Changes in Psychological Outcomes after Cessation of Full Mu Agonist Long-Term Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Intervention

2.3. Participants

2.4. Measures

2.5. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

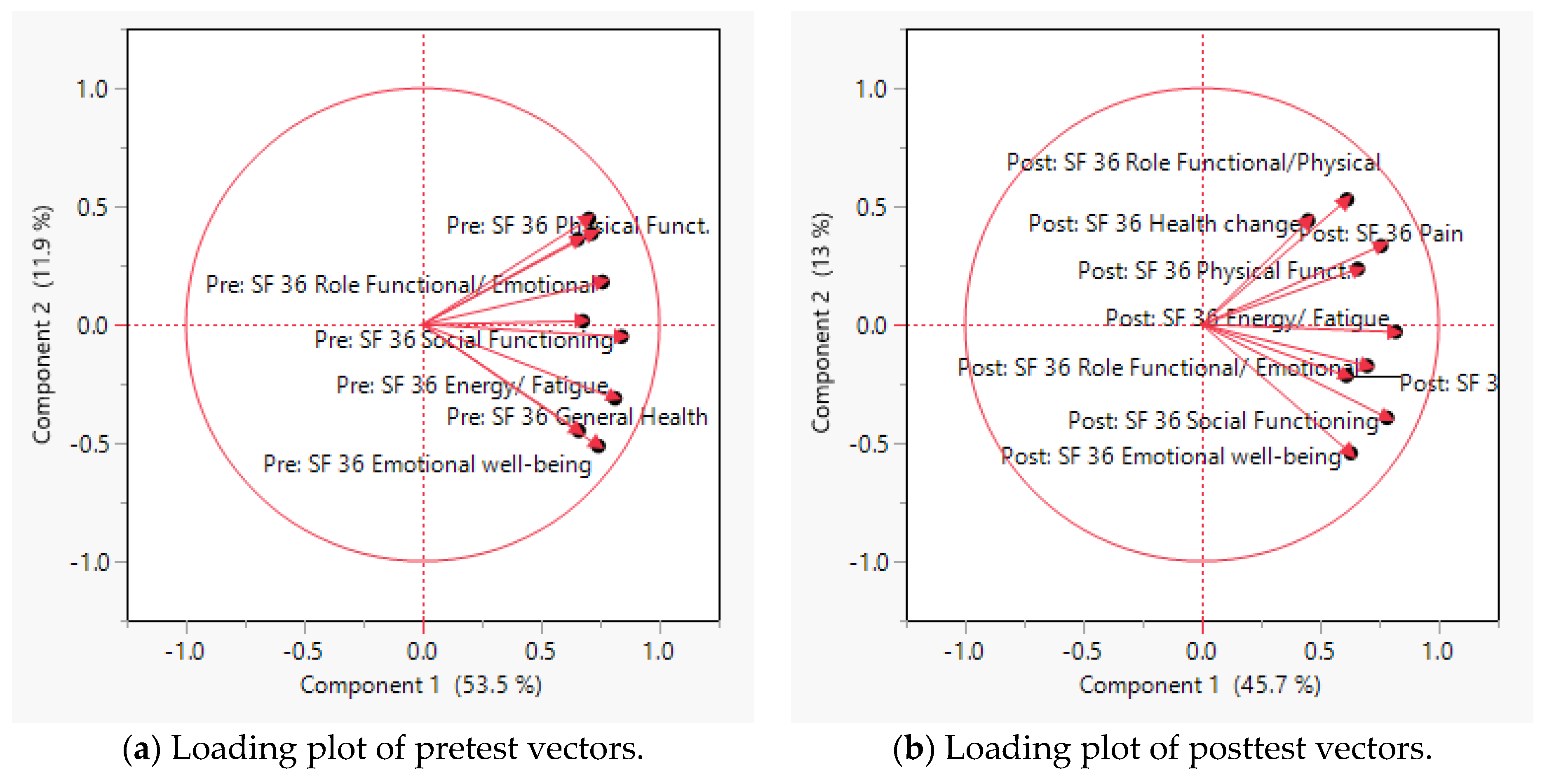

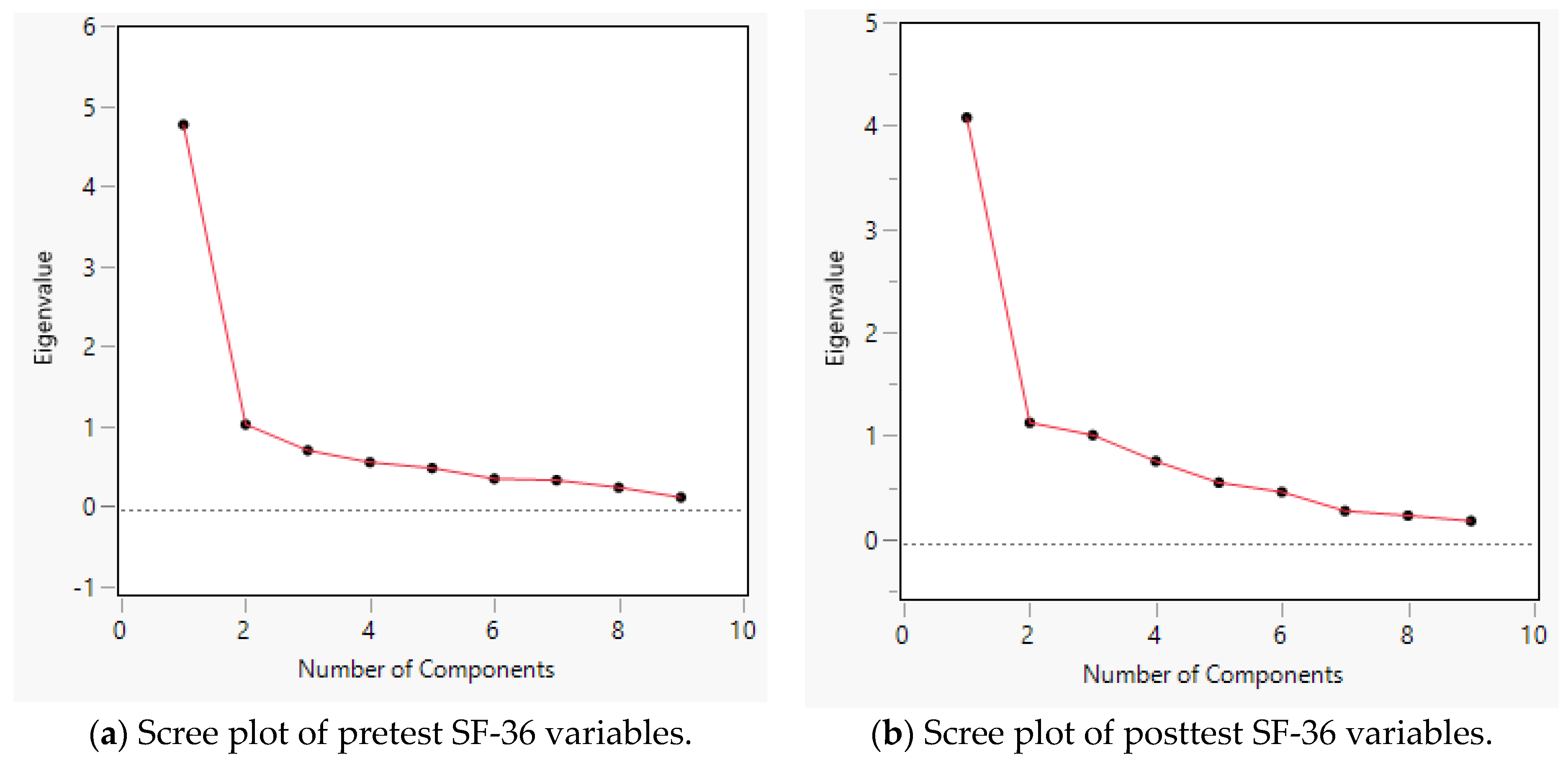

3.2. Principal Component Analysis and Scree Plot for the SF-36

3.3. Paired t-Tests

4. Discussion

4.1. Improved Psychological Assessment Scores Post-LTOT Cessation

4.2. Psychological Assessment Scores Lacking Significant Improvement Post-LTOT Cessation

4.3. Contribution to the Field

4.4. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dowell, D.; Haegerich, T.M.; Chou, R. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain—United States. MMWR Recomm. Rep. 2016, 65, 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Prescription Opioids DrugFacts. Available online: https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/prescription-opioids (accessed on 19 October 2020).

