Abstract

Background: Biliary atresia (BA) is a rare cholangiopathy where one of the proposed aetiological mechanisms is an infectious viral trigger. Coronavirus disease-19 (COVID) lockdown restrictions were implemented to reduce the transmission of infections. Strictness of lockdown varied across European countries. This study aimed to investigate if there was an association between strictness of lockdown and change in isolated BA (IBA) incidence in Europe. Methods: We approached European centres involved in the European Reference Network RARE-LIVER. We included IBA patients born between 2015 and June 2020. We calculated the number of IBA patients born per centre per month. The Stringency Index (SI) was used as lockdown strictness indicator. The association between percentage change of mean number of IBA patients born per month and the SI was assessed. Results: We included 412 IBA patients from thirteen different centres. The median number of patients per month did not change: 6 (1–15) pre-lockdown and 7 (6–9) during lockdown (p = 0.34). There was an inverse association between SI and percentage change in IBA (B = -0.73, p = 0.03). Median age at Kasai portoenterostomy (days) did not differ between time periods (51 (9–179) vs. 53 (19–126), p = 0.73). Conclusion: In this European study, a stricter COVID-lockdown was seemingly accompanied by a simultaneous larger decrease in the number of IBA patients born per month in the lockdown. Results should be interpreted with caution due to the assumptions and limitations of the analysis.

1. Introduction

Biliary atresia (BA) is a rare disease of unknown origin. One hypothesis suggests that the pathophysiology involves a viral infection, followed by an over-activation of the immune response aimed at cholangiocytes [1,2]. This type of BA is termed isolated BA (IBA) to distinguish it from the syndromic form of BA, which is associated with developmental errors [2]. Prime viral candidates as the initiators of immune overactivation in IBA are rotavirus and cytomegalovirus (CMV) [3,4,5]. However, an unambiguous causal relationship between a virus and IBA has not been demonstrated yet, although CMV-IgM positivity is considered to define a separate subtype of BA [6,7,8]. Although a popular hypothesis, due to the lack of convincing evidence, the possibility of developmental and/or genetic factors playing a role in the pathophysiology of IBA cannot be excluded [9].

In February 2020, Europe was affected by the global pandemic caused by the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2 or COVID-19) [10]. As a consequence, many European countries took protective measures to reduce the exposure of the general population to people infected with COVID-19. Initial measures consisted of measures increasing personal hygiene, such as frequent hand washing with alcohol-based hand sanitiser or soap, and social measures such as social distancing oneself in order to minimise the risks of contracting infectious droplets when a person sneezes or speaks [11,12,13]. In March 2020, more drastic measures to reduce the transmission of COVID-19 were taken. Most European countries went into various degrees of lockdown, meaning closure of public primary and secondary schools, day-care centres as well as all public places such as restaurants and sport clubs. Generally, this first strict lockdown lasted from March 2020 up to and including May 2020 in most European countries. Although aimed to reduce COVID-19-related transmission, the transmission of non-COVID-19 viruses and bacteria was also affected by these strict measures. For example, in the Netherlands, a sharp decrease in the number of paediatric infectious diseases such as the common flu, otitis media and gastroenteritis was observed [14].

We hypothesised that these lockdowns might have had an effect on the incidence of IBA, thereby offering further support for an (infectious) environmental origin of this still enigmatic disease. Strictness of lockdown was not similar across Europe, with various measures applied in different countries. We therefore hypothesised that the strictness of lockdown would be associated with a decrease in IBA incidence, with a stricter lockdown leading to a more pronounced decrease in IBA incidence. Therefore, we performed a collaborative European-wide study that aimed to investigate the incidence of IBA during the lockdown period in different European countries and to assess the association between strictness of lockdown and IBA incidence.

2. Materials and Methods

We invited members of the European Reference Network RARE-Liver and the Biliary Atresia and Related Disorders (BARD) community to provide data on IBA patients treated in their centres prior to and during the COVID pandemic. The ERN RARE-Liver is a Europe-wide network for centres of expertise in the clinical management of rare liver diseases, for example BA and choledochal malformation. BARD is a collaborative initiative to perform international research on BA and related diseases. This study was performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Medical Ethical Committee of the University Medical Centre Groningen (2017/056).

We collected patient data of BA patients born between 2015 and 2021 via a REDCap online database [15]. Clinical variables were date of birth, place of birth and age at primary treatment (Kasai portoenterostomy (KPE) or primary liver transplantation). Patients were excluded for this study if (1) they did not have the isolated variant of BA, (2) if their primary treatment did not take place in the participating centre (KPE or primary liver transplantation) or (3) if they were born outside of the country in which the participating centre is located. Patients were considered as non-isolated according to when they had biliary atresia splenic malformation (BASM) syndrome or a congenital abnormality that is associated with syndromal BA [9].

Strictness of lockdown was graded according to the ‘stringency index’ (SI). The SI is an open access index calculated based on multiple variables such as whether schools were closed during the lockdown or how strict the stay-at-home advice was. Each variable is scored separately from 0 to 100 from which an overall SI is calculated per country [16]. We selected items of the SI that we deemed relevant for the transmission of bacteria and viruses in children. Six items were included: school closing, stay at home advice, restrictions on public gatherings, restriction on public transport, cancellation of public events and closure of workplace.

The score of each included variable was calculated as described by Hale et al. [16]. Briefly, each included variable received a grade based on an ordinal scale every day during the lockdown period. The lockdown period was defined as the period from March 2020 up to and including May 2020. The ordinal grade was transformed to a score between 0 (no restriction) and 100 (maximum restriction) for every individual day. Subsequently, the mean score of each individual variable during the lockdown period was calculated. SI was calculated by averaging the mean score of each individual included variable during the lockdown period.

SI is an indirect measure of viral transmission and a higher SI does not necessarily indicate a more efficient response. SI is correlated to COVID-related deaths and, although still a surrogate marker with accompanying limitations, was therefore deemed an acceptable measure of strictness of lockdown and viral transmissions [17]. Furthermore, the daily number of COVID infections was limited by insufficient testing capacity, fluctuations and variable testing policy in different countries and was therefore unsuitable as surrogate marker.

