Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Antagonists—A New Hope in Endometriosis Treatment?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Scales Used in Order to Measure Pelvic Pain

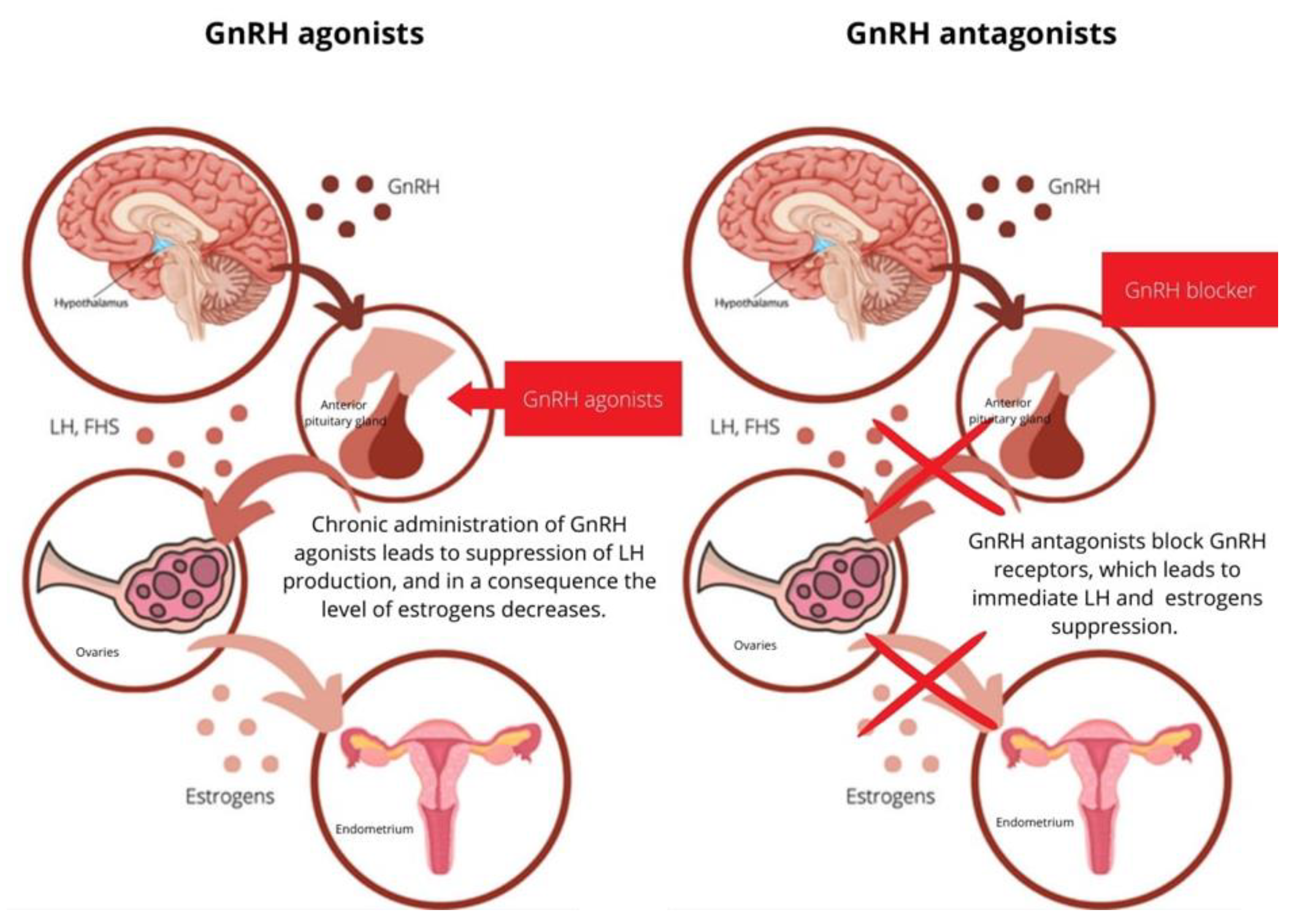

4. Mechanism of Action of GnRH Analogs

5. GnRH Antagonists in Endometriosis Treatment

5.1. Elagolix

5.2. Relugolix

5.3. Linzagolix

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vannuccini, S.; Clemenza, S.; Rossi, M.; Petraglia, F. Hormonal treatments for endometriosis: The endocrine background. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2022, 23, 333–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinatier, D.; Orazi, G.; Cosson, M.; Dufour, P. Theories of endometriosis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2001, 96, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burney, R.O.; Giudice, L.C. Pathogenesis and pathophysiology of endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 2012, 98, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mechsner, S.; Weichbrodt, M.; Riedlinger, W.F.J.; Bartley, J.; Kaufmann, A.M.; Schneider, A.; Köhler, C. Estrogen and progestogen receptor positive endometriotic lesions and disseminated cells in pelvic sentinel lymph nodes of patients with deep infiltrating rectovaginal endometriosis: A pilot study. Hum. Reprod. 2008, 23, 2202–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Malentacchi, F.; Fambrini, M.; Harrath, A.H.; Huang, H.; Petraglia, F. Epigenetics of Estrogen and Progesterone Receptors in Endometriosis. Reprod. Sci. 2020, 27, 1967–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benagiano, G.; Brosens, I.; Habiba, M. Structural and molecular features of the endomyometrium in endometriosis and adenomyosis. Hum. Reprod. Update 2014, 20, 386–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone Roberti Maggiore, U.; Ferrero, S.; Mangili, G.; Bergamini, A.; Inversetti, A.; Giorgione, V.; Vigano, P.; Candiani, M. A systematic review on endometriosis during pregnancy: Diagnosis, misdiagnosis, complications and outcomes. Hum. Reprod. Update 2016, 22, 70–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.K.; Chapron, C.; Giudice, L.C.; Laufer, M.R.; Leyland, N.; Missmer, S.A.; Singh, S.S.; Taylor, H.S. Clinical diagnosis of endometriosis: A call to action. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 220, 354.e1–354.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiesel, L.; Sourouni, M. Diagnosis of endometriosis in the 21st century. Climacteric 2019, 22, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcone, T.; Flyckt, R. Clinical Management of Endometriosis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 131, 557–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, J.Y.; Laufer, M.R. Adolescent Endometriosis: An Update. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2020, 33, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Defrère, S.; Lousse, J.C.; González-Ramos, R.; Colette, S.; Donnez, J.; Van Langendonckt, A. Potential involvement of iron in the pathogenesis of peritoneal endometriosis. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2008, 14, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signorile, P.G.; Baldi, F.; Bussani, R.; D’Armiento, M.; De Falco, M.; Boccellino, M.; Quagliuolo, L.; Baldi, A. New evidence of the presence of endometriosis in the human fetus. