Echocardiography in the Ventilated Patient: What the Clinician Has to Know

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Statistical Methodology

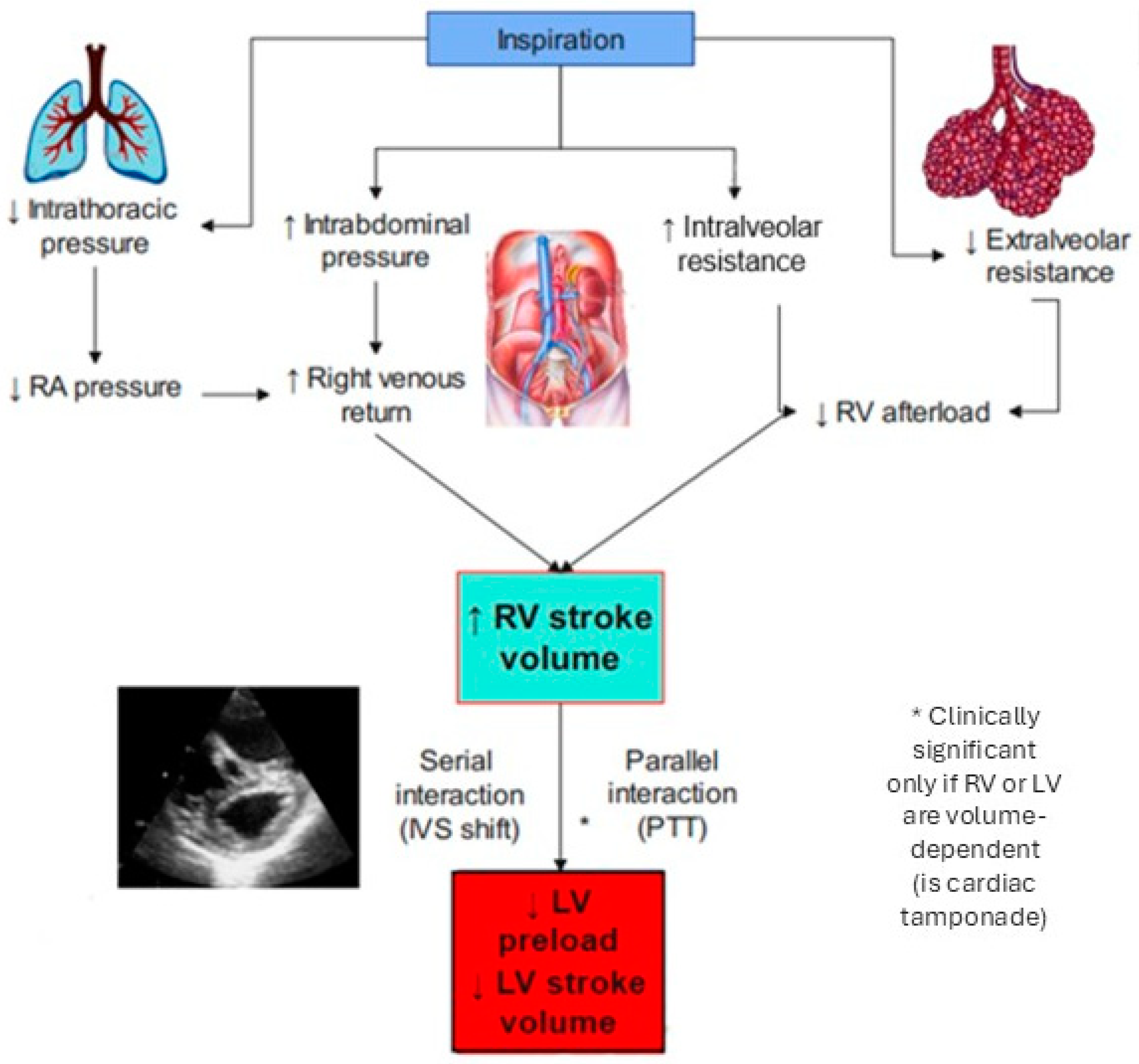

2. Heart–Lung Interaction in Spontaneous Ventilation

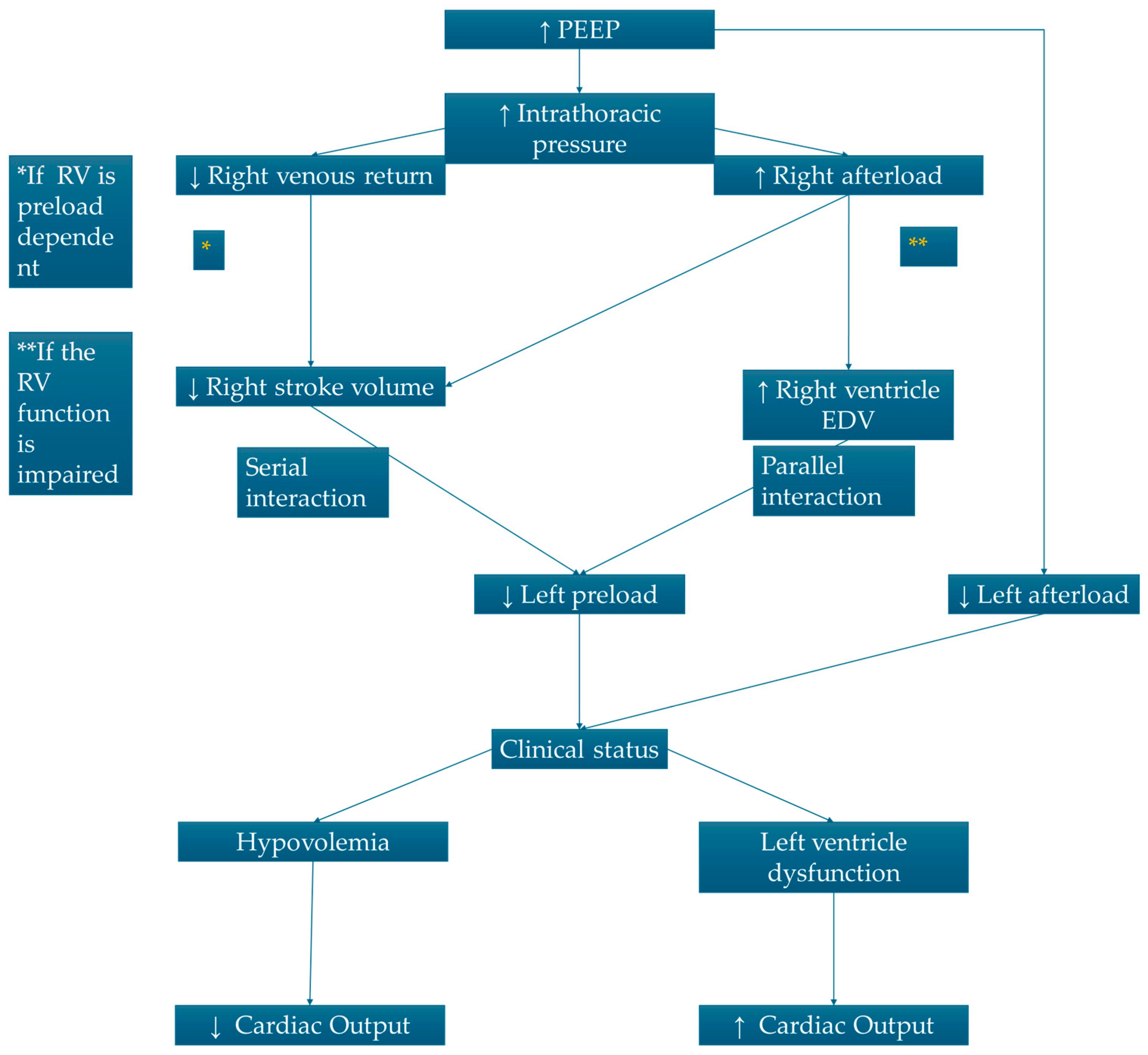

3. Heart–Lung Interaction in Mechanical Ventilation

4. Echocardiographic Evaluation in Mechanical Ventilation

- -

- Normal RV function;

- -

- Right ventricular failure (RVF) without right ventricular systolic dysfunction (RVSD);

- -

- RVSD without RVF;

- -

- Combined RVF and RVSD.