- Antony, T.; Alzaharani, S.Y.; El-Ghaiesh, S.H. Opioid-induced hypogonadism: Pathophysiology, clinical and therapeutics review. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2020, 47, 741–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenstein, T.K.; Rogers, T.J. Drugs of Abuse. In Neuroimmune Pharmacology; Ikezu, T., Gendelman, H.E., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 661–678. ISBN 978-3-319-44022-4. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, L.F.; Angst, M.S.; Clark, D. Opioid-induced hyperalgesia in humans: Molecular mechanisms and clinical considerations. Clin. J. Pain 2008, 24, 479–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.; Silverman, S.M.; Hansen, H.; Patel, V.B.; Manchikanti, L. A comprehensive review of opioid-induced hyperalgesia. Pain Physician 2011, 14, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radcliff, K.; Freedman, M.; Hilibrand, A.; Isaac, R.; Lurie, J.D.; Zhao, W.; Vaccaro, A.; Albert, T.; Weinstein, J. Does Opioid Pain Medication Use Affect the Outcome of Patients with Lumbar Disk Herniation? Spine 2013, 38, E849–E860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherrer, J.F.; Ahmedani, B.; Autio, K.; Debar, L.; Lustman, P.J.; Miller-Matero, L.R.; Salas, J.; Secrest, S.; Sullivan, M.D.; Wilson, L.; et al. The Prescription Opioids and Depression Pathways Cohort Study. J. Psychiatr. Brain Sci. 2020, 5, e200009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherrer, J.F.; Salas, J.; Schneider, F.D.; Bucholz, K.K.; Sullivan, M.D.; Copeland, L.A.; Ahmedani, B.K.; Burroughs, T.; Lustman, P.J. Characteristics of new depression diagnoses in patients with and without prior chronic opioid use. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 210, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmerhorst, G.T.T.; Vranceanu, A.-M.; Vrahas, M.; Smith, M.; Ring, D. Risk Factors for Continued Opioid Use One to Two Months After Surgery for Musculoskeletal Trauma. JBJS 2014, 96, 495–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grattan, A.; Sullivan, M.D.; Saunders, K.W.; Campbell, C.I.; Von Korff, M.R. Depression and Prescription Opioid Misuse among Chronic Opioid Therapy Recipients with No History of Substance Abuse. Ann. Fam. Med. 2012, 10, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arteta, J.; Cobos, B.; Hu, Y.; Jordan, K.; Howard, K. Evaluation of How Depression and Anxiety Mediate the Relationship between Pain Catastrophizing and Prescription Opioid Misuse in a Chronic Pain Population. Pain Med. 2016, 17, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martel, M.O.; Jamison, R.N.; Wasan, A.D.; Edwards, R.R. The Association Between Catastrophizing and Craving in Patients with Chronic Pain Prescribed Opioid Therapy: A Preliminary Analysis. Pain Med. 2014, 15, 1757–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.J.; Coffee, Z.; Yu, C.H.A.; Martel, M.O. Anxiety and Fear Avoidance Beliefs and Behavior May Be Significant Risk Factors for Chronic Opioid Analgesic Therapy Reliance for Patients with Chronic Pain—Results from a Preliminary Study. Pain Med. 2021, 22, 2106–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, S.S.; Fenton, M.C.; Keyes, K.M.; Blanco, C.; Zhu, H.; Storr, C.L. Mood/Anxiety disorders and their association with non-medical prescription opioid use and prescription opioid use disorder: Longitudinal evidence from the National Epidemiologic Study on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychol. Med. 2012, 42, 1261–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gros, D.F.; Milanak, M.E.; Brady, K.T.; Back, S.E. Frequency and Severity of Comorbid Mood and Anxiety Disorders in Prescription Opioid Dependence. Am. J. Addict. 2013, 22, 261–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manhapra, A.; Sullivan, M.D.; Ballantyne, J.C.; MacLean, R.R.; Becker, W.C. Complex Persistent Opioid Dependence with Long-term Opioids: A Gray Area That Needs Definition, Better Understanding, Treatment Guidance, and Policy Changes. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2020, 35, 964–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Process for Updating the Opioid Prescribing Guideline|CDC’s Response to the Opioid Overdose Epidemic|CDC. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/opioids/guideline-update/index.html (accessed on 25 February 2022).

