Caregivers of Neuromuscular Patients Living with Tracheostomy during COVID-19 Pandemic: Their Experience

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Objectives

3. Methods

Ethics

4. Study Design and Methodological Orientation

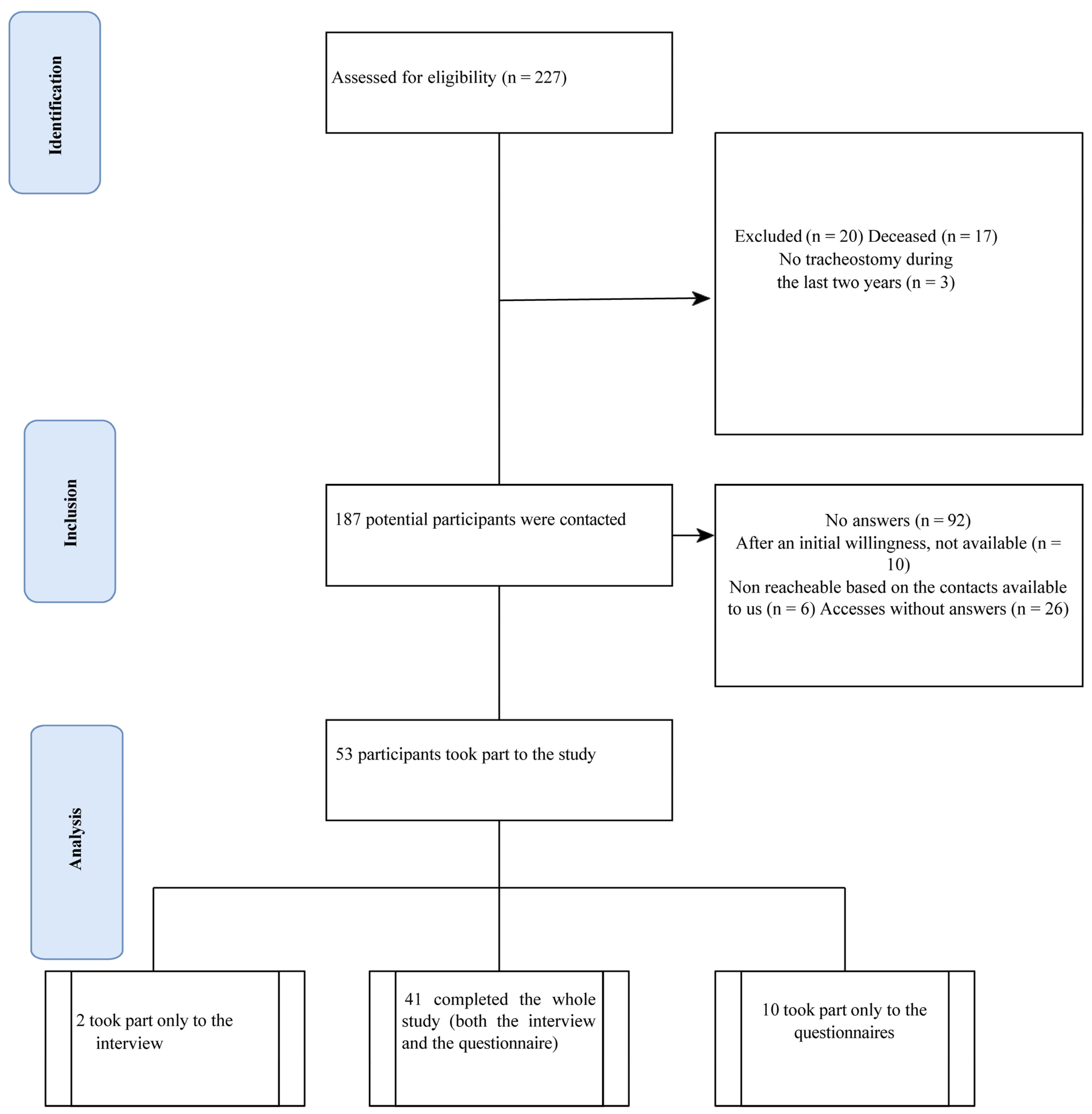

5. Participants

5.1. Sampling

5.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

5.3. Setting and Time

5.4. Materials and Data Collection

- -

- Socio-demographic and clinical data: gender, level of education, profession (current or previous), marital status, role, how long they have been caring for their loved one and for how many hours/weeks, drug therapy taken, pathologies and/or comorbidities (if any).

