Prevalence and Risk Factors of Inappropriate Drug Dosing among Older Adults with Dementia or Cognitive Impairment and Renal Impairment: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

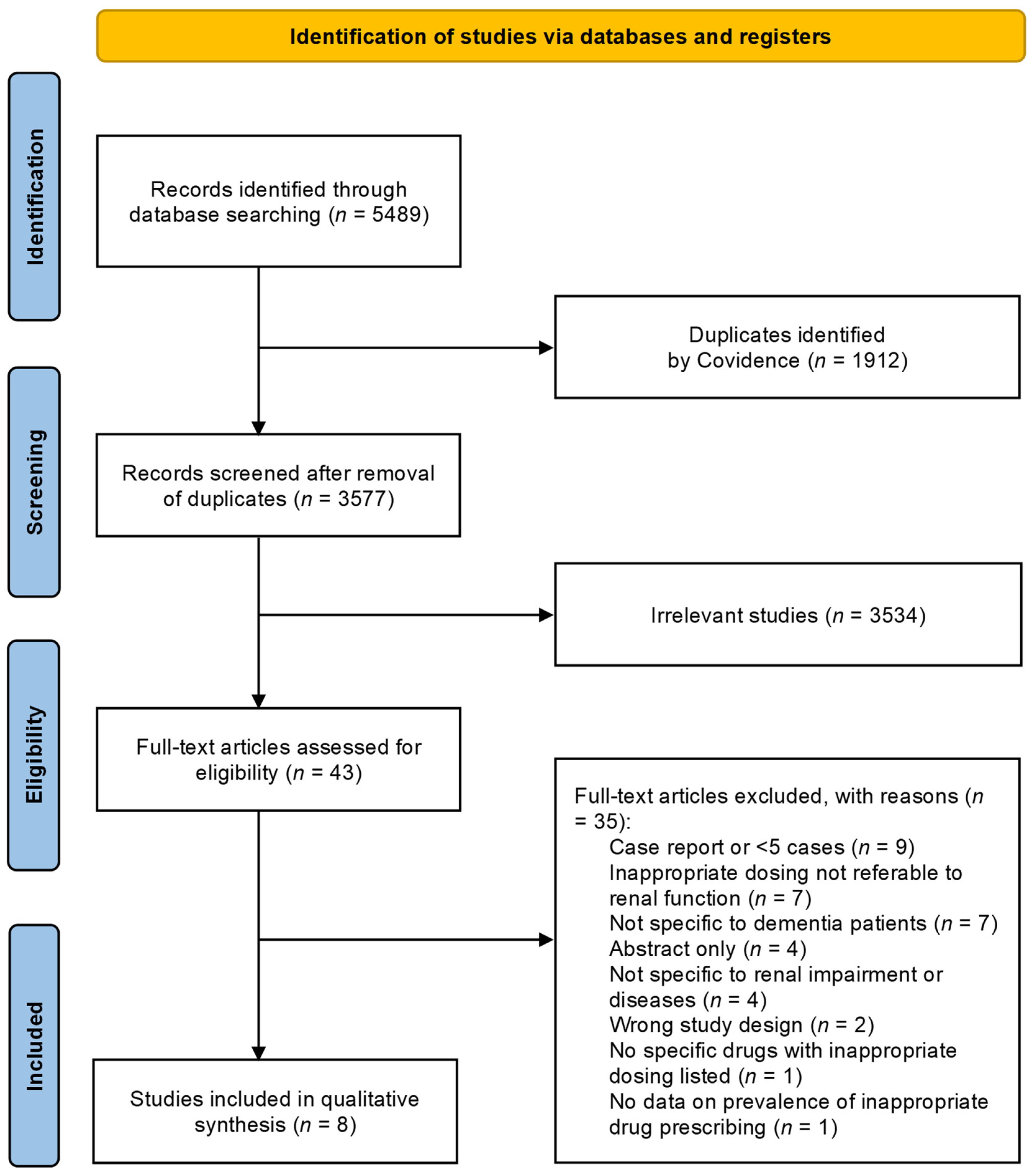

2. Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Data Sources and Search Strategy

2.3. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Definitions of Renal Impairment and Inappropriate Drug Dosing

