Five-Year Efficacy and Safety of TiNO-Coated Stents Versus Drug-Eluting Stents in Acute Coronary Syndrome: A Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Study Identification and Selection

3.2. Individual Study Characteristics

| Study | Age and Prior Events | Clinical Presentation (Included and Pooled) | Procedural Data and Medication | Lost to Follow-Up | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stent | TiNOS | DES | TiNOS N Incl, % pooled | DES N Incl, % pooled | TiNOS | DES | ||||

| TITAX-AMI DES = PES [24,25] | Patients n age prior MI prior PCI prior CABG | 214 64 ± 11 15% 10% 7% | 211 64 ± 11 9% 5% 6% | STEMI NSTEMI UAP | 83, 39% 131, 61% 0, 0% | 97, 46% 114, 54% 0, 0% | Stents/culprit lesion n TSL (mm) Post-dilation Procedural success DAPT 12 m | 1.1 ± 0.3 18.5 ± 6.4 42% 99.5% 31% | 1.1 ± 0.4 19.2 ± 7.2 35% 98.1% 65% | TiNOS: 3 DES: 7 |

| BASE-ACS DES = EES [26,27] | Patients n age prior MI prior PCI prior CABG | 417 63 ± 12 13.4% 9.6% 4.8% | 410 63 ± 12 9.8% 10.5% 4.1% | STEMI NSTEMI UAP | 162, 38.8% 206, 49.4% 49, 11.8% | 159, 38.8% 187, 45.6% 64, 15.6% | Stents/culprit lesion n TSL (mm) Post-dilation Stent failure DAPT: Aspirin: N.R. Clopidogrel: N.R. | 1.15 ± 0.38 20.8 ± 9.4 42.2% 0.0% | 1.14 ± 0.36 20.6 ± 8.2 43.9% 1.0% | TiNOS: 29 DES: 28 |

| TIDES-ACS DES = EES [23,28] | Patients n age prior MI prior PCI prior CABG | 989 62.7 ± 10.7 6% 7.0% 0.6% | 502 62.6 ± 10.5 9.0% 6.6% 1.2% | STEMI NSTEMI UAP | 444, 44.9% 458, 46.3% 87, 8.8% | 239, 47.6% 226, 45.8% 37, 7.4% | Stents/culprit lesion n TSL (mm) Post-dilation Stent failure DAPT 12 m | 1.13 ± 0.38 20.5 ± 7.8 33.0% 0.3% 80.3% | 1.14 ± 0.37 20.6 ± 7.2 38.0% 1.0% 86.0% | TiNOS: 35 DES: 14 |

3.3. Individual Study Risk of Bias

3.4. Publication Bias Risk

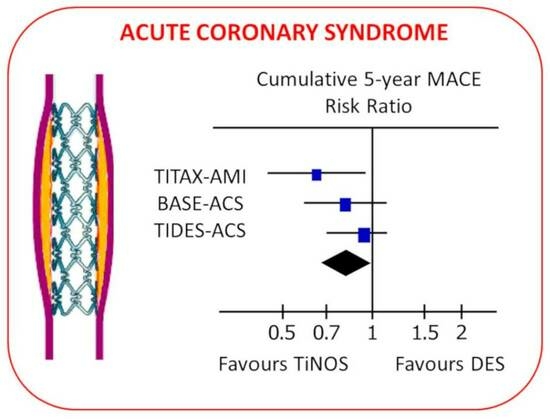

3.5. Pooled Cumulative Outcomes

3.6. Sensitivity Analysis

3.7. GRADE Certainty of Evidence

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of the Results

4.2. Clinical Validity

4.3. Generalization of the Results

4.4. Plaque Destabilization Risk

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Detailed Search Strings in Each Database

Appendix B. Identified References Ineligible for the Meta-Analysis

- Windecker, S.; Simon, R.; Lins, M.; Klauss, V.; Eberli, F.R.; Roffi, M.; Pedrazzini, G.; Moccetti, T.; Wenaweser, P.; Togni, M.; et al. Randomized comparison of a titanium-nitride-oxide-coated stent with a stainless steel stent for coronary revascularization—The TiNOX trial. Circulation 2005, 111, 2617–2622. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.486647.

- Grube, E.; Buellesfeld, L. BioMatrix Biolimus A9-eluting coronary stent: A next-generation drug-eluting stent for coronary artery disease. Expert Rev. Med. Devices 2006, 3, 731–741. https://doi.org/10.1586/17434440.3.6.731.

- Wu, P.; Grainger, D.W. Drug/device combinations for local drug therapies and infection prophylaxis. Biomaterials 2006, 27, 2467.

- Coolong, A.; Kuntz, R.E. Understanding the drug-eluting stent trials. Am. J. Cardiol. 2007, 100, S17–S24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.06.004.

- Konorza, T.F.M. Prospective, multi-center randomized trial to compare the implantation of a titanium-nitride-oxide coated stent with a paclitaxel stent in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Herz 2007, 32, 513. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00059-007-3036-6.

- Karjalainen, P.P.; Ylitalo, A.; Niemelä, M.; Kervinen, K.; Mäkikallio, T.; Pietilä, M.; Sia, J.; Tuomainen, P.; Nyman, K.; Airaksinen, K.E.J. Two-year follow-up after percutaneous coronary intervention with titanium-nitride-oxide-coated stents versus paclitaxel-eluting stents in acute myocardial infarction. Ann. Med. 2009, 41, 599–607. https://doi.org/10.1080/07853890903111018.

- Sant’Anna, F.M.; Batista, L.A.; Brito, M.B.; Menezes, S.; Ventura, F.M.; Buczynski, L.; Barrozo, C.A.M. Randomized comparison of percutaneous coronary intervention with titanium-nitride-oxide-coated stents versus stainless steel stents in patients with coronary artery disease: RIO trial. Rev. Bras. Cardiol. Invasia 2009, 17, 69–75.

- Dibra, A.; Tiroch, K.; Schulz, S.; Kelbæk, H.; Spaulding, C.; Laarman, G.J.; Valgimigli, M.; Di Lorenzo, E.; Kaiser, C.; Tierala, I.; et al. Drug-eluting stents in acute myocardial infarction: Updated meta-analysis of randomized trials. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2010, 99, 345–357. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00392-010-0133-y.

- Konorza, T.F.M. Randomized comparison of titanium-nitride-oxide coated stents with zotarolimus-eluting stents for coronary revascularisation. Herz 2010, 35, 364–367. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00059-010-3359-6.

- Moschovitis, A.; Simon, R.; Seidenstucker, A.; Klauss, V.; Baylacher, M.; Luscher, T.F.; Moccetti, T.; Windecker, S.; Meier, B.; Hess, O.M. Randomised comparison of titanium-nitride-oxide coated stents with bare metal stents: Five year follow-up of the TiNOX trial. EuroIntervention 2010, 6, 63–68.

