Lactate as a Predictor of 30-Day Mortality in Cardiogenic Shock

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

- -

- The internal medicine intensive care unit 13i2;

- -

- The cardiology intensive care unit 13h3.

- -

- SBP < 90 mmHg for >30 min or use of catecholamines to maintain a SBP > 90 mmHg;

- -

- Clinical or radiological signs of pulmonary congestion;

- -

- Reduced end-organ perfusion (neurological impairment, cold extremities, oliguria with <30 mL/h, or serum lactate concentration >2 mmol/L).

2.2. Clinical Data

2.3. Lactate Measurements

- -

- The lactate concentration measured immediately after ICU admission (First Lactate; FL);

- -

- The lactate concentration measured 24 h after ICU admission (Last Lactate; LL);

- -

- The maximum lactate concentration measured in the first 24 h after ICU admission (Peak Lactate; PL);

- -

- Lactate clearance is calculated based on the difference in lactate levels measured at two time points within the first 24 h of ICU admission, indicating the rate at which lactate is removed from the bloodstream in the first 24 h (LC). The formula for LC is as follows:

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Demographics, Admission Details, and Intensive Care Unit Mortality Statistics

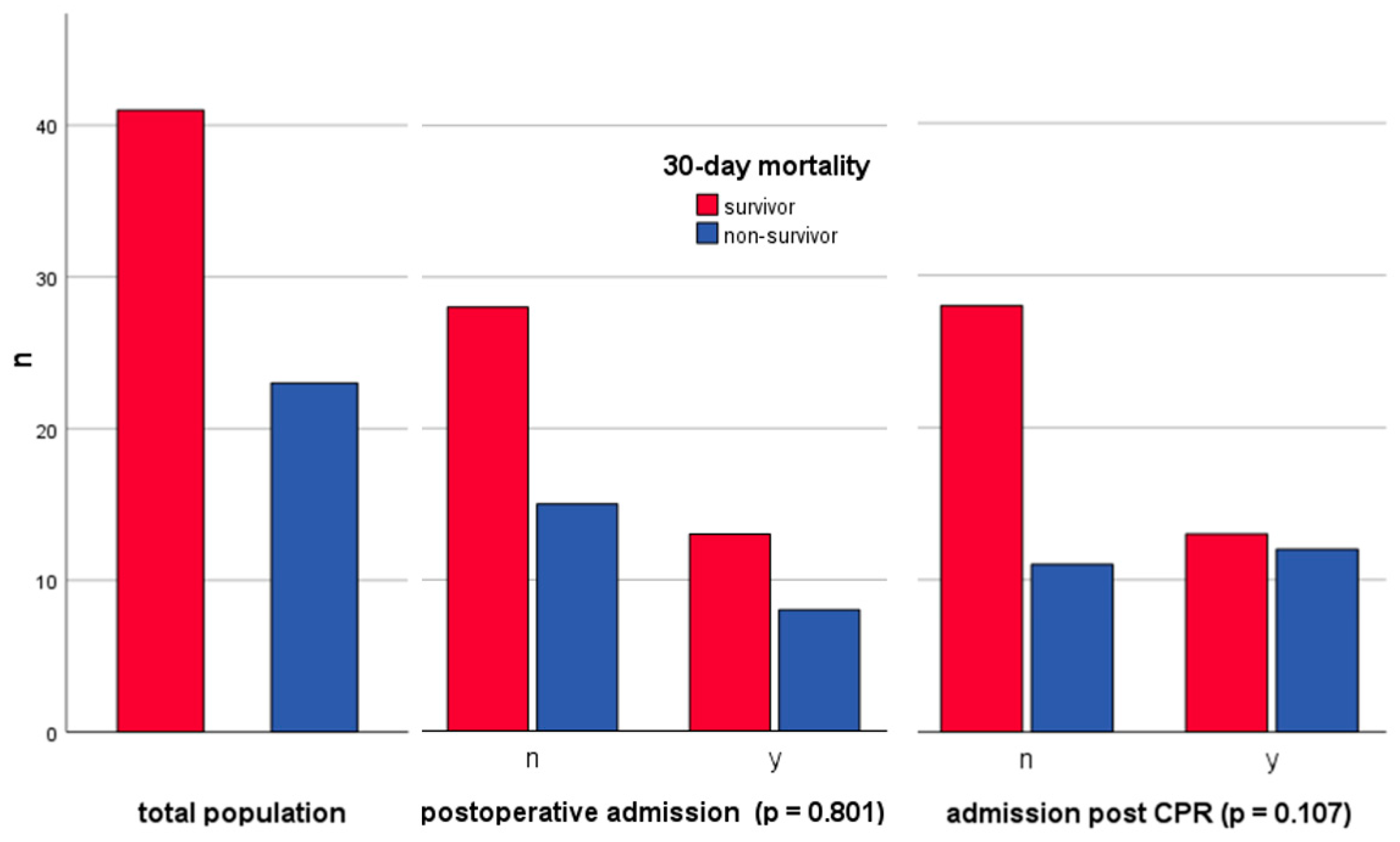

3.2. Postoperative Patient Analysis and Surgical Procedure Overview

3.3. Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation: Admissions, Mortality, Rhythms, and Outcome Correlations

