Next-Generation Sequencing in Critically Ill COVID-19 Patients with Suspected Bloodstream Infections: A Retrospective Cohort Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting and Patients

2.2. Blood Cultures

2.3. Next-Generation Sequencing

2.4. Virology

2.5. Data Collection

2.6. Data Review

2.7. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

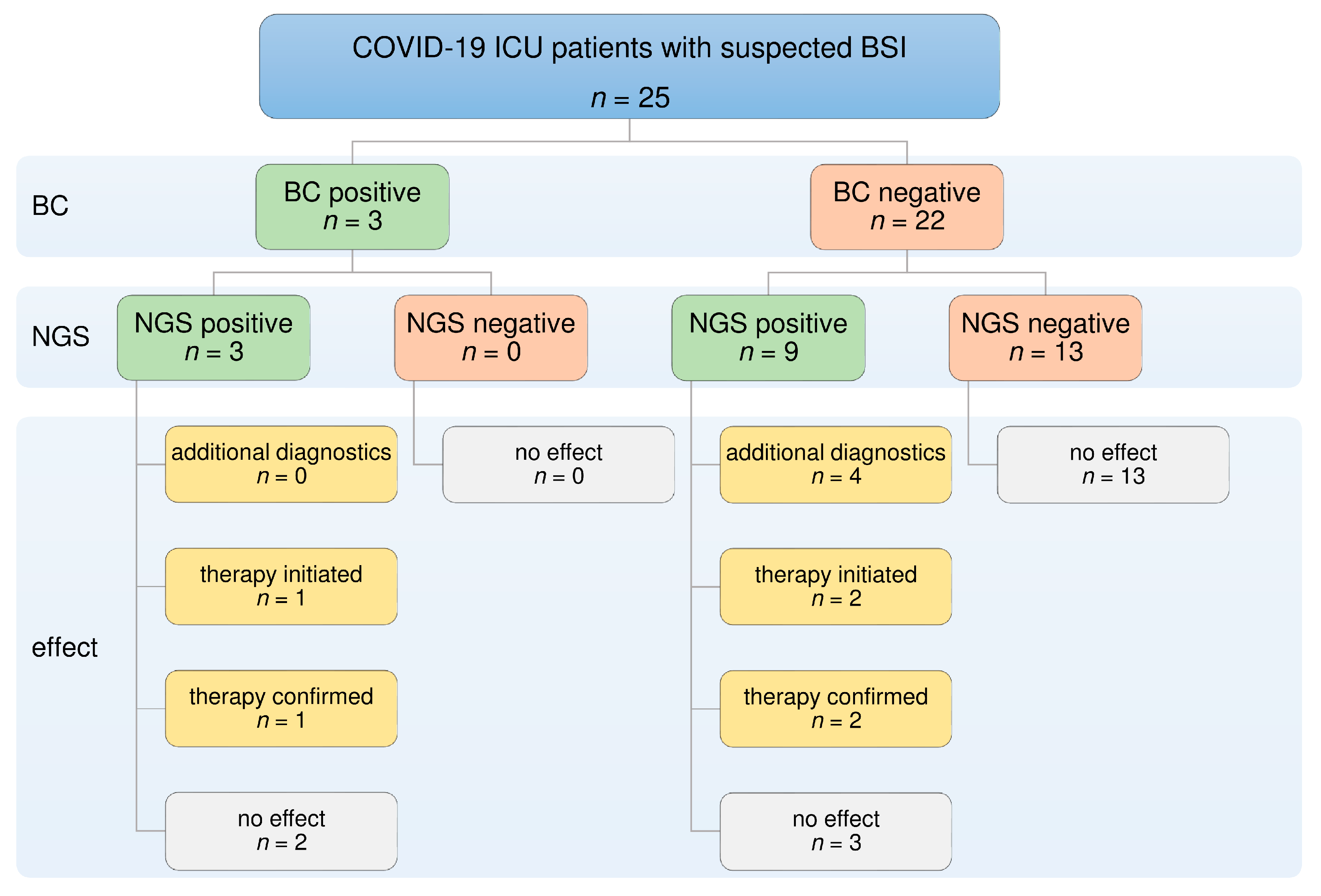

3.2. NGS and BC Results

3.3. Direct Comparison of NGS and BC

3.4. Diagnostic Benefit of NGS

3.5. Additional Viral Diagnostic

3.6. Antimicrobial Therapy

- (1)

- Aciclovir was administered in two patients following positive NGS results for HSV-1, with confirmation by PCR.