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Quality Assessment

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Tamura, M.K.; Yaffe, K. Dementia and cognitive impairment in ESRD: Diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. Kidney Int. 2011, 79, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzpatrick, D.; Gallagher, P.F. Polypharmacy: Definition, Epidemiology, Consequences and Solutions. In Optimizing Pharmacotherapy in Older Patients: An Interdisciplinary Approach; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 15–31. [Google Scholar]

- Sell, R.; Schaefer, M. Prevalence and risk factors of drug-related problems identified in pharmacy-based medication reviews. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2020, 42, 588–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Q.N.X.; Ming, L.C.; Abd Wahab, M.S.; Tan, C.S.; Yuda, A.; Hermansyah, A. Drug-related problems among older people with dementia: A systematic review. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2023, 19, 873–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelino, R.L.; Saunder, T.; Kitsos, A.; Peterson, G.M.; Jose, M.; Wimmer, B.; Khanam, M.; Bezabhe, W.; Stankovich, J.; Radford, J. Quality use of medicines in patients with chronic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol. 2020, 21, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezabhe, W.M.; Kitsos, A.; Saunder, T.; Peterson, G.M.; Bereznicki, L.R.; Wimmer, B.C.; Jose, M.; Radford, J. Medication prescribing quality in australian primary care patients with chronic kidney disease. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Government Department of Veterans’ Affairs. M30 Therapeutic Brief. Know Your Patient’s Renal Function—An Important Prescribing Consideration. Available online: https://www.veteransmates.com.au/topic-30-therapeutic-brief (accessed on 3 February 2024).

- Tesfaye, W.H.; Castelino, R.L.; Wimmer, B.C.; Zaidi, S.T.R. Inappropriate prescribing in chronic kidney disease: A systematic review of prevalence, associated clinical outcomes and impact of interventions. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2017, 71, e12960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alruqayb, W.S.; Price, M.J.; Paudyal, V.; Cox, A.R. Drug-related problems in hospitalised patients with chronic kidney disease: A systematic review. Drug Saf. 2021, 44, 1041–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, D.; Asmamaw, G.; Etiso, T.; Bussa, Z. Prevalence of inappropriate drug dose adjustment and associated factors among inpatients with renal impairment in Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. SAGE Open Med. 2023, 11, 20503121221150104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörks, M.; Allers, K.; Schmiemann, G.; Herget-Rosenthal, S.F. Inappropriate medication in non-hospitalized patients with renal insufficiency: A systematic review. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2017, 65, 853–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nothelle, S.K.; Sharma, R.; Oakes, A.; Jackson, M.; Segal, J.B. Factors associated with potentially inappropriate medication use in community-dwelling older adults in the United States: A systematic review. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2019, 27, 408–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, T.; Slonim, K.; Lee, L. Use of potentially inappropriate medications among ambulatory home-dwelling elderly patients with dementia: A review of the literature. Can. Pharm. J. Rev. Des Pharm. Du Can. 2017, 150, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, A.S.; Peterson, G.M.; Bereznicki, L.R.; Curtain, C.M.; Salahudeen, M. Outcomes of medication misadventure among people with cognitive impairment or dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Pharmacother. 2021, 55, 530–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.4 (Updated August 2023); Cochrane: Chichester, UK, 2023; Available online: https://www.training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed on 21 February 2024).