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2010, 21, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, J.D.; Hauck, A.E. Endometriosis in the male. Am. Surg. 1985, 51, 426–430. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Della Corte, L.; Di Filippo, C.; Gabrielli, O.; Reppuccia, S.; La Rosa, V.L.; Ragusa, R.; Fichera, M.; Commodari, E.; Bifulco, G.; Giampaolino, P. The Burden of Endometriosis on Women’s Lifespan: A Narrative Overview on Quality of Life and Psychosocial Wellbeing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 29, E4683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, S.; Bergqvist, A.; Chapron, C.; D’Hooghe, T.; Dunselman, G.; Greb, R.; Hummelshoj, L.; Prentice, A.; Saridogan, E.; on behalf of the ESHRE Special Interest Group for Endometriosis and Endometrium Guideline Development Group. ESHRE guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 2005, 20, 2698–2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunselman, G.; Vermeulen, N.; Becker, C.; Calhaz-Jorge, C.; D’Hooghe, T.; De Bie, B.; Heikinheimo, O.; Horne, A.W.; Kiesel, L.; Nap, A.; et al. ESHRE guideline: Management of women with endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 2014, 29, 400–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, C.M.; Bokor, A.; Heikinheimo, O.; Horne, A.; Jansen, F.; Kiesel, L.; King, K.; Kvaskoff, M.; Nap, A.; Petersen, K.; et al. ESHRE guideline: Endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. Open 2022, 2022. Published online 2022 Feb 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolarz, B.; Szyłło, K.; Romanowicz, H. Endometriosis: Epidemiology, Classification, Pathogenesis, Treatment and Genetics (Review of Literature). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 29, 10554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, K.; Kennedy, S.; Stratton, P. Pain scoring in endometriosis: Entry criteria and outcome measures for clinical trials. Report from the Art and Science of Endometriosis meeting. Fertil. Steril. 2010, 93, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biberoglu, K.O.; Behrman, S.J. Dosage aspects of danazol therapy in endometriosis: Short-term and long-term effectiveness. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1981, 139, 645–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, G.; Kennedy, S.; Barnard, A.; Wong, J.; Jenkinson, C. Development of anendometriosis quality-of-life instrument: The Endometriosis HealthProfile-30. Obstet. Gynecol. 2001, 98, 258–326. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jones, G.; Jenkinson, C.; Taylor, N.; Mills, A.; Kennedy, S. Measuring quality oflife in women with endometriosis: Tests of data quality, score reliability, response rate and scaling assumptions of the Endometriosis HealthProfile Questionnaire. Hum. Reprod. 2006, 21, 2686–2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renouvel, F.; Fauconnier, A.; Pilkington, H.; Panel, P. Linguistic adaptation ofthe endometriosis health profile 5: EHP-5. J. Gynécologie Obs. Biol. Reprod. 2009, 38, 404–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, G.; Jenkinson, C.; Kennedy, S. Development of the Short Form Endometriosis Health Profile Questionnaire: The EHP-5. Qual. Life Res. 2004, 13, 695–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selcuk, S.; Sahin, S.; Demirci, O.; Aksoy, B.; Eroglu, M.; Ay, P.; Cam, C. Translation and validation of the Endometriosis Health Profile (EHP-5) in patients with laparoscopically diagnosed endometriosis. Eur. J. Obs. