Mycobacterial Infection in Recalcitrant Otomastoiditis: A Case Series and Literature Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design

3. Case Presentations

3.1. Case 1

3.2. Case 2

3.3. Case 3

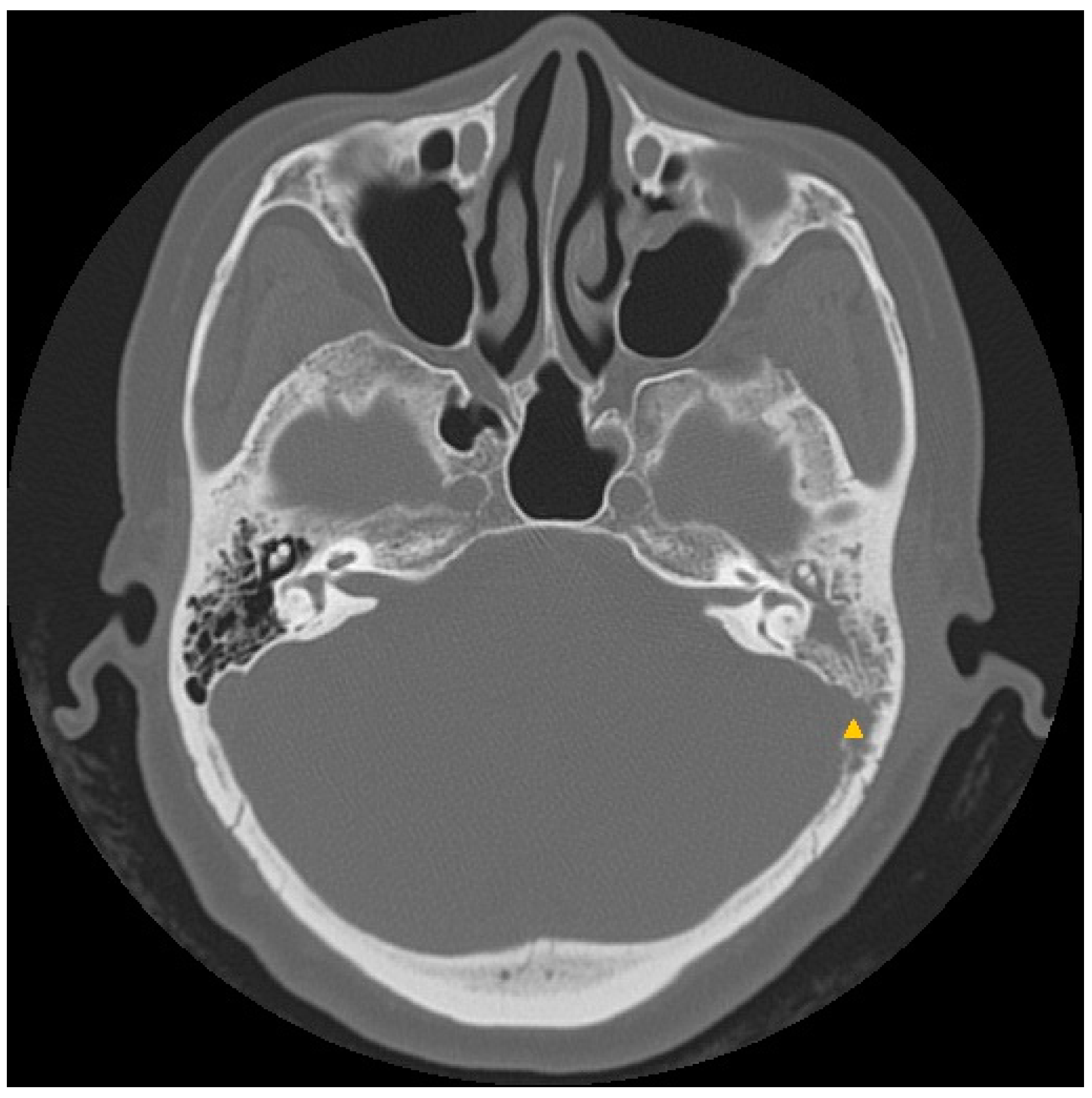

3.4. Case 4

3.5. Case 5

3.6. Case 6

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CSOM | Chronic suppurative otitis media |

