Endometriosis and Adenomyosis: Modern Concepts of Their Clinical Outcomes, Treatment, and Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

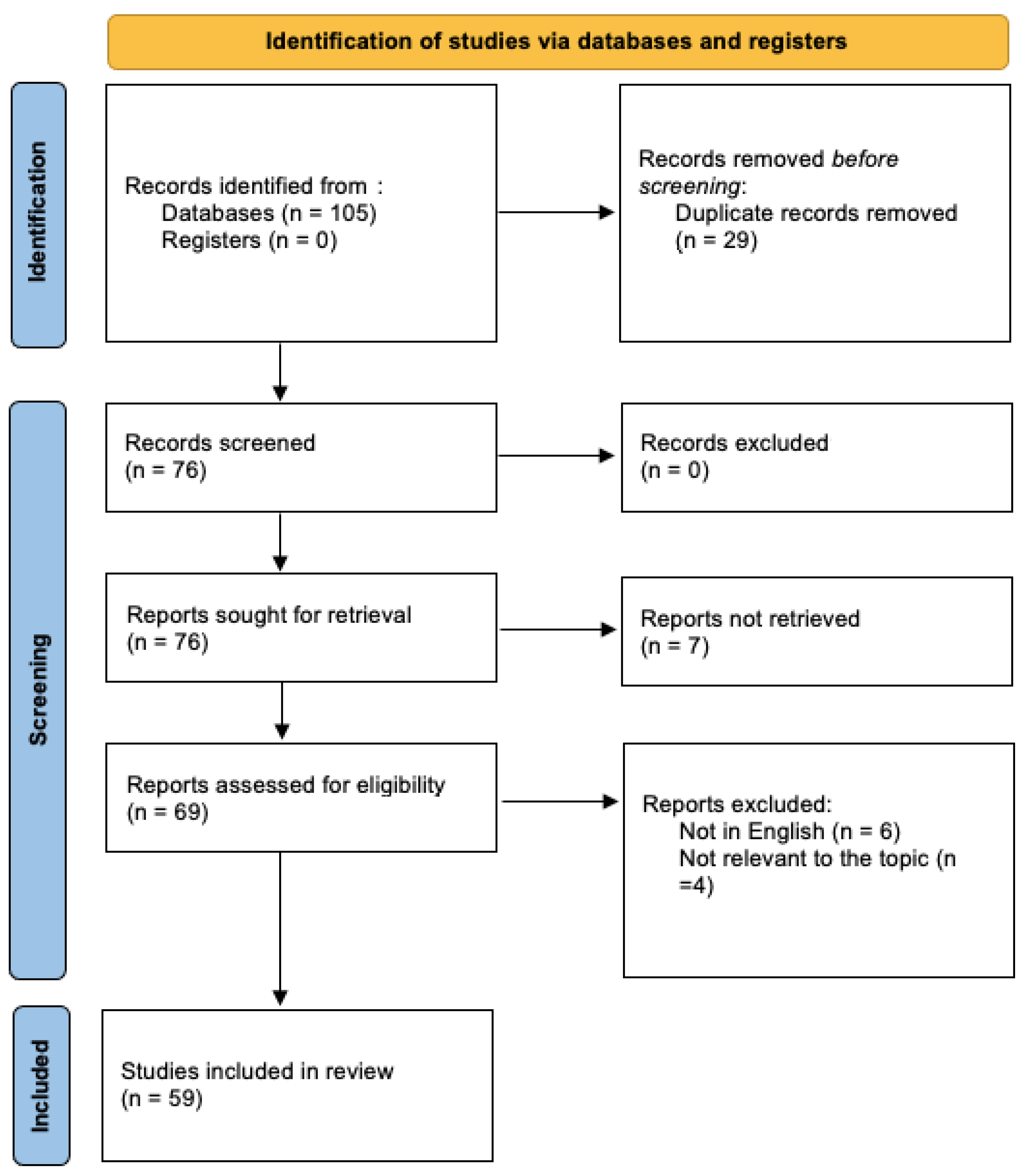

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Endometriosis

3.1.1. Ovarian Endometriosis

Management, Treatment, and Clinical Outcomes

3.1.2. Superficial Peritoneal Endometriosis

Management, Treatment, and Clinical Outcomes

3.1.3. Deep Infiltrating Endometriosis

Management, Treatment, and Clinical Outcomes

3.2. Adenomyosis

- Identification of the presence of adenomyosis using the MUSA criteria [67];

- Determination of the location of the adenomyosis;

- Differentiation between focal and diffuse disease;

- Discrimination between cystic and non-cystic lesions;

- Determination of myometrial layer involvement;

- Classification of disease extent as mild, moderate, or severe;

- Measurement of lesion size.