3.4. Logistic Regression Analyses: Baseline Characteristics

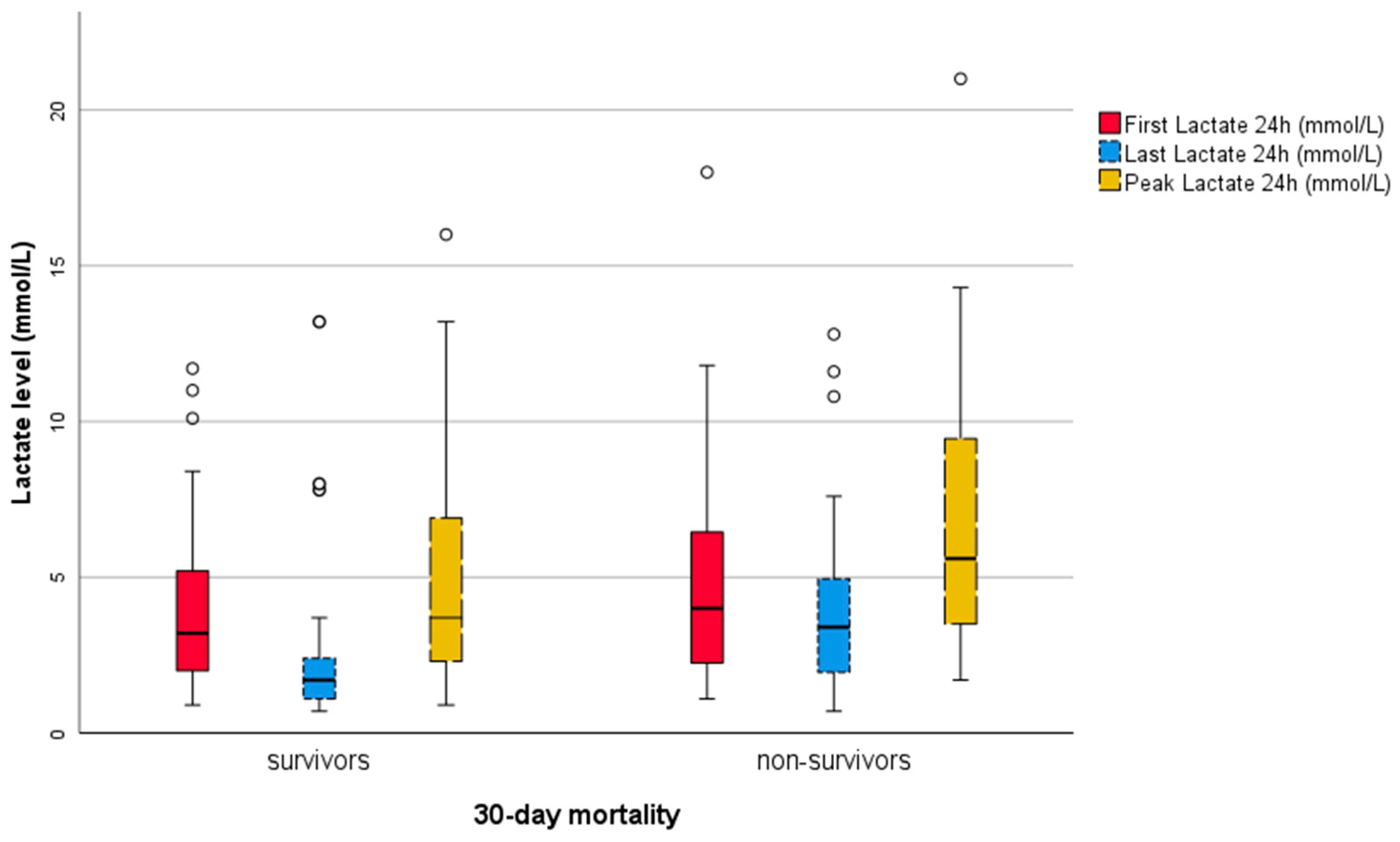

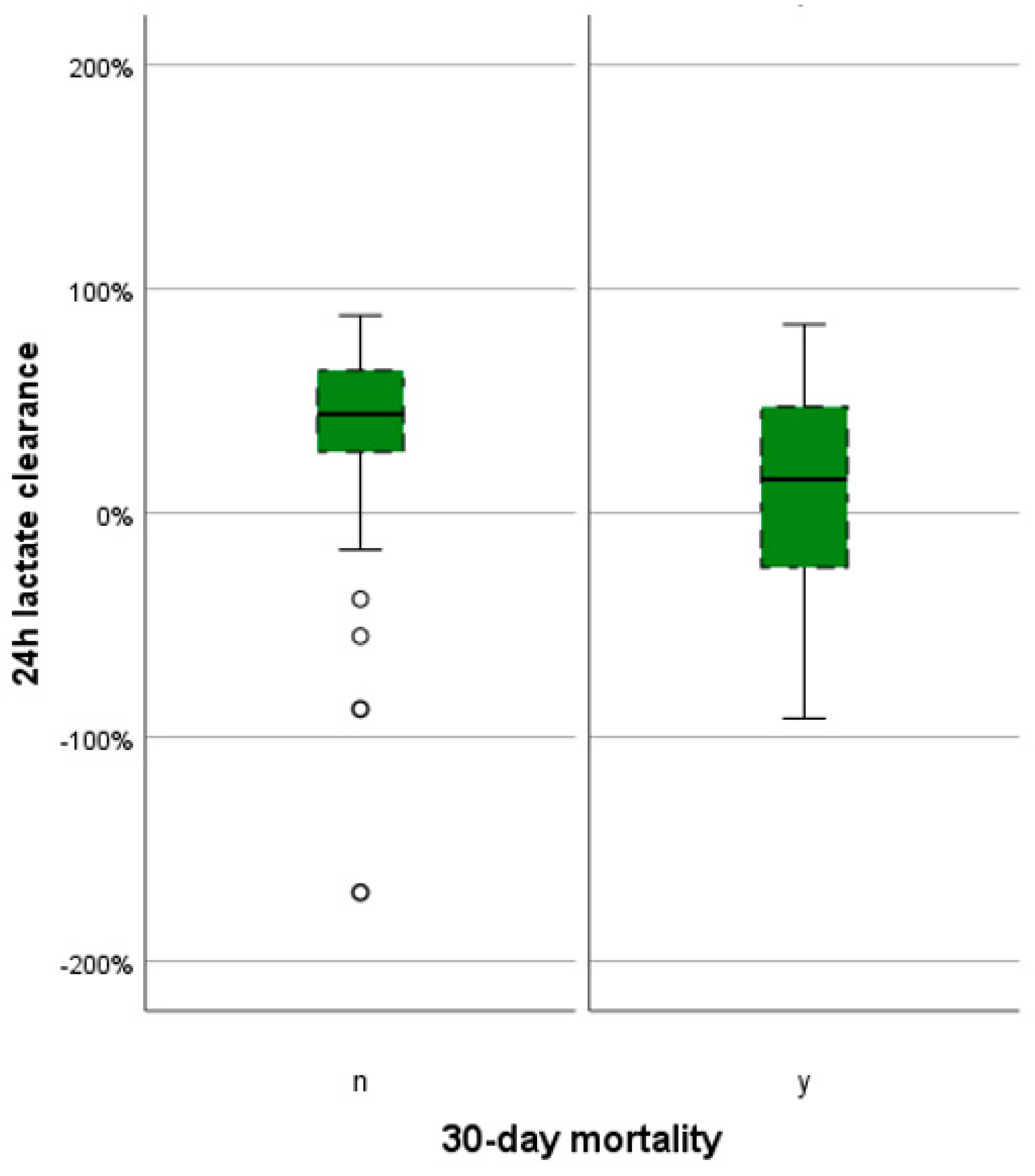

3.5. Graphical and Descriptive Analysis of Lactate Variables

3.6. Scatter Diagrams and Correlations

3.7. Simple Logistic Regression Analyses

3.8. Multivariate Logistic Regression Analyses

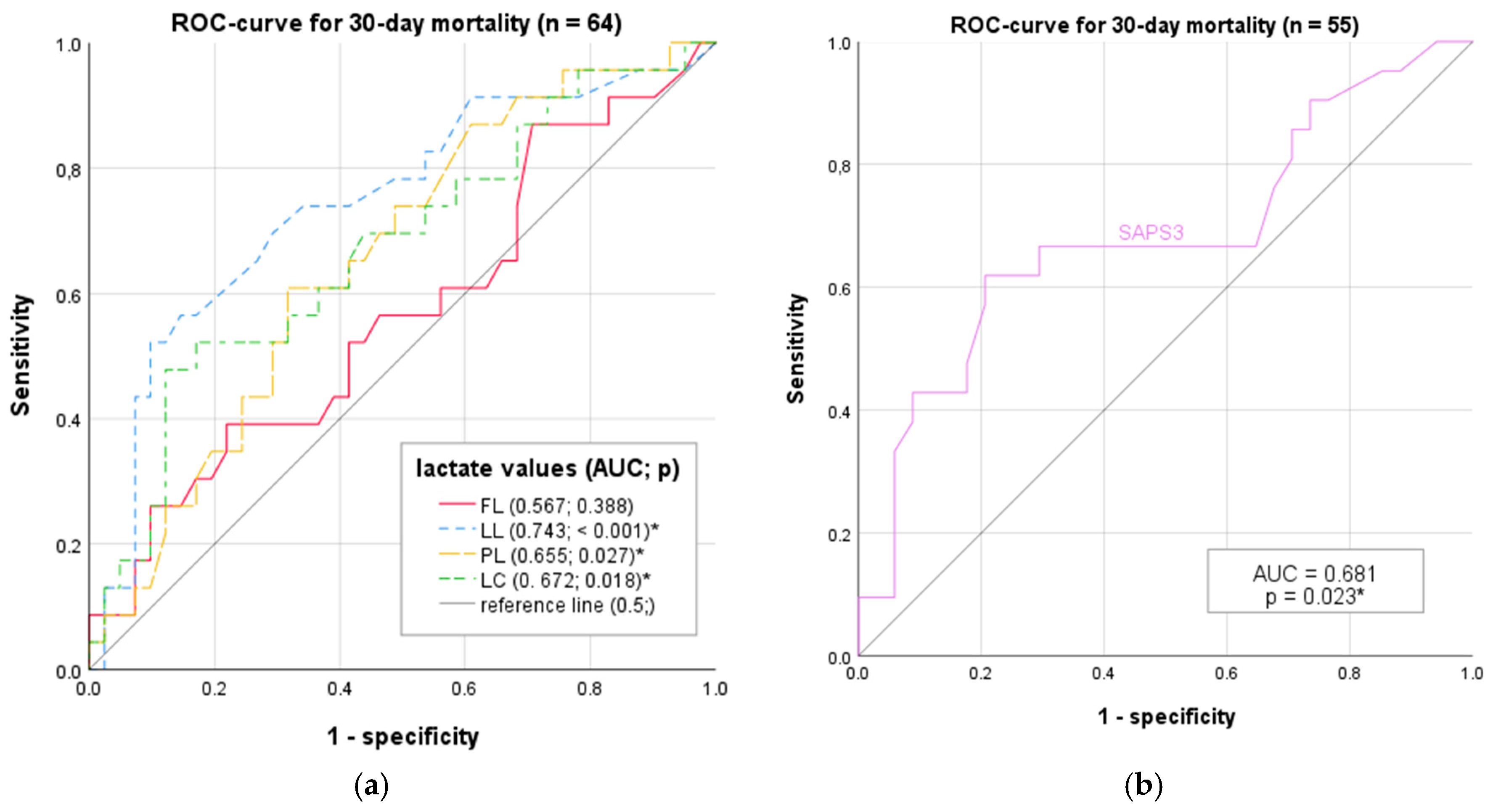

3.9. ROC Analysis

3.10. Diagnostic Characteristics

3.11. DeLong Test for AUC Differences

4. Discussion

Limitations and Strengths

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Van Diepen, S.; Thiele, H. An Overview of International Cardiogenic Shock Guidelines and Application in Clinical Practice. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 2019, 25, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, A.J.; Lam, S.W.; Bauer, S.R.; Guzman, J.A. Lactic Acidosis: Clinical Implications and Management Strategies. Clevel. Clin. J. Med. 2015, 82, 615–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marbach, J.A.; Stone, S.; Schwartz, B.; Pahuja, M.; Thayer, K.L.; Faugno, A.J.; Chweich, H.; Rabinowitz, J.B.; Kapur, N.K. Lactate Clearance Is Associated with Improved Survival in Cardiogenic Shock: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prognostic Factor Studies. J. Card. Fail. 2021, 27, 1082–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindholm, M.G.; Hongisto, M.; Lassus, J.; Spinar, J.; Parissis, J.; Banaszewski, M.; Silva-Cardoso, J.; Carubelli, V.; Salvatore, d.; Sionis, A.; et al. Serum Lactate and A Relative Change in Lactate as Predictors of Mortality in Patients with Cardiogenic Shock—Results from the Cardshock Study. Shock 2020, 53, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doenyas-Barak, K.; Beberashvili, I.; Marcus, R.; Efrati, S. Lactic Acidosis and Severe Septic Shock in Metformin Users: A Cohort Study. Crit. Care 2016, 20, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, I.H.; Yang, J.H.; Jang, W.J.; Chun, W.J.; Oh, J.H.; Park, Y.H.; Ko, Y.