Evaluating Behavioural Interventions for Oropharyngeal Dysphagia in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Swallowing Manoeuvres, Exercises, and Postural Techniques †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Information Sources

2.2. Search Strategies

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

2.4. Systematic Review

2.5. Meta-Analysis

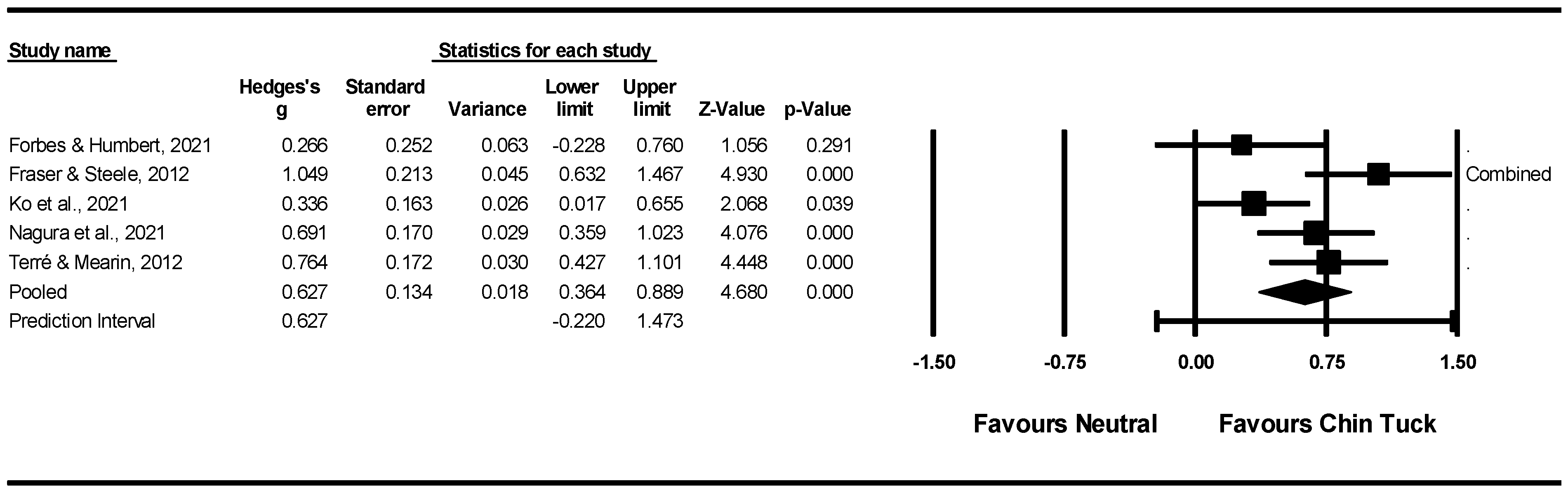

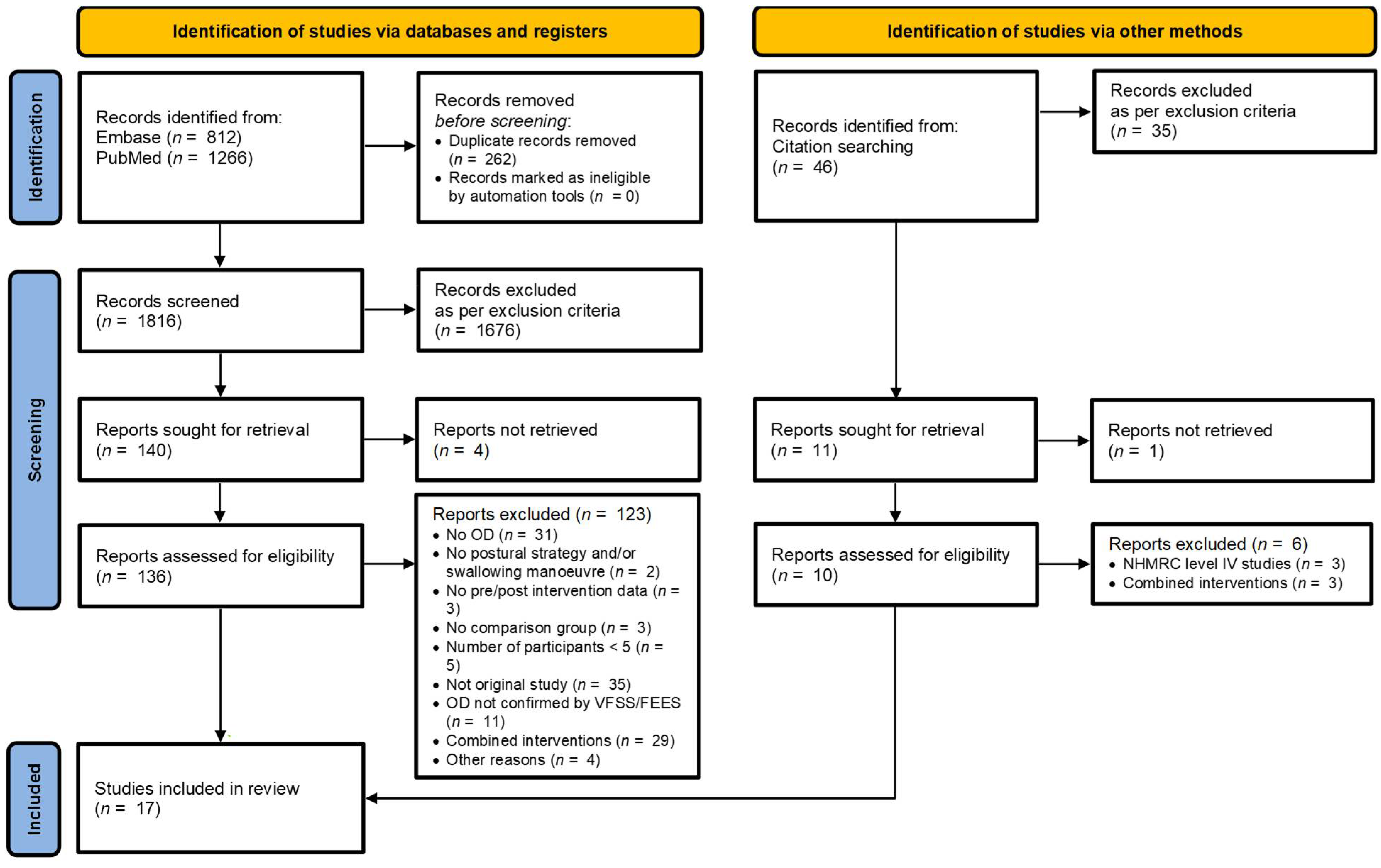

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Description of Studies

Author, Year

|

| Sample (N) Groups c (n) | Group Descriptives (e.g., Age, Gender, Medical Diagnoses) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Archer et al., 2021 [39] UK II Strong: 90% |

