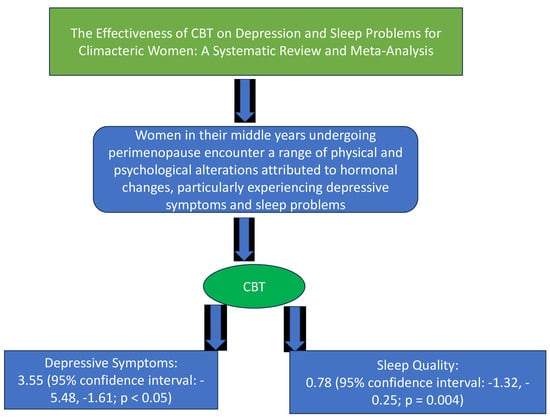

The Effectiveness of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy on Depression and Sleep Problems for Climacteric Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- To establish the overall features of CBT in the search process;

- (2)

- To evaluate the effect size of the impact of CBT in mitigating depressive symptoms;

- (3)

- To measure the effect size of the effect of CBT on issues related to sleep.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Procedures

2.2. Inclusion Criteria and Criteria of Material Selection

2.3. Search Strategy

2.4. Study Selection and Data Extraction

2.5. Risk of Bias Assessment and Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Attributes of the Participants

3.2. Features of the Studies

3.3. Efficacy of the Interventions on Depressive Symptoms and Sleep-Related Issues

3.4. Publication Bias

3.5. Subgroup Analyses

4. Discussion

4.1. Findings

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bang, Y.Y. Convergence analysis of Depression managing Program for Menopausal Women in Korea. J. Korea Converg. Soc. 2019, 10, 257–264. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.N. Effects of Menopause Symptoms on Stress and Quality of Life Satisfaction. Int. J. Contents 2020, 20, 198–205. [Google Scholar]

- Santoro, N.; Epperson, C.N.; Mathews, S.B. Menopausal Symptoms and Their Management. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 2015, 44, 497–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, H.K.; Cha, B.K. Influencing Factors of Climacteric Women’s Depression. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. 2003, 7, 972–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vivian-Tayler, J.; Hickey, M. Menopause and depression: Is there a link? Maturitas 2014, 79, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanter, J.W.; Busch, A.M.; Weeks, C.E.; Landes, S.J. The nature of clinical depression: Symptoms, syndromes, and behavior analysis. Behav. Anal. 2008, 31, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.Y.; Park, J.H. Poor Sleep Quality and Its Effect on Quality of Life in the Elderly with Late Life Depression. J. Korean Soc. Biol. Ther. Psychiatry 2014, 21, 74–80. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.H.; Cho, M.J.; Hong, J.P.; Bae, J.N.; Cho, S.J.; Hahm, B.J.; Lee, D.W.; Park, J.I.; Lee, J.Y.; Jeon, H.J.; et al. Gender Differences in Depressive Symptom Profile: Results from Nationwide General Population Surveys in Korea. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2015, 30, 1659–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, E.J.; Choi, S.E. The Effects of Auricular Acupressure Therapy on Sleep Disorder and Fatigue in Menopausal Women. J. Korean Acad. Community Health Nurs. 2020, 31, 447–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, J.H.; Choi, T.Y.; Lee, M.S.; Song, E.H.; Ang, L.; Park, S.J. Sanjoin-tang (Suanzaoren decoction) for Insomnia in Menopausal Syndromes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Soc. Prev. Korean Med. 2020, 24, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Javaheri, S.; Redline, S. Insomnia and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease. Chest 2017, 152, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benca, R.M.; Peterson, M.J. Insomnia and depression. Sleep Med. 2008, 9 (Suppl. S1), S3–S9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asarnow, L.D.; Manber, R. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia in Depression. Sleep Med. Clin. 2019, 14, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oei, T.P.; Shuttlewood, G.J. Specific and nonspecific factors in psychotherapy: A case of cognitive therapy for depression. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 1996, 16, 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochrane Collaboration. Available online: http://www.cochrane.org/ (accessed on 2 April 2023).

