Intramural Hematoma of Gastrointestinal Tract in People with Hemophilia A and B

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Brief Introduction of Intramural Hematoma

1.2. Main Structure of Our Review—Started from One Real-World Case

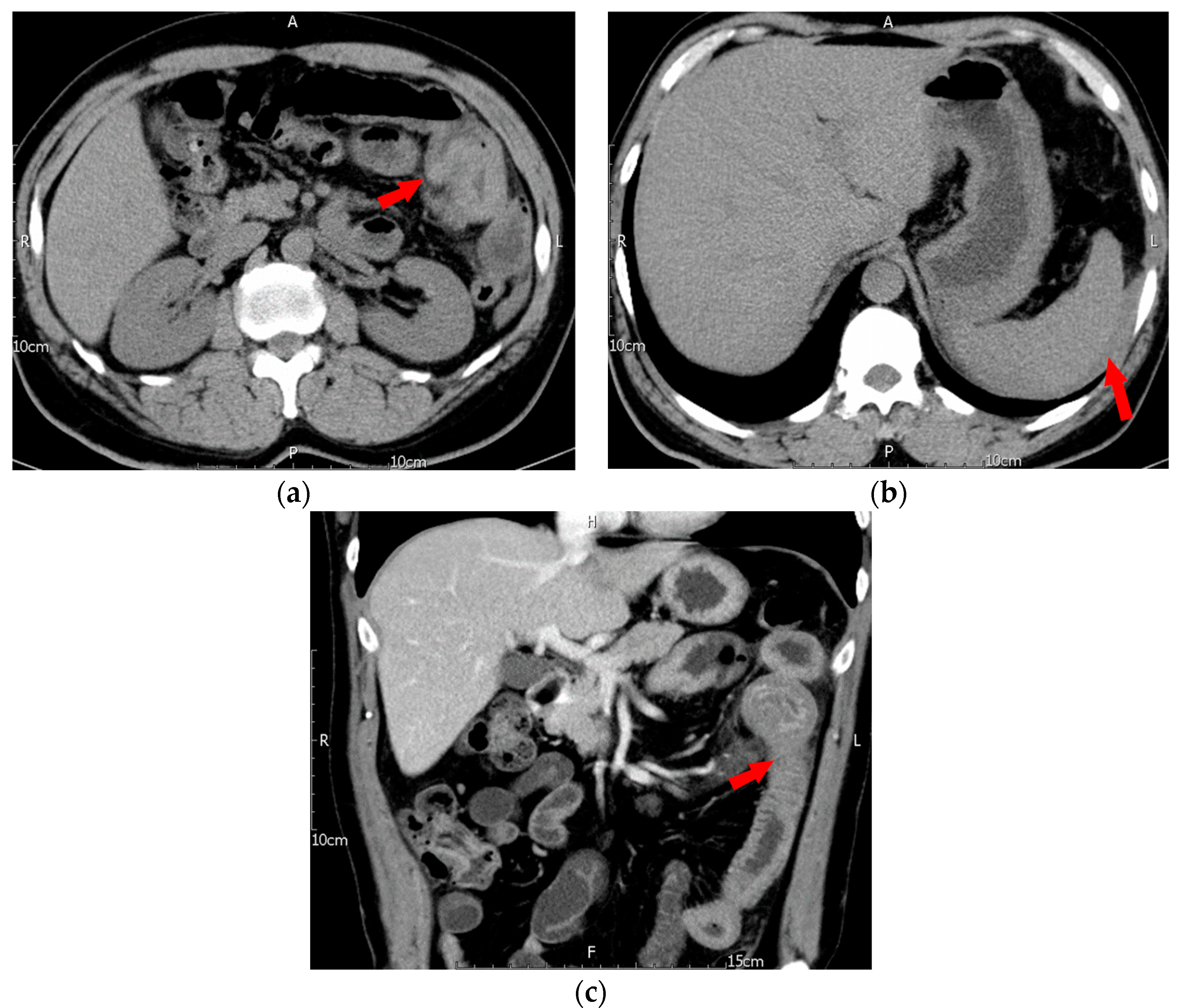

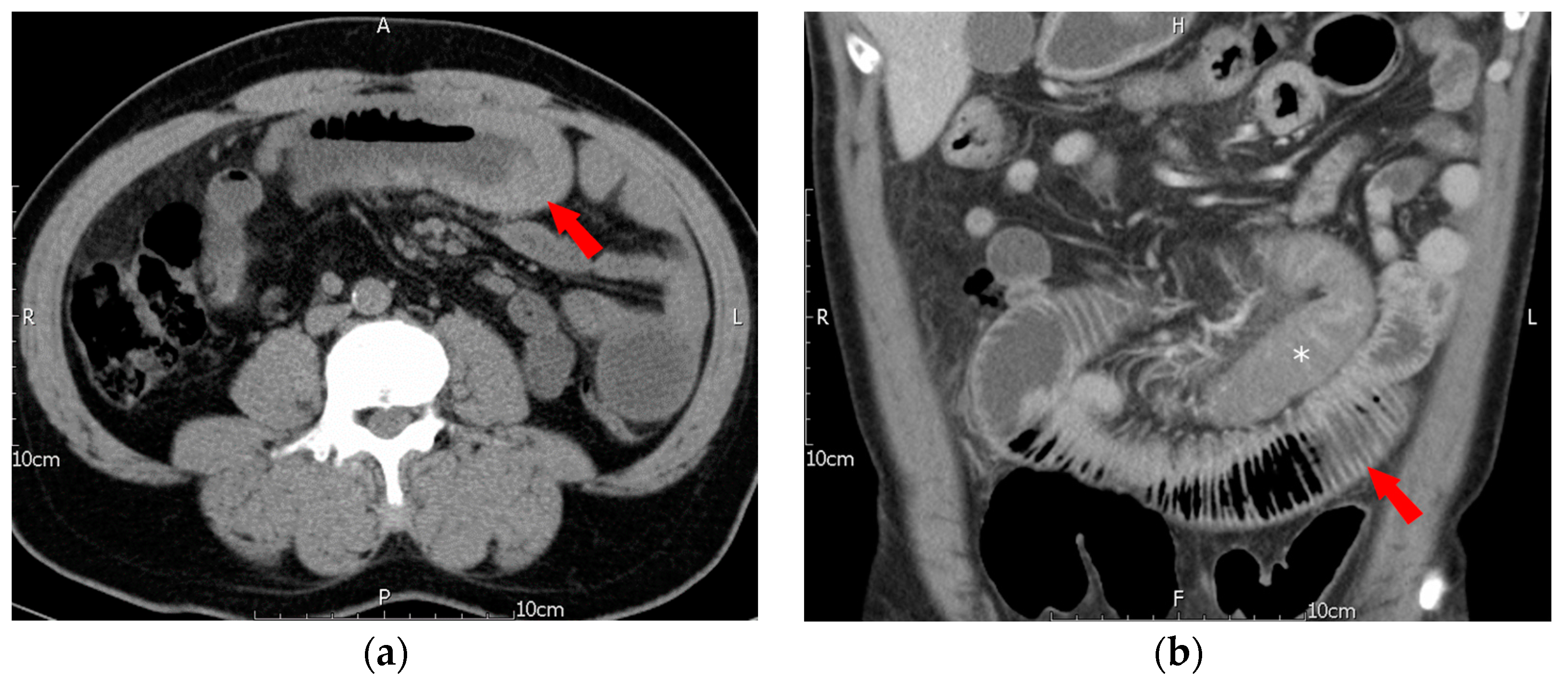

2. Case Description

3. Materials and Methods

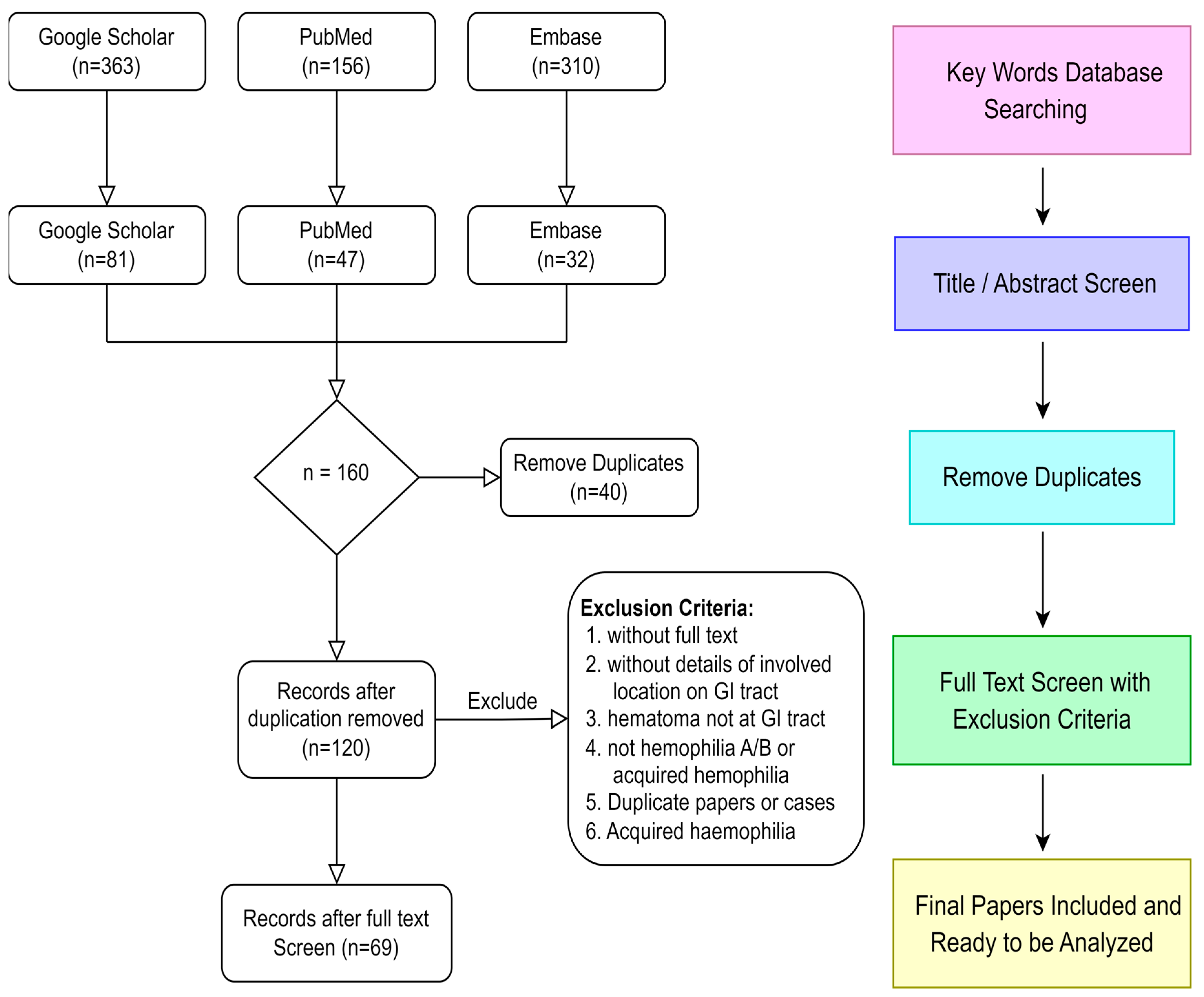

3.1. Data Sources, Searches, and Study Selection

3.2. Clinical Parameters and Statistical Analysis

3.3. Limitations

4. Results

4.1. Clinical Characteristics of the Overall Selected Cases

4.2. Prevalence of Intramural Hematoma in Hemophilia A and B

4.3. Comparisons between Inhibitor and Non-Inhibitor Groups

4.4. Clinical Features of Different Involved Sites

4.5. Comparison between Children and Adults

4.6. Comparison between Recovery and Mortality groups

4.7. Clinical Features of Intramural Hematoma-Related Intussusception

5. Discussion

5.1. Pathological Mechanism

5.2. Clinical Manifestations

5.3. Laboratory Findings

5.4. Image Findings

5.5. Intramural Hematoma-Related Intussusception

6. Future Directions

6.1. Management for Intramural Hematoma in PWH

6.2. Recurrence and Prophylaxis

6.3. For More Detailed Information

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Salma, F.; Soukaina, W. Conservative Management of a Jejuno-Jejunal Intussusception in a Patient with Severe Haemophilia A. Curr. Health Sci. J. 2021, 47, 462–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delibegovic, M.; Alispahic, A.; Gazija, J.; Mehmedovic, Z.; Mehmedovic, M. Intramural