- (2)

- Vancomycin treatment was started in two patients after the detection of E. faecium by NGS.

4. Discussion

4.1. Confirmation of Positive BC Results by NGS

4.2. Defining Antimicrobial Therapy Using NGS

4.3. Contamination

4.4. Value of NGS in the Diagnosis of Fungal Infections

4.5. Value of NGS in the Diagnosis of Viral Infections

4.6. Methodological Characteristics and Limitations of NGS

4.7. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Asch, D.A.; Sheils, N.E.; Islam, N.; Chen, Y.; Werner, R.M.; Buresh, J.; Doshi, J.A. Variation in US Hospital Mortality Rates for Patients Admitted With COVID-19 During the First 6 Months of the Pandemic. JAMA Intern. Med. 2021, 181, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horwitz, L.I.; Jones, S.A.; Cerfolio, R.J.; Francois, F.; Greco, J.; Rudy, B.; Petrilli, C.M. Trends in COVID-19 Risk-Adjusted Mortality Rates. J. Hosp. Med. 2020, 16, 90–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigal, A.; Milo, R.; Jassat, W. Estimating disease severity of Omicron and Delta SARS-CoV-2 infections. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2022, 22, 267–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anesi, G.L.; Jablonski, D.J.; Harhay, M.O.; Atkins, J.H.; Bajaj, J.; Baston, C.; Brennan, P.J.; Candeloro, C.L.; Catalano, L.M.; Cereda, M.F.; et al. Characteristics, Outcomes, and Trends of Patients with COVID-19–Related Critical Illness at a Learning Health System in the United States. Ann. Intern. Med. 2021, 174, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagiannidis, C.; Windisch, W.; McAuley, D.F.; Welte, T.; Busse, R. Major differences in ICU admissions during the first and second COVID-19 wave in Germany. Lancet Respir. Med. 2021, 9, e47–e48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contou, D.; Fraissé, M.; Pajot, O.; Tirolien, J.-A.; Mentec, H.; Plantefève, G. Comparison between first and second wave among critically ill COVID-19 patients admitted to a French ICU: No prognostic improvement during the second wave? Crit. Care 2021, 25, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Santis, V.; Corona, A.; Vitale, D.; Nencini, C.; Potalivo, A.; Prete, A.; Zani, G.; Malfatto, A.; Tritapepe, L.; Taddei, S.; et al. Bacterial infections in critically ill patients with SARS-2-COVID-19 infection: Results of a prospective observational multicenter study. Infection 2021, 50, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.; Lima, C.; Magalhães, V.; Baltazar, L.; Peres, N.; Caligiorne, R.; Moura, A.; Fereguetti, T.; Martins, J.; Rabelo, L.; et al. Fungal and bacterial coinfections increase mortality of severely ill COVID-19 patients. J. Hosp. Infect. 2021, 113, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafran, N.; Shafran, I.; Ben-Zvi, H.; Sofer, S.; Sheena, L.; Krause, I.; Shlomai, A.; Goldberg, E.; Sklan, E.H. Secondary bacterial infection in COVID-19 patients is a stronger predictor for death compared to influenza patients. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrer, R.; Martin-Loeches, I.; Phillips, G.; Osborn, T.M.; Townsend, S.; Dellinger, R.P.; Artigas, A.; Schorr, C.; Levy, M.M. Empiric Antibiotic Treatment Reduces Mortality in Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock From the First Hour. Crit. Care Med. 2014, 42, 1749–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liu, V.X.; Fielding-Singh, V.; Greene, J.D.; Baker, J.M.; Iwashyna, T.J.; Bhattacharya, J.; Escobar, G.J. The Timing of Early Antibiotics and Hospital Mortality in Sepsis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 196, 856–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokota, P.K.O.; Marra, A.R.; Martino, M.D.V.; Victor, E.S.; Durão, M.S.; Edmond, M.; Dos Santos, O.F.P. Impact of Appropriate Antimicrobial Therapy for Patients with Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock—A Quality Improvement Study. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e104475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grumaz, S.; Grumaz, C.; Vainshtein, Y.; Stevens, P.; Glanz, K.; Decker, S.O.; Hofer, S.; Weigand, M.A.; Brenner, T.; Sohn, K. Enhanced Performance of Next-Generation Sequencing Diagnostics Compared With Standard of Care Microbiological Diagnostics in Patients Suffering From Septic Shock. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 47, e394–e402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, R.P.; Keller, P.M.; Baier, M.; Hagel, S.; Pletz, M.W.; Brunkhorst, F.M. Quality of blood culture testing—A survey in intensive care units and microbiological laboratories across four European countries. Crit. Care 2013, 17, R248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, J.