Inconsistencies in Pregnant Mothers’ Attitudes and Willingness to Donate Umbilical Cord Stem Cells: A Cross-Sectional Analysis from Saudi Arabia

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Age, education, nationality, and religious orientation significantly predict women’s intention to donate.

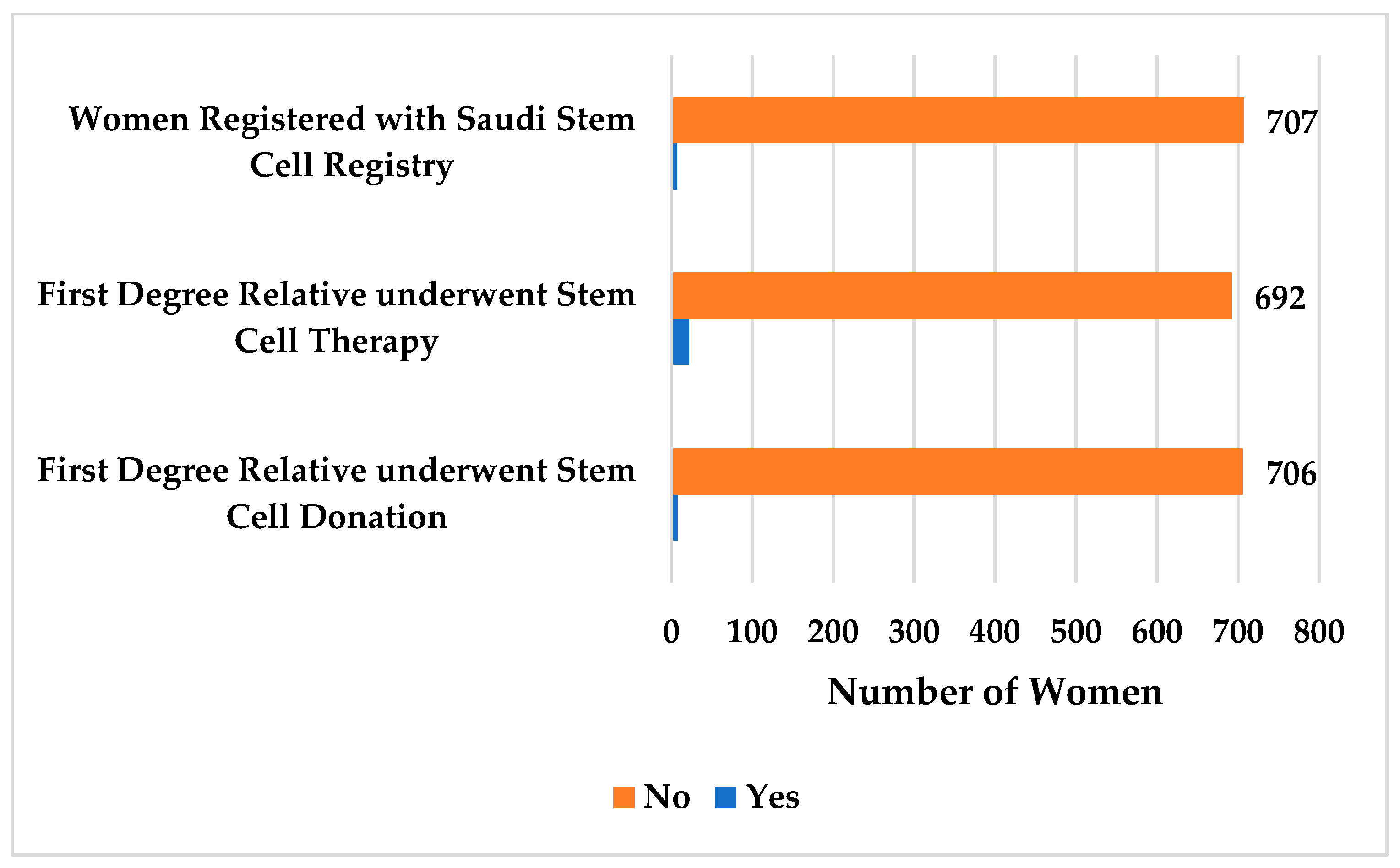

- Having a first-degree relative who has undergone stem cell donation will be positively associated with women’s willingness to donate cord stem cells as compared to those who do not have such exposure.

