Self-Management among Stroke Survivors in the United States, 2016 to 2021

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Variable Definitions

2.4. Outcome Measures

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics of the Studied Population

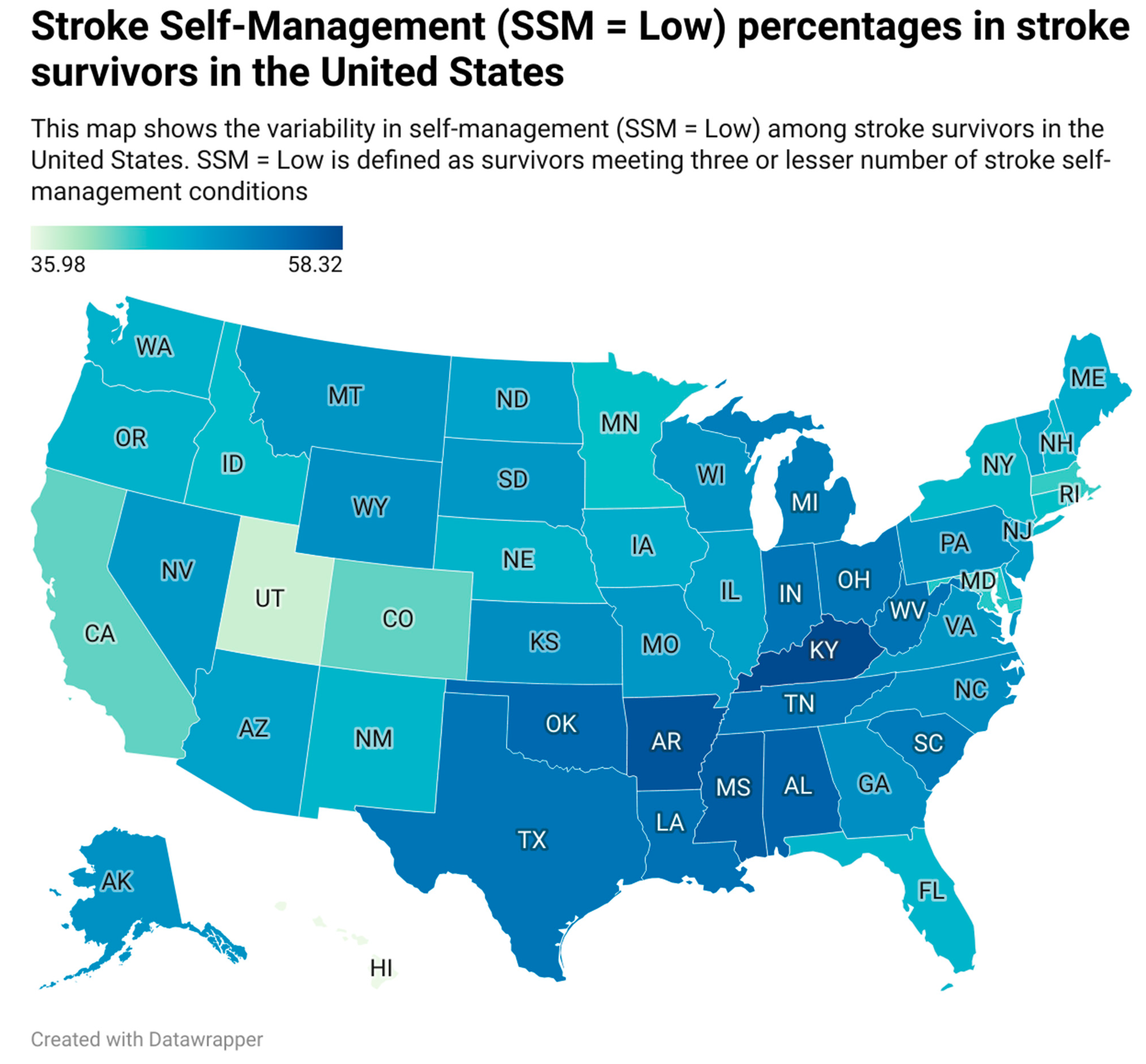

3.2. Prevalence of Self-Management among Stroke Survivors in the United States

3.3. Association of Sociographic and Demographic Factors with SSM and Each of the Self-Management Conditions

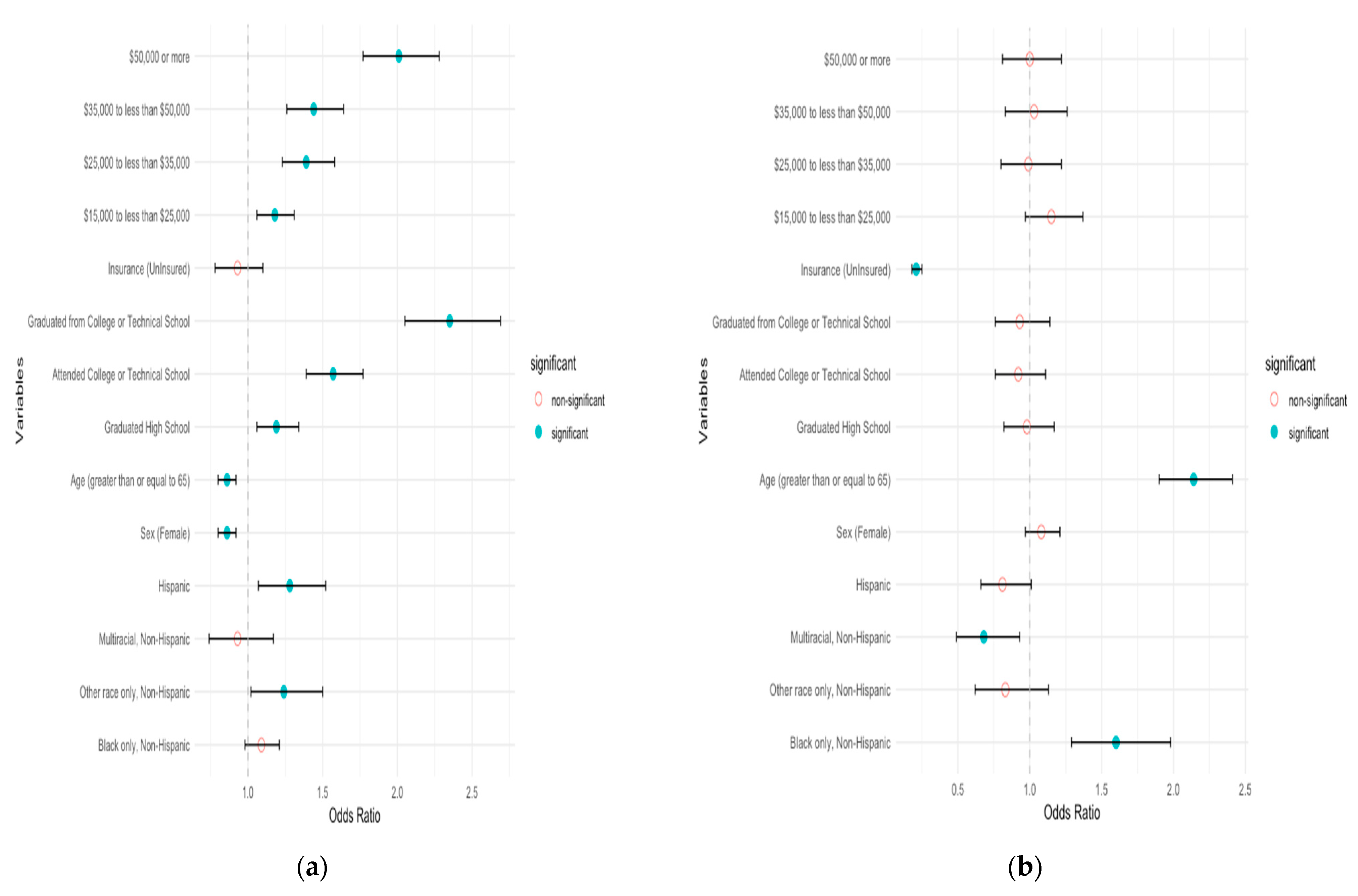

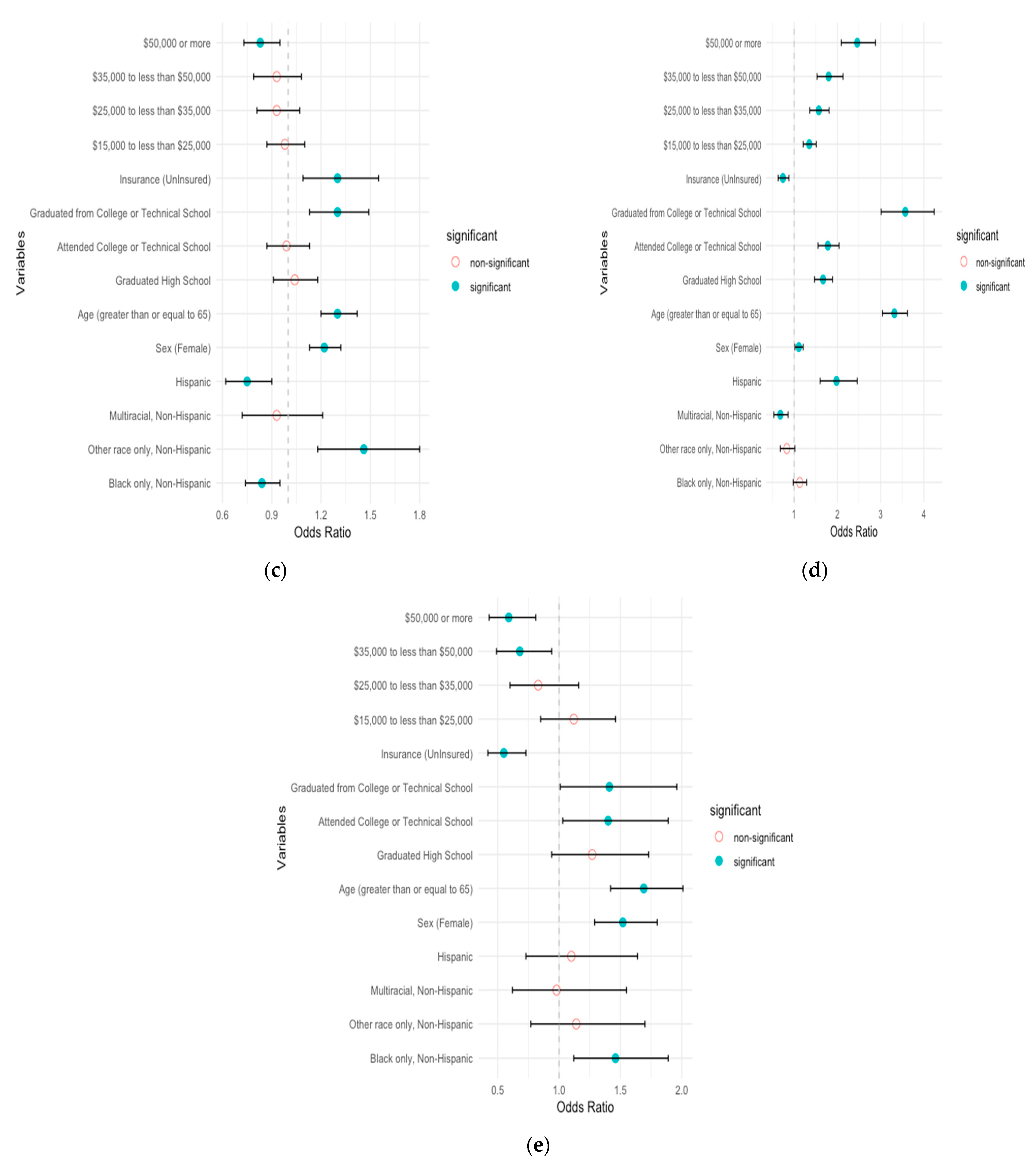

3.4. Prevalence of Self-Management Geographically

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Writing Group Members; Lloyd-Jones, D.; Adams, R.; Carnethon, M.; De Simone, G.; Ferguson, T.B.; Flegal, K.; Ford, E.; Furie, K.; Go, A.; et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2009 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation 2009, 119, e21–e181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riegel, B.; Moser, D.K.; Buck, H.G.; Dickson, V.V.; Dunbar, S.B.; Lee, C.S.; Lennie, T.A.; Lindenfeld, J.; Mitchell, J.E.; Treat-Jacobson, D.J.; et al. Self-Care for the Prevention and Management of Cardiovascular Disease and Stroke: A Scientific Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2017, 6, e006997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouyang, W.; Chen, H.; Xu, X.; Zhang, X.; Fu, L.; Tang, F.; Wen, Z.; Marrone, G.; Liu, L.; Lin, J.; et al. Self-Management Program for Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease (SMP-CKD) in Southern China: Protocol for an Ambispective Cohort Study. BMC Nephrol. 2022, 23, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakakibara, B.M.; Kim, A.J.; Eng, J.J. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis on Self-Management for Improving Risk Factor Control in Stroke Patients. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2017, 24, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, R.R.; Phad, A.; McGrath, R.; Haire-Joshu, D. Prevalence of Five Lifestyle Risk Factors among U.S. Adults With and Without Stroke. Disabil. Health J. 2019, 12, 323–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, R.R.; Phad, A.; McGrath, R.; Tabak, R.; Haire-Joshu, D. Prevalence of 3 Healthy Lifestyle Behaviors Among US Adults With and Without History of Stroke. Prev. Chronic. Dis. 2019, 16, E23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wali, H.; Kurdi, S.; Bilal, J.; Riaz, I.; Bhattacharjee, S. Health Behaviors Among Stroke Survivors In The United States: A Propensity Score Matched Study. Value Health 2018, 21, S57–S58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, A. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2002, 94, 666–668. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cruz-Flores, S.; Rabinstein, A.; Biller, J.; Elkind, M.S.V.; Griffith, P.; Gorelick, P.B.; Howard, G.; Leira, E.C.; Morgenstern, L.B.; Ovbiagele, B.; et al. Racial-Ethnic Disparities in Stroke Care: The American Experience: A Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2011, 42, 2091–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Huynh, M.N.; Young, J.D.; Alexeeff, S.; Hatfield, M.K.; Sidney, S. Shake Rattle & Roll–Design and Rationale for a Pragmatic Trial to Improve Blood Pressure Control among Blacks with Persistent Hypertension. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2019, 76, 85–92. [Google Scholar]

- Huynh, M.N.N.; Young, J.D.; Hatfield, M.; Alexeeff, S.; Chinn, T.; Sorel, M.; Sidney, S. Longer Term Effect of Lifestyle Intervention on Blood Pressure Control Among African Americans: One Year Follow-up of Shake, Rattle & Roll Trial. Stroke 2018, 49, A186. [Google Scholar]