Haemorrhage and Haematoma as the Cause of Ileus of the Small Intestine in a Haemophiliac. Med. Arch. 2015, 69, 206–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramadan, K.M.; Lowry, J.P.; Wilkinson, A.; McNulty, O.; McMullin, M.F.; Jones, F.G. Acute intestinal obstruction due to intramural haemorrhage in small intestine in a patient with severe haemophilia A and inhibitor. Eur. J. Haematol. 2005, 75, 164–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prieto, H.M.M.; Perez, C.P.; Bermejo, J.M.B. Intramural Hematoma of the Small Intestine in a Patient with Severe Hemophilia A. Case Report and Review of the Literature. J. Gastrointest. Dig. Syst. 2015, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsumi, A.; Matsushita, T.; Hirashima, K.; Iwasaki, T.; Adachi, T.; Yamamoto, K.; Kojima, T.; Takamatsu, J.; Saito, H.; Naoe, T. Recurrent intramural hematoma of the small intestine in a severe hemophilia A patient with a high titer of factor VIII inhibitor: A case report and review of the literature. Int. J. Hematol. 2006, 84, 166–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janic, D.; Smoljanic, Z.; Krstovski, N.; Dokmanovic, L.; Rodic, P. Ruptured intramural intestinal hematoma in an adolescent patient with severe hemophilia A. Int. J. Hematol. 2009, 89, 201–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carkman, S.; Ozben, V.; Saribeyoğlu, K.; Somuncu, E.; Ergüney, S.; Korman, U.; Pekmezci, S. Spontaneous intramural hematoma of the small intestine. Ulus. Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2010, 16, 165–169. [Google Scholar]

