Abstract

Background: The wave of wartime migration from Ukraine has raised a number of concerns about infectious diseases, the prevalence of which is higher in Ukraine than in host countries, with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection being one of them. Our analysis aimed to assess the percentage of HCV-infected Ukrainian refugees under care in Polish centers providing antiviral diagnosis and therapy, to evaluate their characteristics and the effectiveness of treatment with direct-acting antiviral drugs (DAAs). Methods: The analysis included patients of Polish and Ukrainian nationality treated for HCV infection between 2022 and 2024 in Polish hepatology centers. Data were collected retrospectively and completed online. Results: In the population of 3911 patients with chronic hepatitis C treated with DAAs in 16 Polish centers in 2022–2024, there were 429 war refugees from Ukraine, accounting for 11% of the total treated. The Ukrainian population was significantly younger (45.7 vs. 51 years, p < 0.001) and had a higher percentage of women (50.3% vs. 45.3%, p = 0.048) compared to Polish patients. Patients of Ukrainian origin had less advanced liver disease and were significantly less likely to have comorbidities and the need for comedications. Coinfection with human immunodeficiency virus was significantly more common in Ukrainians than in Polish patients, 16.1% vs. 5.9% (p < 0.001). The distribution of HCV genotypes (GTs) also differed; although GT1b predominated in both populations, its frequency was significantly higher in the Polish population (62.3% vs. 44.5%, p < 0.001), while the second most common GT3 was significantly more common in Ukrainian patients (30.5% vs. 16.2%, p < 0.001). Conclusions: Documented differences in patient characteristics did not affect the effectiveness of antiviral therapy, which exceeded 97% in both populations, but there was a higher rate of those lost to follow-up among Ukrainian patients.

1. Introduction

Russian aggression against Ukraine has caused the largest migration crisis in Europe since World War II. Millions of Ukrainian citizens have been forced to leave their homeland in search of safety in other European countries. Among the countries where the largest number of war refugees have arrived was Poland. According to estimates by the border guards, several million Ukrainians have entered the country since the beginning of the war. For some of them, it was a transit point on their onward journey; some decided to return to their homeland; and for about a million, Poland became the final destination. Importantly, along with the people came their health problems and diseases they suffer from, of which infectious illnesses have a significant share. Differences in the prevalence of certain communicable diseases in Ukraine and Poland have influenced their epidemiology in our country, especially with regard to infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), tuberculosis, sexually transmitted diseases, and hepatitis C [1,2].

Based on available data, Ukraine has one of the highest prevalences of HCV infection in the world, with 3.1% of viremic cases, corresponding to about 1,300,000 infected patients [3,4]. In high-risk populations, it is even much higher exceeding 60% among drug users [4,5]. However, according to the Ministry of Health of Ukraine and patient organizations, the actual incidence is much higher than the official rate, reaching 5%, and only 7% of infected people are aware of the disease and receive the necessary specialized healthcare [6,7]. In November 2019, Ukraine joined the global strategy of the World Health Organization (WHO) to eliminate hepatotropic virus infections as a public health threat by adopting a national strategy to combat viral hepatitis [8]. As a result of taking up this challenge, 230 healthcare institutions have contracted state-funded antiviral treatment free of charge to patients [9]. These facilities provided about 16,000 thousand therapies annually, which did not meet the need [9]. The situation was significantly worsened by the Russian aggression against Ukraine, during which, due to war damage and the reorganization of the state budget, there were only 80 facilities left that could provide HCV diagnostics and treatment to about 10,000 patients a year [9]. Reaching medical institutions has become an additional difficulty at a time when survival has become more important than health.

This priority was the reason for a huge wave of refugees, which also included patients infected with HCV, both aware of it and undiagnosed. Addressing this issue, a joint statement from the European Center for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), WHO, and the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) has been issued, reviewing public health guidelines aimed at ensuring that the needs of refugees with viral hepatitis are adequately met across the continuum of care, from prevention to treatment in host countries [10]. In Poland, thanks to a special law on assistance to Ukrainian citizens in connection with the armed conflict that grants the right to health services to war refugees from Ukraine on the same terms as insured citizens of Poland, they have gained access to diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic diseases, including HCV infection [11].

The aim of our analysis was to assess the percentage of Ukrainians infected with HCV treated in Polish centers providing antiviral diagnostics and therapy to evaluate their characteristics and the effectiveness of treatment with direct-acting antiviral drugs (DAAs) compared to Polish patients.

2. Materials and Methods

This study included patients from the EpiTer-2 database, which is an ongoing, retrospective, multicenter, national study initiated by investigators from the Polish Association of Epidemiologists and Infectious Disease Physicians, conducted in real-world experience conditions, assessing antiviral treatment in 19,441 patients with chronic hepatitis C treated in 22 Polish hepatology centers between 2015 and 2024. The current analysis included 3911 patients from 16 centers that were able to determine the Polish or Ukrainian nationality of patients treated for HCV infection between 2022 and 2024.

The type of antiviral treatment used was selected by the attending physician based on current national recommendations [12] and the reimbursement policy of the National Health Fund (NFZ). Doses and duration of treatment were prescribed in accordance with the Summary of Product Characteristics of the individual drugs.