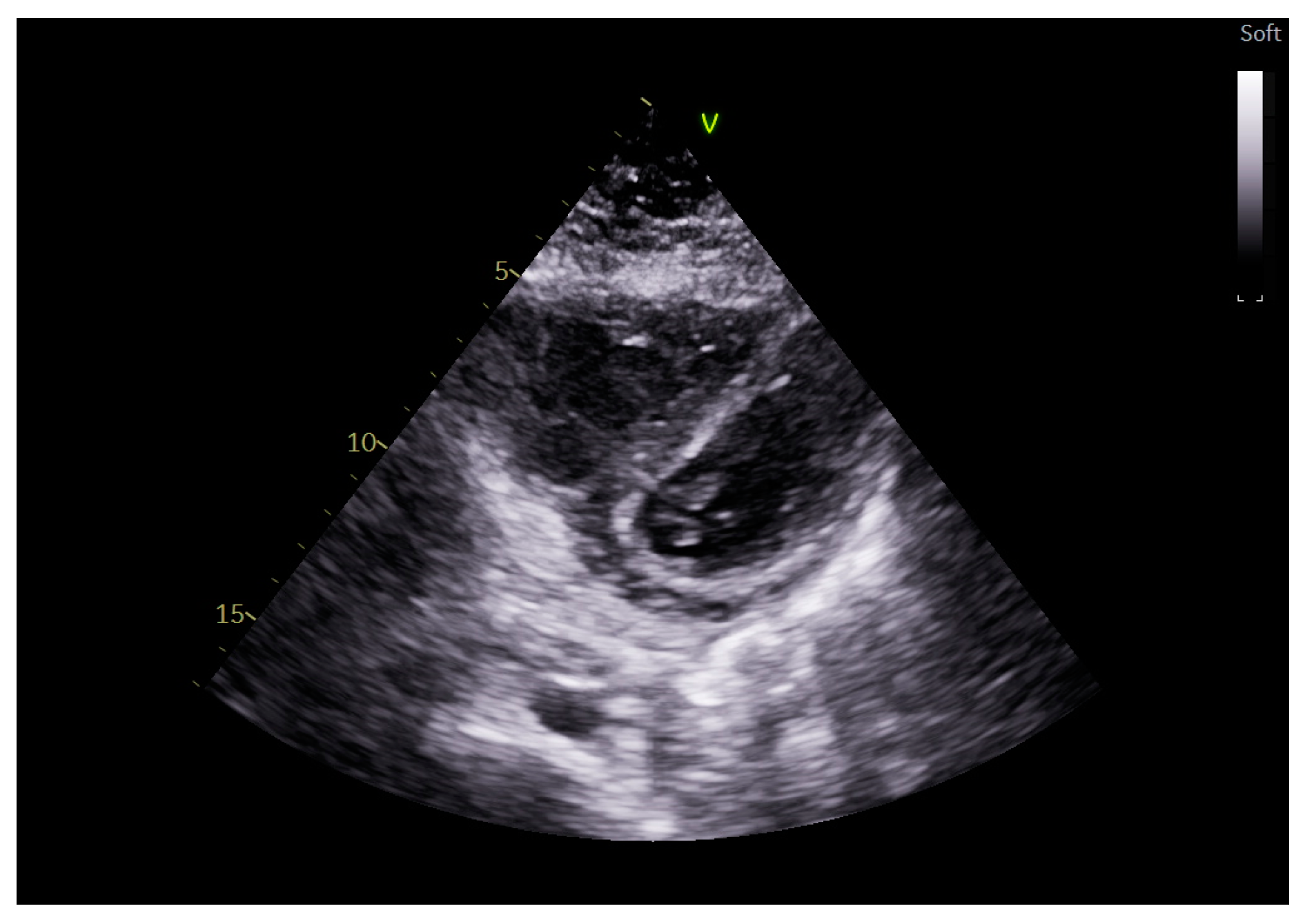

5. Right Ventricular Echocardiographic Evaluation

6. Echocardiography and Volume Management

- -

- IVC diameter in ventilated patient predicts fluid responsiveness with a specificity of 95% when the end-expiratory diameter is <8 mm [41], while a reduction in IVC diameter during inspiration of 18% could predict fluid responsiveness in septic, ventilated patients with 90% of sensibility and specificity [42]. Commonly, in patients with right heart failure and severe tricuspid regurgitation, it is common to observe IVC dilatation regardless of volume status.

- -

- Left ventricular end diastolic area (LVEDA), as measured with transesophageal echocardiography in ICU at an angle of 0° or 90° (respectively four chamber view and two chamber view), is not sufficient alone to predict fluid responsiveness. It is worth mentioning that one observational study found that the combination of LVEDA (<21 cm2) and the ratio of PW Doppler of left ventricular early filling (E peak wave) and the tissue Doppler of the mitral anulus (e’avg) as E/e’avg (<7) could predict fluid responsiveness in patients undergoing coronary surgeries without heart failure with reduced left ventricular function (HFrEF) and with an AUC of 0.9 [43]. Static parameters are less useful in patients with severe left ventricular dysfunction as they are unable to evaluate the response of the cardiovascular system to the fluid administration. Therefore, the data derived from these parameters must be considered only as part of the clinical–instrumental evaluation of the patient, and necessarily integrated with the dynamic parameters, especially in ventilated and critically ill patients with ventricular dysfunction.

- (1)

- Fluid challenge (FC): The fluid challenge is based on the administration of a 500 mL bolus of crystalloids in 10–15 min and subsequent observation of SV change. A change greater than 15% defines fluid responsiveness [45]. When monitoring SV with pulse-contour analysis, a minifluid challenge can be useful in place of echocardiography. By administering 100 cc of crystalloids in one minute, the 6% change in SV (which turns out to be too small to be detected by the echocardiographic method of VTI on LVOT) predicts fluid responsiveness to a global bolus of 250 cc of crystalloids [46]. In a small observational study of 30 patients admitted to cardio-thoracic intensive care, it was observed that in patients responsive to a fluid challenge (FC), but not in nonresponders, administration of a bolus of crystalloids during FC improved ventriculo-arterial coupling, reducing arterial elastance and consequently systemic arterial resistances [47].

- (2)

- Passive leg raise (PLR): PLR works analogous to the FC; however, instead of administering a bolus of fluid from the outside, elevation of the legs and supination of the trunk results in a shift of approximately 300–500 cc of blood from the splanchnic venous compartment and lower extremities to the right ventricle; thus, similar to the FC, the cutoff for defining fluid responsiveness is a SV change of 15% (calculated as the change in LVOT-VTI). It is essential to remember that for proper performance of the test, the patient must initially be positioned in a semisupine position, with the trunk tilted about 45°, and then, concurrently with leg raising, the trunk is moved to a supine position. In addition, it is necessary to exclude the influence of adrenergic stimulation determined by pain [48].

- (3)

- Occlusion tests: In ventilated patients, as described above, inspiration augments PEEP, which reduces venous return to the right ventricle. Thus, if the left ventricle is preload dependent, through serial and parallel interaction, then the left ventricle SV is reduced while the opposite happens during end-expiration. This concept is the basis for the end-expiration occlusion (EEO) test and end-inspiration occlusion (EIO) test. Ventilation interruption during end-expiration for 15 s (EEO) followed by ventilation interruption during end-inspiration for 15 s (EIO) can enhance the observation of LVSV variation in echocardiography. The combination of EEO and EIO was tested in 30 ventilated patients and the absolute variation in SV of 13% was able to predict fluid responsiveness with a sensitivity and specificity of 93% (AUC 0.973) [49]. In general, dynamic parameters are useful to predict fluid responsiveness in ventilated patients with tidal volume (TV > 8 mL/kg), while in particular, the EEO test, PLR, and FC are useful to assess even patients with lung protective ventilation (TV < 8 mL/kg) [50].

