Abstract

Background: Late-onset hypogonadism (LOH) is a condition caused by the decline of testosterone levels with aging and is associated with various symptoms, including lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTSs). Although some reports have shown that testosterone replacement treatment for LOH improves LUTSs, no large study has revealed a correlation between LUTSs and LOH. This study investigated the correlation between the severity of LOH and LUTSs in Japanese males >40 years of age using a web-based questionnaire with the Aging Males’ Symptoms (AMS) scale. Methods: We asked 2000 Japanese males to answer both the AMS and IPSS/QOL questionnaires using a web-based survey. Among these 2000 individuals, 500 individuals were assigned to each age group. Results: The IPSS total score was positively correlated with the severity of AMS (shown as median [mean ± SD]): no/little group, 2 (3.67 ± 5.36); mild group, 6 (7.98 ± 6.91); moderate group, 11 (12.49 ± 8.63); and severe group, 16 (14.83 ± 9.24) (p < 0.0001). Conclusions: Individuals with higher AMS values, representing cases with severe LOH symptoms, had a higher risk of experiencing nocturia and LUTSs than those with lower AMS values.

1. Introduction

Late-onset hypogonadism (LOH) is a condition caused by the decline in testosterone levels with aging and is associated with various symptoms, including physical, psychological, and sexual disturbances [,]. Unlike menopause, in which all women undergo a nearly complete cessation of gonadal estrogen production, gonadal androgen production in men decreases progressively after the age of 40 years, but androgen levels among individuals remain highly variable. Previous studies have shown that serum testosterone levels decline between 0.4% and 2.6% per year in men after 40 years of age [,]. The symptoms of LOH include loss of muscle mass, increased body fat, anemia, osteoporosis, depressed mood, decreased vitality, sweating, hot flashes, loss of libido, and erectile dysfunction (ED). Among these, sexual symptoms, ED, and reduced libido are the most important symptoms related to LOH []. Liu et al. reported that the overall prevalence of androgen deficiency was 24.1% using the criterion of a total testosterone (TT) level < 300 ng/dL and 16.6% using the criterion of both TT < 300 ng/dL and free testosterone (FT) < 5 ng/dL. The prevalence of symptomatic androgen deficiency was 12.0%. Older age, obesity, and diabetes mellitus were associated with a significantly higher risk of androgen deficiency and symptomatic androgen deficiency in the Taiwanese population [].

LUTSs are symptoms associated with LOH. LUTSs can lead to urinary tract infection and upper urinary tract damage and can significantly decrease the quality of life []. LUTSs are prevalent in elderly men and women and are characterized by incomplete voiding, hesitancy, diminished stream, and storage indications such as urgency with incontinence, increased frequency, and nocturia. Significant morbidity and a potential increase in the risk of falls are observed [,]. Recent studies have shown that testosterone replacement therapy (TRT) can improve male LUTSs []. Although LOH worsens male LUTSs, most studies have investigated LUTSs in patients with LOH who present to the hospital [,,]. To date, no large-scale study has investigated the correlation between LOH severity and LUTSs in patients who have not visited a hospital.

The Aging Males’ Symptoms (AMS) scale, which is also validated in Japanese individuals, is widely accepted for the assessment and monitoring of symptoms of LOH; however, patients with an AMS score of 17–26 are not diagnosed with LOH []. In 1999, the Aging Males’ Symptoms (AMS) scale was developed as a symptom-profiling approach in Germany [] In the AMS, the severity of the symptoms of LOH is evaluated using the total score derived from all 17 questions, which assess parameters on a five-point scale [,]. The International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS), which includes seven domains and a QOL score, is widely used to assess the symptoms of male LUTSs []. The first version of the IPSS was created in 1992 by the American Urological Association (AUA). The IPSS consists of seven questions related to symptoms experienced in the last month, including a feeling of incomplete bladder emptying, frequency of urination, intermittency of urine stream, urgency of urination, weak stream, straining, and waking at night to urinate []. The current study used the Japanese language to validate IPSS and QOL scores to assess storage and voiding symptoms []. The questionnaire assessed voiding and storage symptoms.

The present study investigated the correlation between LOH severity and LUTSs in Asian Japanese males aged ≥40 years using a web-based questionnaire.