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2015, 185, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubry, G.; Panel, P.; Thiollier, G.; Huchon, C.; Fauconnier, A. Measuring health-related quality of life in women with endometriosis: Comparing the clinimetric properties of the Endometriosis Health Profile-5 (EHP-5) and the EuroQol-5D (EQ-5D). Hum. Reprod. 2017, 32, 1258–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokrzywinski, R.M.; Soliman, A.M.; Snabes, M.C.; Chen, J.; Taylor, H.S.; Coyne, K.S. Responsiveness and thresholds for clinically meaningful changes in worst pain numerical rating scale for dysmenorrhea and nonmenstrual pelvic pain in women with moderate to severe endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2021, 115, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, O.; Bukulmez, O. Biochemistry, molecular biology and cell biology of gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonists. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011, 23, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.M.; Wang, H.S.; Huang, H.Y.; Lai, C.H.; Lee, C.L.; Soong, Y.K.; Leung, P.C. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone type II (GnRH-II) agonist regulates the invasiveness of endometrial cancer cells through the GnRH-I receptor and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)-dependent activation of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2. BMC Cancer 2013, 20, 13–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casañ, E.M.; Raga, F.; Bonilla-Musoles, F.; Polan, M.L. Human oviductal gonadotropin-releasing hormone: Possible implications in fertilization, early embryonic development, and implantation. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2000, 85, 1377–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, C.M.; Jolles, C.J.; Carrell, D.T.; Straight, R.C.; Jones, K.P.; Poulson, A.M.; Hatasaka, H.H. GnRH agonist therapy in human ovarian epithelial carcinoma (OVCAR-3) heterotransplanted in the nude mouse is characterized by latency and transience. Gynecol. Oncol. 1994, 52, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.Y.; Choi, K.C.; Auersperg, N.; Leung, P.C.K. Mechanism of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH)-I and -II-induced cell growth inhibition in ovarian cancer cells: Role of the GnRH-I receptor and protein kinase C pathway. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2006, 13, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khodr, G.S.; Siler-Khodr, T.M. Placental luteinizing hormone-releasing factor and its synthesis. Science 1980, 18, 315–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siler-Khodr, T.M.; Khodr, G.S. Extrahypothalamic luteinizing hormone-releasing factor (LRF): Release of immunoreactive LRF in vitro. Fertil. Steril. 1979, 32, 294–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casañ, E.M.; Raga, F.; Polan, M.L. GnRH mRNA and protein expression in human preimplantation embryos. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 1999, 5, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Kaganovsky, E.; Rahimipour, S.; Ben-Aroya, N.; Okon, E.; Koch, Y. Two forms of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) are expressed in human breast tissue and overexpressed in breast cancer: A putative mechanism for the antiproliferative effect of GnRH by down-regulation of acidic ribosomal phosphoproteins P1 and P2. Cancer Res. 2002, 62, 1036–1044. [Google Scholar]