Two time periods were defined: the period prior to the lockdown (i.e., 1 January 2015–29 February 2020) and the period of the strict lockdown (1 March 2020–31 May 2020). Date of birth of patients who presented with IBA was used to determine the number of patients born per month who acquired IBA per centre. Based on the date of birth, patients were either classified as born in the pre-lockdown period or the lockdown period.

Treatment for BA in a country can be centralised or non-centralised. When treatment of BA is centralised, BA patients are treated in one or a few designated centres. When treatment is non-centralised, multiple centres can treat BA patients with variable caseloads. For countries with centralised BA care, national data on all BA patients can be reliably obtained. When not all centres from a country where BA treatment is centralised participate or when centres from countries with non-centralised BA treatment participate, only a part of the national BA data can be obtained.

Incidence of IBA can only be calculated in countries with complete, national BA data because a reliable population at risk can be determined (i.e., live births). When only part of the national BA data is present, incidence cannot be calculated. Therefore, participating centres were divided into two groups based on whether national data or a part of the national data were present: national BA data and part of national BA data. When complete national BA data were available, country name is reported. When part of the national BA data was available, centre name is reported.

The median number of IBA patients born per month for all centres was combined and each centre (part of national data) or country (national data) was recorded separately. Mean number of IBA patients born per month was calculated. The percentage change in mean number of IBA patients born per month during the pre-lockdown period and lockdown period was calculated. This was completed for total IBA patients, per centre and per country.

For countries with national BA data, incidence of IBA was calculated. Incidence was calculated by dividing the number of IBA patients by the number of live births per country, multiplied by 10,000. Data on live births were retrieved from the national bureau of statistics from each respective country. Centres from the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Finland, Switzerland and Denmark had complete national BA data and were therefore included in this analysis. IBA incidence in the two time periods was compared.

Clustering of IBA in time is only found in some studies [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. However, to avoid any possible clustering in time to affect our analysis, we also compared the incidence of IBA during the lockdown period in 2020 and the IBA incidence in the three-month period of March–June in the years 2015 up to and including 2019.

To detect a potential delay in referral during the strict lockdown, we compared median age at time of KPE (excluding patients that were treated by a primary liver transplantation) in the period prior to the lockdown and in the lockdown of patients with IBA.

Statistical Analysis

Difference in the median number of IBA patients born per centre per month and age at KPE (when KPE was primary treatment) during the pre-lockdown and lockdown period was compared using the Mann–Whitney U test.

Calculated SI was treated as a continuous variable. The association between the percentage change in the mean number of IBA patients born per centre per month between each time period and SI was assessed using Spearman’s correlation coefficient. Percentage change was calculated as follows:

Percentage change = (mean IBA patients born per month in lockdown–mean IBA patients born per month in pre-lockdown)/mean IBA patients born per month in pre-lockdown.

To evaluate differences in incidence (i.e., national data), the incidence of IBA in the period prior to the lockdown was used as a reference category. IBA incidence during the lockdown was compared by using logistic binominal regression analysis and an odds ratio (OR) was displayed. We evaluated the association between SI and IBA incidence during the lockdown by using multivariate logistic regression. BA was used as a binominal dependent outcome, with SI as a continuous independent variable. Country was included as a categorial independent variable.

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS statistical software for Windows, version 23.0. (IBM corp, Armonk, NY, USA) and Stata Statistical Software: Release 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Graphs were created using GraphPad Prism version 8.4.2 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