7. Diaphragm Anatomy and Physiology

8. Diaphragmatic Dysfunction in Mechanically Ventilated Patients in the Intensive Care Unit

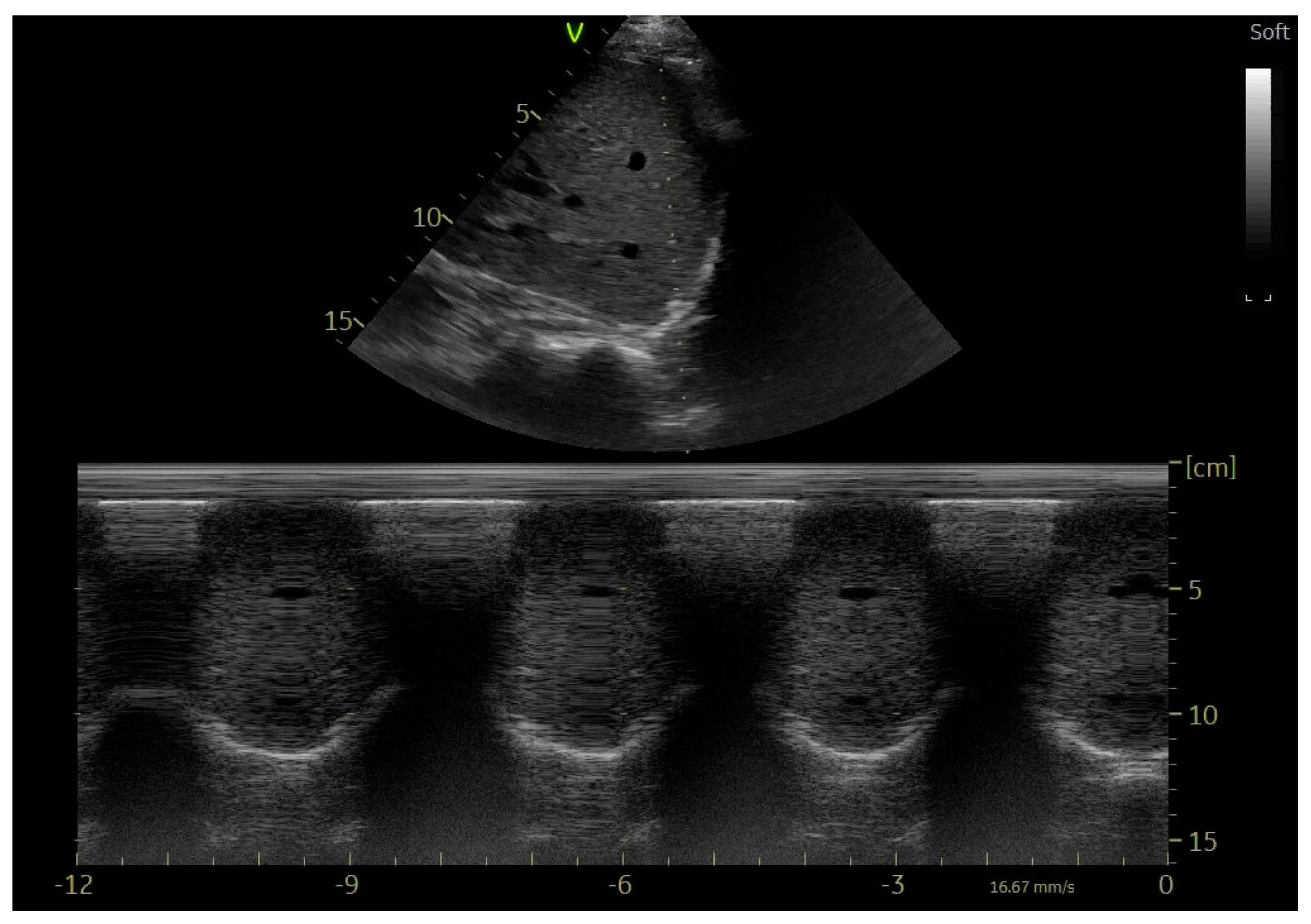

9. Echocardiographic Assessment of Diaphragmatic Function

10. Evaluation of the Diaphragm in Ventilated Patient

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grbler, M.R.; Wigger, O.; Berger, D.; Blchlinger, S. Basic concepts of heart-lung interactions during mechanical ventilation. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2017, 147, w14491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, e1–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marini, M.; Caretta, G.; Vagnarelli, F.; Lucà, F.; Biscottini, E.; Lavorgna, A.; Procaccini, V.; Riva, L.; Vianello, G.; Aspromonte, N.; et al. Gli effetti emodinamici della pressione positiva di fine espirazione. G. Ital. Cardiol. 2017, 18, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekerdemian, L.; Bohn, D. Cardiovascular effects of mechanical ventilation. Arch. Dis. Child. 1999, 80, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wise, R.A.; Robotham, J.L.; Summer, W.R. Effects of spontaneous ventilation on the circulation. Lung 1981, 159, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abel, J.G.; Salerno, T.A.; Panos, A.; Greyson, N.; Rice, T.W.; Teoh, K.; Lichtenstein, S.V. Cardiovascular Effects of Positive Pressure Ventilation in Humans. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1987, 43, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luecke, T.; Pelosi, P. Clinical review: Positive end-expiratory pressure and cardiac output. Crit. Care 2005, 9, 607–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunham-Snary, K.J.; Wu, D.; Sykes, E.A.; Thakrar, A.; Parlow, L.R.; Mewburn, J.D.; Parlow, J.L.; Archer, S.L. Hypoxic Pulmonary Vasoconstriction. Chest 2017, 151, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, S.S.; Pinsky, M.R. Heart-lung interactions during mechanical ventilation: The basics. Ann. Transl. Med. 2018, 6, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jossart, A.; Gerber, B.; Houard, L.; Pilet, B.; O’connor, S.; Gilles, R. Distribution of normalized pulmonary transit time per pathology in a population of routine CMR examinations. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2023, 40, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieillard-Baron, A.; Matthay, M.; Teboul, J.L.; Bein, T.; Schultz, M.; Magder, S.; Marini, J.J. Experts’ opinion on management of hemodynamics in ARDS patients: Focus on the effects of mechanical ventilation. Intensiv. Care Med. 2016, 42, 739–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharf, S.M.; Pinsky, M.R.; Magder, S. Respiratory-Circulatory Interactions in Health and Disease; Dekker, M., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko, Y.; Floras, J.S.; Usui, K.; Plante, J.; Tkacova, R.; Kubo, T.; Ando, S.-I.; Bradley, T.D. Cardiovascular Effects of Continuous Positive Airway Pressure in Patients with Heart Failure and Obstructive Sleep Apnea. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 1233–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Huang, W.