- Oliva, E.M.; Bowe, T.; Manhapra, A.; Kertesz, S.; Hah, J.M.; Henderson, P.; Robinson, A.; Paik, M.; Sandbrink, F.; Gordon, A.J.; et al. Associations between stopping prescriptions for opioids, length of opioid treatment, and overdose or suicide deaths in US veterans: Observational evaluation. BMJ 2020, 368, m283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, J.R.; Scott, J.M.; Klein, J.W.; Jackson, S.; McKinney, C.; Novack, M.; Chew, L.; Merrill, J.O. Mortality After Discontinuation of Primary Care–Based Chronic Opioid Therapy for Pain: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2019, 34, 2749–2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark, T.L.; Parish, W. Opioid medication discontinuation and risk of adverse opioid-related health care events. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2019, 103, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutfy, K.; Cowan, A. Buprenorphine: A Unique Drug with Complex Pharmacology. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2004, 2, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahan, A.; Yassen, A.; Romberg, R.; Sarton, E.; Teppema, L.; Olofsen, E.; Danhof, M. Buprenorphine induces ceiling in respiratory depression but not in analgesia. Br. J. Anaesth. 2006, 96, 627–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Walsh, S.L.; Preston, K.L.; Stitzer, M.L.; Cone, E.J.; Bigelow, G.E. Clinical pharmacology of buprenorphine: Ceiling effects at high doses. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 1994, 55, 569–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oral-MME-CFs-vFeb-2018.pdf. Available online: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Prescription-Drug-Coverage/PrescriptionDrugCovContra/Downloads/Oral-MME-CFs-vFeb-2018.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2020).

- Gudin, J. A Narrative Pharmacological Review of Buprenorphine: A Unique Opioid for the Treatment of Chronic Pain. Pain Ther. 2020, 9, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.J.; Rubinstein, A. Continuous Perioperative Sublingual Buprenorphine. J. Pain Palliat. Care Pharmacother. 2016, 30, 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daitch, D.; Daitch, J.; Novinson, M.D.; Frey, M.; Mitnick, A.C.; Pergolizzi, J.J. Conversion from High-Dose Full-Opioid Agonists to Sublingual Buprenorphine Reduces Pain Scores and Improves Quality of Life for Chronic Pain Patients. Pain Med. 2014, 15, 2087–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlsson, M.; Berggren, A.-C. Efficacy and safety of low-dose transdermal buprenorphine patches (5, 10, and 20 microg/h) versus prolonged-release tramadol tablets (75, 100, 150, and 200 mg) in patients with chronic osteoarthritis pain: A 12-week, randomized, open-label, controlled, parallel-group noninferiority study. Clin. Ther. 2009, 31, 503–513. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, M.J.; Coffee, Z.; Yu, C.H. Prolonged Cessation of Chronic Opioid Analgesic Therapy: A Multidisciplinary Intervention. Am. J. Manag. Care 2022, 28, 60–65. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, M.J.; Coffee, Z.; Goza, J.; Rumrill, K. Microinduction to Buprenorphine from Methadone for Chronic Pain: Outpatient Protocol with Case Examples. J. Pain Palliat. Care Pharmacother. 2022, 36, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns, M.W. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: The Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep 1991, 14, 540–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, J.E.; Sherbourne, C.D. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med. Care 1992, 30, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.W.; Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddell, G.; Newton, M.; Henderson, I.; Somerville, D.; Main, C.J. A Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ) and the role of fear-avoidance beliefs in chronic low back pain and disability. Pain 1993, 52, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.P.; Kori, S.H.; Todd, D.D. The Tampa Scale: A Measure of Kinesiophobia. Clin. J. Pain 1991, 7, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, M.J.L.; Bishop, S.R.; Pivik, J. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale: Development and Validation. Psychol. Assess. 1995, 7, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BPI_UserGuide.pdf. Available online: https://www.mdanderson.org/documents/Departments-and-Divisions/Symptom-Research/BPI_UserGuide.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2020).

