Anesthesia Analysis of Compound Lidocaine Cream Alone in Adult Male Device-Assisted Circumcision

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Patients

2.2. Surgical Process

2.3. Follow-Up

- Are you satisfied with the anesthetic effect of lidocaine combined cream? Please tell us your satisfaction in the form of a score after considering the anesthesia cost, anesthesia method and anesthesia effect. A score of 0 represents very dissatisfied and a score of 10 represents very satisfied. The higher the value, the more satisfied the patient.

- Are you willing to use lidocaine combined cream as your first choice of anesthesia if you are undergoing circumcision again?

- What do you think is the greatest advantage of combined lidocaine cream for anesthesia during circumcision?

- What do you think needs to be improved in the anesthesia of combined lidocaine cream for circumcision?

3. Results:

3.1. Anesthetic Expenses

3.2. Time and Pain of Anesthesia

3.2.1. Anesthesia Time Cost

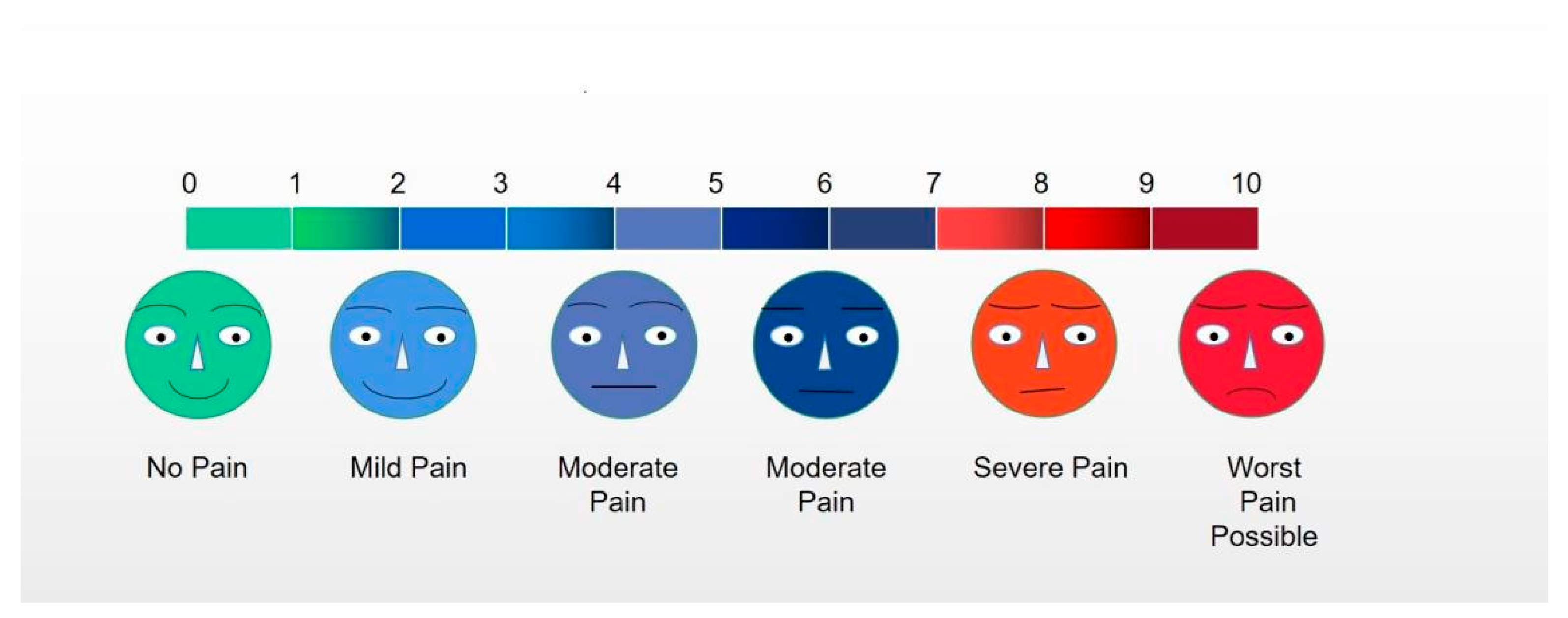

3.2.2. Anesthesia Pain Degree

3.3. Duration of Anesthesia

3.3.1. Initial Time of Pain Detection

3.3.2. Age Distribution Characteristics

3.4. Anesthetic Effect

3.5. Anesthetic Side Effect

3.6. Anesthesia Satisfaction

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dunsmuir, W.D.; Gordon, E.M. The history of circumcision. BJU Int. 1999, 83 (Suppl. 1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krieger, J.N.; Bailey, R.C.; Opeya, J.; Ayieko, B.; Opiyo, F.; Agot, K.; Parker, C.; Ndinya-Achola, J.O.; Magoha, G.A.; Moses, S. Adult male circumcision: Results of a standardized procedure in Kisumu District, Kenya. BJU Int. 2005, 96, 1109–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massry, S.G. History of circumcision: A religious obligation or a medical necessity. J. Nephrol. 2011, 24 (Suppl. 17), S100–S102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Liu, X.; Wei, G.-H. Foreskin development in 10 421 Chinese boys aged 0–18 years. World J. Pediatr. 2009, 5, 312–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, R.C.; Moses, S.; Parker, C.B.; Agot, K.; Maclean, I.; Krieger, J.N.; Williams, C.F.; Campbell, R.T.; Ndinya-Achola, J.O. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in young men in Kisumu, Kenya: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2007, 369, 643–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auvert, B.; Taljaard, D.; Lagarde, E.; Sobngwi-Tambekou, J.; Sitta, R.; Puren, A. Randomized, controlled intervention trial of male circumcision for reduction of HIV infection risk: The ANRS 1265 Trial. PLoS Med. 2005, 2, e298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, R.H.; Kigozi, G.; Serwadda, D.; Makumbi, F.; Watya, S.; Nalugoda, F.; Kiwanuka, N.; Moulton, L.H.; Chaudhary, M.A.; Chen, M.Z.; et al. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in men in Rakai, Uganda: A randomised trial. Lancet 2007, 369, 657–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westercamp, N.; Bailey, R.C. Acceptability of Male Circumcision for Prevention of HIV/AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Review. AIDS Behav. 