Status of Body Contouring Following Metabolic Bariatric Surgery in a Tertiary Hospital of Greece—Still a Long Way to Go

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Statistical Analysis

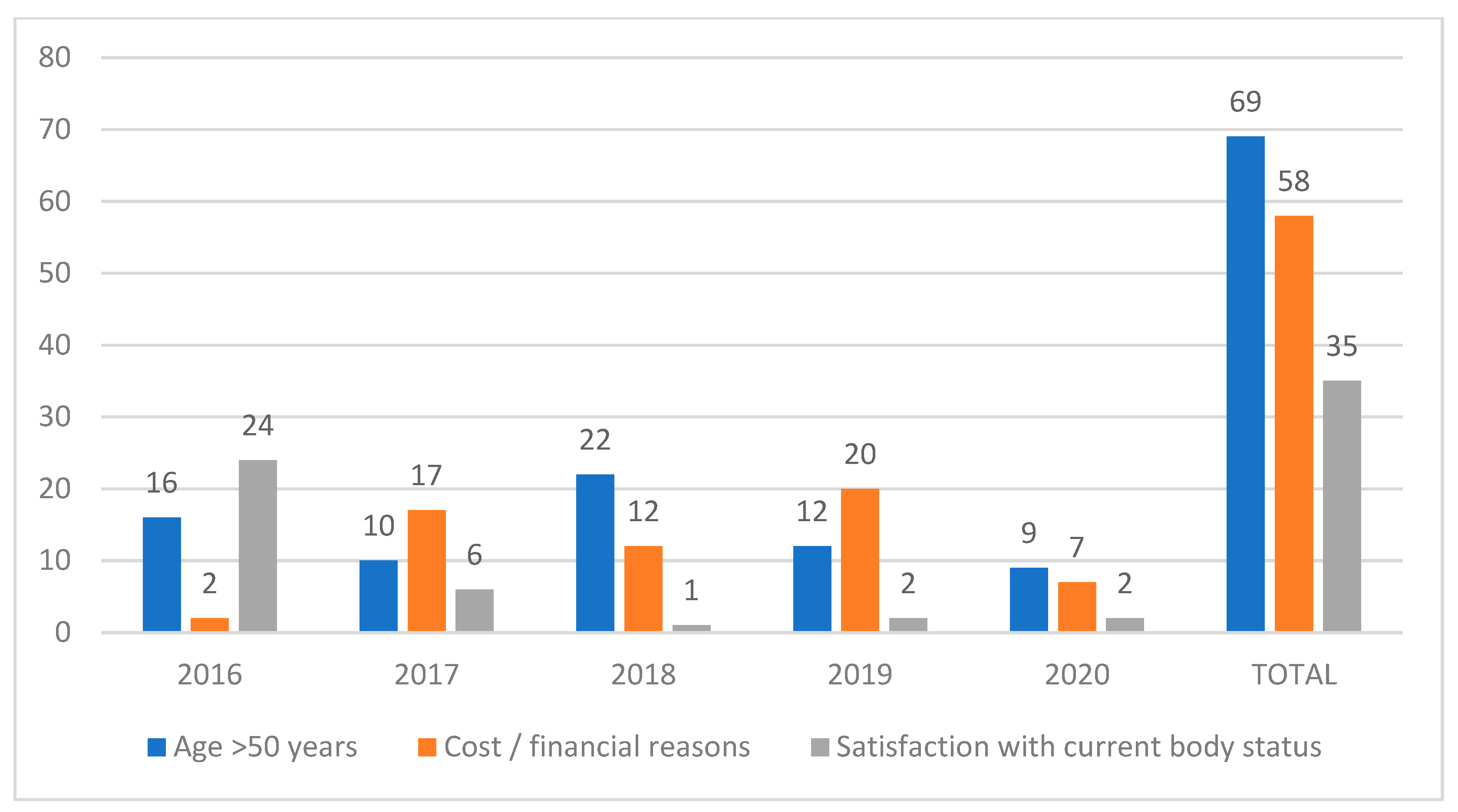

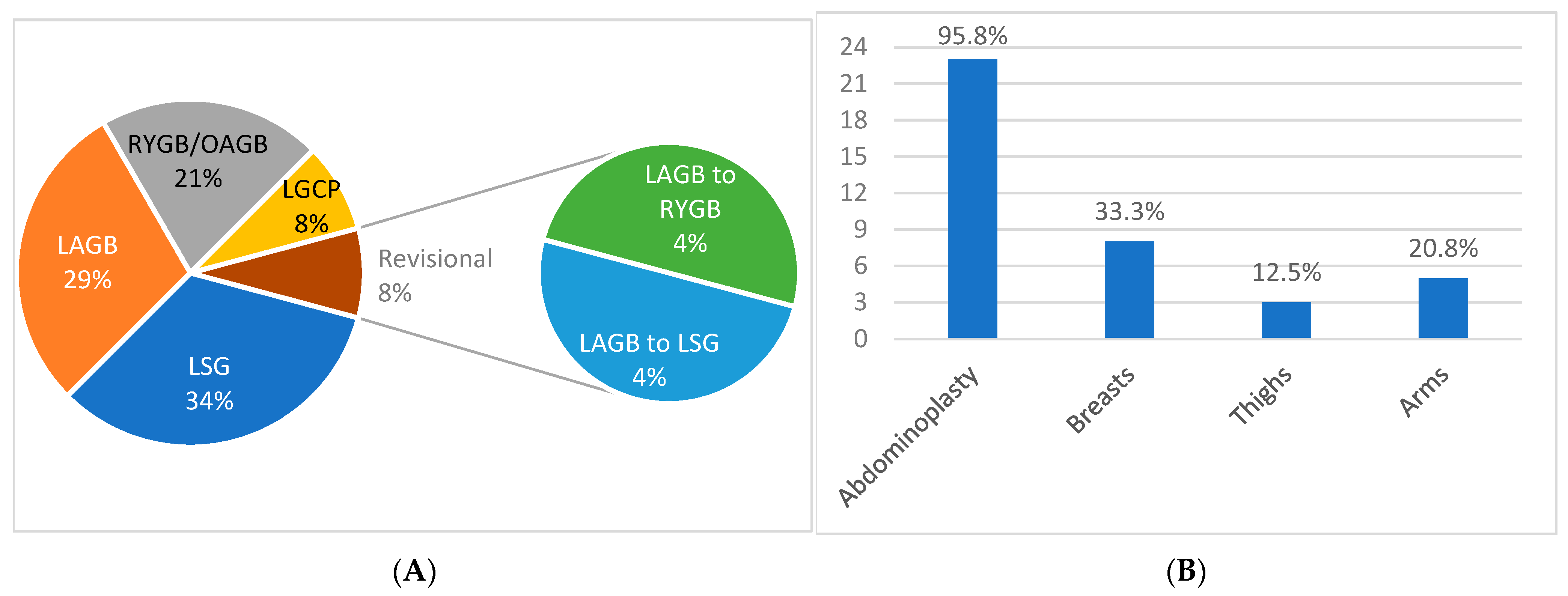

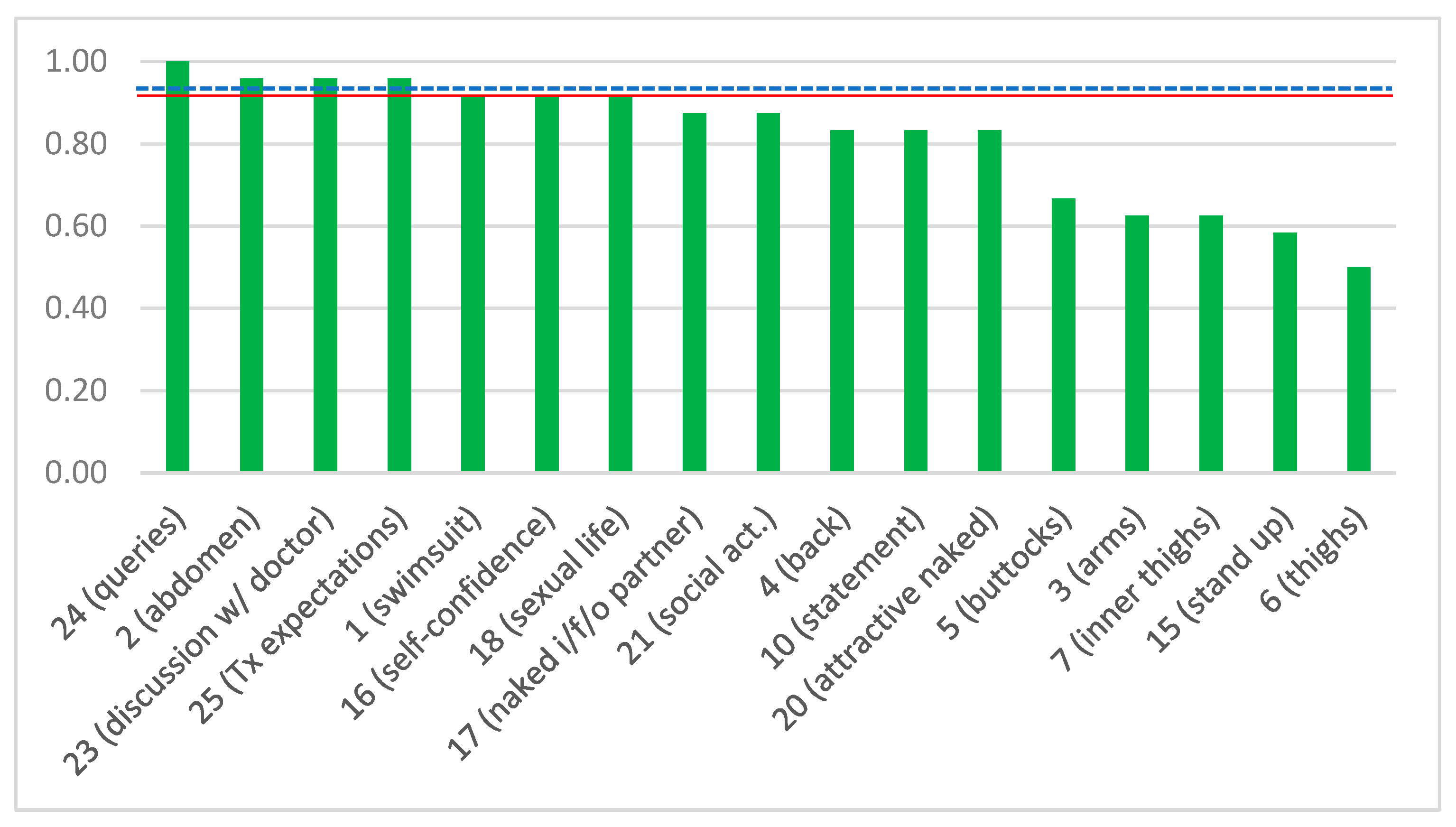

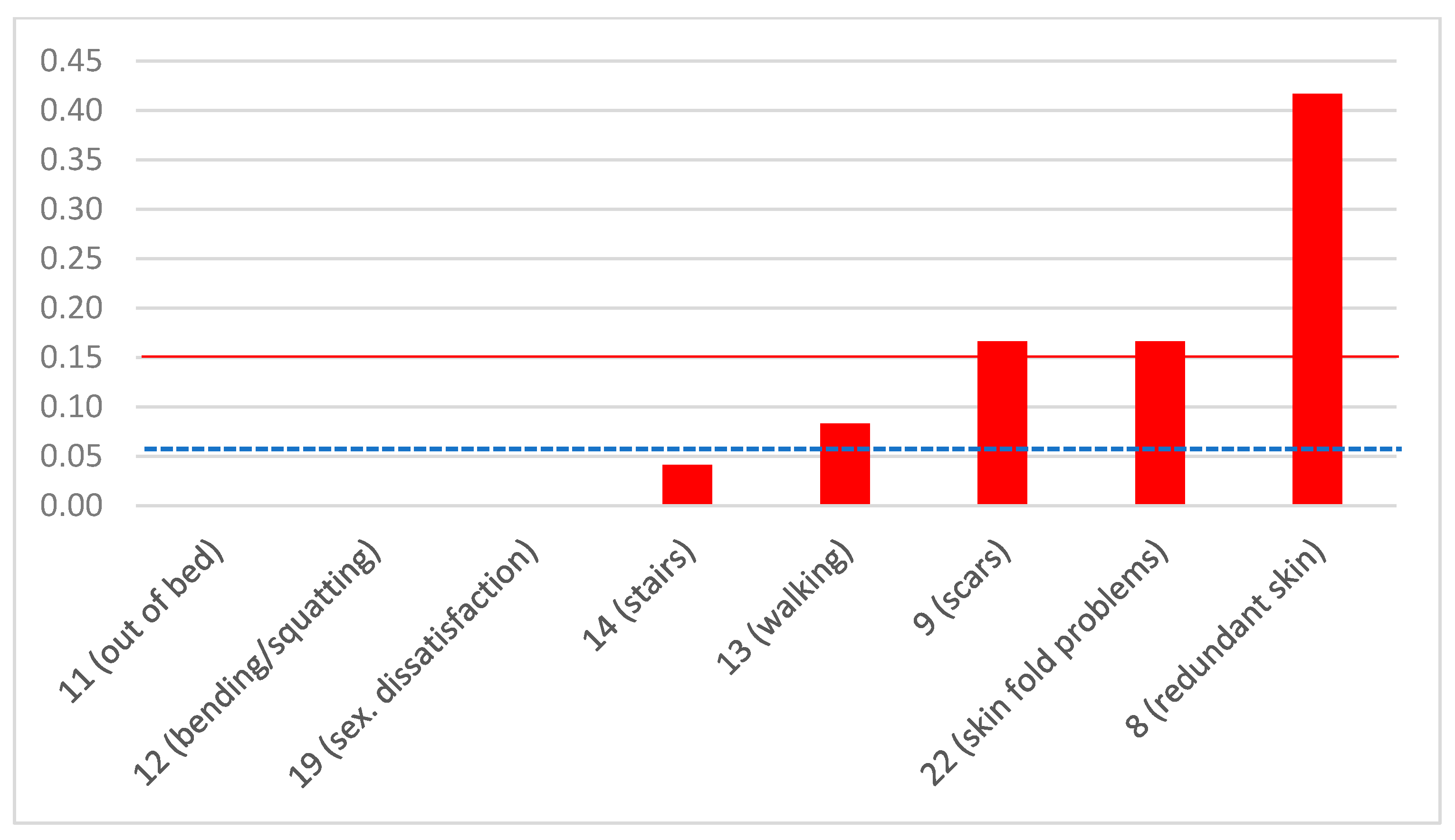

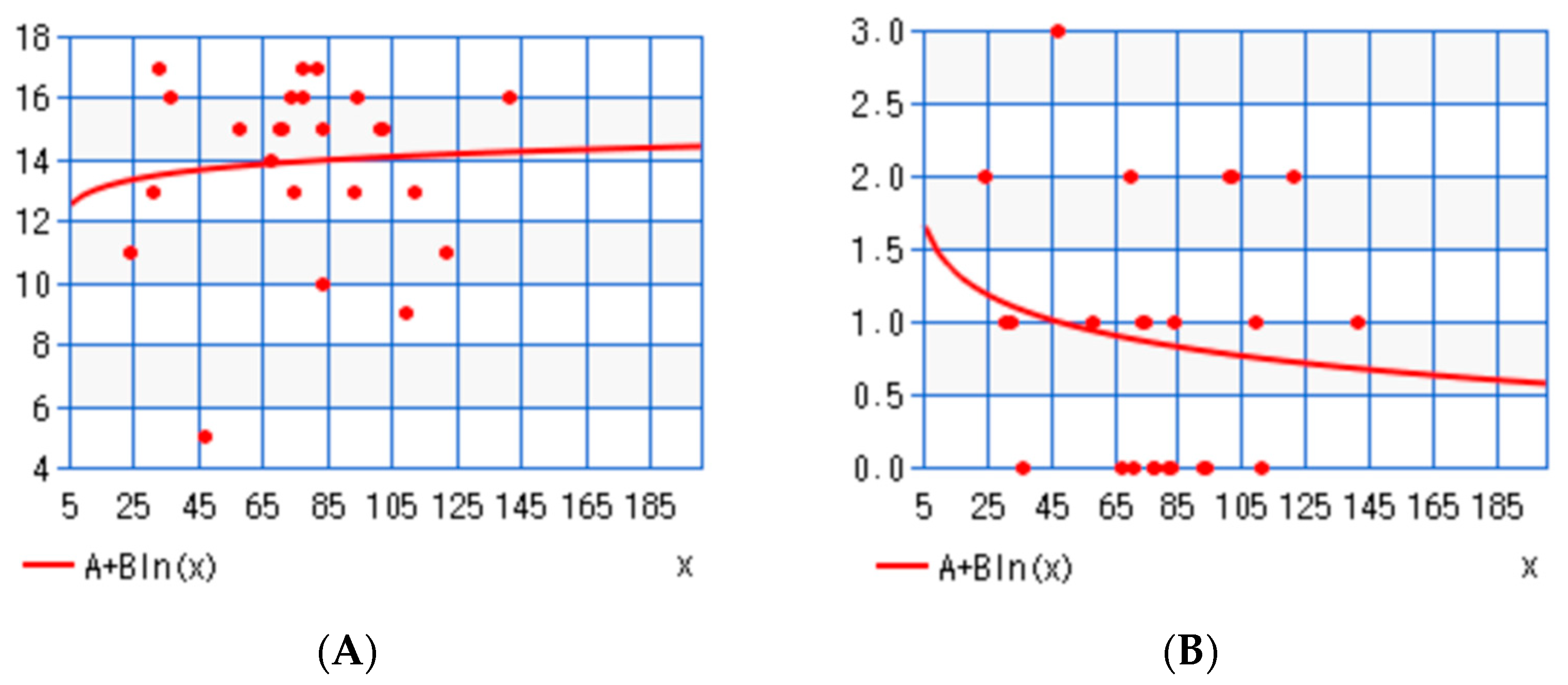

3. Results

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mingrone, G.; Panunzi, S.; De Gaetano, A.; Guidone, C.; Iaconelli, A.; Leccesi, L.; Nanni, G.; Pomp, A.; Castagneto, M.; Ghirlanda, G.; et al. Bariatric Surgery versus Conventional Medical Therapy for Type 2 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 1577–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schauer, P.R.; Bhatt, D.L.; Kirwan, J.P.; Wolski, K.; Aminian, A.; Brethauer, S.A.; Navaneethan, S.D.; Singh, R.P.; Pothier, C.E.; Nissen, S.E.; et al. Bariatric Surgery versus Intensive Medical Therapy for Diabetes—5-Year Outcomes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 641–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöström, L. Review of the key results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) trial—A prospective controlled intervention study of bariatric surgery. J. Intern. Med. 2013, 273, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobsen, G.S.; Småstuen, M.C.; Sandbu, R.; Nordstrand, N.; Hofsø, D.; Lindberg, M.; Hertel, J.K.; Hjelmesæth, J. Association of Bariatric Surgery vs Medical Obesity Treatment With Long-term Medical Complications and Obesity-Related Comorbidities. JAMA 2018, 319, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apovian, C.M.; Mechanick, J.I. Obesity IS a disease! Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 2013, 20, 367–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, S. Recognizing obesity as a disease. J. Am. Assoc. Nurse Pract. 