Nutritional Care Practices in Geriatric Rehabilitation Facilities across Europe: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Respondents

2.3. Survey

2.4. Recruitment and Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

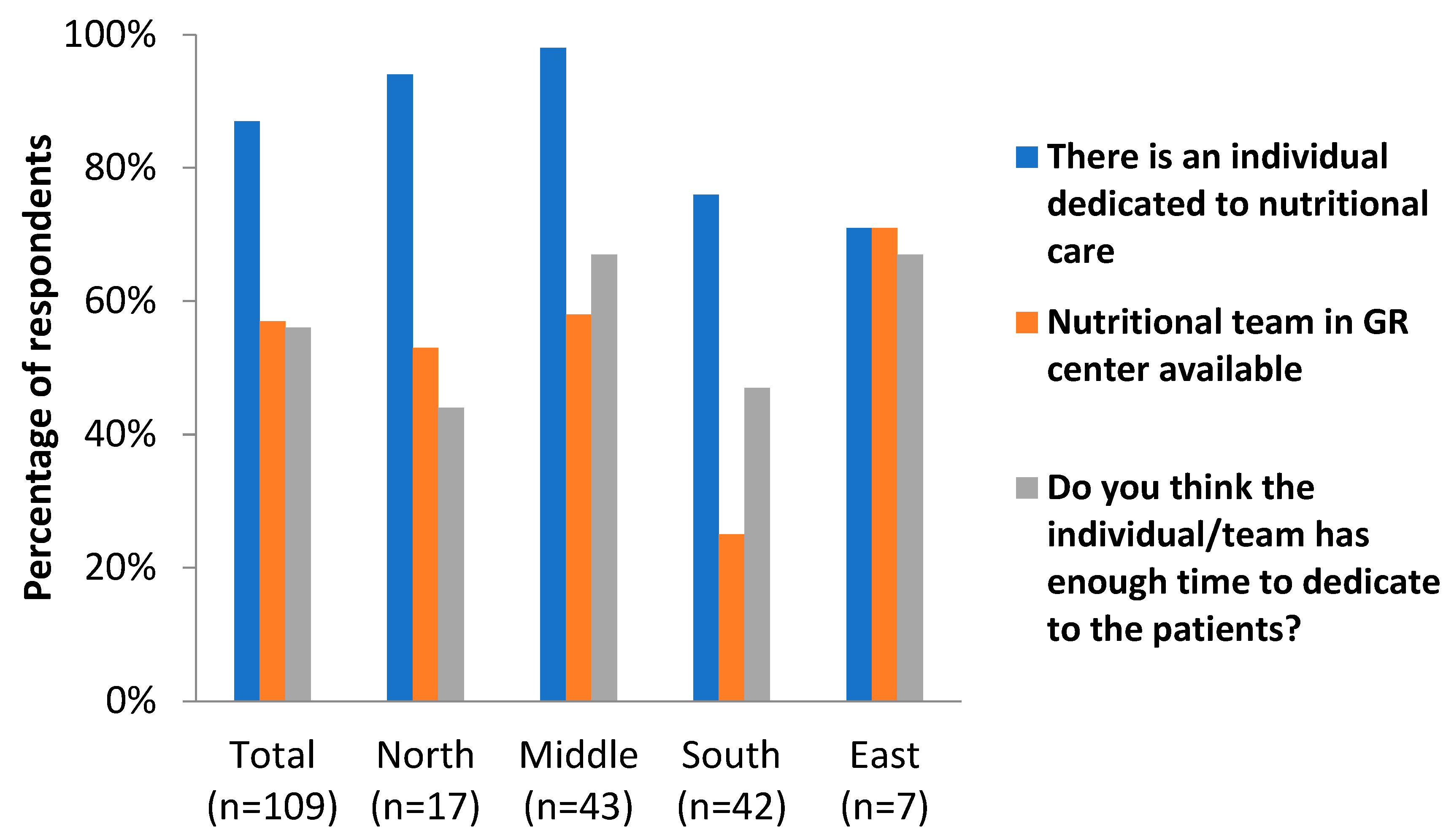

3.1. Dedicated Nutritional Care

3.2. Reasons for the Lack of Time Dedicated to Nutritional Care

3.3. Screening for (Risk of) Malnutrition

3.4. Treating People with (Risk of) Malnutrition

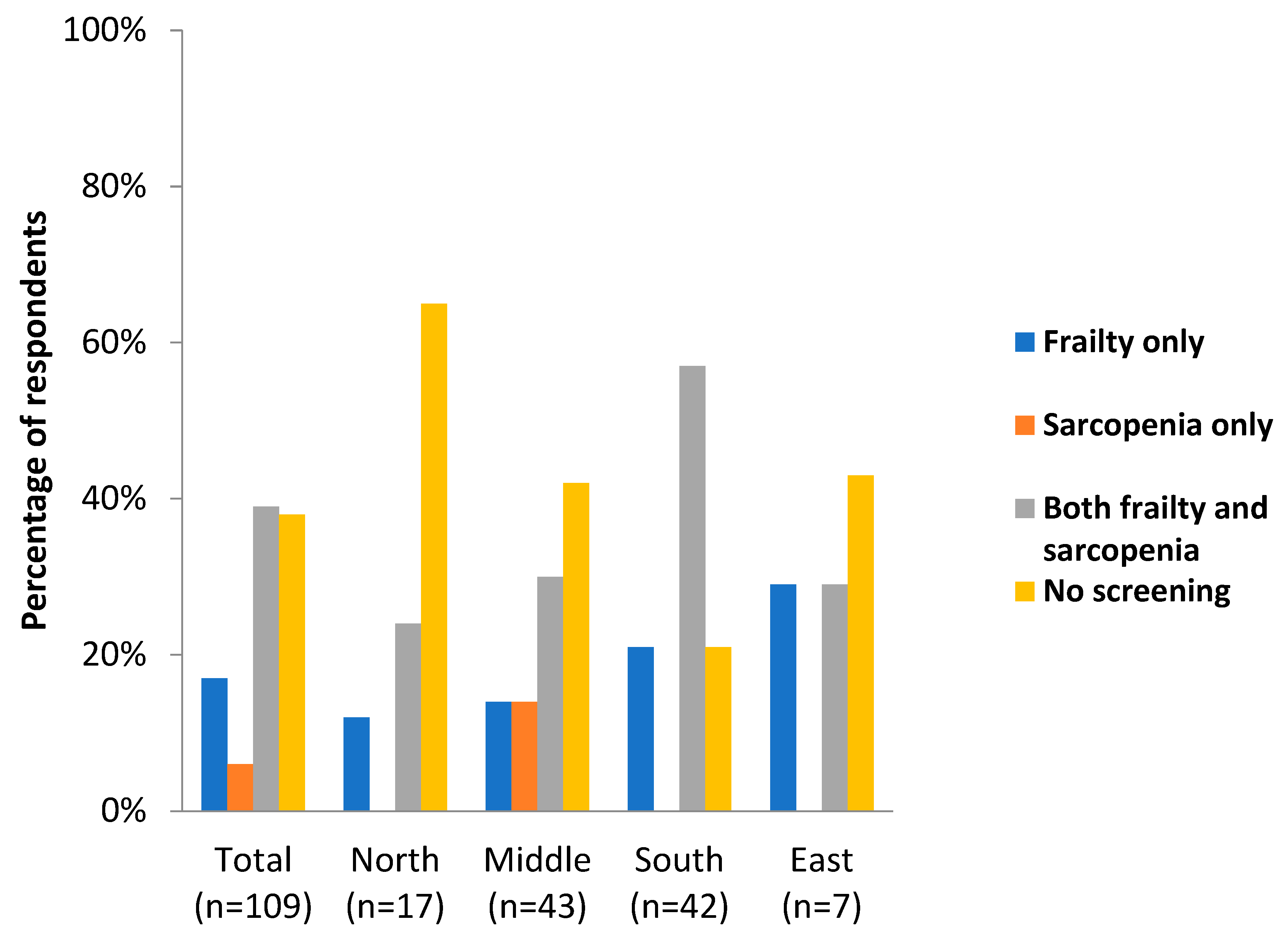

3.5. Screening for and Treating Frailty and Sarcopenia

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Implications for Practice and Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grund, S.; Gordon, A.L.; van Balen, R.; Bachmann, S.; Cherubini, A.; Landi, F.; Stuck, A.E.; Becker, C.; Achterberg, W.P.; Bauer, J.M.; et al. European consensus on core principles and future priorities for geriatric rehabilitation: Consensus statement. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2020, 11, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wojzischke, J.; van Wijngaarden, J.; van den Berg, C.; Cetinyurek-Yavuz, A.; Diekmann, R.; Luiking, Y.; Bauer, J. Nutritional status and functionality in geriatric rehabilitation patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2020, 11, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Low, S.; Wee, E.; Dorevitch, M. Impact of place of residence, frailty and other factors on rehabilitation outcomes post hip fracture. Age Ageing 2021, 50, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landi, F.; Calvani, R.; Ortolani, E.; Salini, S.; Martone, A.M.; Santoro, L.; Santoliquido, A.; Sisto, A.; Picca, A.; Marzetti, E. The association between sarcopenia and functional outcomes among older patients with hip fracture undergoing in-hospital rehabilitation. Osteoporos. Int. 2017, 28, 1569–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Reijnierse, E.M.; Pacifico, J.; Wan, C.S.; Maier, A.B. Sarcopenia is associated with 3-month and 1-year mortality in geriatric rehabilitation inpatients: RESORT. Age Ageing 2021, 50, 2147–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendelson, G.; Katz, Y.; Shahar, D.R.; Bar, O.; Lehman, Y.; Spiegel, D.; Ochayon, Y.; Shavit, N.; Mimran Nahon, D.; Radinski, Y.; et al. Nutritional Status and Osteoporotic Fracture Rehabilitation Outcomes in Older Adults. J. Nutr. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2018, 37, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cederholm, T.; Barazzoni, R.; Austin, P.; Ballmer, P.; Biolo, G.; Bischoff, S.C.; Compher, C.; Correia, I.; Higashiguchi, T.; Holst, M.; et al. ESPEN guidelines on definitions and terminology of clinical nutrition. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 36, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, A.L.; Nielsen, R.L.; Houlind, M.B.; Tavenier, J.; Rasmussen, L.J.H.; Jørgensen, L.M.; Treldal, C.; Beck, A.M.; Pedersen, M.M.; Andersen, O.; et al. Risk of Malnutrition upon Admission and after Discharge in Acutely Admitted Older Medical Patients: A Prospective Observational Study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cereda, E.; Pedrolli, C.; Klersy, C.; Bonardi, C.; Quarleri, L.; Cappello, S.; Turri, A.; Rondanelli, M.; Caccialanza, R. Nutritional status in older persons according to healthcare setting: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence data using MNA(®). Clin. Nutr. 2016, 35, 1282–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zwienen-Pot, J.I.; Visser, M.; Kuijpers, M.; Grimmerink, M.F.A.; Kruizenga, H.M. Undernutrition in nursing home rehabilitation patients. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 36, 755–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, L.P.; Tangen, C.M.; Walston, J.; Newman, A.B.; Hirsch, C.; Gottdiener, J.; Seeman, T.; Tracy, R.; Kop, W.J.; Burke, G.; et al. Frailty in older adults: Evidence for a phenotype. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2001, 56, M146–M156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theou, O.; Jones, G.R.; Overend, T.J.; Kloseck, M.; Vandervoort, A.A. An exploration of the association between frailty and muscle fatigue. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2008, 33, 651–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Bahat, G.; Bauer, J.; Boirie, Y.; Bruyère, O.; Cederholm, T.; Cooper, C.; Landi, F.; Rolland, Y.; Sayer, A.A.; et al. Sarcopenia: Revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing 2019, 48, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaap, L.A.; van Schoor, N.M.; Lips, P.; Visser, M. Associations of Sarcopenia Definitions, and Their Components, With the Incidence of Recurrent Falling and Fractures: The Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2018, 73, 1199–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, K.; May, C.; Patel, H.P.; Baxter, M.; Sayer, A.A.; Roberts, H. A feasibility study of implementing grip strength measurement into routine hospital practice (GRImP): Study protocol. Pilot. Feasibility Stud. 2016, 2, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, D.P.; Teo, K.K.; Rangarajan, S.; Lopez-Jaramillo, P.; Avezum, A., Jr.; Orlandini, A.; Seron, P.; Ahmed, S.H.; Rosengren, A.; Kelishadi, R.; et al. Prognostic value of grip strength: Findings from the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study. Lancet 2015, 386, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alley, D.E.; Shardell, M.D.; Peters, K.W.; McLean, R.R.; Dam, T.T.; Kenny, A.M.; Fragala, M.S.; Harris, T.B.; Kiel, D.P.; Guralnik, J.M.; et al. Grip strength cutpoints for the identification of clinically relevant weakness. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2014, 69, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, L.; Abete, P.; Bellelli, G.; Bo, M.; Cherubini, A.; Corica, F.; Di Bari, M.; Maggio, M.; Manca, G.M.; Rizzo, M.R.; et al. Prevalence and Clinical Correlates of Sarcopenia, Identified According to the EWGSOP Definition and Diagnostic Algorithm, in Hospitalized Older People: The GLISTEN Study. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2017, 72, 1575–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martone, A.M.; Bianchi, L.; Abete, P.; Bellelli, G.; Bo, M.; Cherubini, A.; Corica, F.; Di Bari, M.; Maggio, M.; Manca, G.M.; et al. The incidence of sarcopenia among hospitalized older patients: Results from the Glisten study. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2017, 8, 907–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steihaug, O.M.; Gjesdal, C.G.; Bogen, B.; Kristoffersen, M.H.; Lien, G.; Ranhoff, A.H. Sarcopenia in patients with hip fracture: A multicenter cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0184780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligthart-Melis, G.C.; Luiking, Y.C.; Kakourou, A.; Cederholm, T.; Maier, A.B.; de van der Schueren, M.A.E. Frailty, Sarcopenia, and Malnutrition Frequently (Co-)occur in Hospitalized Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 1216–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Churilov, I.; Churilov, L.; MacIsaac, R.J.; Ekinci, E.I. Systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence of sarcopenia in post acute inpatient rehabilitation. Osteoporos. Int. 2018, 29, 805–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, D.; Jackson, T.; Sapey, E.; Lord, J.M. Frailty and sarcopenia: The potential role of an aged immune system. Ageing Res. Rev. 2017, 36, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, D.E.; Welch, S.A.; Montgomery, C.D.; Hatcher, J.B.; Duggan, M.C.; Greysen, S.R. Low hospital mobility-resurgence of an old epidemic within a new pandemic and future solutions. Age Ageing 2021, 50, 1439–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudart, C.; Sanchez-Rodriguez, D.; Locquet, M.; Reginster, J.Y.; Lengelé, L.; Bruyère, O. Malnutrition as a Strong Predictor of the Onset of Sarcopenia. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reijnierse, E.M.; de van der Schueren, M.A.E.; Trappenburg, M.C.; Doves, M.; Meskers, C.G.M.; Maier, A.B. Lack of knowledge and availability of diagnostic equipment could hinder the diagnosis of sarcopenia and its management. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0185837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grund, S.; van Wijngaarden, J.P.; Gordon, A.L.; Schols, J.; Bauer, J.M. EuGMS survey on structures of geriatric rehabilitation across Europe. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2020, 11, 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkert, D.; Beck, A.M.; Cederholm, T.; Cruz-Jentoft, A.; Hooper, L.; Kiesswetter, E.; Maggio, M.; Raynaud-Simon, A.; Sieber, C.; Sobotka, L.; et al. ESPEN practical guideline: Clinical nutrition and hydration in geriatrics. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 41, 958–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, J.; Ke, Y.Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.Y.; Ren, C.X.; Xu, J.; Zhu, Y.X.; Zhang, X.L.; Zhang, X.Y. Comparison of the value of malnutrition and sarcopenia for predicting mortality in hospitalized old adults over 80 years. Exp. Gerontol. 2020, 138, 111007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petermann-Rocha, F.; Pell, J.P.; Celis-Morales, C.; Ho, F.K. Frailty, sarcopenia, cachexia and malnutrition as comorbid conditions and their associations with mortality: A prospective study from UK Biobank. J. Public Health 2022, 44, e172–e180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishioka, S.; Matsushita, T.; Yamanouchi, A.; Okazaki, Y.; Oishi, K.; Nishioka, E.; Mori, N.; Tokunaga, Y.; Onizuka, S. Prevalence and Associated Factors of Coexistence of Malnutrition and Sarcopenia in Geriatric Rehabilitation. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, V.M.H.; Pang, B.W.J.; Lau, L.K.; Jabbar, K.A.; Seah, W.T.; Chen, K.K.; Ng, T.P.; Wee, S.L. Malnutrition and Sarcopenia in Community-Dwelling Adults in Singapore: Yishun Health Study. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2021, 25, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almohaisen, N.; Gittins, M.; Todd, C.; Sremanakova, J.; Sowerbutts, A.M.; Aldossari, A.; Almutairi, A.; Jones, D.; Burden, S. Prevalence of Undernutrition, Frailty and Sarcopenia in Community-Dwelling People Aged 50 Years and Above: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cesari, M.; Landi, F.; Vellas, B.; Bernabei, R.; Marzetti, E. Sarcopenia and physical frailty: Two sides of the same coin. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2014, 6, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, R.; Sayer, A.A. Sarcopenia and frailty: New challenges for clinical practice. Clin. Med. 2016, 16, 455–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderström, L.; Rosenblad, A.; Thors Adolfsson, E.; Bergkvist, L. Malnutrition is associated with increased mortality in older adults regardless of the cause of death. Br. J. Nutr. 2017, 117, 532–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruyère, O.; Buckinx, F.; Beaudart, C.; Reginster, J.Y.; Bauer, J.; Cederholm, T.; Cherubini, A.; Cooper, C.; Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Landi, F.; et al. How clinical practitioners assess frailty in their daily practice: An international survey. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2017, 29, 905–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin-Cantero, A.; Reijnierse, E.M.; Gill, B.M.T.; Maier, A.B. Factors influencing the efficacy of nutritional interventions on muscle mass in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr. Rev. 2021, 79, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, G.H.; Tsai, M.C.; Tsai, H.W.; Chang, C.C.; Hou, W.H. Effects of branched-chain amino acid-rich supplementation on EWGSOP2 criteria for sarcopenia in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Nutr. 2022, 61, 637–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, J. Nutritional interventions in sarcopenia: Where do we stand? Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2018, 21, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, C.H.; Roche, H.M. Nutrition and physical activity countermeasures for sarcopenia: Time to get personal? Nutr. Bull. 2018, 43, 374–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo, M.; Merchant, R.A.; Morley, J.E.; Anker, S.D.; Aprahamian, I.; Arai, H.; Aubertin-Leheudre, M.; Bernabei, R.; Cadore, E.L.; Cesari, M.; et al. International Exercise Recommendations in Older Adults (ICFSR): Expert Consensus Guidelines. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2021, 25, 824–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Wijngaarden, J.P.; Wojzischke, J.; van den Berg, C.; Cetinyurek-Yavuz, A.; Diekmann, R.; Luiking, Y.C.; Bauer, J.M. Effects of Nutritional Interventions on Nutritional and Functional Outcomes in Geriatric Rehabilitation Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 1207–1215.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, P.Y.; Huang, K.S.; Chen, K.M.; Chou, C.P.; Tu, Y.K. Exercise, Nutrition, and Combined Exercise and Nutrition in Older Adults with Sarcopenia: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. Maturitas 2021, 145, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, S.; Kushibe, T.; Akezaki, Y.; Horiike, N. Effects of Exercise Therapy and Nutrition Therapy on Patients with Possible Malnutrition and Sarcopenia in a Recovery Rehabilitation Ward. Acta Med. Okayama 2022, 76, 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eglseer, D.; Visser, M.; Volkert, D.; Lohrmann, C. Nutrition education on malnutrition in older adults in European medical schools: Need for improvement? Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2019, 10, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eglseer, D.; Halfens, R.J.G.; Schüssler, S.; Visser, M.; Volkert, D.; Lohrmann, C. Is the topic of malnutrition in older adults addressed in the European nursing curricula? A MaNuEL study. Nurse Educ. Today 2018, 68, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lueg, G.; Wirth, R.; Kwiatkowski, J.; Rösler, A.; Jäger, M.; Gehrke, I.; Volkert, D.; Pourhassan, M. Low Self-Perception of Malnutrition in Older Hospitalized Patients. Clin. Interv. Aging 2020, 15, 2219–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Profession | Total (n = 109) | North (n = 17) | Central (n = 43) | South (n = 42) | East (n = 7) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geriatrician | 50% | 24% | 44% | 64% | 57% |