- Having a first-degree relative who has undergone stem cell therapy will be positively associated with women’s willingness to donate cord stem cells as compared to those who do not have such exposure.

- Higher levels of awareness and acceptance attitudes will significantly predict current registration with the Saudi Stem Cell Registry and willingness to donate.

- Rejection attitudes will be negatively related to the intention to donate.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Sample Size Estimation

2.2. Survey Tool

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Ethical Approval and Considerations

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hoang, D.M.; Pham, P.T.; Bach, T.Q.; Ngo, A.T.L.; Nguyen, Q.T.; Phan, T.T.K.; Nguyen, G.H.; Le, P.T.T.; Hoang, V.T.; Forsyth, N.R.; et al. Stem cell-based therapy for human diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donnelly, H.; Salmeron-Sanchez, M.; Dalby, M.J. Designing stem cell niches for differentiation and self-renewal. J. R. Soc. Interface 2018, 15, 20180388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mousaei Ghasroldasht, M.; Seok, J.; Park, H.-S.; Liakath Ali, F.B.; Al-Hendy, A. Stem cell therapy: From idea to clinical practice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, D.T.; Rogers, I. Umbilical cord blood: A unique source of pluripotent stem cells for regenerative medicine. Curr. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2007, 2, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monti, M.; Imberti, B.; Bianchi, N.; Pezzotta, A.; Morigi, M.; Del Fante, C.; Redi, C.A.; Perotti, C. A novel method for isolation of pluripotent stem cells from human umbilical cord blood. Stem Cells Dev. 2017, 26, 1258–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aly, R.M. Current state of stem cell-based therapies: An overview. Stem Cell Investig. 2020, 7, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.A.; Gray, D.; Lomova, A.; Kohn, D.B. Hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy: Progress and lessons learned. Cell Stem Cell 2017, 21, 574–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayani, H.; Wagner, J.E.; Broxmeyer, H.E. Cord blood research, banking, and transplantation: Achievements, challenges, and perspectives. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2020, 55, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Querol, S.; Rocha, V. Procurement and management of cord blood. In The EBMT Handbook: Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation and Cellular Therapies; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, L.A.; Bernardino, E.; Crozeta, K.; Guimarães, P.R.B. Good practices in collecting umbilical cord and placental blood. Rev. Lat. Am. Enferm. 2016, 24, e2770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onkar, P.A.S. Cord Blood Banking Services Market: Global Opportunity Analysis and Industry Forecast, 2020–2030; Global Company: Jerusalem, Israel, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, A.O.; Wagner, J.E. Umbilical cord blood transplants: Current status and evolving therapies. Front. Pediatr. 2020, 8, 570282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, G.N.; Kerridge, I.H.; O’Brien, T.A. Umbilical cord blood banking: Public good or private benefit? Med. J. Aust. 2008, 188, 533–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armson, B.A.; Allan, D.S.; Casper, R.F. Umbilical cord blood: Counselling, collection, and banking. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2015, 37, 832–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerdfaramarzi, M.S.; Bazmi, S.; Kiani, M.; Afshar, L.; Fadavi, M.; Enjoo, S.A. Ethical challenges of cord blood banks: A scoping review. J. Med. Life 2022, 15, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waller-Wise, R. Umbilical cord blood: Information for childbirth educators. J. Perinat. Educ. 2011, 20, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leanza, V.; Genovese, F.; Marilli, I.; Carbonaro, A.; Vizzini, S.; Leanza, G.; Pafumi, C. Umbilical cord blood collection: Ethical aspects. Gynecol Obs. 2012, 2, 932–2161. [Google Scholar]

- Gebbie, K.; Hanna, K.; Meyer, E.A. Cord Blood: Establishing a National Hematopoietic Stem Cell Bank Program; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; ISBN 0309095867. [Google Scholar]