3. Results

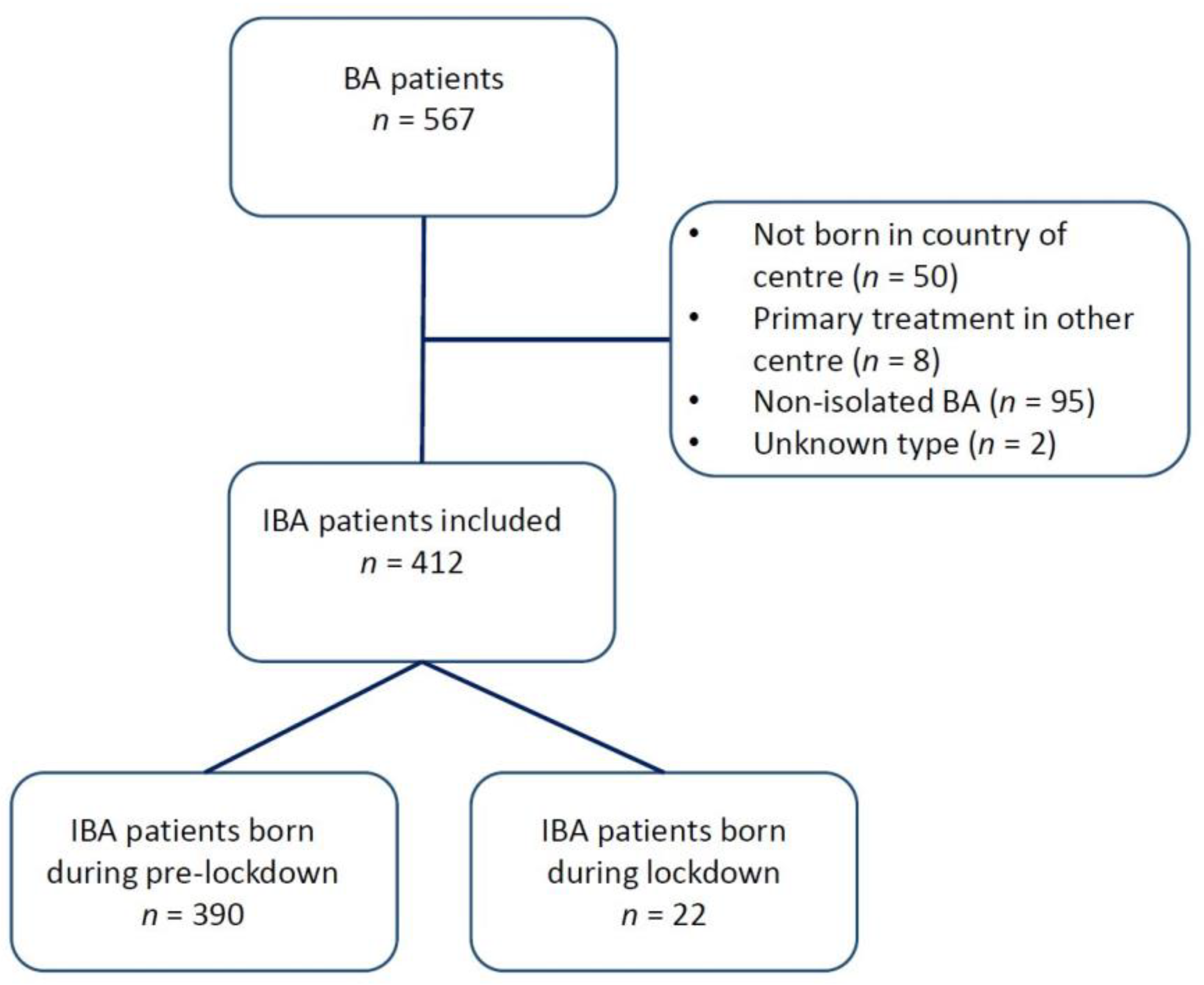

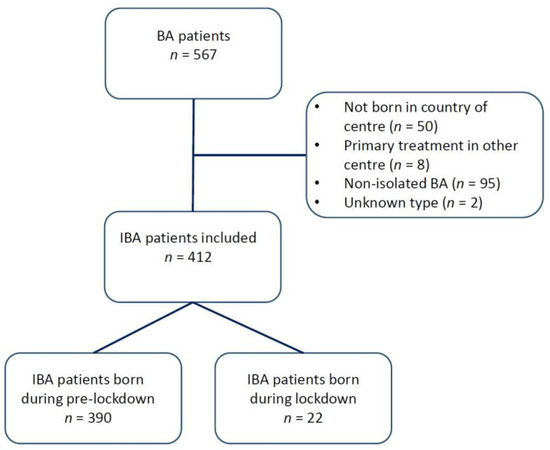

Thirteen centres from eight countries participated in this study, thereby including 412 patients. A total of 95 patients were classified as having a non-isolated form of BA and were excluded from the analysis. Figure 1 shows a flowchart of patient inclusion. An overview of the participating centres and the number of BA patients from each centre is shown in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of patients included in this study.

Table 1.

An overview of the participating centres and the number of BA patients that were treated in each centre and born between 1 January 2015 and 31 May 2020. A distinction is made between IBA and non-IBA patients. IBA patients were included in this study.

3.1. Number of IBA Patients before and during the Lockdown Period

Overall, prior to the lockdown, a median of 6 (range: 1–15) patients who acquired IBA were born per centre per month, versus 7 (6–9) during the lockdown period (p= 0.34, see Table 2).

Table 2.

Median number of IBA patients born per month per participating centre or country (national BA data).

In countries with national BA data a median number of 4 (1–13) and 3 (2–3) patients who acquired IBA were born in the pre-lockdown and lockdown period, respectively (p = 0.14). In centres from countries with part of national BA data, there was an increase in the median number of IBA patients when comparing the pre-lockdown and lockdown period: 2 (0–7) and 4 (4–6), respectively (p = 0.01).