- Sorbello, M.P.; Utiyama, E.M.; Parreira, J.G.; Birolini, D.; Rasslan, S. Spontaneous intramural small bowel hematoma induced by anticoagulant therapy: Review and case report. Clinics 2007, 62, 785–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel Samie, A.; Theilmann, L. Detection and management of spontaneous intramural small bowel hematoma secondary to anticoagulant therapy. Expert. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012, 6, 553–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, E.A.; Han, S.J.; Chun, J.; Lee, H.J.; Chung, H.; Im, J.P.; Kim, S.G.; Kim, J.S.; Yoon, H.; Shin, C.M.; et al. Clinical features and outcomes in spontaneous intramural small bowel hematoma: Cohort study and literature review. Intest. Res. 2019, 17, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiland, M.; Han, S.Y.; Hicks, G.M., Jr. Intramural hemorrhage of the small intestine. JAMA 1978, 239, 139–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iorio, A.; Keepanasseril, A.; Foster, G.; Navarro-Ruan, T.; McEneny-King, A.; Edginton, A.N.; Thabane, L. Development of a Web-Accessible Population Pharmacokinetic Service-Hemophilia (WAPPS-Hemo): Study Protocol. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2016, 5, e239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santagostino, E.; Fasulo, M.R. Hemophilia A and Hemophilia B: Different Types of Diseases? Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2013, 39, 697–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagel, K.; Walker, I.; Decker, K.; Chan, A.K.; Pai, M.K. Comparing bleed frequency and factor concentrate use between haemophilia A and B patients. Haemophilia 2011, 17, 872–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambost, H.; Gaboulaud, V.; Coatmélec, B.; Rafowicz, A.; Schneider, P.; Calvez, T. What factors influence the age at diagnosis of hemophilia? Results of the French hemophilia cohort. J. Pediatr. 2002, 141, 548–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazeef, M.; Sheehan, J.P. New developments in the management of moderate-to-severe hemophilia B. J. Blood Med. 2016, 7, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyvandi, F.; Mannucci, P.M.; Garagiola, I.; El-Beshlawy, A.; Elalfy, M.; Ramanan, V.; Eshghi, P.; Hanagavadi, S.; Varadarajan, R.; Karimi, M.; et al. A Randomized Trial of Factor VIII and Neutralizing Antibodies in Hemophilia A. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 2054–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouw, S.C.; van der Bom, J.G.; Marijke van den Berg, H. Treatment-related risk factors of inhibitor development in previously untreated patients with hemophilia A: The CANAL cohort study. Blood 2007, 109, 4648–4654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudemand, J. Hemophilia. Treatment of patients with inhibitors: Cost issues. Haemophilia 1999, 5, 397–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jewett, T.C., Jr.; Caldarola, V.; Karp, M.P.; Allen, J.E.; Cooney, D.R. Intramural hematoma of the duodenum. Arch. Surg. 1988, 123, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daum, R.; Roth, H.; Bolkenius, M. Problems of intramural haematomas in childhood. A report of 5 cases. Z. Kinderchir. 1982, 36, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, G.S.; Kalapesi, Z.; Temperley, I.J. Intramural duodenal haematoma in a haemophiliac. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 1975, 144, 72–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clement, T.; Göke, M.; Löhr, H.; Kreitner, K.F.; Menke, H.; Bierbach, H.; Ramadori, G. Spontaneous intramural hematoma of the intestinal wall--an unusual hemorrhagic manifestation of hemophilia A. Z. Gastroenterol. 1990, 28, 574–577. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kahn, A.; Vandenbogaert, N.; Cremer, N.; Fondu, P. Intramural hematoma of the alimentary tract in two hemophilic children. Helv. Paediatr. Acta 1977, 31, 503–507. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Weil, B.R.; Howard, T.J.; Zyromski, N.J. Spontaneous duodenal hematoma: A rare cause of upper gastrointestinal tract obstruction. Arch. Surg. 2008, 143, 794–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horan, P.; Drake, M.; Patterson, R.N.; Cuthbert, R.J.; Carey, D.; Johnston, S.D. Acute onset dysphagia associated with an intramural oesophageal haematoma in acquired haemophilia. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2003, 15, 205–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, R.A.; d’Avignon, M.B.; Storch, A.E.; Eyster, M.E. Intramural gastric hematoma in a hemophiliac with an inhibitor. Pediatrics 1981, 67, 417–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, J.M.; Hanly, A.M.; Stephens, R.B. Conservative management resulting in complete resolution of a double intussusception in an adult haemophiliac. Color. Dis. 2008, 10, 197–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarry, J.; Biscay, D.; Lepront, D.; Rullier, A.; Midy, D. Spontaneous intramural haematoma of the sigmoid colon causing acute intestinal obstruction in a haemophiliac: Report of a case. Haemophilia 2008, 14, 383–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliescu, L.E.; Grumeza, M.; Stanciu, A.M.; Toma, L.; Zgura, A.; Cristian, P.G.; Ionescu, C.; Bacinschi, X. Spontaneous Intramural Duodenal Hematoma–A Rare Entity. Surg. Gastroenterol. Oncol. 2022, 27, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, M.; Mantor, C.; O’Connor, J. Duodenal and retroperitoneal hematoma after upper gastrointestinal endoscopy: First presentation of a child with Hemophilia B. J. Pediatr. Surg. Case Rep. 2014, 2, 421–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glassman, M.S.; Rodrigues, R.; Bussel, J.; Spivak, W.; Hilgartner, M. Acute obstructive pancreatitis secondary to a duodenal hematoma. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 1988, 7, 619–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakayama, Y.; Fukushima, M.; Sakai, M.; Hisano, T.; Nagata, N.; Shirahata, A.; Itoh, H. Intramural hematoma of the cecum as the lead point of intussusception in an elderly patient with hemophilia A: Report of a case. Surg. Today 2006, 36, 563–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, J.; Borges, N.; Pascoalinho, J.; Matos, R. Giant Intramural Hematoma of the Colon in Acquired Factor VIII Inhibitor. Acta Med. Port. 2019, 32, 614–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, F.W.; Matthews, J.M. Hemophilic pseudotumor of the stomach. Radiology 1971, 98, 547–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, A.; Blume, M.H.; Insel, J. Spontaneous intramural hematoma of the esophagus. Ann. Intern. Med. 2002, 137, 73–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, Y.K.; Chen, J.H. Adult Jejuno-jejunal intussusception due to inflammatory fibroid polyp: A case report and literature review. Medicine 2020, 99, e22080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, D.S.; Yam, B.; Hines, J.J.; Mazzie, J.P.; Lane, M.J.; Abbas, M.A. Uncommon and unusual gastrointestinal causes of the acute abdomen: Computed tomographic diagnosis. Semin. Ultrasound CT MR 2008, 29, 386–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, H.C.; Lord, R.S.; Chesterman, C.N.; Biggs, J.C.; Tracy, G.D. Spontaneous intramural haematoma in the sigmoid colon of a haemophiliac. Aust. N. Z. J. Surg. 1972, 42, 69–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBlanc, K.E. Jejuno-jejunal intussusception in a hemophiliac: A case report. Ann. Emerg. Med. 1982, 11, 149–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fripp, R.R.; Karabus, C.D. Intussusception in haemophilia: A case report. S. Afr. Med. J. 1977, 52, 617–618. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, B.; Rahman, S.; Osman, A.; Kaushal, N. Giant duodenal hematoma in Hemophilia A. Indian Pediatr. 1996, 33, 411–414. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel Samie, A.; Theilmann, L. Risk factors and management of anticoagulant-induced intramural hematoma of the gastrointestinal tract. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 2013, 39, 191–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manco-Johnson, M.J.; Abshire, T.C.; Shapiro, A.D.; Riske, B.; Hacker, M.R.; Kilcoyne, R.; Ingram, J.D.; Manco-Johnson, M.L.; Funk, S.; Jacobson, L.; et al. Prophylaxis versus episodic treatment to prevent joint disease in boys with severe hemophilia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 535–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, K.; van der Bom, J.G.; Mauser-Bunschoten, E.P.; Roosendaal, G.; Prejs, R.; de Kleijn, P.; Grobbee, D.E.; van den Berg, M. The effects of postponing prophylactic treatment on long-term outcome in patients with severe hemophilia. Blood 2002, 99, 2337–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aledort, L.M.; Haschmeyer, R.H.; Pettersson, H. A longitudinal study of orthopaedic outcomes for severe factor-VIII-deficient haemophiliacs. The Orthopaedic Outcome Study Group. J. Intern. Med. 1994, 236, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ab Rahman, W.S.W.; Zulkafli, Z.; Hassan, M.N.; Abdullah, W.Z.; Husin, A.; Zain, A.A.M. Acute Abdomen: Unmasked the Bleeding Site in Severe Haemophilia A. Malays. J. Med. Health Sci. 2020, 16, 345–347. [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson, A.; Melia, J. A Delayed Diagnosis of Intramural Hematoma in a Hemophiliac: 2050. Off. J. Am. Coll. Gastroenterol.|ACG 2016, 111, S978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, K.H.; Chen, L.M.; Peng, C.M.; Wang, J.D. Spontaneous intramural hemorrhage in a patient with severe hemophilia A. Blood Res. 2014, 49, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zulfikar, O.B.; Emiroglu, H.H.; Yekeler, E.; Kebudi, R. A Rare Clinical Problem: Intestinal Pseudolymphoma in a Patient with Haemophilia A. Int. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2013, 32, 280–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalkling, A.; Pias, S.; Perera, F. Treatment of acute abdomen resulting from hematoma of the jejunum in severe Haemophilia A. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2013, 11, 1059–1060. [Google Scholar]