2020, 32, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenberg, D.; Shikora, S.A.; Aarts, E.; Aminian, A.; Angrisani, L.; Cohen, R.V.; De Luca, M.; Faria, S.L.; Goodpaster, K.P.S.; Haddad, A.; et al. 2022 American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) and International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders (IFSO): Indications for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. Off. J. Am. Soc. Bariatr. Surg. 2022, 18, 1345–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altieri, M.S.; Yang, J.; Park, J.; Novikov, D.; Kang, L.; Spaniolas, K.; Bates, A.; Talamini, M.; Pryor, A. Utilization of Body Contouring Procedures Following Weight Loss Surgery: A Study of 37,806 Patients. Obes. Surg. 2017, 27, 2981–2987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mechanick, J.I.; Apovian, C.; Brethauer, S.; Garvey, W.T.; Joffe, A.M.; Kim, J.; Kushner, R.F.; Lindquist, R.; Pessah-Pollack, R.; Seger, J.; et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the perioperative nutrition, metabolic, and nonsurgical support of patients undergoing bariatric procedures—2019 update: Cosponsored by American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology, The Obesity Society, American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery, Obesity Medicine Association, and American Society of Anesthesiologists. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2020, 16, 175–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElAbd, R.; Samargandi, O.A.; AlGhanim, K.; Alhamad, S.; Almazeedi, S.; Williams, J.; AlSabah, S.; AlYouha, S. Body Contouring Surgery Improves Weight Loss after Bariatric Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2021, 45, 