-L.; Brealey, D.; Libert, N.; Abidi, N.E.; O’Dwyer, M.; Zacharowski, K.; Mikaszewska-Sokolewicz, M.; Schrenzel, J.; Simon, F.; Wilks, M.; et al. Rapid Diagnosis of Infection in the Critically Ill, a Multicenter Study of Molecular Detection in Bloodstream Infections, Pneumonia, and Sterile Site Infections. Crit. Care Med. 2015, 43, 2283–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timsit, J.-F.; Ruppé, E.; Barbier, F.; Tabah, A.; Bassetti, M. Bloodstream infections in critically ill patients: An expert statement. Intensiv. Care Med. 2020, 46, 266–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Gong, Y.; Sun, R.; Su, L.; Lin, X.; Shen, A.; Zhou, J.; Caiji, Z.; Wang, X.; et al. Diagnosis of Sepsis with Cell-free DNA by Next-Generation Sequencing Technology in ICU Patients. Arch. Med. Res. 2016, 47, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Ren, D.; Ren, C.; Yao, R.; Zhang, L.; Liang, X.; Li, G.; Wang, J.; Meng, X.; Liu, J.; Ye, Y.; et al. The microbiological diagnostic performance of metagenomic next-generation sequencing in patients with sepsis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grumaz, S.; Stevens, P.; Grumaz, C.; Decker, S.O.; Weigand, M.A.; Hofer, S.; Brenner, T.; von Haeseler, A.; Sohn, K. Next-generation sequencing diagnostics of bacteremia in septic patients. Genome Med. 2016, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kattner, S.; Herbstreit, F.; Schmidt, K.; Stevens, P.; Grumaz, S.; Dubler, S.; Rath, P.-M.; Brenner, T. Next-Generation Sequencing–Based Decision Support for Intensivists in Difficult-to-Diagnose Disease States: A Case Report of Invasive Cerebral Aspergillosis. A&A Pr. 2021, 15, e01447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehren, K.; Meißner, A.; Jazmati, N.; Wille, J.; Jung, N.; Vehreschild, J.J.; Hellmich, M.; Seifert, H. Clinical Impact of Rapid Species Identification From Positive Blood Cultures With Same-day Phenotypic Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing on the Management and Outcome of Bloodstream Infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2019, 70, 1285–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, T.; Skarabis, A.; Stevens, P.; Axnick, J.; Haug, P.; Grumaz, S.; Bruckner, T.; Luntz, S.; Witzke, O.; Pletz, M.W.; et al. Optimization of sepsis therapy based on patient-specific digital precision diagnostics using next generation sequencing (DigiSep-Trial)—Study protocol for a randomized, controlled, interventional, open-label, multicenter trial. Trials 2021, 22, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grumaz, C.; Hoffmann, A.; Vainshtein, Y.; Kopp, M.; Grumaz, S.; Stevens, P.; Decker, S.O.; Weigand, M.A.; Hofer, S.; Brenner, T.; et al. Rapid Next-Generation Sequencing–Based Diagnostics of Bacteremia in Septic Patients. J. Mol. Diagn. 2020, 22, 405–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decker, S.O.; Sigl, A.; Grumaz, C.; Stevens, P.; Vainshtein, Y.; Zimmermann, S.; Weigand, M.A.; Hofer, S.; Sohn, K.; Brenner, T. Immune-Response Patterns and Next Generation Sequencing Diagnostics for the Detection of Mycoses in Patients with Septic Shock—Results of a Combined Clinical and Experimental Investigation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, K.K.; Lyman, J.A. Updated Review of Blood Culture Contamination. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2006, 19, 788–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doern, G.V.; Carroll, K.C.; Diekema, D.J.; Garey, K.W.; Rupp, M.E.; Weinstein, M.P.; Sexton, D.J. Practical Guidance for Clinical Microbiology Laboratories: A Comprehensive Update on the Problem of Blood Culture Contamination and a Discussion of Methods for Addressing the Problem. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2019, 33, e00009-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacchetti, B.; Travis, J.; Steed, L.L.; Webb, G. Effects of COVID-19 on Blood Culture Contamination at a Tertiary Care Academic Medical Center. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e00277-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Self, W.H.; Speroff, T.; Grijalva, C.G.; McNaughton, C.D.; Ashburn, J.; Liu, D.; Arbogast, P.G.; Russ, S.; Storrow, A.B.; Talbot, T.R. Reducing Blood Culture Contamination in the Emergency Department: An Interrupted Time Series Quality Improvement Study. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2013, 20, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, E.; Bolondi, G.; Gamberini, E.; Santonastaso, D.P.; Circelli, A.; Spiga, M.; Sambri, V.; Agnoletti, V. Increased blood culture contamination rate during COVID-19 outbreak in intensive care unit: A brief report from a single-centre. J. Intensiv. Care Soc. 2021, 23, 500–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, D.; Ininbergs, K.; Hedman, K.; Giske, C.G.; Strålin, K.; Özenci, V. Low prevalence of bloodstream infection and high blood culture contamination rates in patients with COVID-19. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0242533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gangneux, J.-P.; Dannaoui, E.; Fekkar, A.; Luyt, C.-E.; Botterel, F.; De Prost, N.; Tadié, J.-M.; Reizine, F.; Houzé, S.; Timsit, J.-F.; et al. Fungal infections in mechanically ventilated patients with COVID-19 during the first wave: The French multicentre MYCOVID study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2021, 10, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehler, P.; Cornely, O.A.; Böttiger, B.W.; Dusse, F.; Eichenauer, D.A.; Fuchs, F.; Hallek, M.; Jung, N.; Klein, F.; Persigehl, T.; et al. COVID-19 associated pulmonary aspergillosis. Mycoses 2020, 63, 528–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alanio, A.; Dellière, S.; Fodil, S.; Bretagne, S.; Mégarbane, B. Prevalence of putative invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020, 8, e48–e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verweij, P.E.; Rijnders, B.J.A.; Brüggemann, R.J.M.; Azoulay, E.; Bassetti, M.; Blot, S.; Calandra, T.; Clancy, C.J.; Cornely, O.A.; Chiller, T.; et al. Review of influenza-associated pulmonary aspergillosis in ICU patients and proposal for a case definition: An expert opinion. Intensive Care Med. 2020, 46, 1524–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, M.; Estévez, A.; Sánchez-Carrillo, C.; Guinea, J.; Escribano, P.; Alonso, R.; Valerio, M.; Padilla, B.; Bouza, E.; Muñoz, P. Incidence of Candidemia Is Higher in COVID-19 versus Non-COVID-19 Patients, but Not Driven by Intrahospital Transmission. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macauley, P.; Epelbaum, O. Epidemiology and Mycology of Candidaemia in non-oncological medical intensive care unit patients in a tertiary center in the United States: Overall analysis and comparison between non-COVID-19 and COVID-19 cases. Mycoses 2021, 64, 634–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, P.G.; Kauffman, C.A.; Andes, D.R.; Clancy, C.J.; Marr, K.A.; Ostrosky-Zeichner, L.; Reboli, A.C.; Schuster, M.G.; Vazquez, J.A.; Walsh, T.J.; et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Candidiasis: 2016 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 62, e1–e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walton, A.; Muenzer, J.T.; Rasche, D.; Boomer, J.S.; Sato, B.; Brownstein, B.H.; Pachot, A.; Brooks, T.L.; Deych, E.; Shannon, W.D.; et al. Reactivation of Multiple Viruses in Patients with Sepsis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e98819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, A.; Buetti, N.; Houhou-Fidouh, N.; Patrier, J.; Abdel-Nabey, M.; Jaquet, P.; Presente, S.; Girard, T.; Sayagh, F.; Ruckly, S.; et al. HSV-1 reactivation is associated with an increased risk of mortality and pneumonia in critically ill COVID-19 patients. Crit. Care 2021, 25, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saade, A.; Moratelli, G.; Azoulay, E.; Darmon, M. Herpesvirus reactivation during severe COVID-19 and high rate of immune defect. Infect. Dis. Now 2021, 51, 676–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuest, K.E.; Erber, J.; Berg-Johnson, W.; Heim, M.; Hoffmann, D.; Kapfer, B.; Kriescher, S.; Ulm, B.; Schmid, R.M.; Rasch, S.; et al. Risk factors for Herpes simplex virus and Cytomegalovirus infections in critically-ill COVID-19 patients. Multidiscip. Respir. Med. 2022, 17, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonnet, A.; Engelmann, I.; Moreau, A.-S.; Garcia, B.; Six, S.; El Kalioubie, A.; Robriquet, L.; Hober, D.; Jourdain, M. High incidence of Epstein–Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, and human-herpes virus-6 reactivations in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Infect. Dis. Now 2021, 51, 296–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, J.; Yue, S.; Xue, W. Herpes simplex and herpes zoster viruses in COVID-19 patients. Ir. J. Med Sci. 2021, 191, 1093–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagel, S.; Scherag, A.; Schuierer, L.; Hoffmann, R.; Luyt, C.-E.; Pletz, M.W.; Kesselmeier, M.; Weis, S. Effect of antiviral therapy on the outcomes of mechanically ventilated patients with herpes simplex virus detected in the respiratory tract: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Care 2020, 24, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luyt, C.-E.; Combes, A.; Deback, C.; Aubriot-Lorton, M.-H.; Nieszkowska, A.; Trouillet, J.-L.; Capron, F.; Agut, H.; Gibert, C.; Chastre, J. Herpes Simplex Virus Lung Infection in Patients Undergoing Prolonged Mechanical Ventilation. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2007, 175, 935–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Total (n = 25) | NGS | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive (n = 13) | Negative (n = 12) | |||