- Atay, H.; Nural, S.; Kelkitli, E.; Yilmaz, N.; Emer, Z.; Kadi, R.; Güler, N. Intramural hematoma of the small intestine under the prophylaxis. Haematologica 2011, 96, 658. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Cecilia, D.; Torres Tordera, E.M.; Arjona Sánchez, A.; Artero Muñoz, I.; Rufián Peña, S. Spontaneous intramural small bowel hemorrhage: An event on the increase. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2007, 30, 331–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, R.; Iannaccaro, P. Spontaneous intramural intestinal haemorrhage in a haemophiliac patient. Br. J. Haematol. 2004, 125, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, S.H.; Park, Y.S.; Seo, Y.S.; Ha, H.K.; Lee, E.G.; Choi, W.W.; Cho, J.S.; Moon, Y.S.; Choi, I.J.; Cho, S.B. Intramural hematoma of the small intestine in a patient with hemophilia a. Korean J. Gastroenterol. 2003, 41, 145–149. [Google Scholar]

- Hagiwara, T.; Moriya, K.; Nishida, Y.; Satoh, S.; Koyanagi, Y.; Ebihara, Y.; Arai, M.; Fukutake, K. Spontaneous Intramural Hematoma of the Small Intestineina Patient with Hemophilia A—With a review in the literature. Jpn. J. Thromb. Hemost. 2002, 13, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettingshausen, C.E.; Saguer, I.M.; Kreuz, W. Portal vein thrombosis in a patient with severe haemophilia A and F V G1691A mutation during continuous infusion of F VIII after intramural jejunal bleeding--successful thrombolysis under heparin therapy. Eur. J. Pediatr. 1999, 158 (Suppl. S3), S180–S182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onda, M.; Urazumi, K.; Abe, R.; Matsuo, K. Obstructive Ileus caused by blood clot after emergency total gastrectomy in a patient with hemophilia A: Report of a case. Surg. Today 1998, 28, 1266–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamba, G.; Maffé, G.C.; Mosconi, E.; Tibaldi, A.; Di Domenico, G.; Frego, R. Ultrasonographic images of spontaneous intramural hematomas of the intestinal wall in two patients with congenital bleeding tendency. Haematologica 1995, 80, 388–389. [Google Scholar]

- McCoy, H.E., 3rd; Kitchens, C.S. Small bowel hematoma in a hemophiliac as a cause of pseudoappendicitis: Diagnosis by CT imaging. Am. J. Hematol. 1991, 38, 138–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchie, K.; Suzuki, M.; Yamada, M.; Hoshino, S.; Chin, H. Intramural hematoma of the small intestine due to hemophilia A: Report of two cases. Rinsho Hoshasen. 1985, 30, 1599–1602. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, T.G.; Brickman, F.E.; Avecilla, L.S. Ultrasound diagnosis of intramural intestinal hematoma. J. Clin. Ultrasound 1977, 5, 423–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balthazar, E.J.; Einhorn, R. Intramural gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Gastrointest. Radiol. 1976, 1, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, C.D.; Barr, R.D.; Prentice, C.R.; Douglas, A.S. Gastrointestinal bleeding in haemophilia. Q. J. Med. 1973, 42, 503–511. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, I.D.; Chandra, D.; Charan, A.; Sinha, K.N. Haemophilia presenting as acute mechanical small intestinal obstruction. J. Indian. Med. Assoc. 1972, 59, 109–110. [Google Scholar]

- ZhA, K.; Plotnikova, V.A.; Mazchenko, N.S. Intestinal obstruction in a patient with hemophilia. Klin. Med. 1967, 45, 133–134. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchimochi, N.; Nagafuji, K. Spontaneous lesser sac haematoma in a haemophiliac. Br. J. Haematol. 2004, 126, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, S.; Patankar, T.; Krishnan, A.; Pathare, A. Spontaneous isolated lesser sac hematoma in a patient with hemophilia. Indian. J. Gastroenterol. 1999, 18, 38–39. [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto, K.; Hashimoto, T.; Choi, S.; Miyata, Y.; Hara, K.; Kinoshita, S.; Yoshioka, K. Ultrasonographic evaluation of intramural gastric and duodenal hematoma in hemophiliacs. J. Clin. Ultrasound 1988, 16, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisset, R.A.; Gupta, S.C.; Zammit-Maempel, I. Radiographic and ultrasound appearances of an intra-mural haematoma of the pylorus. Clin. Radiol. 1988, 39, 316–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, P.H.; Schnure, F.W.; Chopra, S.; Brooks, D.C.; Gilliam, J.I. Intramural gastrointestinal hemorrhage. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 1986, 8 Pt 2, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshimura, H.; Ohishi, H.; Inoue, K.; Ozaki, M.; Yoshimura, Y.; Iwasaki, H.; Yoshioka, A. Roentgenographic manifestations of intramural hematoma of the stomach in a hemophiliac male (author’s transl). Rinsho Hoshasen. 1978, 23, 1405–1408. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Felson, B. Intramural gastric lesion with sudden abdominal pain. JAMA 1974, 230, 603–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grossman, H.; Berdon, W.E.; Baker, D.H. Reversible gastrointestinal signs of hemorrhage and edema in the pediatric age group. Radiology 1965, 84, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intragumtornchai, T.; Israsena, S.; Benjacholamard, V.; Lerdlum, S.; Benjavongkulchai, S. Esophageal tuberculosis presenting as intramural esophagogastric hematoma in a hemophiliac patient. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 1992, 14, 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldenburger, D.; Gundlach, W.J. Intramural esophageal hematoma in a hemophiliac. An unusual cause of gastrointestinal bleeding. JAMA 1977, 237, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cielecki, C.; Nachulewicz, P.; Rogowski, B.; Obel, M.; Kalińska, A.; Dudkiewicz, E.; Kowalczyk, J. A spontaneous duodenal haematoma with massive bleeding into the abdominal cavity in the course of haemophilia A. A case report. Postępy Nauk. Medycznych 2014, 27, 275–278. [Google Scholar]