- -

- Psychological tests:

- (a)

- Connor and Davidson’s Resilience Scale (CD-RISC-25) [24], designed to detect resilience. The CD-RISC consists of five factors: 1. personal competence and tenacity (8 items); 2. self-confidence and management of negative emotions (7 items); 3. positive acceptance of change and secure relationships (5 items); 4. control (3 items); 5. spiritual influences (2 items). The Connor Davidson-Resilience Scale is based on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 “totally false” to 5 “totally true”. The Resilience Scale has good internal consistency with values of Cronbach’s alpha varying across research from a minimum of 0.82 to a maximum of 0.93. Its stability was also measured using the retest method at 24 weeks with equally positive results.

- (b)

- Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II (AAQ-II) [25], designed to detect flexibility. The AAQ-II was developed to establish an internally consistent measure of the mental health and behavioral effectiveness model of ACT. The AAQ-II began as a 10-item scale, but after the final psychometric analysis it was reduced to a 7-item scale (2011). It was designed to assess the same construct as the AAQ-I and the two scales are correlated at 0.97, but the AAQ-II has better psychometric consistency.

- (c)

- State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) [26], designed to detect trait anxiety. The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) is a psychological questionnaire based on a 4-point Likert scale and consists of 40 questions on a self-report basis. The ST,AI measures two types of anxiety—state anxiety, or anxiety about an event and trait anxiety, or level of anxiety as a personal characteristic. Higher scores are positively correlated with higher levels of anxiety. Its most recent revision is Form Y and is offered in 40 languages. The internal consistency coefficients for the scale ranged from 0.86 to 0.95; test–retest reliability coefficients ranged from 0.65 to 0.75 over a range of 2 months. The test–retest coefficients for this measure in the present study ranged from 0.69 to 0.89. This offers considerable evidence of the scale’s construct and concurrent validity.

- (d)

- Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI) [27], designed to detect caregiver burden. The Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI) is a 22-question questionnaire designed to measure the extent to which a caregiver perceives his or her level of burden because of caring for a person with a particular diagnosis. Initially developed to measure the stress associated with caring for elderly people living in the community, it has since been validated in many patient populations and is a common measure of caregiver burden. Based on the original 29-item scale, the ZBI has undergone several modifications that have led to the current 22-item assessment. The ZBI questions comprise 5 domains: (1) burden in the relationship (6 items), (2) emotional well-being (7 items), (3) social and family life (4 items), (4) finances (1 item) and (5) loss of control over one’s life (4 items). Most items explore both personal stress (12 items) and role stress (6 items). The ZBI uses a 4-point ordinal scale describing the degree of load experienced from 0 = never to 4 = almost always and takes about 10 min to complete. The maximum score is 88 with higher scores indicating a greater load.

- (e)

- Langer Mindfulness Scale (LMS) [28], to measure dispositional mindfulness. This is a questionnaire with 21 questions to be used as a training, self-discovery and research tool. It assesses four domains associated with mindfulness thinking: novelty seeking, engagement, novelty production and flexibility. An individual who seeks novelty perceives every situation as an opportunity to learn something new. An individual who scores high in engagement is likely to notice more details about his or her specific relationship with the environment. An individual who produces novelty generates new information to learn more about the current situation. Flexible people welcome a changing environment rather than resist it. The LMS has proven to have good test–retest reliability, factor validity and construct validity.