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Liu, D. Critical Care Ultrasound Study Group Prevalence and prognostic value of various types of right ventricular dysfunction in mechanically ventilated septic patients. Ann. Intensiv. Care 2021, 11, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, B.T.; Bradley, L.A.; Dempsey, T.M.; Puro, A.C.; Adams, J.Y. Management of Mechanical Ventilation in Decompensated Heart Failure. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2016, 3, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhivathanan, P.; Corredor, C.; Smith, A. Perioperative implications of pericardial effusions and cardiac tamponade. BJA Educ. 2020, 20, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudski, L.G.; Lai, W.W.; Afilalo, J.; Hua, L.; Handschumacher, M.D.; Chandrasekaran, K.; Solomon, S.D.; Louie, E.K.; Schiller, N.B. Guidelines for the Echocardiographic Assessment of the Right Heart in Adults: A Report from the American Society of Echocardiography. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2010, 23, 685–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, R.M.; Badano, L.P.; Mor-Avi, V.; Afilalo, J.; Armstrong, A.; Ernande, L.; Flachskampf, F.A.; Foster, E.; Goldstein, S.A.; Kuznetsova, T.; et al. Recommendations for Cardiac Chamber Quantification by Echocardiography in Adults: An Update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2015, 16, 233–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieillard-Baron, A.; Prin, S.; Chergui, K.; Dubourg, O.; Jardin, F. Echo–Doppler Demonstration of Acute Cor Pulmonale at the Bedside in the Medical Intensive Care Unit. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2002, 166, 1310–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clancy, D.J.; Mclean, A.; Slama, M.; Orde, S.R. Paradoxical septal motion: A diagnostic approach and clinical relevance. Australas. J. Ultrasound Med. 2018, 21, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evrard, B.; Woillard, J.-B.; Legras, A.; Bouaoud, M.; Gourraud, M.; Humeau, A.; Goudelin, M.; Vignon, P. Diagnostic, prognostic and clinical value of left ventricular radial strain to identify paradoxical septal motion in ventilated patients with the acute respiratory distress syndrome: An observational prospective multicenter study. Crit. Care 2023, 27, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smolarek, D.; Gruchała, M.; Sobiczewski, W. Echocardiographic evaluation of right ventricular systolic function: The traditional and innovative approach. Cardiol. J. 2017, 24, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, V.C.-C.; Takeuchi, M. Echocardiographic assessment of right ventricular systolic function. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 2018, 8, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cameli, M.; Mondillo, S.; Galderisi, M.; Mandoli, G.E.; Ballo, P.; Nistri, S.; Capo, V.; D’Ascenzi, F.; D’Andrea, A.; Esposito, R.; et al. L’ecocardiografia speckle tracking: Roadmap per la misurazione e l’utilizzo clinico. G Ital Cardiol. 2017, 18, 253–269. [Google Scholar]