- Veltri, A.; Cammarota, T.; Farinet, S.; Serenthà, U. Spontaneous duodenal hematoma in hemophiliac patient, diagnosed with ultrasonography. Radiol. Med. 1992, 83, 316–318. [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto, T.; Yura, J.; Shimizu, Y.; Suzuki, T.; Ishikawa, M.; Mizuno, A. Pyloric ring, Pancreas and Papilla-saving Subtotal Duodenectomy for a Duodenal Submucosal Hematoma in a Patient with Hemophilia. Jpn. J. Gastroenterol. Surg. 1990, 23, 1149–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogués, A.; Eizaguirre, I.; Suñol, M.; Tovar, J.A. Giant spontaneous duodenal hematoma in hemophilia A. J. Pediatr. Surg. 1989, 24, 406–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavrel, M.; Rafowicz, A.; d’Oiron, R.; Franchi-Abella, S.; Lambert, T.; Adamsbaum, C. Imaging features of atypical bleeds in young patients with hemophilia. Diagn. Interv. Imaging 2019, 100, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batista, H.M.T.; de Menezes Silveira, G.B.; Neto, I.C.P.; Pinheiro, W.R.; Bezerra, I.M.P.; Valenti, V.E.; Coelho, D.R.; De Araújo, S.; De Abreu, L.C. Acute abdomen in a patient with haemophilia A: A case study. Int. Arch. Med. 2015, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yankov, I.V.; Spasova, M.I.; Andonov, V.N.; Cholakova, E.N.; Yonkov, A.S. Endoscopic diagnosis of intramural hematoma in the colon sigmoideum in a child with high titer inhibitory hemophilia A. Folia Med. 2014, 56, 126–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nomura, N.; Maruoka, H. A case of intramural rectal hematoma in a patient with hemophilia. Prog. Dig. Endosc. 1999, 54, 122–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pauly, M.P.; Watson-Williams, E.; Trudeau, W.L. Intussusception presenting with lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage in a hemophiliac. Gastrointest. Endosc. 1987, 33, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldberg, M.A.; Hendriks, M.J.; van Waes, P.F. Computed tomography in complicated acute appendicitis. Gastrointest. Radiol. 1985, 10, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, G.S. Intramural colonic haematoma with fistula formation in a haemophiliac. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 1979, 148, 234–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lautkin, A.; Korelitz, B.I.; Berger, L. Roentgen findings in the colon in a hemophiliac with melena. J. Mt. Sinai Hosp. N. Y. 1956, 23, 319–323. [Google Scholar]

| Clinical Variables (Case Number) | Esophagus (n = 3) | Stomach (n = 10) | Duodenum (n = 15) | Small Intestine (n = 34) | Colon (n = 17) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age † Children (31) Adult (45) | 2 0 (0%) 2 (100%) | 10 5 (50%) 5 (50%) | 15 12 (80%) 3 (20%) | 32 6 (18.8%) 26 (81.2%) | 17 8 (47.1%) 9 (52.9%) | 0.0006 *** |

| Nausea/Vomiting † | 3 | 10 | 11 | 33 | 17 | 0.0294 * |

| No (30) Yes (44) | 2 (66.7%) 1 (33.3%) | 2 (20%) 8 (80%) | 3 (27.3%) 8 (72.3%) | 11(33.3%) 22(66.7%) | 12 (70.6%) 5 (29.4%) | |

| Anemia/Pale † No (22) Yes (36) | 2 0 (0%) 2(100%) | 6 1 (16.7%) 5 (83.3%) | 8 1 (12.5%) 7 (87.5%) | 28 16 (57.1%) 12 (42.9%) | 14 4 (28.6%) 10 (71.4%) | 0.0550 * |

| Bleeding into lumen of GI tract † No (46) Yes (27) | 3 1 (33.3%) 2 (66.7%) | 10 9 (90%) 1 (10%) | 11 10 (90.9%) 1 (9.1%) | 33 17 (51.5%) 16 (48.5%) | 16 9 (56.2%) 7 (43.8%) | 0.0281 * |

| Bleeding out of serosa of GI tract † No (47) Yes (26) | 3 2 (66.7%) 1 (33.3%) | 10 7 (70%) 3 (30%) | 11 4 (36.4%) 7 (63.6%) | 33 24 (72.7%) 9 (27.2%) | 16 10 (62.5%) 6 (37.5%) | 0.2901 |

| Intussusception † No (68) Yes (10) | 3 3 (100%) 0 (0%) | 10 10 (100%) 0 (0%) | 15 15 (100%) 0 (0%) | 33 27(81.8%) 6 (18.2%) | 17 13(76.5%) 4 (23.5%) | 0.1783 |

| Management † | 3 | 10 | 15 | 32 | 16 | 0.0221 * |

| Conservative (52) Operation (24) | 2 (66.7%) 1 (33.3%) | 10 (100%) 0 (0%) | 9 (60%) 6 (40%) | 24 (75%) 8 (25%) | 7 (43.8%) 9 (56.3%) | |

| Prognosis † Recovery (65) Mortality (9) | 3 3 (100%) 0 (0%) | 10 10 (100%) 0 (0%) | 15 9 (60%) 6 (40%) | 32 31 (96.9%) 1 (3.1%) | 14 12 (85.7%) 2 (14.3%) | 0.0076 ** |

| Clinical Variables (Case Number) | Children (n = 31) | Adults (n = 49) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trauma † No (38) Yes (10) | 19 10 (52.6%) 9 (47.4%) | 29 28 (96.6%) 1 (3.4%) | 0.0004 *** |

| Anemia/Pale ‡ No (21) Yes (36) | 21 4 (19%) 17 (81%) | 36 17 (47.2%) 19 (52.8%) | 0.0334 * |

| Prognosis † Recovery (62) Mortality (9) | 30 23 (76.7%) 7 (23.3%) | 41 39 (95.1%) 2 (4.9%) | 0.0305 * |

| Clinical Variables (Case Number) | Recovery (n = 68) | Mortality (n = 9) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age † Children (30) Adults (41) | 62 23 (37.1%) 39 (62.9%) | 9 7 (77.8%) 2 (22.2%) | 0.0305 * |

| Location † Esophagus (3) Stomach (10) Duodenum (15) Small intestine (32) Colon (14) | 65 3 (4.6%) 10 (15.4%) 9 (13.8%) 31 (47.7%) 12 (18.5%) | 9 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 6 (66.7%) 1 (11.1%) 2 (22.2%) | 0.0076 ** |

| Inhibitor † No (34) Yes (11) | 43 33 (76.7%) 10 (23.3%) | 2 1 (50%) 1 (50%) | 0.4333 |

| Bleeding into lumen of GI tract † No (44) Yes (25) | 64 41 (64.1%) 23 (35.9%) | 5 3 (60%) 2 (40%) | 1 |

| Bleeding out of serosa of GI tract † No (45) Yes (23) | 64 44 (68.8%) 20 (31.2%) | 4 1 (25%) 3 (75%) | 0.1087 |

| Intussusception † No (64) Yes (10) | 65 55 (84.6%) 10 (15.4%) | 9 9 (100%) 0 (0%) | 0.3466 |

| Management † Conservative (52) Operation (22) | 65 48 (73.8%) 17 (26.2%) | 9 4 (44.4%) 5 (55.6%) | 0.1149 |

| Age/Gender | Public-Ation Year | Coagulation Disorder/Inhibitor Titer (BU/mL) | Site of Hematoma (Etiology/Complications) † | Symptom and Sign | Lab Data ‡ | Treatment | Outcome | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 43/male | 2022 | Severe hemophilia A | Jejunum (impending intussusception) | Generalized abdominal pain, nausea, decreased appetite, tarry stool, rebound tenderness | (1) Hb: 14.9 WBC: 13,170 (2) Hb: 15.0 WBC: 13,690 | factor VIII infusion | Symptom resolution | Our case |

| 2 | 29/male | 2021 | Severe hemophilia A (FVIII: C < 1%)/negative inhibitor | Jejunum (jejuno-jejunal intussusception) | RLQ pain with muscle rigidity, vomiting, and complete ileus, abdominal distension | WBC: 9200 Hb: 14 CRP: 22 | factor VIII infusion | Reduction of intussusception, Regression of hematoma | [1] |