- George, S.Z.; Fritz, J.M.; Erhard, R.E. A comparison of fear-avoidance beliefs in patients with lumbar spine pain and cervical spine pain. Spine 2001, 26, 2139–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, H.; Ellis, T.; Stanish, W.D.; Sullivan, M.J.L. Psychosocial factors related to return to work following rehabilitation of whiplash injuries. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2007, 17, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PCSManual_English.pdf. Available online: http://sullivan-painresearch.mcgill.ca/pdf/pcs/PCSManual_English.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2020).

- Cleeland, C.S.; Ryan, K.M. Pain assessment: Global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Ann. Acad. Med. Singap. 1994, 23, 129–138. [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby, W.G. Statistical Graphics for Visualizing Multivariate Data; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, W.; Kang, M. GGE Biplot Analysis; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; White, I.R.; Carlin, J.B.; Spratt, M.; Royston, P.; Kenward, M.G.; Wood, A.M.; Carpenter, J.R. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: Potential and pitfalls. BMJ 2009, 338, b2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karp, J.F.; Butters, M.A.; Begley, A.; Miller, M.D.; Lenze, E.J.; Blumberger, D.; Mulsant, B.; Reynolds, C.F. Safety, Tolerability, and Clinical Effect of Low-Dose Buprenorphine for Treatment-Resistant Depression in Mid-Life and Older Adults. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2014, 75, e785–e793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, M.J.L.; Adams, H.; Rhodenizer, T.; Stanish, W.D. A psychosocial risk factor--targeted intervention for the prevention of chronic pain and disability following whiplash injury. Phys. Ther. 2006, 86, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, K.T.; Sinha, R. Co-occurring mental and substance use disorders: The neurobiological effects of chronic stress. Am. J. Psychiatry 2005, 162, 1483–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, M.M.; Emrich, H.M. Current and historical concepts of opiate treatment in psychiatric disorders. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 1988, 3, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, S.S.; Keyes, K.M.; Storr, C.L.; Zhu, H.; Chilcoat, H.D. Pathways between nonmedical opioid use/dependence and psychiatric disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009, 103, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Peciña, M.; Karp, J.F.; Mathew, S.; Todtenkopf, M.S.; Ehrich, E.W.; Zubieta, J.-K. Endogenous opioid system dysregulation in depression: Implications for new therapeutic approaches. Mol. Psychiatry 2019, 24, 576–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, S.E. Buprenorphine: An Analgesic with an Expanding Role in the Treatment of Opioid Addiction. CNS Drug Rev. 2002, 8, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidlack, J.M.; Knapp, B.I.; Deaver, D.R.; Plotnikava, M.; Arnelle, D.; Wonsey, A.M.; Toh, M.F.; Pin, S.S.; Namchuk, M.N. In Vitro Pharmacological Characterization of Buprenorphine, Samidorphan, and Combinations Being Developed as an Adjunctive Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2018, 367, 267–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafini, G.; Adavastro, G.; Canepa, G.; De Berardis, D.; Valchera, A.; Pompili, M.; Nasrallah, H.; Amore, M. The Efficacy of Buprenorphine in Major Depression, Treatment-Resistant Depression and Suicidal Behavior: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, J.; Jahromi, M.S. Anxiety Treatment of Opioid Dependent Patients with Buprenorphine: A Randomized, Double-blind, Clinical Trial. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2017, 39, 445–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubieta, J.-K.; Ketter, T.A.; Bueller, J.A.; Xu, Y.; Kilbourn, M.R.; Young, E.A.; Koeppe, R.A. Regulation of Human Affective Responses by Anterior Cingulate and Limbic µ-Opioid Neurotransmission. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2003, 60, 1145–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yovell, Y.; Bar, G.; Mashiah, M.; Baruch, Y.; Briskman, I.; Asherov, J.; Lotan, A.; Rigbi, A.; Panksepp, J. Ultra-Low-Dose Buprenorphine as a Time-Limited Treatment for Severe Suicidal Ideation: A Randomized Controlled Trial. AJP 2016, 173, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, A.; Brantl, V.; Herz, A.; Emrich, H.M. Psychotomimesis mediated by kappa opiate receptors. Science 1986, 233, 774–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenore, P.L. Psychotherapeutic Benefits of Opioid Agonist Therapy. J. Addict. Dis. 2008, 27, 49–65. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10550880802122646?journalCode=wjad20 (accessed on 3 February 2022). [CrossRef]