| EAC | External auditory canal |

| HRCT | High-resolution computed tomography |

| NTM | Nontuberculous mycobacteria |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| TB | Tuberculosis |

| TOM | Tuberculous otomastoiditis |

References

- Vaamonde, P.; Castro, C.; García-Soto, N.; Labella, T.; Lozano, A. Tuberculous otitis media: A significant diagnostic challenge. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2004, 130, 759–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, R. Tuberculous otomastoiditis: A therapeutic and diagnostic challenge. Indian J. Otol. 2017, 23, 260–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.W.; Jin, J.W.; Rho, Y.S. Tuberculous otitis media developing as a complication of tympanostomy tube insertion. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2007, 264, 227–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flint, D.; Mahadevan, M.; Gunn, R.; Brown, S. Nontuberculous mycobacterial otomastoiditis in children: Four cases and a literature review. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 1999, 51, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundman, L.; Edvardsson, H.; Ängeby, K. Otomastoiditis caused by non-tuberculous mycobacteria: Report of 16 cases, 3 with infection intracranially. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2015, 129, 644–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, L.T.; Wang, C.Y.; Lin, C.D.; Tsai, M.H. Nontuberculous mycobacterial otomastoiditis: A case report. Ear Nose Throat J. 2013, 92, 31–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manders, J.; Leow, T.; van Aerde, K.; Hol, M.; Kunst, D.; Pegge, S.; Jansen, T.; van Ingen, J.; Bekkers, S. Clinical characteristics and an evaluation of predictors for a favourable outcome of Mycobacterium abscessus otomastoiditis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 116, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yorke, E.; Atiase, Y.; Akpalu, J.; Sarfo-Kantanka, O.; Boima, V.; Dey, I.D. The bidirectional relationship between tuberculosis and diabetes. Tuberc. Res. Treat. 2017, 2017, 1702578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sens, P.M.; Almeida, C.I.; Valle, L.O.; Costa, L.H.; Angeli, M.L. Tuberculosis of the ear, a professional disease? Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2008, 74, 621–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, O.T.; Clarke, A.R.; Drysdale, A.J. Challenges encountered in the diagnosis of tuberculous otitis media: Case report and literature review. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2011, 125, 738–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastian, S.K.; Singhal, A.; Sharma, A.; Doloi, P. Tuberculous otitis media -series of 10 cases. J. Otol. 2020, 15, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aremu, S.K.; Alabi, B.S. Tuberculous otitis media: A case presentation and review of the literature. BMJ Case Rep. 2010, 2010, bcr0220102721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirch, L.M.; Ahmad, K.; Spinner, W.; Jimenez, V.E.; Donelan, S.V.; Smouha, E. Tuberculous otitis media: Report of 2 cases on Long Island, N.Y., and a review of all cases reported in the United States from 1990 through 2003. Ear Nose Throat J. 2005, 84, 488, 490, 492 passim. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirsch, C.M.; Wehner, J.H.; Jensen, W.A.; Kagawa, F.T.; Campagna, A.C. Tuberculous otitis media. South. Med. J. 1995, 88, 363–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, P.Y.; Drysdale, A.J. Tuberculous otitis media: A difficult diagnosis. J. Laryngol. Otol. 1993, 107, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Paep, K.; Offeciers, F.E.; Van de Heyning, P.; Claes, J.; Marquet, J. Tuberculosis in the middle ear: 5 case reports. Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Belg. 1989, 43, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dardel, A.; Candau, P.; El-Bez, M. Tuberculose auriculaire—A propos de 2 cas. JF ORL. 2001, 50, 265–268. [Google Scholar]