| 3 | 23/male | 2020 | Severe hemophilia A (FVIII: C < 1%)/ negative inhibitor | Small intestine | Generalized abdominal pain, abdominal distension, vomiting, diarrhea, blackish stool, muscle guarding | Hb: 12.2 WBC: 8240 | emergency laparotomy (Small bowel resection with end-to-end anastomosis) | Uneventful recovery | [47] |

| 4 | 37/male | 2016 | Severe hemophilia B (FIX: C < 1%) | Distal small intestine | Abdominal pain, vomiting, abdominal distention | Hb: 13→11 | factor VIIa infusions | Symptoms of obstruction resolved | [48] |

| 5 | 20/male | 2015 | Severe hemophilia A (FVIII: C < 1%) | Jejunum (intestinal subocclusion) | Abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, fever, abdominal distension | WBC: 9810 Hb: 15.9 | factor VIII with von Willebrand factor | Regression of hematoma | [4] |

| 6 | -/- | 2015 | Hemophilia A (FVIII < 0.05) | Jejunum | Abdominal distension, nausea, vomiting, ileus | WBC: 11,100 Hb: 16.6 CRP: 68.6 | factor VIII infusion | Symptoms of ileus resolved | [2] |

| 7 | 49/male | 2014 | Severe hemophilia A (FVIII: C < 1%)/ negative inhibitor | Small intestine (bloody fluid in peritoneal cavity, hemorrhagic infarction) | Bilious vomiting, abdominal pain, peritoneal sign, abdominal distention, no diarrhea, no fever | - | surgical intervention (end-to-end anastomosis) | Complete recovery | [49] |

| 8 | 28/male | 2013 | Severe hemophilia A | Ileum | Abdominal tenderness, occult blood in stool | - | factor VIII infusion | Complete resolution | [50] |

| 9 | 55/male | 2013 | Severe hemophilia A/negative inhibitor | Jejunum | Epigastric pain, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, signs of peritoneal irritation, intestinal bleeding | Hb: 14.6 WBC: 15,000 | factor VIII infusion | Complete resolution | [51] |

| 10 | 25/male | 2011 | Severe hemophilia A | Ileum | Abdominal pain, vomiting, occult blood in stool | Hb: 15.9 WBC: 10,500 | factor VIII infusion | Thickness of the wall had regressed | [52] |

| 11 | 37/male | 2010 | Hemophilia A | Distal ileum | Generalized abdominal tenderness | Hb: 9.7 WBC: 10,700 | conservative therapy | - | [7] |

| 12 | 42/male | 2007 | Hemophilia A | Small intestine | Abdominal pain | - | conservative therapy | Complete resolution | [53] |

| 13 | 17/male | 2006 | Severe hemophilia A (FVIII: C < 1%)/high inhibitor (1024 BU/mL) | Jejunum | Total 5 episodes: (1~3) abdominal pain, vomiting (4) abdominal pain, melena, muscular defense (5) abdominal pain, melena | (1) Hb: 14.8 WBC: 9900 (2) Hb:16.8 WBC:12,200 CRP: 8.2 | (1~4) APCC (5) rFVIIa → APCC | Symptom resolution | [5] |

| 14 | 34/male | 2005 | Severe hemophilia A/high inhibitor | Jejunum (acute intestinal obstruction) | Abdominal pain, no passed for 2 d, vomit green bile, abdominal distension | Hb: 16.4 WBC: 18,000 | rFVIIa | Symptom resolution | [3] |

| 15 | 74/male | 2004 | Mild hemophilia A/inhibitor (27 BU/mL) | Jejunum | Hematemesis, severe anemia, signs of bowel obstruction | Hb: 7 | aPCC followed by rFVIIa | - | [54] |

| 16 | 54/male | 2003 | Moderate hemophilia A (FVIII: C 3%) | Small intestine | Abdominal pain, diarrhea, pale conjunctiva, hyperactive bowel sound | Hb: 10.0 WBC: 4700 | factor VIII infusion | Symptom resolution | [55] |

| 17 | 38/- | 2002 | Moderate hemophilia A (FVIII: C 2.7%) | Small intestine | Abdominal pain, vomiting, peritoneal sign, hypoactive bowel sound | Hb: 13.6 WBC: 3500 | emergency laparotomy (resected involved bowel and end-to-end anastomosis) | Uneventful recovery | [56] |

| 18 | 14/male | 1999 | Severe hemophilia A | Jejunum (trauma-related) | Traumatic intramural hematoma | - | factor VIII infusion | Resorption of the hematoma | [57] |

| 19 | 54/male | 1998 | Mild hemophilia A (FVIII: C 16%) | Jejunum (on the anal side of the Y anastomosis after Roux-en-Y gastrectomy) | Coffee-ground emesis, diffuse abdominal tenderness, decreased bowel sound | Hb: 7.1 | second laparotomy (remove intramural blood clot) | Obstructive ileus improved | [58] |

| 20 | 47/male | 1995 | Severe hemophilia A (FVIII < 1 U/dL)/low titer of inhibitor (0.9 BU/mL) | Terminal ileum | Abdominal pain, subocclusive state mimic appendicitis, blood present in stool | Hb: 14.3 | factor VIII infusion | Complete resolution | [59] |

| 21 | 68/male | 1991 | Severe hemophilia A/no inhibitor | Terminal ileum | RLQ abdominal pain, abdominal distention, diarrhea, peritoneal sign, hypoactive bowel sound | Hct: 39% WBC: 4400 | factor VIII infusion | Complete resolution of hematoma | [60] |

| 22 | 49/male | 1990 | Severe hemophilia A (FVIII: C < 1%) | Small intestine | Generalized abdominal pain, abdominal distention, nausea, no vomiting, decreased appetite | Hb: 9.7 | factor VIII infusion | Symptoms subsided | [23] |

| 23 | 31/male | 1985 | Hemophilia A | Jejunum (500 mL hemoperitoneum) | Angina, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting | Hb: 16.6 WBC: 17,600 | laparotomy (small bowel resection) | - | [61] |

| 24 | 40/male | 1985 | Hemophilia A | Small intestine | Abdominal pain, vomiting | Hb: 14.1 WBC: 18,600 | factor VIII infusion | Symptom resolution | [61] |

| 25 | 8/male | 1982 | Hemophilia A | Jejunum (trauma-related/ jejuno-jejunal intussusception with mild edematous pancreatitis) | Abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, epigastric palpable mass, bilateral flank dullness, rebound tenderness, hemodynamic instability | Hb: 8.3 WBC: 19,000 Amylase: 75→725 (56~190) | exploratory laparotomy (jejunal hematoma evacuation, intussusception reduced) | Follow up normal | [42] |

| 26 | 34/male | 1978 | Hemophilia A/anti-factor VIII antibodies | Small intestine | Epigastric pain, abdominal distension, melena, hematemesis, anemia | Hct: 47→17% | clotting factor, vasopressin infusion | Significant hematemesis and died | [11] |

| 27 | 19/male | 1978 | Hemophilia A | Small intestine (transient intussusception) | Diffuse abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, melena, no bowel movement, slightly bloody vomitus, anemia | Hct: 40→23% | clotting factor | Symptom resolution | [11] |

| 28 | 16/male | 1978 | Hemophilia B | Distal jejunum (intermittent intussusception) | Postprandial vomiting, periumbilical pain, no bowel movement | - | clotting factor | Symptom resolution | [11] |

| 29 | 47/male | 1978 | Hemophilia | jejunum | RUQ pain with decreased bowel sound, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, bloody stool | Hct: 28→23% | clotting factor | Symptom resolution | [11] |

| 30 | 59/male | 1977 | Hemophilia A/ anti-factor VIII antibody | Small intestine | Abdominal pain, intra-abdominal irritation, occult blood | Hct: 42.6% | - | - | [62] |

