Prioritising Appointments by Telephone Interview: Duration from Symptom Onset to Appointment Request Predicts Likelihood of Inflammatory Rheumatic Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

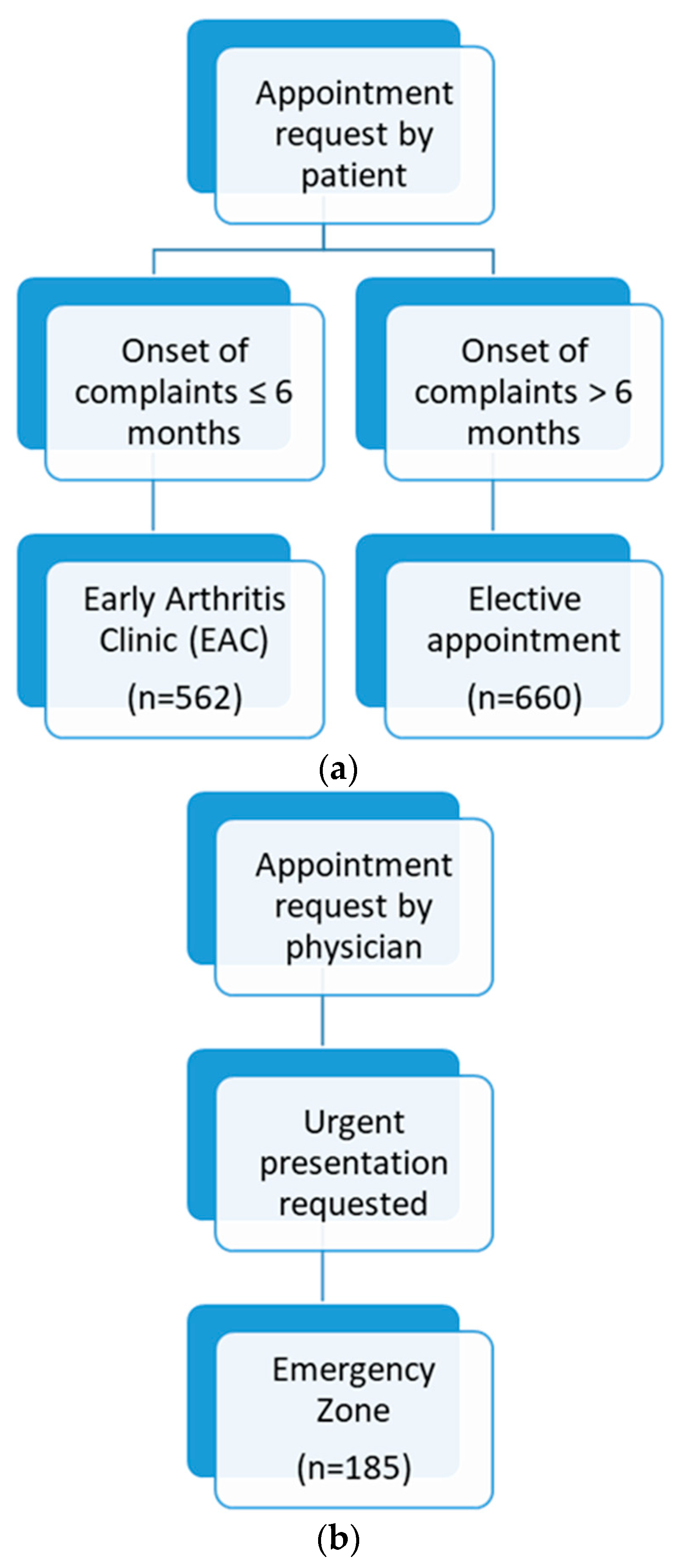

2.1. Patient Recruitment and Data Collection

2.2. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- The present study confirms the high proportion of patients with non-inflammatory complaints at initial presentation, consistent with the literature;

- A duration from symptom onset to appointment request of ≤6 months increases the likelihood of diagnosing an inflammatory rheumatic disease;

- DMARDs were initiated significantly more often in the early arthritis clinic or at emergency visits;