All patients gave informed consent before starting treatment according to the requirements of the National Health Fund. Clinical and laboratory data were collected retrospectively and sent via an online platform operated by Tiba sp. z o.o. (Wrocław, Poland) in line with the national regulations on protecting personal data in Poland. The originally collected data were used to monitor the effectiveness and safety of registered drugs in real clinical conditions under the requirements of the National Health Fund and were not intended for scientific purposes. Patients were not subjected to any experimental procedures or therapies, which meant that the EpiTer-2 program was non-interventional and, according to the law in effect at the time of its implementation, did not require ethics committee approval.

Baseline data included age, sex, body mass index (BMI), comorbidities and concomitant medications, assessment of liver disease severity, hepatitis B virus (HBV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) coinfection, and history of previous antiviral therapy. Liver disease severity was assessed by transient elastography (TE) performed with a FibroScan device (Echosens, Paris, France), shear wave elastography (SWE) using the Aixplorer system (SuperSonic Imagine, Aix-en-Provence, France), or liver biopsy. Results were standardized to the METAVIR score (F0–F4) using the EASL recommendations. Patients with cirrhosis were assessed using the Child–Pugh (CP) and Model for End-of-Life Liver Disease (MELD) scores. HCV RNA was assessed by real-time polymerase chain reaction assays with a lower limit of detection at 15 IU/mL. Effectiveness assessment was performed 12 weeks after the end of treatment using an intent-to-treat (ITT) analysis, including patients who received at least one dose of antiviral therapy, and a per-protocol (PP) analysis, including only patients who were not lost to follow-up.

The results were expressed as mean with standard deviation or absolute number objectified by percentage values. Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad (Prism Software, Prism 10, Irvine, CA, USA). The data were assessed for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test, and then comparative analysis between groups was carried out by Mann–Whitney U test for continuous data and chi-square for categorical data. The differences were considered statistically significant if p < 0.05.

3. Results

Of the 3911 individuals included in this study, 429 (11%) were patients of Ukrainian origin. As can be seen from Table 1, the highest percentage of patients of Ukrainian origin among all treated patients, even above 20%, was recorded in centers located in northern (Szczecin, Gdańsk) and southern Poland (Kraków, Wrocław, Chorzów, Myślenice), while the lowest, below 3%, was in the eastern part of the country (Białystok, Lublin).

Table 1.

Distribution of Ukrainian patients in the treating centers.

In contrast to Polish patients, the Ukrainian population was significantly younger (45.7 years vs. 51 years, p < 0.001) and had a higher proportion of females (50.3% vs. 45.3%, p = 0.048). No significant differences were observed in BMI, and the percentages of patients who did not respond to previous treatment were similar (Table 2).

Table 2.

Patients characteristics.