| Age (years) | 70.0 (56.5–76.5) | 75.0 (70.0–78.5) | 59.5 (49.5–71.5) | 0.03 |

| Male sex | 16 (64) | 8 (62) | 8 (67) | 1 |

| Admission source | ||||

| Emergency room | 11 (44) | 6 (46) | 5 (42) | 0.82 |

| General hospital ward | 7 (28) | 4 (31) | 4 (33) | 0.67 |

| Intermediate care unit | 1 (4) | - | 1 (8) | 0.48 |

| Intensive care unit | 6 (24) | 3 (23) | 2 (17) | 0.65 |

| ICU stay (days) | 20.0 (11.0–33.5) | 22.0 (11.0–44.5) | 20.0 (11.3–29.0) | 0.61 |

| Mechanical ventilation (days) | 13.0 (8.5–27.0) | 18.0 (9.0–39.0) | 12.0 (4.75–21.3) | 0.34 |

| In-hospital death | 16 (64) | 9 (69) | 7 (58) | 0.69 |

| Comorbid conditions | ||||

| Arterial hypertension | 18 (72) | 10 (77) | 8 (67) | 0.67 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 14 (56) | 10 (77) | 4 (33) | 0.03 |

| Pulmonary disease | 4 (16) | 3 (23) | 1 (8) | 0.59 |

| Renal disease | 3 (12) | 2 (15) | 1 (8) | 1 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 5 (20) | 3 (23) | 2 (17) | 1 |

| Status at sampling | ||||

| SOFA-Score | 8.0 (6.5–10.5) | 9.00 (6.0–11.5) | 7.50 (6.3–8.0) | 0.43 |

| Ventilation | ||||

| Oxygen support | 8 (32) | 2 (15) | 6 (50) | 0.10 |

| Non-invasive ventilation | 4 (16) | 2 (15) | 2 (17) | 1 |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | 13 (52) | 9 (69) | 4 (33) | 0.07 |

| Oxygenation (paO2/FiO2, mmHg) | 144.0 (94.5–183) | 144.0 (103–195) | 144.0 (87.8–184) | 0.74 |

| Vasopressor therapy | 22 (88) | 12 (92) | 10 (83) | 0.59 |

| Renal replacement therapy | 8 (32) | 6 (46) | 2 (17) | 0.20 |

| Antimicrobial therapy | 13 (52) | 8 (62) | 5 (42) | 0.32 |

| Laboratory values | ||||

| Leucocytes (109/L) | 12.4 (8.36–16.5) | 12.2 (8.71–18.1) | 12.48 (8.27–15.4) | 1 |

