How the Mode of Delivery Is Influenced by Patient’s Opinions and Risk-Informed Consent in Women with a History of Caesarean Section? Is Vaginal Delivery a Real Option after Caesarean Section?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

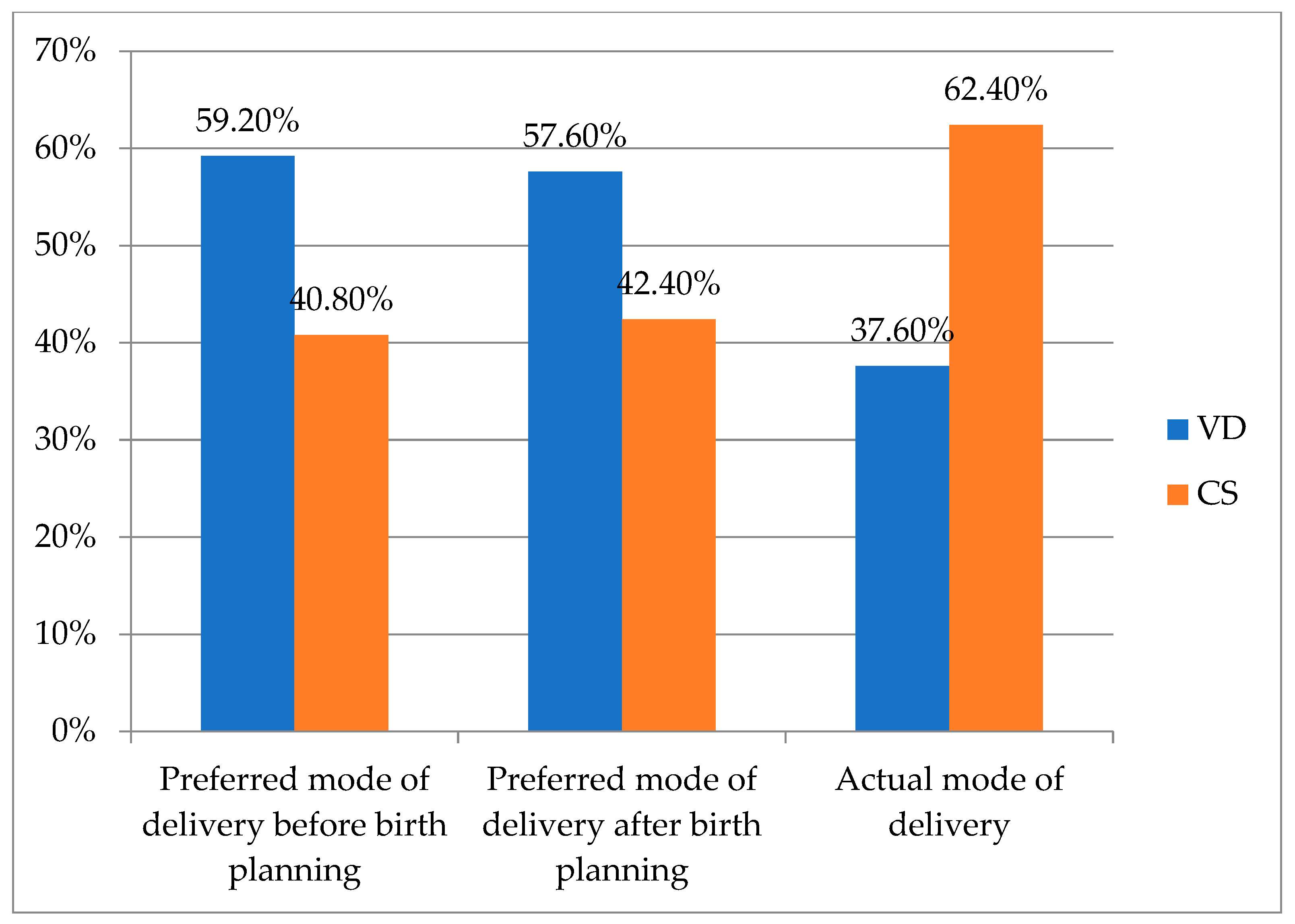

3.1. Questionnaire Response Analysis

3.2. Actual Mode of Delivery

3.3. CS Indications: Past and Present

3.4. Challenges and Complications of VD

3.5. Neonatal Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ayachi, A.; Derouich, S.; Morjene, I.; Mkaouer, L.; Mnaser, D.; Mourali, M. Facteurs prédictifs de l’issue de l’accouchement sur utérus unicicatriciel, expérience du centre de Maternité de Bizerte [Predictors of birth outcomes related to women with a previous caesarean section: Experience of a Motherhood Center, Bizerte]. Pan. Afr. Med. J. 2016, 25, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cobec, I.M.; Varzaru, V.B.; Kövendy, T.; Kuban, L.; Eftenoiu, A.E.; Moatar, A.E.; Rempen, A. External Cephalic Version—A Chance for Vaginal Delivery at Breech Presentation. Medicina 2022, 58, 1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, H.; Luo, S.; Gu, W. Oxytocin use in trial of labour after cesarean and its relationship with risk of uterine rupture in women with one previous cesarean section: A meta-analysis of observational studies. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021, 21, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, M.; Roy, A.; Grobman, W.A.; Miller, E.S. Association Between Attempted External Cephalic Version and Perinatal Morbidity and Mortality. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 132, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Sha, S.; Xu, S.; Zhan, B.; Guan, X.; Ling, F. Analysis of Maternal and Infant Outcomes and Related Factors of Vaginal Delivery of Second Pregnancy after Cesarean Section. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2022, 2022, 4243174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtin, S.C.; Gregory, K.D.; Korst, L.M.; Uddin, S.F.G. Maternal morbidity for vaginal and cesarean deliveries, according to previous cesarean history: New data from the birth certificate, 2013. Natl. Cent. Health Stat. Natl. Vital. Stat. Rep. 2015, 64, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, M.G.; Reed, K.L. External Cephalic Version in Cases of Imminent Delivery at Preterm Gestational Ages: A Prospective Series. AJP Rep. 2019, 9, e384–e388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Memon, H.; Handa, V.L. Pelvic floor disorders following vaginal or cesarean delivery. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012, 24, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, C.; de Mooij, Y.M.; Blomaard, C.M.; Derks, J.B.; van Leeuwen, E.; Limpens, J.; Schuit, E.; Mol, B.W.; Pajkrt, E. Vaginal delivery in women with a low-lying placenta: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG 2019, 126, 1118–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobec, I.M.; Rempen, A. Couvelaire-Uterus: Literature review and case report. Rom. J. Mil. Med. 2021, 124, 244–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Song, X.; Ding, H.; Shen, X.; Shen, R.; Hu, L.Q.; Long, W. Prediction of vaginal birth after cesarean delivery in Chinese parturients. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sentilhes, L.; Vayssière, C.; Beucher, G.; Deneux-Tharaux, C.; Deruelle, P.; Diemunsch, P.; Gallot, D.; Haumonté, J.B.; Heimann, S.; Kayem, G.; et al. Delivery for women with a previous cesarean: Guidelines for clinical practice from the French College of Gynecologists and Obstetricians (CNGOF). Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2013, 170, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colais, P.; Bontempi, K.; Pinnarelli, L.; Piscicelli, C.; Mappa, I.; Fusco, D.; Davoli, M. Vaginal birth after caesarean birth in Italy: Variations among areas of residence and hospitals. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018, 18, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cobec, I.M.; Seropian, P.; Rempen, A. Pregnancy in a non-communicating rudimentary horn of a unicornuate uterus. Hippokratia 2019, 23, 92–94. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- German Society for Obstetrics and Gynecology (DGGG) Board for Prenatal Medicine and Obstetrics. Board for Materno-Fetal Medicine (AGMFM) The Caesarean Section. AWMF-Registernummer 015-084 (S3). Available online: https://www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/015-084l_S3_Sectio-caesarea_2020-06_1_02.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Lundgren, I.; Smith, V.; Nilsson, C.; Vehvilainen-Julkunen, K.; Nicoletti, J.; Devane, D.; Bernloehr, A.; van Limbeek, E.; Lalor, J.; Begley, C. Clinician-centred interventions to increase vaginal birth after caesarean section (VBAC): A systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015, 15, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, C.; Lundgren, I.; Smith, V.; Vehvilainen-Julkunen, K.; Nicoletti, J.; Devane, D.; Bernloehr, A.; van Limbeek, E.; Lalor, J.; Begley, C. Women-centred interventions to increase vaginal birth after caesarean section (VBAC): A systematic review. Midwifery 2015, 31, 657–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betrán, A.P.; Temmerman, M.; Kingdon, C.; Mohiddin, A.; Opiyo, N.; Torloni, M.R.; Zhang, J.; Musana, O.; Wanyonyi, S.Z.; Gülmezoglu, A.M.; et al. Interventions to reduce unnecessary caesarean sections in healthy women and babies. Lancet 2018, 392, 1358–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, I.; Opiyo, N.; Tavender, E.; Mortazhejri, S.; Rader, T.; Petkovic, J.; Yogasingam, S.; Taljaard, M.; Agarwal, S.; Laopaiboon, M.; et al. Non-clinical interventions for reducing unnecessary caesarean section. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 9, CD005528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, V.; Gallagher, L.; Carroll, M.; Hannon, K.; Begley, C. Antenatal and intrapartum interventions for reducing caesarean section, promoting vaginal birth, and reducing fear of childbirth: An overview of systematic reviews. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0224313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, V.; Hannon, K.; Begley, C. Clinician’s attitudes towards caesarean section: A cross-sectional survey in two tertiary level maternity units in Ireland. Women Birth 2022, 35, 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzoni, A.; Althabe, F.; Liu, N.H.; Bonotti, A.M.; Gibbons, L.; Sánchez, A.J.; Belizán, J.M. Women’s preference for caesarean section: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BJOG 2011, 118, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuglenes, D.; Oian, P.; Kristiansen, I.S. Obstetricians’ choice of cesarean delivery in ambiguous cases: Is it influenced by risk attitude or fear of complaints and litigation? Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009, 200, 48.e1–48.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zwecker, P.; Azoulay, L.; Abenhaim, H.A. Effect of fear of litigation on obstetric care: A nationwide analysis on obstetric practice. Am. J. Perinatol. 2011, 28, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, S.; Begley, C.; Daly, D. Influence of women’s request and preference on the rising rate of caesarean section—A comparison of reviews. Midwifery 2020, 88, 102765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kornelsen, J.; Hutton, E.; Munro, S. Influences on decision making among primiparous women choosing elective caesarean section in the absence of medical indications: Findings from a qualitative investigation. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2010, 32, 962–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, H.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, N.; Chongsuvivatwong, V.; Wang, Q.; Gong, J.; Sriplung, H. Women’s cesarean section preferences and influencing factors in relation to China’s two-child policy: A cross-sectional study. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2018, 12, 2093–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Li, Y.; Sanchez-Barricarte, J.J. Fertility Intention, Son Preference, and Second Childbirth: Survey Findings from Shaanxi Province of China. Soc. Indic. Res. 2016, 125, 935–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paré, E.; Quiñones, J.N.; Macones, G.A. Vaginal birth after caesarean section versus elective repeat caesarean section: Assessment of maternal downstream health outcomes. BJOG 2006, 113, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, G.A.; Nicholson, S.M.; Morrison, J.J. Vaginal birth after caesarean section: Current status and where to from here? Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2018, 224, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolmacheva, L. Vaginal birth after caesarean or elective caesarean—What factors influence women’s decisions? Br. J. Midwifery 2015, 23, 470–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, K.E.; Kurinczuk, J.J.; Alfirevic, Z.; Spark, P.; Brocklehurst, P.; Knight, M. Uterine rupture by intended mode of delivery in the UK: A national case-control study. PLoS Med. 2012, 9, e1001184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silver, R.M.; Landon, M.B.; Rouse, D.J.; Leveno, K.J.; Spong, C.Y.; Thom, E.A.; Moawad, A.H.; Caritis, S.N.; Harper, M.; Wapner, R.J.; et al. Maternal morbidity associated with multiple repeat cesarean deliveries. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006, 107, 1226–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guise, J.M.; Denman, M.A.; Emeis, C.; Marshall, N.; Walker, M.; Fu, R.; Janik, R.; Nygren, P.; Eden, K.B.; McDonagh, M. Vaginal birth after cesarean: New insights on maternal and neonatal outcomes. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 115, 1267–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emmett, C.L.; Montgomery, A.A.; Murphy, D.J.; DiAMOND Study Group. Preferences for mode of delivery after previous caesarean section: What do women want, what do they get and how do they value outcomes? Health Expect. 2011, 14, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Antoine, C.; Young, B.K. Cesarean section one hundred years 1920–2020: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. J. Perinat. Med. 2020, 49, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.T.; Hsieh, Y.C.; Shen, H.; Cheng, C.H.; Lee, K.H.; Torng, P.L. Vaginal birth after cesarean section: Experience from a regional hospital. Taiwan J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 61, 422–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidelines Programm of the German/Austrian/Swiss Society for Obstetrics and Gynecology (DGGG/OEGGG/SGGG). Induction of Labour. AWMF-Registernummer 015-088 (S2k). Available online: https://register.awmf.org/assets/guidelines/015-088ladd_S2k_Geburtseinleitung_2021-04.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Darmian, M.E.; Yousefzadeh, S.; Najafi, T.F.; Javadi, S.V. Comparative study of teaching natural delivery benefits and optimism training on mothers’ attitude and intention to select a type of delivery: An educational experiment. Electron. Physician 2018, 10, 7038–7045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Preferred Mode of Delivery after Birth Planning | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VD | CS | |||