1064–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adami, G.F.; Carbone, F.; Montecucco, F.; Camerini, G.; Cordera, R. Adipose Tissue Composition in Obesity and After Bariatric Surgery. Obes. Surg. 2019, 29, 3030–3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chait, A.; den Hartigh, L.J. Adipose Tissue Distribution, Inflammation and Its Metabolic Consequences, Including Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 7, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labrecque, J.; Laforest, S.; Michaud, A.; Biertho, L.; Tchernof, A. Impact of Bariatric Surgery on White Adipose Tissue Inflammation. Can. J. Diabetes 2017, 41, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, L.; Santosa, S. Putting ATM to BED: How Adipose Tissue Macrophages Are Affected by Bariatric Surgery, Exercise, and Dietary Fatty Acids. Adv. Nutr. Bethesda 2021, 12, 1893–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toma, T.; Harling, L.; Athanasiou, T.; Darzi, A.; Ashrafian, H. Does Body Contouring After Bariatric Weight Loss Enhance Quality of Life? A Systematic Review of QOL Studies. Obes. Surg. 2018, 28, 3333–3341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, M.A.; Opyrchał, J.; Knakiewicz, M.; Jaremków, P.; Duda-Barcik, Ł.; Ibrahim, A.M.S.; Lin, S.J. The long-term effect of body contouring procedures on the quality of life in morbidly obese patients after bariatric surgery. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Z.; Zhang, G.; Huang, J.; Shen, C.; Cai, Z.; Yin, X.; Yin, Y.; Zhang, B. A systematic review of body contouring surgery in post-bariatric patients to determine its prevalence, effects on quality of life, desire, and barriers. Obes. Rev. 2021, 22, e13201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klassen, A.F.; Cano, S.J.; Alderman, A.; Soldin, M.; Thoma, A.; Robson, S.; Kaur, M.; Papas, A.; Van Laeken, N.; Taylor, V.H.; et al. The BODY-Q: A Patient-Reported Outcome Instrument for Weight Loss and Body Contouring Treatments. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2016, 4, e679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldin, M.; Mughal, M.; Al-Hadithy, N.; Department of Health; British association of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgeons; Royal College of Surgeons England. National commissioning guidelines: Body contouring surgery after massive weight loss. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2014, 67, 1076–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherf Dagan, S.; Goldenshluger, A.; Globus, I.; Schweiger, C.; Kessler, Y.; Kowen Sandbank, G.; Ben-Porat, T.; Sinai, T. Nutritional Recommendations for Adult Bariatric Surgery Patients: Clinical Practice12. Adv. Nutr. 2017, 8, 382–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toninello, P.; Montanari, A.; Bassetto, F.; Vindigni, V.; Paoli, A. Nutritional Support for Bariatric Surgery Patients: The Skin beyond the Fat. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sioka, E.; Tzovaras, G.; Katsogridaki, G.; Bakalis, V.; Bampalitsa, S.; Zachari, E.; Zacharoulis, D. Desire for Body Contouring Surgery After Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2015, 39, 978–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfanagely, O.; Rios-Diaz, A.J.; Cunning, J.R.; Othman, S.; Morris, M.; Messa, C.; Broach, R.B.; Fischer, J.P. A Prospective, Matched Comparison of Health-Related Quality of Life in Bariatric Patients following Truncal Body Contouring. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2022, 149, 1338–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinari, G.M.; Anselmino, M.; Tascini, C.; Bernante, P.; Foletto, M.; Gentileschi, P.; Morino, M.; Olmi, S.; Toppino, M.; Silecchia, G. Bariatric and metabolic surgery during COVID-19 outbreak phase 2 in Italy: Why, when and how to restart. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2020, 16, 1614–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasta, A.M.; Goel, R.; Kanagavel, M.; Easwaramoorthy, S. Impact of COVID-19 on General Surgical Practice in India. Indian J. Surg. 2020, 82, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhasker, A.G.; Khaitan, M.; Bindal, V.; Kumar, A.; Rajkumar, A.; Kaushal, A.; Prasad, A.; Parikh, C.; Sethi, D.; Goel, D.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on bariatric surgery in India: An obesity and metabolic surgery society of India survey of 1307 patients. J. Minimal Access Surg. 2021, 17, 542–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; More, A.; Harikar, M. The Impact of COVID-19 and Lockdown on Plastic Surgery Training and Practice in India. Indian J. Plast. Surg. 2020, 53, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uccelli, M.; Cesana, G.C.; De Carli, S.M.; Ciccarese, F.; Oldani, A.; Zanoni, A.A.G.; Giorgi, R.; Villa, R.; Ismail, A.; Targa, S.; et al. COVID-19 and Obesity: Is Bariatric Surgery Protective? Retrospective Analysis on 2145 Patients Undergone Bariatric-Metabolic Surgery from High Volume Center in Italy (Lombardy). Obes. Surg. 2021, 31, 942–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, R.; Ludwig, C.; Rudge, G.; Gkoutos, G.V.; Tahrani, A.; Mahawar, K.; Pędziwiatr, M.; Major, P.; Zarzycki, P.; Pantelis, A.; et al. 30-Day Morbidity and Mortality of Bariatric Surgery During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Multinational Cohort Study of 7704 Patients from 42 Countries. Obes. Surg. 2021, 31, 4272–4288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arterburn, D.E.; Telem, D.A.; Kushner, R.F.; Courcoulas, A.P. Benefits and Risks of Bariatric Surgery