Dermoscopy for the Differentiation of Subacute Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus from Other Erythematous Desquamative Dermatoses—Psoriasis, Nummular Eczema, Mycosis Fungoides and Pityriasis Rosea

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Subacute Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus (SCLE)

3.2. Psoriasis

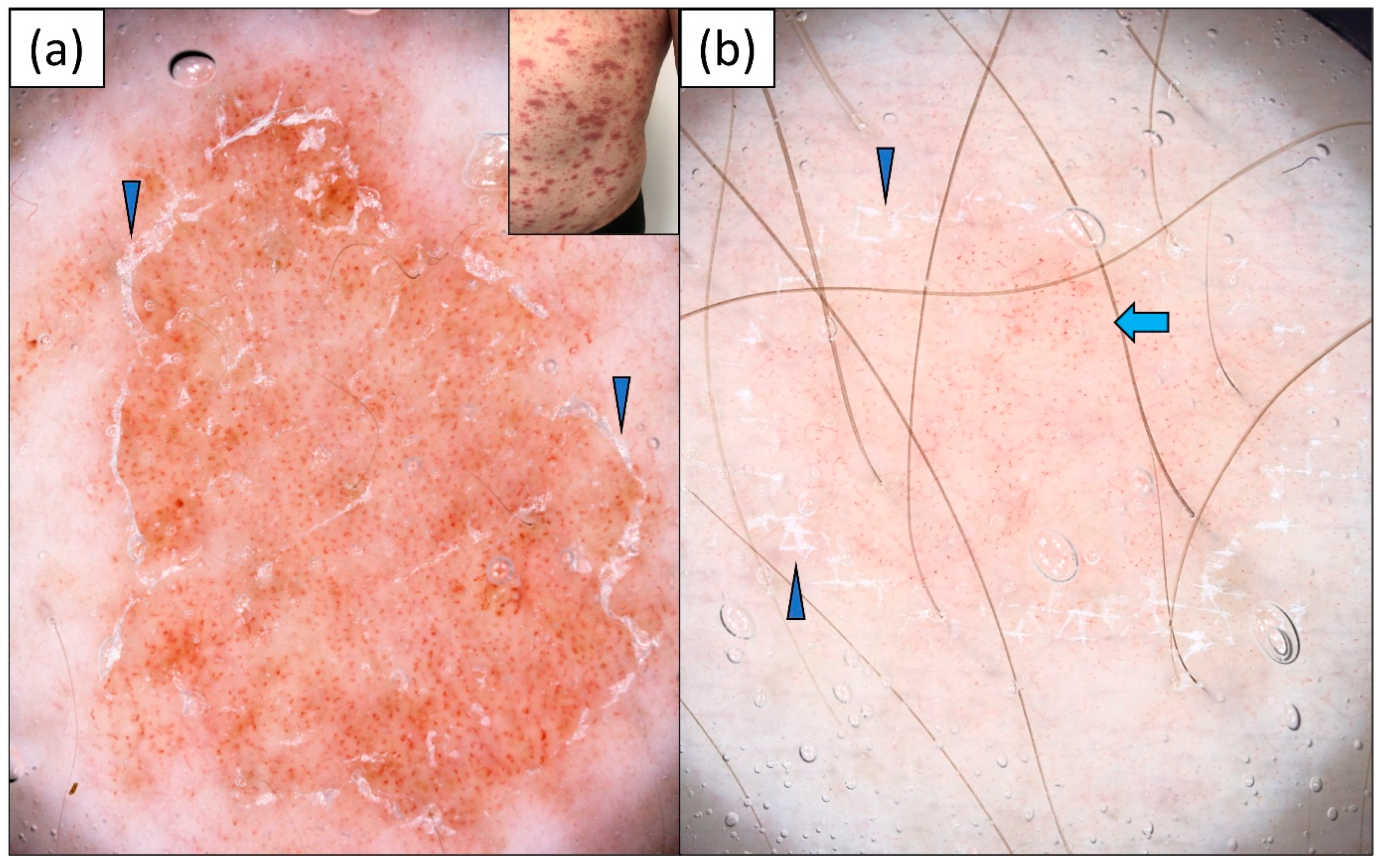

3.3. Nummular Eczema (NM)

3.4. Mycosis Fungoides (MF)

3.5. Pityriasis Rosea

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Errichetti, E.; Stinco, G. Dermoscopy in general dermatology: A practical overview. Dermatol. Ther. 2016, 6, 471–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vale, E.C.S.D.; Garcia, L.C. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: A review of etiopathogenesis, clinical, diagnostic and therapeutic aspects. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2023, 98, 355–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filotico, R.; Mastrandrea, V. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: Clinic-pathologic correlation. G Ital. Dermatol. Venereol. 2018, 153, 216–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borucki, R.; Werth, V.P. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus induced by drugs—Novel insights. Expert. Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2020, 13, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stavropoulos, P.G.; Goules, A.V.; Avgerinou, G.; Katsambas, A.D. Pathogenesis of subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2008, 22, 1281–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meller, S.; Winterberg, F.; Gilliet, M.; Müller, A.; Lauceviciute, I.; Rieker, J.; Neumann, N.J.; Kubitza, R.; Gombert, M.; Bünemann, E.; et al. Ultraviolet radiation-induced injury, chemokines, and leukocyte recruitment: An amplification cycle triggering cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2005, 52, 1504–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangert, J.L.; Freeman, R.G.; Sontheimer, R.D.; Gilliam, J.N. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus and discoid lupus erythematosus. Comparative histopathologic findings. Arch. Dermatol. 1984, 120, 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilliam, J.N.; Sontheimer, R.D. Distinctive cutaneous subsets in the spectrum of lupus erythematosus. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1981, 4, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Errichetti, E.; Piccirillo, A.; Viola, L.; Stinco, G. Dermoscopy of subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Int. J. Dermatol. 2016, 55, e605–e607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzilli, S.; Vollono, L.; Diluvio, L.; Botti, E.; Costanza, G.; Campione, E.; Donati, M.; Prete, M.D.; Orlandi, A.; Bianchi, L.; et al. The combined role of clinical, reflectance confocal microscopy and dermoscopy applied to chronić discoid cutaneous lupus and subacute lupus erythematosus: A case series and literature review. Lupus 2021, 30, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, B.; Kumari, R.; Gochhait, D.; Ayyanar, P. Dermoscopic appearance of an annular subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Dermatol. Pract. Concept. 