- Awan, M.S.; Salahuddin, I. Tuberculous otitis media: Two case reports and literature review. Ear Nose Throat J. 2002, 81, 792–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.S.; Lee, H.S.; Kim, S.W.; Chung, K.H.; Lee, D.K.; Koh, W.J.; Kim, M.G. Tuberculous otitis media: A clinical and radiologic analysis of 52 patients. Laryngoscope 2006, 116, 921–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B. Role of surgery in tuberculous mastoiditis. J. Laryngol. Otol. 1991, 105, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, A.; Sabherwal, A.; Gulati, A.; Sareen, D. Primary tuberculous petrositis. Acta Otolaryngol. 2005, 125, 1236–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leow, T.Y.S.; Bekkers, S.; Janssen, A.M.; Pegge, S.A.H.; Kunst, H.P.M.; Waterval, J.J.; Jansen, T.T.G.; Henriet, S.S.V.; van Aerde, K.J.; van Ingen, J.; et al. Quality of life in children receiving treatment for Mycobacterium abscessus otomastoiditis. Clin. Otolaryngol. 2022, 47, 529–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palomino, J.C.; Martin, A. Drug resistance mechanisms in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antibiotics 2014, 3, 317–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxena, S.; Spaink, H.P.; Forn-Cuní, G. Drug resistance in nontuberculous mycobacteria: Mechanisms and models. Biology 2021, 10, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Case | Age (years)/Sex | Pathogen | Past History/Predisposing Factors | Clinical Features/Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 59/F | NTM a | Heart disease CSOM undergoing tympanoplasty | Mastoid cells abscess with granulation tissue |

| 2 | 66/M | TB b | Lung cancer | Bezold’s abscess |

| 3 | 61/F | TB c | DM | Mastoiditis, granulation |

| 4 | 49/M | TB b | None | Skull base osteomyelitis Right mastoid and cerebellar hemisphere involvement |

| 5 | 40/F | NTM a | VT insertion | Mastoiditis Skull base osteomyelitis |

| 6 | 58/F | NTM a | None | Poor wound healing after tympanoplasty with mastoidectomy |

| Case | Tissue Culture | PCR | Histopathology | Number of Operations | Poor Wound Healing | Time to Diagnosis (Months) | Treatment Course (Months) | Cured? | Sequelae |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Positive | M. abscessus |

| 4 | - | 7 | 6 | Yes | - |

| 2 | Negative | - |

| 4 | + | 4 | 6 | Yes | - |

| 3 | Negative | - |

| 2 | - | 1 | 9 | Yes | - |

| 4 | Negative | - |

| 0 | - | 1 | 12 | Yes | - |

| 5 | Positive | M. farcinogenes |

| 1 | - | 1 | 9 | Yes | - |

| 6 | Positive | M. abscessus |

| 2 | + | 4 | 9 | Yes | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tsai, T.; Lan, W.-C.; Mao, J.-S.; Lee, Y.-C.; Tsou, Y.-A.; Lin, C.-D.; Shih, L.-C.; Wang, C.-Y. Mycobacterial Infection in Recalcitrant Otomastoiditis: A Case Series and Literature Review. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 7279. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12237279

Tsai T, Lan W-C, Mao J-S, Lee Y-C, Tsou Y-A, Lin C-D, Shih L-C, Wang C-Y. Mycobacterial Infection in Recalcitrant Otomastoiditis: A Case Series and Literature Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(23):7279. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12237279

Chicago/Turabian StyleTsai, Tammy, Wei-Che Lan, Jit-Swen Mao, Yu-Chien Lee, Yung-An Tsou, Chia-Der Lin, Liang-Chun Shih, and Ching-Yuan Wang. 2023. "Mycobacterial Infection in Recalcitrant Otomastoiditis: A Case Series and Literature Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 23: 7279. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12237279