2006, 11, 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattson, C.L.; Bailey, R.C.; Muga, R.; Poulussen, R.; Onyango, T. Acceptability of male circumcision and predictors of circumcision preference among men and women in Nyanza Province, Kenya. AIDS Care 2005, 17, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngalande, R.C.; Levy, J.; Kapondo, C.P.N.; Bailey, R.C. Acceptability of Male Circumcision for Prevention of HIV Infection in Malawi. AIDS Behav. 2006, 10, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sara, C.A.; Lowry, C.J. A Complication of Circumcision and Dorsal Nerve Block of the Penis. Anaesth. Intensive Care 1985, 13, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laffon, M.; Gouchet, A.; Quenum, M.; Haillot, O.; Mercier, C.; Huguet, M. Eutectic mixture of local anesthetics in adult urology patients: An observational trial. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 1998, 23, 502–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taddio, A.; Stevens, B.; Craig, K.; Rastogi, P.; Ben-David, S.; Shennan, A.; Mulligan, P.; Koren, G. Efficacy and Safety of Lidocaine–Prilocaine Cream for Pain during Circumcision. N. Engl. J. Med. 1997, 336, 1197–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benini, F.; Johnston, C.C.; Faucher, D.; Aranda, J.V. Topical anesthesia during circumcision in newborn infants. JAMA 1993, 270, 850–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bijur, P.E.; Silver, W.; Gallagher, E.J. Reliability of the Visual Analog Scale for Measurement of Acute Pain. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2001, 8, 1153–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, Z.-D.; Lv, B.-D.; Zhang, S.-G.; Zhu, X.-W.; Chen, G.; Chen, M.-F.; Shen, H.-L.; Pei, Z.-J. Disposable circumcision suture device: Clinical effect and patient satisfaction. Asian J. Androl. 2014, 16, 453–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serour, F.; Mori, J.; Barr, J. Optimal Regional Anesthesia for Circumcision. Anesth. Analg. 1994, 79, 129–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozen, V.; Yigit, D. A comparison of the postoperative analgesic effectiveness of low dose caudal epidural block and US-guided dorsal penile nerve block with in-plane technique in circumcision. J. Pediatr. Urol. 2020, 16, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gyftopoulos, K.I. The efficacy and safety of topical EMLA cream application for minor surgery of the adult penis. Urol. Ann. 2012, 4, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mujeeb, S.; Akhtar, J.; Ahmed, S. Comparison of eutectic mixture of local anesthetics cream with dorsal penile nerve block using lignocaine for circumcision in infants. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2013, 29, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| VAS Pain Score | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phimosis (percent, %) | 289 (44.53) | 207 (31.89) | 88 (13.56) | 21 (3.24) | 4 (0.62) | 2 (0.31) | 3 (0.46) | 1 (0.15) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 615 (94.76) |