- Amir-Behghadami, M.; Janati, A. Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes and Study (PICOS) design as a framework to formulate eligibility criteria in systematic reviews. Emerg. Med. J. 2020, 37, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.K.; Knicely, D.H.; Grams, M.E. Chronic kidney disease diagnosis and management: A review. JAMA 2019, 322, 1294–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cockcroft, D.W.; Gault, H. Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron 1976, 16, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levey, A.S.; Coresh, J.; Greene, T.; Stevens, L.A.; Zhang, Y.; Hendriksen, S.; Kusek, J.W.; Van Lente, F.; Collaboration* C.K.D.E. Using standardized serum creatinine values in the modification of diet in renal disease study equation for estimating glomerular filtration rate. Ann. Intern. Med. 2006, 145, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levey, A.S.; Stevens, L.A.; Schmid, C.H.; Zhang, Y.; Castro, I.I.I.A.F.; Feldman, H.I.; Kusek, J.W.; Eggers, P.; Van Lente, F.; Greene, T. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 150, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanlon, J.T.; Wang, X.; Handler, S.M.; Weisbord, S.; Pugh, M.J.; Semla, T.; Stone, R.A.; Aspinall, S.L. Potentially inappropriate prescribing of primarily renally cleared medications for older veterans affairs nursing home patients. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2011, 12, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfister, B.; Jonsson, J.; Gustafsson, M. Drug-related problems and medication reviews among old people with dementia. BMC Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2017, 18, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sönnerstam, E.; Sjölander, M.; Gustafsson, M. Inappropriate prescription and renal function among older patients with cognitive impairment. Drugs Aging 2016, 33, 889–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moola, S.M.Z.; Tufanaru, C.; Aromataris, E.; Sears, K.; Sfetcu, R.; Currie, M.; Qureshi, R.; Mattis, P.; Lisy, K.; Mu, P.-F. Chapter 7: Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2020; Available online: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global (accessed on 3 February 2024).

- Delgado, J.; Jones, L.; Bradley, M.C.; Allan, L.M.; Ballard, C.; Clare, L.; Fortinsky, R.H.; Hughes, C.M.; Melzer, D. Potentially inappropriate prescribing in dementia, multi-morbidity and incidence of adverse health outcomes. Age Ageing 2021, 50, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolder, C.; Nelson, M.; McKinsey, J. Memantine dosing in patients with dementia. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2009, 17, 170–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muanda, F.T.; Weir, M.A.; Bathini, L.; Blake, P.G.; Chauvin, K.; Dixon, S.N.; McArthur, E.; Sontrop, J.M.; Moist, L.; Garg, A.X. Association of baclofen with encephalopathy in patients with chronic kidney disease. JAMA 2019, 322, 1987–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt-Mende, K.; Wettermark, B.; Andersen, M.; Elsevier, M.; Carrero, J.J.; Shemeikka, T.; Hasselström, J. Prevalence of renally inappropriate medicines in older people with renal impairment—A cross-sectional register-based study in a large primary care population. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2019, 124, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Secora, A.; Alexander, G.C.; Ballew, S.H.; Coresh, J.; Grams, M.E. Kidney function, polypharmacy, and potentially inappropriate medication use in a community-based cohort of older adults. Drugs Aging 2018, 35, 735–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runesson, B.; Gasparini, A.; Qureshi, A.R.; Norin, O.; Evans, M.; Barany, P.; Wettermark, B.; Elinder, C.G.; Carrero, J.J. The Stockholm CREAtinine Measurements (SCREAM) project: Protocol overview and regional representativeness. Clin. Kidney J. 2016, 9, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The ARIC Investigators. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study: Design and objectives. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1989, 129, 687–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, M.; Sjölander, M.; Pfister, B.; Jonsson, J.; Schneede, J.; Lövheim, H. Pharmacist participation in hospital ward teams and hospital readmission rates among people with dementia: A randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2017, 73, 827–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, S.; Forbes, K.; Hanks, G.; Ferro, C.; Chambers, E. A systematic review of the use of opioid medication for those with moderate to severe cancer pain and renal impairment: A European Palliative Care Research Collaborative opioid guidelines project. Palliat. Med. 2011, 25, 525–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Mahony, D.; O'Sullivan, D.; Byrne, S.; O'Connor, M.N.; Ryan, C.; Gallagher, P. STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: Version 2. Age Ageing 2014, 44, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forest Pharmaceuticals, Inc.: Namenda prescribing information, St. Louis. 2007. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2013/021487s010s012s014,021627s008lbl.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Hanlon, J.T.; Aspinall, S.L.; Semla, T.P.; Weisbord, S.D.; Fried, L.F.; Good, C.B.; Fine, M.J.; Stone, R.A.; Pugh, M.J.V.; Rossi, M.I. Consensus guidelines for oral dosing of primarily renally cleared medications in older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2009, 57, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VA/DOD Clinical Practice Guidelines. Management of Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) in Critical Care. Available online: http://www.healthquality.va.gov/Chronic_Kidney_Disease_Clinical_Practice_Guideline.asp (accessed on 15 November 2009).