- Kindwall-Keller, T.L.; Ballen, K.K. Umbilical cord blood: The promise and the uncertainty. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2020, 9, 1153–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grano, C.; Scafa, V.; Zucaro, E.; Abad, R.; Lombardo, C.; Violani, C. Knowledge and sources of information on umbilical cord blood donation in pregnant women. Cell Tissue Bank. 2020, 21, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.; Alhajali, S.; Aswad, S. Knowledge, Attitude, and Effect on Future Practice Among Pregnant Women About Cord Blood Banking: A UAE Population-Based Survey. J. Health Med. Nurs. 2018, 51, 67–73. [Google Scholar]

- Aboushady, R.M.; Elhusein, A.M.; Ahmed, A.R.; Goda, A.A. Assessment of Pregnant Women knowledge and attitude towards Umbilical Cord Banking and Stem Cell. Egypt. J. Health Care 2021, 12, 1152–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawdat, D.; AlTwijri, S.; AlSemari, H.; Saade, M.; Alaskar, A. Public awareness on cord blood banking in Saudi Arabia. Stem Cells Int. 2018, 2018, 8037965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrehaili, A.A.; Alshihri, S.; Althobaiti, R.; Alazizi, N.; Gharib, A.F.; Bakhuraysah, M.M.; Alzahrani, H.A.; Alhuthali, H.M. The Concept of Stem Cells Transplantation: Identifying the Acceptance and Refusal Rates among Saudi Population. Int. J. Med. Res. Health Sci. 2022, 3, 8–16. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, D.; Kaur, S.; Kamath, A. Banking umbilical cord blood (UCB) stem cells: Awareness, attitude and expectations of potential donors from one of the largest potential repository (India). PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0155782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleh, F.A. Knowledge and attitude among lebanese pregnant women toward cord blood stem cell storage and donation. Medicina 2019, 55, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashed, A.B.A.A.; Shehata, H.S.I. Evaluation of Pregnant Women’s Knowledge and Attitude toward Banking of Stem Cells from the Umbilical Cord Blood before and after Counseling. Evaluation 2018, 53, 78–88. [Google Scholar]

- Velikonja, N.K.; Erjavec, K.; Knežević, M. Knowledge, Awareness, and Attitudes toward Umbilical Cord Blood Biobanking. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2021, 9, 702–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, M.; Alessandri, G.; Abbad, R.; Grano, C. Determinants of the intention to donate umbilical cord blood in pregnant women. Vox Sang. 2022, 117, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlMojel, S.A.; Ibrahim, S.F.; Alshammari, L.K.; Zadah, M.H.; Thaqfan, D.A.A. Saudi population Awareness and Attitude Regarding Stem Cell Donation. Arch. Pharm. Pract. 2021, 12, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aftab, T.; Khyzer, E. Knowledge and Attitude about Stem Cells and their Potential Applications in Field of Medicine among Medical Students of Arar, Saudi Arabia. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2021, 15, CC06–CC09. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tork, H.; Alraffaa, S.; Almutairi, K.; Alshammari, N.; Alharbi, A.; Alonzi, A. Stem cells: Knowledge and attitude among health care providers in Qassim region, KSA. Int. J. Adv. Nurs. Stud. 2017, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhadlaq, A.; Al-Maflehi, N.; Alzahrani, S.; AlAssiri, A. Assessment of knowledge and attitude toward stem cells and their implications in dentistry among recent graduates of dental schools in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Dent. J. 2019, 31, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, F. Knowledge of and attitudes towards stem cells and their applications: A questionnaire-based cross-sectional study from King Abdulaziz university. Arab. J. Geosci. 2020, 3, 18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Hurissi, E.; Hakami, A.; Homadi, J.; Kariri, F.; Abu-Jabir, E.; Alamer, R.; Mobarki, R.; Jaly, A.A.; Alhazmi, A.H. Awareness and Acceptance of Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation for Sickle Cell Disease in Jazan Province, Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2022, 14, e21013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdullah, B.; Reem, A.K.; Essra, A.K.; Mohamed, A.; Mohammed, A.; Ibrahim, A.T.; Motasim, A.B.; Bawazir, A.A. Knowledge, Attitude and Motivation toward Stem Cell Transplantation and Donation among Saudi Population in Riyadh. Int. J. Med. Res. Health Sci. 2021, 10, 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Debiazi Zomer, H.; Girardi Gonçalves, A.J.; Andrade, J.; Benedetti, A.; Gonçalves Trentin, A. Lack of information about umbilical cord blood banking leads to decreased donation rates among Brazilian pregnant women. Cell Tissue Bank. 2021, 22, 597–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvaterra, E.; Casati, S.; Bottardi, S.; Brizzolara, A.; Calistri, D.; Cofano, R.; Folliero, E.; Lalatta, F.; Maffioletti, C.; Negri, M. An analysis of decision making in cord blood donation through a participatory approach. Transfus. Apher. Sci. 2010, 42, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allum, N.; Allansdottir, A.; Gaskell, G.; Hampel, J.; Jackson, J.; Moldovan, A.; Priest, S.; Stares, S.; Stoneman, P. Religion and the public ethics of stem-cell research: Attitudes in Europe, Canada and the United States. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0176274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordens, C.; O’Connor, M.; Kerridge, I.; Steward, C.; Cameron, A.; Keown, D.; Lawrence, J.; McGarrity, A.; Sachedina, A.; Tobin, B. Religious perspectives on umbilical cord blood banking. J. Law Med. 2012, 19, 497–511. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.; Han, S.; Shin, M. Influencing factors on the cord-blood donation of post-partum women. Nurs. Health Sci. 2015, 17, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Categories | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (M = 29.5; S.D. = 5.2; Range = 19–44) | 19–30 years | 413 | 57% |