| Preferred mode of delivery before birth planning | VD | 72 | 2 | 74 |

| CS | 0 | 51 | 51 | |

| Total | 72 | 53 | 125 | |

| Preferred Mode of Delivery after Birth Planning | Actual Mode of Delivery | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VD | CS | ||||

| Natural | Vacuum Extraction | Planned CS | CS Performed during Labour by Medical Necessity | ||

| VD | 40 | 5 | 7 | 20 | 72 |

| CS | 2 | 0 | 43 | 8 | 53 |

| Total | 42 | 5 | 50 | 28 | 125 |

| Indication for Current CS | Planned CS | CS Performed during Labour by Medical Necessity | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| At the request of the patient with a history of CS | 44 | 10 | 54 |

| Pathological CTG | 0 | 7 | 7 |

| Stalled active labour phase | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| Stalled early labour phase | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Macrosomia | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Breech presentation | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Occiput posterior position | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Intra-amniotic infection | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Unsuccessful labour induction | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Inguinal pain | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Suspicion of uterine rupture | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| History of myoma enucleation | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Epilepsy | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 50 | 28 | 78 |

| Indication for the Actual Mode of Delivery in CS Patients Who Preferred CS | Planned CS | CS Performed during Labour by Medical Necessity | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| At the request of the patient with a history of CS | 38 | 7 | 45 |

| Breech presentation | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Macrosomia | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Inguinal pain | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| History of myoma enucleation | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Epilepsy | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 43 | 8 | 51 |

| Indication for Actual Mode of Delivery in CS Patients Who Preferred VD | Planned CS | CS Performed during Labour by Medical Necessity | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| At the request of the patient with a history of CS | 6 | 3 | 9 |

| Pathological CTG | 0 | 7 | 7 |

| Stalled active labour phase | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| Stalled early labour phase | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Occiput posterior position | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Intra-amniotic infection | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Macrosomia | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Unsuccessful labour induction | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Suspicion of uterine rupture | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 7 | 20 | 27 |

| Indication for Current CS Performed due to Medical Necessity | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pathological CTG | Failure to Progress in Labour | Patient’s Preference | Other | |||

| Indication for Prior CS | Pathological CTG | 3 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 8 |

| Failure to progress in labour | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 6 | |

| Patient’s preference | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| Other | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | |

| Total | 7 | 6 | 3 | 4 | 20 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cobec, I.M.; Rempen, A.; Anastasiu-Popov, D.-M.; Eftenoiu, A.-E.; Moatar, A.E.; Vlad, T.; Sas, I.; Varzaru, V.B. How the Mode of Delivery Is Influenced by Patient’s Opinions and Risk-Informed Consent in Women with a History of Caesarean Section? Is Vaginal Delivery a Real Option after Caesarean Section? J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4393. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13154393

Cobec IM, Rempen A, Anastasiu-Popov D-M, Eftenoiu A-E, Moatar AE, Vlad T, Sas I, Varzaru VB. How the Mode of Delivery Is Influenced by Patient’s Opinions and Risk-Informed Consent in Women with a History of Caesarean Section? Is Vaginal Delivery a Real Option after Caesarean Section? Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(15):4393. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13154393

Chicago/Turabian StyleCobec, Ionut Marcel, Andreas Rempen, Diana-Maria Anastasiu-Popov, Anca-Elena Eftenoiu, Aurica Elisabeta Moatar, Tania Vlad, Ioan Sas, and Vlad Bogdan Varzaru. 2024. "How the Mode of Delivery Is Influenced by Patient’s Opinions and Risk-Informed Consent in Women with a History of Caesarean Section? Is Vaginal Delivery a Real Option after Caesarean Section?" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 15: 4393. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13154393

APA StyleCobec, I. M., Rempen, A., Anastasiu-Popov, D.-M., Eftenoiu, A.-E., Moatar, A. E., Vlad, T., Sas, I., & Varzaru, V. B. (2024). How the Mode of Delivery Is Influenced by Patient’s Opinions and Risk-Informed Consent in Women with a History of Caesarean Section? Is Vaginal Delivery a Real Option after Caesarean Section? Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(15), 4393. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13154393