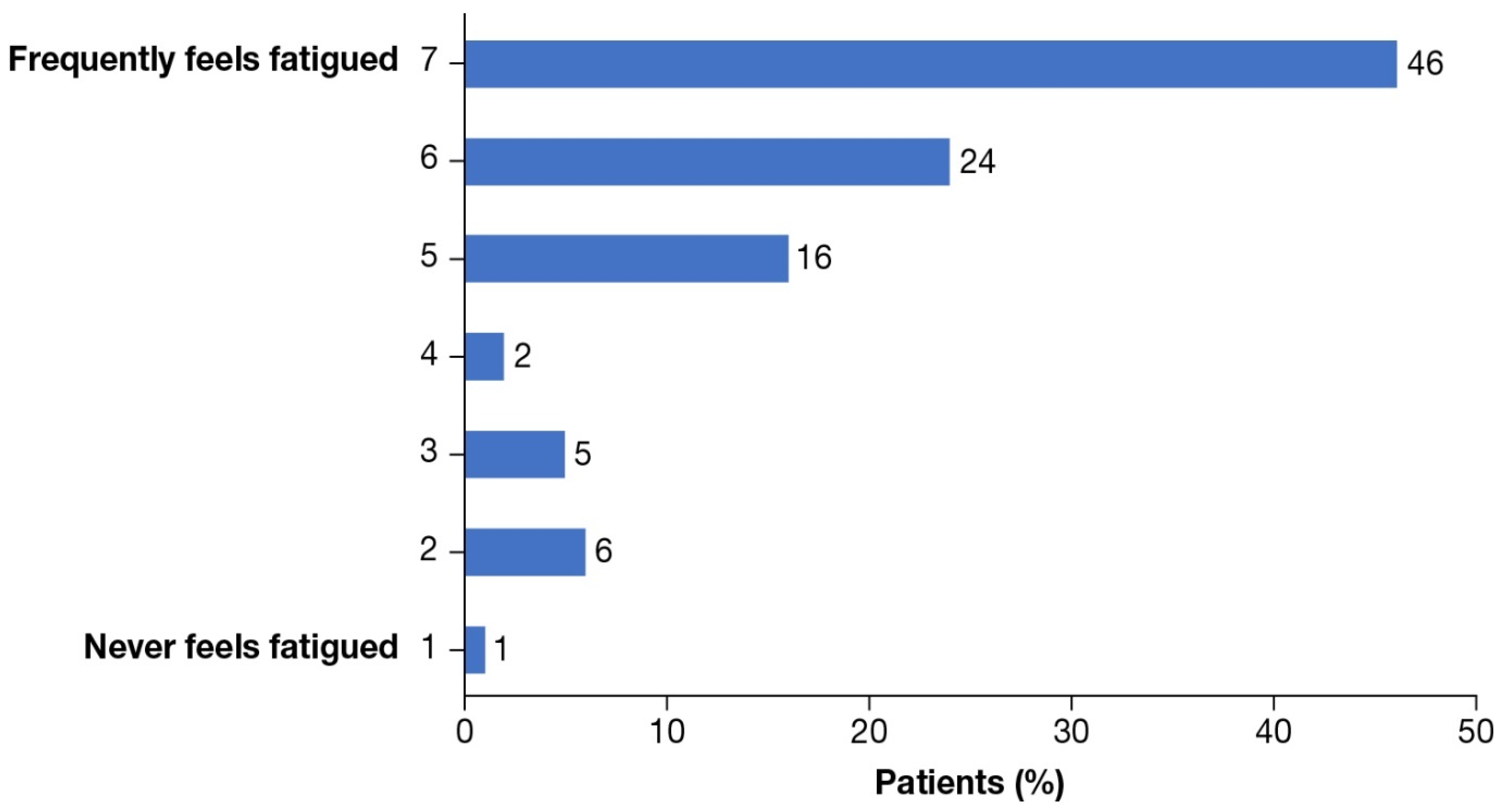

3.4. Treatment Burden

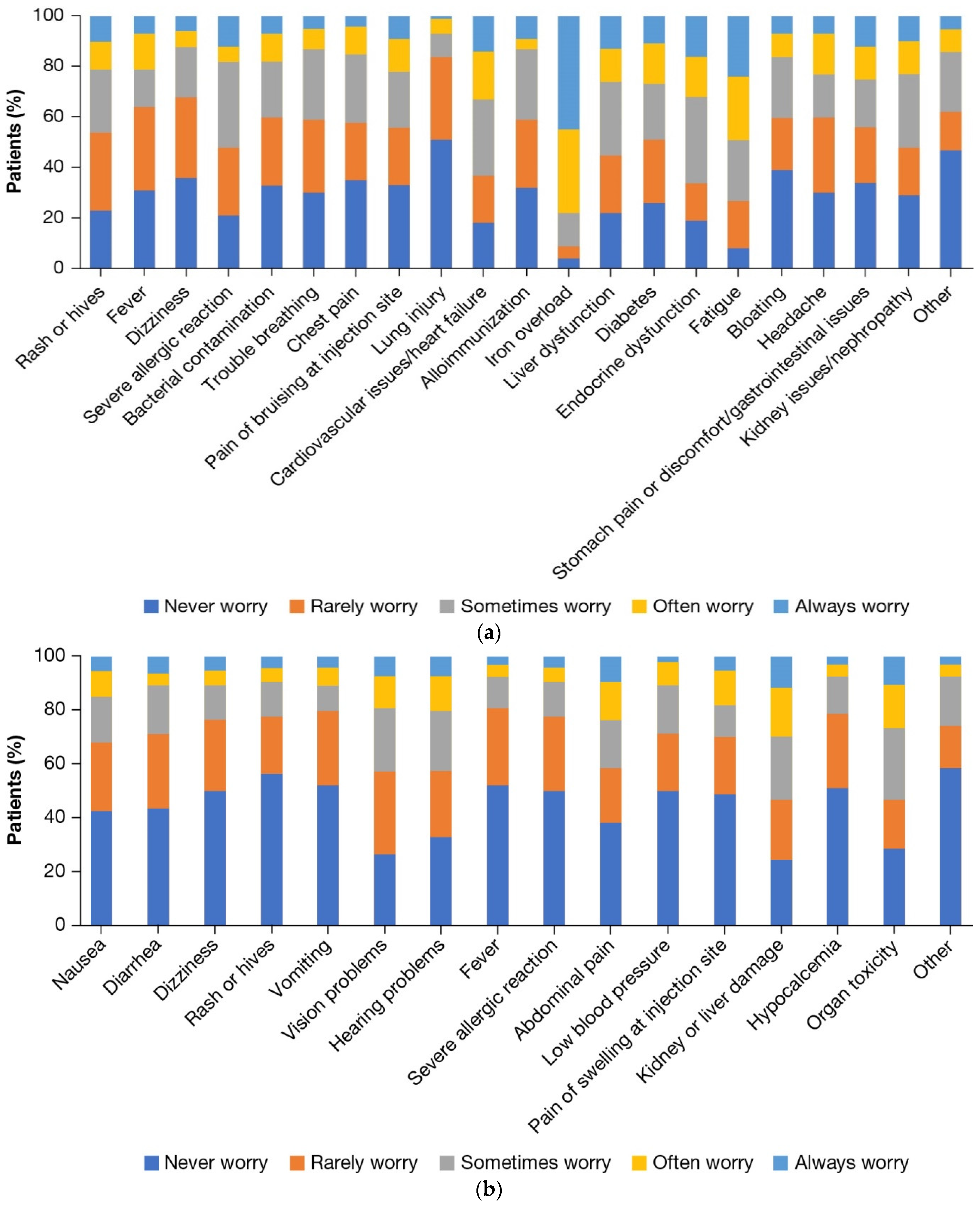

3.5. Burden of ICT and Comorbidities

3.6. Direct and Indirect Costs

3.7. Employment and Health Insurance

3.8. Caregiver Burden

4. Discussion

Strength and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Galanello, R.; Origa, R. Beta-thalassemia. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2010, 5, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). Rare Disease Database; Beta Thalassemia. Available online: https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/thalassemia-major/ (accessed on 24 August 2022).