Management, Treatment, and Clinical Outcome

3.3. Alternative Approaches for Managing Endometriosis-Related Symptoms

- Dietary Changes: Certain diets, such as an anti-inflammatory diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and healthy fats, may help alleviate symptoms. Some people find relief by avoiding trigger foods like dairy or gluten.

- Acupuncture: Acupuncture, a traditional Chinese medicine practice, involves inserting thin needles into specific points on the body to alleviate pain and promote relaxation. Some women with endometriosis find acupuncture helpful for managing pain and stress.

- Herbal Supplements: Certain herbs like turmeric, ginger, and chasteberry (vitex) are believed to have anti-inflammatory properties and may help reduce pain associated with endometriosis. However, it is essential to consult with a healthcare provider before trying herbal supplements, as they can interact with medications or have side effects.

- Mind–Body Practices: Techniques such as yoga, meditation, and mindfulness can help manage stress, improve sleep quality, and promote relaxation. These practices may help reduce pain and enhance overall well-being in individuals with endometriosis.

- Physical Therapy: Pelvic floor physical therapy can help address pelvic pain and dysfunction associated with endometriosis. Therapists use techniques such as manual therapy, stretching, and strengthening exercises to alleviate pain and improve pelvic function.

- Supplements: Some supplements, such as omega-3 fatty acids, magnesium, and vitamin D, may help reduce inflammation and alleviate symptoms of endometriosis. However, it is essential to consult with a healthcare provider before taking supplements to ensure they are safe and appropriate for one’s specific situation.

- Stress Management: Chronic stress can exacerbate symptoms of endometriosis. Practices like deep breathing exercises, progressive muscle relaxation, and biofeedback can help manage stress levels and reduce the impact of stress on symptoms.

4. Discussion

- Need for Specialized Care: The complexity of endometriosis and adenomyosis necessitates referral to specialized facilities in which patients can benefit from specific high-quality management, from early diagnosis to the treatment of severe disease. Given the significant impact of endometriosis on women’s daily lives and its economic burden, gynecological societies and international organizations advocate for the establishment of expert centers throughout the country, formally accredited by health authorities, ideally as part of a National Health Plan [79].

- Challenges in Managing Infertility: Infertility associated with endometriosis poses a significant challenge. The decision between surgery and in vitro fertilization (IVF) depends on various factors, including previous surgical history, pain symptoms, age, and ovarian reserve. Robust prospective studies, such as multicenter randomized controlled trials (RCTs), are essential to compare the effectiveness of these approaches and guide clinical decision making.

- Ongoing Clinical Trials: The ongoing multicenter RCTs comparing IVF and surgery for ovarian endometriosis and deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE) will provide valuable insights into their respective benefits and risks, particularly in terms of live birth rates [78]. Additionally, this research will also include an experimental part aimed at assessing whether the systemic inflammatory environment of endometriosis may have a detrimental impact on the quality of folliculogenesis and embryological development.

- Future Directions in Adenomyosis Research: Adenomyosis poses unique challenges due to its heterogeneity and limited treatment options, especially in cases in which pregnancy is desired. The lack of RCTs comparing different treatment strategies highlights the need for further research to identify optimal management approaches. Studies investigating the role of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists in improving assisted reproductive technology (ART) outcomes in patients with severe adenomyosis offer promising insights. However, more research is needed to establish standardized protocols and evaluate their efficacy.