2021, 11, e2021013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behera, B.; Nayak, A.K.; Dash, S.; Sethy, M. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus: Diagnosis and follow-up by dermoscopy. Indian. Dermatol. Online J. 2021, 12, 755–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montero-Menárguez, J.; Gutiérrez-Collar, C.; Puerta-Peña, M.; Mitsunaga, K.; Peralto, J.L.R.; Velasco-Tamariz, V. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus induced by capecitabine: Confocal microscopy and dermoscopy findings. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 35, e15705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Żychowska, M.; Reich, A. Dermoscopic features of acute, subacute, chronic and intermittent subtypes of cutaneous lupus erythematosus in Caucasians. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 4088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apalla, Z.; Papadimitriou, I.; Iordanidis, D.; Errichetti, E.; Kyrgidis, A.; Rakowska, A.; Sotiriou, E.; Vakirlis, E.; Bakirtzi, A.; Liopyris, K.; et al. The dermoscopic spectrum of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: A retrospective analysis by clinical subtype with clinicopathological correlation. Dermatol. Ther. 2020, 33, e14514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Errichetti, E.; Zalaudek, I.; Kittler, H.; Apalla, Z.; Argenziano, G.; Bakos, R.; Blum, A.; Braun, R.P.; Ioannides, D.; Lacarrubba, F.; et al. Standarization of dermoscopic terminology and basic dermoscopic parameters to evaluate in general dermatology (non-neoplastic dermatoses): An expert consensus on behalf of the International Dermoscopy Society. Br. J. Dermatol. 2020, 182, 454–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żychowska, M.; Łudzik, J.; Witkowski, A.; Lee, C.; Reich, A. Dermoscopy of Gottron’s papules and other inflammatory dermatoses involving the dorsa of the hands. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2022, 36, 1080–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golińska, J.; Sar-Pomian, M.; Rudnicka, L. Dermoscopy of plaque psoriasis differs with plaque location, its duration, and patient’s sex. Skin. Res. Technol. 2021, 27, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgic, S.A.; Cicek, D.; Demir, B. Dermoscopy in differential diagnosis of inflammatory dermatoses and mycosis fungoides. Int. J. Dermatol. 2020, 59, 843–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golińska, J.; Sar-Pomian, M.; Rudnicka, L. Dermoscopic features of psoriasis of the skin, scalp and nails—A systematic review. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2019, 33, 648–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhu, Q.; Li, F.; Xiao, M.; Liu, J. Clinical, dermoscopic, and ultrasonic monitoring of the response to biologic treatment in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1162873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, P.; Meena, D.; Jindal, R.; Roy, S.; Shirazi, N. Dermoscopy in the diagnosis of palmoplantar eczema and palmoplantar psoriasis: A cross-sectional, comparative study from a tertiary care centre in North India. Indian. J. Dermatol. 2023, 68, 120. [Google Scholar]