| N = 13 (stroke patients) N = 17 (healthy controls) (crossover study design, random allocation): - Condition 1: ES - Condition 2: ES + biofeedback | Demographics Age (yrs): Median (IQR) Gender (nM/nF) FOIS: Median (IQR) PAS: Median (IQR) | Group Stroke * 74.5 (61.3–83.3) 9/5 4.0 (1.0–5.0) 7.5 (5.3–8.0) | Group Healthy controls 76 (74.5–81.5) 10/7 N/A N/A | ||

| * Prior to participant drop-out (n = 14): R MCA infarct (5); L MCA infarct (3); other (6) | |||||||

| Don Kim et al., 2015 [66] Republic of Korea II Good: 71% |

| N = 26 (stroke patients, random allocation):

| Demographics Age (yrs): Mean ± SD After onset (months): Mean ± SD Gender (nM/nF) Side (R/L) * Inconsistency in reporting sample size | Group 1 63.6 ± 8.1 16.15 ± 3.1 7/8 * 7/6 | Group 2 63.2 ± 10.2 15.6 ± 2.9 8/5 7/6 | ||

| Forbes & Humbert, 2021 [67] USA III-2 Strong: 91% |

| N = 15 (patients with OD of mixed aetiology, retrospective study). N = 62 paired swallows * categorized to:

* Real-time clinical judgments of bolus depth relative to swallow onset contributed to aberrant bolus flow and served as reasons for chin-down posture. | Demographics Age (yrs): Mean ± SD | Group 58.0 ± 18.0 | |||

| Medical diagnoses (n = 15): cerebrovascular accident (5), unknown (2), coronary artery disease, recurrent urinary tract infection and chronic kidney disease (1); Karlengener’s syndrome, cancer, and base of tongue radiation (1); neurofibroma and transoral resection (1); open valve replacement complication by intubation resulting in injury (1); right laryngocele surgery (1); spinal surgery for cervical fusion (1); surgery for osteophytes (1); vocal cord paralysis (1). | |||||||

| Fraser & Steele, 2012 [68] Canada III-1 Strong: 82% |

| N = 42

N = 98 (VFSS swallows: de-identified and randomised for rating) categorised to:

| Demographics Age (yrs): Mean (Range) After stroke onset: Gender (nM/nF) | Group 1 73 (49–87) 2 week(s)–18 month(s) 9/7 | Group 2 * 77 (39–92) N/A 14/12 | ||

| Medical diagnoses *: multiple sclerosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), kidney disease, fractures, congestive heart failure, diabetes, sepsis, Wilson’s disease, and gastrointestinal disease. NB. Aetiology factor removed from analyses (as no significant group differences for frequency of airway invasion) | |||||||

| Gomes et al., 2020 [69] Brazil III-2 Good: 77% |

| N = 22 (patients with neurogenic OD [Parkinson: n = 14; stroke: n = 8], same participants) categorised to:

| Demographics Age (yrs): Mean ± SD (Range) Gender (nM/nF) | Group 66.24 ± 9.53 (52–89) * PD 6/8, Stroke 7/1 | |||

| * Data from supplementary material. Manuscript abstract reports age range 41–75 years. | |||||||

| Heslin & Regan, 2022 [70] Ireland III-2 Strong: 86% |

| N = 15 (patients with OD of mixed aetiology, same participants) categorised to:

| Demographics Age (yrs): Mean (Range) Gender (nM/nF) | Group 63.0 (45–86) 8/7 | |||

| Medical diagnoses (N = 15): stroke (3), achalasia (1), multiple sclerosis (2), respiratory failure (1), unknown (2), autoimmune disease (1), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (1), gastroesophageal reflux disease (1), lung cancer (1), motor neuron disease (2) | |||||||

| Ko, Shin et al., 2021 [71] Republic of Korea III-2 Strong: 95% |

| N = 76 (adults with OD of mixed aetiology, retrospective study, same participants) categorised to:

| Demographics * Age (yrs): Mean ± SD Gender (nM/nF) | Group (n = 26) Effective Chin tuck 65.62 ± 17.66 14/12 | Group (n = 50) Ineffective Chin tuck 68.22 ± 12.19 29/21 | ||

| Medical diagnoses (n = 76): stroke (31), idiopathic (25), traumatic brain injury (8), Parkinson’s disease (3), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (1), dermatomyositis (1), chronic subdural haemorrhage (1), hypoxic brain damage (1), epilepsy (1), laryngeal cancer (1), meningitis (1), polymyositis (1), tonsillar cancer (1) * Total group (N = 76): N/R | |||||||

| Koyama et al., 2017 [72] Japan II Strong: 100% |

| N = 16 (stroke patients, random allocation):

* Excluding lost to follow-up: n = 2 (for each group) | Demographics Age (yrs): Mean ± SD Gender (nM/nF) Post onset (week[s]) Stroke location: Supra/Infratentorial Lesion: Multiple/Single | Group 1 66.0 ± 9.3 5/1 6.7 (2.1) 1/5 2/4 | Group 2 71.8 ± 7.6 5/1 9.2 (4.0) 1/5 1/5 | ||

| Kumai et al., 2021 [63] Japan III-2 Strong: 91% |

| N = 7 (MG patients, same participants) categorised to:

| Demographics Age (yrs): Mean (Range) Gender (nM/nF) MGFA clinical classification * QMG **: Mean (Range) Oral intake | Group 52.6 (35–74) 6/1 IIa (1), IIb (4), IIIb (1), IVa (1) 15.0 (10–28) Regular diet 5/7; Soft diet 2/7 | |||

| * Score: I (any muscular weakness) to IV (severe muscular weakness) ** Quantitative Myasthenia Gravis score (total and neck muscles alone) | |||||||

| McCullough & Kim, 2012 [40] USA II Good: 79% |

| N = 18 (stroke patients, crossover study design, random allocation):