- Sayani, F.A.; Kwiatkowski, J.L. Increasing prevalence of thalassemia in America: Implications for primary care. Ann. Med. 2015, 47, 592–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United States Census Bureau. How Do We Know? America’s Foreign Born in the Last 50 Years. Available online: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/sis/resources/visualizations/foreign-born.html (accessed on 24 August 2022).

- MedlinePlus. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine; Beta Thalassemia. Available online: https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/condition/beta-thalassemia/ (accessed on 24 August 2022).

- Porter, J.; Viprakasit, V.; Kattamis, A. Iron overload and chelation. In Guidelines for the Management of Transfusion Dependent Thalassaemia (TDT), 3rd ed.; Cappellini, M.D., Cohen, A., Porter, J., Taher, A., Viprakasit, V., Eds.; Thalassaemia International Federation: Nicosia, Cyprus, 2014. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK269382/ (accessed on 24 August 2022).

- Yengil, E.; Acipayam, C.; Kokacya, M.H.; Kurhan, F.; Oktay, G.; Ozer, C. Anxiety, depression and quality of life in patients with beta thalassemia major and their caregivers. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2014, 7, 2165–2172. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4161562/ (accessed on 24 August 2022).

- Trachtenberg, F.; Foote, D.; Martin, M.; Carson, S.; Coates, T.; Beams, O.; Vega, O.; Merelles-Pulcini, M.; Giardina, P.J.; Kleinert, D.A.; et al. Pain as an emergent issue in thalassemia. Am. J. Hematol. 2010, 85, 367–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betts, M.; Flight, P.A.; Paramore, L.C.; Tan, L.; Milenković, D.; Sheth, S. Systematic literature review of the burden of disease and treatment for transfusion-dependent β-thalassemia. Clin. Ther. 2020, 42, 322–337.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cappellini, M.D.; Kattamis, A.; Viprakasit, V.; Sutcharitchan, P.; Pariseau, J.; Laadem, A.; Jessent-Ciaravino, V.; Taher, A. Quality of life in patients with β-thalassemia: A prospective study of transfusion-dependent and non-transfusion-dependent patients in Greece, Italy, Lebanon, and Thailand. Am. J. Hematol. 2019, 94, E261–E264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sobota, A.; Yamashita, R.; Xu, Y.; Trachtenberg, F.; Kohlbry, P.; Kleinert, D.A.; Giardina, P.J.; Kwiatkowski, J.L.; Foote, D.; Thayalasuthan, V.; et al. Quality of life in thalassemia: A comparison of SF-36 results from the thalassemia longitudinal cohort to reported literature and the US norms. Am. J. Hematol. 2011, 86, 92–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Trachtenberg, F.L.; Gerstenberger, E.; Xu, Y.; Mednick, L.; Sobota, A.; Ware, H.; Thompson, A.A.; Neufeld, E.J.; Yamashita, R. Thalassemia clinical research network. Relationship among chelator adherence, change in chelators, and quality of life in thalassemia. Qual. Life Res. 2014, 23, 2277–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thuret, I.; Hacini, M.; Pégourié-Bandelier, B.; Gardembas-Pain, M.; Bisot-Locard, S.; Merlat-Guitard, A.; Bachir, D. Socio-psychological impact of infused iron chelation therapy with deferoxamine in metropolitan France: ISOSFER study results. Hematology 2009, 14, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidhu, S.; Kakkar, S.; Dewan, P.; Bansal, N.; Sobti, P.C. Adherence to iron chelation therapy and its determinants. Int. J. Hematol. Oncol. Stem Cell Res. 2021, 15, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, S.; Weiss, M.; Parisi, M.; Ni, Q. Clinical and economic burden of transfusion-dependent β-thalassemia in adult patients in the United States. Blood 2017, 130, 2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, F.T.; Sayani, F.; Trompeter, S.; Drasar, E.; Piga, A. Challenges of blood transfusions in β-thalassemia. Blood Rev. 2019, 37, 100588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manea, L.; Gilbody, S.; McMillan, D. Optimal cut-off score for diagnosing depression with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9): A meta-analysis. CMAJ 2012, 184, E191–E196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.W.; Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cella, D. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Anemia (FACT-An) Scale: A new tool for the assessment of outcomes in cancer anemia and fatigue. Semin. Hematol. 1997, 34, 13–19. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9253779/ (accessed on 24 August 2022).

