Abstract

Background: Autologous breast reconstruction is a reliable solution for many patients after mastectomy. While this technique represents a standardized approach in many patients, patients with ptotic breasts may require a combination of procedures to achieve an aesthetically pleasing result. Methods: We reviewed the mastectomy and free-flap breast reconstruction procedures performed at our institution from 2018 to 2022 in patients with ptotic breasts. The technique used to address the ptosis was put in focus as we present the four strategies used by our reconstructive surgeons. We performed two different one-stage and two different two-stage procedures. The difference between the two-stage procedures was the way the nipple areola complex was treated (inferior dermal pedicle or free skin graft). The difference between the one-stage procedures was the time of execution of the mastopexy/breast reduction (before or after the mastectomy and autologous breast reconstruction). Results: The one-stage procedure was performed with a free NAC in three patients and with a pedicled NAC in five patients. The two-stage procedure was performed in seven patients, with six of them undergoing mastopexy before and one patient undergoing mastopexy after the bilateral mastectomy and autologous reconstruction. No flap loss or total loss of the nipple areola complex occurred. Partial NAC loss was observed in five breasts in the single-stage group without any occurrence in the double-stage group. Conclusions: While both one- and two-stage procedures were performed in a safe fashion with satisfactory results at our institution, larger trials are required to determine which procedure may yield the best possible outcomes. These outcomes should also include oncological safety and patient-reported outcomes.

1. Introduction

There is an increasing number of identified BReast CAncer (BRCA) 1 or 2 pathogenic variant (PV) carriers [1]. This can be attributed to universal genetic tumor testing in ovarian cancer patients [2], better diagnostic tools, increased referral rates, and patient awareness. The demand for prophylactic mastectomy in such patients leads to an increase in the need for breast reconstruction procedures.

Hartmann et al., showed that prophylactic mastectomy can considerably reduce the incidence of breast cancer in women with a high risk of breast cancer based on family history [3]. The superiority of nipple-sparing mastectomy (NSM) compared to skin-sparing mastectomy (SSM) regarding psychosocial and sexual well-being, body image, feeling of mutilation, and satisfaction with the appearance of the nipple has been demonstrated previously [4,5,6]. It should also be noted that there are studies which do not show any significant difference between NSM and SSM with reconstruction of the nipple areola complex (NAC) [7].

The complexity of surgery planning increases in patients with ptotic breasts requiring a mastectomy, as the surgical management of these patients often requires extensive tissue removal and reconstruction. Mastectomy with autologous reconstruction has emerged as a viable surgical approach in such cases, as it allows for the removal of breast tissue while preserving a natural breast shape and contour. In the literature, reconstruction of ptotic breasts is often associated with increased surgical complication rates, particularly for NAC necrosis [8,9]. These complications can result in poor surgical outcomes, such as asymmetry, poor cosmetic results, and patient dissatisfaction. As a result, the management of large and ptotic breasts requires specialized surgical skills and expertise. However, some authors argue in favor of performing reconstructions regardless of breast characteristics using several algorithms [10].

A modified nipple-sparing mastectomy with a periareolar pexy has been described for women with medium-sized breasts [11]. Women with large and ptotic breasts represent a challenging subgroup of patients. A thorough understanding of surgical techniques, outcomes, and associated complications is necessary to achieve optimal surgical outcomes in these patients. The aim of a reconstructive surgeon is not only to restore the lost volume and skin after mastectomy, but also to provide an aesthetically pleasing result. This can be a difficult task, especially in cases where a mastopexy is necessary. Similar to augmentation mastopexy, special attention must be given to preparing an accurate surgical plan. In ptotic breasts, the surgeon has the choice to perform the augmentation and the mastopexy as a one-stage or as a two-stage procedure. The same applies to breast reconstruction procedures in ptotic breasts.

Patients with large and ptotic breasts or post-bariatric patients with ptotic breasts who undergo a breast reconstruction after mastectomy, either due to breast cancer or prophylactically, are candidates for these kinds of procedures. The reports on autologous breast reconstruction of large and ptotic breasts found in the literature are limited and there is no clear recommendation on which procedure to use.

This paper aims to review the current literature on prophylactic mastectomy and autologous reconstruction in patients with large and ptotic breasts. It also aims to describe our experience with four options of autologous breast reconstruction using the DIEP flap after prophylactic mastectomy in this challenging patient population, with a focus on surgical techniques and associated complications.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was approved by the local ethics committee.