- Victor, R.G.; Lynch, K.; Li, N.; Blyler, C.; Muhammad, E.; Handler, J.; Brettler, J.; Rashid, M.; Hsu, B.; Foxx-Drew, D.; et al. A Cluster-Randomized Trial of Blood-Pressure Reduction in Black Barbershops. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 1291–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Victor, R.G.; Blyler, C.A.; Li, N.; Lynch, K.; Moy, N.B.; Rashid, M.; Chang, L.C.; Handler, J.; Brettler, J.; Rader, F.; et al. Sustainability of Blood Pressure Reduction in Black Barbershops. Circulation 2019, 139, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogedegbe, G.O. Comparative Effectiveness of Home Bp Telemonitoring plus Nurse Case Management (Hbptm+ Ncm) versus Hbptm Alone on Systolic Bp (Sbp) Reduction among Minority Stroke Survivors. In Proceedings of the International Stroke Conference, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 18–21 February 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Boden-Albala, B.; Goldmann, E.; Parikh, N.S.; Carman, H.; Roberts, E.T.; Lord, A.S.; Torrico, V.; Appleton, N.; Birkemeier, J.; Parides, M.; et al. Efficacy of a Discharge Educational Strategy vs Standard Discharge Care on Reduction of Vascular Risk in Patients With Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack. JAMA Neurol. 2019, 76, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.L.; Conley, K.M.; Sánchez, B.N.; Resnicow, K.; Cowdery, J.E.; Sais, E.; Murphy, J.; Skolarus, L.E.; Lisabeth, L.D.; Morgenstern, L.B. A Multicomponent Behavioral Intervention to Reduce Stroke Risk Factor Behaviors: The Stroke Health and Risk Education Cluster-Randomized Controlled Trial. Stroke 2015, 46, 2861–2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, N.-Y.; Lin, Y.-H.; Chen, H.-M. Continuity of Care and Self-Management among Patients with Stroke: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare 2021, 9, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Data; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2016.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Data; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2017.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Data; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2018.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Data; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2019.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Data; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2021.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Data; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2020.

- Von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for Reporting Observational Studies. Lancet 2007, 370, 1453–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierannunzi, C.; Hu, S.S.; Balluz, L. A Systematic Review of Publications Assessing Reliability and Validity of the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), 2004–2011. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okura, Y.; Urban, L.H.; Mahoney, D.W.; Jacobsen, S.J.; Rodeheffer, R.J. Agreement between Self-Report Questionnaires and Medical Record Data Was Substantial for Diabetes, Hypertension, Myocardial Infarction and Stroke but Not for Heart Failure. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2004, 57, 1096–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleindorfer, D.O.; Towfighi, A.; Chaturvedi, S.; Cockroft, K.M.; Gutierrez, J.; Lombardi-Hill, D.; Kamel, H.; Kernan, W.N.; Kittner, S.J.; Leira, E.C.; et al. 2021 Guideline for the Prevention of Stroke in Patients with Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack: A Guideline From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2021, 52, e364–e467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, D.K.; Denny, C.H.; Keenan, N.L.; Croft, J.B.; Sundaram, A.A.; Greenlund, K.J. Racial/Ethnic and Socioeconomic Differences in Multiple Risk Factors for Heart Disease and Stroke in Women: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2003. J. Women’s Health 2006, 15, 1000–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fini, N.A.; Holland, A.E.; Keating, J.; Simek, J.; Bernhardt, J. How Physically Active Are People Following Stroke? Systematic Review and Quantitative Synthesis. Phys. Ther. 2017, 97, 707–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turan, T.N.; Nizam, A.; Lynn, M.J.; Egan, B.M.; Le, N.-A.; Lopes-Virella, M.F.; Hermayer, K.L.; Harrell, J.; Derdeyn, C.P.; Fiorella, D.; et al. Relationship between Risk Factor Control and Vascular Events in the SAMMPRIS Trial. Neurology 2017, 88, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, E.; Catalano, T.; Kuipers, P.; Posner, N.; Buys, N.; Charker, J. Recovery Following Stroke: The Role of Self-Management Education. Soc. Sci. Med. 2007, 64, 735–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warner, G.; Packer, T.; Villeneuve, M.; Audulv, A.; Versnel, J. A Systematic Review of the Effectiveness of Stroke Self-Management Programs for Improving Function and Participation Outcomes: Self-Management Programs for Stroke Survivors. Disabil. Rehabil. 2015, 37, 2141–2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huijbregts, M.P.; Myers, A.M.; Streiner, D.; Teasell, R. Implementation, Process, and Preliminary Outcome Evaluation of Two Community Programs for Persons with Stroke and Their Care Partners. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 2008, 15, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadilhac, D.A.; Hoffmann, S.; Kilkenny, M.; Lindley, R.; Lalor, E.; Osborne, R.H.; Batterbsy, M. A Phase II Multicentered, Single-Blind, Randomized, Controlled Trial of the Stroke Self-Management Program. Stroke 2011, 42, 1673–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, S.; Zhu, B.-P.; Black, W.; Brownson, R. A Comparison of National Estimates of Obesity Prevalence from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System and the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Int. J. Obes. 2006, 30, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capriotti, T.; Murphy, T. Ischemic Stroke. Home Healthc. Now 2016, 34, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factor | Whole Population (Weighted) % |