- Stamatiades, G.A.; Kaiser, U.B. Gonadotropin regulation by pulsatile GnRH: Signaling and gene expression. Mol. Cell. Endcrinol. 2018, 463, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angioni, S.; D’Alterio, M.N.; Daniilidis, A. Highlights on Medical Treatment of Uterine Fibroids. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2021, 27, 3821–3832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depalo, R.; Jayakrishan, K.; Garruti, G.; Totaro, I.; Panzarino, M.; Giorgino, F.; Selvaggi, L. GnRH agonist versus GnRH antagonist in in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer (IVF/ET). Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2012, 10, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Eugster, E.A. Central Precocious Puberty: Update on Diagnosis and Treatment. Paediatr. Drugs 2015, 17, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, M.; Imai, A.; Takahashi, S.; Hirano, S.; Furui, T.; Tamaya, T. Advanced indications for gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues in gynecological oncology (review). Int. J. Oncol. 2003, 23, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klingmüller, D.; Schepke, M.; Enzweiler, C.; Bidlingmaier, F. Hormonal responses to the new potent GnRH antagonist Cetrorelix. Acta Endocrinol. 1993, 128, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blockeel, C.; Sterrenburg, M.D.; Broekmans, F.J.; Eijkemans, M.J.C.; Smitz, J.; Devroey, P.; Fauser, B.C. Follicular phase endocrine charateristics during ovarian stimulation and GnRH antagonist cotreatment for IVF: RCT comparing recFSH initiated on cycle day 2 or 5. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 96, 1122–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donnez, J.; Smoes, P.; Gillerot, S.; Casanas-Roux, F.; Nisolle, M. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 1998, 13, 1686–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLaren, J. Vascular endothelial growth factor and endometriotic angiogenesis. Hum. Reprod. Update 2000, 6, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meresman, G.F.; Bilotas, M.A.; Lombardi, E.; Tesone, M.; Sueldo, C.; Barañao, R.I. Effect of GnRH analogues on apoptosis and release of interleukin-1beta and vascular endothelial growth factor in endometrial cell cultures from patients with endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 2003, 18, 1767–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargiulo, A.R.; Hornstein, M.D. The role of GnRH agonists plus add-back therapy in the treatment of endometriosis. Semin. Reprod. Endocrinol. 1997, 15, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Chen, X.; Zhu, J.; Hua, K.; Hu, W. Effects and safety of gonadotrophin-releasing hormone agonist combined with estradiol patch and oral medroxyprogesterone acetate on endometriosis. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi 2009, 44, 504–508. [Google Scholar]

- Donnez, J.; Dolmans, M.M. GnRH Antagonists with or without Add-Back Therapy: A New Alternative in the Management of Endometriosis? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 20, 11342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. ORILISSATM (Elagolix) Tablets, for Oral Use Initial, U.S. Approval. 2018. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/210450s000lbl.pdf (accessed on 17 December 2022).