- Higgins, J.P.; Whitehead, A.; Turner, R.M. Meta-analysis of continuous outcome data from individual patients. Stat. Med. 2001, 20, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelaziz, E.M.; Elsharkawy, N.B.; Mohamed, S.M. Efficacy of Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy on sleeping difficulties in menopausal women: A randomized controlled trial. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2022, 58, 1907–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drake, C.L.; Kalmbach, D.A.; Arndt, J.T.; Cheng, P.; Tonnu, C.V.; Cuamatzi-Castelan, T.; Fellman-Couture, C. Treating chronic insomnia in postmenopausal women; a randomized clinical trial comparing cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia, sleep restriction therapy, and sleep hygiene education. Sleep 2019, 42, zsy217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, S.M.; Haber, E.; McCabe, R.E.; Soares, C.N. Cognitive-behavioral group treatment for menopausal symptoms; a pilot study. Arch. Women Ment. Health 2019, 16, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, O.K.; Lee, B.G.; Choi, E.; Choi, S.J. Efficacy of Cognitive Behavioral Treatment for Insomnia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2020, 42, 1104–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardy, C.; Griffiths, A.; Norton, S.; Hunter, M.S. Self-help cognitive behavior therapy for working women with problematic hot flushes and night sweats (MENOS@Work): A multicenter randomized controlled trial. Menopause 2017, 25, 508–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalmbach, D.A.; Chng, P.; Arnedt, J.T.; Anderson, J.R.; Roth, T.; Fllman-Couture, C.; Williams, R.A.; Drake, C.L. Treating insomnia improves depression, maladaptive thinking, and hyperarousal in postmenopausal women: Comparing cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBTI), sleep restriction therapy, and sleep hygiene education. Sleep Med. 2019, 55, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalmbach, D.A.; Cheng, P.; Arnedt, J.T.; Cuamatzi-Castelan, A.; Atkinson, R.L.; Fellman-couture, C.; Rohrs, T.; Drake, C.L. Improving Daytime Functioning, Work Performance, and Quality of Life in Postmenopausal Women with Insomnia: Comparing Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia, Sleep Restriction Therapy, and Sleep Hygiene Education. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2019, 15, 999–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCurry, S.M.; Guthrie, K.A.; Morin, C.M.; Woods, N.F.; Landis, C.A.; Ensrud, K.E.; Larson, J.C.; Joffe, H.; Cohen, L.S.; Hunt, J.R.; et al. Telephone-Based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia in Perimenopausal and Postmenopausal Women with Vasomotor Symptoms: A MsFLASH Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 2016, 176, 913–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, N.V.; Mkarappa, D.B. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression among menopausal woman: A randomized controlled trial. J. Family Med. Prim. Care 2019, 8, 1002–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalton, J.E.; Bolen, S.D.; Mascha, E.J. Publication bias: The elephant in the review. Anesth. Analg. 2016, 123, 812–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Oh, P.J. Cognitive behavioral therapy for primary insomnia: A meta-analysis. J. Korea Acad.-Ind. Coop. Soc. 2016, 17, 407–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiskoo, G.; van der Kooi, A.L.; Busschbach, J.; Laven, J.; Beerthuizen, A. Cognitive behavioural therapy for depression in women with PCOS: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2022, 45, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, C.M.; Hernanadez-Galan, L.; Mbuagbaw, L.; Ewuise, J.E.; Thabane, L.; Shea, A.K. Behavioral intervention for improving sleep outcomes in menopausal women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Menopause 2022, 29, 1210–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grey, I.; Arora, T.; Thomas, J.; Saneh, A.; Tohme, P. The role of perceived social support on depression and sleep during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 293, 113452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Sample Size (N) | Age (Mean + SD) | Intervention 1. Mode of Therapy 2. Duration/No. of Sessions 3. Min/Session 4. Provider | Control | Follow-Up Times | Outcomes (Scale) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdelaziz et al. (2022) [17] Saudi Arabia | 80 | 53.06 ± 4.28 | 1. Group (online) 2. 6 online modules 3. 20–30 min 4. Researchers | Usual care | 6 weeks | Primary variables: PSQI ISI Secondary variables: Sleep diary (SOL, frequency of nighttime awakenings, sleep quality, TIB, TST, and sleep efficiency) |