- Errichetti, E.; Apalla, Z.; Geller, S.; Sławińska, M.; Kyrgidis, A.; Kaminska-Winciorek, G.; Jurakic Toncic, R.; Bobos, M.; Rados, J.; Ledic Drvar, D.; et al. Dermoscopic spectrum of mycosis fungoides: A retrospective observational study by the International Dermoscopy Society. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2022, 36, 1045–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasimi, M.; Bonabiyan, M.; Lajevardi, V.; Azizpour, A.; Nejat, A.; Dasdar, S.; Kianfar, N. Pigmented purpuric dermatoses versus purpuric mycosis fungoides: Clinicopathologic similarities and new insights into dermoscopic features. Australas. J. Dermatol. 2022, 63, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golinska, J.; Sar-Pomian, M.; Slawinska, M.; Sobjanek, M.; Sokołowska-Wojdyło, M.; Rudnicka, L. Trichoscopy may enhance the differential diagnosis of erythroderma. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2022, 47, 394–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, M.; Huerta, T.; Williams, K.; Hristov, A.C.; Tejasvi, T. Dermoscopic features of mycosis fungoides and its variants in patients with skin of color: A retrospective analysis. Dermatol. Pract. Concept. 2021, 11, e2021048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lallas, A.; Apalla, Z.; Lefaki, I.; Sotiriou, E.; Lazaridou, E.; Ioannides, D.; Tiodorovic-Zivkovic, D.; Sidiropoulos, T.; Konstantinou, D.; Di Lernia, V.; et al. Dermoscopy of discoid lupus erythematosus. Br. J. Dermatol. 2013, 168, 284–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żychowska, M.; Żychowska, M. Dermoscopy of discoid lupus erythematosus—A systematic review of the literature. Int. J. Dermatol. 2021, 60, 818–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miteva, M.; Tosti, A. Dermoscopy guided scalp biopsy in cicatricial alopecia. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2013, 27, 1299–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Clinical Characteristics | Diagnosis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCLE n = 27 | Psoriasis n = 36 | Nummular Eczema n = 30 | MF n = 26 | Pityriasis Rosea n = 20 | |

| Sex, n (%) | |||||

| Male | 12 | 20 | 21 | 14 | 17 |

| Female | 15 | 16 | 9 | 12 | 3 |

| Age, years | |||||

| Mean ± SD | 65.2 ± 12.3 | 49.1 ± 19.2 | 42.5 ± 17.8 | 69.5 ± 11.7 | 49.1 ± 11.9 |

| Median (range) | 71.0 | 49.0 | 42.5 | 71.0 | 50.0 |

| Fitzpatrick skin phototype, n (%) | |||||

| I | 10 | 8 | 5 | 9 | 3 |

| II | 17 | 25 | 21 | 16 | 16 |

| III | 0 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| Dermoscopic Characteristics | SCLE n = 27 | Psoriasis n = 36 | Nummular Eczema n = 30 | MF n = 26 | Pityriasis Rosea n = 20 | p Value | Specificity | PPV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morphology of vessels, n (%) | ||||||||

| Dotted | 16 (59.3) | 36 (100.0) | 30 (100.0) | 23 (88.5) | 19 (95.0) | <0.01 | 3.9% | 12.9% |

| Linear | 25 (92.6) | 1 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (38.5) | 5 (25.0) | <0.01 | 85.7% | 61.0% |

| Linear with branches | 17 (63.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (13.4) | 0 (0.0) | <0.01 | 96.4% | 81.0% |

| Thick | 4 (14.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0.01 | 99.1% | 80.0% |

| Thin | 16 (59.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (13.4) | 0 (0.0) | <0.01 | 96.4% | 80.0% |

| Linear curved | 2 (7.4) | 2 (5.6) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (34.6) | 1 (5.0) | <0.01 | 89.3% | 14.3% |

| Polymorphous | 25 (92.6) | 3 (8.3) | 0 (0.0) | 14 (53.8) | 5 (25.0) | <0.01 | 80.4% | 53.2% |

| Distribution of vessels, n (%) | ||||||||

| Uniform | 0 (0.0) | 26 (72.2) | 2 (6.7) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (45.0) | <0.01 | 67.0% | 0.0% |

| Clustered | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.8) | 2 (6.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.47 | 97.3% | 0.0% |