- The algorithm-based allocation approach presented saves time and personal resources, and therefore appears practical for routine care use.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nell, V.P.K.; Machold, K.P.; Eberl, G.; Stamm, T.A.; Uffmann, M.; Smolen, J.S. Benefit of very early referral and very early therapy with disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology 2004, 43, 906–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smolen, J.S.; Landewé, R.B.M.; Bergstra, S.A.; Kerschbaumer, A.; Sepriano, A.; Aletaha, D.; Caporali, R.; Edwards, C.J.; Hyrich, K.L.; Pope, J.E.; et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2022 update. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2023, 82, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benesova, K.; Lorenz, H.M.; Lion, V.; Voigt, A.; Krause, A.; Sander, O.; Schneider, M.; Feuchtenberger, M.; Nigg, A.; Leipe, J.; et al. Early recognition and screening consultation: A necessary way to improve early detection and treatment in rheumatology? Overview of the early recognition and screening consultation models for rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases in Germany. Z. Rheumatol. 2019, 78, 722–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinert, J.; Iking-Konert, C.; Blumenroth, M.; Sander, O.; Richter, J.; Schneider, M. Novel approach for the early detection of inflammatory rheumatic diseases in the population using a mobile screening unit. Z. Rheumatol. 2010, 69, 743–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voigt, A.; Seipelt, E.; Bastian, H.; Juche, A.; Krause, A. Improved early diagnostics of rheumatic diseases: Monocentric experiences with an open rheumatological specialist consultation. Z. Rheumatol. 2018, 77, 844–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gräf, M.; Knitza, J.; Leipe, J.; Krusche, M.; Welcker, M.; Kuhn, S.; Mucke, J.; Hueber, A.J.; Hornig, J.; Klemm, P.; et al. Comparison of physician and artificial intelligence-based symptom checker diagnostic accuracy. Rheumatol. Int. 2022, 42, 2167–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benesova, K.; Hansen, O.; Sander, O.; Feuchtenberger, M.; Nigg, A.; Voigt, A.; Seipelt, E.; Schneider, M.; Lorenz, H.-M.; Krause, A. Further development of regional early care-Many roads lead to Rome: Developmental stages of four established rheumatological early care concepts in different regions of Germany. Z. Rheumatol. 2022, 81, 445–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benesova, K.; Lion, V.; Hansen, O.; Lorenz, H.M. Screened-High remission rates underline the benefit of screening consultation models for early recognition and treatment of rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2020, 79, 1863–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SPSS. SPSS for Windows Release 17.0; IBM: Armonk, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Xiao, L.; Zhu, J.; Qin, Q.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, J.A. Methotrexate use reduces mortality risk in rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2022, 55, 152031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Li, M.; Ye, Z.; Li, C.; Li, Z.; Li, X.; Wu, L.; Liu, S.; Zuo, X.; Zhu, P.; et al. Long-term Outcomes of Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Multicenter Cohort Study from CSTAR Registry. Rheumatol. Immunol. Res. 2021, 2, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Combe, B.; Landewe, R.; Daien, C.I.; Hua, C.; Aletaha, D.; Álvaro-Gracia, J.M.; Bakkers, M.; Brodin, N.; Burmester, G.R.; Codreanu, C.; et al. 2016 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of early arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2017, 76, 948–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinn, M.A.; Emery, P. Window of opportunity in early rheumatoid arthritis: Possibility of altering the disease process with early intervention. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2003, 21, S154–S157. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Villeneuve, E.; Nam, J.L.; Bell, M.J.; Deighton, C.M.; Felson, D.T.; Hazes, J.M.; McInnes, I.B.; Silman, A.J.; Solomon, D.H.; Thompson, A.E.; et al. A systematic literature review of strategies promoting early referral and reducing delays in the diagnosis and management of inflammatory arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2013, 72, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saraiva, L.; Duarte, C. Barriers to the Diagnosis of Early Inflammatory Arthritis: A Literature Review. Open Access Rheumatol. Res. Rev. 2023, 15, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puchner, R.; Janetschko, R.; Kaiser, W.; Linkesch, M.; Steininger, M.; Tremetsberger, R.; Alkin, A.; Machold, K. Efficacy and Outcome of Rapid Access Rheumatology Consultation: An Office-based Pilot Cohort Study. J. Rheumatol. 2016, 43, 1130–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gärtner, M.; Fabrizii, J.P.; Koban, E.; Holbik, M.; Machold, L.P.; Smolen, J.S.; Machold, K.P. Immediate access rheumatology clinic: Efficiency and outcomes. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2012, 71, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarting, A.; Dreher, M.; Assmann, G.; Witte, T.; Hoeper, K.; Schmidt, R.E. Experiences and results from Rheuma-VOR. Z. Rheumatol. 2019, 78, 743–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahluwalia, V.; Lineker, S.; Sweezie, R.; Bell, M.J.; Kendzerska, T.; Widdifield, J.; Bombardier, C.; Allied Health Rheumatology Triage Investigators. The Effect of Triage Assessments on Identifying Inflammatory Arthritis and Reducing Rheumatology Wait Times in Ontario. J. Rheumatol. 2020, 47, 461–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazlewood, G.S.; Barr, S.G.; Lopatina, E.; Marshall, D.A.; Lupton, T.L.; Fritzler, M.J.; Mosher, D.P.; Steber, W.A.; Martin, L. Improving Appropriate Access to Care With Central Referral and Triage in Rheumatology. Arthritis Care Res. 2016, 68, 1547–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrer, C.; Abraham, L.; Jerome, D.; Hochman, J.; Gakhal, N. Triage of Rheumatology Referrals Facilitates Wait Time Benchmarks. J. Rheumatol. 2016, 43, 2064–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpenter, T.; Katz, S.J. Review of a rheumatology triage system: Simple, accurate, and effective. Clin. Rheumatol. 2014, 33, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widdifield, J.; Tu, K.; Carter Thorne, J.; Bombardier, C.; Paterson, J.M.; Jaakkimainen, R.L.; Wing, L.; Butt, D.A.; Ivers, N.; Hofstetter, C.; et al. Patterns of Care Among Patients Referred to Rheumatologists in Ontario, Canada. Arthritis Care Res. 2017, 69, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keyßer, G.; Oye, S.; Feist, T.; Liebhaber, A.; Babinsky, K.; Schobess, R.; Boldemann, R.; Wagner, S.; Linde, T. Improvement of the diagnostic accuracy in patients with suspected rheumatic disease by preselection in the early arthritis clinic: An alternative to the appointment service point model of the Healthcare Improvement Act. Z. Rheumatol. 2016, 75, 812–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuchs, F.; Morf, H.; Mohn, J.; Mühlensiepen, F.; Ignatyev, Y.; Bohr, D.; Araujo, E.; Bergmann, C.; Simon, D.; Kleyer, A.; et al. Diagnostic delay stages and pre-diagnostic treatment in patients with suspected rheumatic diseases before special care consultation: Results of a multicenter-based study. Rheumatol. Int. 2023, 43, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thoms, B.L.; Bonnell, L.N.; Tompkins, B.; Nevares, A.; Lau, C. Predictors of inflammatory arthritis among new rheumatology referrals: A cross-sectional study. Rheumatol. Adv. Pract. 2023, 7, rkad067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nanji, J.A.; Choi, M.; Ferrari, R.; Lyddell, C.; Russell, A.S. Time to consultation and disease-modifying antirheumatic drug treatment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis-northern Alberta perspective. J. Rheumatol. 2012, 39, 707–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knitza, J.; Janousek, L.; Kluge, F.; von der Decken, C.B.; Kleinert, S.; Vorbrüggen, W.; Kleyer, A.; Simon, D.; Hueber, A.J.; Muehlensiepen, F.; et al. Machine learning-based improvement of an online rheumatology referral and triage system. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 954056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knitza, J.; Muehlensiepen, F.; Ignatyev, Y.; Fuchs, F.; Mohn, J.; Simon, D.; Kleyer, A.; Fagni, F.; Boeltz, S.; Morf, H.; et al. Patient’s Perception of Digital Symptom Assessment Technologies in Rheumatology: Results From a Multicentre Study. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 844669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knitza, J.; Mohn, J.; Bergmann, C.; Kampylafka, E.; Hagen, M.; Bohr, D.; Morf, H.; Araujo, E.; Englbrecht, M.; Simon, D.; et al. Accuracy, patient-perceived usability, and acceptance of two symptom checkers (Ada and Rheport) in rheumatology: Interim results from a randomized controlled crossover trial. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2021, 23, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proft, F.; Spiller, L.; Redeker, I.; Protopopov, M.; Rodriguez, V.R.; Muche, B.; Rademacher, J.; Weber, A.-K.; Lüders, S.; Torgutalp, M.; et al. Comparison of an online self-referral tool with a physician-based referral strategy for early recognition of patients with a high probability of axial spa. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2020, 50, 1015–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Patients with Inflammatory Disease (n = 361) | Patients with Non-Inflammatory Disease (n = 1046) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 60.89 ± 17.2 | 51.91 ± 15.5 | p < 0.001 |