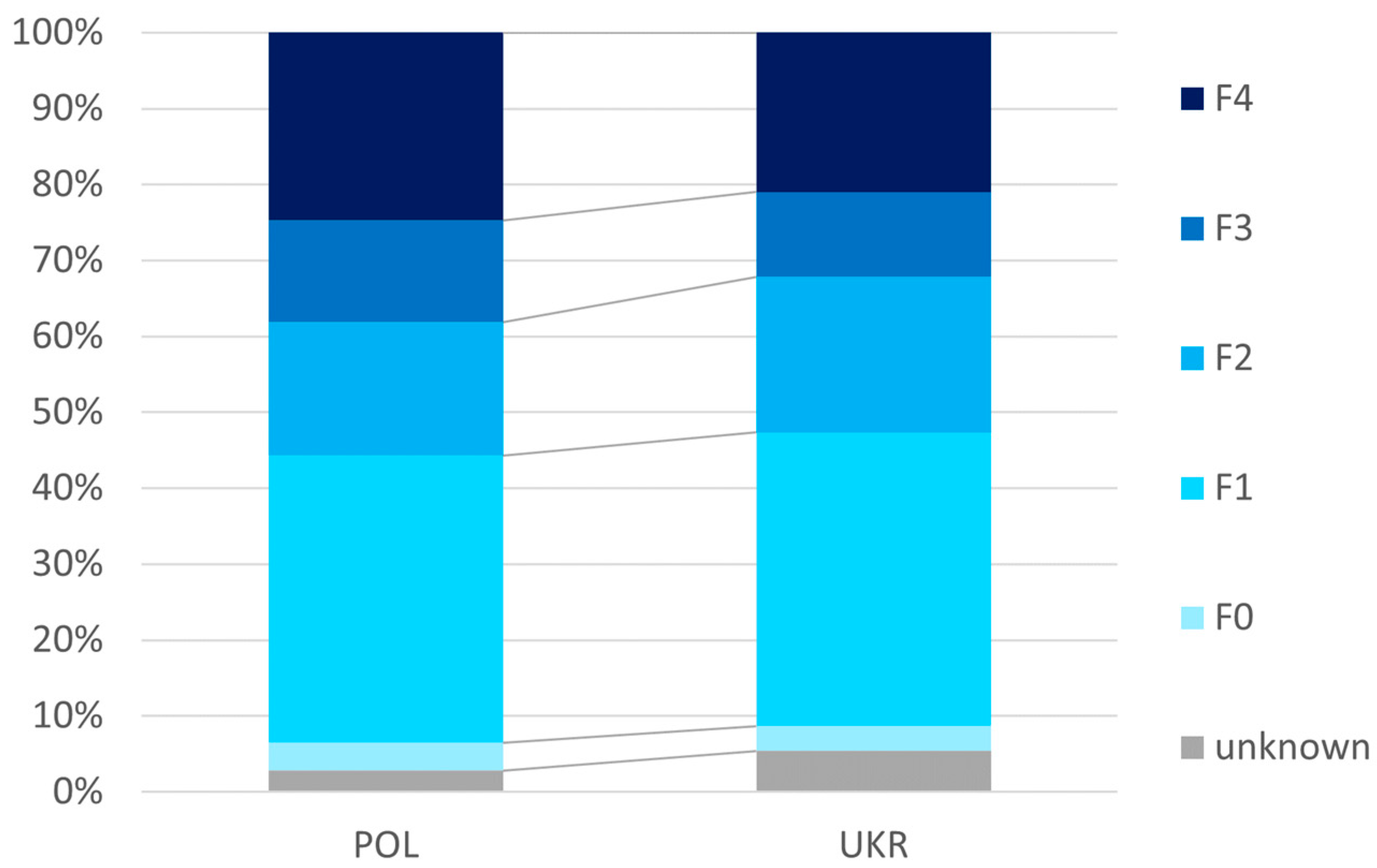

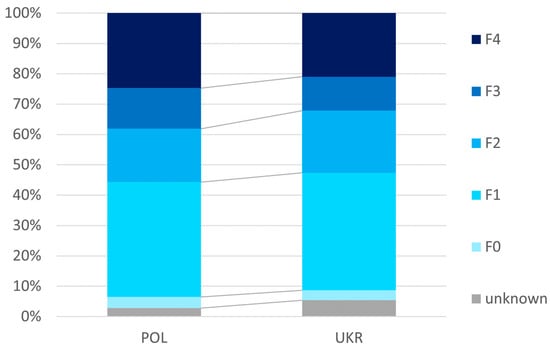

As shown in Figure 1, the Ukrainian population was characterized by less advanced liver disease, as expressed by a significantly (p = 0.017) lower percentage of cumulative patients with F3 or F4 (32.2% vs. 38.1%), as well as significantly lower mean values of liver tissue stiffness assessed by elastography (10.3 ± 9.7 vs. 12.0 ± 11.4 kPa) and MELD score (7.6 ± 2.5 vs. 7.8 ± 2.5) (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Advancement of liver disease.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the HCV infection and liver disease.

As can be seen from Table 2 and Table 3, patients of Ukrainian origin had significantly less frequent comorbidities and required additional medications and less frequently had a history of hepatocellular carcinoma and decompensation in the past, as well as the presence of esophageal varices or ascites at the time of starting therapy. HIV coinfection was reported significantly more often in the Ukrainian population, while the incidence of HBV coinfection was comparable (Table 2).