- Tadic, M.; Nita, N.; Schneider, L.; Kersten, J.; Buckert, D.; Gonska, B.; Scharnbeck, D.; Reichart, C.; Belyavskiy, E.; Cuspidi, C.; et al. The Predictive Value of Right Ventricular Longitudinal Strain in Pulmonary Hypertension, Heart Failure, and Valvular Diseases. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 698158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vos, M.E.; Cox, E.G.M.; Schagen, M.R.; Hiemstra, B.; Wong, A.; Koeze, J.; van der Horst, I.C.C.; Wiersema, R.; SICS Study Group. Right ventricular strain measurements in critically ill patients: An observational SICS sub-study. Ann. Intensiv. Care 2022, 12, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Bashir, Z.; Chen, E.W.; Kadiyala, V.; Sherrod, C.F.; Has, P.; Song, C.; Ventetuolo, C.E.; Simmons, J.; Haines, P. Invasive Mechanical Ventilation Is Associated with Worse Right Ventricular Strain in Acute Respiratory Failure Patients. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2024, 11, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McErlane, J.; McCall, P.; Willder, J.; Berry, C.; Ben Shelley, B. Right ventricular free wall longitudinal strain is independently associated with mortality in mechanically ventilated patients with COVID-19. Ann. Intensiv. Care 2022, 12, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, S.; Walker, S.; Loudon, B.L.; Gollop, N.D.; Wilson, A.M.; Lowery, C.; Frenneaux, M.P. Assessment of pulmonary artery pressure by echocardiography—A comprehensive review. IJC Heart Vasc. 2016, 12, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humbert, M.; Kovacs, G.; Hoeper, M.M.; Badagliacca, R.; Berger, R.M.F.; Brida, M.; Carlsen, J.; Coats, A.J.S.; Escribano-Subias, P.; Ferrari, P.; et al. 2022 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension. Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 3618–3731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franchi, F.; Faltoni, A.; Cameli, M.; Muzzi, L.; Lisi, M.; Cubattoli, L.; Cecchini, S.; Mondillo, S.; Biagioli, B.; Taccone, F.S.; et al. Influence of Positive End-Expiratory Pressure on Myocardial Strain Assessed by Speckle Tracking Echocardiography in Mechanically Ventilated Patients. BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 918548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badano, L.P.; Kolias, T.J.; Muraru, D.; Abraham, T.P.; Aurigemma, G.; Edvardsen, T.; D’Hooge, J.; Donal, E.; Fraser, A.G.; Marwick, T.; et al. Standardization of left atrial, right ventricular, and right atrial deformation imaging using two-dimensional speckle tracking echocardiography: A consensus document of the EACVI/ASE/Industry Task Force to standardize deformation imaging. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2018, 19, 591–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alviar, C.L.; Miller, P.E.; McAreavey, D.; Katz, J.N.; Lee, B.; Moriyama, B.; Soble, J.; van Diepen, S.; Solomon, M.A.; Morrow, D.A. Positive Pressure Ventilation in the Cardiac Intensive Care Unit. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 72, 1532–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagueh, S.F.; Smiseth, O.A.; Appleton, C.P.; Byrd, B.F., 3rd; Dokainish, H.; Edvardsen, T.; Flachskampf, F.A.; Gillebert, T.C.; Klein, A.L.; Lancellotti, P.; et al. Recommendations for the Evaluation of Left Ventricular Diastolic Function by Echocardiography: An Update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2016, 29, 277–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smiseth, O.A.; Morris, D.A.; Cardim, N.; Cikes, M.; Delgado, V.; Donal, E.; Flachskampf, F.A.; Galderisi, M.; Gerber, B.L.; Gimelli, A.; et al. Multimodality imaging in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction: An expert consensus document of the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur. Heart J.-Cardiovasc. Imaging 2021, 23, e34–e61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, X.; Xu, H.; Liu, Z.; Wu, J.; Cao, D.; Chen, J.; Chen, M.; Liu, Y.; Guan, X. Does Respiratory Variation in Inferior Vena Cava Diameter Predict Fluid Responsiveness in Mechanically Ventilated Patients? A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Anesthesia Analg. 2018, 127, 1157–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chayapinun, V.; Koratala, A.; Assavapokee, T. Seeing beneath the surface: Harnessing point-of-care ultrasound for internal jugular vein evaluation. World J. Cardiol. 2024, 16, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarracino, F.; Ferro, B.; Forfori, F.; Bertini, P.; Magliacano, L.; Pinsky, M.R. Jugular vein distensibility predicts fluid responsiveness in septic patients. Crit. Care 2014, 18, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, K.L.; Snyder, P.S. Fluid therapy in the cardiac patient. Veter. Clin. N. Am. Small Anim. Pract. 