We conducted a retrospective study by reviewing the electronic medical records of our institution. We reviewed the mastectomy and breast reconstruction procedures with a free flap performed at our institution between 2018 and 2022. All patients with ptotic breasts grade 2 and 3 after Regnault [12] who underwent a mastectomy, autologous breast reconstruction with DIEP flap and breast reduction or mastopexy were selected for further analysis and were included in the study. The technique used to address the ptosis was put in focus and we present each procedure used by our reconstructive surgeons. We provide details regarding the patient characteristics, surgery, and postoperative complications.

2.1. Indications for the Planned Procedures

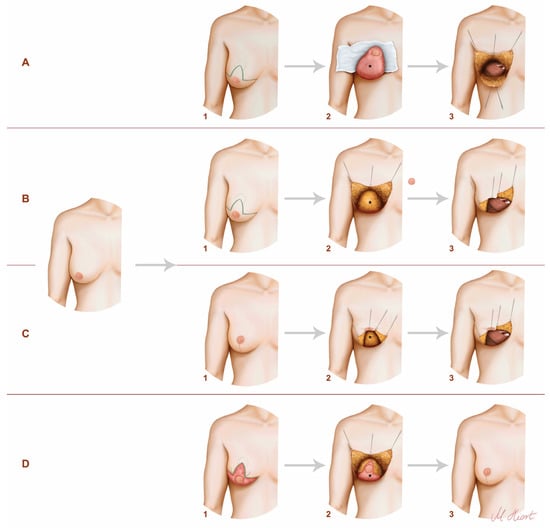

All patients with grade 2 or 3 ptosis were treated with one of the following procedures (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The techniques used in our clinic. The illustration on the left demonstrates the preoperative condition of the patients. (A) One-staged procedure with inferior pedicled NAC—1: preoperative markings; 2: intraoperatively; 3: exposure of the internal mammary vessels (IMV); *: inferior dermal pedical. (B) One staged procedure with free NAC skin graft—1: preoperative markings; 2: intraoperatively; 3: exposure of the IMV; *: breast tissue. (C) Two-staged procedure—mastopexy before mastectomy and reconstruction—1: breast after mastopexy/reduction; 2: mastectomy; 3: exposure of the IMV; *: breast tissue. (D) Two-staged procedure—mastopexy/reduction after mastectomy and reconstruction—1: de-epithelialized breast after reconstruction; 2: mastopexy/reduction; 3: postoperatively; *: DIEP flap.

2.2. Surgical Technique

All included breasts underwent both mastectomy and autologous breast reconstruction. The mastectomies were performed by multiple plastic surgeons at our institution. Wise pattern excision incision lines were marked preoperatively on a standing patient. The surgeries were performed in a two-team approach.

2.2.1. One-Stage Procedures

- Pedicled nipple areola complex (NAC)

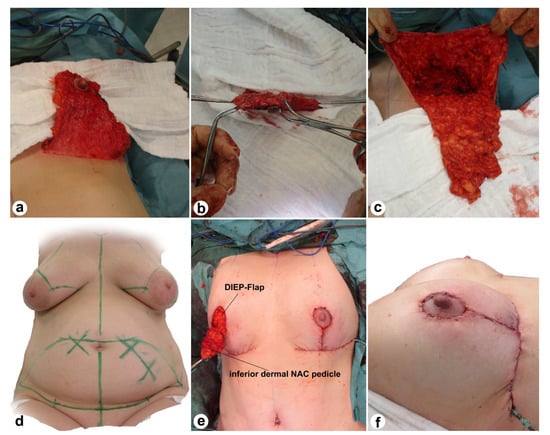

During this procedure, the mastectomy, autologous breast reconstruction, and mastopexy were executed as a one-stage procedure. A triangular inferior dermal pedicle was dissected with a retroareolar thickness of 0.5 cm and a thickness of 1 cm for the rest of the pedicle (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Intraoperative view (a–c,e) and markings (d) of the Wise pattern excision and the inferior dermal NAC pedicle. The last picture (f) demonstrates the intraoperative result after bilateral Wise pattern excision with pedicled NAC, mastectomy, and breast reconstruction with DIEP.