| 31 | 31/male | 1976 | Hemophilia | Small intestine | Abdominal pain, melena | - | - | - | [63] |

| 32 | -/- | 1973 | Hemophilia | ileum | volvulus, intestinal obstruction symptoms | - | surgical resection of ileum | Symptom-free for 2 years | [64] |

| 33 | 16/male | 1972 | Hemophilia A | Small intestine | Generalized abdominal pain, absolute constipation, abdominal distension, recurrent vomiting, dehydration, anemia, hematemesis, melena | Hb: 9 WBC: 8000 | fresh blood and conservative therapy | Condition improved | [65] |

| 34 | 12/male | 1967 | Hemophilia | Ileum (trauma-related) | Abdominal cramping pain, vomiting, generalized weakness, pale, peritoneal sign | Hb: 6 WBC: 25,900 | laparotomy (resection of the intestine with end-to-end anastomosis) | Condition improved | [66] |

| Age/Gender | Public-Ation Year | Coagulation Disorder/Inhibitor Titer (BU/mL) | Site of Hematoma (Etiology/Complications) † | Symptom and Sign | Lab Data ‡ | Treatment | Outcome | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 24/male | 2004 | Hemophilia A | Stomach lesser sac | Cramping abdominal pain, nausea | WBC: 11,500 CRP: 4.6 | factor VIII infusion | Symptoms subsided | [67] |

| 2 | 10/male | 1999 | Severe hemophilia A (FVIII: C < 1%) | Stomach lesser sac | Non-colicky hypochondrial pain | - | factor VIII infusion | Symptoms subsided | [68] |

| 3 | 20/male | 1988 | Hemophilia A | Posterior wall of the stomach and in the lesser sac | Severe abdominal pain, abdominal distension, nausea, vomiting | - | factor VIII infusion | Symptoms subsided | [69] |

| 4 | 5.5 month/male | 1988 | Moderate hemophilia A (FVIII: C: 1%) | Pylorus (iatrogenic/gastric outlet obstruction) | Signs of gastric outlet obstruction | Hb: 7.3 | cryoprecipitate | Widened pyloric lumen | [70] |

| 5 | 23/male | 1986 | Mild hemophilia A (FVIII: C: 10%) | Stomach | Low-grade fever, cramping abdominal pain, nausea, diarrhea, muscle guarding | Hct: 43→29% WBC: 4200 | cryoprecipitate | Resolution of the hematoma | [71] |

| 6 | 9y11m/male | 1981 | Hemophilia A (factor VIII <0.1 unit/mL)/low titer inhibitor (4~8 BU/mL) | Stomach (partial gastric outlet obstruction) | Cramping intermittent LUQ pain, nausea, early satiety, vomiting with postprandial regurgitation, LUQ firm and tender mass, anemia | Hb: 7.6 Hct: 22% WBC: 11,600 | antihemophilic factor (AHF) concentrate | Symptoms subsided | [27] |

| 7 | 23/male | 1978 | Severe hemophilia A | Stomach | Epigastric pain with LUQ muscle guarding, vomiting, anemia, no bloody stool, no hematuria | Leukocytosis with left shift, Elevated CRP | factor VIII infusion | Symptoms subsided | [72] |

| 8 | 22/male | 1974 | Hemophilia A | Stomach | Epigastric pain, nausea, vomiting | - | cryoprecipitate anti-hemophilic globulin | Symptoms subsided | [73] |

| 9 | 8/male | 1971 | Hemophilia A | Stomach | Nausea, vomiting with bile-stained vomitus, left hypochondrial mass | - | antihemophilic globulin | Mass regression | [35] |

| 10 | 8.5/male | 1965 | Hemophilia | Stomach (significant bleeding into retrogastric space) | Anemia | Hb: 9→6.9 | fresh frozen plasma | Resolution of the hematoma | [74] |

| Age/Gender | Public-Ation Year | Coagulation Disorder/Inhibitor Titer (BU/mL) | Site of Hematoma (Etiology/Complications) † | Symptom and Sign | Lab Data ‡ | Treatment | Outcome | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | n.s/male | 2002 | Hemophilia A | Esophagus | Acute odynophagia, substernal chest pain radiating to the anterior chest and shoulder | - | factor VIII infusion | Resolution of symptoms and hematoma | [36] |

| 2 | 31/male | 1992 | Moderate hemophilia A (basal factor VIII level: 4.5%)/without inhibitor | Esophagus from incisor to carina (hematoma intraluminally ruptured) | Retrosternal pain radiate to back, dysphagia, acute distress and febrile, bloody stool, significant hematemesis | Hb: 7.3 WBC: 14,600 | cryoprecipitate with surgical intervention (gastrostomy, esophagostomy) | Resolution of symptoms and hematoma | [75] |

| 3 | 38/male | 1977 | Hemophilia A | Esophagus | Nausea, hematemesis | Hct: 40→32% | antihemophilic factor | Complete resolution of lesion | [76] |

| Age/Gender | Public-Ation Year | Coagulation Disorder/Inhibitor Titer (BU/mL) | Site of Hematoma (Etiology/Complications) † | Symptom and Sign | Lab Data ‡ | Treatment | Outcome | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 52/male | 2022 | Hemophilia A | Duodenum with acute edematous pancreatitis | Epigastric abdominal pain, vomiting, absence of intestinal transit | Hb: 8.5 WBC: 17,700 CRP: 66.3 (0~3) elevated lipase and amylase | factor VIII infusion | Recovery of pancreatitis and hematoma | [30] |

| 2 | 7/male | 2014 | Moderate to severe hemophilia B (FIX level: 2%) | Duodenum (intra-peritoneal hemorrhage) | Hemodynamic instability, abdominal pain, abdominal distention, changed mental status, vomiting, anorexia | Severe anemia | exploratory laparotomy (drainage of hematoma) | Uneventful recovery | [31] |

| 3 | 14/male | 2014 | Mild hemophilia A | Duodenum (significant hemoperitoneum) | Abdominal pain, abdominal distension, hypovolemic shock, peritoneal sign | Hct: 27.4% | emergency laparotomy (evacuation of hematoma) | Uneventful recovery | [77] |

| 4 | 10/male | 1996 | Hemophilia A | Duodenum (caused gastric outlet obstruction) | Abdominal pain, non-bilious vomiting, constipation, muscle guarding, decrease bowel sound | normal blood counts | factor VIII infusion | Symptoms resolved | [42] |

| 5 | 47/male | 1992 | Hemophilia | Duodenum | Epigastric pain, right hypochondrium pain, N/V, muscle defense | - | coagulation factor infusion | Symptoms resolved | [78] |

| 6 | 15/male | 1990 | Mild hemophilia A (FVIII:13.2%) | Duodenum (trauma-related/retroperitoneal bleeding and acute pancreatitis) | Epigastric pain, hypotension with hypovolemic shock, muscle guarding, abdominal distention | Hb: 12.8→8.1 WBC: 27,400 Amylase: 8530 | emergency laparotomy (subtotal duodenectomy preserving the pylorus and papillae) | Large amount of bleeding from the drain on 6th post-operation day, improved after factor VIII infusion | [79] |

| 7 | 12/male | 1989 | Hemophilia A | Duodenum (retroperitoneal bleeding) | Right side abdominal pain, vomiting, pallor, weakness, right iliac tenderness with rebound pain, cholestatic jaundice | Hct: 27% elevated amylase | factor VIII infusion (abdomen was entered initially without definite diagnosis) | Hematoma decreased rapidly and bleeding episode stabilized under conservative treatment | [80] |

| 8 | child | 1988 | Hemophilia | Duodenum | - | - | deferred surgery (>24 h) | Died | [20] |