1998, 28, 663–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guarracino, F.; Bertini, P.; Pinsky, M.R. Management of cardiovascular insufficiency in ICU: The BEAT approach. Minerva Anestesiol. 2021, 87, 476–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musu, M.; Guddelmoni, L.; Murgia, F.; Mura, S.; Bonu, F.; Mura, P.; Finco, G. Prediction of fluid responsiveness in ventilated critically ill patients. J. Emerg. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 8, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbier, C.; Loubières, Y.; Schmit, C.; Hayon, J.; Ricôme, J.-L.; Jardin, F.; Vieillard-Baron, A. Respiratory changes in inferior vena cava diameter are helpful in predicting fluid responsiveness in ventilated septic patients. Intensiv. Care Med. 2004, 30, 1740–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-B.; Soh, S.; Song, J.-W.; Kim, M.-Y.; Kwak, Y.-L.; Shim, J.-K. Combination of Static Echocardiographic Indices for the Prediction of Fluid Responsiveness in Patients Undergoing Coronary Surgery: A Pilot Study. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, P. Rationale for using the velocity–time integral and the minute distance for assessing the stroke volume and cardiac output in point-of-care settings. Ultrasound J. 2020, 12, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messina, A.; Calabrò, L.; Pugliese, L.; Lulja, A.; Sopuch, A.; Rosalba, D.; Morenghi, E.; Hernandez, G.; Monnet, X.; Cecconi, M. Fluid challenge in critically ill patients receiving haemodynamic monitoring: A systematic review and comparison of two decades. Crit. Care 2022, 26, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biais, M.; de Courson, H.; Lanchon, R.; Pereira, B.; Bardonneau, G.; Griton, M.; Sesay, M.; Nouette-Gaulain, K. Mini-fluid Challenge of 100 mL of Crystalloid Predicts Fluid Responsiveness in the Operating Room. Anesthesiology 2017, 127, 450–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huette, P.; Abou-Arab, O.; Longrois, D.; Guinot, P.-G. Fluid expansion improve ventriculo-arterial coupling in preload-dependent patients: A prospective observational study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2020, 20, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monnet, X.; Teboul, J.-L. Passive leg raising: Five rules, not a drop of fluid! Crit. Care 2015, 19, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jozwiak, M.; Depret, F.; Teboul, J.-L.; Alphonsine, J.-E.; Lai, C.; Richard, C.; Monnet, X. Predicting Fluid Responsiveness in Critically Ill Patients by Using Combined End-Expiratory and End-Inspiratory Occlusions With Echocardiography. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 45, e1131–e1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, J.I.A.; Ruiz, J.D.C.; Fernández, J.J.D.; Zuñiga, W.F.A.; Ospina-Tascón, G.A.; Martínez, L.E.C. Predictors of fluid responsiveness in critically ill patients mechanically ventilated at low tidal volumes: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Intensiv. Care 2021, 11, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, J.-E.S. Assessing Fluid Intolerance with Doppler Ultrasonography: A Physiological Framework. Med. Sci. 2022, 10, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, R.H.; dos Santos, M.H.C.; Ramos, F.J.D.S. Beyond fluid responsiveness: The concept of fluid tolerance and its potential implication in hemodynamic management. Crit. Care Sci. 2023, 35, 226–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar, S.; Yee, C.; Lichtenstein, D.; Sellier, M.; Leviel, F.; Arab, O.A.; Marc, J.; Miclo, M.; Dupont, H.; Lorne, E. Assessment of fluid unresponsiveness guided by lung ultrasound in abdominal surgery: A prospective cohort study. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, S.; Sauthoff, H. Assessing Extravascular Lung Water With Ultrasound: A Tool to Individualize Fluid Management? J. Intensiv. Care Med. 2020, 35, 1356–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, J.S.M.; Prager, R.; Rola, P.; Haycock, K.; Basmaji, J.; Hernández, G. Unifying Fluid Responsiveness and Tolerance With Physiology: A Dynamic Interpretation of the Diamond–Forrester Classification. Crit. Care Explor. 2023, 5, e1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downey, R. Anatomy of the Normal Diaphragm. Thorac. Surg. Clin. 2011, 21, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Troyer, A.; Wilson, T.A. Action of the diaphragm on the rib cage. J. Appl. Physiol. 2016, 121, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vetrugno, L.; Guadagnin, G.M.; Barbariol, F.; Langiano, N.; Zangrillo, A.; Bove, T. Ultrasound Imaging for Diaphragm Dysfunction: A Narrative Literature Review. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesthesia 2019, 33, 2525–2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A.J.; Katz, M.G.; Katz, R.; Mayerfeld, D.; Hauptman, E.; Schachner, A. Phrenic Nerve Injury After Coronary Artery Grafting: Is It Always Benign? Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1997, 64, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, S.; Nguyen, T.; Taylor, N.; Friscia, M.E.; Budak, M.T.; Rothenberg, P.; Zhu, J.; Sachdeva, R.; Sonnad, S.; Kaiser, L.R.; et al. Rapid Disuse Atrophy of Diaphragm Fibers in Mechanically Ventilated Humans. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 358, 1327–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goligher, E.C.; Brochard, L.J.; Reid, W.D.; Fan, E.; Saarela, O.; Slutsky, A.S.; Kavanagh, B.P.; Rubenfeld, G.D.; Ferguson, N.D. Diaphragmatic myotrauma: A mediator of prolonged ventilation and poor patient outcomes in acute respiratory failure. Lancet Respir. Med. 2019, 7, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haaksma, M.E.; Atmowihardjo, L.; Heunks, L.; Spoelstra-De Man, A.; Tuinman, P.R. Ultrasound imaging of the diaphragm: Facts and future. A guide for the bedside clinician. Neth. J. Crit. Care 2018, 26, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Powers, S.K.; Shanely, R.A.; Coombes, J.S.; Koesterer, T.J.; McKenzie, M.; Van Gammeren, D.; Cicale, M.; Dodd, S.L. Mechanical ventilation results in progressive contractile dysfunction in the diaphragm. J. Appl. Physiol. 2002, 92, 1851–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knisely, A.; Leal, S.M.; Singer, D.B. Abnormalities of diaphragmatic muscle in neonates with ventilated lungs. J. Pediatr. 1988, 113, 1074–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaber, S.; Petrof, B.J.; Jung, B.; Chanques, G.; Berthet, J.-P.; Rabuel, C.; Bouyabrine, H.; Courouble, P.; Koechlin-Ramonatxo, C.; Sebbane, M.; et al. Rapidly Progressive Diaphragmatic Weakness and Injury during Mechanical Ventilation in Humans. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2011, 183, 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubé, B.-P.; Dres, M. Diaphragm Dysfunction: Diagnostic Approaches and Management Strategies. J. Clin. Med. 2016, 5, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dres, M.; Goligher, E.C.; Heunks, L.M.A.; Brochard, L.J. Critical illness-associated diaphragm weakness. Intensiv. Care Med. 2017, 43, 1441–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haaksma, M.E.; van Tienhoven, A.J.; Smit, J.M.; Heldeweg, M.L.; Lissenberg-Witte, B.I.; Wennen, M.; Jonkman, A.; Girbes, A.R.; Heunks, L.; Tuinman, P.R. Anatomical Variation in Diaphragm Thickness Assessed with Ultrasound in Healthy Volunteers. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2022, 48, 1833–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarlata, S.; Mancini, D.; Laudisio, A.; Raffaele, A.I. Reproducibility of diaphragmatic thickness measured by M-mode ultrasonography in healthy volunteers. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2019, 260, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-Esper, R.; Pérez-Calatayud, Á.A.; Arch-Tirado, E.; Díaz-Carrillo, M.A.; Garrido-Aguirre, E.; Tapia-Velazco, R.; Peña-Pérez, C.A.; Monteros, I.E.-D.L.; Meza-Márquez, J.M.; Flores-Rivera, O.I.; et al. Standardization of Sonographic Diaphragm Thickness Evaluations in Healthy Volunteers. Respir. Care 2016, 61, 920–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellyer, N.J.; Andreas, N.M.; Bernstetter, A.S.; Cieslak, K.R.; Donahue, G.F.; Steiner, E.A.; Hollman, J.H.; Boon, A.J. Comparison of Diaphragm Thickness Measurements Among Postures Via Ultrasound Imaging. Phys. Med. Rehabil. J. 2017, 9, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, M.; Pini, S.; Danzo, F.; Mirizzi, F.M.; Arena, C.; Tursi, F.; Radovanovic, D.; Santus, P. Ultrasonographic Assessment of Diaphragmatic Function and Its Clinical Application in the Management of Patients with Acute Respiratory Failure. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suttapanit, K.; Wongkrasunt, S.; Savatmongkorngul, S.; Supatanakij, P. Ultrasonographic evaluation of the diaphragm in critically ill patients to predict invasive mechanical ventilation. J. Intensiv. Care 2023, 11, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schepens, T.; Fard, S.; Goligher, E.C. Assessing Diaphragmatic Function. Respir. Care 2020, 65, 807–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, G.; De Filippi, G.; Elia, F.; Panero, F.; Volpicelli, G.; Aprà, F. Diaphragm ultrasound as a new index of discontinuation from mechanical ventilation. Ultrasound J. 2014, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiNino, E.; Gartman, E.J.; Sethi, J.M.; McCool, F.D. Diaphragm ultrasound as a predictor of successful extubation from mechanical ventilation. Thorax 2014, 69, 431–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farghaly, S.; Hasan, A.A. Diaphragm ultrasound as a new method to predict extubation outcome in mechanically ventilated patients. Aust. Crit. Care 2017, 30, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Spontaneous Inhalation | Positive Pressure Ventilation | |