- Free skin graft

The Wise pattern excision lines are the same as above. However, during this procedure no inferior dermal flap was dissected. Instead, the NAC was grafted as a free skin graft.

2.2.2. Two-Stage Procedures

- Breast reduction first

In this approach, patients received a breast reduction/mastopexy during the first surgery. The second surgery, which involved a mastectomy and autologous breast reconstruction, was performed 7.4 ± 3.8 months (range 4.6–16.7 months) after the reduction/mastopexy.

- Mastectomy and autologous breast reconstruction first

In this approach, the patient received a bilateral mastectomy and autologous breast reconstruction with a DIEP flap through inframammary fold incisions during the first surgery. The mastopexy was then performed 11 months after the first surgery.

3. Results

Patient characteristics, surgery details, and postoperative complications are presented in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics (Mean ± SD).

Table 2.

Surgery and postoperative details (Mean ± SD).

3.1. One-Stage Procedures

3.1.1. Pedicled Nipple Areola Complex (NAC) (Figure 3)

Five patients received 10 flaps with a mean surgery time of 320.8 ± 30.0 min. The time to ambulation for this group was 8.0 ± 2.0 days. Partial NAC necrosis occurred in two patients (three breasts, 30.0%), with one patient requiring a revision operation for necrosis excision (Figure 4). The third partial necrosis was managed conservatively. Both patients showed satisfactory results during follow-up. One breast (10.0%) required a revision due to arterial thrombosis, with the flap being saved after anastomosis revision. The NAC involved showed a partial necrosis (right breast Figure 4). Wound dehiscence occurred in two breasts (20.0%) of the same patient, and one patient (20.0%) experienced a donor site infection. No cases of fat necrosis were observed.

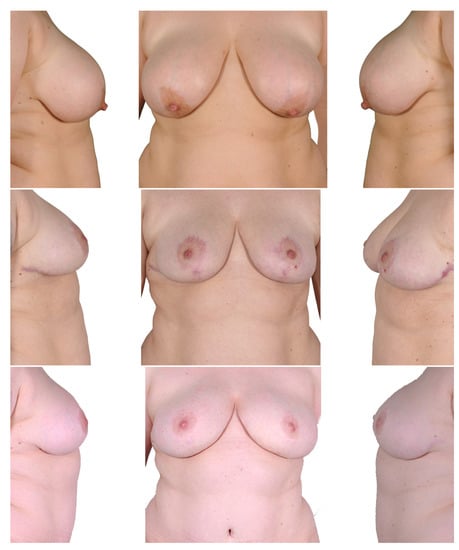

Figure 3.

One-stage procedure—bilateral mastectomy, mastopexy with inferior dermal NAC pedical, DIEP. Top row: preoperatively; bottom row: postoperatively.

Figure 4.

One-stage mastectomy, Wise pattern skin excision with inferior dermal NAC pedicle. From left to right: preoperatively/bilateral partial NAC necrosis 16 days after initial surgery/4 months after necrosis excision and 6 months after initial surgery.

3.1.2. Free Skin Graft (Figure 5)

Three patients received a total of six flaps, with a mean surgery time of 309.0 ± 39.0 min. The time to ambulation for this group was 6.7 ± 1.2 days. One patient (two breasts, 33.3%) experienced a partial NAC necrosis which was managed conservatively. No anastomosis revision was required. One breast (16.7%) showed signs of fat necrosis. No wound dehiscence at the breast or donor site complications was observed.

Figure 5.

One-stage procedure—bilateral mastectomy, mastopexy with free skin graft, DIEP. Top row: preoperatively; bottom row: postoperatively.

3.2. Two-Stage Procedures

3.2.1. Breast Reduction First (Figure 6)

Six patients received 11 flaps. In one case, the second flap was not transferred due to insufficient perfusion.

The total surgery time for the mastopexy was 125.0 ± 19.9 min, and for the bilateral mastectomy and autologous breast reconstruction it was 320.2 ± 69.9 min. The time to ambulation was 2.7 ± 1.2 days after the mastopexy and 6.4 ± 1.7 after the mastectomy and breast reconstruction. There were no cases of total or partial NAC necrosis. No anastomosis revision was necessary. Two breasts (18.0%) on two patients showed a wound dehiscence, and four patients (66.7%) experienced a donor site complication. Three of them showed a wound dehiscence and one patient had a donor site seroma and infection.