- Archer, D.F.; Stewart, E.A.; Jain, R.I.; Feldman, R.A.; Lukes, A.S.; North, J.D.; Soliman, A.M.; Gao, J.; Ng, J.W.; Chwalisz, K. Elagolix for the management of heavy menstrual bleeding associated with uterine fibroids: Results from a phase 2a proof-of-concept study. Fertil Steril. 2017, 108, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carr, B.; Giudice, L.; Dmowski, W.P.; O’Brien, C.; Jiang, P.; Burke, J.; Jimenez, R.; Hass, S.; Fuldeore, M.; Chwalisz, K. Elagolix, an Oral GnRH Antagonist for Endometriosis-Associated Pain: A Randomized Controlled Study. J. Endometr. Pelvic Pain Disord. 2013, 5, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diamond, M.P.; Carr, B.; Dmowski, W.P.; Koltun, W.; O’Brien, C.; Jiang, P.; Burke, J.; Jimenez, R.; Garner, E.; Chwalisz, K. Elagolix treatment for endometriosis-associated pain: Results from a phase 2, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Reprod. Sci. 2014, 21, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ács, N.; O’Brien, C.; Jiang, P.; Burke, J.; Jimenez, R.; Garner, E.; Chwalisz, K. Treatment of Endometriosis-Associated Pain with Elagolix, an Oral GnRH Antagonist: Results from a Phase 2, Randomized Controlled Study. J. Endometr. Pelvic Pain Disorders. 2015, 1, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, H.S.; Giudice, L.C.; Lessey, B.A.; Abrao, M.S.; Kotarski, J.; Archer, D.F.; Diamond, M.P.; Surrey, E.; Johnson, N.P.; Watts, N.B.; et al. Treatment of Endometriosis-Associated Pain with Elagolix, an Oral GnRH Antagonist. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 6, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shebley, M.; Polepally, A.R.; Nader, A.; Ng, J.W.; Winzenborg, I.; Klein, C.E.; Noertersheuser, P.; Gibbs, M.A.; Mostafa, N.M. Clinical Pharmacology of Elagolix: An Oral Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Receptor Antagonist for Endometriosis. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2020, 59, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, C.A. Reproductive endocrinology: Elagolix in endometriosis. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2017, 13, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surrey, E.; Taylor, H.S.; Giudice, L.; Lessey, B.A.; Abrao, M.S.; Archer, D.F.; Diamond, M.P.; Johnson, N.P.; Watts, N.B.; Gallagher, J.C.; et al. Long-Term Outcomes of Elagolix in Women With Endometriosis: Results From Two Extension Studies. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 132, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osuga, Y.; Enya, K.; Kudou, K.; Tanimoto, M.; Hoshiai, H. Oral Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Antagonist Relugolix Compared With Leuprorelin Injections for Uterine Leiomyomas: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 133, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myovant Sciences GmbH. LIBERTY 1: An International Phase 3 Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Efficacy and Safety Study to Evaluate Relugolix Co-Administered With and Without Low-Dose Estradiol and Norethindrone Acetate in Women With Heavy Menstrual Bleeding Associated With Uterine Fibroids—Report No.: NCT03049735. 2022. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03049735 (accessed on 17 November 2022).

- Myovant Sciences GmbH. LIBERTY 2: An International Phase 3 Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Efficacy and Safety Study to Evaluate Relugolix Co-Administered With and Without Low-Dose Estradiol and Norethindrone Acetate in Women With Heavy Menstrual Bleeding Associated With Uterine Fibroids—Report No.: NCT03103087. 2022. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03103087 (accessed on 17 November 2022).

- Osuga, Y.; Seki, Y.; Tanimoto, M.; Kusumoto, T.; Kudou, K.; Terakawa, N. Relugolix, an oral gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) receptor antagonist, in women with endometriosis-associated pain: Phase 2 safety and efficacy 24-week results. BMC Womens Health 2021, 21, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osuga, Y.; Seki, Y.; Tanimoto, M.; Kusumoto, T.; Kudou, K.; Terakawa, N. Relugolix, an oral gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor antagonist, reduces endometriosis-associated pain in a dose-response manner: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Fertil Steril. 2021, 115, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giudice, L.C.; As-Sanie, S.; Arjona Ferreira, J.C.; Becker, C.M.; Abrao, M.S.; Lessey, B.A.; Brown, E.; Dynowski, K.; Wilk, K.; Li, Y.; et al. Once daily oral relugolix combination therapy versus placebo in patients with endometriosis-associated pain: Two replicate phase 3, randomised, double-blind, studies (SPIRIT 1 and 2). Lancet 2022, 18, 2267–2279, Erratum in Lancet 2022, 27, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myovant Sciences GmbH. SPIRIT 2: An International Phase 3 Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Efficacy and Safety Study to Evaluate Relugolix Administered with and Without Low-Dose Estradiol and Norethindrone Acetate in Women With Endometriosis associated pain—Report No.: NCT03204331. 2022. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03204331 (accessed on 17 November 2022).