| Demographics Age (yrs): Mean (Range) Gender (nM/nF) Post-stroke: Mean (Range) | Total group (Group 1 + 2) 70.2 (42–88) 11/7 9.5 months (6 weeks–22 months) | |||

| McCullough & Kim, 2013 [43] USA II Good: 75% |

| As per McCollough 2012. | As per McCollough 2012. | ||||

| Miyamoto et al., 2021 [76] Japan III-2 Good: 75% |

| N = 64 (patients with OD of mixed aetiology, retrospective study, same participants) categorized to:

| Demographics Age (yrs) Gender (nM/nF) | Group N/R N/R | |||

| Medical diagnoses (n = 64): head and neck (26), digestive disorder (20), neuromuscular disorder (12), other (6) | |||||||

| Nagura et al., 2022 [73] Japan III-2 Strong: 82% |

| N = 73 (patients with OD of mixed aetiology, retrospective study, same participants) categorized to:

| Demographics Age (yrs): Mean ± SD Gender (nM/nF) DSS *: level (n) | Group 67 ± 14 56/41 2 (4), 3 (39), 4 (28), 5 (1), 6 (1) | |||

| Medical diagnoses (n = 73): stroke (33), cancer (13), respiratory disease (10), neuromuscular disease (6), others (11) * Levels 1–4: aspiration (saliva, food, water, occasional), Levels 5–7: without aspiration (oral problems, minimum problems, within normal limits) | |||||||

| Ra et al., 2014 [64] Republic of Korea III-2 Strong: 91% |

| N = 97 (patients with OD of mixed aetiology dysphagia, same participants) categorized to:

| Demographics Age (yrs): Mean ± SD Gender (nM/nF) | Group Total group (n = 97) 67.1 ± 13.7 56/41 | Group (n = 19) Effective Chin tuck (EFF) 64.1 ± 17.7 6/13 | Group (n = 78) Ineffective Chin tuck (INEFF) 67.8 ± 12.6 50/28 | |

| Medical diagnoses (n = 97): stroke (59), traumatic brain injury (10), Parkinson’s disease (4), Guillain-Barre syndrome (2), vocal cord palsy (2), hypoxic brain damage (2), myasthenia gravis (1), hypopharyngeal cancer (1), brain metastasis of lung cancer (1), bacterial meningitis (1), unknown (14) | |||||||

| Shaker et al., 2002 [75] USA II Strong: 89% |

| N = 27 * (random allocation):

* Following clinical observation that patients significantly improved in Group 1 (head-raising exercise) but not in Group 2 (sham exercise), no further participants were allocated to the sham group. Additional patients were enrolled in Group 1. Ultimately, all 27 participants completed the head raising exercise protocol, with 7 patients completing the sham exercise prior to participating in the head raising exercise protocol. | Demographics Age (yrs): Median (Range) Gender (nM/nF): Duration of dysphagia (days): Mean (Range) | Total group (N = 27) 74 (62–89) 25/2 259 (9–2880) | |||

| Terré & Mearin, 2012 [74] Spain II Good: 71% |

| N = 72 (patients with neurogenic OD [stroke: n = 45; TBI: n = 27], crossover study design comparing chin-down vs. no chin-down posture, random allocation):

| Demographics Age (yrs): Mean (Range) Gender (nM/nF) Stroke/TBI (n) | Group 1 43 (18–75) 31/16 31/16 | Group 2 51 (21–76) 19/6 14/11 | ||

| Vose et al., 2019 [65] USA II Strong: 82% |

| N = 19? * (volitional laryngeal vestibule closure [vLVC] manoeuvre using three different biofeedback modalities, random allocation):

* Inconsistencies reporting sample sizes. Original sample size N = 21. Lost to follow-up (n = 3) due to failure to demonstrate vLVC manoeuvre (Group 2: n = 2; Group 3 n = 1). | Demographics Age (yrs): Mean ± SD Gender (nM/nF) Type of stroke (n) | Total group (N = 19?) 58 ± 18 13/6 ischemic (7); hemorrhagic (7); embolic (4); TIA (1) | |||