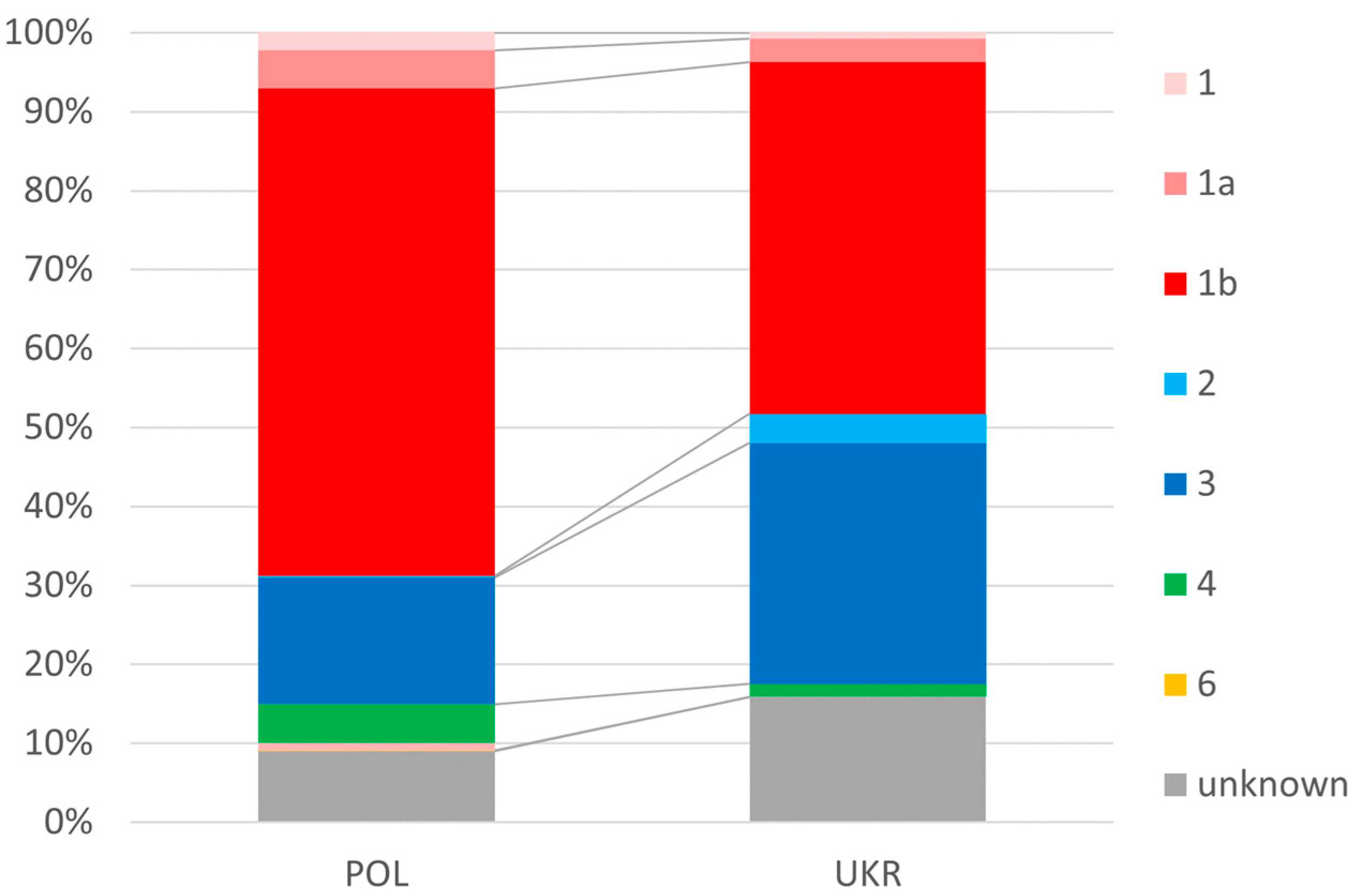

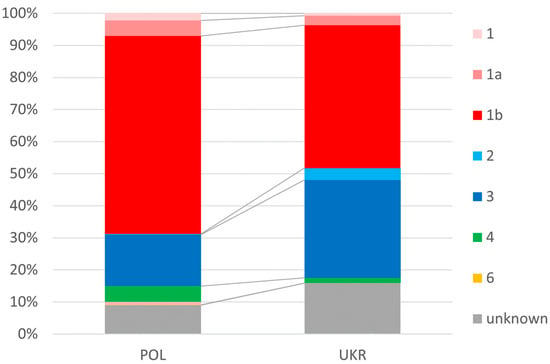

In the Ukrainian population of patients, infections with genotypes 2 and 3 occurred significantly more frequently than in the Polish population (34.2% vs. 21.1%), and genotype 1 was less frequent (48.2% vs. 69.4%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Prevalence of genotypes.

As can be seen from Table 3, the values of laboratory parameters analyzed before the start of treatment demonstrated some statistically significant differences, including higher ALT activity (97.1 vs. 88.7 IU/L, p = 0.02), higher albumin concentration (4.3 vs. 4.2 g/dL, p = 0.001), and lower bilirubin concentration (0.74 vs. 0.81 mg/dL, p = 0.01) in Ukrainians as compared to Polish patients.

Regardless of nationality, patients received similar types of therapy, with glecaprevir/pibrentasvir being the most common (Table 4).

Table 4.

Therapy and its effectiveness.