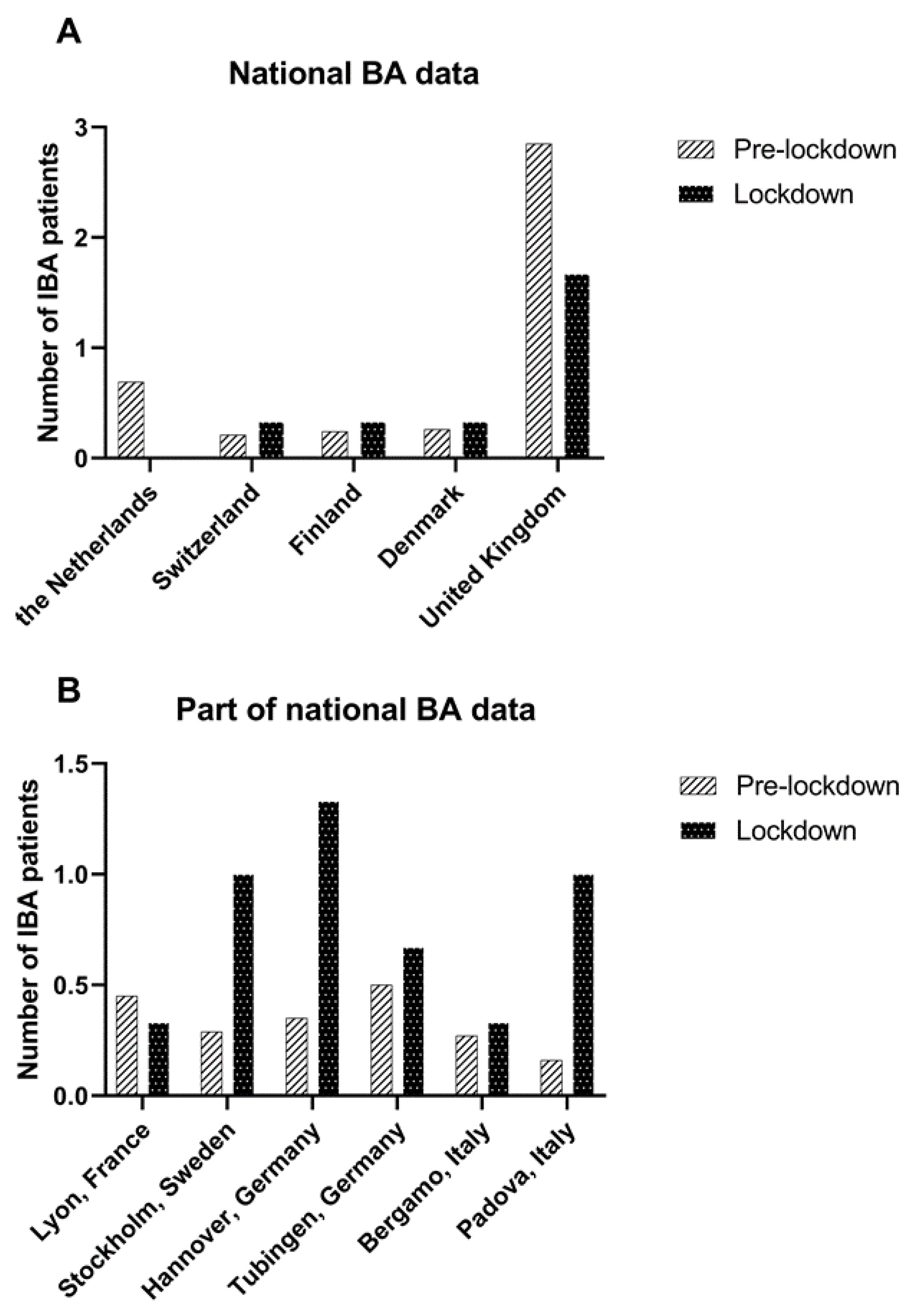

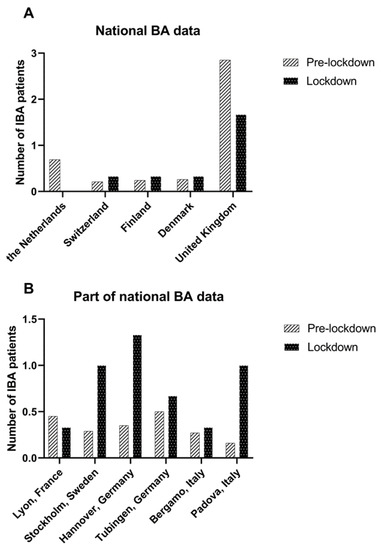

The median number of IBA patients born per month decreased strongly but was not statistically significant in the Netherlands (0.5 (0–3) vs. 0, 100% decrease, p = 0.11) and in the United Kingdom (3 (0–11) vs. 1 (1–3), 41.6% decrease, p = 0.17). Data from other countries/centres are shown in Table 2 and Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Mean number of IBA patients treated per month in the pre-lockdown period (January 2015 –March 2020) and lockdown period (March 2020–June 2020) in (A) countries with national BA data and (B) in centres from countries where a part of the national BA data was available.