- Cipolle, R.; Strand, L.; Morely, P. Pharmaceutical Care Practice; The McGraw-Hill Companies Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- The National Board of Health and Welfare. Indikatorer för God Läkemedelsterapi Hos Äldre. In Eng. Indicators for Evaluating the Quality of Older People’s Drug Therapy; The National Board of Health and Welfare: Stockholm, Sweden; Available online: https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/artikelkatalog/ovrigt/2017-6-7.pdf (accessed on 7 December 2015).

- Health and Medical Care Administration. Commercially Independent Drug Information Aimed at Doctors and Healthcare Professionals; Hälso- och sjukvårdsförvaltningen, Sweden. Available online: https://janusinfo.se/inenglish.4.7e3d365215ec82458644daab.html (accessed on 11 June 2018).

- Micromedex® 1.0 (Electronic Version). Truven Health Analytics. Greenwood Village, Colorado, USA. Available online: https://www.micromedexsolutions.com/home/dispatch/ssl/true (accessed on 12 August 2016).

- Semla, T.P.; Beizer, J.L.; Higbee, M.D. Geriatric Dosage Handbook, 16th ed.; Lexi-Comp: Ohio, OH, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Toussaint, N.D.; Lau, K.K.; Strauss, B.J.; Polkinghorne, K.R.; Kerr, P.G. Effect of alendronate on vascular calcification in CKD stages 3 and 4: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2010, 56, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mari, A.; Antonelli, A.; Cindolo, L.; Fusco, F.; Minervini, A.; De Nunzio, C. Alfuzosin for the medical treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia and lower urinary tract symptoms: A systematic review of the literature and narrative synthesis. Ther. Adv. Urol. 2021, 13, 1756287221993283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalbeth, N.; Stamp, L. Allopurinol dosing in renal impairment: Walking the tightrope between adequate urate lowering and adverse events. Semin. Dial. 2007, 20, 391–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). KDIGO 2012 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Available online: https://kdigo.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/KDIGO_2012_CKD_GL.pdf (accessed on 27 February 2024).

- El-Husseini, A.; Sabucedo, A.; Lamarche, J.; Courville, C.; Peguero, A. Baclofen toxicity in patients with advanced nephropathy: Proposal for new labeling. Am. J. Nephrol. 2011, 34, 491–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, A.K.; Chang, T.I.; Cushman, W.C.; Furth, S.L.; Hou, F.F.; Ix, J.H.; Knoll, G.A.; Muntner, P.; Pecoits-Filho, R.; Sarnak, M.J. KDIGO 2021 clinical practice guideline for the management of blood pressure in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2021, 99, S1–S87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fillastre, J.; Ings, R.; Leroy, A.; Humbert, G.; Godin, M. Pharmacokinetics of cefotaxime in patients with chronic renal impairment (author's transl). La Nouv. Presse Medicale 1981, 10, 574–579. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, R.D.; Ferner, R.; Pearce, G.L.; Dunn, N.; Shakir, S. Sedation with “non-sedating” antihistamines: Four prescription-event monitoring studies in general practiceCommentary: Reporting of adverse events is worth the effort. BMJ 2000, 320, 1184–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lexicomp. (n.d.). Ciprofloxacin (Systemic): Drug Information. UpToDate. Available online: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/ciprofloxacin-systemic-drug-information?search=ciprofloxacin&source=panel_search_result&selectedTitle=1%7E142&usage_type=panel&showDrugLabel=true&display_rank=1#F50990660 (accessed on 24 February 2024).

- Richette, P.; Doherty, M.; Pascual, E.; Barskova, V.; Becce, F.; Castañeda-Sanabria, J.; Coyfish, M.; Guillo, S.; Jansen, T.; Janssens, H. 2016 updated EULAR evidence-based recommendations for the management of gout. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2017, 76, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulseth, M.P.; Wittkowsky, A.K.; Fanikos, J.; Spinler, S.A.; Dager, W.E.; Nutescu, E.A. Dabigatran etexilate in clinical practice: Confronting challenges to improve safety and effectiveness. Pharmacother. J. Hum. Pharmacol. Drug Ther. 2011, 31, 1232–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lexicomp. (n.d.). Enalapril: Drug Information. UpToDate. Available online: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/enalapril-drug-information?search=enalapril&selectedTitle=1%7E96&usage_type=panel&display_rank=1&kp_tab=drug_general&source=panel_search_result (accessed on 27 February 2024).