- Obstetric Complications: Women with severe endometriosis and adenomyosis face increased risks of obstetric complications, including preeclampsia, antepartum hemorrhage, preterm birth, and miscarriage. Understanding these associations is crucial for optimizing prenatal care and reducing maternal and fetal risks.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Becker, C.M.; Bokor, A.; Heikinheimo, O.; Horne, A.; Jansen, F.; Kiesel, L.; King, K.; Kvaskoff, M.; Nap, A.; Petersen, K.; et al. ESHRE Guidelines: Endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. Open 2022, 2022, hoac009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koninckx, P.R.; Meuleman, C.; Demeyere, S.; Lesaffre, E.; Cornillie, F.J. Suggestive evidence that pelvic endometriosis is a progressive disease, whereas deeply infiltrating endometriosis is associated with pelvic pain. Fertil. Steril. 1991, 55, 759–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saunders, P.T.K.; Horne, A.W. Endometriosis: Etiology, pathobiology, and therapeutic prospects. Cell 2021, 184, 2807–2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, A.M.; Viganò, P.; Somigliana, E.; Panina-Bordignon, P.; Vercellini, P.; Candiani, M. The distinguishing cellular and molecular features of the endometriotic ovarian cyst: From pathophysiology to the potential endometrioma-mediated damage to the ovary. Hum. Reprod. Update 2014, 20, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzii, L.; Di Tucci, C.; Di Feliciantonio, M.; Galati, G.; Verrelli, L.; Di Donato, V.; Marchetti, C.; Panici, P.B. Management of Endometriomas. Semin. Reprod. Med. 2017, 35, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelbaya, T.A.; Nardo, L.G. Evidence-based management of endometrioma. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2011, 23, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vannuccini, S.; Clemenza, S.; Rossi, M.; Petraglia, F. Hormonal treatments for endometriosis: The endocrine background. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2022, 23, 333–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlanda, N.; Somigliana, E.; Viganò, P.; Vercellini, P. Safety of medical treatments for endometriosis. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2016, 15, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vercellini, P.; Viganò, P.; Somigliana, E.; Fedele, L. Endometriosis: Pathogenesis and treatments. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2014, 10, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzii, L.; Di Tucci, C.; Achilli, C.; Di Donato, V.; Musella, A.; Palaia, I.; Panici, P.B. Continuous versus cyclic oral contraceptives after laparoscopic excision of ovarian endometriomas: A systematic review and metaanalysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 214, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcone, T.; Flyckt, R. Clinical Management of Endometriosis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 131, 557–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, H.S.; Giudice, L.C.; Lessey, B.A.; Abrao, M.S.; Kotarski, J.; Archer, D.F.; Diamond, M.P.; Surrey, E.; Johnson, N.P.; Watts, N.B.; et al. Treatment of Endometriosis-Associated Pain with Elagolix, an Oral GnRH Antagonist. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, H.S.; Kotlyar, A.M.; Flores, V.A. Endometriosis is a chronic systemic disease: Clinical challenges and novel innovations. Lancet 2021, 397, 839–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.-T.; Johnson, S.J.; Mitchell, D.; Soliman, A.M.; Vora, J.B.; Agarwal, S.K. Cost–effectiveness of elagolix versus leuprolide acetate for treating moderate-to-severe endometriosis pain in the USA. J. Comp. Eff. Res. 2019, 8, 337–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lessey, B.A.; Gordts, S.; Donnez, O.; Somigliana, E.; Chapron, C.; Garcia-Velasco, J.A.; Donnez, J. Ovarian endometriosis and infertility: In vitro fertilization (IVF) or surgery as the first approach? Fertil. Steril. 2018, 110, 1218–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnez, J. Women with endometrioma-related infertility face a dilemma when choosing the appropriate therapy: Surgery or in vitro fertilization. Fertil. Steril. 2018, 110, 1216–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candiani, M.; Ferrari, S.; Bartiromo, L.; Schimberni, M.; Tandoi, I.; Ottolina, J. Fertility Outcome after CO2 Laser Vaporization versus Cystectomy in Women with Ovarian Endometrioma: A Comparative Study. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2021, 28, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Lee, J.E.; Ku, S.-Y.