- Karjalainen, P.; Nammas, W. Bioactive stents for percutaneous coronary intervention: A new forerunner on the track. Intervent. Cardiol. 2011, 3, 527–529. https://doi.org/10.2217/ica.11.61.

- Boden, H.; van der Hoeven, B.L.; Liem, S.S.; Atary, J.Z.; Cannegieter, S.C.; Atsma, D.E.; Bootsma, M.; Jukema, J.W.; Zeppenfeld, K.; Oemrawsingh, P.V.; et al. Five-year clinical follow-up from the MISSION! Intervention Study: Sirolimus-eluting stent versus bare metal stent implantation in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, a randomised controlled trial. EuroIntervention 2012, 7, 1021–1029. https://doi.org/10.4244/EIJV7I9A164.

- Lehtinen, T.; Airaksinen, K.E.; Ylitalo, A.; Karjalainen, P.P. Stent strut coverage of titanium-nitride-oxide coated stent compared to paclitaxel-eluting stent in acute myocardial infarction: TITAX-OCT study. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2012, 28, 1859–1866. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10554-012-0032-6.

- Tuomainen, P.O.; Ylitalo, A.; Niemelä, M.; Kervinen, K.; Pietilä, M.; Sia, J.; Nyman, K.; Nammas, W.; Airaksinen, K.E.J.; Karjalainen, P.P. Gender-based analysis of the 3-year outcome of bioactive stents versus paclitaxel-eluting stents in patients with acute myocardial infarction: An insight from the TITAX-AMI trial. J. Invasive Cardiol. 2012, 24, 104–108.

- De Luca, G.; Dirksen, M.T.; Spaulding, C.; Kelbk, H.; Schalij, M.; Thuesen, L.; Van der Hoeven, B.; Vink, M.A.; Kaiser, C.; Musto, C.; et al. Impact of Diabetes on Long-Term Outcome after Primary Angioplasty. Diabetes Care 2013, 36, 1020–1025.

- Karjalainen, P. Neointimal coverage and vasodilator response to titanium-nitride-oxide- coated bioactive stents and everolimus-eluting stents in patients with acute coronary syndrome: Insights from the BASE-ACS trial. Int. J. Card. Imaging 2013, 29, 1693–1703. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10554-013-0285-8.

- Lammer, J.; Zeller, T.; Hausegger, K.A.; Schaefer, P.J.; Gschwendtner, M.; Mueller-Huelsbeck, S.; Rand, T.; Funovics, M.; Wolf, F.; Rastan, A.; et al. Heparin-bonded covered stents versus bare-metal stents for complex femoropopliteal artery lesions: The randomized VIASTAR trial (viabahn endoprosthesis with propaten bioactive surface [VIA] versus bare nitinol stent in the treatment of long lesions in superficial femoral artery occlusive disease). J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013, 62, 1320–1327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.079.

- Romppanen, H.; Nammas, W.; Kervinen, K.; Mikkelsson, J.; Pietilä, M.; Lalmand, J.; Rivero-Crespo, F.; Pentikäinen, M.; Tedjokusumo, P.; Karjalainen, P.P. Outcome of ST-elevation myocardial infarction versus non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome treated with titanium-nitride-oxide-coated versus everolimus-eluting stents: Insights from the BASE-ACS trial. Minerva Cardioangiol. 2013, 61, 201–209.

- Velders, M.A.; Boden, H.; van der Hoeven, B.L.; Liem, S.S.; Atary, J.Z.; van der Wall, E.E.; Jukema, J.W.; Schalij, M.J. Long-term outcome of second-generation everolimus-eluting stents and Endeavor zotarolimus-eluting stents in a prospective registry of ST-elevation myocardial infarction patients. EuroIntervention 2013, 8, 1206.

- Huang, Y.; Ng, H.C.A.; Ng, X.W.; Subbu, V. Drug-eluting biostable and erodible stents. J. Control. Release 2014, 193, 188–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.05.011.

- López-Mínguez, J.R.; Nogales-Asensio, J.M.; Doncel-Vecino, L.J.; Merchán-Herrera, A.; Pomar-Domingo, F.; Martínez-Romero, P.; Fernández-Díaz, J.A.; Valdesuso-Aguilar, R.; Moreu-Burgos, J.; Díaz-Fernández, J. A randomized study to compare bioactive titanium stents and everolimus-eluting stents in diabetic patients (TITANIC XV): 1-year results. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. Engl. Ed. 2014, 67, 522–530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rec.2013.10.021.

- Ribamar Costa, J.; Almeida, B.O.; Costa, R.; Chamié, D.; Abizaid, A.; Perin, M.; Staico, R.; Feres, F.; Siqueira, D.; Veloso, M.; et al. Comparison of drug-eluting stents with durable or bioabsorbable polymer: Intracoronary ultrasound results of the BIOACTIVE trial. Rev. Bras. Cardiol. Invasia 2014, 22, 245–251.

- Tuomainen, P.O.; Sia, J.; Nammas, W.; Niemelä, M.; Airaksinen, J.K.; Biancari, F.; Karjalainen, P.P. Pooled analysis of two randomized trials comparing titanium-nitride-oxide-coated stent versus drug-eluting stent in STEMI. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. Engl. Ed. 2014, 67, 531–537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rec.2014.01.024.

- Bosiers, M.; Deloose, K.; Callaert, J.; Verbist, J.; Hendriks, J.; Lauwers, P.; Schroë, H.; Lansink, W.; Scheinert, D.; Schmidt, A.; et al. Superiority of stent-grafts for in-stent restenosis in the superficial femoral artery: Twelve-month results from a multicenter randomized trial. J. Endovasc. Ther. 2015, 22, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/1526602814564385.

- Chamié, D.; Almeida, B.O.; Grandi, F.; Filho, E.M.; Costa, J.R.; Costa, R.; Staico, R.; Siqueira, D.; Feres, F.; Tanajura, L.F.; et al. Vascular response after implantation of biolimus A9-eluting stent with bioabsorbable polymer and everolimus-eluting stents with durable polymer. Results of the optical coherence tomography analysis of the BIOACTIVE randomized trial. Rev. Bras. Cardiol. Invasia 2015, 23, 28–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbci.2015.02.001.

- Sia, J.; Nammas, W.; Niemelä, M.; Airaksinen, J.K.E.; Lalmand, J.; Laine, M.; Tedjokusumo, P.; Nyman, K.; Biancari, F.; Karjalainen, P.P. Gender-based analysis of randomized comparison of bioactive versus everolimus-eluting stents in acute coronary syndrome. J. Cardiovasc. Med. 2015, 16, 197–203. https://doi.org/10.2459/JCM.0000000000000086.