| Neutrophils (109/L) | 8.13 (7.20–14.6) | 8.13 (7.57–14.8) | 9.430 (5.74–13.8) | 0.74 |

| Lymphocytes (109/L) | 0.63 (0.46–1.33) | 0.72 (0.48–1.60) | 0.62 (0.42–1.09) | 0.36 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 154 (82.2–219) | 130 (66.9–203) | 164 (120–252) | 0.25 |

| PCT (µg/L) | 1.00 (0.40–3.60) | 2.20 (0.45–5.45) | 0.50 (0.23–1.38) | 0.07 |

| IL-6 (ng/L) | 82.0 (35.0–686) | 109 (35.0–686) | 76.0 (34.0–869) | 0.87 |

| Microorganism | NGS (n = 25) | BC (n = 25) |

|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | 14 | 8 |

| Enterococcus faecium | 4 | 1 |

| Escherichia coli | 2 | 1 |

| Enterococcus raffinosus | 1 | - |

| Serratia marcescens | 1 | - |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 1 | - |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 1 | - |

| Helicobacter pylori | 1 | - |

| Bacteroides fragilis | 1 | - |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis† | - | 1 |

| considered as contaminant | ||

| Staphylococcus epidermidis† | - | 3 |

| Corynebacterium imitans | 1 | - |

| Xanthomonas campestris | 1 | - |

| Staphylococcus hominis† | - | 1 |

| Staphylococcus capitis† | - | 1 |

| Fungi | 1 | - |

| Candida parapsilosis | 1 | - |

| NGS (n = 25) | PCR (n = 4) | |

| Viruses | 8 | 6 |

| Epstein–Barr virus | 4 | 2 |

| Herpes simplex virus type 1 | 2 | 4 |

| Cytomegalovirus | 2 | - |

| ID | Age/Sex | (Suspected) Source of Infection | Diagnostic Method | Antimicrobial Therapy | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NGS | BC | Other | Empiric | Contribution of NGS | |||

| N3 | 79/f | Pulmonary | X. campestris, HSV-1 | Negative | Serum (PCR): HSV-1 | Meropenem | Initiation of aciclovir treatment |

| N8 | 70/m | Pulmonary | B. fragilis, EBV | Negative | Serum (PCR): EBV | Piperacillin/tazobactam | Confirmation of empiric therapy |

| N12 | 78/m | Pulmonary | E. faecium, HSV-1, EBV | Negative | Serum (PCR): HSV-1 | Meropenem | Initiation of vancomycin and aciclovir treatment |

| N19 | 31/m | Unknown | S. aureus, S. marcescens, E. faecium | S. epidermidis | BAL: S. aureus | Meropenem | Initiation of vancomycin treatment, confirmation of empiric therapy |

| N25 | 80/f | Pulmonary or wound | K. pneumoniae | Negative | BAL: K. pneumoniae | Meropenem | Confirmation of empiric therapy |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leitl, C.J.; Stoll, S.E.; Wetsch, W.A.; Kammerer, T.; Mathes, A.; Böttiger, B.W.; Seifert, H.; Dusse, F. Next-Generation Sequencing in Critically Ill COVID-19 Patients with Suspected Bloodstream Infections: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1466. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12041466

Leitl CJ, Stoll SE, Wetsch WA, Kammerer T, Mathes A, Böttiger BW, Seifert H, Dusse F. Next-Generation Sequencing in Critically Ill COVID-19 Patients with Suspected Bloodstream Infections: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(4):1466. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12041466

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeitl, Christoph J., Sandra E. Stoll, Wolfgang A. Wetsch, Tobias Kammerer, Alexander Mathes, Bernd W. Böttiger, Harald Seifert, and Fabian Dusse. 2023. "Next-Generation Sequencing in Critically Ill COVID-19 Patients with Suspected Bloodstream Infections: A Retrospective Cohort Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 4: 1466. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12041466

APA StyleLeitl, C. J., Stoll, S. E., Wetsch, W. A., Kammerer, T., Mathes, A., Böttiger, B. W., Seifert, H., & Dusse, F. (2023). Next-Generation Sequencing in Critically Ill COVID-19 Patients with Suspected Bloodstream Infections: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(4), 1466. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12041466