- Turpie, A.G.; Lensing, A.W.; Fuji, T.; Boyle, D.A. Pharmacokinetic and clinical data supporting the use of fondaparinux 1.5 mg once daily in the prevention of venous thromboembolism in renally impaired patients. Blood Coagul. Fibrinolysis 2009, 20, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mismetti, P.; Samama, C.-M.; Rosencher, N.; Vielpeau, C.; Nguyen, P.; Deygas, B.; Presles, E.; Laporte, S.; Group, P.S. Venous thromboembolism prevention with fondaparinux 1.5 mg in renally impaired patients undergoing major orthopaedic surgery. Thromb. Haemost. 2012, 107, 1151–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lexicomp. (n.d.). Galantamine: Drug Information. UpToDate. Available online: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/galantamine-drug-information?sectionName=Kidney%20Impairment%20%28Adult%29&topicId=8739&search=galantamine&usage_type=panel&anchor=F50991207&source=panel_search_result&selectedTitle=1%7E22&showDrugLabel=true&kp_tab=drug_general&display_rank=1#F50991207 (accessed on 24 February 2024).

- Alsahli, M.; Gerich, J.E. Hypoglycemia in patients with diabetes and renal disease. J. Clin. Med. 2015, 4, 948–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golightly, L.K.; Teitelbaum, I.; Kiser, T.H.; Levin, D.; Barber, G.; Jones, M.; Stolpman, N.M.; Lundin, K.S. Renal Pharmacotherapy: Dosage Adjustment of Medications Eliminated by the Kidneys; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 1–752. [Google Scholar]

- Koncicki, H.M.; Unruh, M.; Schell, J.O. Pain management in CKD: A guide for nephrology providers. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2017, 69, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The 2023 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2023 updated AGS Beers Criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2023, 71, 2052–2081. Available online: https://agsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/jgs.18372 (accessed on 23 July 2024). [CrossRef]

- Melamed, M.L.; Blackwell, T.; Neugarten, J.; Arnsten, J.H.; Ensrud, K.E.; Ishani, A.; Cummings, S.R.; Silbiger, S.R. Raloxifene, a selective estrogen receptor modulator, is renoprotective: A post-hoc analysis. Kidney Int. 2011, 79, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lexicomp. (n.d.). Spironolactone: Drug Information. UpToDate. Available online: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/spironolactone-drug-information?search=Spironolactone&source=panel_search_result&selectedTitle=1%7E148&usage_type=panel&kp_tab=drug_general&display_rank=1 (accessed on 24 February 2024).