- Donnez, J.; Taylor, H.S.; Taylor, R.N.; Akin, M.D.; Tatarchuk, T.F.; Wilk, K.; Gotteland, J.P.; Lecomte, V.; Bestel, E. Treatment of endometriosis-associated pain with linzagolix, an oral gonadotropin-releasing hormone-antagonist: A randomized clinical trial. Fertil. Steril. 2020, 114, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ObsEva, S.A. A Double-blind Randomized Extension Study to Assess the Long-term Efficacy and Safety of Linzagolix in Subjects with Endometriosis-associated Pain. Report No.: NCT04372121. 2021. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04372121 (accessed on 17 November 2022).

- ObsEva, S.A. A Phase 3 Multicenter, Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled, Clinical Study to Assess the Efficacy and Safety of Linzagolix in Subjects with Moderate to Severe Endometriosis-associated Pain—Report No.: NCT03992846. 2022. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03992846 (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- ObsEva, S.A. Announces Additional Efficacy Results for Linzagolix 200 mg with Add-Back Therapy (ABT) and Linzagolix 75 mg without ABT in the Phase 3 EDELWEISS 3 Trial in Patients with Moderate-to-Severe Endometriosis-Associated Pain—GlobeNewswire News Room. 2022. Available online: https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2022/03/22/2407424/0/en/ObsEva-Announces-Additional-Efficacy-Results-for-Linzagolix-200-mg-with-Add-Back-Therapy-ABT-and-Linzagolix-75-mg-without-ABT-in-the-Phase-3-EDELWEISS-3-Trial-in-Patients-with-Mode.html (accessed on 21 November 2022).

- Donnez, J.; Donnez, O.; Tourniaire, J.; Brethous, M.; Bestel, E.; Garner, E.; Charpentier, S.; Humberstone, A.; Loumaye, E. Uterine Adenomyosis Treated by Linzagolix, an Oral Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Receptor Antagonist: A Pilot Study with a New ‘Hit Hard First and then Maintain’ Regimen of Administration. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 5794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnez, J.; Taylor, H.S.; Stewart, E.A.; Bradley, L.; Marsh, E.; Archer, D.; Al-Hendy, A.; Petraglia, P.; Watts, N.; Gotteland, J.-P.; et al. Linzagolix with and without hormonal add-back therapy for the treatment of symptomatic uterine fibroids: Two randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet 2022, 17, 896–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandoi, I.; Somigliana, E.; Riparini, J.; Ronzoni, S.; Vigano, P.; Candiani, M. High rate of endometriosis recurrence in young women. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2011, 24, 376–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, H.S. Emerging therapies for endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 2021, 1, 317–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, Y.N. Elagolix: First Global Approval. Drugs 2018, 78, 1501–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myovant Sciences and Pfizer Receive U.S. FDA Approval of MYFEMBREE®, a Once-Daily Treatment for the Management of Moderate to Severe Pain Associated with Endometriosis | Pfizer. 2022. Available online: https://www.pfizer.com/news/press-release/press-release-detail/myovant-sciences-and-pfizer-receive-us-fda-approval?fbclid=IwAR0_YBjJzBgmPA9kV5gX9F2li_y4pfye2ZnBO4QrQ57--2vG9_ek_MlclSY (accessed on 21 November 2022).