5.5. Data Management

5.6. Data Analysis

6. Results

6.1. Participant Demographics

6.2. The Tracheostomy Experience through the Caregivers’ Eye

6.3. Caregivers Confronted with Tracheostomy at the Time of the Pandemic: Semi-Structured Interviews

6.4. Perceived Changes

6.5. Coping Strategies

6.6. Emotions

6.7. Relationships

6.8. Satisfaction

6.9. Tracheo’s Changes

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALS | Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis |

| SMA | Spinal Muscular Atrophy |

| DMD | Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy |

| COPD | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| COREQ | Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research Checklist |

| IPA | Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis |

| CD-RISC-25 | Connor and Davidson’s Resilience Scale |

| AAQ-II | Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II |

| STAI | State-Trait Anxiety Inventory |

| ZBI | Zarit Burden Interview |

| LMS | Langer Mindfulness Scale |

| NMD | Neuro muscular Disease |

References

- Luo, F.; Djillali, A.; Orlikowski, D.; He, L.; Yang, M.; Zhou, M.; Guan, J.L. Invasive versus non-invasive ventilation for acute respiratory failure in neuromuscular disease and chest wall disorders. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 12, CD008380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanum, T.; Zia, S.; Khan, T.; Kamal, S.; Khoso, M.N.; Alvi, J.; Ali, A. Assessment of knowledge regarding tracheostomy care and management of early complications among healthcare professionals. Braz J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2022, 88, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakarada-Kordic, I.; Patterson, N.; Wrapson, J.; Reay, S.D. A Systematic Review of Patient and Caregiver Experiences with a Tracheostomy. Patient Cent. Outcomes Res. 2018, 11, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman-Sanderson, A.L.; Togher, L.; Elkins, M.; Kenny, B. Quality of life improves for tracheostomy patients with return of voice: A mixed methods evaluation of the patient experience across the care continuum. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2018, 46, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stan, D.; Tuta, M.-D.; Tatu, A.L. Psychosocial Implications of Patients with Tracheostomy—A Suggestive Example of Interdisciplinarity. Brain 2021, 12, 308–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerogianni, G.; Lianos, E.; Kouzoupis, A.; Polikandrioti, M.; Grapsa, E. The role of socio-demographic factors in depression and anxiety of patients on hemodialysis: An observational cross-sectional study. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2018, 50, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, L.; Rosenberg, M.W.; Zeng, J. Changing caregiving relationships for older home-based Chinese people in a transitional stage: Trends, factors and policy implications. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2017, 70, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, P.-Y.; Wang, H.-P.; Chang, T.-H.; Yu, J.-M.; Lee, S.-Y. Stress, stress-related symptoms and social support among Taiwanese primary family caregivers in intensive care units. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2018, 49, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Seo, J. Analysis of caregiver burden in palliative care: An integrated review. Nurs. Forum 2019, 54, 280–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fumis, R.R.L.; Junqueira Amarante, G.A.; de Fátima Nascimento, A.; Vieira Junior, J.M. Moral distress and its contribution to the development of burnout syndrome among critical care providers. Ann. Intensive Care 2017, 7, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, J.I.; Chu, L.M.; Matte, A.; Tomlinson, G.; Chan, L.; Thomas, C.; Friedrich, J.O.; Mehta, S.; Lamontagne, F.; Levasseur, M.; et al. One-Year Outcomes in Caregivers of Critically Ill Patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 1831–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Born-van Zanten, S.A.; Dongelmans, D.A.; Dettling-Ihnenfeldt, D.; Vink, R.; van der Schaaf, M. Caregiver strain and posttraumatic stress symptoms of informal caregivers of intensive care unit survivors. Rehabil. Psychol. 2016, 61, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, L.D.; Arslanian-Engoren, C. Caring for Survivors of Prolonged Mechanical Ventilation. Home Health Care Manag. Pr. 2002, 14, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yu, J.; Ouyang, W.; Chua, M.L.K.; Xie, C. SARS-CoV-2 Transmission in Patients With Cancer at a Tertiary Care Hospital in Wuhan, China. JAMA Oncol. 2020, 6, 1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Greco, F.; Altieri, V.M.; Esperto, F.; Mirone, V.; Scarpa, R.M. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Health-Related Quality of Life in Uro-oncologic Patients: What Should We Wait For? Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2021, 19, e63–e68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younger, E.; Smrke, A.; Lidington, E.; Farag, S.; Ingley, K.; Chopra, N.; Maleddu, A.; Augustin, Y.; Merry, E.; Wilson, R.; et al. Health-Related Quality of Life and Experiences of Sarcoma Patients during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Cancers 2020, 12, 2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, B.; Dergousoff, J.; Slater, L.; Harris, J.; O’Connell, D.; El-Hakim, H.; Biron, V.L.; Mitchell, N.; Seikaly, H. Depression and Survival in Patients With Head and Neck Cancer. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2016, 142, 284–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musoro, J.Z.; Coens, C.; Singer, S.; Tribius, S.; Oosting, S.F.; Groenvold, M.; Simon, C.; Machiels, J.; Grégoire, V.; Velikova, G.; et al. Minimally important differences for interpreting European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 scores in patients with head and neck cancer. Head Neck 2020, 42, 3141–3152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eatough, V.; Smith, A. Interpretative phenomenological analysis. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 179–195. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.; Flowers, P.; Larkin, M. Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fade, S. Using interpretative phenomenological analysis for public health nutrition and dietetic research: A practical guide. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2004, 63, 647–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, B.; Sim, J.; Kingstone, T.; Baker, S.; Waterfield, J.; Bartlam, B.; Burroughs, H.; Jinks, C. Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 1893–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, K.M.; Davidson, J.R.T. Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress. Anxiety 2003, 18, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, F.W.; Hayes, S.C.; Baer, R.A.; Carpenter, K.M.; Guenole, N.; Orcutt, H.K.; Tom, W.; Robert, D.Z. Preliminary Psychometric Properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire–II: A Revised Measure of Psychological Inflexibility and Experiential Avoidance. Behav. Ther. 2011, 42, 676–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spielberger, C.D. State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Adults (STAI-AD); APA PsycTests: Washington, DC, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bédard, M.; Molloy, D.W.; Squire, L.; Dubois, S.; Lever, J.A.; O’Donnell, M. The Zarit Burden Interview. Gerontologist 2001, 41, 652–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pirson, M.A.; Langer, E. Developing the Langer Mindfulness Scale. Acad. Manag. Proc. 2015, 2015, 11308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krefting, L. Rigor in Qualitative Research: The Assessment of Trustworthiness. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 1991, 45, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipolletta, S.; Amicucci, L. The family experience of living with a person with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A qualitative study. Int. J. Psychol. 2015, 50, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tremolizzo, L.; Pellegrini, A.; Susani, E.; Lunetta, C.; Woolley, S.C.; Ferrarese, C.; Appollonio, I. Behavioural But Not Cognitive Impairment Is a Determinant of Caregiver Burden in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Eur. Neurol. 2016, 75, 191–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bock, M.; Duong, Y.N.; Kim, A.; Allen, I.; Murphy, J.; Lomen-Hoerth, C. Cognitive-behavioral changes in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Screening prevalence and impact on patients and caregivers. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2016, 17, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carretero, S.; Garcés, J.; Ródenas, F.; Sanjosé, V. The informal caregiver’s burden of dependent people: Theory and empirical review. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2009, 49, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chio, A.; Gauthier, A.; Calvo, A.; Ghiglione, P.; Mutani, R. Caregiver burden and patients’ perception of being a burden in ALS. Neurology 2005, 64, 1780–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giusiano, S.; Peotta, L.; Iazzolino, B.; Mastro, E.; Arcari, M.; Palumbo, F. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis caregiver burden and patients’ quality of life during COVID-19 pandemic. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2022, 23, 146–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siciliano, M.; Santangelo, G.; Trojsi, F.; Di Somma, C.; Patrone, M.; Femiano, C. Coping strategies and psychological distress in caregivers of patients with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS). Amyotroph Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2017, 18, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Wit, J.; Beelen, A.; Drossaert, C.H.; Kolijn, R.; Van Den Berg, L.H.; SchrÖder, C.D.; Visser-Meily, J.M. Blended psychosocial support for partners of patients with ALS and PMA: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2020, 21, 344–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharbafshaaer, M.; Buonanno, D.; Passaniti, C.; De Stefano, M.; Esposito, S.; Canale, F. Psychological Support for Family Caregivers of Patients With Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis at the Time of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic: A Pilot Study Using a Telemedicine Approach. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 904841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banfi, P.; Pierucci, P.; Volpato, E.; Nicolini, A.; Lax, A.; Robert, D.; Bach, J. Daytime noninvasive ventilatory support for patients with ventilatory pump failure: A narrative review. Multidiscip. Respir. Med. 2019, 14, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Crimi, C.; Pierucci, P.; Carlucci, A.; Cortegiani, A.; Gregoretti, C. Long-Term Ventilation in Neuromuscular Patients: Review of Concerns, Beliefs, and Ethical Dilemmas. Respiration 2019, 97, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierucci, P.; Portacci, A.; Carpagnano, G.E.; Banfi, P.; Crimi, C.; Misseri, G.; Gregoretti, C. The right interface for the right patient in noninvasive ventilation: A systematic review. Expert Rev. Respir. Med. 2022, 16, 931–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alvano, G.; Buonanno, D.; Passaniti, C.; De Stefano, M.; Lavorgna, L.; Tedeschi, G. Support Needs and Interventions for Family Caregivers of Patients with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS): A Narrative Review with Report of Telemedicine Experiences at the Time of COVID-19 Pandemic. Brain Sci. 2021, 12, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasta, R.; Moglia, C.; D’Ovidio, F.; Di Pede, F.; De Mattei, F.; Cabras, S. Telemedicine for patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis during COVID-19 pandemic: An Italian ALS referral center experience. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2021, 22, 308–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, S.; Quintarelli, S.; Silani, V. New technologies and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis—Which step forward rushed by the COVID-19 pandemic? J. Neurol. Sci. 2020, 418, 117081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Marchi, F.; Sarnelli, M.F.; Serioli, M.; De Marchi, I.; Zani, E.; Bottone, N. Telehealth approach for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients: The experience during COVID-19 pandemic. Acta. Neurol. Scand. 2021, 143, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capozzo, R.; Zoccolella, S.; Musio, M.; Barone, R.; Accogli, M.; Logroscino, G. Telemedicine is a useful tool to deliver care to patients with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis during COVID-19 pandemic: Results from Southern Italy. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2020, 21, 542–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambrosino, N.; Pierucci, P. Using Telemedicine to Monitor the Patient with Chronic Respiratory Failure. Life 2021, 11, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Semi-Structured Interview Question |