| Dietician | 37% | 65% | 44% | 21% | 14% |

| Physiotherapist | 1% | 0% | 0% | 2% | 0% |

| Other | 13% | 12% | 12% | 12% | 29% |

| Work experience in profession (years) | |||||

| 0–5 | 19% | 35% | 9% | 20% | 43% |

| 6–10 | 18% | 18% | 16% | 17% | 29% |

| 11–15 | 18% | 12% | 16% | 22% | 14% |

| 16–20 | 12% | 0% | 14% | 15% | 14% |

| >20 | 33% | 35% | 44% | 27% | 0% |

| Followed education on nutrition | |||||

| 39% | 41% | 30% | 45% | 43% | |

| Total (n = 109) | North (n = 17) | Central (n = 43) | South (n = 42) | East (n = 7) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Is there an individual dedicated to nutritional care? | |||||

| Yes | 87% | 94% | 98% | 76% | 71% |

| Profession of individual dedicated to nutritional care | |||||

| Dietician | 67% | 94% | 88% | 41% | 29% |

| Nutritionist | 19% | 18% | 5% | 33% | 29% |

| Geriatrician | 6% | 0% | 5% | 12% | 0% |

| Dietetic assistant | 6% | 0% | 12% | 2% | 0% |

| Other | 11% | 12% | 7% | 12% | 29% |

| Nutritional team in GR center | |||||

| Yes | 57% | 53% | 58% | 25% | 71% |

| Members of the nutritional team | |||||

| Dietician | 56% | 53% | 58% | 55% | 57% |

| Speech therapist | 37% | 41% | 44% | 21% | 71% |

| Occupational therapist | 23% | 24% | 26% | 17% | 43% |

| Dentist | 6% | 12% | 9% | 0% | 0% |

| Other (physician, nurses, pharmacist) | 24% | 23% | 5% | 29% | 17% |

| Do you think the individual/team has enough time to dedicate to the patients? | |||||

| Yes | 56% | 44% | 67% | 47% | 67% |

| Total (n = 109) | North (n = 17) | Central (n = 43) | South (n = 42) | East (n = 7) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do you screen for (risk of) malnutrition? | |||||

| Yes, all patients | 73% | 77% | 77% | 76% | 29% |

| Yes, but only selected patients | 24% | 12% | 21% | 24% | 71% |

| No | 3% | 12% | 2% | 0% | 0% |

| Do you use (inter)national nutritional screening guidelines? | |||||

| Yes | 79% | 94% | 74% | 76% | 86% |

| How do you screen for (risk of) malnutrition? | |||||

| Standard screening tool (e.g., MUST, MNA, SNAQ) | 95% | 100% | 91% | 98% | 100% |