| 31–44 years | 301 | 43% | |

| Education | School | 68 | 10% |

| College | 126 | 17% | |

| University | 520 | 73% | |

| Nationality | Saudi | 637 | 89% |

| Non-Saudi | 77 | 11% | |

| Religious Orientation | Islam | 684 | 96% |

| Hindu | 16 | 2.0% | |

| Christian | 14 | 2.0% | |

| Place of Residence | Medina | 51 | 7.0% |

| Mecca | 77 | 11% | |

| Riyadh | 70 | 10% | |

| Ha’il | 68 | 8.0% | |

| Al-Jaouf | 50 | 7.0% | |

| Shirqia | 71 | 10% | |

| Al-Qaseem | 50 | 7.0% | |

| Tabuk | 57 | 8.0% | |

| Aseer | 49 | 7.0% | |

| Najran | 44 | 6.0% | |

| Al-Hadud Shamaliya | 50 | 7.0% | |

| Jazzan | 47 | 7.0% | |

| Al-Baha | 30 | 5.0% |

| Do You Know What Stem Cells Are? | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | 672 | 94% |

| No | 42 | 6.0% |

| Do you know what umbilical cord cells are? | Frequency | Percentage |

| Yes | 657 | 92% |

| No | 57 | 8.0% |

| Not aware of stem cells/umbilical cord cells | 47 | 7.0% |

| Sources of knowledge about stem cells | Frequency | Percentage |

| Formal education | 127 | 18% |

| Social Media | 418 | 58% |

| Online Sources | 77 | 11% |

| Friends | 26 | 4.0% |

| TV Programs | 19 | 3.0% |

| Awareness of Umbilical Cord Stem Cell Donation and Therapy | Mean (S.D.) |

|---|---|

| Aware of diseases that are currently being treated in reliable ways. | 3.43 (0.67) |

| Aware of the potential benefits. | 3.40 (0.65) |

| Aware of the potential risks. | 2.80 (0.94) |

| Aware that the Saudi Stem Cell Donor Registry is the only authorized body in Saudi Arabia to collect stem cells from donors. | 2.89 (0.82) |

| Aware of other organizations that collect stem cells from donors in Saudi Arabia. | 1.37 (0.94) |