2. Materials and Methods

We asked 2000 Japanese males to answer both the AMS and IPSS/QOL questionnaires using a web-based survey (Freeasy, ibridge Inc., Tokyo, Japan) in August 2021. This survey was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Yokohama City University (Yokohama, Japan) [F220900015]. Of these 2000 individuals, 500 were assigned to each of the following age groups: 40–49, 50–59, 60–69, and ≥70 years. We randomly selected patients from 40,000 individual panels conducted by a web-based company. The AMS and IPSS/QOL questionnaires, which were validated in Japanese, were answered on a website.

LOH symptoms were assessed using the AMS score as no/little (17–26 points), mild (27–36 points), moderate (37–49 points), or severe (≥50 points) []. LUTSs were assessed through IPSS, and the severity was categorized as follows: mild (0–7 points), moderate (8–19 points), and severe (20–35 points) []. To compare the risk of voiding and storage dysfunction according to the severity of AMS, voiding dysfunction was assessed by the sum of IPSS Q1, Q3, Q5, and Q6, whereas storage dysfunction was assessed by the sum of IPSS Q2, Q4, and Q7 []. Nocturia was defined as a score of ≥2 points for IPSS Question 7. We also used the QOL index to assess the quality of daytime life in individuals with LUTSs.

Statistical Analyses

Participants’ characteristics and scores were analyzed using t-tests and chi-square tests. One-factor analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to evaluate the association between AMS scores and urinary symptoms. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software ver.10 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

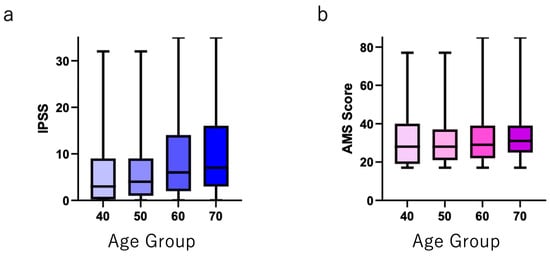

Five hundred individuals in each age group (40–49 years, 50–59 years, 60–69 years, and ≥70 years) answered both AMS and IPSS/QOL questionnaires. The distribution of the IPSS total, QOL, and AMS scores is shown in Supplementary Figure S1. Figure 1 shows that the IPSS total score was positively correlated with age. The IPSS total scores in each age group were as follows (shown as mean ± SD): 40–49 years, 5.95 ± 7.25; 50–59 years, 6.09 ± 6.79; 60–69 years, 8.71 ± 8.31; and ≥70 years, 10.14 ± 8.90 (p < 0.0001). The AMS scores (shown as the mean ± SD) were almost same in each age group: 40–49 years, 31.29 ± 13.6; 50–59 years, 30.48 ± 11.96; 60–69 years, 31.26 ± 11.55; and ≥70 years, 32.59 ± 11.06 (p = 0.0491).

Figure 1.

(a) Total IPSS and (b) total AMS scores in each age group.

The individual IPSS scores (Q1–Q7), IPSS total score, and QOL index for each AMS score group are shown in Table 1. The IPSS total score was positively correlated with the severity of AMS (shown as median [mean ± SD]): no/little group, 2 (3.67 ± 5.36); mild group, 6 (7.98 ± 6.91); moderate group, 11 (12.49 ± 8.63); and severe group, 16 (14.83 ± 9.24) (p < 0.0001). The QOL index was also positively correlated with the severity of AMS (shown as median [mean ± SD]): no/little group, 2 (2.19 ± 1.40); mild group, 3 (3.00 ± 1.38); moderate group, 3.5 (3.57 ± 1.40); and severe group, 4 (3.87 ± 1.50) (p < 0.000). Other IPSS scores, including Q7 (nocturia), were also positively correlated with AMS severity (Table 1).

Table 1.

IPSS/QOL score. The individual IPSS scores in each AMS severity group.

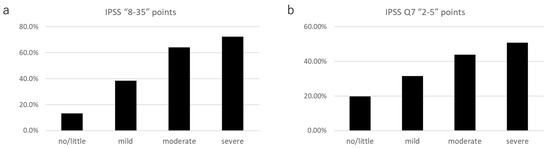

The prevalence of an IPSS total score of ≥8 in the AMS severity groups was as follows: no/little group, 13.3% (111 of 834); mild group, 38.3% (225 of 587); moderate group, 64.2% (244 of 380); and severe group, 72.4% (144/199) (Figure 2a). The prevalence of nocturia in the AMS severity groups was as follows: no/little, 19.8% (165 of 834); mild, 31.5% (185 of 587); moderate, 43.9% (167 of 380); and severe, 50.8% (101 of 199) (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

The prevalence of (a) IPSS ≥ 8; and (b) IPSS Q7 (nocturia) ≥ 2 in each AMS severity group.