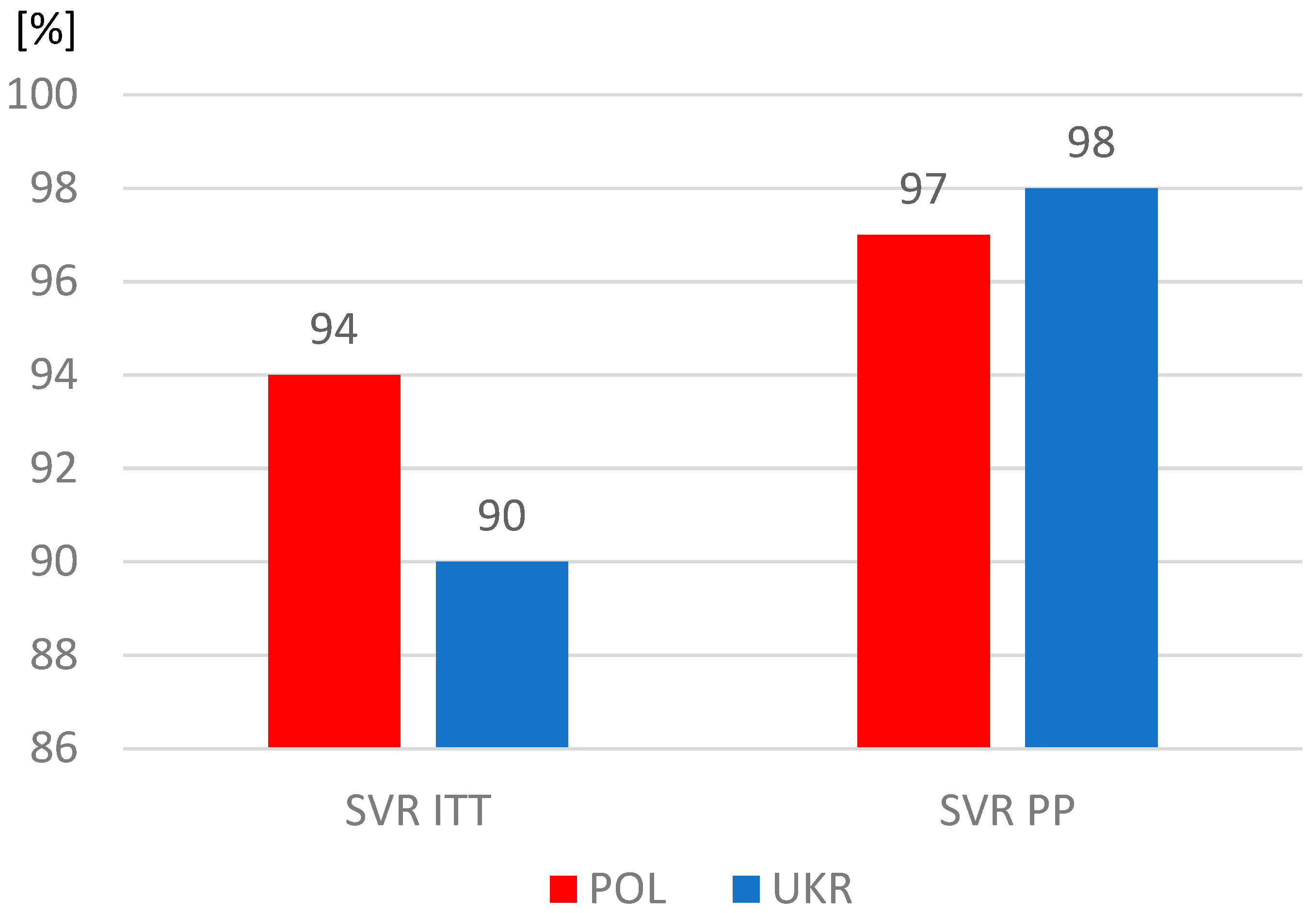

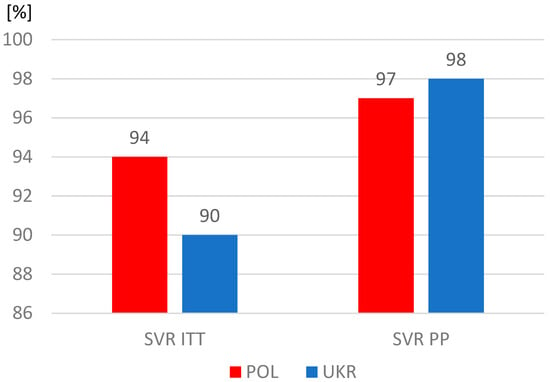

The proportions of patients who completed therapy according to plan were similar, but significantly more often patients from Ukraine did not report for a visit assessing the effectiveness of therapy and were considered lost to follow-up. As a result, the sustained virologic response (SVR) rate among Ukrainians was significantly lower in the intent-to-treat analysis, which included all patients who started treatment, including those lost to follow-up (Table 4). However, after excluding this group, the SVR values calculated per protocol exceeded 97% and were similar in both study populations (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Sustained virologic response (SVR); ITT, intent-to-treat analysis; PP, per protocol analysis.

4. Discussion

The wave of war refugees from Ukraine flowing widely through many European countries has raised a number of concerns about the transmission of infectious diseases, the incidence of which has been higher in Ukraine than in host countries [13,14]. The insufficient level of vaccination against many communicable diseases in Ukraine and the sanitary conditions in which refugees traveled and stayed led to the list of concerns starting with acute vaccine-preventable diseases, such as measles, rubella, whooping cough, diphtheria, polio, hepatitis B (HBV) and tuberculosis [15,16,17]. However, the wave of migration also carried the risk of infections that cannot be prevented by vaccines and whose incidence in Ukraine was significantly higher than in the host countries, including sexually transmitted diseases, HIV, and HCV infection [18,19]. Awareness of this risk was reflected in the joint position of WHO, ECDC, and EASL, whose goal was to provide the necessary diagnostic and therapeutic care to refugees with hepatotropic virus infections [10]. Solutions regulating medical care in host countries were designed in different ways; in Poland, people from Ukraine were provided with free medical care on the basis of the so-called special law that made diagnosis and therapy possible for such patients [13].

Testing of Ukrainian refugees in Poland for the presence of anti-HCV antibodies is carried out on a voluntary basis. HCV infection diagnostic and treatment centers receive both newly diagnosed patients and those who were previously aware of the infection, but due to limited access to DAA therapy in Ukraine, have not yet started treatment. In practice, medical care focuses on qualification for therapy and antiviral treatment, while cases of continuation of DAA administration started in Ukraine seem to be marginal due to the short duration of treatment.

The subjects of our analysis, which covered 15 Polish cities, were refugees from Ukraine with chronic hepatitis C undergoing antiviral therapy with DAAs. They accounted for a total of 11% of all those receiving antiviral treatment for HCV infection in these centers, noting that the spread of their share from center to center was very large, ranging from less than 3 to more than 21%. The highest percentage of Ukrainian patients was reported in large hepatology centers in the north and south of Poland, in cities with high potential for residence and employment. Not insignificant for some of these centers seems to be the location near Poland’s western border with Germany, which is a further destination for many refugees from Ukraine [20]. Although the largest Ukrainian population resides in Warsaw and the Mazovia province, the percentage of Ukrainians treated with DAAs in these areas was just over 11%, perhaps because our analysis did not include all the centers located in this area. The lowest percentage of Ukrainian patients were treated in hepatology centers in eastern Poland, which seems to be the least attractive for refugees in terms of residence and profitable work.