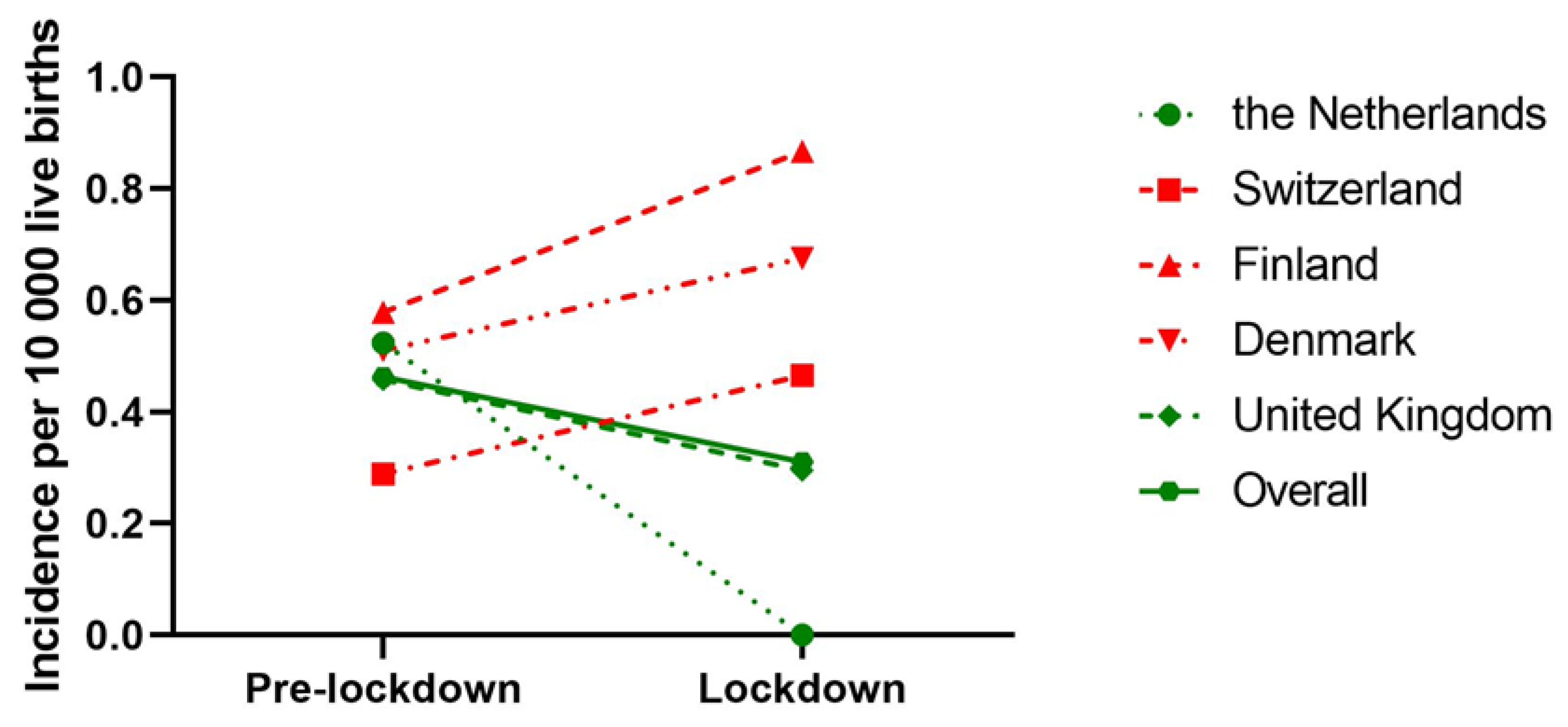

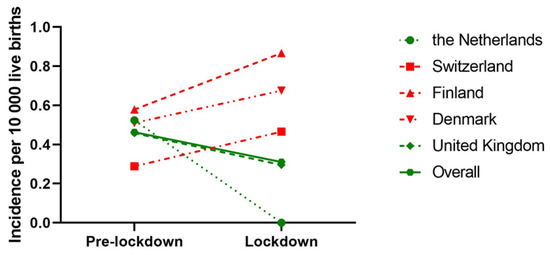

When we only considered countries with national BA data, 272 IBA patients from five countries, born between 1 January 2015 and 31 May 2020 were included. During the lockdown, the overall odds of acquiring IBA were 0.68 (95% CI: 0.34–1.37, p = 0.28) compared to the pre-lockdown period. The OR of acquiring IBA during the lockdown period compared to the pre-lockdown period decreased in the Netherlands (OR: 0.25 [95% CI: 0.01–4.03, p = 0.33]) and United Kingdom (OR: 0.64 [95%CI: 0.26–1.57, p = 0.33]); however, this failed to reach statistical significance (Table 3). An overview of the incidence of IBA in different time periods is shown in Figure 3.

Table 3.

Results of logistic binominal regression analysis of IBA incidence prior and during the strict COVID-lockdown per participating country. Odds ratios (OR) are shown which indicates the odds of acquiring IBA during the strict COVID-lockdown, using the odds of acquiring IBA prior to the COVID-lockdown as reference category. Colours represent a range of stringency index where green is the relatively highest and red the relatively lowest.

Figure 3.

Incidence of IBA prior (January 2015–March 2020) and during the lockdown (March 2020–June 2020) of countries where BA care is centralised. Incidence is expressed as number of IBA patients per 10,000 live births. Different symbols represent different countries and dashed lines represent countries, while the connected line represents overall incidence of all countries. Green lines indicate a decrease in IBA incidence from pre-lockdown to lockdown period, while a red line indicates an increase.