- Karjalainen, P.P.; Airaksinen, J.K.E.; de Belder, A.; Romppanen, H.; Kervinen, K.; Sia, J.; Laine, M.; Nammas, W. Long-term outcome of early percutaneous coronary intervention in diabetic patients with acute coronary syndrome: Insights from the BASE ACS trial. Ann. Med. 2016, 48, 376–383. https://doi.org/10.1080/07853890.2016.1186829.

- Karjalainen, P.P.; Niemelä, M.; Pietilä, M.; Sia, J.; de Belder, A.; Rivero-Crespo, F.; de Bruyne, B.; Nammas, W. 4-Year outcome of bioactive stents versus everolimus-eluting stents in acute coronary syndrome. Scand. Cardiovasc. J. 2016, 50, 218–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/14017431.2016.1177198.

- Kayssi, A.; Al-Atassi, T.; Oreopoulos, G.; Roche-Nagle, G.; Tan, K.T.; Rajan, D.K. Drug-eluting balloon angioplasty versus uncoated balloon angioplasty for peripheral arterial disease of the lower limbs. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011319.pub2.

- Varho, V.; Kiviniemi, T.O.; Nammas, W.; Sia, J.; Romppanen, H.; Pietilä, M.; Airaksinen, J.K.; Mikkelsson, J.; Tuomainen, P.; Perälä, A.; et al. Early vascular healing after titanium-nitride-oxide-coated stent versus platinum-chromium everolimus-eluting stent implantation in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2016, 32, 1031–1039. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10554-016-0871-7.

- Karjalainen, P.; Paana, T.; Ylitalo, A.; Sia, J.; Nammas, W. Optical coherence tomography follow-up 18 months after titanium-nitride-oxide-coated versus everolimus-eluting stent implantation in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Acta Radiol. 2017, 58, 1077–1084. https://doi.org/10.1177/0284185116683573.

- Karjalainen, P.P.; Nammas, W. Titanium-nitride-oxide-coated coronary stents: Insights from the available evidence. Ann. Med. 2017, 49, 299–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/07853890.2016.1244353.

- Karjalainen, P.P.; Niemelä, M.; Laine, M.; Airaksinen, J.K.E.; Ylitalo, A.; Nammas, W. Usefulness of Post-coronary Dilation to Prevent Recurrent Myocardial Infarction in Patients Treated with Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for Acute Coronary Syndrome (from the BASE ACS Trial). Am. J. Cardiol. 2017, 119, 345–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.09.057.

- Nammas, W.; Airaksinen, J.K.E.; Romppanen, H.; Sia, J.; de Belder, A.; Karjalainen, P.P. Impact of Preexisting Vascular Disease on the Outcome of Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome: Insights from the Comparison of Bioactive Stent to the Everolimus-Eluting Stent in Acute Coronary Syndrome Trial. Angiology 2017, 68, 513–518. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003319716664266.

- Nammas, W.; de Belder, A.; Niemelä, M.; Sia, J.; Romppanen, H.; Laine, M.; Karjalainen, P.P. Long-term clinical outcome of elderly patients with acute coronary syndrome treated with early percutaneous coronary intervention: Insights from the BASE ACS randomized controlled trial: Bioactive versus everolimus-eluting stents in elderly patients. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2017, 37, 43–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2016.07.027.

- Varho, V.; Nammas, W.; Kiviniemi, T.O.; Sia, J.; Romppanen, H.; Pietilä, M.; Airaksinen, J.K.; Karjalainen, P.P. Comparison of two different sampling intervals for optical coherence tomography evaluation of neointimal healing response after coronary stent implantation. Int. J. Cardiol. 2017, 227, 194–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.11.173.

- Hsu, C.C.T.; Kwan, G.N.C.; Singh, D.; Rophael, J.A.; Anthony, C.; van Driel, M.L. Angioplasty versus stenting for infrapopliteal arterial lesions in chronic limb-threatening ischaemia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009195.pub2.

- Hernandez, J.M.D.; Moreno, R.; Gonzalo, N.; Rivera, R.; Linares, J.A.; Fernandez, G.V.; Menchero, A.G.; del Blanco, B.G.; Hernandez, F.; Gonzalez, T.B.; et al. The Pt-Cr everolimus-eluting stent with bioabsorbable polymer in the treatment of patients with acute coronary syndromes. Results from the SYNERGY ACS registry. Revasc. Med. 2019, 20, 705–710.

- Kayssi, A.; Al-Jundi, W.; Papia, G.; Kucey, D.S.; Forbes, T.; Rajan, D.K.; Neville, R.; Dueck, A.D. Drug-eluting balloon angioplasty versus uncoated balloon angioplasty for the treatment of in-stent restenosis of the femoropopliteal arteries. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012510.pub2.

- Kuroda, K.; Otake, H.; Shinohara, M.; Kuroda, M.; Tsuda, S.; Toba, T.; Nagano, Y.; Toh, R.; Ishida, T.; Shinke, T.; et al. Effect of rosuvastatin and eicosapentaenoic acid on neoatherosclerosis: The LINK-IT Trial. EuroIntervention 2019, 15, E1099–E1106. https://doi.org/10.4244/EIJ-D-18-01073.

- Collet, C.; Tonino, P.A.L.; Mizukami, T.; Pijls, N.H.J.; De Bruyne, B.; Karjalainen, P.P. Reply: The Randomized TIDES-ACS Trial. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2020, 13, 2444–2445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcin.2020.09.009.

- Kuno, T.; Takahashi, M.; Hamaya, R. The Randomized TIDES-ACS Trial. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2020, 13, 2444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcin.2020.08.004.

- Wardle, B.G.; Ambler, G.K.; Radwan, R.W.; Hinchliffe, R.J.; Twine, C.P. Atherectomy for peripheral arterial disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006680.pub3.

- Gómez-Lara, J.; Oyarzabal, L.; Brugaletta, S.; Salvatella, N.; Romaguera, R.; Roura, G.; Fuentes, L.; Pérez Fuentes, P.; Ortega-Paz, L.; Ferreiro, J.L.; et al. Coronary endothelial and microvascular function distal to polymer-free and endothelial cell-capturing drug-eluting stents. The randomized FUNCOMBO trial. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. Engl. Ed. 2021, 74, 1013–1022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rec.2021.01.007.

- Gomez-Lara, J.; Oyarzabal, L.; Ortega-Paz, L.; Brugaletta, S.; Romaguera, R.; Salvatella, N.; Roura, G.; Rivero, F.; Fuentes, L.; Alfonso, F.; et al. Coronary endothelium-dependent vasomotor function after drug-eluting stent and bioresorbable scaffold implantation. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021, 10, e022123. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.121.022123.