Nevertheless, based on these data, the increase in demand for DAA therapy in Polish centers caused by the wave of migration from Ukraine did not reach the scale as predicted, taking into account the several-fold difference in the prevalence of HCV. One of the possible reasons can be refugees’ fears of discrimination against infected people, social stigmatization in a new living environment, and the risk of losing their jobs; the language barrier also matters [21]. Fear of discrimination in the community and workplace was particularly pronounced for individuals with HIV. Although a significantly higher rate of HIV/HCV coinfection was documented in our study among Ukrainian refugees compared to Polish patients treated with DAAs, the difference was not as high as one would expect based on available data [19]. The main route of HCV transmission in Ukraine is intravenous drug use, and among the estimated 340,000 PWID (people who inject drugs) in Ukraine, the prevalence of HCV exceeds 50%, which is even higher in selected cities such as Kyiv with 84.8%; more than half of the cases involve coinfection with HIV, while in our analysis, they accounted for only 16% compared to 6% in the Polish patient group [19,22]. However, the incidence of HBV coinfection was comparable in both nations, amounting to less than 1%, and in the case of Polish patients, it was consistent with previously published data [23]. In the case of Ukraine, only data on the population prevalence of HBsAg obtained by modeling are available, reporting a value of 1% [24].

When comparing the HCV-infected populations from both countries, we noticed differences in the age of treated patients; individuals from Ukraine were significantly younger than those from Poland. It is difficult to comment on these data, as there is a lack of analyses describing HCV-infected patients in Ukraine; data from a single publication on a population of 868 patients, mostly PWID (87%), 55% of whom were coinfected with HIV, report a mean age of 39 years at the start of DAA treatment [25]. The latest published Polish data indicate that the largest percentage of patients diagnosed with HCV infection, which in practice equates to almost simultaneous qualification for therapy and immediate initiation of treatment, is in the 45–64 age range [26].

The lower age of Ukrainian patients should probably be linked to the lower burden of comorbidities and the medications taken for them as compared to the Polish population. The lower age of patients from Ukraine also explains why they were characterized by less advanced liver disease, defined by the percentage of individuals with advanced liver fibrosis and cirrhosis and a lower share of those with decompensation of liver function, both in history and at the start of therapy. A smaller percentage of refugees had a history of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and documented esophageal varices. Less advanced liver disease in the refugee population also explains the significant differences in laboratory parameters, such as albumin and bilirubin levels.

The phenomenon of less severe liver disease may have been influenced not only by the lower age of Ukrainian patients but also by difficulties in reaching healthcare facilities for older refugees, for whom the language and information barrier is greater than in the case of younger people [21].

Another significant difference that we reported in our analysis concerned the gender distribution of infected patients. The Polish population was dominated by men, constituting 55%, and among patients from Ukraine, women predominated, with a 50.3% share. While we expected a predominance of women in the Ukrainian population, its small scale was a surprise to us, considering that approximately 80% of war refugees from Ukraine are women [27]. One of the possible explanations for this disproportion is that the domination of women among refugees was offset by the significant predominance of men with chronic hepatitis C; according to available data, they constitute more than 60% of all HCV-infected people in Ukraine [25,28].

In contrast, we were not surprised by the differences in the distribution of HCV genotypes documented in our study. In both populations, genotype 1 (GT1) dominated, but the dominance was more pronounced in the Polish population, with almost 70% compared to 48% in Ukrainians. This order and the smaller difference between GT1 and the second most common GT3 in the Ukrainian population compared to Polish patients are consistent with published data [28,29,30].

The differences identified in our analysis in the characteristics of the populations of Polish and Ukrainian patients with HCV infection did not translate into treatment effectiveness, which exceeded 97% in both groups. It should be noted, however, that with a comparable percentage of people completing therapy as planned, the percentage of patients lost to follow-up among Ukrainian refugees was twice as high as that in the Polish group. It seems that this may have been partly due to an unstable life situation, forcing a return to their homeland or further migration. On the other hand, the fact that as many as 92% of patients remained under observation, usually lasting 20 to 24 weeks, means that when starting treatment, they planned to stay longer or permanently in Poland.

Our study has limitations that we have to declare. Some of these are due to the real-world nature and retrospective design of the analysis and involve possible bias, incomplete data, and errors at the database entry stage. The study did not cover all centers treating HCV infection in Poland and thus certainly did not include all war refugees from Ukraine treated in our country. However, the analyzed group was diverse and encompassed different regions of Poland, thus becoming a representative sample, which we consider its strength. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first analysis of DAA therapy in HCV-infected war refugees from Ukraine in the host country. Although our analysis focuses on migrants from Ukraine in Poland, we believe that the findings we obtained may be useful for the elimination of HCV infection in this population in other host countries as well, as the wave of migration from Ukraine sweeps through many European countries.

5. Conclusions

An analysis of nearly 4000 HCV-infected patients treated with DAAs in several centers in various regions of Poland revealed an 11% share of refugees from Ukraine. Patients of Ukrainian origin were younger and had fewer comorbidities and less advanced liver disease compared to Polish patients, but they were significantly more often coinfected with HIV. The described differences in patient characteristics did not affect the effectiveness of antiviral therapy, which exceeded 97% regardless of the origin of the patients, but among Ukrainian patients, there was a higher percentage of people lost to follow-up without SVR assessment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.F. and D.Z.-M.; methodology, R.F. and D.Z.-M.; validation, R.F., D.Z.-M., D.M., J.J.-L., H.B., M.S., W.M., E.J., B.L., J.K., Ł.L., D.D., A.P., M.T.-Z., K.D. and A.P.-K.; formal analysis, D.M.; investigation, D.M.; resources, R.F. and D.Z.-M.; data curation, R.F. and D.Z.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, R.F. and D.Z.-M.; writing—review and editing, K.D.; visualization, D.M.; supervision, R.F.; project administration, R.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to its retrospective nature.