| Drake et al. (2019) [18] USA | 150 | 56.44 ± 5.64 | 1. Individual (in person) 2. 6 weekly sessions 3. Unclear 4. Clinical psychologist | Minimal intervention | 2 weeks post-treatment and at 6 months | ISI, FORD, TST, SOL, nighttime awakenings, waking after sleep, and sleep efficiency |

| Green et al. (2019) [19] Canada | 90 | Intervention 53.27 ± 3.69 Control 52.88 ± 4.39 | 1. Group (in person) 2. 12 weekly sessions 3. 120 4. Psychologists and graduate-level trainees | Wait-list | 12 weeks post-baseline, and at 3 months post- treatment | BDI-II, MADRS, PSQI, HAM, FSFI, and GCS-sex |

| Ham et al. (2020) [20] South Korea | 44 | Intervention 53.83 ± 6.64 Control 55.45 ± 4.43 | 1. Group and individual 2. Weekly sessions over 4 weeks 3. 30 to 60 min 4. Psychologist and psychiatrist | Group education | 1 month and 12 months | CES-D, PSQI, ISI, and MenQoL |

| Hardy et al. (2018) [21] UK | 124 | 54.09 ± 3.4 | 1. Individual 2. Self-help Cognitive Behavioral Therapy over 4 weeks 3. Unclear 4. Self-help | No treatment waitlist control | 6 and 20 weeks post-randomization | PSQI, HFRS, HF frequency, HFNS beliefs and behaviors, MRQ, WHO, and WSAS |

| Kalmbach et al. (2019) [22] USA | 117 | 56.34 ± 5.41 | 1. Group 2. 6 face-to-face sleep therapy sessions 3. Unclear 4. Registered nurse | Sleep hygiene education | 6 months | BDI-II, DBAS, PSAS Cognitive, ERRI, PSWQ, and PSAS Somatic |

| Kalmbach et al. (2019) [23] USA | 150 | 56.44 ± 5.64 | 1. Individual (in person) 2. 6 weekly sessions 3. Unclear 4. Registered nurse | Sleep hygiene education | Post-treatment and at 6 months | ESS, diary-based daytime sleepiness and FSS |

| McCurry et al. (2016) [24] USA | 88 | Intervention 55.0 ± 3.5 Control 54.7 ± 4.7 | 1. Individual (in person) 2. 6 CBTs in 8 weeks 3. 20–30 min 4. CBT experts (coaches) | Menopause education control (phone session) | 8 and 24 weeks post-randomization | ISI, PSQI, sleep diary, diary of wake time after sleep onset, diary of total sleep time, and diary of sleep efficiency |

| Reddy et al. (2019) [25] India | 80 | Intervention 48.63 ± 0.55 Control 49.16 ± 0.8 | 1. Individual (in person) 2. 6 weekly group CBT sessions 3. 50–60 min 4. Primary provider | TAU | 1 month and 6 months | CES-D |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, J.-H.; Yu, H.-J. The Effectiveness of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy on Depression and Sleep Problems for Climacteric Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 412. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13020412

Kim J-H, Yu H-J. The Effectiveness of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy on Depression and Sleep Problems for Climacteric Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(2):412. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13020412

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Ji-Hyun, and Hea-Jin Yu. 2024. "The Effectiveness of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy on Depression and Sleep Problems for Climacteric Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 2: 412. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13020412

APA StyleKim, J.-H., & Yu, H.-J. (2024). The Effectiveness of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy on Depression and Sleep Problems for Climacteric Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(2), 412. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13020412