| Total Awareness Mean Score | 13.88 (2.73) |

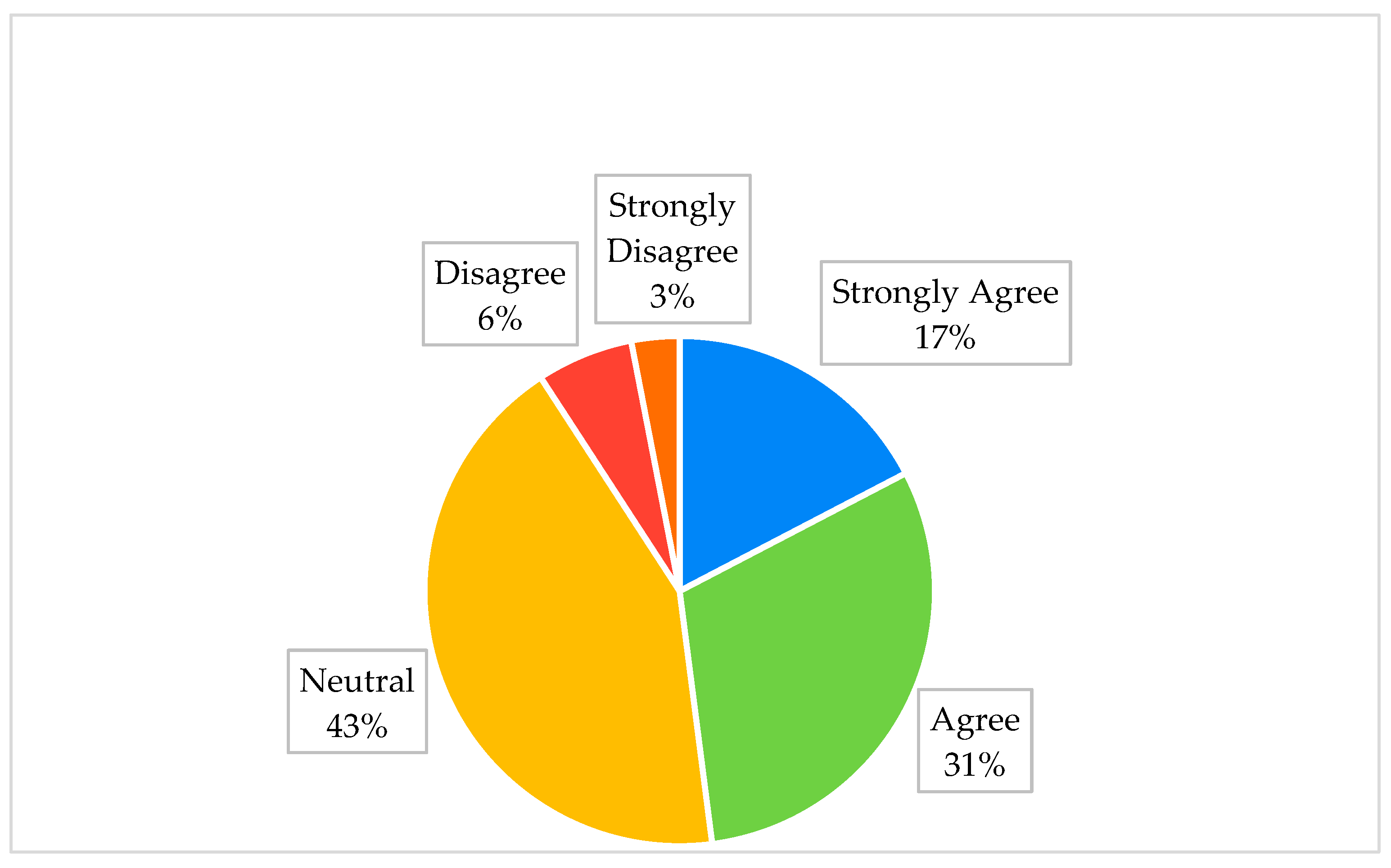

| Acceptance Attitudes | Mean (S.D.) |

| It is okay to donate umbilical cord stem cells. | 3.47 (0.65) |

| Women about to deliver should volunteer to donate umbilical cord stem cells for treatment. | 3.49 (0.62) |

| Women who are about to deliver should volunteer to donate umbilical cord stem cells for research. | 3.23 (0.67) |

| Stem cell transplantation should be practiced on a large scale. | 3.69 (0.58) |

| Support allowing pregnant mothers to store cord blood stem cells for future purposes. | 3.62 (0.65) |

| Total Acceptance Attitude Mean Score | 17.51 (2.74) |

| Rejection Attitudes | Mean (S.D.) |

| Umbilical cord stem cell transplantation may open the door to the destruction of innocent human life. | 0.22 (0.61) |

| Umbilical cord stem cell transplantation values individual lives over others and should not be practiced. | 0.22 (0.57) |