| Severe Phimosis (percent, %) | 0 | 5 (0.77) | 8 (1.23) | 10 (1.54) | 5 (0.77) | 2 (0.31) | 2 (0.31) | 2 (0.31) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 34 (5.24) |

| The Initial Time of Pain Detection | No Change | 1 h after Surgery | 2 h after Surgery | 3 h after Surgery | 4 h after Surgery | 5 h after Surgery | 6 h after Surgery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 14 | 135 | 357 | 81 | 37 | 16 | 9 |

| Percentage (%) | 2.1 | 20.8 | 55 | 12.5 | 5.7 | 2.5 | 1.4 |

| The Initial Time of Pain Detection | No Change | 1 h after Surgery | 2 h after Surgery | 3 h after Surgery | 4 h after Surgery | 5 h after Surgery | 6 h after Surgery | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number aged 18–44 years | 10 | 129 | 343 | 78 | 35 | 15 | 8 | 618 |

| Percentage (%) | 1.6 | 20.8 | 55.5 | 12.6 | 5.6 | 2.6 | 1.3 | 100 |

| Number aged 45–59 years | 3 | 6 | 13 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 27 |

| Percentage (%) | 11.1 | 22.2 | 48.2 | 7.4 | 7.4 | 0 | 3.7 | 100 |

| Number aged 60–74 years | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| Percentage (%) | 25 | 0 | 25 | 0 | 25 | 25 | 0 | 100 |

| VAS Pain Score | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phimosis (%) | 252 (38.83) | 213 (32.82) | 135 (20.80) | 8 (1.23) | 5 (0.77) | 1 (0.15) | 1 (0.15) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 615 (94.76) |

| Severe Phimosis (%) | 4 (0.62) | 8 (1.23) | 14 (2.16) | 6 (0.92) | 1 (0.15) | 1 (0.15) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 34 (5.24) |

| Side Effects | Headache and Dizziness | Nausea and Vomiting | Blood Pressure Decline or Heart Rate Drops | Chills | Transient Erythema |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 431 |

| Percentage (%) | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 66.4 |

| Questions Asked | Evaluation and Description | Number | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Question 1 (Satisfaction Scores) | 0–3 | 0 | 0 |

| 4–7 | 19 | 2.9 | |

| 8–10 | 630 | 97.1 | |

| Question 2 (Attitudes) | Very willing | 603 | 92.9 |

| Somewhat willing | 41 | 6.3 | |

| Not willing | 5 | 0.8 | |

| Question 3 (Advantages) | Comfortable | 141 | 21.7 |

| No needle | 386 | 59.5 | |

| Safe | 96 | 14.8 | |

| Else | 26 | 4.0 | |

| Question 4 (Shortcomings) | Mild pain | 272 | 42.0 |

| Transient itching | 189 | 29.1 | |

| Price | 107 | 16.5 | |

| Else | 81 | 12.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zheng, Z.; Ding, K.; Tang, Z.; Wu, Z.; Li, Z.; Wang, G.; Fan, B.; Wang, Z. Anesthesia Analysis of Compound Lidocaine Cream Alone in Adult Male Device-Assisted Circumcision. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3121. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12093121

Zheng Z, Ding K, Tang Z, Wu Z, Li Z, Wang G, Fan B, Wang Z. Anesthesia Analysis of Compound Lidocaine Cream Alone in Adult Male Device-Assisted Circumcision. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(9):3121. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12093121

Chicago/Turabian StyleZheng, Zhihuan, Ke Ding, Zhengyan Tang, Ziqiang Wu, Zhongyi Li, Guilin Wang, Benyi Fan, and Zhao Wang. 2023. "Anesthesia Analysis of Compound Lidocaine Cream Alone in Adult Male Device-Assisted Circumcision" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 9: 3121. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12093121

APA StyleZheng, Z., Ding, K., Tang, Z., Wu, Z., Li, Z., Wang, G., Fan, B., & Wang, Z. (2023). Anesthesia Analysis of Compound Lidocaine Cream Alone in Adult Male Device-Assisted Circumcision. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(9), 3121. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12093121