Figure 6.

Two-stage procedure—1. breast reduction, 2. bilateral mastectomy and DIEP. Top row: preoperatively; middle row: postoperatively after breast reduction; bottom row: postoperatively after mastectomy and autologous breast reconstruction.

3.2.2. Mastectomy and Autologous Breast Reconstruction First (Figure 7)

Only one patient underwent this procedure due to an unsatisfactory result after the initial surgery. There was no flap loss and no occurrence of total loss of the nipple areola complex. One breast (50%) showed signs of fat necrosis. No anastomosis revision was necessary. No breast wound dehiscence or donor site complication occurred in this case.

Figure 7.

Two-stage procedure—1. bilateral mastectomy and DIEP, 2. mastopexy. Top row: preoperatively; middle row: postoperatively after mastectomy and autologous breast reconstruction; bottom row: postoperatively after mastopexy.

4. Discussion

Whether concerning post bariatric patients or patients with large and ptotic breasts, reconstructive surgeons face several challenges when planning a bilateral prophylactic mastectomy and autologous breast reconstruction. This group of patients has long been considered high-risk, due to an increased risk of NAC and skin flap necrosis [13,14]. A study of 2023 NSMs showed that patients with ptosis may exhibit poorer postoperative results [15].

The operative planning and decision-making process regarding one- or two-stage reconstruction and whether to use a pedicled or free NAC graft are crucial in achieving an aesthetically pleasing outcome. Although the primary goal is to remove at-risk breast tissue, the long-term cosmetic outcome has also been demonstrated to have a strong impact on patients’ quality of life [6,16,17,18,19,20,21]. The aim of this paper is to provide a review of the current literature on prophylactic mastectomy and autologous reconstruction in patients with large and ptotic breasts and an overview of the techniques used at our institution, which may help inform clinical decision-making and improve the quality of care for this challenging group of patients. According to the Consensus Conference of the Oncoplastic Breast Consortium on nipple-sparing mastectomy in women with cup size ≥ C and ptosis ≥ grade 2 without other risk factors for nipple necrosis, NSM can be performed with skin reduction and nipple–areola pedicles. This is regardless of the breast reconstruction technique, or with skin reduction and free-nipple grafting [22].

The method most frequently addressed in the literature for reconstruction of large and ptotic breasts is heterologous reconstruction using breast implants, either as a one-stage procedure using a permanent implant or as a two-stage procedure using a tissue expander which is later replaced by a permanent implant [8,23,24,25,26,27,28].

Despite rising evidence of higher long-term satisfaction and increased health-related quality of life (HR-QoL) linked with autologous procedures, the number of patients undergoing this kind of reconstruction has decreased in the United States [29].

Due to greater psychosocial and sexual well-being, more natural characteristics of the breast, and better performance in terms of postoperative radiation, however, autologous reconstruction remains the gold standard for certain cases and should be preferred if appropriate surgical skills and anatomical conditions are given.

The two-stage procedure has been discussed in the past [9,30]. Alperovic et al., showed that in patients with previous reduction mammaplasty or mastopexy, nipple-sparing mastectomy can be considered safe if one year or more has passed since surgery. In shorter time periods, they recommend selectively using indocyanine green (ICG) to evaluate perfusion of the mastectomy flap and NAC intraoperatively. Reconstructive outcomes of nipple-sparing mastectomy in patients with mastopexy or breast reduction in history are comparable to those who underwent nipple-sparing mastectomy only [31].

Komorowska-Timek et al., have also demonstrated the efficacy of ICG perfusion mapping in predicting tissue necrosis of the mastectomy flaps [32].

This can be used in cases of one-stage reconstruction with an inferior pedicle if vascularization of the NAC is uncertain. We suggest the conversion from pedicled NAC to free-skin graft if there is uncertainty about adequate vascularization.

Tondu et al., have also described a two-stage procedure of mastectomy and heterologous breast reconstruction, with the first stage being an inferior pedicle breast reduction with Wise pattern skin reduction and expander implantation [24]. A two-stage approach with a mastopexy following a mastectomy and free flap reconstruction was also described previously [33,34]. In 1985, Hester reported on breast reduction with a central pedicle [35].