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, J.G.; Moon, S.Y.; Choi, Y.M. Natural conception rate following laparoscopic surgery in infertile women with endometriosis. Clin. Exp. Reprod. Med. 2013, 40, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somigliana, E.; Benaglia, L.; Paffoni, A.; Busnelli, A.; Vigano, P.; Vercellini, P. Risks of conservative management in women with ovarian endometriomas undergoing IVF. Hum. Reprod. Update 2015, 21, 486–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottolina, J.; Vignali, M.; Papaleo, E.; Viganò, P.; Somigliana, E.; Ferrari, S.; Liprandi, V.; Belloni, G.; Reschini, M.; Candiani, M.; et al. Surgery versus IVF for the treatment of infertility associated to ovarian and deep endometriosis (SVIDOE: Surgery Versus IVF for Deep and Ovarian Endometriosis). Clinical protocol for a multicenter randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0271173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candiani, M.; Ottolina, J.; Posadzka, E.; Ferrari, S.; Castellano, L.M.; Tandoi, I.; Pagliardini, L.; Nocuń, A.; Jach, R. Assessment of ovarian reserve after cystectomy versus ‘one-step’ laser vaporization in the treatment of ovarian endometrioma: A small randomized clinical trial. Hum. Reprod. 2019, 34, 2087–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmona, F.; Martínez-Zamora, M.A.; Rabanal, A.; Martínez-Román, S.; Balasch, J. Ovarian cystectomy versus laser vaporization in the treatment of ovarian endometriomas: A randomized clinical trial with a five-year follow-up. Fertil. Steril. 2011, 96, 251–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tulikangas, P.K.; Smith, T.; Falcone, T.; Boparai, N.; Walters, M.D. Gross and histologic characteristics of laparoscopic injuries with four different energy sources. Fertil. Steril. 2001, 75, 806–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomassetti, C.; Johnson, N.P.; Petrozza, J.; Abrao, M.S.; Einarsson, J.I.; Horne, A.W.; Lee, T.T.M.; Missmer, S.; Vermeulen, N.; International Working Group of AAGL, ESGE, ESHRE and WES; et al. An international terminology for endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. Open 2021, 28, 1849–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horne, A.W.; Daniels, J.; Hummelshoj, L.; Cox, E.; Cooper, K. Surgical removal of superficial peritoneal endometriosis for managing women with chronic pelvic pain: Time for a rethink? BJOG 2019, 126, 1414–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reis, F.M.; Santulli, P. Superficial Peritoneal Endometriosis: Clinical Characteristics of 203 Confirmed Cases and 1292 En-dometriosis-Free Controls. Reprod. Sci. 2020, 27, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koninckx, P.R.; Ussia, A.; Adamyan, L.; Tahlak, M.; Keckstein, J.; Wattiez, A.; Martin, D.C. The epidemiology of endometriosis is poorly known as the pathophysiology and diagnosis are unclear. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2021, 71, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonardi, M.; Gibbons, T.; Armour, M.; Wang, R.; Glanville, E.; Hodgson, R.; Cave, A.E.; Ong, J.; Tong, Y.Y.F.; Jacobson, T.Z.; et al. When to do surgery and when not to do surgery for endometriosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2020, 27, 390–407.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marschall, H.; Forman, A.; Lunde, S.J.; Kesmodel, U.S.; Hansen, K.E.; Vase, L. Is laparoscopic excision for superficial peritoneal endometriosis helpful or harmful? Protocol for a double-blinded, randomised, placebo-controlled, three-armed surgical trial. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e062808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackenzie, S.C.; Stephen, J.; Williams, L.; Daniels, J.; Norrie, J.; Becker, C.M.; Byrne, D.; Cheong, Y.; Clark, T.J.; Cooper, K.G.; et al. Effectiveness of laparoscopic removal of isolated superficial peritoneal endometriosis for the management of chronic pelvic pain in women (ESPriT2): Protocol for a multi-centre randomised controlled trial. Trials 2023, 24, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, K.A.; Benton, A.S.; Deimling, T.A.; Kunselman, A.R.; Harkins, G.J. Surgical Excision Versus Ablation for Superficial Endometriosis-Associated Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2019, 26, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lessans, N.; Gilan, A.; Dick, A.; Bibar, N.; Saar, T.D.; Porat, S.; Dior, U.P. Ovarian reserve markers of women with superficial endometriosis. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2023, 165, 696–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellicer, A.; Albert, C.; Garrido, N.; Navarro, J.; Remohí, J.; Simón, C. The pathophysiology of endometriosis-associated infertility: Follicular environment and embryo quality. J. Reprod. Fertil. Suppl. 