|---|---|---|

| Intrapleural pressure | ↓ | ↑ |

| Venous return | ↑ | ↓ |

| Right ventricular stroke volume | ↑ | ↓ |

| Pulmonary vascular resistances | ↑ | ↑↓ * |

| Left ventricular stroke volume | ↓ | ↓ |

| Left ventricular afterload | ↑ | ↓ |

| Parameter | Evaluating | Pathologic Cutoff | How to | Pros | Cons | Tips |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RV diameters | RV dimension and relationship with LV | RVD1 (basal) > 41 mm RVD2 (medial) > 35 mm | A4C view end-diastole | Easy and rapid to obtain | Need for good acoustic window. Risk of overestimation when using a shorted image | It is useful to reduce the size of the ultrasound window to increase frames per second (FPS), sometimes it may be necessary to change the tilt of the ultrasound beam to improve the definition of the endocardial edges. |

| RV wall thickness | Index of RV hypertrophy | RVWT > 5 mm | Subcostal view, end-diastole | Easy and rapid to obtain | Subcostal view may be suboptimal in ventilated patients | Using zoom, measure at a distance from the tricuspid ring equal to the distance of the tricuspid anterior flap when it is fully open and parallel to the wall |

| IVS | Index of RV pressure or volume overload | Posterior displacement of the IVS towards the LV. Eccentricity index > 1. | SAX papillarymuscles view | No measure needed. Index of both volume and pressure overload | // | Sisto-diastolic D-shape points towards pressure overload (afterload increase) Only diastolic D-Shape points toward volume overload (es. Congenital heart disease). |

| FAC | Global RV systolic function | <35% | A4C view | Prognostic implication as indicator of RVSD | Time consuming, need for endocardial borders to been seen | It is useful to reduce the size of the ultrasound window to increase frames per second (FPS), sometimes it may be necessary to change the tilt of the ultrasound beam to improve the definition of the endocardial edges. |

| TAPSE, S’ | Longitudinal RV Systolic function | TAPSE < 18 mm S’ < 10 cm/s | A4C view | Prognostic implication as indicator of RVSD, Easy to obtain | May be lower after cardiac surgery, need for good ultrasound alignment | |

| sPAP | Index of RV afterload | TRV > 3.4 m/s PAPs > 40 mmHg | A4C view, PLAX view (anterior probe tilt), SAX view | If TR is more than trivial: easy to obtain, Useful for assessment of afterload changes over time and therefore adjusting PEEP and PS therapy | May be underestimated in severe TR or RVSD, May be difficult to obtain in trivial TR | Need for good ultrasound alignment |

| TAPSE/sPAP ratio | Index of RV arterial-ventricular coupling | TAPSE/PAPs < 0.5 mm/mmHg * | See above | Prognostic implication, see above TAPSE and sPAP | Combination of pitfalls for TAPSE and PAPs. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Delle Femine, F.C.; D’Arienzo, D.; Liccardo, B.; Pastore, M.C.; Ilardi, F.; Mandoli, G.E.; Sperlongano, S.; Malagoli, A.; Lisi, M.; Benfari, G.; et al. Echocardiography in the Ventilated Patient: What the Clinician Has to Know. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14010077

Delle Femine FC, D’Arienzo D, Liccardo B, Pastore MC, Ilardi F, Mandoli GE, Sperlongano S, Malagoli A, Lisi M, Benfari G, et al. Echocardiography in the Ventilated Patient: What the Clinician Has to Know. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(1):77. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14010077

Chicago/Turabian StyleDelle Femine, Fiorella Chiara, Diego D’Arienzo, Biagio Liccardo, Maria Concetta Pastore, Federica Ilardi, Giulia Elena Mandoli, Simona Sperlongano, Alessandro Malagoli, Matteo Lisi, Giovanni Benfari, and et al. 2025. "Echocardiography in the Ventilated Patient: What the Clinician Has to Know" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 1: 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14010077

APA StyleDelle Femine, F. C., D’Arienzo, D., Liccardo, B., Pastore, M. C., Ilardi, F., Mandoli, G. E., Sperlongano, S., Malagoli, A., Lisi, M., Benfari, G., Russo, V., Cameli, M., & D’Andrea, A., on behalf of the Working Group in Echocardiography of the Italian Society of Cardiology. (2025). Echocardiography in the Ventilated Patient: What the Clinician Has to Know. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(1), 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14010077