Validation of the Colombian–Spanish Suicidality Scale for Screening Suicide Risk in Clinical and Community Settings

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics and Open Science

2.2. Recruitment and Administration

2.3. Design and Procedure

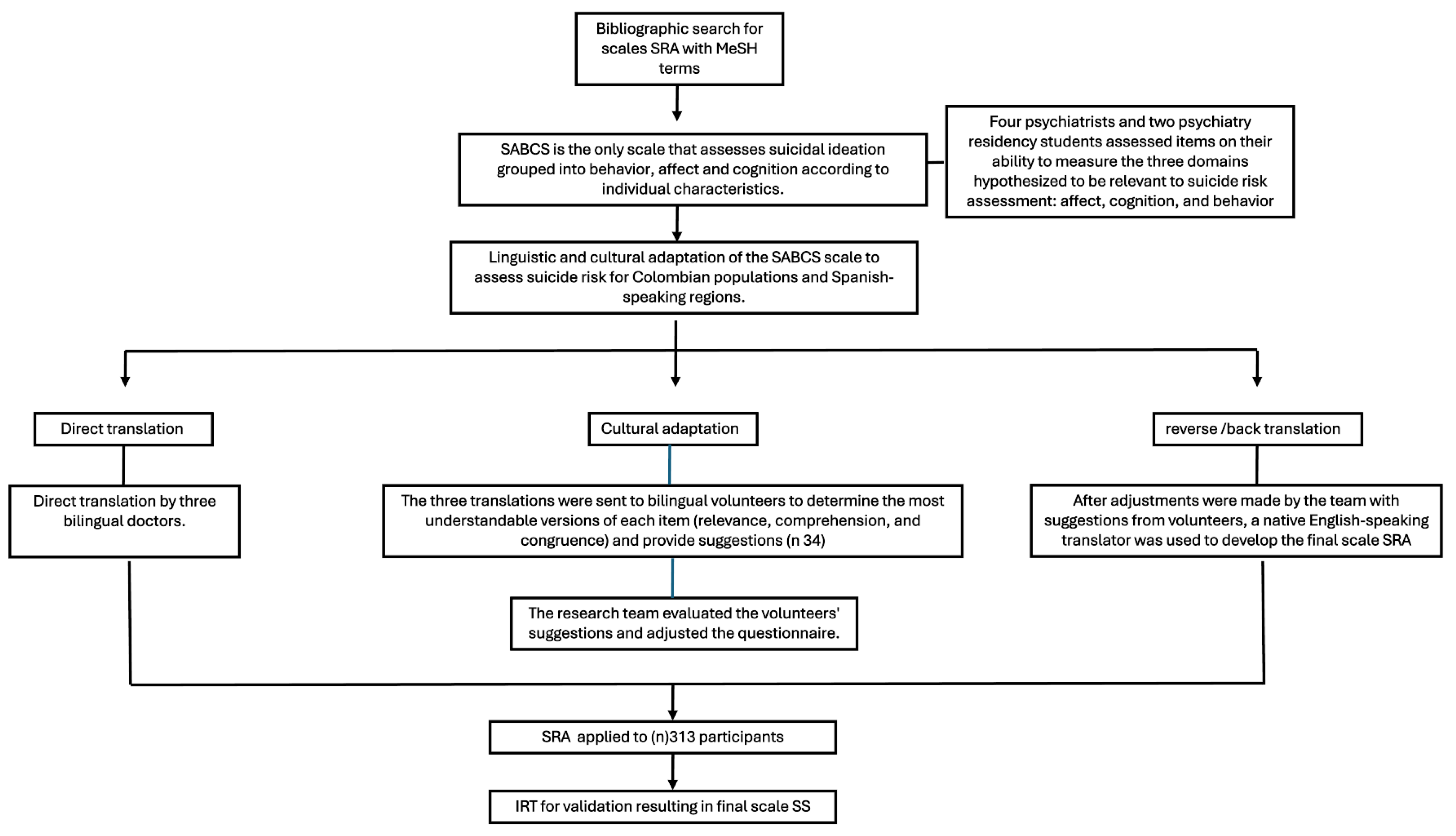

2.4. Translation and Adaptation

2.5. Clinical Ratings

2.6. Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Psychometric Properties and Scale Reliability