| Total Rejection Attitude Mean Score | 0.44 (1.03) |

| Variable | Categories | Awareness | Acceptance | Rejection | Willingness to Register |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (S.D) | M (S.D) | M (S.D) | M (S.D) | ||

| Age | 19–30 years | 13.89 (2.76) | 17.37 (2.84) | 0.51 (1.16) | 2.51 (0.97) |

| 31–44 years | 13.88 (2.71) | 17.69 (2.59) | 0.34 (0.91) | 2.54 (0.98) | |

| t-test | t = 0.56 (ns) | t = 1.54 (ns) | t = 2.29 * | t = 0.49 (ns) | |

| Education | School | 12.22 (2.64) | 15.21 (3.84) | 1.38 (1.81) | 2.46 (0.76) |

| College | 13.22 (2.39) | 17.17 (2.50) | 0.56 (1.06) | 2.51 (0.93) | |

| University | 14.27 (2.71) | 17.89 (2.46) | 0.29 (0.81) | 2.54 (0.99) | |

| F-test | F = 22.94 *** | F = 32.56 ** | F = 38.11 (ns) | F = 0.23 (ns) | |

| Nationality | Saudi | 13.77 (2.74) | 17.35 (2.72) | 0.47 (1.07) | 2.56 (0.97) |

| Non-Saudi | 14.81 (2.53) | 18.83 (2.51) | 0.16 (0.60) | 2.26 (0.83) | |

| t-test | t = 3.14 ** | t = 4.55 *** | t = 3.91 *** | t = 2.88 * | |

| Religious Orientation | Islam | 13.85 (2.74) | 17.45 (2.74) | 0.45 (1.05) | 2.53 (0.97) |