-G.; Yu, C.W.; Kim, B.S.; Kim, H.-J.; et al. Clinical Significance of Lactate Clearance in Patients with Cardiogenic Shock: Results from the RESCUE Registry. J. Intensive Care 2021, 9, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno, R.P.; Metnitz, P.G.H.; Almeida, E.; Jordan, B.; Bauer, P.; Campos, R.A.; Iapichino, G.; Edbrooke, D.; Capuzzo, M.; Le Gall, J.-R.; et al. SAPS 3--From Evaluation of the Patient to Evaluation of the Intensive Care Unit. Part 2: Development of a Prognostic Model for Hospital Mortality at ICU Admission. Intensive Care Med. 2005, 31, 1345–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuernau, G.; Desch, S.; de Waha-Thiele, S.; Eitel, I.; Neumann, F.-J.; Hennersdorf, M.; Felix, S.B.; Fach, A.; Böhm, M.; Pöss, J.; et al. Arterial Lactate in Cardiogenic Shock: Prognostic Value of Clearance Versus Single Values. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2020, 13, 2208–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, F.; Philipp, R.K.; Ducas, R.A.; Elliott, J.; Džavík, V.; Jassal, D.S.; Tam, J.W.; Roberts, D.; Garber, P.J.; Ducas, J. The Ability to Achieve Complete Revascularization Is Associated with Improved In-Hospital Survival in Cardiogenic Shock Due to Myocardial Infarction: Manitoba Cardiogenic SHOCK Registry Investigators. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2011, 78, 540–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Gall, J.R.; Lemeshow, S.; Saulnier, F. A New Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS II) Based on a European/North American Multicenter Study. JAMA 1993, 270, 2957–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, P.; Frigyesi, A. Lactate Improves SAPS 3 Prognostication. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2018, 62, 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholz, K.H.; Maier, S.K.G.; Maier, L.S.; Lengenfelder, B.; Jacobshagen, C.; Jung, J.; Fleischmann, C.; Werner, G.S.; Olbrich, H.G.; Ott, R.; et al. Impact of Treatment Delay on Mortality in ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction (STEMI) Patients Presenting with and without Haemodynamic Instability: Results from the German Prospective, Multicentre FITT-STEMI Trial. Eur. Heart J. 2018, 39, 1065–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeymer, U.; Alushi, B.; Lauten, A.; Akin, I.; Desch, S.; De Waha-Thiele, S.; Leistner, D.; Ouarrak, T.; Schneider, S.; Thiele, H. Impact of Pre-Hospital Resuscitation on Short-and Long-Term Mortality in Patients with Cardiogenic Shock and Multivessel Disease. Results of the CULPRIT Trial. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, ehaa946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauridsen, M.D.; Josiassen, J.; Schmidt, M.; Butt, J.H.; Østergaard, L.; Schou, M.; Kjærgaard, J.; Møller, J.E.; Hassager, C.; Torp-Pedersen, C.; et al. Prognosis of Myocardial Infarction-Related Cardiogenic Shock According to Preadmission out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. Resuscitation 2021, 162, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Josiassen, J.; Lerche Helgestad, O.K.; Møller, J.E.; Kjaergaard, J.; Hoejgaard, H.F.; Schmidt, H.; Jensen, L.O.; Holmvang, L.; Ravn, H.B.; Hassager, C. Hemodynamic and Metabolic Recovery in Acute Myocardial Infarction-Related Cardiogenic Shock Is More Rapid among Patients Presenting with