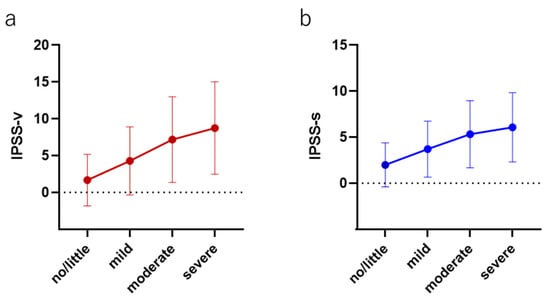

The median (mean ± SD) IPSS-v scores (voiding dysfunction) in each group were as follows: no/little group, 0 (1.67 ± 3.49); mild group, 3 (4.28 ± 4.68); moderate group, 6 (7.18 ± 5.81); and severe group, 9 (8.79 ± 6.29) (p > 0.0001). The median (mean ± SD) IPSS-s scores (storage dysfunction) were as follows: no/little group, 1 (2.00 ± 2.40); mild group, 3 (3.70 ± 3.04); moderate group, 5 (5.32 ± 3.64); and severe group, 6 (6.08 ± 3.77) (p > 0.0001). The relative scores of the IPSS-v and IPSS-s normalized by the score in the no/little group were positively correlated with the severity of AMS (IPSS-v: mild, 2.56; moderate, 4.29; and severe, 5.23; IPSS-s: mild, 1.85; moderate, 2.66; and severe, 3.04) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The correlation between both (a) voiding and (b) storage symptoms in each AMS severity group.

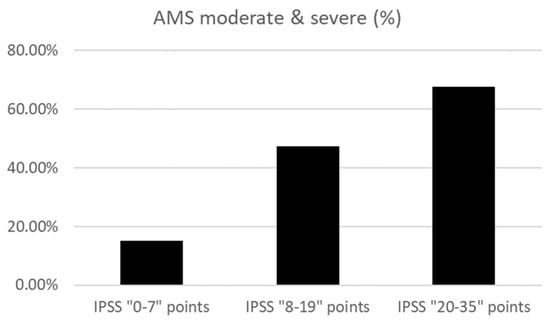

Figure 4 shows the prevalence of moderate or severe AMS in each IPSS severity group: IPSS total score 0–7 points, 15.0% (191 of 1276); IPSS total score 8–19 points, 47.4% (236 of 499); and IPSS total score 20–35 points, 67.6% (152 of 225). Raw data, including age, having a spouse or not, having children, and household income, are shown in the Supplementary Materials.

Figure 4.

The prevalence of moderate and severe AMS in each IPSS score group.

4. Discussion

This study revealed that patients with higher AMS scores had a higher prevalence of LUTSs and nocturia. These results also support previous studies that have reported that LOH symptoms worsen urinary symptoms []. Most previous studies have examined patients with LOH symptoms who visited hospitals. Therefore, studies to date have focused on patients with symptoms or other diseases, and not on those who were asymptomatic or had no occasion to seek medical attention. The present study assessed all individuals, including asymptomatic individuals. To date, this is the largest study to assess the correlation between LUTSs and increased AMS scores. Our findings support the notion that symptoms of LOH influence LUTSs.

The detailed mechanism underlying the association between LOH and LUTSs remains unclear. However, one possibility is that testosterone regulates nitric oxide (NO) production and that decreased testosterone levels result in lower NO production. Decreasing NO levels increase smooth muscle and pelvic muscle tone, which worsens LUTSs [,]. Amano et al. reported that patients with LOH had LUTSs, particularly voiding symptoms [,]. The present study also supported the previous study in that a stronger correlation was observed between the severity of AMS and the worsening of voiding symptoms in comparison to the severity of AMS and the worsening of storage symptoms.