- Hemstreet, B.A. Use of sucralfate in renal failure. Ann. Pharmacother. 2001, 35, 360–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banovic, S.; Zunic, L.J.; Sinanovic, O. Communication difficulties as a result of dementia. Mater. Socio-Medica 2018, 30, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, A.J.; Etherton-Beer, C.D.; Clifford, R.M.; Potter, K.; Page, A.T. Exploring stakeholder roles in medication management for people living with dementia. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2021, 17, 707–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.S.; Hoyte, C. Review of biguanide (metformin) toxicity. J. Intensive Care Med. 2019, 34, 863–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFronzo, R.; Fleming, G.A.; Chen, K.; Bicsak, T.A. Metformin-associated lactic acidosis: Current perspectives on causes and risk. Metabolism 2016, 65, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association of British Clinical Diabetologists. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Management of Hyperglycaemia in Adults with Diabetic Kidney Disease. 2021 Update. Available online: https://ukkidney.org/sites/renal.org/files/Managing%20hyperglycaemia%20in%20people%20with%20DKD_final%20draft.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Inzucchi, S.E.; Lipska, K.J.; Mayo, H.; Bailey, C.J.; McGuire, D.K. Metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes and kidney disease: A systematic review. JAMA 2014, 312, 2668–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imam, T.H. Changes in metformin use in chronic kidney disease. Clin. Kidney J. 2017, 10, 301–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, D. Association between non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and cognitive decline: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Drugs Aging 2016, 33, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppmann, R.A.; Peden, J.G.; Ober, S.K. Central nervous system side effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: Aseptic meningitis, psychosis, and cognitive dysfunction. Arch. Intern. Med. 1991, 151, 1309–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, K.Y.; Cardosa, M.S.; Chaiamnuay, S.; Hidayat, R.; Ho, H.Q.T.; Kamil, O.; Mokhtar, S.A.; Nakata, K.; Navarra, S.V.; Nguyen, V.H. Practice advisory on the appropriate use of NSAIDs in primary care. J. Pain Res. 2020, 13, 1925–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornhuber, J.; Kennepohl, E.M.; Bleich, S.; Wiltfang, J.; Kraus, T.; Reulbach, U.; Meineke, I. Memantine pharmacotherapy: A naturalistic study using a population pharmacokinetic approach. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2007, 46, 599–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, M.; Lee, J.; Lee, T.Y.; Kim, S.B. Prevalence and risk factors of baclofen neurotoxicity in patients with severely impaired renal function. Nefrología 2020, 40, 543–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauvin, K.J.; Blake, P.G.; Garg, A.X.; Weir, M.A.; Bathini, L.; Dixon, S.N.; McArthur, E.; Sontrop, J.M.; Moist, L.; Kim, R.B. Baclofen has a risk of encephalopathy in older adults receiving dialysis. Kidney Int. 2020, 98, 979–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romito, J.W.; Turner, E.R.; Rosener, J.A.; Coldiron, L.; Udipi, A.; Nohrn, L.; Tausiani, J.; Romito, B.T. Baclofen therapeutics, toxicity, and withdrawal: A narrative review. SAGE Open Med. 2021, 9, 20503121211022197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The 2023 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2023 updated AGS Beers Criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2023, 1–30. Available online: https://sbgg.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/1-American-Geriatrics-Society-2023.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Hwang, Y.J.; Chang, A.R.; Brotman, D.J.; Inker, L.A.; Grams, M.E.; Shin, J.I. Baclofen and the Risk of Encephalopathy: A Real-World, Active-Comparator Cohort Study. Mayo. Clin. Proc. 2023, 98, 676–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Killam-Worrall, L.; Brand, R.; Castro, J.R.; Patel, D.S.; Huynh, K.; Lindley, B.; Torres, B.P. Baclofen and Tizanidine Adverse Effects Observed Among Community-Dwelling Adults Above the Age of 50 Years: A Systematic Review. Ann. Pharmacother. 2024, 58, 523–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanagaratnam, L.; Dramé, M.; Trenque, T.; Oubaya, N.; Nazeyrollas, P.; Novella, J.-L.; Jolly, D.; Mahmoudi, R. Adverse drug reactions in elderly patients with cognitive disorders: A systematic review. Maturitas 2016, 85, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, M.H.; Mestres, C.; Modamio, P.; Junyent, J.; Costa-Tutusaus, L.; Lastra, C.F.; Mariño, E.L. Adverse drug events in patients with dementia and neuropsychiatric/behavioral, and psychological symptoms, a one-year prospective study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beuscart, J.-B.; Pelayo, S.; Robert, L.; Thevelin, S.; Marien, S.; Dalleur, O. Medication review and reconciliation in older adults. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2021, 12, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeola, M.; Fernandez, J.; Sherer, J. Medication management in older adults with dementia. In Dementia and Chronic Disease: Management of Comorbid Medical Conditions; Springer Cham: Texas, TX, USA, 2020; pp. 39–51. [Google Scholar]