2000, 55, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bafort, C.; Beebeejaun, Y.; Tomassetti, C.; Bosteels, J.; Duffy, J.M. Laparoscopic surgery for endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 2020, CD011031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kho, R.M.; Andres, M.P.; Borrelli, G.M.; Neto, J.S.; Zanluchi, A.; Abrão, M.S. Surgical treatment of different types of endometriosis: Comparison of major society guidelines and preferred clinical algorithms. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2018, 51, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Alterio, M.N.; D’Ancona, G.; Raslan, M.; Tinelli, R.; Daniilidis, A.; Angioni, S. Management Challenges of Deep Infiltrating Endometriosis. Int. J. Fertil. Steril. 2021, 15, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunselman, G.A.J.; Vermeulen, N.; Becker, C.; Calhaz-Jorge, C.; D’Hooghe, T.; De Bie, B.; Heikinheimo, O.; Horne, A.W.; Kiesel, L.; Nap, A.; et al. ESHRE guideline: Management of women with endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 2014, 29, 400–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapron, C.; Marcellin, L.; Borghese, B.; Santulli, P. Rethinking mechanisms, diagnosis and management of endometriosis. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019, 15, 666–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petraglia, F.; Vannuccini, S.; Santulli, P.; Marcellin, L.; Chapron, C. An update for endometriosis management: A position statement. J. Endometr. Uterine Disord. 2024, 6, 100062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Working Group of ESGE, ESHRE, and WES; Keckstein, J.; Becker, C.M.; Canis, M.; Feki, A.; Grimbizis, G.F.; Hummelshoj, L.; Nisolle, M.; Roman, H.; Saridogan, E.; et al. Recommendations for the surgical treatment of endometriosis. Part 2: Deep endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. Open. 2020, 2020, hoaa002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vercellini, P.; Crosignani, P.G.; Somigliana, E.; Berlanda, N.; Barbara, G.; Fedele, L. Medical treatment for rectovaginal endometriosis: What is the evidence? Hum. Reprod. 2009, 24, 2504–2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casper, R.F. Progestin-only pills may be a better first-line treatment for endometriosis than combined estrogen-progestin contraceptive pills. Fertil. Steril. 2017, 107, 533–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, P.H.; Pereira, R.M.; Zanatta, A.; Alegretti, J.R.; Motta, E.L.; Serafini, P.C. Extensive excision of deep infiltrative endometriosis before in vitro fertilization significantly improves pregnancy rates. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2009, 16, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubod, C.; Fouquet, A.; Bartolo, S.; Lepage, J.; Capelle, A.; Lefebvre, C.; Kamus, E.; Dewailly, D.; Collinet, P. Factors associated with pregnancy after in vitro fertilization in infertile patients with posterior deep pelvic endometriosis: A retrospective study. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Hum. Reprod. 2019, 48, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muzii, L.; DI Tucci, C.; Galati, G.; Mattei, G.; Chinè, A.; Cascialli, G.; Palaia, I.; Panici, P.B. Endometriosis-associated infertility: Surgery or IVF? Minerva Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 73, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemos, N.; Souza, C.; Marques, R.M.; Kamergorodsky, G.; Schor, E.; Girão, M.J. Laparoscopic anatomy of the autonomic nerves of the pelvis and the concept of nerve-sparing surgery by direct visualization of autonomic nerve bundles. Fertil. Steril. 2015, 104, e11–e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ianieri, M.M.; Raimondo, D.; Rosati, A.; Cocchi, L.; Trozzi, R.; Maletta, M.; Raffone, A.; Campolo, F.; Beneduce, G.; Mollo, A.; et al. Impact of nerve-sparing posterolateral parametrial excision for deep infiltrating endometriosis on postoperative bowel, urinary, and sexual function. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2022, 159, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mabrouk, M.; Raimondo, D.; Altieri, M.; Arena, A.; Del Forno, S.; Moro, E.; Mattioli, G.; Iodice, R.; Seracchioli, R. Surgical, Clinical, and Functional Outcomes in Patients with Rectosigmoid Endometriosis in the Gray Zone: 13-Year Long-Term Follow-up. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2019, 26, 1110–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendifallah, S.; Puchar, A.; Vesale, E.; Moawad, G.; Daraï, E.; Roman, H. Surgical Outcomes after Colorectal Surgery for Endometriosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2021, 28, 453–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, H.; Huet, E.; Bridoux, V.; Khalil, H.; Hennetier, C.; Bubenheim, M.; Braund, S.; Tuech, J.-J. Long-term Outcomes Following Surgical Management of Rectal Endometriosis: Seven-year Follow-up of Patients Enrolled in a Randomized Trial. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2022, 29, 767–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Possover, M.; Quakernack, J.; Chiantera, V. The LANN technique to reduce postoperative functional morbidity in laparoscopic radical pelvic surgery. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2005, 201, 913–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roman, H.; Bubenheim, M.; Huet, E.; Bridoux, V.; Zacharopoulou, C.; Daraï, E.; Collinet, P.; Tuech, J.-J. Conservative surgery versus colorectal resection in deep endometriosis infiltrating the rectum: A randomized trial. Hum. Reprod. 2018, 33, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourdel, N.; Comptour, A.; Bouchet, P.; Gremeau, A.; Pouly, J.; Slim, K.; Pereira, B.; Canis, M. Long-term evaluation of painful symptoms and fertility after surgery for large rectovaginal endometriosis nodule: A retrospective study. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2018, 97, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donnez, J.; Squifflet, J. Complications, pregnancy and recurrence in a prospective series of 500 patients operated on by the shaving technique for deep rectovaginal endometriotic nodules. Hum. Reprod. 2010, 25, 1949–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudelist, G.; Aas-Eng, M.K.; Birsan, T.; Berger, F.; Sevelda, U.; Kirchner, L.; Salama, M.; Dauser, B. Pain and fertility outcomes of nerve-sparing, full-thickness disk or segmental bowel resection for deep infiltrating endometriosis—A prospective cohort study. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2018, 97, 1438–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudelist, G.; Pashkunova, D.; Darici, E.; Rath, A.; Mitrowitz, J.; Dauser, B.; Senft, B.; Bokor, A. Pain, gastrointestinal function and fertility outcomes of modified nerve-vessel sparing segmental and full thickness discoid resection for deep colorectal endometriosis—A prospective cohort study. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2023, 102, 1347–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stepniewska, A.; Pomini, P.; Scioscia, M.; Mereu, L.; Ruffo, G.; Minelli, L. Fertility and clinical outcome after bowel resection in infertile women with endometriosis. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2010, 20, 602–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bendifallah, S.; Roman, H.; D’Argent, E.M.; Touleimat, S.; Cohen, J.; Darai, E.; Ballester, M. Colorectal endometriosis-associated infertility: Should surgery precede ART? Fertil. Steril. 2017, 108, 525–531.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barra, F.; Scala, C.; Biscaldi, E.; Vellone, V.G.; Ceccaroni, M.; Terrone, C.; Ferrero, S. Ureteral endometriosis: A systematic review of epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment, risk of malignant transformation and fertility. Hum. Reprod. Update 2018, 24, 710–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somigliana, E.; Vercellini, P.; Gattei, U.; Chopin, N.; Chiodo, I.; Chapron, C. Bladder endometriosis: Getting closer and closer to the unifying metastatic hypothesis. Fertil. Steril. 2007, 87, 1287–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saavalainen, L.; Heikinheimo, O.; Tiitinen, A.; Härkki, P. Deep infiltrating endometriosis affecting the urinary tract—Surgical treatment and fertility outcomes in 2004–2013. Gynecol. Surg. 2016, 13, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timoh, K.N.; Ballester, M.; Bendifallah, S.; Fauconnier, A.; Darai, E. Fertility outcomes after laparoscopic partial bladder resection for deep endometriosis: Retrospective analysis from two expert centres and review of the literature. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2018, 220, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bird, C.C.; McElin, T.W.; Manalo-Estrella, P. The elusive adenomyosis of the uterus—Revisited. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1972, 112, 583–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E Bulun, S.; Yildiz, S.; Adli, M.; Wei, J.-J. Adenomyosis pathogenesis: Insights from next-generation sequencing. Hum. Reprod. Update 2021, 27, 1086–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Solares, J.; Donnez, J.; Donnez, O.; Dolmans, M.M. Pathogenesis of uterine adenomyosis: Invagination or metaplasia? Fertil. Steril. 2018, 109, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, X.; Guo, S. Clinical profiles of 710 premenopausal women with adenomyosis who underwent hysterectomy. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2014, 40, 485–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Bosch, T.; Duehom, M.; Leone, F.P.G.; Valentin, L.; Rasmussen, C.K.; Votino, A.; Van Schoubroeck, D.; Landolfo, C.; Installé, A.J.F.; Guerriero, S.; et al. Terms, definitions and measurements to describe sonographic features of myometrium and uterine masses: A consensus opinion from the Morphological Uterus Sonographic Assessment (MUSA) group. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 46, 284–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Exacoustos, C.; Morosetti, G.; Conway, F.; Camilli, S.; Martire, F.G.; Lazzeri, L.; Piccione, E.; Zupi, E. New sonographic classification of adenomyosis: Do type and degree of adenomyosis correlate to severity of symptoms? J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2019, 27, 1308–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdon, M.; Oliveira, J.; Marcellin, L.; Santulli, P.; Bordonne, C.; Mantelet, L.M.; E Millischer, A.; Bureau, G.P.; Chapron, C. Adenomyosis of the inner and outer myometrium are associated with different clinical profiles. Hum. Reprod. 2021, 36, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vercellini, P.; Viganò, P.; Bandini, V.; Buggio, L.; Berlanda, N.; Somigliana, E. Association of endometriosis and adenomyosis with pregnancy and infertility. Fertil. Steril. 2023, 119, 727–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etrusco, A.; Barra, F.; Chiantera, V.; Ferrero, S.; Bogliolo, S.; Evangelisti, G.; Oral, E.; Pastore, M.; Izzotti, A.; Venezia, R.; et al. Current Medical Therapy for Adenomyosis: From Bench to Bedside. Drugs 2023, 83, 1595–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cope, A.G.; Ainsworth, A.J.; Stewart, E.A. Current and future medical therapies for adenomyosis. Semin. Reprod. Med. 2020, 38, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otsubo, Y.; Nishida, M.; Arai, Y.; Ichikawa, R.; Taneichi, A.; Sakanaka, M. Association of uterine wall thickness with pregnancy outcome following uterine-sparing surgery for diffuse uterine adenomyosis. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2016, 56, 88–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwack, J.-Y.; Lee, S.-J.; Kwon, Y.-S. Pregnancy and delivery outcomes in the women who have received adenomyomectomy: Performed by a single surgeon by a uniform surgical technique. Taiwan. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 60, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mettler, L. Adenomyosis and Endometriosis Surgical Treatment. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2008, 15, 19S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelage, J.-P.; Jacob, D.; Fazel, A.; Namur, J.; Laurent, A.; Rymer, R.; Le Dref, O. Midterm results of uterine artery embolization for symptomatic adenomyosis: Initial experience. Radiology 2005, 234, 948–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Bruijn, A.M.; Smink, M.; Hehenkamp, W.J.K.; Nijenhuis, R.J.; Smeets, A.J.; Boekkooi, F.; Reuwer, P.J.H.M.; Van Rooij, W.J.; Lohle, P.N.M. Uterine Artery Embolization for Symptomatic Adenomyosis: 7-Year Clinical Follow-up Using UFS-Qol Questionnaire. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 2017, 40, 1344–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Zhai, T.; Sun, X.; Du, X.; Zhang, X.; Shi, X.; Shu, Y.; Yan, X.; Xia, Q.; Ma, Y. Efficacy and safety of acupuncture for adenomyosis. Medicine 2021, 100, e28080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golfier, F.; Chanavaz-Lacheray, I.; Descamps, P.; Agostini, A.; Poilblanc, M.; Rousset, P.; Bolze, P.-A.; Panel, P.; Collinet, P.; Hebert, T.; et al. The definition of Endometriosis Expert Centres. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Hum. Reprod. 2018, 47, 179–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ottolina, J.; Villanacci, R.; D’Alessandro, S.; He, X.; Grisafi, G.; Ferrari, S.M.; Candiani, M. Endometriosis and Adenomyosis: Modern Concepts of Their Clinical Outcomes, Treatment, and Management. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3996. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13143996

Ottolina J, Villanacci R, D’Alessandro S, He X, Grisafi G, Ferrari SM, Candiani M. Endometriosis and Adenomyosis: Modern Concepts of Their Clinical Outcomes, Treatment, and Management. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(14):3996. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13143996

Chicago/Turabian StyleOttolina, Jessica, Roberta Villanacci, Sara D’Alessandro, Xuemin He, Giorgia Grisafi, Stefano Maria Ferrari, and Massimo Candiani. 2024. "Endometriosis and Adenomyosis: Modern Concepts of Their Clinical Outcomes, Treatment, and Management" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 14: 3996. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13143996

APA StyleOttolina, J., Villanacci, R., D’Alessandro, S., He, X., Grisafi, G., Ferrari, S. M., & Candiani, M. (2024). Endometriosis and Adenomyosis: Modern Concepts of Their Clinical Outcomes, Treatment, and Management. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(14), 3996. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13143996