Development of an Italian National Epidemiological Register on Endometriosis Based on Administrative Data

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

Statistical Analysis

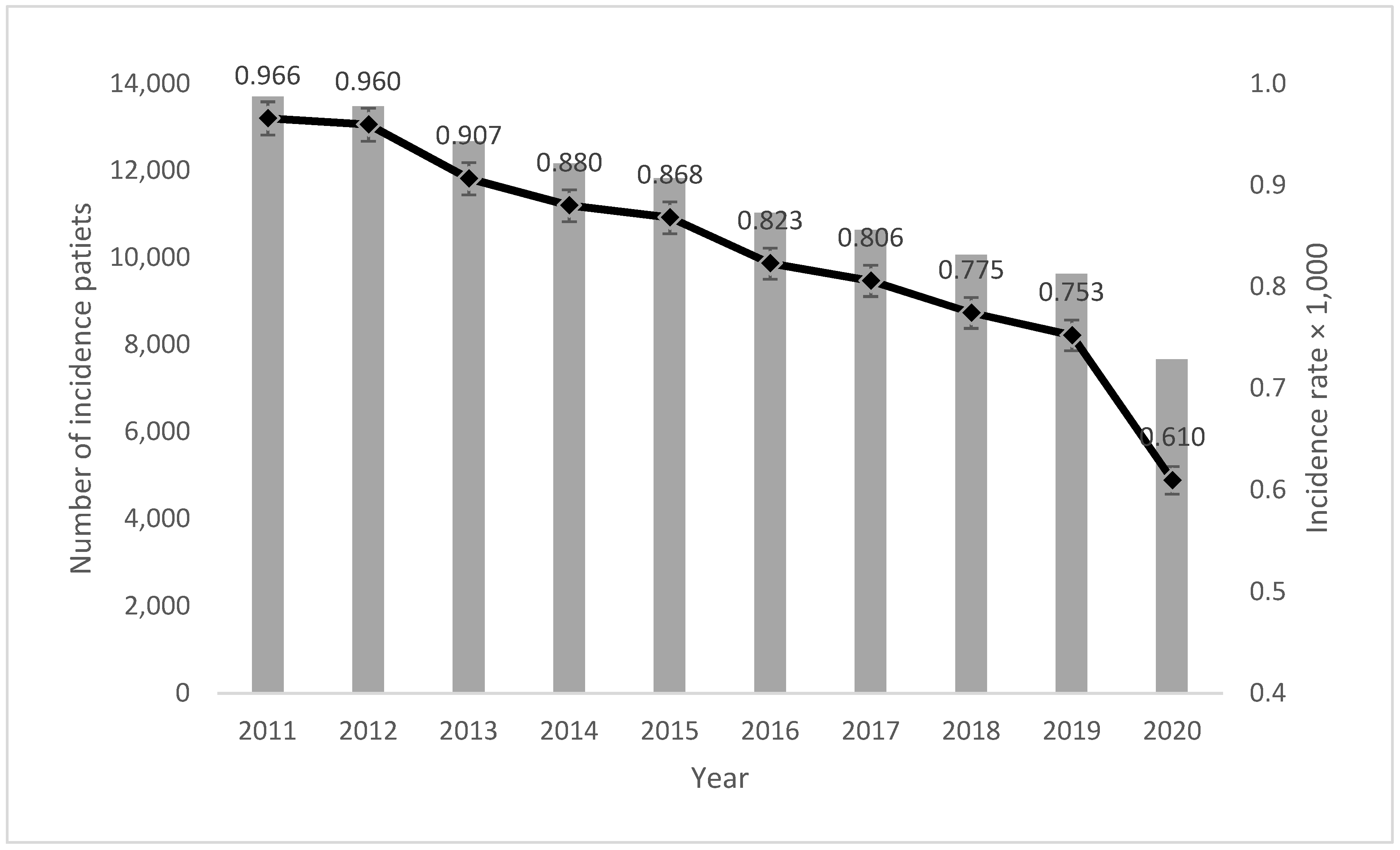

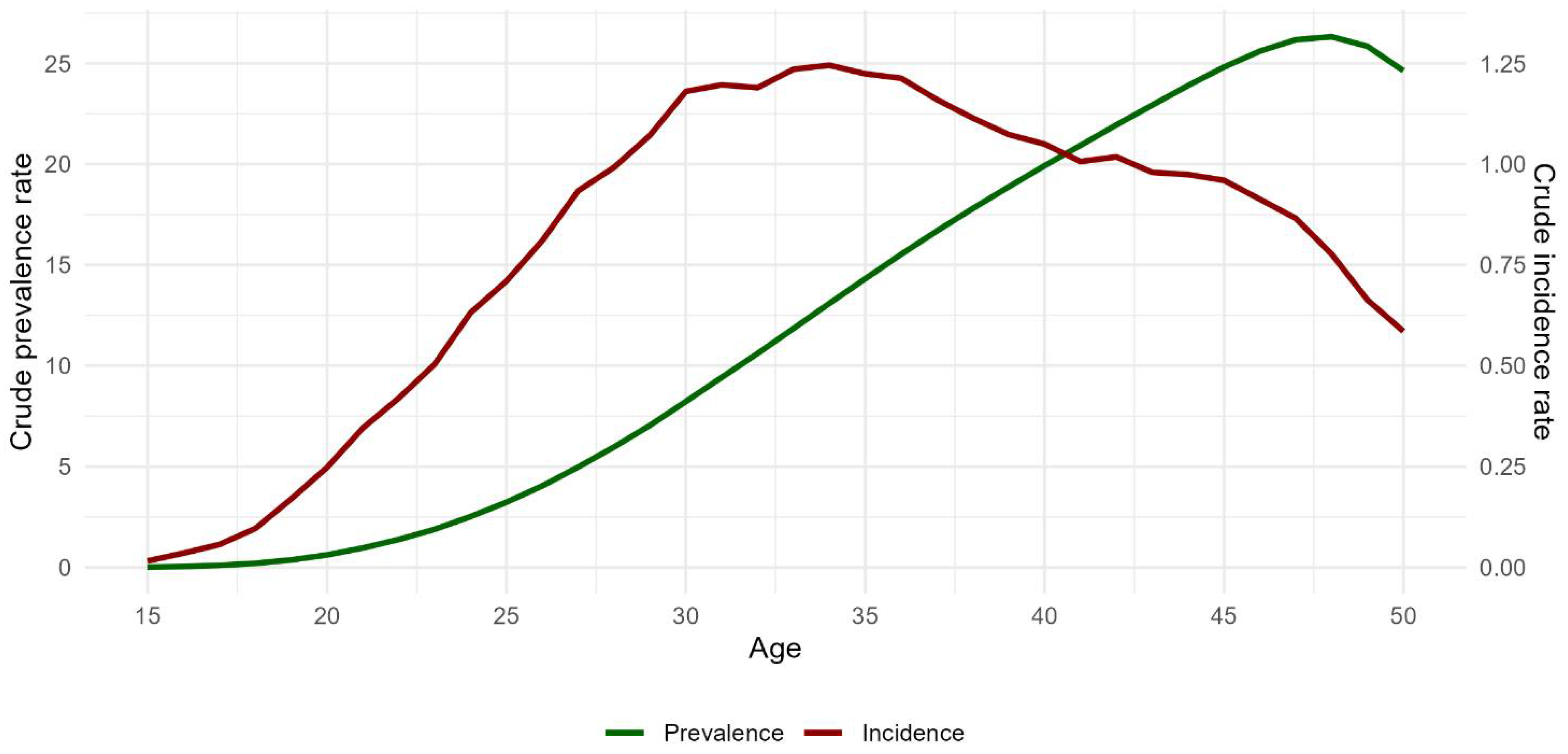

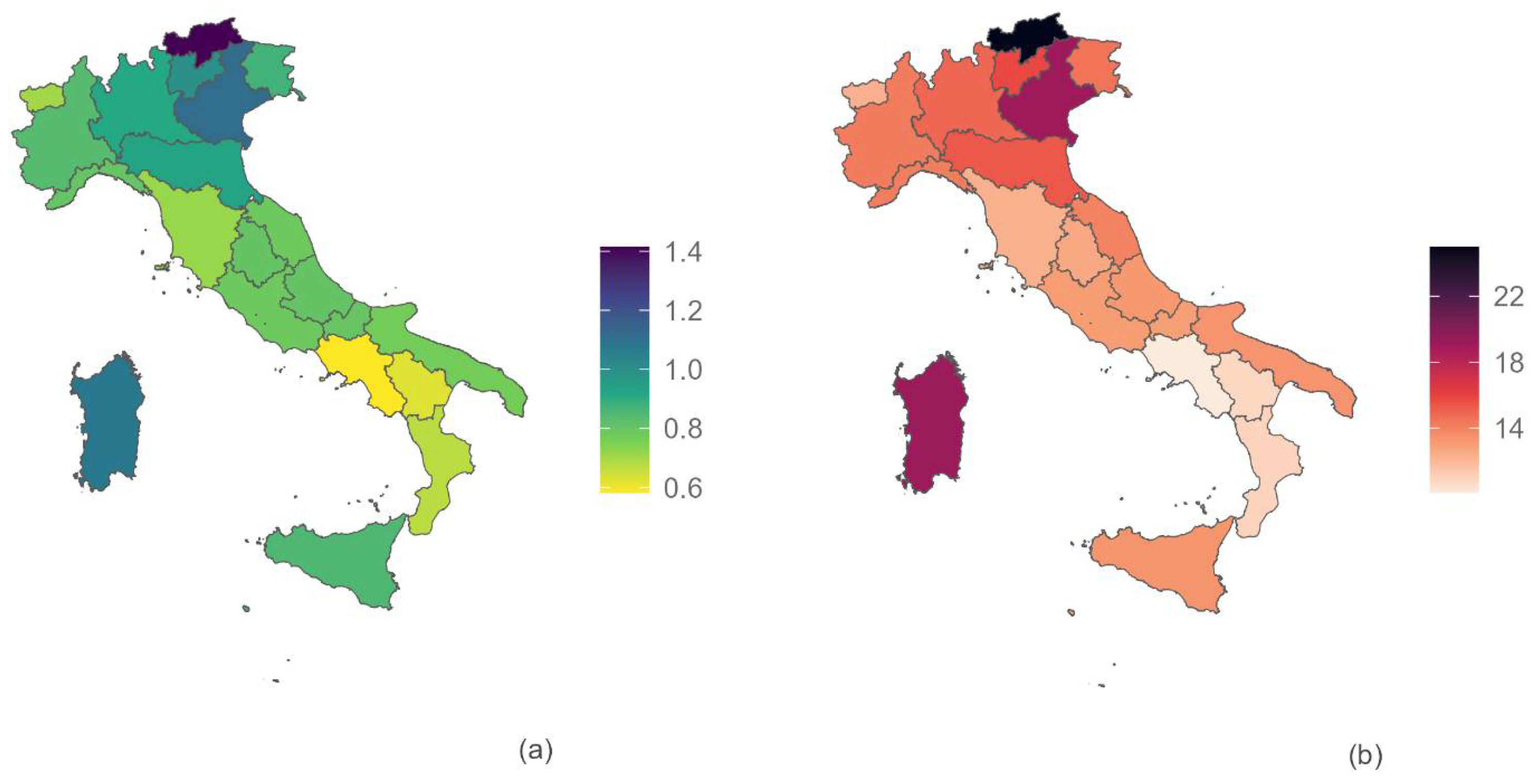

3. Results

Sensitivity Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal Results

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

4.3. Interpretation and Comparison with Prior Work

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Acronyms

References

- Zondervan, K.T.; Becker, C.M.; Missmer, S.A. Endometriosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1244–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- As-Sanie, S.; Black, R.; Giudice, L.C.; Gray Valbrun, T.; Gupta, J.; Jones, B.; Laufer, M.R.; Milspaw, A.T.; Missmer, S.A.; Norman, A.; et al. Assessing research gaps and unmet needs in endometriosis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 221, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nnoaham, K.E.; Hummelshoj, L.; Webster, P.; d’Hooghe, T.; de Cicco Nardone, F.; de Cicco Nardone, C.; Jenkinson, C.; Kennedy, S.H.; Zondervan, K.T.; World Endometriosis Research Foundation Global Study of Women’s Health Consortium. Impact of endometriosis on quality of life and work productivity: A multicenter study across ten countries. Fertil. Steril. 2011, 96, 366–373.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, C.M.; Bokor, A.; Heikinheimo, O.; Horne, A.; Jansen, F.; Kiesel, L.; King, K.; Kvaskoff, M.; Nap, A.; Petersen, K.; et al. ESHRE Endometriosis Guideline Group. ESHRE guideline: Endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. Open 2022, 2022, hoac009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudson, N. The missed disease? Endometriosis as an example of ‘undone science’. Reprod. Biomed. Soc. Online 2021, 14, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas, S.; Ihle, P.; Köster, I.; Schubert, I. Prevalence and incidence of diagnosed endometriosis and risk of endometriosis in patients with endometriosis-related symptoms: Findings from a statutory health insurance-based cohort in Germany. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2012, 160, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowlands, I.J.; Abbott, J.A.; Montgomery, G.W.; Hockey, R.; Rogers, P.; Mishra, G.D. Prevalence and incidence of endometriosis in Australian women: A data linkage cohort study. BJOG 2021, 128, 657–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ávalos Marfil, A.; Barranco Castillo, E.; Martos García, R.; Mendoza Ladrón de Guevara, N.; Mazheika, M. Epidemiology of Endometriosis in Spain and Its Autonomous Communities: A Large, Nationwide Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarria-Santamera, A.; Orazumbekova, B.; Terzic, M.; Issanov, A.; Chaowen, C.; Asúnsolo-Del-Barco, A. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Incidence and Prevalence of Endometriosis. Healthcare 2020, 9, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morassutto, C.; Monasta, L.; Ricci, G.; Barbone, F.; Ronfani, L. Incidence and Estimated Prevalence of Endometriosis and Adenomyosis in Northeast Italy: A Data Linkage Study. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0154227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministero della Salute. Direzione Generale della Programmazione Sanitaria Ufficio 6. Rapporto Annuale sull’Attività di Ricovero Ospedaliero. Available online: https://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_3410_allegato.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- Dunselman, G.A.; Vermeulen, N.; Becker, C.; Calhaz-Jorge, C.; D’Hooghe, T.; De Bie, B.; Heikinheimo, O.; Horne, A.W.; Kiesel, L.; Nap, A.; et al. ESHRE guideline: Management of women with endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 2014, 29, 400–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISTAT Popolazione Residente. Available online: http://dati.istat.it/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=DCIS_POPRES1 (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- Pino, I.; Belloni, G.M.; Barbera, V.; Solima, E.; Radice, D.; Angioni, S.; Arena, S.; Bergamini, V.; Candiani, M.; Maiorana, A.; et al. “Better late than never but never late is better”, especially in young women. A multicenter Italian study on diagnostic delay for symptomatic endometriosis. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 2023, 28, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, F.F.; Du, H.; Goldstein, G.P.; Beaumont, J.L.; Zhou, Y.; Brown, W.J. The influence of prior oral contraceptive use on risk of endometriosis is conditional on parity. Fertil. Steril. 2014, 101, 1697–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, H.S.; Adamson, G.D.; Diamond, M.P.; Goldstein, S.R.; Horne, A.W.; Missmer, S.A.; Snabes, M.C.; Surrey, E.; Taylor, R.N. An evidence-based approach to assessing surgical versus clinical diagnosis of symptomatic endometriosis. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2018, 142, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrero, S.; Arena, E.; Morando, A.; Remorgida, V. Prevalence of newly diagnosed endometriosis in women attending the general practitioner. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2010, 110, 203–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Migliaretti, G.; Deltetto, F.; Delpiano, E.M.; Bonino, L.; Berchialla, P.; Dalmasso, P.; Cavallo, F.; Camanni, M. Spatial analysis of the distribution of endometriosis in northwestern Italy. Gynecol. Obstet. Investig. 2012, 73, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saavalainen, L.; Lassus, H.; But, A.; Tiitinen, A.; Härkki, P.; Gissler, M.; Heikinheimo, O.; Pukkala, E. A Nationwide Cohort Study on the risk of non-gynecological cancers in women with surgically verified endometriosis. Int. J. Cancer 2018, 143, 2725–2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Gong, T.T.; Wang, H.Y.; Zhao, Y.H.; Wu, Q.J. Global, regional, and national endometriosis trends from 1990 to 2017. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2021, 1484, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christ, J.P.; Yu, O.; Schulze-Rath, R.; Grafton, J.; Hansen, K.; Reed, S.D. Incidence, prevalence, and trends in endometriosis diagnosis: A United States population-based study from 2006 to 2015. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 225, 500.e1–500.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motan, T.; Antaki, R.; Han, J.; Elliott, J.; Cockwell, H. Guideline No. 435: Minimally Invasive Surgery in Fertility Therapy. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2023, 45, 273–282.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agenzia Nazionale per i Servizi Sanitari Regionali. Available online: https://endometriosi.agenas.it/ (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- Rapporto Osservasalute 2022. Available online: https://osservatoriosullasalute.it/osservasalute/rapporto-osservasalute-2022 (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- Agenzia per la Coesione Territoriale; Nucleo di Verifica e Controllo (NUVEC). La Spesa in Sanità: I dati CPT per un’Analisi in Serie Storica a Livello Territoriale, CPT Informa n. 3/2020. Available online: https://www.agenziacoesione.gov.it/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/CPT_Informa_Sanitax.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- Vallée, A.; Ceccaldi, P.F.; Carbonnel, M.; Feki, A.; Ayoubi, J.M. Pollution and endometriosis: A deep dive into the environmental impacts on women’s health. BJOG 2023, 131, 401–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cano-Sancho, G.; Ploteau, S.; Matta, K.; Adoamnei, E.; Louis, G.B.; Mendiola, J.; Darai, E.; Squifflet, J.; Le Bizec, B.; Antignac, J.P. Human epidemiological evidence about the associations between exposure to organochlorine chemicals and endometriosis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Int. 2019, 123, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upson, K. Environmental risk factors for endometriosis: A critical evaluation of studies and recommendations from the epidemiologic perspective. Curr. Epidemiol. Rep. 2020, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| ICD-9-CM Diagnosis Code | ICD-9-CM Procedure Code | |