|---|

| 1. What do you think has changed in the management of tracheotomy during COVID-19? |

| 2. How is the home care received during the period of the medical emergency? |

| 3. How do you feel/are you feeling about this management? |

| 4. What kind of changes have you noticed in your relationship with home healthcare professionals? |

| 5. What difficulties are you experiencing with the management of the tracheotomy during the health emergency? |

| Possible prompts: When?/How often?/Physical?/Emotional?/Practical? |

| 6. What difficulties are you experiencing with the management of the tracheotomy during the lockdown period? |

| Possible prompts: When?/How often?/Physical?/Emotional?/Practical? |

| 7. What emotions are you predominantly experiencing during the medical emergency period? |

| Possible prompts: Can you think of specific situations? |

| 8. What emotions are you predominantly experiencing during the lockdown period? |

| Possible prompts: Can you think of specific situations? |

| 9. Which metaphor would you used to describe tracheostomy? |

| Variables | Levels | N (%) | M (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N) | 53 (100%) | ||

| Age (M, SD) | 52.2 (18.2) | ||

| Gender (n, %) | Men | 19 (35.8%) | |

| Women | 33 (62.3%) | ||

| Prefer not to say | 1 (1.9%) | ||

| Marital Status (n, %) | Married | 39 (73.6%) | |

| Divorced | 2 (3.8%) | ||

| Separated | 1 (1.9%) | ||

| Single | 5 (9.4%) | ||

| Widower | 2 (3.8%) | ||

| Other | 4 (7.5%) | ||

| Education (n, %) | Primary School | 5 (9.6%) | |

| Secondary School | 9 (17.3%) | ||

| High School | 23 (44.2%) | ||

| Bachelor’s degree | 6 (11.5%) | ||

| Master’s degree | 8 (15.4%) | ||

| Other Specialisations (e.g., PhD) | 1 (1.9%) | ||

| None | 1 (1.9%) | ||

| Kind of job practiced before the diagnoses of the loved ones | Self-employed | 7 (13.20%) | |