This study also supported previous studies, as LUTSs worsened with an increase in the severity of LOH symptoms. In daily clinical practice, urologists sometimes encounter cases of male patients with LUTSs whose symptoms are not improved by treatment, including alpha-1 blockers, 5-alpha reductase, and endourological surgery. Based on evidence to support the efficacy of testosterone replacement treatment for the improvement of LUTSs in patients with LOH symptoms, ruling out LOH symptoms using the AMS score may be useful for determining appropriate treatment strategies for male patients with LUTSs.

Another potential mechanism is that low testosterone concentration influences an elevated blood glucose level, a worsening lipid profile, increased body weight, and increased blood pressure, causing problems such as atherosclerosis [,,]. Based on these mechanisms, LUTSs may be induced by LOH syndrome, and testosterone replacement treatment may restore these phenomena []. On the other hand, LUTSs sometimes improve after androgen deprivation therapy with 5-alpha reductase treatment due to a reduction in the prostate volume. We speculate that LUTSs worsen for a variety of reasons. LOH may be one of the factors that worsens LUTSs.

The present study was associated with some limitations. First, we evaluated LOH symptoms based on the AMS questionnaire and did not examine serum testosterone levels. Therefore, the clinical diagnosis was not determined. The AMS is widely used to assess the severity of LOH in daily clinical practice. Despite this limitation, a large number of individuals were evaluated in this short-term study, including men with no symptoms related to LOH. Second, this study did not assess other factors that can affect LUTSs, including smoking, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension [,]. Further studies are needed that include the evaluation of detailed information on the patients’ current state, history, and other factors.

5. Conclusions

Individuals with higher AMS scores, which reflect severe LOH symptoms, have a higher risk of nocturia and LUTSs.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jcm12247528/s1, Figure S1: Distribution of (a) total IPSS score, (b) QOL score, and (c) AMS score. Supplementally File S1: Raw data from web questionnaire.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.K.; methodology, T.K., S.N., T.T.; software, T.K.; validation, S.N., T.T., H.I., M.K., H.H.; data curation, H.I.; writing—original draft preparation, T.K.; writing—review and editing, T.K., H.H., K.M., H.U.; supervision, T.S., Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This survey was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Yokohama City University (Yokohama, Japan) [F220900015].

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

We uploaded raw data in supplementary file.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