| BMI | 60% | 65% | 61% | 57% | 57% |

| Weight | 61% | 59% | 63% | 62% | 43% |

| Clinical presentation | 60% | 47% | 58% | 67% | 57% |

| Other (mostly albumin, biomarkers) | 17% | 6% | 19% | 17% | 28% |

| Do you perform a more detailed nutritional assessment? | |||||

| Yes | 42% | 59% | 19% | 55% | 71% |

| Total (n = 109) | North (n = 17) | Central (n = 43) | South (n = 42) | East (n = 7) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment plan for people at risk of malnutrition based on nutritional care guidelines? | |||||

| Yes | 68% | 52% | 72% | 69% | 71% |

| No | 19% | 29% | 12% | 21% | 29% |

| Not applicable | 13% | 18% | 16% | 10% | 0% |

| What does the treatment plan for patients at risk for malnutrition consist of? | |||||

| Dietary counseling | 85% | 94% | 93% | 74% | 86% |

| Prescription of ONS | 76% | 94% | 65% | 76% | 100% |

| Dietary adaptations | 75% | 94% | 70% | 74% | 71% |

| Other | 7% | 6% | 7% | 7% | 14% |

| No treatment | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| What does the treatment plan for patients with malnutrition consist of? | |||||

| Dietary counseling | 90% | 94% | 95% | 83% | 86% |

| Prescription of ONS | 85% | 100% | 84% | 86% | 57% |

| Dietary adaptations | 78% | 88% | 72% | 79% | 86% |

| No treatment | 1% | 0% | 2% | 0% | 0% |

| SARCOPENIA | Total (n = 106) | North (n = 16) | Central (n = 42) | South (n = 40) | East (n = 7) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| How do you treat sarcopenia? | |||||

| Physical exercise (aerobic/resistance/balance) | 85% | 63% | 91% | 85% | 100% |

| Food fortification/high-energy and/or high-protein diet/additional food | 81% | 63% | 86% | 80% | 100% |

| Texture-modified food | 39% | 19% | 36% | 48% | 57% |

| ONSs | 73% | 63% | 71% | 80% | 71% |

| Other diet modifications | 35% | 25% | 41% | 33% | 43% |

| Sarcopenia is not being treated | 8% | 25% | 2% | 5% | 14% |

| If a patient is diagnosed with sarcopenia, do you also screen for and/or treat malnutrition? | |||||

| Yes | 92% | 86% | 93% | 95% | 86% |

| FRAILTY | Total (n = 103) | North (n = 16) | Middle (n = 39) | South (n = 41) | East (n = 7) |

| How do you treat frailty? | |||||

| Physical exercise (aerobic/resistance/balance) | 87% | 69% | 87% | 93% | 100% |

| Food fortification/high-energy and/or high-protein diet/additional food | 79% | 69% | 74% | 85% | 86% |

| Texture-modified food | 48% | 50% | 33% | 56% | 71% |

| ONSs | 66% | 69% | 64% | 68% | 57% |

| Other diet modifications | 41% | 38% | 41% | 39% | 57% |

| Frailty is not being treated | 11% | 19% | 13% | 7% | 0.0% |

| If a patient is diagnosed with frailty, do you also screen for and/or treat malnutrition? | |||||

| Yes | 90% | 80% | 93% | 93% | 86% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Everink, I.H.J.; Grund, S.; Benzinger, P.; de Vries, A.; Gordon, A.L.; van Wijngaarden, J.P.; Bauer, J.M.; Schols, J.M.G.A. Nutritional Care Practices in Geriatric Rehabilitation Facilities across Europe: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2918. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12082918

Everink IHJ, Grund S, Benzinger P, de Vries A, Gordon AL, van Wijngaarden JP, Bauer JM, Schols JMGA. Nutritional Care Practices in Geriatric Rehabilitation Facilities across Europe: A Cross-Sectional Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(8):2918. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12082918

Chicago/Turabian StyleEverink, Irma H. J., Stefan Grund, Petra Benzinger, Anne de Vries, Adam L. Gordon, Janneke P. van Wijngaarden, Jürgen M. Bauer, and Jos M. G. A. Schols. 2023. "Nutritional Care Practices in Geriatric Rehabilitation Facilities across Europe: A Cross-Sectional Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 8: 2918. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12082918