DellaCroce et al., have conducted a study on 70 patients with large and ptotic breasts, in which they performed NSM and immediate autologous reconstruction initially followed by a second-staged mastopexy using a central pedicle [34]. They achieved high patient satisfaction with low complication rates and no cases of nipple–areola complex necrosis. The authors advocate for a two-stage procedure, especially because NAC repositioning requires a robust nipple–areola complex revascularization from an underlying well-perfused flap before interrupting the surrounding cutaneous blood supply of the NAC. We had a similar experience in the one case we performed using this technique, which resulted in a satisfied patient. This method could potentially be used not only in patients with large and ptotic breasts but also in patients with asymmetry or an unsatisfactory result after a DIEP flap reconstruction, as an alternative or additional tool to lipofilling.

Due to the prolonged duration and increased complexity of the combined operations, Schneider et al., also advocate a two-stage procedure and recommend performing a mastopexy or breast reduction simultaneously with secondary procedures often required following free flap reconstructions [33]. Interestingly, we did not find an increased surgery time in one-stage procedures compared to two-stage procedures in our study.

Despite the good results, the main disadvantage of two-stage procedures is the need for two major surgeries. Minimizing the number of operations would be desirable.

Several surgical techniques have been developed to address this challenge. Gibson presented a subcutaneous mastectomy technique using an inferior pedicle back in 1979 [36]. Woods discussed the topic of NSM and simultaneous mastopexy with inferior and superior pedicle in 1987 [37]. Kontos et al., presented a mastopexy technique with two skin flaps and a resulting horizontal scar in the middle of the breast as a one-stage procedure in combination with a mastectomy and immediate implant reconstruction [38]. The inferior dermal pedicle was also described by other authors as a basis for an implant-based reconstruction after mastectomy [27,39,40].

Surgical delay was also described to facilitate pedicled NSM and reconstruction in the ptotic breast [41].

The thickness of the mastectomy skin flap plays a crucial role for skin viability. Larson et al., stated that using the subcutaneous layer present in most breasts as a guide for elevating the skin flaps can achieve both oncologic safety and viable skin flaps [42].

Davies et al., reported higher skin-sparing mastectomy flap morbidity in breasts where the mastectomy was performed using Wise pattern or tennis pattern incisions. The main complication associated with the Wise incision was found to be wound dehiscence, especially at the T-junction (32%) [43].

Egan et al., highlighted that hypopigmentation, depigmentation, partial graft loss and loss of nipple projection are complications which are not rare after free-nipple areolar grafting. However, these complications were not statistically correlated with NAC aesthetic or overall aesthetic rate in their study [44].

There are only a few reports on one-stage autologous reconstruction in large and ptotic breasts. In a study by Pontell et al., bilateral NSM with a simultaneous reduction mastopexy and immediate reconstruction using a DIEP flap or expander were performed in eight patients with large ptotic breasts. To decrease the risk of NAC necrosis, wide, inferior, epithelialized pedicles were used for reconstruction [8]. However, they reported on a high number of nicotine-associated NAC necrosis occurrences while observing a small sample size. In a recent study of Rose et al., buried autologous breast reconstruction (BARB) flaps were compared with non-buried flaps in one-stage procedures after mastectomy. In the case of large and ptotic breasts, Wise pattern reduction mastectomy was performed with or without nipple preservation on an inferior pedicle or as a free-nipple graft. The authors concluded that buried free flaps are safe and reliable with lower revision rates than those with cutaneous paddles. They recommended single-stage reconstruction regardless of breast characteristics [10].

Advances in mastectomy techniques lead to better aesthetic results. Reconstructive options have improved substantially, making it possible to achieve a good cosmetic result in women with large and ptotic breasts. The choice of the most suitable technique for prophylactic mastectomy and reconstruction in this patient group depends not only on the surgeon’s experience and preference but also on various factors, such as the patient’s anatomy, comorbidities and aesthetic goals. The oncological safety of a pedicled NSM compared to a free full-thickness skin graft can be debated, since the former preserves a small amount of breast tissue, although located in an easily palpable area.

Avoiding complications such as necrosis of the nipple–areola complex or skin flap necrosis remains one of the main concerns when performing NSM on ptotic breasts. Careful surgical planning is crucial to achieving optimal outcomes.