| Peripheral | 2 (7.4) | 4 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (7.7) | 1 (5.0) | 0.44 | 93.8% | 22.2% |

| Unspecific | 25 (92.6) | 5 (13.9) | 26 (86.7) | 22 (84.6) | 8 (40.0) | <0.01 | 45.5% | 29.1% |

| Ring pattern | 0 (0.0) | 3 (8.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.24 | 97.3% | 0.0% |

| Color of scales, n (%) | ||||||||

| White | 14 (51.9) | 35 (97.2) | 21 (70.0) | 19 (73.1) | 20 (100.0) | <0.01 | 15.2% | 12.8% |

| Yellow | 1 (3.7) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (30.0) | 3 (11.5) | 0 (0.0) | <0.01 | 89.3% | 7.7% |

| Distribution of scales, n (%) | ||||||||

| Diffuse | 1 (3.7) | 10 (27.8) | 8 (26.7) | 7 (26.9) | 0 (0.0) | <0.01 | 77.7% | 3.8% |

| Central | 2 (7.4) | 3 (8.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.19 | 97.3% | 40.0% |

| Peripheral | 4 (14.8) | 14 (38.9) | 3 (10.0) | 5 (19.2) | 14 (70.0) | <0.01 | 67.9% | 10.0% |

| Patchy | 7 (25.9) | 13 (36.1) | 11 (36.7) | 12 (46.2) | 7 (35.0) | 0.67 | 61.6% | 14.0% |

| Along skin lines | 0 (0.0) | 4 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.8) | 4 (20.0) | 0.01 | 92.0% | 0.0% |

| Follicular findings, n (%) | ||||||||

| Follicular plugs | 5 (18.5) | 1 (2.8) | 1 (3.3) | 2 (7.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.08 | 96.4% | 55.6% |

| Perifollicular white halo | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (7.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.28 | 98.2% | 0.0% |

| Perifollicular scaling | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.8) | 2 (10.0) | 0.04 | 97.3% | 0.0% |

| Morphologies/colors, n (%) | ||||||||

| White structureless areas | 1 (3.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (13.4) | 0 (0.0) | <0.01 | 96.4% | 20.0% |

| Pink structureless areas | 4 (14.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.3) | 6 (23.1) | 0 (0.0) | <0.01 | 93.8% | 36.4% |

| Yellow structureless areas | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.8) | 9 (30.0) | 5 (19.2) | 0 (0.0) | <0.01 | 86.6% | 0.0% |

| Orange structureless areas | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.8) | 1 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1.00 | 98.2% | 0.0% |

| Dots/globules | 10 (37.0) | 14 (38.9) | 22 (73.3) | 14 (53.8) | 7 (35.0) | 0.02 | 49.1% | 14.9% |

| Red dots | 1 (3.7) | 12 (33.3) | 16 (53.3) | 9 (34.6) | 6 (30.0) | <0.01 | 61.6% | 2.3% |

| Red globules | 1 (3.7) | 8 (22.2) | 5 (16.7) | 7 (26.9) | 2 (10.0) | 0.13 | 80.4% | 4.3% |

| Gray-brown dots | 10 (37.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (13.4) | 1 (5.0) | <0.01 | 95.5% | 66.7% |

| Gray-brown globules | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0.33 | 99.1% | 0.0% |

| White-yellowish globules | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.8) | 1 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1.00 | 98.2% | 0.0% |

| White lines | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0.33 | 99.1% | 0.0% |

| Circles | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0.33 | 99.1% | 0.0% |

| Specific clues, n (%) | ||||||||

| Yellowish crust | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (6.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.14 | 98.2% | 0.0% |

| Erosion | 1 (3.7) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (13.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.03 | 96.4% | 20.0% |

| “Sticky fiber” sign | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (23.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | <0.01 | 93.8% | 0.0% |

| Dull pink background | 6 (22.2) | 6 (16.7) | 18 (60.0) | 15 (57.7) | 6 (30.0) | <0.01 | 59.8% | 11.8% |

| Pink-red background | 20 (74.1) | 30 (83.3) | 12 (40.0) | 11 (42.3) | 13 (65.0) | <0.01 | 41.7% | 23.3% |

| Red hemorrhagic areas | 2 (7.4) | 6 (16.7) | 6 (20.0) | 6 (23.1) | 1 (5.0) | 0.33 | 83.0% | 9.5% |

| Pigmentation | 15 (55.6) | 2 (5.6) | 5 (16.7) | 9 (34.6) | 1 (5.0) | <0.01 | 84.8% | 46.9% |

| Peripheral pigmentation | 7 (25.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | <0.01 | 99.1% | 87.5% |