| Housewife | 6 (11.32%) | ||

| Teacher | 3 (5.66%) | ||

| Engineer | 3 (5.66%) | ||

| Doctor | 2 (3.77%) | ||

| Business Consultant | 2 (3.77%) | ||

| Employee | 10 (18.86%) | ||

| Retired | 2 (3.77%) | ||

| Other | 18 (33.96%) | ||

| Age of the dear ones M, (SD) | 50.2 (21.2) | ||

| Genderof the dear ones (n,%) | Men | 9 (40.9%) | |

| Women | 11 (50%) | ||

| Prefer not to say | 2 (9.1%) | ||

| Disease of the dear ones | Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) | 18 (33.9%) | |

| Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA) | 4 (7.54%) | ||

| Congenital Myopathies | 1 (1.9%) | ||

| Multiple Sclerosis (MS) | 2 (3.77%) | ||

| Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD) | 1 (1.9%) | ||

| Muscular Dystrophy | 1 (1.9%) | ||

| Encephalopathy | 2 (3.77%) | ||

| Tetra-paresis | 3 (5.66%) | ||

| Other | 21 (39.62%) | ||

| Kind of onset (only in case of ALS) | Bulbar | 6 (33.3%) | |

| Spinal (lower limbs) | 8 (44.4%) | ||

| Spinal (upper limbs) | 2 (11.1%) | ||

| Respiratory | 2 (11.1%) | ||

| Non-Invasive Ventilation (NIV) before tracheostomy | Yes | 22 (41.5%) | |

| No | 14 (26.41%) | ||

| I don’t know | 4 (7.54%) | ||

| No answer | 13 (24.52%) | ||

| Where did you try NIV for the first time? | At the hospital | 19 (35.84%) | |

| Outpatient clinic | 2 (3.77%) | ||

| No answer | 32 (60.37%) | ||

| Problems with NIV | Conjunctivitis, connective or corneal ulcers | 1 (1.88%) | |

| Skin abrasions or ulcerations due to the mask | 6 (11.32%) | ||

| Dry nose and mouth | 2 (3.77%) | ||

| Decubitus | 2 (3.77%) | ||

| Airways obstruction | 2 (3.77%) | ||

| Other | 7 (13.20%) | ||

| No answer | 33 (62.3%) | ||

| Hours of NIV’s usage before tracheostomy | 15.1 (8.11) | ||

| Years of disease | 13.8 (14.4) | ||

| Years from diagnosis | 9.58 (11.5) | ||

| Diagnosis-tracheostomy time (Days) | 4218 (7776) | ||

| Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy (PEG) | Yes | 35 (66.03%) | |

| No | 9 (16.98%) | ||

| No answer | 9 (16.98%) | ||

| Use of cough assistant | Yes | 5 (9.43%) | |

| No | 12 (22.64%) | ||

| I don’t know | 2 (3.77%) | ||

| No answer | 34 (64.15%) | ||

| Phonatory valve during open ventilation | Yes | 10 (18.86%) | |

| No | 30 (56.6%) | ||

| I’ve tried it in the past, but I can’t use it | 3 (5.66%) | ||

| No answer | 10 (18.86%) | ||

| Use O2 or not | Yes | 19 (35.84%) | |

| No | 27 (50.94%) | ||

| No answer | 7 (13.2%) | ||

| How much? | 0.93 (0.90) |

| The Tracheostomy to Your Loved One Was Done | N (%) |

| After extensively discussing it with doctors… | 9 (16.98%) |

| After having extensively discussed it with the Doctors and a Psychologist… | 10 (18.86%) |

| In an emergency, but I knew it could happen | 12 (22.64%) |

| In case of urgency, absolutely unexpected | 13 (24.52%) |

| Other | 2 (3.77%) |

| No answer | 7 (13.20%) |

| Before your loved one received the tracheostomy, you thought that… | |

| His/Her quality of life would have improved | 9 (16.98%) |

| He/She would be able to resume and/or continue my activities of daily living (e.g., at home, with my loved ones, work…) | 6 (11.32%) |