in Adults: A Review. JAMA 2020, 324, 879–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cintra Junior, W.; Modolin, M.L.A.; Colferai, D.R.; Rocha, R.I.; Gemperli, R. Post-bariatric body contouring surgery: Analysis of complications in 180 consecutive patients. Rev. Col. Bras. Cir. 2021, 48, e20202638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Paep, K.; Van Campenhout, I.; Van Cauwenberge, S.; Dillemans, B. Post-bariatric Abdominoplasty: Identification of Risk Factors for Complications. Obes. Surg. 2021, 31, 3203–3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marouf, A.; Mortada, H. Complications of Body Contouring Surgery in Postbariatric Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2021, 45, 2810–2820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadeghi, P.; Duarte-Bateman, D.; Ma, W.; Khalaf, R.; Fodor, R.; Pieretti, G.; Ciccarelli, F.; Harandi, H.; Cuomo, R. Post-Bariatric Plastic Surgery: Abdominoplasty, the State of the Art in Body Contouring. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhaiem, R.; Maghrebi, H.; Rebai, W.; Makni, A.; Ksantini, R.; Ben Safta, Z. Long term results of laparoscopic gastric band. Tunis. Med. 2017, 95, 440–443. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, P.E.; Hindle, A.; Brennan, L.; Skinner, S.; Burton, P.; Smith, A.; Crosthwaite, G.; Brown, W. Long-Term Outcomes After Bariatric Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Weight Loss at 10 or More Years for All Bariatric Procedures and a Single-Centre Review of 20-Year Outcomes After Adjustable Gastric Banding. Obes. Surg. 2019, 29, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item No. | Question | Answer | Type of Question |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Are you satisfied with how your body looks when you wear a swimsuit? | YES/NO | Positive |