References

- Amano, T.; Imao, T.; Takemae, K.; Iwamoto, T.; Nakanome, M. Testosterone replacement therapy by testosterone ointment relieves lower urinary tract symptoms in late onset hypogonadism patients. Aging Male 2010, 13, 242–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieschlag, E.; Swerdloff, R.; Behre, H.M.; Gooren, L.J.; Kaufman, J.M.; Legros, J.-J.; Lunenfeld, B.; Morley, J.E.; Schulman, C.; Wang, C.; et al. Investigation, treatment and monitoring of late-onset hypogonadism in males. Aging Male 2005, 8, 56–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, H.A.; Longcope, C.; Derby, C.A.; Johannes, C.B.; Araujo, A.B.; Coviello, A.D.; Bremner, W.J.; McKinlay, J.B. Age trends in the level of serum testosterone and other hormones in middle-aged men: longitudinal results from the Massachusetts male aging study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2002, 87, 589–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, S.M.; Metter, E.J.; Tobin, J.D.; Pearson, J.; Blackman, M.R. Longitudinal effects of aging on serum total and free testosterone levels in healthy men. Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001, 86, 724–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corona, G.; Krausz, C. Late-onset hypogonadism a challenging task for the andrology field. Andrology 2020, 8, 1504–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.-C.; Wu, W.-J.; Lee, Y.-C.; Wang, C.-J.; Ke, H.-L.; Li, W.-M.; Hsiao, H.-L.; Yeh, H.-C.; Li, C.-C.; Chou, Y.-H.; et al. The prevalence of and risk factors for androgen deficiency in aging Taiwanese men. J. Sex. Med. 2009, 6, 936–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yassin, D.J.; El Douaihy, Y.; Yassin, A.A.; Kashanian, J.; Shabsigh, R.; Hammerer, P.G. Lower urinary tract symptoms improve with testosterone replacement therapy in men with late-onset hypogonadism: 5-year prospective, observational and longitudinal registry study. World J. Urol. 2014, 32, 1049–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.S.; Huang, H.K.; Ding, D.C. Association of lower urinary tract symptoms and hip fracture in adults aged >/= 50 years. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrams, P.; Cardozo, L.; Fall, M.; Griffiths, D.; Rosier, P.; Ulmsten, U.; Van Kerrebroeck, P.; Victor, A.; Wein, A.; Standardisation Sub-Committee of the International Continence Society. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standardisation Sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2002, 21, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigehara, K.; Namiki, M. Late-onset hypogonadism syndrome and lower urinary tract symptoms. Korean J. Urol. 2011, 52, 657–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, K.; Miyake, H.; Ishida, T.; Sumii, K.; Enatsu, N.; Chiba, K.; Matsushita, K.; Fujisawa, M. Improved Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Associated with Testosterone Replacement Therapy in Japanese Men With Late-Onset Hypogonadism. Am. J. Men’s Health 2018, 12, 1403–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baas, W.; Kohler, T.S. Testosterone replacement therapy and voiding dysfunction. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2016, 5, 890–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thwaites, J.H. Practical aspects of drug treatment in elderly patients with mobility problems. Drugs Aging 1999, 14, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinemann, L.A.; Saad, F.; Zimmermann, T.; Novak, A.; Myon, E.; Badia, X.; Potthoff, P.; T’Sjoen, G.; Pöllänen, P.; Goncharow, N.P. The Aging Males’ Symptoms (AMS) scale: Update and compilation of international versions. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2003, 1, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akehi, Y.; Tanabe, M.; Yano, H.; Takashi, Y.; Kawanami, D.; Nomiyama, T.; Yanase, T. A simple questionnaire for the detection of testosterone deficiency in men with late-onset hypogonadism. Endocr. J. 2022, 69, 1303–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawahara, T.; Ito, H.; Uemura, H. The impact of smoking on male lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS). Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 20212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barry, M.J.; Fowler, F.J., Jr.; O’Leary, M.P.; Bruskewitz, R.C.; Holtgrewe, H.L.; Mebust, W.K.; Cockett, A.T.K.; The Measurement Committee of the American Urological Association. The American Urological Association symptom index for benign prostatic hyperplasia. J. Urol. 1992, 148, 1549–1557, discussion 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homma, Y.; Tsukamoto, T.; Yasuda, K.; Ozono, S.; Yoshida, M.; Shinji, M. Linguistic validation of Japanese version of International Prostate Symptom Score and BPH impact index. Nihon Hinyokika Gakkai Zasshi 2002, 93, 669–680. [Google Scholar]

- Becher, E.; Roehrborn, C.G.; Siami, P.; Gagnier, R.P.; Wilson, T.H.; Montorsi, F. The effects of dutasteride, tamsulosin, and the combination on storage and voiding in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostatic enlargement: 2-year results from the Combination of Avodart and Tamsulosin study. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2009, 12, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, S.W.; Jeon, J.H.; Kang, K.K.; Choi, S.B.; Park, J.K. Activity of phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors in patients with lower urinary tract symptoms due to benign prostatic hyperplasia. BJU Int. 2011, 107, 1943–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amano, T.I.T.; Takemae, K. Lower urinary tract symptom in patients with late-onset hypogonadism. Jpn. J. Impot. Res. 2009, 24, 359–365. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuru, T.; Tsujimura, A.; Mizushima, K.; Kurosawa, M.; Kure, A.; Uesaka, Y.; Nozaki, T.; Shirai, M.; Kobayashi, K.; Horie, S. International Prostate Symptom Score and Quality of Life Index for Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Are Associated with Aging Males Symptoms Rating Scale for Late-Onset Hypogonadism Symptoms. World J. Men’s Health 2023, 41, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamanoue, N.; Tanabe, M.; Tanaka, T.; Akehi, Y.; Murakami, J.; Nomiyama, T.; Yanase, T. A higher score on the Aging Males’ Symptoms scale is associated with insulin resistance in middle-aged men. Endocr. J. 2017, 64, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francomano, D.; Lenzi, A.; Aversa, A. Effects of five-year treatment with testosterone undecanoate on metabolic and hormonal parameters in ageing men with metabolic syndrome. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2014, 2014, 527470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawahara, T.; Ito, H.; Yao, M.; Uemura, H. Impact of smoking habit on overactive bladder symptoms and incontinence in women. Int. J. Urol. 2020, 27, 1078–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawahara, T.; Ninomiya, S.; Tsutsumi, S.; Ito, H.; Yao, M.; Uemura, H. Impact of depression on overactive bladder. Int. J. Urol. 2021, 28, 245–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).