| I feel that he/she has many more years ahead of him/her | 6 (11.32%) |

| He/She can no longer communicate verbally | 6 (11.32%) |

| He/She can no longer eat | 6 (11.32%) |

| Other | 2 (3.77%) |

| No answer | 18 (33.96%) |

| After your loved one received the tracheostomy, it happened that… | |

| My quality of life has been improved | 9 (16.98%) |

| I was able to resume and/or continue to carry out my activities of daily life (e.g., at work, at home, with my dear ones…) | 5 (9.43%) |

| I feel he/she would have many more years ahead of him/her | 9 (16.98%) |

| I cannot longer communicate with him/her | 8 (15.09%) |

| I cannot longer have lunch/dinner with him/her | 8 (15.09%) |

| Other | 3 (5.66%) |

| No answer | 11 (20.75%) |

| Superordinate Themes | Themes | Subthemes |

|---|---|---|

| Changes (43; 100%; 167 references) | Perceived changes in the assistance during the lockdowns (43; 100%; 141 references) | Big differences (18; 41.86%; 35 references) |

| Medium differences (16; 37.20%; 21 references) | ||

| No differences (33; 76.74%; 85 references) | ||

| Perceived changes in the assistance after the lockdowns (19; 44.18%; 26 references) | Confusion (2; 4.65%; 3 references) | |

| Getting Better (4; 9.30%; 4 references) | ||

| Persistence (5; 11.62%; 7 references) | ||

| Restart (8; 18.6%; 12 references) | ||

| Coping Strategies (30; 69.76%; 52 references) | Emotion-focused (14; 32.55%; 26 references) | |

| Passive adaptation (2; 4.65%; 3 references) | ||

| Problem focused (9; 20.93%; 16 references) | ||

| Social support (5; 11.62%; 7 references) | ||

| Emotions (43; 100%; 79 references) | Caregivers’ emotions (43; 100%; 71 references) | Abandoned (19; 44.18%; 33 references) |

| Anger (2; 4.65%; 2 references) | ||

| Anxiety (8; 18.60%; 12 references) | ||

| Distress (1; 2.32; 2 references) | ||

| Fear (12; 27.90%; 21 references) | ||

| Anxiety related to the mass media (1; 2.32%; 1 reference) | ||

| Others’ emotions (6; 13.95%; 8 references) | Frightening (6; 13.95%; 8 references) | |

| Relationships (32; 74.41%; 50 references) | Abandoned (Covid-19 or not) (9; 20.93%; 12 references) | |

| With others, the Health Care Professionals (23; 53.48%; 37 references) | ||

| Satisfaction (5; 11.62%; 5 references) | Bad (1; 2.32%; 1 reference) | |

| Same as before (3; 6.97%; 3 references) | ||

| Getting better (1; 2.32%; 1 reference) | ||

| Tracheo’s changes (17; 39.53%; 37 references) | Emotion related to tracheo’s changes (2; 4.65%; 3 references) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pierucci, P.; Volpato, E.; Grosso, F.; De Candia, M.L.; Casparrini, M.; Compalati, E.; Pagnini, F.; Banfi, P.; Carpagnano, G.E. Caregivers of Neuromuscular Patients Living with Tracheostomy during COVID-19 Pandemic: Their Experience. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 555. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12020555

Pierucci P, Volpato E, Grosso F, De Candia ML, Casparrini M, Compalati E, Pagnini F, Banfi P, Carpagnano GE. Caregivers of Neuromuscular Patients Living with Tracheostomy during COVID-19 Pandemic: Their Experience. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(2):555. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12020555

Chicago/Turabian StylePierucci, Paola, Eleonora Volpato, Francesca Grosso, Maria Luisa De Candia, Massimo Casparrini, Elena Compalati, Francesco Pagnini, Paolo Banfi, and Giovanna Elisiana Carpagnano. 2023. "Caregivers of Neuromuscular Patients Living with Tracheostomy during COVID-19 Pandemic: Their Experience" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 2: 555. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12020555

APA StylePierucci, P., Volpato, E., Grosso, F., De Candia, M. L., Casparrini, M., Compalati, E., Pagnini, F., Banfi, P., & Carpagnano, G. E. (2023). Caregivers of Neuromuscular Patients Living with Tracheostomy during COVID-19 Pandemic: Their Experience. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(2), 555. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12020555