| 2 | Are you satisfied with how your clothes fit your belly? | YES/NO | Positive |

| 3 | Are you satisfied with how your clothes are shaped by your arms? | YES/NO | Positive |

| 4 | Are you satisfied with your back looks when you are naked? | YES/NO | Positive |

| 5 | Are you satisfied with how your buttocks appear? | YES/NO | Positive |

| 6 | Are you satisfied with the shape of your thighs? | YES/NO | Positive |

| 7 | Are you satisfied with the looks of the inner surface of your thighs? | YES/NO | Positive |

| 8 | Are you annoyed by how others look at your redundant skin? | YES/NO | Negative |

| 9 | Are you annoyed by how visible your scars are? | YES/NO | Negative |

| 10 | Do you agree with the statement: “my body is not perfect, but I like it”? | YES/NO | Positive |

| 11 | Do you have difficulty getting out of bed? | YES/NO | Negative |

| 12 | Do you have difficulty bending or squatting (i.e., to tie your laces)? | YES/NO | Negative |

| 13 | Do you have difficulty walking? | YES/NO | Negative |

| 14 | Do you have difficulty climbing stairs? | YES/NO | Negative |

| 15 | Can you stand up for a long time? | YES/NO | Positive |

| 16 | Are you self-confident? | YES/NO | Positive |

| 17 | Do you feel comfortable when you are naked in front of your partner? | YES/NO | Positive |