- Sia, J.; Nammas, W.; Collet, C.; De Bruyne, B.; Karjalainen, P.P. Comparative study of neointimal coverage between titanium-nitric oxide-coated and everolimus-eluting stents in acute coronary syndromes. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2023, 76, 150–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.recesp.2022.05.011.

References

- Bhatt, D.L.; Lopes, R.D.; Harrington, R.A. Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute Coronary Syndromes: A Review. JAMA 2022, 327, 662–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daoud, F.C.; Létinier, L.; Moore, N.; Coste, P.; Karjalainen, P.P. Efficacy and Safety of TiNO-Coated Stents versus Drug-Eluting Stents in Acute Coronary Syndrome: Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 3159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=90622 (accessed on 4 June 2023).

- Huang, X.; Lin, J.; Demner-Fushman, D. Evaluation of PICO as a knowledge representation for clinical questions. AMIA Annu. Symp. Proc. 2006, 2006, 359–363. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gotzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009, 339, b2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.; Green, S. (Eds.) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, version 5.1.0 updated March 2011; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; Available online: https://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org/ (accessed on 8 March 2018).

- Garcia-Garcia, H.M.; McFadden, E.P.; Farb, A.; Mehran, R.; Stone, G.W.; Spertus, J.; Onuma, Y.; Morel, M.A.; van Es, G.A.; Zuckerman, B.; et al. Standardized End Point Definitions for Coronary Intervention Trials: The Academic Research Consortium-2 Consensus Document. Eur. Heart J. 2018, 39, 2192–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savovic, J.; Weeks, L.; Sterne, J.A.; Turner, L.; Altman, D.G.; Moher, D.; Higgins, J.P. Evaluation of the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing the risk of bias in randomized trials: Focus groups, online survey, proposed recommendations and their implementation. Syst. Rev. 2014, 3, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, M.; Davey Smith, G.; Schneider, M.; Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997, 315, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, M.; Smith, G.D. Bias in location and selection of studies. BMJ 1998, 316, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbord, R.M.; Egger, M.; Sterne, J.A. A modified test for small-study effects in meta-analyses of controlled trials with binary endpoints. Stat. Med. 2006, 25, 3443–3457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterne, J.A.; Egger, M.; Smith, G.D. Systematic reviews in health care: Investigating and dealing with publication and other biases in meta-analysis. BMJ 2001, 323, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schünemann, H.; Brożek, J.; Guyatt, G.; Oxman, A. (Eds.) GRADE Handbook for Grading Quality of Evidence and Strength of Recommendations. The GRADE Working Group. 2013. Available online: https://gdt.gradepro.org/app/handbook/handbook.html (accessed on 11 July 2023).

- Guyatt, G.H.; Oxman, A.D.; Kunz, R.; Woodcock, J.; Brozek, J.; Helfand, M.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Jaeschke, R.; Vist, G.; et al. GRADE guidelines: 8. Rating the quality of evidence–indirectness. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011, 64, 1303–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyatt, G.H.; Oxman, A.D.; Montori, V.; Vist, G.; Kunz, R.; Brozek, J.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Djulbegovic, B.; Atkins, D.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; et al. GRADE guidelines: 5. Rating the quality of evidence–publication bias. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011, 64, 1277–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyatt, G.H.; Oxman, A.D.; Vist, G.E.; Kunz, R.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Schunemann, H.J.; Group, G.W. GRADE: An emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008, 336, 924–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Brignardello-Petersen, R.; Hultcrantz, M.; Mustafa, R.A.; Murad, M.H.; Iorio, A.; Traversy, G.; Akl, E.A.; Mayer, M.; Schunemann, H.J.; et al. GRADE Guidance 34: Update on rating imprecision using a minimally contextualized approach. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2022, 150, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GRADEpro GDT: GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool [Software]. McMaster University, 2021 (Developed by Evidence Prime., Inc.). Available online: https://gdt.gradepro.org (accessed on 11 July 2023).

- Guyatt, G.H.; Oxman, A.D.; Kunz, R.; Brozek, J.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Rind, D.; Devereaux, P.J.; Montori, V.M.; Freyschuss, B.; Vist, G.; et al. GRADE guidelines 6. Rating the quality of evidence–imprecision. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011, 64, 1283–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinberg, J.; Nielsen, E.E.; Greenhalgh, J.; Hounsome, J.; Sethi, N.J.; Safi, S.; Gluud, C.; Jakobsen, J.C. Drug-eluting stents versus bare-metal stents for acute coronary syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 8, CD012481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilgrim, T.; Räber, L.; Limacher, A.; Löffel, L.; Wenaweser, P.; Cook, S.; Stauffer, J.C.; Togni, M.; Vogel, R.; Garachemani, A.; et al. Comparison of titanium-nitride-oxide-coated stents with zotarolimus-eluting stents for coronary revascularization a randomized controlled trial. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2011, 4, 672–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilgrim, T.; Räber, L.; Limacher, A.; Wenaweser, P.; Cook, S.; Stauffer, J.C.; Garachemani, A.; Moschovitis, A.; Meier, B.; Jüni, P.; et al. Five-year results of a randomised comparison of titanium-nitride-oxide-coated stents with zotarolimus-eluting stents for coronary revascularisation. EuroIntervention 2015, 10, 1284–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonino, P.A.L.; Pijls, N.H.J.; Collet, C.; Nammas, W.; Van der Heyden, J.; Romppanen, H.; Kervinen, K.; Airaksinen, J.K.E.; Sia, J.; Lalmand, J.; et al. Titanium-Nitride-Oxide-Coated Versus Everolimus-Eluting Stents in Acute Coronary Syndrome: The Randomized TIDES-ACS Trial. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2020, 13, 1697–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karjalainen, P.P.; Ylitalo, A.; Niemelä, M.; Kervinen, K.; Mäkikallio, T.; Pietilä, M.; Sia, J.; Tuomainen, P.; Nyman, K.; Airaksinen, J. Titanium-nitride-oxide coated stents versus paclitaxel-eluting stents in acute myocardial infarction: A 12-months follow-up report from the TITAX AMI trial. EuroIntervention 2008, 4, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuomainen, P.O.; Ylitalo, A.; Niemelä, M.; Kervinen, K.; Pietilä, M.; Sia, J.; Nyman, K.; Nammas, W.; Airaksinen, K.E.; Karjalainen, P.P. Five-year clinical outcome of titanium-nitride-oxide-coated bioactive stents versus paclitaxel-eluting stents in patients with acute myocardial infarction: Long-term follow-up from the TITAX AMI trial. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013, 168, 1214–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karjalainen, P.P.; Niemelä, M.; Airaksinen, J.K.E.; Rivero-Crespo, F.; Romppanen, H.; Sia, J.; Lalmand, J.; De Bruyne, B.; DeBelder, A.; Carlier, M.; et al. A prospective randomised comparison of titanium-nitride-oxide-coated bioactive stents with everolimus-eluting stents in acute coronary syndrome: The BASE-ACS trial. EuroIntervention 2012, 8, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karjalainen, P.P.; Nammas, W.; Ylitalo, A.; de Bruyne, B.; Lalmand, J.; de Belder, A.; Rivero-Crespo, F.; Kervinen, K.; Airaksinen, J.K.E. Long-term clinical outcome of titanium-nitride-oxide-coated stents versus everolimus-eluting stents in acute coronary syndrome: Final report of the BASE ACS trial. Int. J. Cardiol. 2016, 222, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouisset, F.; Sia, J.; Mizukami, T.; Karjalainen, P.P.; Tonino, P.A.L.; Pijls, N.H.J.; Van der Heyden, J.; Romppanen, H.; Kervinen, K.; Airaksinen, J.K.E.; et al. Titanium-Nitride-Oxide-Coated vs Everolimus-Eluting Stents in Acute Coronary Syndrome: 5-Year Clinical Outcomes of the TIDES-ACS Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2023, 8, 703–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piccolo, R.; Bonaa, K.; Efthimiou, O.; Varenne, O.; Baldo, A.; Urban, P.; Kaiser, C.; de Belder, A.; Lemos, P.; Wilsgaard, T.; et al. Individual Patient Data Meta-analysis of Drug-eluting Versus Bare-metal Stents for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Chronic Versus Acute Coronary Syndromes. Am. J. Cardiol. 2022, 182, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchida, K.; Piek, J.J.; Neumann, F.J.; van der Giessen, W.J.; Wiemer, M.; Zeiher, A.M.; Grube, E.; Haase, J.; Thuesen, L.; Hamm, C.W.; et al. One-year results of a durable polymer everolimus-eluting stent in de novo coronary narrowings (The SPIRIT FIRST Trial). EuroIntervention 2005, 1, 266–272. [Google Scholar]