|---|---|

| Respondents, raw unweighted frequency | 95,645 |

| Race | |

| White only, non-Hispanic | 66.4 |

| Black only, non-Hispanic | 16.4 |

| Other races only, non-Hispanic | 4.6 |

| Multiracial, non-Hispanic | 1.8 |

| Hispanic | 10.6 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 48.8 |

| Female | 51.1 |

| Age | |

| 18 to 64 | 48.7 |

| 65 or older | 51.2 |

| Education | |

| Did not graduate high school | 21.6 |

| Graduated high school | 30.9 |

| Attended college or technical school | 30.8 |

| Graduated from college or technical school | 16.6 |

| Lacking health insurance | 7.0 |

| Rural residence | 22.9 |

| Stroke Belt residence | 26.3 |

| Income | |

| Less than $15,000 | 20.5 |

| $15,000 to less than $25,000 | 25.7 |

| $25,000 to less than $35,000 | 12.9 |

| $35,000 to less than $50,000 | 13.1 |

| $50,000 or more | 27.6 |

| Factor | N (Unweighted) | Low SSM Percentage (95% CI) (Weighted) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | p < 0.0001 | ||

| 18 to 64 years old | 35,125 | 56.8 (55.7–57.9) | |

| 65 or older | 59,865 | 42.3 (41.4–43.2) | |

| Sex | p = 0.6 | ||

| Male | 43,445 | 49.2 (48.1–50.2) | |

| Female | 52,170 | 49.5 (48.5–50.5) | |

| Race and ethnicity | p < 0.0001 | ||

| White only, non-Hispanic | 71,880 | 48.6 (47.8–49.4) | |

| Black only, non-Hispanic | 10,351 | 52.0 (50.0–53.9) | |

| Other races only, non-Hispanic | 4467 | 43.4 (39.1–47.6) | |

| Multiracial, non-Hispanic | 2506 | 53.3 (48.6–58.0) | |

| Hispanic | 4610 | 52.0 (48.7–55.4) | |

| Health insurance | p < 0.0001 | ||

| Insured | 76,730 | 47.8 (47.0–48.7) | |

| Uninsured | 3892 | 69.6 (66.4–72.9) | |

| Stroke Belt | p < 0.0001 | ||

| Stroke Belt residents | 21,334 | 53.1 (52.1–54.2) | |

| Non-Stroke Belt residents | 74,311 | 48.0 (47.1–48.9) | |

| Rurality | p < 0.05 | ||

| Nonrural | 17,519 | 49.1 (48.3–49.9) | |

| Rural | 30,787 | 52.2 (50.2–54.1) | |

| Education | p < 0.0001 | ||

| Did not graduate high school | 11,779 | 60.9 (59.0–62.7) | |

| Graduated high school | 30,978 | 53.0 (51.8–54.2) | |

| Attended college or technical school | 28,237 | 46.8 (45.5–48.1) | |

| Graduated from college or technical school | 24,423 | 32.5 (31.2–33.8) | |

| Income | p < 0.0001 | ||

| Less than $15,000 | 15,223 | 62.5 (60.7–64.3) | |

| $15,000 to less than $25,000 | 20,169 | 54.1 (52.5–55.6) | |

| $25,000 to less than $35,000 | 10,808 | 49.5 (47.4–51.6) | |

| $35,000 to less than $50,000 | 10,827 | 45.1 (42.9–47.3) | |

| $50,000 or more | 22,005 | 39.1 (37.6–40.6) |

| Variables (Reference) | Odds Ratio Unadjusted (95% CI) | p-Value | Odds Ratio Adjusted (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race | - | - | - | - |