- FACIT.org. Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy—Fatigue. Available online: https://www.facit.org/measures/FACIT-F (accessed on 24 August 2022).

- Reilly, M.C.; Zbrozek, A.S.; Dukes, E.M. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics 1993, 4, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlson, M.E.; Pompei, P.; Ales, K.L.; MacKenzie, C.R. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J. Chronic Dis. 1987, 40, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikael, N.A.; Al-Allawi, N.A. Factors affecting quality of life in children and adolescents with thalassemia in Iraqi Kurdistan. Saudi Med. J. 2018, 39, 799–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuysuz, G.; Tayfun, F. Health-related quality of life and its predictors among transfusion-dependent thalassemia patients. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2017, 39, 332–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messina, G.; Colombo, E.; Cassinerio, E.; Ferri, F.; Curti, R.; Altamura, C.; Cappellini, M.D. Psychosocial aspects and psychiatric disorders in young adult with thalassemia major. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2008, 3, 339–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arian, M.; Mirmohammadkhani, M.; Ghorbani, R.; Soleimani, M. Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in beta-thalassemia major (β-TM) patients assessed by 36-item short form health survey (SF-36): A meta-analysis. Qual. Life Res. 2019, 28, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mevada, S.T.; Al Saadoon, M.; Zachariah, M.; Al Rawas, A.H.; Wali, Y. Impact of burden of thalassemia major on health-related quality of life in Omani children. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2016, 38, 384–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheri, M.; Rohban, A.; Sadeghi, R.; Joveini, H. Predictors of quality of life in transfusion-dependent thalassemia patients based on the PRECEDE model: A structural equation modeling approach. J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2020, 10, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paramore, C.; Levine, L.; Bagshaw, E.; Ouyang, C.; Kudlac, A.; Larkin, M. Patient- and caregiver-reported burden of transfusion-dependent β-thalassemia measured using a digital application. Patient 2021, 14, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jowsey, T.; Yen, L.; Mathews, W.P. Time spent on health related activities associated with chronic illness: A scoping literature review. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grangé, S.; Bertrand, D.M.; Guerrot, D.; Eas, F.; Godin, M. Acute renal failure and Fanconi syndrome due to deferasirox. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2010, 25, 2376–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cappellini, M.D.; Porter, J.; El-Beshlawy, A.; Li, C.-K.; Seymour, J.F.; Elalfy, M.; Gattermann, N.; Giraudier, S.; Lee, J.-W.; Chan, L.L.; et al. Tailoring iron chelation by iron intake and serum ferritin: The prospective EPIC study of deferasirox in 1744 patients with transfusion-dependent anemias. Haematologica 2010, 95, 557–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Riewpaiboon, A.; Nuchprayoon, I.; Torcharus, K.; Indaratna, K.; Thavorncharoensap, M.; Ubol, B.-O. Economic burden of beta-thalassemia/Hb E and beta-thalassemia major in Thai children. BMC Res. Notes 2010, 3, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Raju, B.; Reddy, K. Are counseling services necessary for the surgical patients and their family members during hospitalization? J. Neurosci. Rural Pract. 2017, 8, 114–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Committee on Family Caregiving for Older Adults; Board on Health Care Services; Health and Medicine Division; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Family Caregiving Roles and Impacts. In Families Caring for an Aging America; Schulz, R., Eden, J., Eds.; National Academies Press (US): Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Yellen, S.B.; Cella, D.F.; Webster, K.; Blendowski, C.; Kaplan, E. Measuring fatigue and other anemia-related symptoms with the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) measurement system. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 1997, 13, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Overall, N = 100 |

|---|---|

| Age [mean ± SD], years | 35.99 ± 10.36 |

| Female, n (%) | 65 (65) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 42 (42) |

| White | 34 (34) |

| Hispanic | 14 (14) |

| Mixed race | 2 (2) |

| Other | 7 (7) |

| Declined to answer | 1 (1) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |

| Single, never married | 49 (49) |

| Married/living with partner | 46 (46) |

| Separated/divorced | 5 (5) |

| Household income, n (%) | |

| USD < 15,000–24,999 | 27 (27) |

| USD 25,000–49,999 | 12 (12) |

| USD 50,000–99,999 | 15 (15) |

| USD ≥ 100,000 | 33 (33) |

| Declined to answer | 13 (13) |

| Education, n (%) | |

| <High school graduate or equivalent (e.g., GED) to completed some school/college, but no degree | 17 (17) |