- Fritz, J.M.; George, S.Z. Identifying psychosocial variables in patients with acute work-related low back pain: The importance of fear-avoidance beliefs. Phys. Ther. 2002, 82, 973–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- George, S.Z.; Fritz, J.M.; Childs, J.D. Investigation of Elevated Fear-Avoidance Beliefs for Patients with Low Back Pain: A Secondary Analysis Involving Patients Enrolled in Physical Therapy Clinical Trials. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2008, 38, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, S.Z.; Fritz, J.M.; McNeil, D.W. Fear-avoidance beliefs as measured by the fear-avoidance beliefs questionnaire: Change in fear-avoidance beliefs questionnaire is predictive of change in self-report of disability and pain intensity for patients with acute low back pain. Clin. J. Pain 2006, 22, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlaeyen, J.W.; Linton, S.J. Fear-avoidance and its consequences in chronic musculoskeletal pain: A state of the art. Pain 2000, 85, 317–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linton, S.J.; Shaw, W.S. Impact of Psychological Factors in the Experience of Pain. Phys. Ther. 2011, 91, 700–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddell, G.; Somerville, D.; Henderson, I.; Newton, M. Objective clinical evaluation of physical impairment in chronic low back pain. Spine 1992, 17, 617–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philips, H.; Jahanshahi, M. The components of pain behaviour report. Behav. Res. Ther. 1986, 24, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, T.; Fritz, J.; Whitman, J.; Wainner, R.; Magel, J.; Rendeiro, D.; Butler, B.; Garber, M.; Allison, S. A clinical prediction rule for classifying patients with low back pain who demonstrate short-term improvement with spinal manipulation. Spine 2002, 27, 2835–2843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleland, J.A.; Fritz, J.M.; Brennan, G.P. Predictive validity of initial fear avoidance beliefs in patients with low back pain receiving physical therapy: Is the FABQ a useful screening tool for identifying patients at risk for a poor recovery? Eur. Spine J. 2008, 17, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassamal, S.; Miotto, K.; Wang, T.; Saxon, A.J. A narrative review: The effects of opioids on sleep disordered breathing in chronic pain patients and methadone maintained patients. Am. J. Addict. 2016, 25, 452–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correa, D.; Farney, R.J.; Chung, F.; Prasad, A.; Lam, D.; Wong, J. Chronic opioid use and central sleep apnea: A review of the prevalence, mechanisms, and perioperative considerations. Anesth. Analg. 2015, 120, 1273–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Teichtahl, H.; Goodman, C.; Drummer, O.; Grunstein, R.R.; Kronborg, I. Subjective Daytime Sleepiness and Daytime Function in Patients on Stable Methadone Maintenance Treatment: Possible Mechanisms. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2008, 4, 557–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calley, D.Q.; Jackson, S.; Collins, H.; George, S.Z. Identifying Patient Fear-Avoidance Beliefs by Physical Therapists Managing Patients with Low Back Pain. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2010, 40, 774–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, A.K.; Waddell, G.; Tillotson, K.M.; Summerton, N. Information and advice to patients with back pain can have a positive effect. A randomized controlled trial of a novel educational booklet in primary care. Spine 1999, 24, 2484–2491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Questionnaire | Application |

|---|---|

| Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) [32] | Measures daytime sleepiness: 0 to 10 is normal; 11–12 is mild; 13–15 is moderate excessive; and 16–24 is severe excessive. |