3.2. Construct Validity

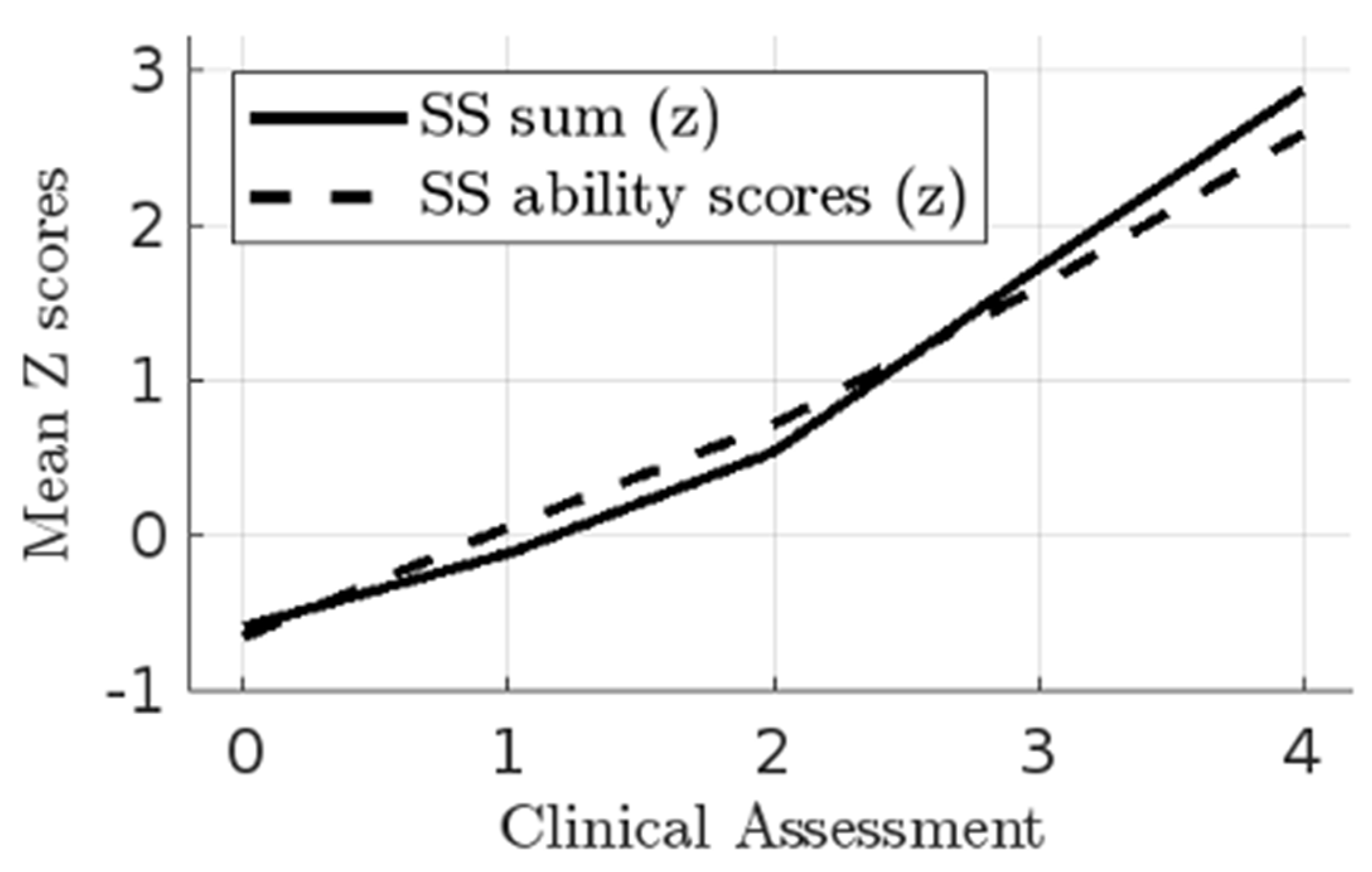

3.3. Clinical and Test Evaluations

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Nunca (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) Muy frecuentemente.