| Associate degree/college graduate (e.g., B.A., B.S.)/completed some graduate school, but no degree | 55 (55) |

| Completed graduate school (e.g., M.S., M.D., Ph.D.) | 27 (27) |

| Declined to answer | 1 (1) |

| Currently has health insurance, n (%) | 98 (98) |

| Insurance type, n (%) a | N = 98 |

| Managed Care (HMO, PPO) | 56 (57.1) |

| Medicaid (MediCal for California residents)/Medicare | 46 (47) |

| High deductible health plan with HSA—also called “Consumer Directed Plan” | 5 (5.1) |

| Other | 11 (11.2) |

| Health insurance covers prescription medications, n (%) | 89 (90.8) |

| Time since diagnosis [mean ± SD], years | 34.40 ± 10.33 |

| Prior treatment received for β-thalassemia, n (%) | |

| RBC transfusion | 100 (100) |

| ICT | 94 (94) |

| Surgery | 47 (47) |

| Stem cell/bone marrow transplant | 5 (5) |

| Other | 3 (3) |

| Number of transfusions received in the past 6 months [mean ± SD] | 9.62 ± 4.32 |

| Frequency of transfusions, n (%) | |

| >1 per month | 66 (66) |

| Monthly | 31 (31) |

| Every other month | 3 (3) |

| Time since last RBC transfusion, n (%) | |

| ≤1 week | 38 (38) |

| 8–14 days | 32 (32) |

| 15–30 days | 27 (27) |

| >1 month–4 months | 3 (3) |

| RBC transfusion burden, n (%) | |

| Extremely high burden | 14 (14) |

| High burden | 20 (20) |

| Moderate burden | 36 (36) |

| Some burden | 21 (21) |

| No burden | 9 (9) |

| Psychological burden Rating of β-thalassemia treatment routine (1—treatment has become routine, 7—treatment is a huge burden), n (%) | |

| 1 | 41 (41) |

| 2 | 24 (24) |

| 3 | 10 (10) |

| 4 | 9 (9) |

| 5 | 6 (6) |

| 6 | 5 (5) |

| 7 | 5 (5) |

| Office visits, n (%) | 92 (92) |

| Turned away for blood transfusion due to shortage, n (%) | 10 (10) |

| Laboratory/blood test visits, n (%) | 83 (83) |

| ER visits, n (%) | 7 (7) |

| Hospitalizations, n (%) | 3 (3) |

| Employed, n (%) | 63 (63) |

| Employment decision affected by β-thalassemia, n (%) | 52 (82.5) |

| How employment choice was affected by β-thalassemia, n (%) a | |

| Chose for health insurance plan | 37 (58.7) |

| Provided flexible hours | 37 (58.7) |

| Provided needed job security | 33 (52.4) |

| Not too physical | 26 (41.3) |

| Close to a treatment center | 18 (28.6) |

| Other reason | 2 (3.2) |

| HRQoL Parameters | Overall, N = 100 |

|---|---|

| Depression symptom severity, n (%) | |

| None/minimal | 48 (48) |

| Mild | 24 (24) |

| Moderate | 18 (18) |

| Moderately severe | 7 (7) |

| Severe | 3 (3) |

| Anxiety symptom severity, n (%) | |

| None/minimal | 47 (47) |

| Mild | 36 (36) |

| Moderate | 12 (12) |

| Severe | 5 (5) |

| Overall, N = 100 (Mean ± SD) | |

|---|---|

| Number of HCPs seen for whole transfusion process (1 appointment) | 5.11 ± 3.97 |