One limitation of the study was its retrospective nature, as well as the small number of cases included.

5. Conclusions

There are a number of different options for performing bilateral prophylactic mastectomy and autologous breast reconstruction in patients with large and ptotic breasts. Mastopexy can be performed before, with, or after mastectomy and autologous reconstruction with good surgical outcomes. Larger studies with longer follow-up periods are needed to fully assess the oncological safety and patient satisfaction associated these procedures.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.V., T.H., P.W. and M.K.; formal analysis, C.V.; investigation, C.V.; project administration, M.K.; resources, S.W., T.H., P.W. and M.K.; writing—original draft preparation, C.V. and M.B.; writing—review and editing, S.W., T.H., P.W. and M.K.; visualization, C.V.; validation, C.V., T.H., P.W. and M.K.; supervision, M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethic Committee Name: Ethics Committee of the Medical Association Westphalia-Lippe and the Westphalian Wilhelms University. Approval code: 2020-779-f-S. Approval Date: 6 February 2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Van Bommel, M.H.D.; Inthout, J.; Veldmate, G.; Kets, C.M.; De Hullu, J.A.; Van Altena, A.M.; Harmsen, M.G. Contraceptives And Cancer Risks in Brca1/2 Pathogenic Variant Carriers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update 2022, 29, 197–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vos, J.R.; Fakkert, I.E.; De Hullu, J.A.; Van Altena, A.M.; Sie, A.S.; Ouchene, H.; Willems, R.W.; Nagtegaal, I.D.; Jongmans, M.C.J.; Mensenkamp, A.R.; et al. Universal Tumor Dna Brca1/2 Testing of Ovarian Cancer: Prescreening Parpi Treatment and Genetic Predisposition. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2020, 112, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartmann, L.C.; Schaid, D.J.; Woods, J.E.; Crotty, T.P.; Myers, J.L.; Arnold, P.G.; Petty, P.M.; Sellers, T.A.; Johnson, J.L.; Mcdonnell, S.K.; et al. Efficacy of Bilateral Prophylactic Mastectomy in Women with a Family History of Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 340, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.H.; Scott, A.M.; Price, A.N.; Miller, H.C.; Klassen, A.F.; Jhanwar, S.M.; Mehrara, B.J.; Disa, J.J.; Mccarthy, C.; Matros, E.; et al. Psychosocial And Sexual Well-Being Following Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy and Reconstruction. Breast J. 2016, 22, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Didier, F.; Radice, D.; Gandini, S.; Bedolis, R.; Rotmensz, N.; Maldifassi, A.; Santillo, B.; Luini, A.; Galimberti, V.; Scaffidi, E.; et al. Does Nipple Preservation in Mastectomy Improve Satisfaction with Cosmetic Results, Psychological Adjustment, Body Image and Sexuality? Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2009, 118, 623–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metcalfe, K.A.; Cil, T.D.; Semple, J.L.; Li, L.D.; Bagher, S.; Zhong, T.; Virani, S.; Narod, S.; Pal, T. Long-Term Psychosocial Functioning In Women With Bilateral Prophylactic Mastectomy: Does Preservation Of The Nipple-Areolar Complex Make A Difference? Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2015, 22, 3324–3330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Verschuer, V.M.; Mureau, M.A.; Gopie, J.P.; Vos, E.L.; Verhoef, C.; Menke-Pluijmers, M.B.; Koppert, L.B. Patient Satisfaction and Nipple-Areola Sensitivity after Bilateral Prophylactic Mastectomy and Immediate Implant Breast Reconstruction in a High Breast Cancer Risk Population: Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy Versus Skin-Sparing Mastectomy. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2016, 77, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontell, M.E.; Saad, N.; Brown, A.; Rose, M.; Ashinoff, R.; Saad, A. Single Stage Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy and Reduction Mastopexy in the Ptotic Breast. Plast. Surg. Int. 2018, 2018, 9205805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spear, S.L.; Rottman, S.J.; Seiboth, L.A.; Hannan, C.M. Breast Reconstruction Using A Staged Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy Following Mastopexy or Reduction. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2012, 129, 572–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, V.; Cooper, L.; Pafitanis, G.; Hogben, K.; Sharma, A.; Din, A.H. Single-Stage Buried Autologous Breast Reconstruction (BABR). J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2022, 75, 2960–2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivolin, A.; Kubatzki, F.; Marocco, F.; Martincich, L.; Renditore, S.; Maggiorotto, F.; Magistris, A.; Ponzone, R. Nipple-Areola Complex Sparing Mastectomy with Periareolar Pexy for Breast Cancer Patients with Moderately Ptotic Breasts. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2012, 65, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regnault, P. Breast Ptosis. Definition and Treatment. Clin. Plast. Surg. 1976, 3, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tondu, T.; Hubens, G.; Tjalma, W.A.; Thiessen, F.E.; Vrints, I.; Van Thielen, J.; Verhoeven, V. Breast Reconstruction after Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy in the Large and/or Ptotic Breast: A Systematic Review Of Indications, Techniques, and Outcomes. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2020, 73, 469–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endara, M.; Chen, D.; Verma, K.; Nahabedian, M.Y.; Spear, S.L. Breast Reconstruction Following Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy: A Systematic Review of the Literature with Pooled Analysis. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2013, 132, 1043–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vita, R.; Zoccali, G.; Buccheri, E.M.; Costantini, M.; Botti, C.; Pozzi, M. Outcome Evaluation after 2023 Nipple-Sparing Mastectomies: Our Experience. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2017, 139, 335e–347e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siqueira, H.F.F.; Teixeira, J.L.A.; Lessa Filho, R.D.S.; Hora, E.C.; Brasileiro, F.F.; Borges, K.S.; Brito, É.; Lima, M.S.; Marques, A.D.; Moura, A.R.; et al. Patient Satisfaction and Quality of Life in Breast Reconstruction: Assessment of Outcomes of Immediate, Delayed, and Nonreconstruction. BMC Res. Notes 2020, 13, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghazal, S.K.; Fallowfield, L.; Blamey, R.W. Does Cosmetic Outcome from Treatment of Primary Breast Cancer Influence Psychosocial Morbidity? Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 1999, 25, 571–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heil, J.; Czink, E.; Golatta, M.; Schott, S.; Hof, H.; Jenetzky, E.; Blumenstein, M.; Maleika, A.; Rauch, G.; Sohn, C. Change of Aesthetic and Functional Outcome over Time and Their Relationship to Quality of Life after Breast Conserving Therapy. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2011, 37, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waljee, J.F.; Hu, E.S.; Ubel, P.A.; Smith, D.M.; Newman, L.A.; Alderman, A.K. Effect of Esthetic Outcome after Breast-Conserving Surgery on Psychosocial Functioning and Quality of Life. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 3331–3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiraishi, M.; Sowa, Y.; Tsuge, I.; Kodama, T.; Inafuku, N.; Morimoto, N. Long-Term Patient Satisfaction and Quality of Life Following Breast Reconstruction Using the Breast-Q: A Prospective Cohort Study. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 815498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocquyt, V.F.; Blondeel, P.N.; Depypere, H.T.; Van De Sijpe, K.A.; Daems, K.K.; Monstrey, S.J.; Van Belle, S.J. Better Cosmetic Results and Comparable Quality of Life after Skin-Sparing Mastectomy and Immediate Autologous Breast Reconstruction Compared to Breast Conservative Treatment. Br. J. Plast. Surg. 2003, 56, 462–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, W.P.; Haug, M.; Kurzeder, C.; Bjelic-Radisic, V.; Koller, R.; Reitsamer, R.; Fitzal, F.; Biazus, J.; Brenelli, F.; Urban, C.; et al. Oncoplastic Breast Consortium Consensus Conference on Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2018, 172, 523–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Mufarrej, F.M.; Woods, J.E.; Jacobson, S.R. Simultaneous Mastopexy in Patients Undergoing Prophylactic Nipple-Sparing Mastectomies and Immediate Reconstruction. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2013, 66, 747–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tondu, T.; Thiessen, F.; Hubens, G.; Tjalma, W.; Blondeel, P.; Verhoeven, V. Delayed Two-Stage Nipple Sparing Mastectomy and Simultaneous Expander-To-Implant Reconstruction of the Large and Ptotic Breast. Gland Surg. 2022, 11, 524–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammond, D.C.; Little, A.K. The Role Of Premastectomy Mastopexy and Breast Reduction in the Reconstruction of the Enlarged or Ptotic Breast. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2022, 150, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazar, S.; Bengur, F.B.; Altinkaya, A.; Kara, H.; Uras, C. Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy and Immediate Implant-Based Reconstruction with or Without Skin Reduction in Patients with Large Ptotic Breasts: A Case-Matched Analysis. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2021, 45, 956–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochlin, D.H.; Nguyen, D.H. Deepithelialized Skin Reduction Preserves Skin and Nipple Perfusion in Immediate Reconstruction of Large and Ptotic Breasts. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2018, 81, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruccia, M.; Elia, R.; Gurrado, A.; Moschetta, M.; Nacchiero, E.; Bolletta, A.; Testini, M.; Giudice, G. Skin-Reducing Mastectomy and Pre-Pectoral Breast Reconstruction in Large Ptotic Breasts. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2020, 44, 664–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchal, H.; Matros, E. Current Trends in Postmastectomy Breast Reconstruction. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2017, 140, 7s–13s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momeni, A.; Kanchwala, S.; Sbitany, H. Oncoplastic Procedures in Preparation For Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy and Autologous Breast Reconstruction: Controlling the Breast Envelope. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2020, 145, 914–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alperovich, M.; Tanna, N.; Samra, F.; Blechman, K.M.; Shapiro, R.L.; Guth, A.A.; Axelrod, D.M.; Choi, M.; Karp, N.S. Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy in Patients with a History of Reduction Mammaplasty or Mastopexy: How Safe Is It? Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2013, 131, 962–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komorowska-Timek, E.; Gurtner, G.C. Intraoperative Perfusion Mapping with Laser-Assisted Indocyanine Green Imaging Can Predict and Prevent Complications in Immediate Breast Reconstruction. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2010, 125, 1065–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, L.F.; Chen, C.M.; Stolier, A.J.; Shapiro, R.L.; Ahn, C.Y.; Allen, R.J. Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy and Immediate Free-Flap Reconstruction in the Large Ptotic Breast. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2012, 69, 425–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dellacroce, F.J.; Blum, C.A.; Sullivan, S.K.; Stolier, A.; Trahan, C.; Wise, M.W.; Duracher, D. Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy and Ptosis: Perforator Flap Breast Reconstruction allows Full Secondary Mastopexy with Complete Nipple Areolar Repositioning. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2015, 136, 1e–9e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hester, T.R.; Bostwick, J.; Miller, L.; Cunningham, S.J. Breast Reduction Utilizing the Maximally Vascularized Central Breast Pedicle. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1985, 76, 890–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, E.W. Subcutaneous Mastectomy Using an Inferior Nipple Pedicle. Aust. N. Z. J. Surg. 1979, 49, 559–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woods, J.E. Detailed Technique of Subcutaneous Mastectomy with and Without Mastopexy. Ann. Plast. Surg. 1987, 18, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontos, M.; Lanitis, S.; Constantinidou, A.; Sakarellos, P.; Vagios, E.; Tampaki, E.C.; Tampakis, A.; Fragoulis, M. Nipple-Sparing Skin-Reducing Mastectomy with Reconstruction for Large Ptotic Breasts. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2020, 73, 690–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oven, S.D.; Scarlett, W.L. Reconstruction Of Large Ptotic Breasts after Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy: A Modified Buttonhole Technique. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2020, 85, 233–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broer, N.; Narayan, D.; Lannin, D.; Grube, B. A Novel Technique For Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy and Immediate Reconstruction in Patients with Macromastia. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2010, 126, 89e–92e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, J.C.; Skowronksi, P.P. Surgical Delay Facilitates Pedicled Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy and Reconstruction in the Ptotic Patient. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2016, 4, E735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, D.L.; Basir, Z.; Bruce, T. Is Oncologic Safety Compatible with a Predictably Viable Mastectomy Skin Flap? Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2011, 127, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, K.; Allan, L.; Roblin, P.; Ross, D.; Farhadi, J. Factors Affecting Post-Operative Complications Following Skin Sparing Mastectomy with Immediate Breast Reconstruction. Breast 2011, 20, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egan, K.G.; Lai, E.; Holding, J.; Butterworth, J.A. A Comparative Analysis of Outcomes of Free Nipple Areolar Grafting in Autologous Breast Reconstruction. J. Reconstr. Microsurg. 2021, 37, 458–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).