- Crosignani, P.G.; Luciano, A.; Ray, A.; Bergqvist, A. Subcutaneous depot medroxyprogesterone acetate versus leuprolide acetate in the treatment of endometriosis-associated pain. Hum. Reprod. 2006, 21, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buggio, L.; Dridi, D.; Barbara, G.; Merli, C.E.M.; Cetera, G.E.; Vercellini, P. Novel pharmacological therapies for the treatment of endometriosis. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2022, 15, 1039–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, H.S.; Giudice, L.C.; Lessey, B.A.; Abrao, M.; Kotarski, J.; Williams, L.A.; Rowan, J.; Chwalisz, K.; Duan, W.; Schwefel, B.; et al. Elagolix, an oral gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist, for the management of endometriosis-associated pain: Safety and efficacy results from two double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled studies. Fertil. Steril. 2016, 1, e271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, F.; Rich-Edwards, J.; Rimm, E.B.; Spiegelman, D.; Missmer, S.A. Endometriosis and Risk of Coronary Heart Disease. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2016, 9, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vercellini, P.; Viganò, P.; Barbara, G.; Buggio, L.; Somigliana, E.; ‘Luigi Mangiagalli’ Endometriosis Study Group. Elagolix for endometriosis: All that glitters is not gold. Hum. Reprod. 2019, 1, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, S.W.; Zhang, R.; Tan, Z.; Chung, J.P.W.; Zhang, T.; Wang, C.C. Pharmaceuticals targeting signaling pathways of endometriosis as potential new medical treatment: A review. Med. Res. Rev. 2021, 41, 2489–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbbVie. A Phase 3 Study to Evaluate the Safety and Efficacy of Elagolix in Combination With Estradiol/Norethindrone Acetate in Subjects With Moderate to Severe Endometriosis-Associated Pain—Report No.: NCT03213457. 2022. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03213457 (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Schlaff, W.D.; Ackerman, R.T.; Al-Hendy, A.; Archer, D.F.; Barnhart, K.T.; Bradley, L.D.; Carr, B.R.; Feinberg, E.C.; Hurtado, S.M.; Kim, J.; et al. Elagolix for Heavy Menstrual Bleeding in Women with Uterine Fibroids. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 23, 328–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hendy, A.; Lukes, A.S.; Poindexter, A.N., III; Venturella, R.; Villarroel, C.; McKain, L.; Li, Y.; Wagman, R.B.; Stewart, E.A. Long-term Relugolix Combination Therapy for Symptomatic Uterine Leiomyomas. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 1, 920–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, H.S.; Kotlyar, A.M.; Flores, V.A. Endometriosis is a chronic systemic disease: Clinical challenges and novel innovations. Lancet 2021, 27, 839–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Drug Category | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | Reversibly inhibit COX-1 and COX-2, which results in a decreased level of prostaglandin formation |

| Combined estrogen–progestin contraceptives | Inhibit FSH and LH, decrease cell proliferation and enhance endometrial apoptosis |

| Progestin-only preparations | Inhibit FSH and LH and stimulate atrophy or regression of endometrial lesions |

| Androgens | Antiestrogens inhibit enzymes involved in steroid formation and decrease the release of gonadotropin |

| Aromatase inhibitors | Block conversion of androgenesis to estrogen, which decreases endometrial proliferation |

| GnRH agonists | Chronic administration inhibits steroidogenesis due to the reduced LH and FSh levels. The initial hormone flare is characteristic of GnRH agonists |

| The Name of the Drug | The Name of the Randomized Clinical Trial and the Phase | The Location | The Population | The Sample Size | The Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elagolix | phase 2 Daisy PETAL trial | USA | women between 18 and 49 years old | 252 participants (169 completed trial) | reduction in dysmenorrhea, NMPP and dyspareunia, EAP |

| Elagolix | phase 2 Lilac PETAL trial | USA | women between 18 and 49 years old | 155 participants (127 completed trial) | reduction in dysmenorrhea and NMPP |

| Elagolix | phase 2 Tulip PETAL trial | USA | women between 18 and 45 years old | 174 participants (164 completed trial) | reduction in monthly mean pelvic pain and EAP |

| Elagolix | phase 3 Elaris Endometriosis 1 trial (EM-I) | USA, Canada | women between 18 and 49 years old | 872 participants (653 completed trial) | reduction in dysmenorrhea and NMPP |

| Elagolix | phase 3 Elaris Endometriosis 2 trial (EM-II) | Argentina, Austria, Australia, Brazil, Czech Republic, Hungary, Italy, New Zealand, Poland, South Africa, Spain, USA, the United Kingdom | women between 18 and 49 years old | 815 participants (632 completed trial) | reduction in dysmenorrhea and NMPP |

| Elagolix | phase 3 Elaris Endometriosis 3 trial (EM-III) | USA, Puerto Rico, Canada. | women between 18 and 49 years old | 287 participants (226 completed trial) | reduction in dysmenorrhea, NMPP and dyspareunia |