Informed Consent Statement

Due to the retrospective nature of the study, a waiver of consent was in effect.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy reasons.

Acknowledgments

Polish Association of Epidemiologists and Infectiologists.

Conflicts of Interest

Flisiak R has acted as a speaker and/or advisor, and has received funding for clinical research from AbbVie, Gilead, Merck, and Roche. Zarębska-Michaluk D has acted as a speaker for AbbVie and Gilead. Martonik D. has no conflicts of interest to declare. Janocha-Litwin J has no conflicts of interest to declare. Berak H has acted as a speaker and/or advisor for Gilead and Abbvie. Sitko M has acted as a speaker for Gilead and AbbVie. Mazur W has acted as a speaker and/or advisor for AbbVie, Gilead, and Merck, and has received funding for clinical trials from AbbVie, Gilead, and Janssen. Janczewska E has acted as a speaker and/or advisor for AbbVie, Gilead, MSD, and Ipsen, and has received funding for clinical trials from AbbVie, Allergan, BMS, Celgene, Cymabay, Dr Falk Pharma, Exelixis, GSK, and MSD. Lorenc B has no conflicts of interest to declare. Klapaczyński J has acted as a speaker for Gilead and AbbVie. Laurans Ł has no conflicts of interest to declare. Dybowska D has received funding for participation in the conference from Gilead. Piekarska A has acted as a speaker and/or advisor for AbbVie, Gilead, Merck, and Roche. Tudrujek-Zdunek M has no conflicts of interest to declare. Dobrowolska K has no conflicts of interest to declare. Parfieniuk-Kowerda A has no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Meldunki Epidemiologiczne. Available online: https://www.pzh.gov.pl/serwisy-tematyczne/meldunki-epidemiologiczne/ (accessed on 14 August 2024).

- Rzymski, P.; Zarębska-Michaluk, D.; Parczewski, M.; Genowska, A.; Poniedziałek, B.; Strukcinskiene, B.; Moniuszko-Malinowska, A.; Flisiak, R. The Burden of Infectious Diseases throughout and after the COVID-19 Pandemic (2020–2023) and Russo-Ukrainian War Migration. J. Med. Virol. 2024, 96, e29651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blach, S. Global Change in Hepatitis C Virus Prevalence and Cascade of Care between 2015 and 2020: A Modelling Study. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 7, 396–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yakovleva, A.; Kovalenko, G.; Redlinger, M.; Smyrnov, P.; Tymets, O.; Korobchuk, A.; Kotlyk, L.; Kolodiazieva, A.; Podolina, A.; Cherniavska, S.; et al. Hepatitis C Virus in People with Experience of Injection Drug Use Following Their Displacement to Southern Ukraine before 2020. BMC Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iakunchykova, O.; Meteliuk, A.; Zelenev, A.; Mazhnaya, A.; Tracy, M.; Altice, F.L. Hepatitis C Virus Status Awareness and Test Results Confirmation among People Who Inject Drugs in Ukraine. Int. J. Drug Policy 2018, 57, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukrinform Лише 7% Хвoрих На Гепатит С Знають Прo Свoю Недугу—Сумна Статистика МОЗ. Available online: https://www.ukrinform.ua/rubric-society/3288355-lise-7-hvorih-na-gepatit-s-znaut-pro-svou-nedugu-sumna-statistika-moz.html (accessed on 14 August 2024).

- Romanivna, M.S.; Olechivna, G.O.; Yaroslavovich, S.D. Incidence and Prevalence of Hepatitis C in Ukraine and the World. Colloq. J. 2023, 8, 30–31. [Google Scholar]

- Devi, S. Ukrainian Health Authorities Adopt Hepatitis C Project. Lancet 2020, 396, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.euractiv.com/section/health-consumers/news/how-war-in-ukraine-created-new-risks-for-viral-hepatitis-infections/ (accessed on 14 August 2024).

- Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/WHO-ECDC-EASL-statement.pdf (accessed on 14 August 2024).

- Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20220000583 (accessed on 14 August 2024).