- Nunca (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) Muy Frecuentemente.

- Nunca. (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) Muy Frecuentemente.

- Nunca (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) Muy Frecuentemente.

- No deseo para nada morir (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) Mucho.

- No hay ninguna probabilidad (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) Es muy probable.

- No tengo deseos de suicidarme (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) Tengo un deseo intenso de suicidarme.

- Tengo más razones para VIVIR que para morir (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) Tengo más para MORIR que para vivir.

References

- World Health Organization. Global Health Estimates 2016: Deaths by Cause, Age, Sex, by Country and by Region, 2000–2016. Geneva. 2018. Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/mortality-and-global-health-estimates (accessed on 22 July 2023).

- Naghavi, M. Global, regional, and national burden of suicide mortality 1990 to 2016: Systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. BMJ 2019, 364, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Suicide. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide (accessed on 22 July 2023).

- Chaparro-Narváez, P.; Díaz-Jiménez, D.; Castañeda-Orjuela, C. Tendencia de la mortalidad por suicidio en las áreas urbanas y rurales de Colombia, 1979–2014. Biomédica 2019, 39, 339–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Instituto Nacional de Medicina Legal y Ciencias Forenses. Sistema de Información Clínica y Odontología Forense-SICLICO Forenses-Grupo Centro de Referencia Nacional Sobre Violencia. 2019. Available online: https://www.medicinalegal.gov.co/ (accessed on 22 July 2023).

- Ayala García, J.; La salud en Colombia: Más cobertura, pero menos acceso [Internet]. Bogotá, Colombia: Banco de la República. 2014. Available online: https://www.banrep.gov.co/sites/default/files/publicaciones/archivos/dtser_204.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2023).

- Castro Moreno, L.S.; Fuertes Valencia, L.F.; Pacheco García, O.E.; Muñoz Lozada, C.M. Risk factors associated with suicide attempt as predictors of suicide, Colombia, 2016–2017. Rev. Colomb. Psiquiatr. 2023, 52, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Zapata, C. Factores de Riesgo para la Incidencia de Suicidio en la Región Cafetera de Colombia. 2022. Available online: https://repositorio.ucaldas.edu.co/handle/ucaldas/17604 (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Cañon-Ayala, M.J.; Perdomo-Jurado, Y.E.; Caro-Delgado, A.G. Spatiotemporal analysis of suicide attempts in Colombia from 2018 to 2020. Cad. Saúde Pública 2024, 40, e00119323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenas, Á.; Gómez-Restrepo, C.; Rondón, M. Factores asociados a la conducta suicida en Colombia. Resultados de la Encuesta Nacional de Salud Mental 2015. Rev. Colomb. Psiquiatr. 2016, 45, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations General Assembly. Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (Resolution 70/1). New York. 2015. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 22 July 2023).