| Number of follow-up visits in past 6 months (all patients) | |

| Treating HCPs | 9.40 ± 8.16 |

| Office visits | 3.92 ± 3.75 |

| Laboratory/blood test visits | 6.09 ± 4.92 |

| ER visits | 0.10 ± 0.46 |

| Hospitalizations | 0.03 ± 0.17 |

| Total time spent in the past 6 months, among patients reporting visits | |

| All office visits, hours (n = 92) | 3.99 ± 5.41 |

| All laboratory/blood test visits, hours (n = 83) | 3.21 ± 2.85 |

| All ER visits, hours (n = 7) | 5.93 ± 3.45 |

| Hospitalizations, days (n = 3) | 2.17 ± 1.15 |

| For treatment (e.g., scheduling, billing issues, insurance issues, etc.), hours | 8.51 ± 11.41 |

| Time spent in the past 6 months, hours | |

| Preparing for transfusion (i.e., getting blood drawn) | 11.41 ± 28.28 |

| Waiting for blood to arrive | 41.60 ± 96.51 |

| Waiting in the waiting room prior to the transfusion | 15.32 ± 65.64 |

| Getting the transfusion (being prepared and recovering) | 80.92 ± 176.24 |

| Traveling to and from the transfusion location | 23.50 ± 51.49 |

| Scheduling appointments | 2.69 ± 2.84 |

| Getting insurance verification | 1.44 ± 2.97 |

| Calling about billing issues | 3.09 ± 5.40 |

| Getting a/working with social worker | 1.29 ± 3.79 |

| Overall, N = 100 | |

|---|---|

| Expenses outside of care, n (%) | |

| Childcare | 9 (9) |

| Transportation | 72 (72) |

| Parking/tolls | 54 (54) |

| Prescription medication(s) | 59 (59) |

| OTC (non-prescription) medication(s) | 48 (48) |

| Other | 8 (8) |

| Burden related to insurance issues, n (%) | |

| Extremely high burden | 11 (11) |

| High burden | 28 (28) |

| Moderate burden | 15 (15) |

| Some burden | 22 (22) |

| No burden | 24 (24) |

| Costs in the past 6 months, USD | (N = 100) |

| Total OOPC related to care, among patients reporting visits, [mean ± SD], USD | 896.15 ± 3066.84 |

| Office visits (n = 92) | 555.23 ± 1981.87 |

| ER visits (n = 7) | 143.00 ± 153.76 |

| Hospitalizations (n = 3) | 41.67 ± 52.04 |

| Laboratory visits/blood tests (n = 83) | 450.70 ± 1531.11 |

| Amount of money spent for blood transfusion, [mean ± SD] | 2239.18 ± 5537.33 |

| Total costs outside of care, among patients reporting costs, [mean ± SD], USD | 962.34 ± 2457.98 |

| Childcare (n = 9) | 1780.00 ± 2778.69 |

| Transportation (n = 72) | 178.83 ± 177.64 |

| Parking/tolls (n = 54) | 111.00 ± 131.50 |

| Prescription medication(s) (n = 59) | 791.59 ± 2501.01 |

| OTC (non-prescription) medication(s) (n = 48) | 157.5 ± 192.06 |

| Other (n = 8) | 885.00 ± 1584.53 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Knoth, R.L.; Gupta, S.; Perkowski, K.; Costantino, H.; Inyart, B.; Ashka, L.; Clapp, K. Understanding the Association between Red Blood Cell Transfusion Utilization and Humanistic and Economic Burden in Patients with β-Thalassemia from the Patients’ Perspective. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 414. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12020414

Knoth RL, Gupta S, Perkowski K, Costantino H, Inyart B, Ashka L, Clapp K. Understanding the Association between Red Blood Cell Transfusion Utilization and Humanistic and Economic Burden in Patients with β-Thalassemia from the Patients’ Perspective. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(2):414. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12020414

Chicago/Turabian StyleKnoth, Russell L., Shaloo Gupta, Kacper Perkowski, Halley Costantino, Brian Inyart, Lauren Ashka, and Kelly Clapp. 2023. "Understanding the Association between Red Blood Cell Transfusion Utilization and Humanistic and Economic Burden in Patients with β-Thalassemia from the Patients’ Perspective" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 2: 414. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12020414

APA StyleKnoth, R. L., Gupta, S., Perkowski, K., Costantino, H., Inyart, B., Ashka, L., & Clapp, K. (2023). Understanding the Association between Red Blood Cell Transfusion Utilization and Humanistic and Economic Burden in Patients with β-Thalassemia from the Patients’ Perspective. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(2), 414. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12020414