- Reeve, E.; Simon Bell, J.; NHilmer, S. Barriers to optimising prescribing and deprescribing in older adults with dementia: A narrative review. Curr. Clin. Pharmacol. 2015, 10, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiatti, C.; Bustacchini, S.; Furneri, G.; Mantovani, L.; Cristiani, M.; Misuraca, C.; Lattanzio, F. The economic burden of inappropriate drug prescribing, lack of adherence and compliance, adverse drug events in older people: A systematic review. Drug Saf. 2012, 35, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sköldunger, A.; Fastbom, J.; Wimo, A.; Fratiglioni, L.; Johnell, K. Impact of inappropriate drug use on hospitalizations, mortality, and costs in older persons and persons with dementia: Findings from the SNAC study. Drugs Aging 2015, 32, 671–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component | Description |

|---|---|

| Population (P) | Studies related to dementia or cognitive impairment with co-existing renal impairment in older patients (≥65 years old). |

| Intervention (I) | Not applicable. |

| Comparison (C) | Not applicable. |

| Outcomes (O) | Identification of the prevalence of inappropriate drug dosing, and examination of the medications and factors associated with inappropriate drug dosing. |

| Study Design (S) | The review encompasses a variety of study designs, such as cohort studies and cross-sectional studies, to ensure a comprehensive synthesis of relevant evidence. |

| Author, Year, Study Location | Study Design | Healthcare Settings | Source of Data | Methods and Resources Used to Detect Inappropriate Drug Dosing | Study Size (n) | Dementia/Cognitive Impairment Reported (%) | Medications Examined | Patients with Dementia Who Had Renal Impairment, n | Patients with Dementia or Cognitive Impairment Who Had Renal Impairment and Inappropriate Drug Dosing, n (%) | Proportion of Patients with Dementia or Cognitive Impairment Who Had Inappropriate Drug Dosing Among Different Medications or Classes of Medications According to Renal Function (%) | Assessment of Study Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delgado et al. 2021 [26], United Kingdom | Retrospective cohort, multi-centre | Community, nursing homes or aged care facilities | Primary care records via CPRD, UK | STOPP Version 2 criteria [34] | 54,638 | 11,175 (20.4) | NSAIDs Metformin Digoxin Direct thrombin inhibitors (e.g., dabigatran) Colchicine Factor Xa inhibitors (e.g., rivaroxaban, apixaban) | 3292 | 1728 (52.5) (dementia only) | NSAIDs: 1322/1728 (76.5) * Metformin: 340/1728 (19.7) * Digoxin: 43/1728 (2.5) * Direct thrombin inhibitors (e.g., dabigatran): 22/1728 (1.3) * Colchicine: 1/1728 (0.06) * | High |

| Dolder et al. 2009 [27], United States | Retrospective cohort, single centre | Hospitals | Patients’ medical charts, geriatric psychiatry inpatient ward, Carolina, US | Summary of product characteristics (memantine only) [35] | 70 | 70 (100) | Memantine (n = 70) | 15 | 9 (60) (dementia only) | Memantine (oral dose at ≥10 mg/day): 9/70 (12.8) | Low |

| Hanlon et al. 2011 [22], United States | Retrospective cohort, multi-centre | Nursing homes | MDS data, any one of the 133 VAs nursing homes, US | Consensus guidelines for oral dosing of primarily renally cleared medications in older adults [36] and DoVA/DoD CKD guidelines [37] | 1304 | 437 (33.5) | Memantine (n = 90) | Not possible to extract | 1 (dementia only) | Memantine (oral dose at ≥10 mg/day): 1/90 (1.1) ¶ | Moderate |

| Muanda et al. 2019 [28], Canada | Retrospective cohort, multi-centre | General population | Linked administrative health care databases at the ICES, Ontario, Canada | Based on an SR to determine the median dose reported in cases of baclofen toxicity in patients with CKD (baclofen only) [28] | 15,942 | 1830 (11.5) | Baclofen (n = 1830) | 1830 | 945 (51.6) (dementia only) | Baclofen (oral dose at ≥20 mg/day): 945/1830 (51.6) | Moderate |