| Yellow-orange round structures | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.3) | 1 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0.60 | 98.2% | 0.0% |

| White follicular dots | 2 (7.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.09 | 100.0% | 100.0% |

| Stellate brown structures | 3 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.02 | 100.0% | 100.0% |

| Author, Year | Type of Study | Number of Cases | Type of Dermatoscope, Magnification | Main Dermoscopic Findings | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vessels | Scales | Follicular Findings | Morphologies/Colors | Remarks | |||||

| Color | Distribution | ||||||||

| Errichetti et al., 2016 [9] | Case series | 9 | Handheld DermLite DL3, ×10 | Linear (4/9) Linear irregular (6/9) Sparsely distributed dotted (8/9) Branched (3/9) | White (100%; 9/9) | Peripheral (5/9) Diffuse (4/9) | Focal orange-yellowish structureless areas (3/9) | ||

| Apalla et al., 2020 [15] | Original | 30 | DermLite Photosystem, ×10 | Linear curved (10/30) Dotted (10/30) Linear branched (5/30) Linear (2/30) | White (21/30) Yellow-brown (11/30) | Patchy (16/30) Diffuse (5/30) | Follicular plugs/rosettes (11/30) Perifollicular white halo (7/30) | Erythema (26/30) Pink structureless areas (26/30) White structureless areas (14/30) Orange structureless areas (9/30) Brown structureless areas (1/30) Gray-brown dots (2/30) Erosion (7/30) | |

| Behera et al., 2021 [12] | Case report | 1 | DermLite DL4, ×10 | Linear (1/1) Linear curved/comma (1/1) Focal dotted (1/1) | White (1/1) | Patchy (1/1) Diffuse (1/1) | Follicular plugs (1/1) | White structureless area (1/1) White shiny structures (1/1) Focal multicolored pattern (1/1) Brown to blue-gray peppering (1/1) | Treatment follow-up by dermoscopy |

| Behera et al., 2021 [11] | Case report | 1 | Heine Delta 20, ×10 | Linear (1/1) Hairpin (1/1) Glomerular (1/1) | White (1/1) | N/A | none | White to reddish-white homogenous area (1/1) Brown to blue-gray dots (1/1) Blue-gray peppering (1/1) White homogenous area around blood vessel (1/1) | |

| Mazzilli et al., 2021 [10] | Case series | 2 | N/A | Mixed vascular pattern (2/2) | White (1/1) | Diffuse (1/1) | none | ”pigment areas” (1/1) Focal yellowish areas (1/1) | Additional report of confocal findings |

| Montero-Menarguez et al., 2022 [13] | Case report | 1 | N/A | Thin arborizing (1/1) | White (1/1) | N/A | Big yellow dots (1/1) | Erythema (1/1) | Additional report of confocal findings |

| Żychowska et al., 2022 [14] | Original | 11 | Canfield D200EVO videodermatoscope (×20–70) | Linear (8/11) Linear branched (8/11) Linear curved (8/11) Dotted (7/11) | White (7/11) Yellow (1/11) | Patchy (8/11) Peripheral (1/11) | Follicular plugs (2/11) | Pink-red background (10/11) Peripheral pigmentation (5/11) Red hemorrhagic areas (4/11) Dilated follicles (3/11) Gray-brown dots (2/11) Erosion (2/11) White-yellowish globules (1/11) Pink structureless areas (1/11) ”sticky fiber” sign (1/11) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Żychowska, M.; Kołcz, K. Dermoscopy for the Differentiation of Subacute Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus from Other Erythematous Desquamative Dermatoses—Psoriasis, Nummular Eczema, Mycosis Fungoides and Pityriasis Rosea. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 577. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13020577

Żychowska M, Kołcz K. Dermoscopy for the Differentiation of Subacute Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus from Other Erythematous Desquamative Dermatoses—Psoriasis, Nummular Eczema, Mycosis Fungoides and Pityriasis Rosea. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(2):577. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13020577

Chicago/Turabian StyleŻychowska, Magdalena, and Kinga Kołcz. 2024. "Dermoscopy for the Differentiation of Subacute Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus from Other Erythematous Desquamative Dermatoses—Psoriasis, Nummular Eczema, Mycosis Fungoides and Pityriasis Rosea" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 2: 577. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13020577

APA StyleŻychowska, M., & Kołcz, K. (2024). Dermoscopy for the Differentiation of Subacute Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus from Other Erythematous Desquamative Dermatoses—Psoriasis, Nummular Eczema, Mycosis Fungoides and Pityriasis Rosea. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(2), 577. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13020577