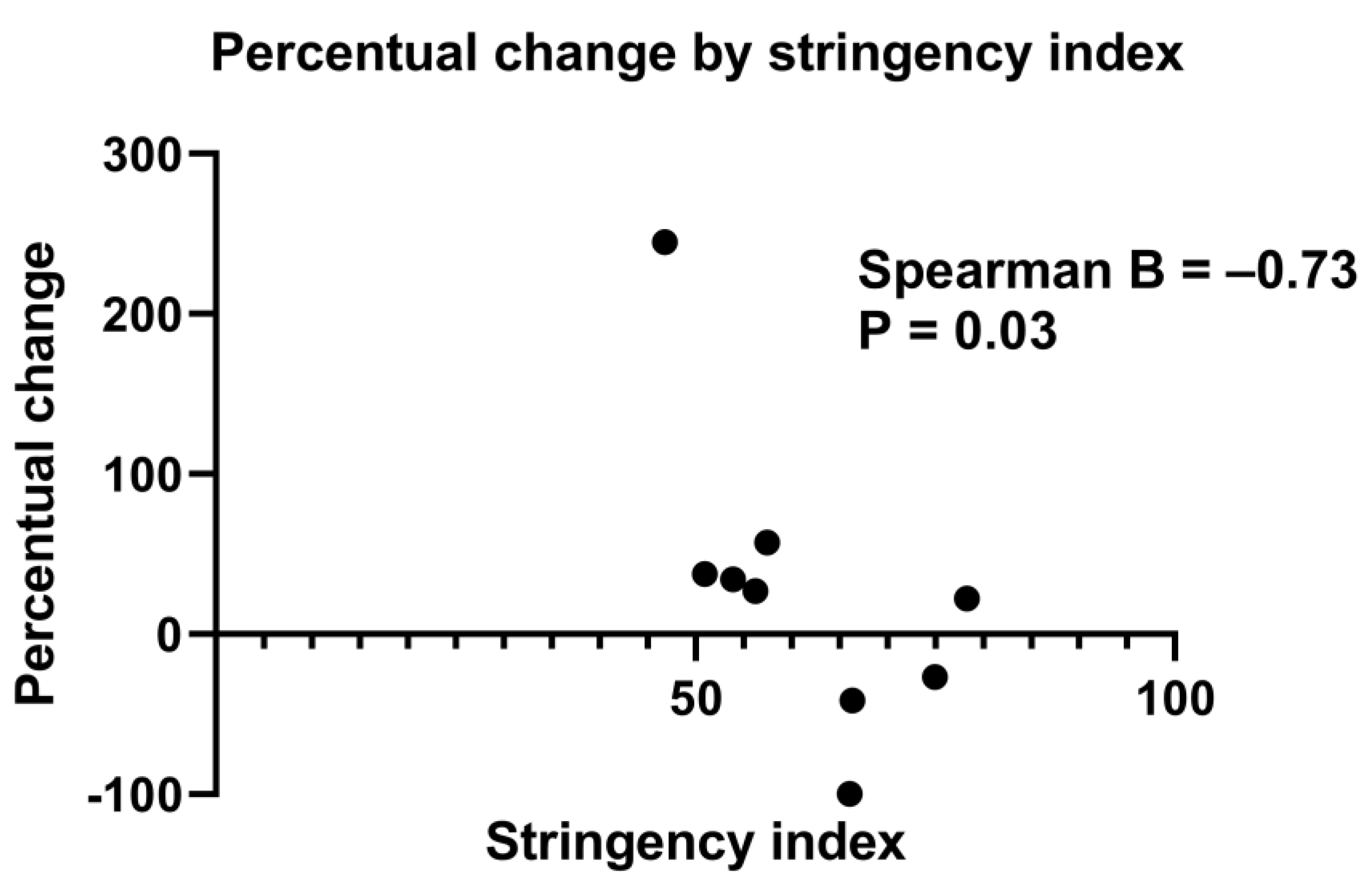

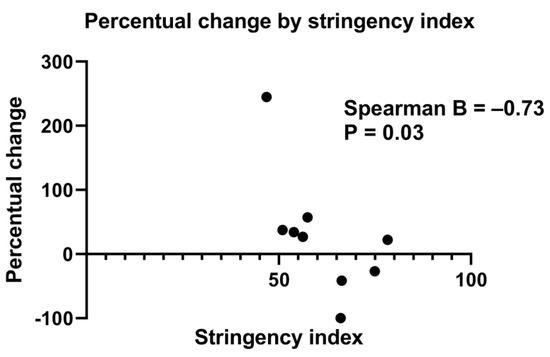

3.2. Association between Patients Acquiring IBA and Strictness of Lockdown

Table S1 shows the association between the SI and the percentage change of mean number of IBA patients born per month. When all centres were included, no statistically significant association was reached (B = −0.33, p = 0.31). Due to confounding factors in Padova and in Hannover (i.e., significant changes in referral patterns leading to more IBA patients being referred to the hospital than usual, and a steep increase in the number of cases), we also performed an analysis without the data of these centres. The association between the percentage change of mean number of IBA patients born per month per centre and SI then reached statistical significance (B = −0.73, p = 0.03) (Figure 4 and Table S1).

Figure 4.

Scatter plot showing the percentage change of mean IBA patients born per month (from pre-lockdown to lockdown period) for every stringency index of the participating centres. n = 9, Hannover and Padova were excluded (three centres from United Kingdom were merged into one). Spearman’s correlation coefficient = −0.73, p = 0.03.

For countries with national BA data only, Spearman’s correlation coefficient between percentage change of mean number of IBA patients born per month per centre and SI was −0.60 (p = 0.35). Logistic regression analysis yielded an OR of 0.99 (95% CI: 0.98–1.00, p = 0.25) per added SI point on IBA incidence during the period of the strict lockdown. For example, compared to the pre-lockdown period, the OR of acquiring IBA in the United Kingdom during the lockdown period was 0.65 (Table S2).

When IBA incidence during COVID lockdown was compared to the IBA incidence from 1 March–31 May from 2015 up to and including 2019, every 1-point increase in the SI decreased the odds of acquiring IBA; however, this was not statistically significant (OR: 0.996 [95% CI: 0.98–1.01, p = 0.54]). 62 (23%) IBA patients were included for this analysis.

3.3. Age at KPE

There was no significant difference in median age at KPE (51 vs. 53, p = 0.73) between the pre-lockdown period and lockdown period overall, or in countries with national and part of the national BA data (48 vs. 57, p = 0.29 and 58 vs. 53, p = 0.43, respectively, see Table 4).

Table 4.

Median age at Kasai portoenterostomy (KPE) during the pre-lockdown period (January 2015–March 2020) and lockdown period (March 2020–June 2020).

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate the incidence of IBA in various European countries before and during the COVID-issued lockdown in 2020. Furthermore, we aimed to investigate if the strictness of the lockdown had an effect on the change in IBA incidence from the pre-lockdown period to the period of strict lockdown. Our results indicated that overall, there was a variable change in the incidence of IBA during the COVID-issued lockdown in comparison to the period prior to the lockdown.

We observed a negative association between stringency index and the percentage change of mean IBA patients born per month per centre. This finding indicated that a stricter government issued COVID-lockdown in a country was accompanied by a simultaneous larger decrease or even absence of the birth of patients with IBA in the period in which this lockdown was issued.

These results should be interpreted with caution. Incidence most accurately displays how common a disease is. In our study, incidence could not be calculated in countries where complete national data were not included because a reliable population at risk (i.e., live births in a region or country) could not be determined. To include centres from countries with part of the national BA data, we deemed it justifiable to use an alternative method with the number of IBA patients born per month. This method was based on two assumptions: an equal number of live births per month (not true by definition) and a consistent referral pattern of first- and second-line healthcare.

A change in referral pattern can lead to an over- or underestimation of the number of BA patients. A change in referral pattern occurred in two centres and they were excluded from the analysis. There was no change in referral pattern in other countries with part of the national BA data.

Furthermore, to exclude unnoticed bias due to changes in referral pattern, we analysed the effect of the COVID lockdown on IBA incidence separately in countries with national BA data. We again observed a negative association between SI and mean number of IBA patients born per month as well as incidence. However, these observations failed to reach statistical significance. We therefore have to stress that although this study found a negative association between stringency index and the percentage change of mean IBA patients born per month per centre, our results should be interpreted with caution and our conclusion cannot be a final one due to the limitations of our used method.

Studies investigating the epidemiology of (I)BA in Europe and around the globe have been performed in different countries. Results were conflicting with regard to the existence of clustering in space or time of the birth of BA patients [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. Even in studies where clustering was observed, discrepancy existed in relation to the time of year in which BA clustered and whether BA clustered in rural or urban areas. Rarity of BA leads to epidemiological limitations, especially when most studies investigating clustering are not able to incorporate an explanatory variable for clustering in their analysis.

When most European countries went into a COVID lockdown, aiming to reduce transmission of COVID-19 infections in March 2020, it provided us with an ‘experiment’ on a European scale: a period of three months in which transmission of other infectious pathogens was also reduced during the lockdown in various countries, allowing us to investigate the effect of this reduction on BA incidence. This is one of the main strengths of our study. Furthermore, our study included data on BA patients from many different European countries, which in itself is a rarity in research on BA. However, in order to perform reliable epidemiological on BA epidemiology in Europe (or other international regions), complete national databases should preferably be used to include all BA patients and have a defined population at risk (i.e., live births). Furthermore, it would be of interest to investigate the relation between non-COVID infection rates in the population and incidence of IBA in Europe to further investigate an infectious aetiology of (I)BA.