out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0244294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rusnak, J.; Schupp, T.; Weidner, K.; Ruka, M.; Egner-Walter, S.; Forner, J.; Bertsch, T.; Kittel, M.; Mashayekhi, K.; Tajti, P.; et al. Differences in Outcome of Patients with Cardiogenic Shock Associated with In-Hospital or Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jentzer, J.C.; van Diepen, S.; Henry, T.D. Understanding How Cardiac Arrest Complicates the Analysis of Clinical Trials of Cardiogenic Shock. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2020, 13, 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, T.; Cecconi, M.; Collinson, P.; Rhodes, A.; Grounds, R.M.; Hamilton, M.A. Raised Serum Cardiac Troponin I Concentrations Predict Hospital Mortality in Intensive Care Unit Patients. Br. J. Anaesth. 2012, 109, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torgersen, C.; Schmittinger, C.A.; Wagner, S.; Ulmer, H.; Takala, J.; Jakob, S.M.; Dünser, M.W. Hemodynamic Variables and Mortality in Cardiogenic Shock: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Crit. Care 2009, 13, R157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, S.; Lazzeri, C.; Vecchio, S.; Giglioli, C.; Margheri, M.; Bernardo, P.; Comeglio, M.; Chiocchini, S.; Gensini, G.F. Predictors of In-Hospital Mortality after Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for Cardiogenic Shock. Int. J. Cardiol. 2007, 114, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreruela, M.; Raurich, J.M.; Ayestarán, I.; Llompart-Pou, J.A. Hyperlactatemia in ICU Patients: Incidence, Causes and Associated Mortality. J. Crit. Care 2017, 42, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollenberg, S.M.; Kavinsky, C.J.; Parrillo, J.E. Cardiogenic Shock. Ann. Intern. Med. 1999, 131, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seymour, C.W.; Gesten, F.; Prescott, H.C.; Friedrich, M.E.; Iwashyna, T.J.; Phillips, G.S.; Lemeshow, S.; Osborn, T.; Terry, K.M.; Levy, M.M. Time to Treatment and Mortality during Mandated Emergency Care for Sepsis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 2235–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Diepen, S.; Katz, J.N.; Albert, N.M.; Henry, T.D.; Jacobs, A.K.; Kapur, N.K.; Kilic, A.; Menon, V.; Ohman, E.M.; Sweitzer, N.K.; et al. Contemporary Management of Cardiogenic Shock: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017, 136, e232–e268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Via, L.; Vasile, F.; Perna, F.; Zawadka, M. Prediction of Fluid Responsiveness in Critical Care: Current Evidence and Future Perspective. Trends Anaesth. Crit. Care 2024, 54, 101316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, M.M.; Evans, L.E.; Rhodes, A. The Surviving Sepsis Campaign Bundle: 2018 Update. Intensive Care Med. 2018, 44, 925–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivers, E.; Nguyen, B.; Havstad, S.; Ressler, J.; Muzzin, A.; Knoblich, B.; Peterson, E.; Tomlanovich, M. Early Goal-Directed Therapy Collaborative Group Early Goal-Directed Therapy in the Treatment of Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 345, 1368–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.E.; Shapiro, N.I.; Trzeciak, S.; Arnold, R.C.; Claremont, H.A.; Kline, J.A. Emergency Medicine Shock Research Network (EMShockNet) Investigators Lactate Clearance vs Central Venous Oxygen Saturation as Goals of Early Sepsis Therapy: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2010, 303, 739–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total (n = 64) | 30-day Mortality | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Survivors (n = 23) | Survivors (n = 41) | |||