|---|---|---|

| 617 or 617.0 or 617.1 or 617.2 or 617.3 or 617.4 or 617.5 or 617.6 or 617.8 or 617.9 | AND | 34.81 or 37.34 or 45.23 or 45.24 or 45.26 or 45.62 or 45.72 or 45.76 or 45.94 or 46.04 or 46.11 or 46.21 or 47.01 or 47.19 or 47.99 or 48.62 or 48.63 or 48.69 or 48.82 or 49.39 or 51.23 or 54.11 or 54.12 or 54.19 or 54.21 or 54.23 or 54.24 or 54.4 or 54.51 or 54.59 or 54.73 or 55.51 or 56.74 or 56.99 or 57.32 or 57.6 or 57.99 or 59.00 or 59.02 or 59.03 or 65.01 or 65.12 or 65.13 or 65.23 or 65.24 or 65.25 or 65.29 or 65.31 or 65.41 or 65.49 or 65.51 or 65.52 or 65.53 or 65.54 or 65.61 or 65.62 or 65.63 or 65.74 or 65.79 or 65.81 or 65.89 or 65.91 or 65.99 or 66.19 or 66.29 or 66.39 or 66.4 or 66.51 or 66.52 or 66.61 or 66.62 or 66.63 or 66.69 or 67.39 or 67.4 or 68.12 or 68.13 or 68.14 or 68.15 or 68.16 or 68.29 or 68.39 or 68.41 or 68.49 or 68.51 or 68.59 or 68.61 or 68.69 or 68.71 or 68.9 or 69.19 or 69.29 or 70.32 or 70.77 or 86.3 or 87.83 or 97.83 |