- Tomasiewicz, K.; Flisiak, R.; Jaroszewicz, J.; Małkowski, P.; Pawłowska, M.; Piekarska, A.; Simon, K.; Zarębska-Michaluk, D. Recommendations of the Polish Group of Experts for HCV for the Treatment of Hepatitis C in 2023. Clin. Exp. Hepatol. 2023, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebano, A.; Hamed, S.; Bradby, H.; Gil-Salmerón, A.; Durá-Ferrandis, E.; Garcés-Ferrer, J.; Azzedine, F.; Riza, E.; Karnaki, P.; Zota, D.; et al. Migrants’ and Refugees’ Health Status and Healthcare in Europe: A Scoping Literature Review. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essar, M.Y.; Matiashova, L.; Tsagkaris, C.; Vladychuk, V.; Head, M. Infectious Diseases amidst a Humanitarian Crisis in Ukraine: A Rising Concern. Ann. Med. Surg. 2022, 78, 103950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mipatrini, D.; Stefanelli, P.; Severoni, S.; Rezza, G. Vaccinations in Migrants and Refugees: A Challenge for European Health Systems. A Systematic Review of Current Scientific Evidence. Pathog. Glob. Health 2017, 111, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rzymski, P.; Falfushynska, H.; Fal, A. Vaccination of Ukrainian Refugees: Need for Urgent Action. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 75, 1103–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkmann, F.; Friedrichs, A.; Behrens, G.M.N.; Behrens, P.; Berner, R.; Caliebe, A.; Denkinger, C.M.; Giesbrecht, K.; Gussew, A.; Hoffmann, A.T.; et al. Prevalence of Infectious Diseases, Immunity to Vaccine-Preventable Diseases and Chronic Medical Conditions among Ukrainian Refugees in Germany—A Cross Sectional Study from the German Network University Medicine (NUM). J. Infect. Public Health 2024, 17, 642–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasylyev, M.; Skrzat-Klapaczyńska, A.; Bernardino, J.I.; Săndulescu, O.; Gilles, C.; Libois, A.; Curran, A.; Spinner, C.D.; Rowley, D.; Bickel, M.; et al. Unified European Support Framework to Sustain the HIV Cascade of Care for People Living with HIV Including in Displaced Populations of War-Struck Ukraine. Lancet HIV 2022, 9, e438–e448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zelenev, A.; Shea, P.; Mazhnaya, A.; Meteliuk, A.; Pykalo, I.; Marcus, R.; Fomenko, T.; Prokhorova, T.; Altice, F.L. Estimating HIV and HCV Prevalence among People Who Inject Drugs in 5 Ukrainian Cities Using Stratification-Based Respondent Driven and Random Sampling. Int. J. Drug Policy 2019, 67, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzysztoszek, A. Ukraińscy Uchodźcy Wyjeżdżają z Polski do Niemiec: Dlaczego i co to Oznacza? Available online: https://www.euractiv.pl/section/migracje/news/ukrainscy-uchodzcy-wyjezdzaja-z-polski-do-niemiec-dlaczego-i-co-to-oznacza/ (accessed on 14 August 2024).

- Gil-Salmerón, A.; Katsas, K.; Riza, E.; Karnaki, P.; Linos, A. Access to Healthcare for Migrant Patients in Europe: Healthcare Discrimination and Translation Services. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antoniak, S.; Chasela, C.S.; Freiman, M.J.; Stopolianska, Y.; Barnard, T.; Gandhi, M.M.; Liulchuk, M.; Tsenilova, Z.; Viktor, T.; Dible, J.; et al. Treatment Outcomes and Costs of a Simplified Antiretroviral Treatment Strategy for Hepatitis C among Hepatitis C Virus and Human Immuno Deficiency Virus Co-infected Patients in Ukraine. JGH Open 2022, 6, 894–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarębska-Michaluk, D.; Brzdęk, M.; Rzymski, P.; Dobrowolska, K.; Flisiak, R. Hepatitis B Virus Coinfection in Patients Treated for Chronic Hepatitis C: Clinical Characteristics, Risk of Reactivation with Long-Term Follow-up and Effectiveness of Antiviral Therapy. Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 2024, 134, 16638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi-Shearer, D.; Gamkrelidze, I.; Nguyen, M.H.; Chen, D.-S.; Van Damme, P.; Abbas, Z.; Abdulla, M.; Abou Rached, A.; Adda, D.; Aho, I.; et al. Global Prevalence, Treatment, and Prevention of Hepatitis B Virus Infection in 2016: A Modelling Study. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 3, 383–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benade, M.; Rosen, S.; Antoniak, S.; Chasela, C.; Stopolianska, Y.; Barnard, T.; Gandhi, M.M.; Ivanchuk, I.; Tretiakov, V.; Dible, J.; et al. Impact of Direct-Acting Antiviral Treatment of Hepatitis C on the Quality of Life of Adults in Ukraine. BMC Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genowska, A.; Zarębska-Michaluk, D.; Strukcinskiene, B.; Razbadauskas, A.; Moniuszko-Malinowska, A.; Jurgaitis, J.; Flisiak, R. Changing Epidemiological Patterns of Infection and Mortality Due to Hepatitis C Virus in Poland. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://nbp.pl/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Raport_Imigranci_2023_EN.pdf (accessed on 14 August 2024).

- Jančorienė, L.; Rozentāle, B.; Tolmane, I.; Jēruma, A.; Salupere, R.; Buivydienė, A.; Valantinas, J.; Kupčinskas, L.; Šumskienė, J.; Čiupkevičienė, E.; et al. Genotype Distribution and Characteristics of Chronic Hepatitis C Infection in Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Ukraine: The RESPOND-C Study. Medicina 2023, 59, 1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colombo, M.G.; Musabaev, E.I.; Ismailov, U.Y.; Zaytsev, I.A.; Nersesov, A.V.; Anastasiy, I.A.; Karpov, I.A.; Golubovska, O.A.; Kaliaskarova, K.S.; Ac, R.; et al. Consensus on Management of Hepatitis C Virus Infection in Resource-Limited Ukraine and Commonwealth of Independent States Regions. World J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 25, 3897–3919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flisiak, R.; Zarębska-Michaluk, D.; Jaroszewicz, J.; Lorenc, B.; Klapaczyński, J.; Tudrujek-Zdunek, M.; Sitko, M.; Mazur, W.; Janczewska, E.; Pabjan, P.; et al. Changes in Patient Profile, Treatment Effectiveness, and Safety during 4 Years of Access to Interferon-Free Therapy for Hepatitis C Virus Infection. Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 2020, 130, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).