During the lockdown, BA patients were diagnosed and treated later than before the lockdown due to logistic reasons which was illustrated by a higher age at KPE in our study, leading to a long absence of BA patients presenting to the hospital. By analysing the month of birth of patients who acquired IBA instead of the month of presentation, we negated any effect of late presentation on the analysis. However, this method assumed that the (viral) insult proposedly leading to IBA took place perinatally. The timing of the insult leading to the occurrence IBA is still unknown and the insult may occur prenatally [29]. For this study, however, we assumed the insult proposedly leading to IBA took place around the birth of the patient. Our results did not exclude a prenatal insult as cause for IBA.

Length of the lockdown was defined as a relative short time period of three months, in which few BA patients were born. We deemed this short period appropriate as extending the period would include the relaxation of restrictions, possibly confounding our data.

Developmental or genetic causes can also still very well be involved in the pathophysiology [9,30,31]. Furthermore, lockdown measures were primarily aimed to reduce transmission of air-borne viral particles, while infection via contaminated food or ingestion of a toxin such as biliatresone (known to cause BA in animals) may still have occurred despite a strict lockdown [32,33]. These factors should be kept in mind when interpreting our results.

Despite the limitations in this study, collaborative projects as these could aid in tackling the issue of the rarity of a disease in epidemiological, clinical and mechanistical studies, allowing for a greater number of included patients, thereby having more potential to unravel conundrums. It would be of interest to investigate BA incidence in the years after the COVID lockdown to evaluate the potential sustained consequences of an impactful lockdown on the incidence of (I)BA.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this collaborative study between thirteen European centres investigated the effect of the strict COVID lockdown that was issued in various countries throughout Europe from March 2020. We found an association between the percentage change of mean IBA patients born per month and SI, an index for lockdown strictness, indicating that a stricter COVID lockdown in a country was accompanied by a simultaneous larger decrease or even absence of patients born with IBA in the period in which the lockdown was issued. Our analysis was limited by assumptions and limited statistical power. Furthermore, in countries with complete national BA data the association between IBA incidence and SI failed to reach statistical significance. Our results should therefore be interpreted with caution. Our findings may suggest an environmental factor at play in the pathophysiology of IBA. We hope that this study, using the European Reference Network RARE-Liver, will be the starting point of future collaborative efforts to elucidate the pathophysiology of this rare disease.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jcm12030775/s1, Table S1: Spearman’s correlation coefficient between percentage change of IBA patients born per month and stringency index per country; Table S2: Results from multivariate logistic regression.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.N. and J.B.F.H.; methodology, M.N. and J.B.F.H.; formal analysis, M.N. and J.B.F.H.; investigation, M.N., N.K.A., P.B., J.L.M.B., M.C., V.B.C., L.D., M.D., B.F., L.H., M.H., L.S.J., R.H.d.K., O.M.-S., E.G.P.O., M.P.P., C.P., M.R., M.S., E.S., H.J.V., B.E.W. and J.B.F.H.; data curation, M.N., N.K.A., P.B., J.L.M.B., M.C., V.B.C., L.D., M.D., B.F., L.H., M.H., L.S.J., R.H.d.K., O.M.-S., E.G.P.O., M.P.P., C.P., M.R., E.S., H.J.V., B.E.W. and J.B.F.H.; resources, M.N., N.K.A., P.B., J.L.M.B., M.C., V.B.C., L.D., M.D., B.F., L.H., M.H., L.S.J., R.H.d.K., O.M.-S., E.G.P.O., M.P.P., C.P., M.R., M.S., E.S., H.J.V., B.E.W. and J.B.F.H.; data curation, M.N., N.K.A., P.B., J.L.M.B., M.C., V.B.C., L.D., M.D., B.F., L.H., M.H., L.S.J., R.H.d.K., O.M.-S., E.G.P.O., M.P.P., C.P., M.R., M.S., E.S., H.J.V., B.E.W. and J.B.F.H.; writing—original draft preparation, M.N., J.B.F.H.; writing—review and editing, N.K.A., P.B., J.L.M.B., M.C., V.B.C., L.D., M.D., B.F., L.H., M.H., L.S.J., R.H.d.K., O.M.-S., E.G.P.O., M.P.P., C.P., M.R., M.S., E.S., H.J.V., B.E.W. and J.B.F.H.; supervision, J.L.M.B., R.H.d.K., H.J.V. and J.B.F.H.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University Medical Center Groningen (2017/056).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived because the research study involved no more than minimal risk to the patient.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. El Moumni, surgeon and epidemiologist, for his aid with statistical analysis and X. Zhou, virologist, for her advice on handling virological data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mack, C.L.; Feldman, A.G.; Sokol, R.J. Clues to the Etiology of Bile Duct Injury in Biliary Atresia. Semin. Liver Dis. 2012, 32, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, J.L.; Davenport, M.; Kelly, D.A. Biliary atresia. Lancet 2009, 374, 1704–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, S.K.; Donnelly, B.; Temple, H.; Tiao, G.M. A Rotavirus-Induced Mouse Model to Study Biliary Atresia and Neonatal Cholestasis. Methods Mol. Biol. 2019, 1981, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Yu, J.; Zhang, R.; Yin, Y.; Ye, J.; Tan, L.; Xia, H. The Perinatal Infection of Cytomegalovirus Is an Important Etiology for Biliary Atresia in China. Clin. Pediatr. 2011, 51, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riepenhoff-Talty, M.; Gouvea, V.; Evans, M.J.; Svensson, L.; Hoffenberg, E.; Sokol, R.J.; Uhnoo, I.; Greenberg, S.J.; Schakel, K.; Zhaori, G.; et al. Detection of Group C Rotavirus in Infants with Extrahepatic Biliary Atresia. J. Infect. Dis. 1996, 174, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zani, A.; Quaglia, A.; Hadzić, N.; Zuckerman, M.; Davenport, M. Cytomegalovirus-associated biliary atresia: An aetiological and prognostic subgroup. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2015, 50, 1739–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischler, B.; Ehrnst, A.; Forsgren, M.; Örvell, C.; Nemeth, A. The Viral Association of Neonatal Cholestasis in Sweden: A Possible Link Between Cytomegalovirus Infection and Extrahepatic Biliary Atresia. J. Craniofacial Surg. 1998, 27, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischler, B.; Czubkowski, P.; Dezsofi, A.; Liliemark, U.; Socha, P.; Sokol, R.J.; Svensson, J.F.; Davenport, M. Incidence, Impact and Treatment of Ongoing CMV Infection in Patients with Biliary Atresia in Four European Centres. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, M.; Muntean, A.; Hadzic, N. Biliary Atresia: Clinical Phenotypes and Aetiological Heterogeneity. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 5675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohrabi, C.; Alsafi, Z.; O’Neill, N.; Khan, M.; Kerwan, A.; Al-Jabir, A.; Iosifidis, C.; Agha, R. World Health Organization declares global emergency: A review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19). Int. J. Surg. 2020, 76, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Advice for the Public. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public (accessed on 18 September 2020).