| White (reference) | ||||

| Black only, non-Hispanic | 0.87 (0.8–0.95) | 0.0016 | 1.04 (0.92–1.17) | 0.5546 |

| Other races only, non-Hispanic (comes at the end) | 1.23 (1.04–1.47) | 0.0187 | 1.27 (1.01–1.59) | 0.0414 |

| Multiracial, non-Hispanic | 0.83 (0.68–1) | 0.0556 | 0.9 (0.72–1.13) | 0.3788 |

| Hispanic | 0.87 (0.76–1) | 0.0468 | 1.2 (0.99–1.45) | 0.0689 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male (reference) | - | - | - | - |

| Female | 0.98 (0.93–1.04) | 0.6071 | 1.07 (0.99–1.16) | 0.092 |

| Age | ||||

| Less than 65 (reference) | - | - | - | - |

| 65 and above | 1.8 (1.69–1.91) | <0.0001 | 1.70 (1.56–1.86) | <0.0001 |

| Education | ||||

| Did not graduate high school (reference) | - | - | - | - |

| Graduated high school | 1.38 (1.26–1.51) | <0.0001 | 1.31 (1.15–1.49) | <0.0001 |

| Attended college or technical school | 1.77 (1.61–1.94) | <0.0001 | 1.71 (1.5–1.94) | <0.0001 |

| Graduated from college or technical school | 3.23 (2.93–3.57) | <0.0001 | 2.49 (2.16–2.88) | <0.0001 |

| Insurance | ||||

| Insured (reference) | - | - | - | - |

| Uninsured | 0.4 (0.34–0.47) | <0.0001 | 0.46 (0.38–0.56) | <0.0001 |

| Income | ||||

| Less than $15,000 (reference) | - | - | - | - |

| $15,000 to less than $25,000 | 1.41 (1.28–1.56) | <0.0001 | 1.14 (1.01–1.28) | <0.05 |

| $25,000 to less than $35,000 | 1.7 (1.52–1.9) | <0.0001 | 1.21 (1.05–1.4) | <0.05 |

| $35,000 to less than $50,000 | 2.03 (1.8–2.28) | <0.0001 | 1.3 (1.13–1.51) | <0.0001 |

| $50,000 or more | 2.6 (2.35–2.87) | <0.0001 | 1.45 (1.26–1.67) | <0.0001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vemuri, A.K.; Hejazian, S.S.; Vafaei Sadr, A.; Zhou, S.; Decker, K.; Hakun, J.; Abedi, V.; Zand, R. Self-Management among Stroke Survivors in the United States, 2016 to 2021. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4338. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13154338

Vemuri AK, Hejazian SS, Vafaei Sadr A, Zhou S, Decker K, Hakun J, Abedi V, Zand R. Self-Management among Stroke Survivors in the United States, 2016 to 2021. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(15):4338. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13154338

Chicago/Turabian StyleVemuri, Ajith Kumar, Seyyed Sina Hejazian, Alireza Vafaei Sadr, Shouhao Zhou, Keith Decker, Jonathan Hakun, Vida Abedi, and Ramin Zand. 2024. "Self-Management among Stroke Survivors in the United States, 2016 to 2021" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 15: 4338. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13154338

APA StyleVemuri, A. K., Hejazian, S. S., Vafaei Sadr, A., Zhou, S., Decker, K., Hakun, J., Abedi, V., & Zand, R. (2024). Self-Management among Stroke Survivors in the United States, 2016 to 2021. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(15), 4338. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13154338