| The 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36) [33] | A total of 8 categories are scored on a scale from 0 to 100, with 100 representing the highest level of functioning possible: physical functioning, bodily pain, role limitations due to physical health problems, role limitations due to personal or emotional problems, emotional well-being, social functioning, energy/fatigue, and general health perceptions. |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-Item Scale (GAD-7) [34] | Assesses anxiety: 0–5 is mild, 6–10 is moderate, and 11–15 is high. |

| Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) [35] | Assesses depression: 1–4 is minimal, 5–9 is mild, 10–14 is moderate, 15–19 is moderately severe, and 20–27 is severe. |

| Fear Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire—Work and Physical Activity (FAB-Wand PA) [14,36,40] | Two subscales (FAB-W: 0-42; FAB-PA 0-24) in which higher scores indicate more severe pain and disability due to fear avoidance beliefs about work and physical activity. Various score thresholds have been documented as associated with clinical relevancy and specific negative chronicity of CNCP. Higher scores have been associated with poor physical and manual therapy results and low return to work rates after an injury. |

| Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia (TKS) [37] | A measure of fear of movement and reinjury. Scores range from 17–68, with higher scores being of higher severity. |

| Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) [14,38,41,42] | Assesses levels of catastrophizing. In initial validation, a score of 30 or more correlated with high unemployment, self-declared “total” disability, and clinical depression. However, various lower score thresholds have been documented as associated with clinical relevancy for specific negative chronicity of CNCP. |

| Brief Pain Inventory-Severity and Impairment (BPI-Pain and Impairment) [39,43] | Provides two scores which assess the severity of pain and pain-related impairment on daily functions using the mean of several Likert scales of 0–10, with 10 being the worst. |

| Variable | Pretest Mean | Posttest Mean | Std. Error | n | t-Ratio | p | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF-36 | 36.95 | 49.76 | 2.41 | 64 | 5.31 | <0.0001 * | 7.99 | 17.62 |

| ESS | 8.08 | 8.47 | 0.46 | 61 | 0.84 | 0.4058 | −0.54 | 1.31 |

| PHQ | 11.82 | 7.91 | 0.81 | 57 | −4.80 | <0.0001 * | −5.53 | −2.29 |

| GAD7 | 7.71 | 7.43 | 0.94 | 58 | −0.29 | 0.7692 | −2.15 | 1.60 |

| BPI-Pain | 5.91 | 4.67 | 0.20 | 58 | −6.19 | <0.0001 * | −1.65 | −0.84 |

| BPI-Impairment | 6.35 | 4.56 | 0.30 | 60 | −5.88 | <0.0001 * | −2.39 | −1.18 |

| PCS | 21.6 | 13.32 | 1.39 | 56 | −5.92 | <0.0001 * | −11.09 | −5.48 |

| FAB-PA | 12.95 | 11.18 | 1.03 | 55 | −1.71 | <0.0001 * | −3.83 | 0.31 |

| FAB-W | 24.02 | 23.8 | 1.31 | 45 | −0.14 | 0.8867 | −3.01 | 1.39 |

| TSK | 35.72 | 35.16 | 1.42 | 34 | 0.39 | 0.6967 | −3.39 | 2.29 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Silva, M.J.; Coffee, Z.; Yu, C.H.A.; Hu, J. Changes in Psychological Outcomes after Cessation of Full Mu Agonist Long-Term Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1354. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12041354

Silva MJ, Coffee Z, Yu CHA, Hu J. Changes in Psychological Outcomes after Cessation of Full Mu Agonist Long-Term Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(4):1354. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12041354

Chicago/Turabian StyleSilva, Marcelina Jasmine, Zhanette Coffee, Chong Ho Alex Yu, and Joshua Hu. 2023. "Changes in Psychological Outcomes after Cessation of Full Mu Agonist Long-Term Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 4: 1354. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12041354

APA StyleSilva, M. J., Coffee, Z., Yu, C. H. A., & Hu, J. (2023). Changes in Psychological Outcomes after Cessation of Full Mu Agonist Long-Term Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(4), 1354. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12041354