| Hindu | 15.00 (1.86) | 18.94 (1.73) | 0.13 (0.50) | 2.38 (0.95) | |

| Christian | 14.57 (1.82) | 18.00 (2.77) | 0.00 (0.00) | 2.93 (0.91) | |

| F-test | F = 1.84 (ns) | F = 2.49 (ns) | F = 2.05 (ns) | F = 1.43 (ns) | |

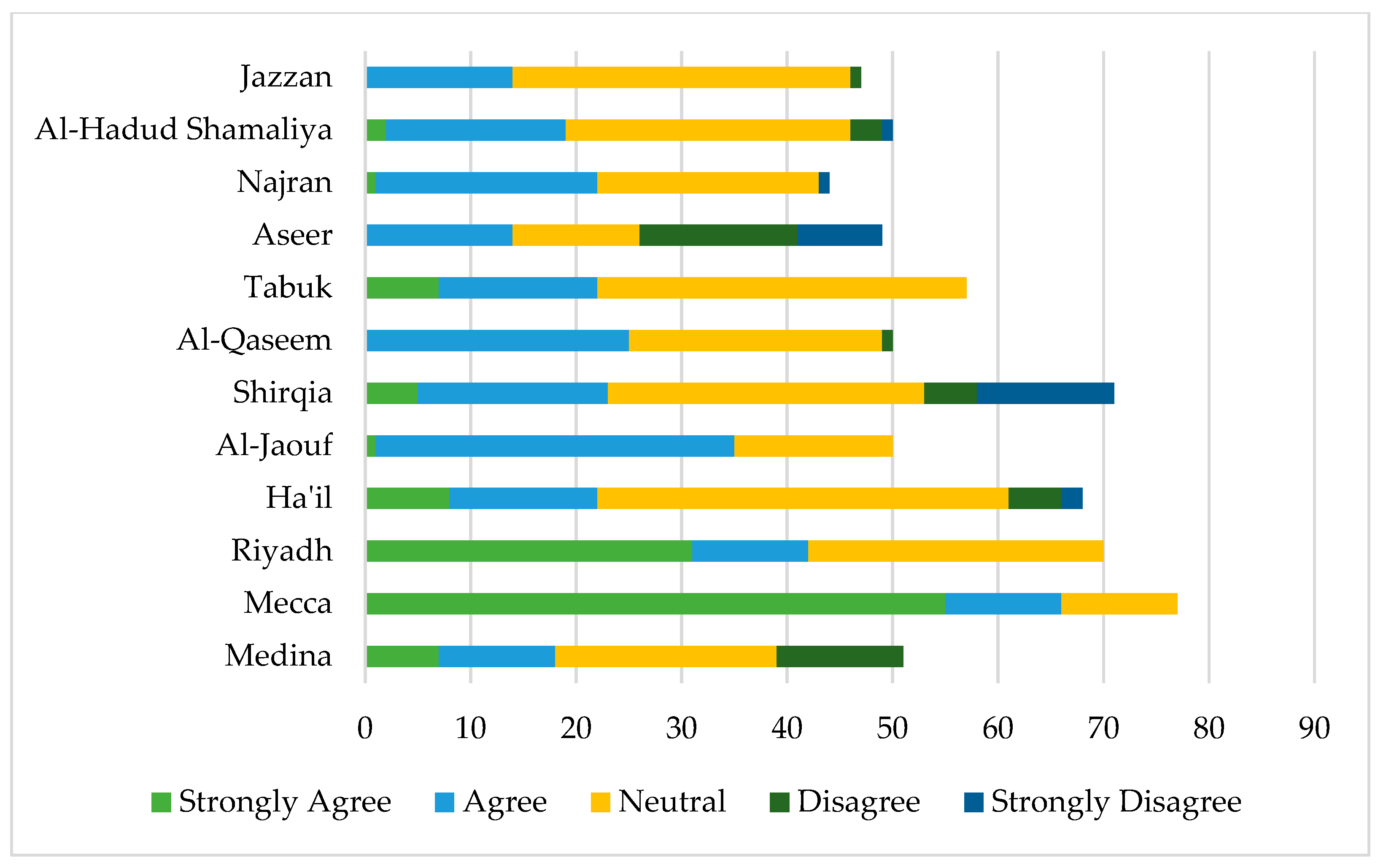

| Place of Residence | Medina | 14.88 (1.39) | 19.06 (1.17) | 0.33 (0.55) | 2.25 (0.97) |

| Mecca | 12.27 (3.23) | 16.18 (2.61) | 0.18 (0.80) | 3.57 (0.73) | |

| Riyadh | 15.01 (3.03) | 16.63 (3.02) | 0.34 (1.12) | 3.04 (0.92) | |

| Ha’il | 14.31 (3.24) | 18.01 (2.85) | 0.18 (0.66) | 2.31(0.88) | |

| Al-Jaouf | 13.38 (2.42) | 17.26 (2.92) | 0.66 (1.20) | 2.72 (0.49) | |

| Shirqia | 15.89 (1.98) | 19.42 (1.75) | 0.11 (0.66) | 1.96 (1.16) | |

| Al-Qaseem | 13.52 (2.30) | 17.64 (2.63) | 0.62 (1.44) | 2.48 (0.54) | |

| Tabuk | 13.81 (2.31) | 17.84 (2.31) | 0.25 (0.78) | 2.51 (0.71) | |

| Aseer | 14.65 (2.81) | 17.82 (2.84) | 0.20 (0.67) | 1.65 (1.07) | |

| Najran | 13.59 (1.96) | 17.23 (2.64) | 0.91 (1.27) | 2.48 (0.66) | |

| Al-Hadud Shamaliya | 13.54 (2.31) | 17.46 (2.66) | 0.56 (1.21) | 2.32 (0.74) | |

| Jazzan | 12.47 (1.55) | 16.72 (2.54) | 0.64 (1.16) | 2.28 (0.49) | |

| Al-Baha | 11.53 (1.94) | 15.37 (2.76) | 1.77 (1.01) | 2.90 (0.75) | |

| F-test | F = 12.73 *** | F = 9.86 *** | F = 7.99 *** | F = 22.14 *** |

| Variables | Categories | Awareness | Acceptance | Rejection | Willingness to Register |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (S.D) | M (S.D) | M (S.D) | M (S.D) | ||

| Sources of knowledge | Formal education | 16.92 (2.01) | 19.77 (0.82) | 0.09 (0.43) | 2.65 (1.03) |