| Gender | |||

| Female sex (%) | 181 (51.1%) | 738 (70.6%) | |

| Male sex (%) | 180 (49.9%) | 308 (29.4%) | p < 0.001 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 1.71 ± 2.67 | 0.37 ± 0.69 | p < 0.001 |

| ESR (mm) | 25.28 ± 23.14 | 10.26 ± 9.60 | p < 0.001 |

| Triage: | |||

| Elective appointment | 91 (13.8%) | 569 (86.2%) | |

| Early arthritis clinic (EAC) | 185 (32.9%) | 377 (67.1%) | |

| Emergency appointment | 85 (45.9%) | 100 (54.1%) | p < 0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Feuchtenberger, M.; Kovacs, M.S.; Nigg, A.; Schäfer, A. Prioritising Appointments by Telephone Interview: Duration from Symptom Onset to Appointment Request Predicts Likelihood of Inflammatory Rheumatic Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4551. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13154551

Feuchtenberger M, Kovacs MS, Nigg A, Schäfer A. Prioritising Appointments by Telephone Interview: Duration from Symptom Onset to Appointment Request Predicts Likelihood of Inflammatory Rheumatic Disease. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(15):4551. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13154551

Chicago/Turabian StyleFeuchtenberger, Martin, Magdolna Szilvia Kovacs, Axel Nigg, and Arne Schäfer. 2024. "Prioritising Appointments by Telephone Interview: Duration from Symptom Onset to Appointment Request Predicts Likelihood of Inflammatory Rheumatic Disease" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 15: 4551. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13154551

APA StyleFeuchtenberger, M., Kovacs, M. S., Nigg, A., & Schäfer, A. (2024). Prioritising Appointments by Telephone Interview: Duration from Symptom Onset to Appointment Request Predicts Likelihood of Inflammatory Rheumatic Disease. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(15), 4551. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13154551