- Fajadet, J.; Wijns, W.; Laarman, G.J.; Kuck, K.H.; Ormiston, J.; Munzel, T.; Popma, J.J.; Fitzgerald, P.J.; Bonan, R.; Kuntz, R.E.; et al. Randomized, double-blind, multicenter study of the Endeavor zotarolimus-eluting phosphorylcholine-encapsulated stent for treatment of native coronary artery lesions: Clinical and angiographic results of the ENDEAVOR II trial. Circulation 2006, 114, 798–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenstein, E.L.; Wijns, W.; Fajadet, J.; Mauri, L.; Edwards, R.; Cowper, P.A.; Kong, D.F.; Anstrom, K.J. Long-term clinical and economic analysis of the Endeavor drug-eluting stent versus the Driver bare-metal stent: 4-year results from the ENDEAVOR II trial (Randomized Controlled Trial to Evaluate the Safety and Efficacy of the Medtronic AVE ABT-578 Eluting Driver Coronary Stent in De Novo Native Coronary Artery Lesions). JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2009, 2, 1178–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemos, P.A.; Moulin, B.; Perin, M.A.; Oliveira, L.A.; Arruda, J.A.; Lima, V.C.; Lima, A.A.; Caramori, P.R.; Medeiros, C.R.; Barbosa, M.R.; et al. Late clinical outcomes after implantation of drug-eluting stents coated with biodegradable polymers: 3-year follow-up of the PAINT randomised trial. EuroIntervention 2012, 8, 117–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchini, J.F.; Gomes, W.F.; Moulin, B.; Perin, M.A.; Oliveira, L.A.; Arruda, J.A.; Lima, V.C.; Lima, A.A.; Caramori, P.R.; Medeiros, C.R.; et al. Very late outcomes of drug-eluting stents coated with biodegradable polymers: Insights from the 5-year follow-up of the randomized PAINT trial. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 2014, 4, 480–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, C.; Galatius, S.; Erne, P.; Eberli, F.; Alber, H.; Rickli, H.; Pedrazzini, G.; Hornig, B.; Bertel, O.; Bonetti, P.; et al. Drug-eluting versus bare-metal stents in large coronary arteries. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 2310–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reifart, N.; Hauptmann, K.E.; Rabe, A.; Enayat, D.; Giokoglu, K. Short and long term comparison (24 months) of an alternative sirolimus-coated stent with bioabsorbable polymer and a bare metal stent of similar design in chronic coronary occlusions: The CORACTO trial. EuroIntervention 2010, 6, 356–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehilli, J.; Pache, J.; Abdel-Wahab, M.; Schulz, S.; Byrne, R.A.; Tiroch, K.; Hausleiter, J.; Seyfarth, M.; Ott, I.; Ibrahim, T.; et al. Drug-eluting versus bare-metal stents in saphenous vein graft lesions (ISAR-CABG): A randomised controlled superiority trial. Lancet 2011, 378, 1071–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valgimigli, M.; Tebaldi, M.; Borghesi, M.; Vranckx, P.; Campo, G.; Tumscitz, C.; Cangiano, E.; Minarelli, M.; Scalone, A.; Cavazza, C.; et al. Two-year outcomes after first- or second-generation drug-eluting or bare-metal stent implantation in all-comer patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: A pre-specified analysis from the PRODIGY study (PROlonging Dual Antiplatelet Treatment After Grading stent-induced Intimal hyperplasia studY). JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2014, 7, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, E.E.; Campos, C.M.; Ribeiro, H.B.; Lopes, A.C.; Esper, R.B.; Meirelles, G.X.; Perin, M.A.; Abizaid, A.; Lemos, P.A. First-in-man randomised comparison of a novel sirolimus-eluting stent with abluminal biodegradable polymer and thin-strut cobalt-chromium alloy: INSPIRON-I trial. EuroIntervention 2014, 9, 1380–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- de Belder, A.; de la Torre Hernandez, J.M.; Lopez-Palop, R.; O’Kane, P.; Hernandez Hernandez, F.; Strange, J.; Gimeno, F.; Cotton, J.; Diaz Fernandez, J.F.; Carrillo Saez, P.; et al. A prospective randomized trial of everolimus-eluting stents versus bare-metal stents in octogenarians: The XIMA Trial (Xience or Vision Stents for the Management of Angina in the Elderly). J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 63, 1371–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaiser, C.; Galatius, S.; Jeger, R.; Gilgen, N.; Skov Jensen, J.; Naber, C.; Alber, H.; Wanitschek, M.; Eberli, F.; Kurz, D.J.; et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of biodegradable-polymer biolimus-eluting stents: Main results of the Basel Stent Kosten-Effektivitats Trial-PROspective Validation Examination II (BASKET-PROVE II), a randomized, controlled noninferiority 2-year outcome trial. Circulation 2015, 131, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, P.; Meredith, I.T.; Abizaid, A.; Pocock, S.J.; Carrie, D.; Naber, C.; Lipiecki, J.; Richardt, G.; Iniguez, A.; Brunel, P.; et al. Polymer-free Drug-Coated Coronary Stents in Patients at High Bleeding Risk. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 2038–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valgimigli, M.; Patialiakas, A.; Thury, A.; McFadden, E.; Colangelo, S.; Campo, G.; Tebaldi, M.; Ungi, I.; Tondi, S.; Roffi, M.; et al. Zotarolimus-eluting versus bare-metal stents in uncertain drug-eluting stent candidates. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015, 65, 805–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaa, K.H.; Mannsverk, J.; Wiseth, R.; Aaberge, L.; Myreng, Y.; Nygard, O.; Nilsen, D.W.; Klow, N.E.; Uchto, M.; Trovik, T.; et al. Drug-Eluting or Bare-Metal Stents for Coronary Artery Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1242–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varenne, O.; Cook, S.; Sideris, G.; Kedev, S.; Cuisset, T.; Carrie, D.; Hovasse, T.; Garot, P.; El Mahmoud, R.; Spaulding, C.; et al. Drug-eluting stents in elderly patients with coronary artery disease (SENIOR): A randomised single-blind trial. Lancet 2018, 391, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabate, M.; Brugaletta, S.; Cequier, A.; Iniguez, A.; Serra, A.; Jimenez-Quevedo, P.; Mainar, V.; Campo, G.; Tespili, M.; den Heijer, P.; et al. Clinical outcomes in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction treated with everolimus-eluting stents versus bare-metal stents (EXAMINATION): 5-year results of a randomised trial. Lancet 2016, 387, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darkahian, M.; Peighambari, M.M. Comparison of the mid-term outcome between drug-eluting stent and bare metal stent implantation in patients undergoing primary PCI in Rajaie Heart Center January 2012–April 2013. Iran. Heart J. 2014, 15, 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Belkacemi, A.; Agostoni, P.; Nathoe, H.M.; Voskuil, M.; Shao, C.; Van Belle, E.; Wildbergh, T.; Politi, L.; Doevendans, P.A.; Sangiorgi, G.M.; et al. First results of the DEB-AMI (drug eluting balloon in acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction) trial: A multicenter randomized comparison of drug-eluting balloon plus bare-metal stent versus bare-metal stent versus drug-eluting stent in primary percutaneous coronary intervention with 6-month angiographic, intravascular, functional, and clinical outcomes. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012, 59, 2327–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitt, J.; Reeve, M.; Whitlam, H.; Pulikal, G.; Ment, N.; El Gaylani, N. Drug eluting versus bare metal stents in acute ST elevation myocardial infarction (DEVINE)—A randomised control trial. Eur. Heart J. 2007, 28, 206. [Google Scholar]