| Baseline characteristics | ||||

| Gender (female) | 18 (28%) | 8 (35%) | 10 (24%) | 0.375 1 |

| Age (years) | 64 (55–72) | 66.5 (60–76) | 62 (46–70) | 0.071 2 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.2 (23.9–30.6) | 25.2 (23.9–30.9) | 26.6 (23.9–30.6) | 0.876 2 |

| ICU-stay | ||||

| SAPS3 Score at admission | 70 (57–84) | 82 (61–90) | 67 (53–79) | 0.025 2,* |

| Admission post CPR | 25 (39%) | 12 (52%) | 13 (32%) | 0.107 1 |

| Admission post surgery | 21 (33%) | 8 (35%) | 13 (32%) | 0.801 1 |

| Duration of ICU stay (days) | 9 (4–22) | 10 (3–23) | 9 (6–18) | 0.445 2 |

| Risk factors | ||||

| Immunosuppression | 2 (3%) | 1 (4%) | 1 (2%) | 0.365 1 |

| Hypertension | 29 (48%) | 9 (39%) | 20 (49%) | 0.457 1 |

| Coronary artery disease | 39 (61%) | 18 (78%) | 21 (51%) | 0.033 1,* |

| Peripheral artery disease | 10 (16%) | 4 (17%) | 6 (15%) | 0.771 1 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 13 (20%) | 3 (13%) | 10 (24%) | 0.279 1 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 14 (22%) | 5 (22%) | 9 (22%) | 0.984 1 |

| COPD | 6 (9%) | 3 (13%) | 3 (7%) | 0.451 1 |

| Malignant disease | 3 (5%) | 2 (9%) | 1 (2%) | 0.256 1 |

| Total | 30-Day Mortality | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Survivors | Survivors | ||

| CPR Pre-ICU | n = 25 | n = 12 | n = 13 |

| First Rhythm CPR | |||

| Total shockable | 13 (52%) | 4 (33%) | 9 (69%) |

| Ventricular fibrillation, n (%) | 11 (44%) | 4 (33%) | 7 (54%) |

| Unspecified, shockable, n (%) | 2 (8%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (15%) |

| Total non-shockable, n (%) | 10 (40%) | 6 (50%) | 4 (31%) |

| Asystole, n (%) | 3 (12%) | 1 (8%) | 2 (15%) |

| Pulseless electrical activity, n (%) | 7 (28%) | 5 (42%) | 2 (15%) |

| Unspecified | 2 (8%) | 2 (17%) | 0 (0%) |

| CPR duration [min] | |||

| Maximum CPR duration [min] | 120 | 120 | 120 |

| Minimum CPR duration [min] | 4 | 15 | 4 |

| Median CPR duration [min] | 30 (18–56) | 43 (30–60) | 22 (12–40) |

| 30-day Mortality | Regression Coefficient | p | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (male) | −0.503 | 0.377 | 0.605 | 0.198 | 1.845 |

| Age [Years] | 0.041 | 0.066 | 1.043 | 0.997 | 1.088 |

| BMI [kg/m2] | −0.002 | 0.970 | 1.042 | 0.899 | 1.108 |

| Days ICU stay | −0.006 | 0.731 | 0.994 | 0.963 | 1.027 |

| SAPS 3 Score * | 0.043 | 0.022 * | 1.044 | 1.006 | 1.083 |

| CPR prior to ICU | −0.854 | 0.111 | 0.426 | 0.149 | 1.216 |

| Total comorbidities | 0.096 | 0.588 | 1.101 | 0.777 | 1.560 |

| Descriptive Analysis | Unit | Total | 30-Day Mortality | p-Value * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Survivors | Survivors | ||||