- Beck, A.T.; Kovacs, M.; Weissman, A. Assessment of suicidal intention: The Scale for Suicide Ideation. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1979, 47, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T.; Steer, R.A.; Ranieri, W.F. Scale for Suicide Ideation: Psychometric properties of a self-report version. J. Clin. Psychol. 1988, 44, 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, I.W.; Norman, W.H.; Bishop, S.B.; Dow, M.G. The Modified Scale for Suicidal Ideation: Reliability and validity. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1986, 54, 724–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, W.M.; Dohn, H.H.; Bird, J.; Patterson, G.A. Evaluation of suicidal patients: The SAD PERSONS scale. Psychosomatics 1983, 24, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koslowsky, M.; Bleich, A.; Greenspoon, A.; Wagner, B.; Apter, A.; Solomon, Z. Assessing the validity of the Plutchik Suicide Risk Scale. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1991, 25, 155–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangel-Garzón, C.X.; Suárez-Beltrán, M.F.; Escobar-Córdoba, F. Escalas de evaluación de riesgo suicida en atención primaria. Rev. La Fac. Med. Univ. Nac. 2015, 63, 707–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H.; Chaiken, S. The Psychology of Attitudes; Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College: Fort Worth, TX, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, K.M.; Syu, J.-J.; Lello, O.D.; Chew, Y.L.E.; Willcox, C.H.; Ho, R.H.M. The ABC’s of suicide risk assesment: Applying a tripartite approach to individial evaluations. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0127442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, A.T.; Brown, G.; Berchick, R.J.; Stewart, B.L.; Steer, R.A. Relationship between hopelessness and ultimate suicide: A replication with psychiatric outpatients. Am. J. Psychiatry 1990, 147, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T.; Kovacs, M.; Weissman, A. Hopelessness and suicidal behavior. An overview. JAMA 1975, 234, 1146–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, M.; Beck, A.T. Maladaptive cognitive structures in depression. Am. J. Psychiatry 1978, 35, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baca-Garcia, E.; Perez-Rodriguez, M.M.; Oquendo, M.A.; Keyes, K.M.; Hasin, D.S.; Grant, B.F.; Blanco, C. Estimating risk for suicide attempt: Are we asking the right questions? Passive suicidal ideation as a marker for suicidal behavior. J. Affect. Disord. 2011, 134, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, K.; Maltsberger, J.T.; Jobes, D.A.; Leenaars, A.A.; Orbach, I.; Stadler, K.; Dey, P.; Young, R.A.; Valach, L. Discovering the truth in attempted suicide. Am. J. Psychother. 2002, 56, 424–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winters, N.C.; Myers, K.; Proud, L. Ten-year review of rating scales. III: Scales assessing suicidality, cognitive style, and self-esteem. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2002, 41, 1150–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shneidman, E.S. The suicidal mind. In Review of Suicidology; Maris, R.W., Silverman, M.M., Canetto, S.S., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 22–41. [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz, A.G.; Czyz, E.K.; King, C.A. Predicting Future Suicide Attempts Among Adolescent and Emerging Adult Psychiatric Emergency Patients. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2014, 44, 751–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.K.; Beck, A.T.; Steer, R.A.; Grisham, J.R. Risk factors for suicide in psychiatric outpatients: A 20-year prospective study. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2000, 68, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.; Luo, W.; Phung, D.; Harvey, R.; Berk, M.; Kennedy, R.L.; Venkatesh, S. Risk stratification using data from electronic medical records better predicts suicide risks than clinician assessments. BMC Psychiatry 2014, 14, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilén, K.; Ottosson, C.; Castrén, M.; Ponzer, S.; Ursing, C.; Ranta, P.; Ekdahl, K.; Pettersson, H. Deliberate self-harm patients in the emergency department: Factors associated with repeated self-harm among 1524 patients. Emerg. Med. J. EMJ 2011, 28, 1019–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harriss, L.; Hawton, K.; Zahl, D. Value of measuring suicidal intent in the assessment of people attending hospital following self-poisoning or self-injury. Br. J. Psychiatry J. Ment. Sci. 2005, 186, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suokas, J.; Suominen, K.; Isometsä, E.; Ostamo, A.; Lönnqvist, J. Long-term risk factors for suicide mortality after attempted suicide--findings of a 14-year follow-up study. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2001, 104, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, A.; Bagge, C.L.; Gutierrez, P.M.; Konick, L.C.; Kopper, B.A.; Barrios, F.X. The Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised (SBQ-R): Validation with clinical and nonclinical samples. Assessment 2001, 8, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, R.W.; Morris, J.B.; Beck, A.T. Cross-validation of the Suicidal Intent Scale. Psychol. Rep. 1974, 34, 445–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, M.; Beck, A.T.; Weissman, A. The communication of suicidal intent. A reexamination. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1976, 33, 198–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misson, H.; Mathieu, F.; Jollant, F.; Yon, L.; Guillaume, S.; Parmentier, C.; Raust, A.; Jaussent, I.; Slama, F.; Leboyer, M.; et al. Factor analyses of the Suicidal Intent Scale (SIS) and the Risk-Rescue Rating Scale (RRRS): Toward the identification of homogeneous subgroups of suicidal behaviors. J. Affect. Disord. 2010, 121, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubers, A.A.M.; Moaddine, S.; Peersmann, S.H.M.; Stijnen, T.; van Duijn, E.; van der Mast, R.C.; Dekkers, O.M.; Giltay, E.J. Suicidal ideation and subsequent completed suicide in both psychiatric and non-psychiatric populations: A meta-analysis. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2018, 27, 186–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demesmaeker, A.; Chazard, E.; Hoang, A.; Vaiva, G.; Amad, A. Suicide mortality after a nonfatal suicide attempt: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2022, 56, 603–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, K.M.; Wang, L.; Mu, G.M.; Lu, Y.; So, C.; Zhang, W.; Ma, J.; Liu, K.; Wang, W.; Zhang, M.W.-b.; et al. Measuring the suicidal mind: The ‘open source’ Suicidality Scale, for adolescents and adults. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0282009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministerio de Salud. Resolución 8430 de 1993. Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, República de Colombia. 1993; pp. 1–19. Available online: https://www.minsalud.gov.co/sites/rid/Lists/BibliotecaDigital/RIDE/DE/DIJ/RESOLUCION-8430-DE-1993.PDF (accessed on 22 July 2023).