- Steinwender, C.; Hofmann, R.; Kypta, A.; Kammler, J.; Kerschner, K.; Grund, M.; Sihorsch, K.; Gabriel, C.; Leisch, F. In-stent restenosis in bare metal stents versus sirolimus-eluting stents after primary coronary intervention for acute myocardial infarction and subsequent transcoronary transplantation of autologous stem cells. Clin. Cardiol. 2008, 31, 356–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strozzi, M.; Anic, D. Comparison of stent graft, sirolimus stent, and bare metal stent implanted in patients with acute coronary syndrome: Clinical and angiographic follow-up. Croat. Med. J. 2007, 48, 348–352. [Google Scholar]

- Chechi, T.; Vittori, G.; Biondi Zoccai, G.G.; Vecchio, S.; Falchetti, E.; Spaziani, G.; Baldereschi, G.; Giglioli, C.; Valente, S.; Margheri, M. Single-center randomized evaluation of paclitaxel-eluting versus conventional stent in acute myocardial infarction (SELECTION). J. Interv. Cardiol. 2007, 20, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Yan, H.B.; Zhu, X.L.; Li, N.; Ai, H.; Wang, J.; Li, S.Y.; Yang, D. Firebird sirolimus eluting stent versus bare mental stent in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Chin. Med. J. Engl. 2007, 120, 863–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konig, A.; Leibig, M.; Rieber, J.; Schiele, T.M.; Theisen, K.; Siebert, U.; Gothe, R.M.; Klauss, V. Randomized comparison of dexamethasone-eluting stents with bare metal stent implantation in patients with acute coronary syndrome: Serial angiographic and sonographic analysis. Am. Heart J. 2007, 153, 979.e1–979.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabate, M.; Cequier, A.; Iniguez, A.; Serra, A.; Hernandez-Antolin, R.; Mainar, V.; Valgimigli, M.; Tespili, M.; den Heijer, P.; Bethencourt, A.; et al. Everolimus-eluting stent versus bare-metal stent in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (EXAMINATION): 1 year results of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2012, 380, 1482–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tierala, I.; Syvanne, M.; Kupari, M. Randomised comparison of a paclitaxel-eluting and a bare metal stent in STEMI-PCI. Am. J. Cardiol. 2006, 98, S78. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez, P.L.; Gimeno, F.; Ancillo, P.; Sanz, J.J.; Alonso-Briales, J.H.; Bosa, F.; Santos, I.; Sanchis, J.; Bethencourt, A.; Lopez-Messa, J.; et al. Role of the paclitaxel-eluting stent and tirofiban in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction undergoing postfibrinolysis angioplasty: The GRACIA-3 randomized clinical trial. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2010, 3, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribamar Costa, J., Jr.; Abizaid, A.; Sousa, A.; Siqueira, D.; Chamie, D.; Feres, F.; Costa, R.; Staico, R.; Maldonado, G.; Centemero, M.; et al. Serial greyscale and radiofrequency intravascular ultrasound assessment of plaque modification and vessel geometry at proximal and distal edges of bare metal and first-generation drug-eluting stents. EuroIntervention 2012, 8, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz de la Llera, L.S.; Ballesteros, S.; Nevado, J.; Fernandez, M.; Villa, M.; Sanchez, A.; Retegui, G.; Garcia, D.; Martinez, A. Sirolimus-eluting stents compared with standard stents in the treatment of patients with primary angioplasty. Am. Heart J. 2007, 154, 164.e1–164.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guagliumi, G.; Sirbu, V.; Bezerra, H.; Biondi-Zoccai, G.; Fiocca, L.; Musumeci, G.; Matiashvili, A.; Lortkipanidze, N.; Tahara, S.; Valsecchi, O.; et al. Strut coverage and vessel wall response to zotarolimus-eluting and bare-metal stents implanted in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: The OCTAMI (Optical Coherence Tomography in Acute Myocardial Infarction) Study. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2010, 3, 680–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remkes, W.S.; Badings, E.A.; Hermanides, R.S.; Rasoul, S.; Dambrink, J.E.; Koopmans, P.C.; The, S.H.; Ottervanger, J.P.; Gosselink, A.T.; Hoorntje, J.C.; et al. Randomised comparison of drug-eluting versus bare-metal stenting in patients with non-ST elevation myocardial infarction. Open Heart 2016, 3, e000455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, G.W.; Witzenbichler, B.; Guagliumi, G.; Peruga, J.Z.; Brodie, B.R.; Dudek, D.; Kornowski, R.; Hartmann, F.; Gersh, B.J.; Pocock, S.J.; et al. Heparin plus a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor versus bivalirudin monotherapy and paclitaxel-eluting stents versus bare-metal stents in acute myocardial infarction (HORIZONS-AMI): Final 3-year results from a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2011, 377, 2193–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valgimigli, M.; Campo, G.; Gambetti, S.; Bolognese, L.; Ribichini, F.; Colangelo, S.; de Cesare, N.; Rodriguez, A.E.; Russo, F.; Moreno, R.; et al. Three-year follow-up of the MULTIcentre evaluation of Single high-dose Bolus TiRofiban versus Abciximab with Sirolimus-eluting STEnt or Bare-Metal Stent in Acute Myocardial Infarction StudY (MULTISTRATEGY). Int. J. Cardiol. 