| FL [mmol/L] | Median (quartiles) | 3.5 (2.2–5.7) | 4.0 (2.2–7.0) | 3.2 (2.0–5.2) | 0.378 |

| Maximum | 18.0 | 18.0 | 11.7 | - | |

| Minimum | 0.9 | 1.1 | 0.9 | - | |

| LL [mmol/L] | Median (quartiles) | 2.0 (1.2–3.3) | 3.4 (1.8–5.4) | 1.7 (1.1–2.4) | 0.001 |

| Maximum | 13.2 | 12.8 | 13.2 | - | |

| Minimum | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | - | |

| PL [mmol/L] | Median (quartiles) | 4.3 (2.6–8.6) | 5.6 (3.1–10.1) | 3.7 (2.3–6.9) | 0.040 |

| Maximum | 21.0 | 21.0 | 16.0 | - | |

| Minimum | 0.9 | 1.7 | 0.9 | - | |

| LC [%] | Median (quartiles) | 36.0 (7.3–57.1) | 15.0 (−35.0–48.3) | 44.2 (27.3–63.6) | 0.023 |

| Maximum | 88.1 | 84.1 | 88.1 | - | |

| Minimum | −364.0 | −364.0 | −169.4 | - | |

| SAPS3 | Median (quartiles) | 70 (57−84) | 82 (61–90) | 67 (53–79) | 0.025 |

| Maximum | 125 | 125 | 95 | - | |

| Minimum | 40 | 48 | 40 | - | |

| Correlation | Spearman’s Correlation Coefficients (p-Value) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | FL | LC | PL | SAPS3 | |

| LL | 1 (/) | 0.481 (<0.001) * | −0.535 (<0.001) * | 0.637 (<0.001) * | 0.269 (0.047) * |

| FL | - | 1 (/) | 0.430 (<0.001) * | 0.825 (<0.001) * | 0.243 (0.074) |

| LC | - | - | 1 (/) | 0.063 (0.618) | −0.107 (0.435) |

| PL | - | - | - | 1 (/) | 0.269 (0.047) * |

| SAPS3 | - | - | - | - | 1 (/) |

| Simple Logistic Regression | p-Value | Regression Coefficient | Odds Ratio | Odds Ratio 95%-CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FL | 0.222 | 0.100 | 1.106 | 0.941 | 1.299 |

| LL | 0.020 * | 0.254 | 1.289 | 1.041 | 1.596 |

| PL | 0.067 | 0.122 | 1.129 | 0.992 | 1.286 |

| LC | 0.053 | −0.010 | 0.990 | 0.980 | 1.000 |

| SAPS3 | 0.022 * | 0.043 | 1.044 | 1.006 | 1.083 |

| Multivariant Logistic Regression Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Analysis 1 | variable | LL | p = 0.070 |

| covariable | SAPS3 | p = 0.059 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Klemm, G.; Markart, S.; Hermann, A.; Staudinger, T.; Hengstenberg, C.; Heinz, G.; Zilberszac, R. Lactate as a Predictor of 30-Day Mortality in Cardiogenic Shock. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1932. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13071932

Klemm G, Markart S, Hermann A, Staudinger T, Hengstenberg C, Heinz G, Zilberszac R. Lactate as a Predictor of 30-Day Mortality in Cardiogenic Shock. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(7):1932. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13071932

Chicago/Turabian StyleKlemm, Gregor, Sebastian Markart, Alexander Hermann, Thomas Staudinger, Christian Hengstenberg, Gottfried Heinz, and Robert Zilberszac. 2024. "Lactate as a Predictor of 30-Day Mortality in Cardiogenic Shock" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 7: 1932. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13071932

APA StyleKlemm, G., Markart, S., Hermann, A., Staudinger, T., Hengstenberg, C., Heinz, G., & Zilberszac, R. (2024). Lactate as a Predictor of 30-Day Mortality in Cardiogenic Shock. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(7), 1932. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13071932