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, L.A.; Watson, D. Constructing validity: Basic issues in objective scale development. Psychol. Assess. 1995, 7, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flora, D.B.; LaBrish, C.; Chalmers, R.P. Old and new ideas for data screening and assumption testing for exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. Front. Psychol. 2012, 3, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Revelle, W.; Zinbarg, R.E. Coefficients alpha, beta, omega, and the glb: Comments on Sijtsma. Psychometrika 2009, 74, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samejima, F. Graded response model. In Encyclopedia of Social Measurement; Kempf-Leonard, K., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004; pp. 77–82. [Google Scholar]

- de Ayala, R.J. The Theory and Practice of Item Response Theory; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Embretson, S.E.; Reise, S.P. Item Response Theory for Psychologists; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; Version 4.1.1; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021; Available online: https://www.R-project.org (accessed on 22 July 2023).

- Rizopoulos, D. ltm: An R Package for Latent Variable Modeling and Item Response Analysis. J. Stat. Softw. 2006, 17, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.W.; Gibbons, L.E.; Crane, P.K. lordif: An R Package for Detecting Differential Item Functioning Using Iterative Hybrid Ordinal Logistic Regression/Item Response Theory and Monte Carlo Simulations. J. Stat. Softw. 2011, 39, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yuan, K.-H. Robust coefficients alpha and omega and confidence intervals with outlying observations and missing data: Methods and software. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2016, 76, 387–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, R.R.; Egberink, I.J.L. Investigating invariant item ordering in personality and clinical scales: Some empirical findings and a discussion. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2012, 72, 589–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meade, A.W.; Lautenschlager, G.J. A Comparison of Item Response Theory and Confirmatory Factor Analytic Methodologies for Establishing Measurement Equivalence/Invariance. Organ. Res. Methods 2004, 7, 361–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullard, M.J. Problems of suicide risk management in the emergency department without fixed, full-time emergency physician. Chang. Yi Xue Za Zhi 1993, 16, 30–38. [Google Scholar]

- Hays, R.D.; Morales, L.S.; Reise, S.P. Item response theory and health outcomes measurement in the 21st century. Med. Care 2000, 38 (Suppl. 9), II28–II42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Item/Scale | Range | M | SD | Skew | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DKS | 1–6 | 1.59 | 1.25 | 2.16 | 6.63 |