| Region | Incidence Annual Rate ×1000 | Total 2011–2020 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | n | Rate | 95% CI | |

| Piemonte | 1.064 | 1.022 | 0.878 | 0.937 | 0.841 | 0.771 | 0.688 | 0.766 | 0.835 | 0.540 | 7810 | 0.840 | (0.822–0.859) |

| Valle D‘Aosta | 0.549 | 0.587 | 1.247 | 0.876 | 0.679 | 0.657 | 0.746 | 0.495 | 0.775 | 0.395 | 194 | 0.705 | (0.609–0.812) |

| Lombardia | 1.118 | 1.068 | 1.001 | 0.942 | 0.941 | 0.930 | 0.945 | 0.856 | 0.687 | 0.597 | 20,126 | 0.912 | (0.900–0.925) |

| Liguria | 0.964 | 1.051 | 0.958 | 0.853 | 0.721 | 0.778 | 0.758 | 0.532 | 0.754 | 0.561 | 2504 | 0.801 | (0.770–0.833) |

| Northwest | 1.085 | 1.050 | 0.966 | 0.932 | 0.892 | 0.872 | 0.859 | 0.801 | 0.732 | 0.577 | 30,634 | 0.881 | (0.871–0.891) |

| PA Bolzano | 1.677 | 1.867 | 1.762 | 1.688 | 1.651 | 1.374 | 1.158 | 1.014 | 0.997 | 0.884 | 1706 | 1.414 | (1.348–1.483) |

| PA Trento | 1.259 | 1.051 | 1.149 | 1.212 | 1.001 | 0.888 | 0.797 | 0.943 | 0.993 | 0.689 | 1198 | 1.002 | (0.946–1.060) |

| Veneto | 1.208 | 1.212 | 1.144 | 1.159 | 1.211 | 1.182 | 1.035 | 1.060 | 1.049 | 0.879 | 12,085 | 1.117 | (1.098–1.138) |

| Friuli-Venezia Giulia | 1.074 | 0.952 | 0.882 | 0.864 | 0.830 | 0.921 | 0.799 | 0.808 | 0.905 | 0.695 | 2225 | 0.876 | (0.840–0.913) |

| Emilia Romagna | 1.017 | 1.059 | 0.972 | 1.015 | 0.972 | 0.930 | 0.934 | 0.840 | 0.839 | 0.672 | 8963 | 0.928 | (0.909–0.947) |

| Northeast | 1.147 | 1.151 | 1.082 | 1.102 | 1.093 | 1.055 | 0.968 | 0.943 | 0.949 | 0.772 | 26,177 | 1.030 | (1.017–1.042) |

| Toscana | 0.938 | 0.885 | 0.804 | 0.791 | 0.683 | 0.607 | 0.596 | 0.668 | 0.646 | 0.495 | 5732 | 0.716 | (0.698–0.735) |

| Umbria | 0.837 | 0.981 | 1.001 | 0.976 | 0.901 | 0.722 | 0.736 | 0.661 | 0.651 | 0.492 | 1532 | 0.802 | (0.763–0.844) |

| Marche | 0.887 | 0.815 | 0.931 | 0.865 | 0.779 | 0.649 | 0.808 | 0.763 | 0.748 | 0.572 | 2616 | 0.785 | (0.755–0.816) |

| Lazio | 0.980 | 0.937 | 0.869 | 0.803 | 0.790 | 0.721 | 0.721 | 0.699 | 0.661 | 0.629 | 10,346 | 0.784 | (0.769–0.799) |