| Pfister et al. 2017 [23], Sweden | Retrospective cohort, multi-centre | Hospitals and nursing homes | Data for patients admitted to acute internal medicine ward, orthopedic clinic, Umeå University Hospital and medicine wards, County Hospital, Skellefteå, Sweden | Classification of drug-related problems by the modified version of criteria in Cipolle et al. [38] and Swedish criteria and inappropriate drug classification according to renal function and disease [39] | 212 | 212 (100) | No restrictions. OTC drugs were excluded | NR | 24 (dementia or cognitive impairment) | Memantine: 3/24 (12.5) * Digoxin: 3/24 (12.5) * Metformin: 3/24 (12.5) * Glibenclamide: 2/24 (8.3) * Morphine: 2/24 (8.3) * Tramadol: 2/24 (8.3) * Allopurinol: 1/24 (4.2) * Enalapril: 1/24 (4.2) * Fondaparinux: 1/24 (4.2) * Glipizide: 1/24 (4.2) * Sucralfate: 1/24 (4.2) * Hydrochlorothiazide: 1/24 (4.2) * Ibuprofen: 1/24 (4.2) * Ketoprofen: 1/24 (4.2) * Nitrofurantoin: 1/24 (4.2) * | Moderate |

| Schmidt-Mende et al. 2019 [29], Sweden | Retrospective cohort, multi-centre | Community | Primary care records via SCREAM database, a repository of laboratory data of individuals, Stockholm, Sweden | Janusmed Drugs and Renal function version 2016 [40] | 32,533 | 1353 (4.1) | Subset of 50 drugs (CKD stage 3) and subset of 66 drugs (CKD stage 4). Only memantine could be examined in patients with dementia (n = 24) | 108 | 13 (12) (dementia only) | Memantine (oral dose at ≥10 mg/day): 13/24 (54.2) | High |

| Secora et al. 2018 [30], United States | Retrospective cohort, multi-centre | Community and hospitals | Data extracted from the ARIC study, a project based on laboratory and physical examination data, four US communities | Micromedex [41] | 6392 | 5 (0.1) | Subset of 554 drugs. Only galantamine could be examined in patients with dementia (n = 5) | 5 | 0 (0) | Galantamine (use if eCrCl <9 mL/min): 0/5 (0) | Moderate |

| Sönnerstam et al. 2016 [24], Sweden | Retrospective cohort, multi-centre | Hospitals and nursing homes | Data for patients admitted to acute internal medicine or orthopaedic ward, Norrland University Hospital and medical ward, County Hospital, Skelleftea°, Sweden | Geriatric Dosage Handbook guidelines [42] and an SR on the use of opioid medication for those with moderate to severe cancer pain and renal impairment (morphine only) [43] | 428 | 428 (100) | No restrictions | Not possible to extract | 50 (dementia or cognitive impairment) | Metformin: 12/50 (24) * Allopurinol: 8/50 (16) * Morphine: 5/50 (10) * Spironolactone: 3/50 (6) * Nitrofurantoin: 3/50 (6) * Hydrochlorothiazide: 2/50 (4) * Glibenclamide: 2/50 (4) * Alendronate: 2/50 (4) * Memantine: 2/50 (4) * Ketoprofen: 1/50 (2) * Tramadol: 1/50 (2) * Raloxifene: 1/50 (2) * Alfuzosin: 1/50 (2) * Amoxicillin: 1/50 (2) * Ampicillin: 1/50 (2) * Bendroflumethiazide: 1/50 (2) * Cefotaxime: 1/50 (2) * Cetirizine: 1/50 (2) * Ciprofloxacin: 1/50 (2) * Galantamine: 1/50 (2) * | Moderate |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alhumaid, S.; Bezabhe, W.M.; Williams, M.; Peterson, G.M. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Inappropriate Drug Dosing among Older Adults with Dementia or Cognitive Impairment and Renal Impairment: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 5658. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13195658

Alhumaid S, Bezabhe WM, Williams M, Peterson GM. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Inappropriate Drug Dosing among Older Adults with Dementia or Cognitive Impairment and Renal Impairment: A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(19):5658. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13195658

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlhumaid, Saad, Woldesellassie M. Bezabhe, Mackenzie Williams, and Gregory M. Peterson. 2024. "Prevalence and Risk Factors of Inappropriate Drug Dosing among Older Adults with Dementia or Cognitive Impairment and Renal Impairment: A Systematic Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 19: 5658. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13195658

APA StyleAlhumaid, S., Bezabhe, W. M., Williams, M., & Peterson, G. M. (2024). Prevalence and Risk Factors of Inappropriate Drug Dosing among Older Adults with Dementia or Cognitive Impairment and Renal Impairment: A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(19), 5658. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13195658