| WTD | 1–6 | 1.89 | 1.57 | 1.58 | 4.09 |

| Dead | 1–6 | 2.16 | 1.76 | 1.26 | 3.03 |

| Debate | 1–6 | 2.72 | 1.79 | 1.11 | 2.73 |

| Ideation | 1–6 | 1.95 | 1.61 | 1.55 | 4.05 |

| Predict | 1–6 | 1.63 | 1.26 | 2.14 | 6.69 |

| Meaning | 1–6 | 2.33 | 1.84 | 1.06 | 2.57 |

| RFD | 1–6 | 1.59 | 1.23 | 2.19 | 6.89 |

| SS sum | 8–48 | 15.41 | 10.91 | 1.49 | 1.08 |

| SS person | −0.80–3.08 | 0.10 | 1.04 | 0.94 | −0.17 |

| WTLr | 1–6 | 1.88 | 1.55 | 1.57 | 4.06 |

| Attempt | 1–4 | 1.75 | 1.19 | 1.17 | 2.58 |

| Item | Clus | FA | BA | GRM | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L | h2 | g | h2 | LL | UL | a | ||

| Dead | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.83 | 0.87 | 0.90 | 0.29 | 1.69 | 3.68 |

| Ideation | 0.85 | 0.86 | 0.73 | 0.87 | 0.92 | 0.52 | 1.83 | 3.49 |

| Debate | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.73 | 0.83 | 0.77 | 0.17 | 1.64 | 3.22 |

| Predict | 0.88 | 0.87 | 0.75 | 0.84 | 0.90 | 0.77 | 2.47 | 2.48 |

| DKS | 0.88 | 0.87 | 0.76 | 0.83 | 0.85 | 0.93 | 2.49 | 3.55 |

| Meaning | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.72 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.07 | 1.47 | 3.13 |

| WTD | 0.91 | 0.92 | 0.84 | 0.87 | 0.83 | 0.60 | 2.05 | 3.57 |

| RFD | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.59 | 0.72 | 0.63 | 1.00 | 2.91 | 2.80 |

| Scale | Cluster | FA | BA | ω | 95% CI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fit | RMSR | V | TLI | RMSEA | ωh | ECV | RMSEA | |||

| SS | 0.98 | 0.05 | 0.74 | 0.88 | 0.19 | 0.89 | 0.84 | 0.08 | 0.96 | [0.95, 0.96] |

| Age1 | 0.98 | 0.05 | 0.76 | 0.85 | 0.22 | 0.92 | 0.84 | 0.20 | 0.96 | [0.95, 0.97] |

| Age2 | 0.98 | 0.06 | 0.75 | 0.83 | 0.23 | 0.87 | 0.80 | 0.03 | 0.96 | [0.95, 0.96] |

| Age3 | 0.96 | 0.09 | 0.67 | 0.62 | 0.32 | 0.76 | 0.65 | 0.26 | 0.94 | [0.56, 0.98] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arenas Dávila, A.M.; Pastrana Arias, K.; Castaño Ramírez, Ó.M.; Van den Enden, P.; Castro Navarro, J.C.; González Giraldo, S.; Vera Higuera, D.M.; Harris, K.M. Validation of the Colombian–Spanish Suicidality Scale for Screening Suicide Risk in Clinical and Community Settings. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7782. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13247782

Arenas Dávila AM, Pastrana Arias K, Castaño Ramírez ÓM, Van den Enden P, Castro Navarro JC, González Giraldo S, Vera Higuera DM, Harris KM. Validation of the Colombian–Spanish Suicidality Scale for Screening Suicide Risk in Clinical and Community Settings. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(24):7782. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13247782

Chicago/Turabian StyleArenas Dávila, Ana María, Katherine Pastrana Arias, Óscar Mauricio Castaño Ramírez, Pamela Van den Enden, Juan Carlos Castro Navarro, Santiago González Giraldo, Doris Mileck Vera Higuera, and Keith M. Harris. 2024. "Validation of the Colombian–Spanish Suicidality Scale for Screening Suicide Risk in Clinical and Community Settings" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 24: 7782. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13247782

APA StyleArenas Dávila, A. M., Pastrana Arias, K., Castaño Ramírez, Ó. M., Van den Enden, P., Castro Navarro, J. C., González Giraldo, S., Vera Higuera, D. M., & Harris, K. M. (2024). Validation of the Colombian–Spanish Suicidality Scale for Screening Suicide Risk in Clinical and Community Settings. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(24), 7782. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13247782