- Kurgat, E.K.; Sexton, J.D.; Garavito, F.; Reynolds, A.; Contreras, R.D.; Gerba, C.P.; Leslie, R.A.; Edmonds-Wilson, S.L.; Reynolds, K.A. Impact of a hygiene intervention on virus spread in an office building. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2019, 222, 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luangasanatip, N.; Hongsuwan, M.; Limmathurotsakul, D.; Lubell, Y.; Lee, A.S.; Harbarth, S.; Day, N.P.J.; Graves, N.; Cooper, B. Comparative efficacy of interventions to promote hand hygiene in hospital: Systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ 2015, 351, h3728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooiveld, M.; Hendriksen, J.; Korevaar, J. Wekelijkse Surveillance Cijfers [Internet]. Nivel Zorgregistraties Eerste Lijn. 2020. Available online: www.nivel.nl/surveillance (accessed on 18 September 2020).

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, T.; Angrist, N.; Goldszmidt, R.; Kira, B.; Petherick, A.; Phillips, T.; Webster, S.; Cameron-Blake, E.; Hallas, L.; Majumdar, S.; et al. A global panel database of pandemic policies (Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker). Nat. Hum. Behav. 2021, 5, 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, T.; Angrist, N.; Hale, A.J.; Kira, B.; Majumdar, S.; Petherick, A.; Phillips, T.; Sridhar, D.; Thompson, R.N.; Webster, S.; et al. Government responses and COVID-19 deaths: Global evidence across multiple pandemic waves. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0253116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livesey, E.; Borja, M.C.; Sharif, K.; Alizai, N.; McClean, P.; Kelly, D.; Hadzic, N.; Davenport, M. Epidemiology of biliary atresia in England and Wales (1999–2006). Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2009, 94, F451–F455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chardot, C.; Carton, M.; Spire-Bendelac, N.; Le Pommelet, C.; Golmard, J.-L.; Auvert, B. Epidemiology of biliary atresia in France: A national study 1986–96. J. Hepatol. 1999, 31, 1006–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nomden, M.; van Wessel, D.B.; Ioannou, S.; Verkade, H.J.; de Kleine, R.H.; Alizadeh, B.Z.; Bruggink, J.L.; Hulscher, J.B. A Higher Incidence of Isolated Biliary Atresia in Rural Areas: Results From an Epidemiological Study in The Netherlands. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2021, 72, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wildhaber, B.E.; Majno, P.; Mayr, J.; Zachariou, Z.; Hohlfeld, J.; Schwoebel, M.; Kistler, W.; Meuli, M.; Le Coultre, C.; Mentha, G.; et al. Biliary Atresia: Swiss National Study, 1994–2004. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2008, 46, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimenez-Rivera, C.; Jolin-Dahel, K.S.; Fortinsky, K.J.; Gozdyra, P.; Benchimol, E.I. International incidence and outcomes of biliary atresia. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2013, 56, 344–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreiber, R.A.; Harpavat, S.; Hulscher, J.B.F.; Wildhaber, B.E. Biliary Atresia in 2021: Epidemiology, Screening and Public Policy. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischler, B.; Haglund, B.; Hjern, A. A population-based study on the incidence and possible pre- and perinatal etiologic risk factors of biliary atresia. J. Pediatr. 2002, 141, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strickland, A.D.; Shannon, K. Studies in the etiology of extrahepatic biliary atresia: Time-space clustering. J. Pediatr. 1982, 100, 749–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.J.; Kim, J.W.; Moon, J.S.; Ko, J.S. Epidemiology of Biliary Atresia in Korea. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2017, 32, 656–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, P.W.; Bresee, J.S.; Olney, R.S.; James, L.M.; Khoury, M.J. Epidemiology of Biliary Atresia: A Population-based Study. Pediatrics 1997, 99, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caton, A.R.; Druschel, C.M.; McNutt, L.A. The epidemiology of extrahepatic biliary atresia in New York State, 1983–1998. Paediatr Perinat. Epidemiol. 2004, 18, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mysore, K.R.; Shneider, B.L.; Harpavat, S. Biliary Atresia as a Disease Starting In Utero: Implications for Treatment, Diagnosis, and Pathogenesis. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2019, 69, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, J.A. Potential etiologies of biliary atresia. Pediatr. Transplant. 2005, 9, 646–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilgore, A.; Mack, C.L. Update on investigations pertaining to the pathogenesis of biliary atresia. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2017, 33, 1233–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhan, Y.; Chen, G.; Shen, Z.; Zheng, S.; Dong, R. The synthetic toxin biliatresone causes biliary atresia in mice. Lab. Investig. 2020, 100, 1425–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullrich, A.; Schranz, M.; Rexroth, U.; Hamouda, O.; Schaade, L.; Diercke, M.; Boender, T.S. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated non-pharmaceutical interventions on other notifiable infectious diseases in Germany: An analysis of national surveillance data during week 1–2016—Week 32–2020. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2021, 6, 100103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).