| 18 | Are you satisfied with your sexual life? | YES/NO | Positive |

| 19 | If the answer to the previous question is NO, do you consider that your appearance after the bariatric operation is responsible? | YES/NO | Negative |

| 20 | Do you feel attractive when naked? | YES/NO | Positive |

| 21 | Do you participate in social activities? | YES/NO | Positive |

| 22 | Do you have irritation, rash, or itching in any skin fold of yours? | YES/NO | Negative |

| 23 | Do you think that your doctor had a comprehensive discussion with you? | YES/NO | Positive |

| 24 | Did your doctor answer all your queries regarding your BCS? | YES/NO | Positive |

| 25 | Do you feel that your doctor treated you according to your expectations? | YES/NO | Positive |

| Characteristic | Both Groups N = 24 ±SD, (%) | Group 1 N = 5 ±SD, (%) | Group 2 N = 19 ±SD, (%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 41.2 ± 7.35 | 40.2 ± 9.96 | 41.5 ± 7.04 | 0.889 (U = 45) |

| Gender (female) | 17 (70.8) | 4 (80.0) | 13 (68.4) | 1.000 |

| Residence (Athens) | 17 (70.8) | 4 (80.0) | 13 (68.4) | 1.000 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 6 (25) | 2 (40.0) | 4 (21.1) | 0.568 |

| Married | 16 (66.7) | 2 (40.0) | 14 (72.7) | 0.289 |

| Divorced | 2 (16.7) | 1 (20.0) | 1 (5.3) | 0.380 |

| BMI | ||||

| Before MBS (kg/m2) | 43.8 ± 9.86 | 46.9 ± 7.02 | 42.2 ± 10.48 | 0.412 (U = 35.5) |

| 1 year post-MBS (kg/m2) | 28.6 ± 4.25 | 26.9 ± 6.68 | 29.1 ± 3.63 | 0.569 (U = 39) |

| Before BCS (kg/m2) | 28.6 ± 4.27 | 26.5 ± 5.00 | 29.3 ± 4.13 | 0.201 (U = 29) |

| Maximum (kg/m2) | 44.3 ± 10.96 | 49.0 ± 8.88 | 43.1 ± 11.61 | 0.242 (U = 30.5) |

| Minimum (kg/m2) | 25.6 ± 3.40 | 24.8 ± 5.97 | 25.8 ± 2.70 | 0.254 (U = 31) |

| At interview (kg/m2) | 28.0 ± 4.71 | 27.0 ± 7.66 | 28.3 ± 4.02 | 0.284 (U = 32) |

| Associated health problems | ||||

| Hypertension | 8 (33) | 2 (40.0) | 6 (31.6) | 1.000 |

| Dyslipidemia | 3 (12.5) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (15.8) | 1.000 |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 1 (4.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.3) | 1.000 |

| Anemia | 3 (12.5) | 2 (40.0) | 1 (5.3) | 0.099 |

| COVID-19 | 22 (91.7) | 4 (80.0) | 18 (94.7) | 0.380 |

| Smoking | 18 (75.0) | 3 (60.0) | 15 (78.9) | 0.568 |

| Alcohol (social consumption) | 13 (54.2) | 3 (60.0) | 10 (52.6) | 1.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pantelis, A.G.; Vakis, G.; Kotrotsiou, M.; Lapatsanis, D.P. Status of Body Contouring Following Metabolic Bariatric Surgery in a Tertiary Hospital of Greece—Still a Long Way to Go. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3196. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12093196

Pantelis AG, Vakis G, Kotrotsiou M, Lapatsanis DP. Status of Body Contouring Following Metabolic Bariatric Surgery in a Tertiary Hospital of Greece—Still a Long Way to Go. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(9):3196. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12093196

Chicago/Turabian StylePantelis, Athanasios G., Georgios Vakis, Maria Kotrotsiou, and Dimitris P. Lapatsanis. 2023. "Status of Body Contouring Following Metabolic Bariatric Surgery in a Tertiary Hospital of Greece—Still a Long Way to Go" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 9: 3196. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12093196

APA StylePantelis, A. G., Vakis, G., Kotrotsiou, M., & Lapatsanis, D. P. (2023). Status of Body Contouring Following Metabolic Bariatric Surgery in a Tertiary Hospital of Greece—Still a Long Way to Go. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(9), 3196. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12093196