| Centre | 0.945 | 0.909 | 0.867 | 0.820 | 0.764 | 0.678 | 0.695 | 0.695 | 0.667 | 0.572 | 20,226 | 0.765 | (0.754–0.776) |

| Abruzzo | 0.780 | 0.872 | 0.916 | 0.830 | 0.888 | 0.802 | 0.743 | 0.860 | 0.746 | 0.584 | 2355 | 0.805 | (0.773–0.838) |

| Molise | 0.742 | 0.910 | 0.774 | 0.686 | 0.742 | 0.907 | 0.776 | 0.655 | 0.673 | 1.145 | 538 | 0.799 | (0.733–0.869) |

| Campania | 0.633 | 0.659 | 0.650 | 0.609 | 0.586 | 0.551 | 0.587 | 0.532 | 0.557 | 0.429 | 8155 | 0.582 | (0.569–0.594) |

| Puglia | 0.801 | 0.800 | 0.802 | 0.785 | 0.823 | 0.821 | 0.743 | 0.776 | 0.724 | 0.578 | 7189 | 0.768 | (0.750–0.786) |

| Basilicata | 0.571 | 0.849 | 0.706 | 0.649 | 0.616 | 0.574 | 0.683 | 0.608 | 0.513 | 0.442 | 799 | 0.625 | (0.582–0.670) |

| Calabria | 0.692 | 0.755 | 0.756 | 0.664 | 0.728 | 0.653 | 0.704 | 0.650 | 0.605 | 0.487 | 3031 | 0.673 | (0.649–0.697) |

| South | 0.702 | 0.744 | 0.737 | 0.690 | 0.705 | 0.673 | 0.669 | 0.652 | 0.628 | 0.508 | 22,067 | 0.673 | (0.665–0.682) |

| Sicilia | 0.955 | 0.923 | 0.847 | 0.863 | 0.909 | 0.833 | 0.849 | 0.781 | 0.867 | 0.659 | 9899 | 0.851 | (0.835–0.868) |

| Sardegna | 1.174 | 1.219 | 1.147 | 1.056 | 1.176 | 1.122 | 1.085 | 1.012 | 0.945 | 0.812 | 3942 | 1.081 | (1.048–1.115) |

| Islands | 1.008 | 0.994 | 0.919 | 0.909 | 0.972 | 0.902 | 0.905 | 0.835 | 0.885 | 0.695 | 13,841 | 0.906 | (0.891–0.921) |

| ITALY | 0.966 | 0.960 | 0.907 | 0.880 | 0.868 | 0.823 | 0.806 | 0.775 | 0.753 | 0.610 | 112,945 | 0.839 | (0.834–0.844) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maraschini, A.; Ceccarelli, E.; Giangreco, M.; Monasta, L.; Manno, V.; Catelan, D.; Stoppa, G.; Biggeri, A.; Ricci, G.; Buonomo, F.; et al. Development of an Italian National Epidemiological Register on Endometriosis Based on Administrative Data. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3087. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13113087

Maraschini A, Ceccarelli E, Giangreco M, Monasta L, Manno V, Catelan D, Stoppa G, Biggeri A, Ricci G, Buonomo F, et al. Development of an Italian National Epidemiological Register on Endometriosis Based on Administrative Data. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(11):3087. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13113087

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaraschini, Alice, Emiliano Ceccarelli, Manuela Giangreco, Lorenzo Monasta, Valerio Manno, Dolores Catelan, Giorgia Stoppa, Annibale Biggeri, Giuseppe Ricci, Francesca Buonomo, and et al. 2024. "Development of an Italian National Epidemiological Register on Endometriosis Based on Administrative Data" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 11: 3087. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13113087

APA StyleMaraschini, A., Ceccarelli, E., Giangreco, M., Monasta, L., Manno, V., Catelan, D., Stoppa, G., Biggeri, A., Ricci, G., Buonomo, F., Minelli, G., & Ronfani, L. (2024). Development of an Italian National Epidemiological Register on Endometriosis Based on Administrative Data. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(11), 3087. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13113087