| 9 | child | 1988 | Hemophilia | Duodenum | - | - | deferred surgery (>24 h) | Died | [20] |

| 10 | child | 1988 | Hemophilia | Duodenum | - | - | conservative therapy | Died | [20] |

| 11 | child | 1988 | Hemophilia | Duodenum | - | - | conservative therapy | Died | [20] |

| 12 | 16/male | 1988 | Hemophilia A with inhibitor | Duodenum | Abdominal pain, vomiting | - | aPCC | Resolution of symptoms | [69] |

| 13 | 18/male | 1988 | Hemophilia A | Duodenum (acute obstructive pancreatitis) | Acute periumbilical pain, bilious vomiting, diminished bowel sound, palpable mass at RUQ | Hct: 42.9% Amylase: 3000 | factor VIII infusion | Resolution of symptoms | [32] |

| 14 | 11/male | 1977 | Hemophilia | Duodenum (rapidly developing hemomediastinum) | Severe abdominal pain | - | surgical intervention | Died | [24] |

| 15 | 2/male | 1975 | Severe hemophilia A | Duodenum (trauma-related/obstruction of the opening of ampulla Vater causing dilatation of CBD, significant hemoperitoneum) | Significant hematemesis, dark red vomitus, febrile, drowsy, pale, generalized hypotonia, hypotension, pulsatile and palpable mass in the epigastrium | Hb: 7.6 | cryoprecipitate | Died (sudden deterioration) | [22] |

| Age/Gender | Public-Ation Year | Coagulation Disorder/Inhibitor Titer (BU/mL) | Site of Hematoma (Comorbidities/Complications) † | Symptom and Sign | Lab Data ‡ | Treatment | Outcome | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10/male | 2019 | Severe hemophilia A | Rectum | Abdominal pain, pelvic tenderness, long-lasting constipation | Hb: 6 | - | - | [81] |

| 2 | 15/male | 2015 | hemophilia A | Cecum (mimic acute appendicitis) | Abdominal pain in the right iliac fossa, vomiting, anorexia, abdominal guarding | Hb: 9.4 WBC: 16,000 | exploratory laparotomy (appendectomy and drainage) | Uneventful recovery | [82] |

| 3 | 7/male | 2014 | Mild hemophilia A /high titer inhibitor(>10 BU/mL) | Sigmoid colon (traumatic Hx) | Rectorrhagia, colicky pain in the suprapubic region | no anemia | rFVII a, aPCC | Resolution of hematoma | [83] |

| 4 | 17/male | 2009 | Severe hemophilia A without inhibitors | Sigmoid colon (severe cough Hx/ruptured into peritoneal space causing hemoperitoneum and right hematocele) | Swelling of the lower abdomen and right scrotum, abdominal distention with large tender palpable mass in the infraumbilical region, Hb drop | Hb: 11.7→8.7 WBC: 17,800 CRP: 79 (<3) | factor VIII infusion | Regression of hemoperitoneum | [6] |

| 5 | 55/male | 2008 | Hemophilia A | Sigmoid colon (complete intestinal obstruction) | Right side abdominal pain, abdominal distention, acute compartmental syndrome (renal dysfunction and respiratory distress) | WBC: 22,900 Hb: 9.5 Hct: 27.5% | emergency laparotomy (Hartman procedure) | Uneventful recovery | [29] |

| 6 | 29/male | 2007 | Severe hemophilia A | 1st: Caecum and ascending colon 2nd: Transverse colon (two associated colo-colic intussusceptions) | Right iliac fossa pain, vomiting, large tender and locally guarded mass in the RLQ, rectorrhagia | Hb: 15.1 WBC: 16,400 | factor VIII infusion | Reduction in size of the hematoma and complete resolution of the intussusceptions | [28] |

| 7 | 65/male | 2006 | Hemophilia A/inhibitor: 1 BU/mL | Cecum (ileus → [16 days later] → colo-colic intussusception) | Abdominal distension, right- side abdominal pain → [16 days later] → bloody stool, palpable mass in the RLQ, no rebound tenderness | Hb: 10.1 Hct: 32.9% WBC: 9100 | conservative therapy → [16 days later] → laparotomy (surgical reduction fail, followed by right colectomy) | Uneventful recovery | [33] |

| 8 | 26/male | 1999 | Severe hemophilia A (FVIII: C < 1%) | Rectum | Lower abdominal pain, constipation | - | cryoprecipitate | Symptoms resolved | [84] |

| 9 | 38/male | 1990 | Moderate hemophilia A (FVIII activity: 2%) | Ascending colon | Abdominal pain with muscle defense, palpable firm mass, no vomiting, no per-anal bleeding | No anemia WBC: 12,100 | laparotomy (right hemicolectomy) (because factor VIII infusion failed) | Died of sepsis with multi-organ failure | [23] |

| 10 | 25/male | 1987 | Hemophilia A with inhibitor | Cecum (ceco-colic intussusception) | Right side severe abdominal pain, abdominal distention, hematochezia, nausea, vomiting, decreased bowel sound | Hct: 20% WBC: 10,000 | laparotomy (right hemicolectomy) | Uneventful recovery | [85] |

| 11 | 23/male | 1985 | Hemophilia B | Cecum (appendix rupture, intraperitoneal abscess) | Abdominal complaints, vomitus, loss of appetite | - | surgery | - | [86] |

| 12 | 12/male | 1982 | Hemophilia A | Sigmoid colon to rectum | Diffuse abdominal tenderness, pale, peritoneal sign | Hb: 9.6 | laparotomy | Died (severe underlying disease) | [21] |

| 13 | 49/male | 1979 | Hemophilia A | Ascending colon (fistula formed between colon and iliacus muscle) | Appendicitis-like symptoms | - | operation (bypass cecum and ascending colon, with ileum and transverse colon anastomosis) | - | [87] |

| 14 | 13.5/male | 1977 | Severe hemophilia A (FVIII activity: <1%) | Colon (ileocolic intussusception) | RUQ abdominal pain, vomiting, palpable mass in the RUQ | - | barium enema reduction, cryoprecipitate | Symptoms improved | [41] |

| 15 | 9/male | 1977 | Hemophilia A | Descending colon | Abdominal pain, melena, severe anemia | Severe anemia | cryoprecipitate | Uneventful recovery | [24] |

| 16 | 36/male | 1972 | Mild hemophilia A (FVIII concentration 8~19%) | Sigmoid colon (rupture into peritoneal space) | Constipation, abdominal distension, tenderness (maximal in the left iliac fossa), small passage of blood per rectum | Hypovolemia | laparotomy (resected involved sigmoid colon) | Postoperative intraperitoneal hemorrhage episodes resolved under cryoprecipitate | [39] |

| 17 | 12/male | 1956 | Hemophilia A | Distal transverse colon | Bloody stool, hypotension, pale | Hb: 6.8 Hct: 21% WBC: 6800 | fresh frozen plasma | Resolution of hematoma | [88] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Teng, W.-J.; Kung, C.-H.; Cheng, M.-M.; Tsai, J.-R.; Chang, C.-Y. Intramural Hematoma of Gastrointestinal Tract in People with Hemophilia A and B. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3093. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12093093

Teng W-J, Kung C-H, Cheng M-M, Tsai J-R, Chang C-Y. Intramural Hematoma of Gastrointestinal Tract in People with Hemophilia A and B. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(9):3093. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12093093

Chicago/Turabian StyleTeng, Wei-Jung, Ching-Huei Kung, Mei-Mei Cheng, Jia-Ruey Tsai, and Chia-Yau Chang. 2023. "Intramural Hematoma of Gastrointestinal Tract in People with Hemophilia A and B" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 9: 3093. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12093093