| Elagolix | phase 3 Elaris Endometriosis 4 trial (EM-IV) | North and South America, Europe, Australia/New Zealand, South Africa | women between 18 and 49 years old | 282 participants (232 completed trial) | reduction in dysmenorrhea, NMPP and dyspareunia |

| Relugolix | phase 3 trial | Japan | women aged 20 and older | 281 | reduction in EAP |

| Relugolix | phase 3 Liberty 1 trial | USA, Brazil, Italy, Poland, South Africa, the United Kingdom | women between 18 and 50 years old | 388 participants (308 completed trial) | decreased menstrual bleeding and preserved BMD in women with uterine fibroids |

| Relugolix | phase 3 Liberty 2 trial | USA, Belgium, Brazil, Chile, Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, South Africa | women between 18 and 50 years old | 382 participants (302 completed trial) | decreased menstrual bleeding and preserved BMD in women with uterine fibroids |

| Relugolix | phase 2 trial | Japan | women between 20 and 50 years old | 487 participants | reduction in EAP |

| Relugolix | phase 3 SPIRIT 1 trial | USA, Canada, Bulgaria, Polan Ukraine, Czech Republic, Finland, Hungary, Portugal, Spain, South Africa | women between 18 and 50 years old | 638 participants (540 completed trial) | reduction in dysmenorrhea, NMPP and EAP |

| Relugolix | phase 3 SPIRIT 2 trial | Australia, Brazil, Chile, Czechia, Georgia, Italy, New Zealand, Poland, Romania, Sweden, USA | women between 18 and 50 years old | 623 participants (508 completed trial) | reduction in dysmenorrhea, NMPP and EAP |

| Linzagolix | phase 2b EDELWEISS 1 trial | USA, Europe | women between 18 and 45 years old | 328 participants (323 completed trial) | reduction in EAP and improved quality of life |

| Linzagolix | phase 3 EDELWEISS 2 trial | USA, Canada, Puerto Rico | women between 18 and 50 years old | 30 participants | reduction in pelvic pain, dysmenorrheal pain |

| Linzagolix | phase 3 EDELWEISS 3 trial | USA, Poland, Czech Republic, Austria, Romania, Ukraine, France, Spain, Bulgaria | women between 18 and 50 years old | 288 participants | reduction in dysmenorrhea and NMPP, improvement in dyschezia and lowered worst pelvic pain |

| Linzagolix | pilot study in the single center | Europe | women between 37 and 45 years old | 10 participants (8 completed trial) | average pelvic volume of women decreased, reduced pelvic pain, dyspareunia, and dyschezia |

| Linzagolix | phase 3 PRIMROSE 1 trial | USA | women aged 18 and older | 574 participants (511 completed trial) | decrease in the mean uterine volume by 31% |

| Linzagolix | phase 3PRIMROSE 2 trial | USA, Europe | women aged 18 and older | 534 participants (501 completed trial) | decrease in the mean uterine volume by 43% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rzewuska, A.M.; Żybowska, M.; Sajkiewicz, I.; Spiechowicz, I.; Żak, K.; Abramiuk, M.; Kułak, K.; Tarkowski, R. Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Antagonists—A New Hope in Endometriosis Treatment? J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1008. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12031008

Rzewuska AM, Żybowska M, Sajkiewicz I, Spiechowicz I, Żak K, Abramiuk M, Kułak K, Tarkowski R. Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Antagonists—A New Hope in Endometriosis Treatment? Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(3):1008. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12031008

Chicago/Turabian StyleRzewuska, Anna Maria, Monika Żybowska, Ilona Sajkiewicz, Izabela Spiechowicz, Klaudia Żak, Monika Abramiuk, Krzysztof Kułak, and Rafał Tarkowski. 2023. "Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Antagonists—A New Hope in Endometriosis Treatment?" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 3: 1008. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12031008

APA StyleRzewuska, A. M., Żybowska, M., Sajkiewicz, I., Spiechowicz, I., Żak, K., Abramiuk, M., Kułak, K., & Tarkowski, R. (2023). Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Antagonists—A New Hope in Endometriosis Treatment? Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(3), 1008. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12031008