2013, 165, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lorenzo, E.; De Luca, G.; Sauro, R.; Varricchio, A.; Capasso, M.; Lanzillo, T.; Manganelli, F.; Mariello, C.; Siano, F.; Pagliuca, M.R.; et al. The PASEO (PaclitAxel or Sirolimus-Eluting Stent Versus Bare Metal Stent in Primary Angioplasty) Randomized Trial. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2009, 2, 515–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaulding, C.; Teiger, E.; Commeau, P.; Varenne, O.; Bramucci, E.; Slama, M.; Beatt, K.; Tirouvanziam, A.; Polonski, L.; Stella, P.R.; et al. Four-year follow-up of TYPHOON (trial to assess the use of the CYPHer sirolimus-eluting coronary stent in acute myocardial infarction treated with BallOON angioplasty). JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2011, 4, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Magro, M.; Raber, L.; Heg, D.; Taniwaki, M.; Kelbaek, H.; Ostojic, M.; Baumbach, A.; Tuller, D.; von Birgelen, C.; Roffi, M.; et al. The MI SYNTAX score for risk stratification in patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention for treatment of acute myocardial infarction: A substudy of the COMFORTABLE AMI trial. Int. J. Cardiol. 2014, 175, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vink, M.A.; Dirksen, M.T.; Suttorp, M.J.; Tijssen, J.G.; van Etten, J.; Patterson, M.S.; Slagboom, T.; Kiemeneij, F.; Laarman, G.J. 5-year follow-up after primary percutaneous coronary intervention with a paclitaxel-eluting stent versus a bare-metal stent in acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: A follow-up study of the PASSION (Paclitaxel-Eluting Versus Conventional Stent in Myocardial Infarction with ST-Segment Elevation) trial. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2011, 4, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musto, C.; Fiorilli, R.; De Felice, F.; Patti, G.; Nazzaro, M.S.; Scappaticci, M.; Bernardi, L.; Violini, R. Long-term outcome of sirolimus-eluting vs bare-metal stent in the setting of acute myocardial infarction: 5-year results of the SESAMI trial. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013, 166, 399–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijnbergen, I.; Tijssen, J.; Brueren, G.; Peels, K.; van Dantzig, J.M.; Veer, M.V.; Koolen, J.J.; Michels, R.; Pijls, N.H. Long-term comparison of sirolimus-eluting and bare-metal stents in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Coron. Artery Dis. 2014, 25, 378–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atary, J.Z.; van der Hoeven, B.L.; Liem, S.S.; Jukema, J.W.; van der Bom, J.G.; Atsma, D.E.; Bootsma, M.; Zeppenfeld, K.; van der Wall, E.E.; Schalij, M.J. Three-year outcome of sirolimus-eluting versus bare-metal stents for the treatment of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (from the MISSION! Intervention Study). Am. J. Cardiol. 2010, 106, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmvang, L.; Kelbaek, H.; Kaltoft, A.; Thuesen, L.; Lassen, J.F.; Clemmensen, P.; Klovgaard, L.; Engstrom, T.; Botker, H.E.; Saunamaki, K.; et al. Long-term outcome after drug-eluting versus bare-metal stent implantation in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: 5 years follow-up from the randomized DEDICATION trial (Drug Elution and Distal Protection in Acute Myocardial Infarction). JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2013, 6, 548–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- British Cardiovascular Society; The National Institute for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research (NICOR). Myocardial Ischaemia National Audit Project (MINAP): 2021 Summary Report. 2021. Available online: https://www.nicor.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/MINAP-Domain-Report_2021_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2023).