| Social Media | 13.45 (2.14) | 17.66 (1.87) | 0.30 (0.73) | 2.57 (0.88) | |

| Online Sources | 13.90 (2.41) | 17.23 (2.41) | 0.26 (0.65) | 2.29 (1.11) | |

| Friends | 14.27 (2.25) | 18.12 (1.58) | 0.08 (0.27) | 1.77 (1.17) | |

| TV Programs | 13.32 (2.58) | 17.05 (2.41) | 0.00 (0.00) | 3.42 (0.83) | |

| F-test | F = 63.51 *** | F = 38.84 *** | F = 3.83 ** | F = 10.21 ** | |

| You or first-degree relatives underwent stem cell donation | Yes | 16.75 (2.96) | 18.75 (1.83) | 0.25 (0.46) | 3.50 (0.75) |

| No | 13.85 (2.71) | 17.49 (2.75) | 0.44 (1.04) | 2.51 (0.95) | |

| t-test | t = 2.99 * | t = 1.29 (ns) | t = 0.51 (ns) | t = 2.91 ** | |

| You or first-degree relatives underwent stem cell therapy | Yes | 16.82 (3.04) | 19.23 (1.87) | 0.23 (0.86) | 3.68 (0.13) |

| No | 13.79 (2.67) | 17.45 (2.75) | 0.45 (1.04) | 2.49 (0.36) | |

| t-test | t = 5.20 *** | t = 4.29 *** | t = 0.97 (ns) | 8.38 *** |

| Awareness | Acceptance Attitude | Rejection Attitude | Willingness to Register | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Awareness | - | 0.750 ** | −0.373 ** | 0.107 ** |

| Acceptance | 0.750 ** | - | −0.629 ** | 0.015 |

| Rejection | −0.373 ** | −0.629 ** | - | −0.085 * |

| Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | 95.0% Confidence Interval for β | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | β | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||

| (Constant) | 4.47 | 0.563 | 7.95 | 3.372 | 5.583 | |

| Age (Ref Category 31–45 years old) | 0.020 | 0.041 | 0.018 | 0.48 (ns) | −0.061 | 0.101 |

| Education (Ref Category University Education) | 0.018 | 0.083 | 0.008 | 0.21 (ns) | −0.144 | 0.180 |

| Nationality (Ref Category Saudi) | 0.547 | 0.160 | 0.176 | 3.42 ** | 0.860 | 0.233 |

| Religion (Ref Category Islam) | 0.165 | 0.215 | 0.034 | 0.76 (ns) | −0.258 | 0.588 |

| Sources of Information (Ref Category Formal Education) | 0.371 | 0.128 | 0.148 | 2.90 ** | 0.623 | 0.120 |

| Prior Direct/indirect Exposure to Stem Cell Donation | 0.445 | 0.346 | 0.049 | 1.28 (ns) | −0.233 | 1.124 |

| Prior Direct/indirect Exposure to Stem Cell Therapy | 1.065 | 0.215 | 0.191 | 4.95 *** | 0.643 | 1.486 |

| Awareness | 0.044 | 0.022 | 0.124 | 1.96 * | 0.000 | 0.087 |

| Acceptance Attitudes | −0.085 | −0.023 | −0.243 | −3.64 | −0.131 | −0.039 |

| Rejection Attitudes | −0.158 | 0.044 | −0.170 | −3.57 *** | −0.245 | −0.071 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

AL-Shammary, A.A.; Hassan, S.u.-N. Inconsistencies in Pregnant Mothers’ Attitudes and Willingness to Donate Umbilical Cord Stem Cells: A Cross-Sectional Analysis from Saudi Arabia. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3079. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12093079

AL-Shammary AA, Hassan Su-N. Inconsistencies in Pregnant Mothers’ Attitudes and Willingness to Donate Umbilical Cord Stem Cells: A Cross-Sectional Analysis from Saudi Arabia. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(9):3079. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12093079

Chicago/Turabian StyleAL-Shammary, Asma Ayyed, and Sehar un-Nisa Hassan. 2023. "Inconsistencies in Pregnant Mothers’ Attitudes and Willingness to Donate Umbilical Cord Stem Cells: A Cross-Sectional Analysis from Saudi Arabia" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 9: 3079. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12093079

APA StyleAL-Shammary, A. A., & Hassan, S. u.-N. (2023). Inconsistencies in Pregnant Mothers’ Attitudes and Willingness to Donate Umbilical Cord Stem Cells: A Cross-Sectional Analysis from Saudi Arabia. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(9), 3079. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12093079