- Neumann, J.T.; Gossling, A.; Sorensen, N.A.; Blankenberg, S.; Magnussen, C.; Westermann, D. Temporal trends in incidence and outcome of acute coronary syndrome. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2020, 109, 1186–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erol, M.K.; Kayikcioglu, M.; Kilickap, M.; Arin, C.B.; Kurt, I.H.; Aktas, I.; Gunes, Y.; Ozkan, E.; Sen, T.; Ince, O.; et al. Baseline clinical characteristics and patient profile of the TURKMI registry: Results of a nation-wide acute myocardial infarction registry in Turkey. Anatol. J. Cardiol. 2020, 24, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralapanawa, U.; Kumarasiri, P.V.R.; Jayawickreme, K.P.; Kumarihamy, P.; Wijeratne, Y.; Ekanayake, M.; Dissanayake, C. Epidemiology and risk factors of patients with types of acute coronary syndrome presenting to a tertiary care hospital in Sri Lanka. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2019, 19, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N’Guetta, R.; Yao, H.; Ekou, A.; N’Cho-Mottoh, M.P.; Angoran, I.; Tano, M.; Konin, C.; Coulibaly, I.; Anzouan-Kacou, J.B.; Seka, R.; et al. Prevalence and characteristics of acute coronary syndromes in a sub-Saharan Africa population. Ann. Cardiol. Angeiol. Paris 2016, 65, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeh, R.W.; Sidney, S.; Chandra, M.; Sorel, M.; Selby, J.V.; Go, A.S. Population trends in the incidence and outcomes of acute myocardial infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 2155–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManus, D.D.; Gore, J.; Yarzebski, J.; Spencer, F.; Lessard, D.; Goldberg, R.J. Recent trends in the incidence, treatment, and outcomes of patients with STEMI and NSTEMI. Am. J. Med. 2011, 124, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negi, P.C.; Merwaha, R.; Panday, D.; Chauhan, V.; Guleri, R. Multicenter HP ACS Registry. Indian Heart J. 2016, 68, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inohara, T.; Kohsaka, S.; Yamaji, K.; Iida, O.; Shinke, T.; Sakakura, K.; Ishii, H.; Amano, T.; Ikari, Y. Use of Thrombus Aspiration for Patients With Acute Coronary Syndrome: Insights From the Nationwide J-PCI Registry. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2022, 11, e025728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quagliariello, V.; Bisceglia, I.; Berretta, M.; Iovine, M.; Canale, M.L.; Maurea, C.; Giordano, V.; Paccone, A.; Inno, A.; Maurea, N. PCSK9 Inhibitors in Cancer Patients Treated with Immune-Checkpoint Inhibitors to Reduce Cardiovascular Events: New Frontiers in Cardioncology. Cancers 2023, 15, 1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, R.A.; Rossello, X.; Coughlan, J.J.; Barbato, E.; Berry, C.; Chieffo, A.; Claeys, M.J.; Dan, G.A.; Dweck, M.R.; Galbraith, M.; et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 3720–3826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Räber, L.; Ueki, Y.; Otsuka, T.; Losdat, S.; Haner, J.D.; Lonborg, J.; Fahrni, G.; Iglesias, J.F.; van Geuns, R.J.; Ondracek, A.S.; et al. Effect of Alirocumab Added to High-Intensity Statin Therapy on Coronary Atherosclerosis in Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction: The PACMAN-AMI Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2022, 327, 1771–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libby, P. The changing landscape of atherosclerosis. Nature 2021, 592, 524–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quagliariello, V.; Passariello, M.; Rea, D.; Barbieri, A.; Iovine, M.; Bonelli, A.; Caronna, A.; Botti, G.; De Lorenzo, C.; Maurea, N. Evidences of CTLA-4 and PD-1 Blocking Agents-Induced Cardiotoxicity in Cellular and Preclinical Models. J. Pers. Med. 2020, 10, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Vorst, E.P.; Doring, Y.; Weber, C. MIF and CXCL12 in Cardiovascular Diseases: Functional Differences and Similarities. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolakis, S.; Vogiatzi, K.; Amanatidou, V.; Spandidos, D.A. Interleukin 8 and cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc. Res. 2009, 84, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, M.J.; Richardson, P.D.; Woolf, N.; Katz, D.R.; Mann, J. Risk of Thrombosis in Human Atherosclerotic Plaques: Role of Extracellular Lipid, Macrophage, and Smooth Muscle Cell Content. Heart 1993, 69, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridker, P.M.; Everett, B.M.; Thuren, T.; MacFadyen, J.G.; Chang, W.H.; Ballantyne, C.; Fonseca, F.; Nicolau, J.; Koenig, W.; Anker, S.D.; et al. Antiinflammatory Therapy with Canakinumab for Atherosclerotic Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 1119–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| M-H Fixed-Effects RR and 95% CI after the Removal of: | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | None | TITAX-AMI | TIDE | BASE-ACS | TIDES-ACS | Robustness |

| MACE | 0.82 [0.68, 0.99] | 0.88 [0.71, 1.09] | N.A. | 0.82 [0.65, 1.04] | 0.74 [0.58, 0.95] | No |

| CD | 0.46 [0.28, 0.76] | 0.51 [0.30, 0.89] | N.A. | 0.31 [0.16, 0.61] | 0.59 [0.31, 1.11] | No |

| MI | 0.59 [0.44, 0.78] | 0.61 [0.44, 0.85] | N.A. | 0.60 [0.43, 0.85] | 0.54 [0.37, 0.80] | Yes |

| TLR | 1.03 [0.79, 1.33] | 1.03 [0.76, 1.38] | N.A. | 1.11 [0.81, 1.54] | 0.94 [0.66, 1.32] | Yes |

| probable or definite ST | 0.32 [0.19, 0.55] | 0.40 [0.22, 0.73] | N.A. | 0.30 [0.15, 0.58] | 0.25 [0.12, 0.55] | Yes |

| TD | 0.84 [0.63, 1.12] | 0.84 [0.61, 1.16] | N.A. | 0.76 [0.54, 1.08] | 1.03 [0.74, 1.45] | Yes |

| Outcome | Risk of Bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication Bias | Certainty of Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MACE | not serious | not serious | not serious | not serious a | none | ⨁⨁⨁⨁ HIGH |

| CD | not serious | not serious c | not serious | not serious b | none | ⨁⨁⨁⨁ HIGH |

| MI | not serious | not serious | not serious | not serious b | none | ⨁⨁⨁⨁ HIGH |

| TLR | not serious | not serious | not serious | serious d | none | ⨁⨁⨁◯ MODERATE |

| probable or definite ST | not serious | not serious | not serious | not serious b | none | ⨁⨁⨁⨁ HIGH |

| TD | not serious | not serious | not serious | serious e | none | ⨁⨁⨁◯ MODERATE |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Daoud, F.C.; Catargi, B.; Karjalainen, P.P.; Gerbaud, E. Five-Year Efficacy and Safety of TiNO-Coated Stents Versus Drug-Eluting Stents in Acute Coronary Syndrome: A Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6952. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12216952

Daoud FC, Catargi B, Karjalainen PP, Gerbaud E. Five-Year Efficacy and Safety of TiNO-Coated Stents Versus Drug-Eluting Stents in Acute Coronary Syndrome: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(21):6952. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12216952

Chicago/Turabian StyleDaoud, Frederic C., Bogdan Catargi, Pasi P. Karjalainen, and Edouard Gerbaud. 2023. "Five-Year Efficacy and Safety of TiNO-Coated Stents Versus Drug-Eluting Stents in Acute Coronary Syndrome: A Meta-Analysis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 21: 6952. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12216952

APA StyleDaoud, F. C., Catargi, B., Karjalainen, P. P., & Gerbaud, E. (2023). Five-Year Efficacy and Safety of TiNO-Coated Stents Versus Drug-Eluting Stents in Acute Coronary Syndrome: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(21), 6952. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12216952