| Author, Year | Intervention Goals | Intervention Delivery and Dosage a | Materials and Procedures a | Outcome Measures | Treatment Outcomes a (Main Outcome According to Authors) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Archer et al., 2021 [39] | To determine: (1) if age or stroke-related dysphagia affects the ability to increase submental muscle activity during ES compared to normal swallowing; (2) if sEMG biofeedback improves the performance of ES by healthy and dysphagic stroke participants; (3) if participants find sEMG comfortable, helpful and acceptable. | Intervention agent sEMG biofeedback and swallow task training provided by researchers. Delivery/Dosage 2 sessions completed within 1 week, but >24 h apart. Each session consisted of 3 NS and 6 ES tasks repeated twice, with a 5 min rest. Two conditions: with and without biofeedback. Swallows were facilitated by 5 mL water bolus, with 30 s rests b/w each. | Summary: ES (with or without biofeedback) vs. normal swallowing (NS) in stroke vs. healthy participants. All participants followed the same procedure: they were instructed to perform ES with the command “Swallow hard, squeezing all of your throat muscles and pushing hard with your tongue on the roof of your mouth”. For the NS participants were told to “Swallow in your normal way”. Each participant received a 5 mL water bolus from a teaspoon and was instructed to hold water in their mouth until prompted to swallow. If there was a high risk of aspiration, accommodations (e.g., consistency modification or moistened mouthcare swabs) were made, with the same bolus type used across sessions. Participants were randomly exposed to either: “with biofeedback followed by without biofeedback” or “without biofeedback followed by with biofeedback”. EMG biofeedback condition: participants saw the Digital Swallow Workstation (DSW) screen while performing swallowing tasks and were verbally encouraged to increase the strength of each ES using visual targets to “beat” (cursors placed on their previous attempt). No additional instruction was given for NS. Non-biofeedback condition: participants did not see the DSW screen and were verbally encouraged to swallow “harder” during ES. | Primary outcomes Submental muscle activity - sEMG amplitudes. Secondary outcomes Comfort, utility and acceptability of sEMG biofeedback—questionnaire with 8 questions about participant impression of completing the ES with and without sEMG biofeedback. | Primary outcomes

ES is a physiologically beneficial dysphagia exercise that enhances muscle activity during swallowing, with sEMG biofeedback further improving performance and being well-tolerated by patients. |

| Don Kim et al., 2015 [66] | To examine the effects of short neck flection exercises using PNF on the swallowing function of stroke patients with dysphagia. | Intervention agent 2 experienced PTs (Physical therapists) Delivery/Dosage Group 1 (isometric, isotonic Shaker exercises): 3 days a week for 30 min. each time over a period of 6 weeks. Group 2 (PNF-based short neck flexion exercises): 3 days a week for 30 min each time over a period of 6 weeks. | Summary: PNF-based short neck flexion exercise vs. (isometric/isotonic) Shaker exercise in stroke patients. Group 1: (a) Isometric Shaker exercise: patients lay on a bed, raised their heads without moving their shoulders, and looked at the ends of their feet for 60 s, then lowered their heads back on the bed and rested for 60 s. If a patient struggled, they performed the exercise for as long as possible, repeating it 3x. (b) Isotonic Shaker exercise: patients raised their heads in the same posture and looked at the ends of their feet for 30 consecutive repetitions. If unable to complete 30, fewer repetitions were allowed. Group 2: PNF-based short neck flection exercises: Patients lie on a bed with their heads and necks off the edge. A tester, positioned on the left side behind the patient’s head, supports the patient’s left laryngeal region with his right hand and places his left fingertips below the patient’s jaw. Patients are instructed to look at a target object 15° diagonally to the right. The tester moves the patient’s neck diagonally in the opposite direction, instructing them to: “draw your jaw inward” while applying resistance to the jaw to activate the neck flexors (performing external cervical flexion). The patient performs cervical flexion or right-side rotation. If the patient struggles, the tester provides light support instead of resistance to help complete the exercise. The exercises are repeated in the opposite direction. | Primary outcomes VFSS - New VFSS scale - ASHA NOMS scale (American Speech-Language-Hearing Association National Outcomes Measurement System scale) | Primary outcomes

|

| Forbes & Humbert, 2021 [67] | To examine the impact of chin-down on swallowing physiology in patients with various medical conditions and swallowing impairments. To determine: (1) if swallowing kinematics are affected by chin-down; (2) if chin-down improves airway protection and bolus efficiency. | Intervention agent practising clinician Delivery/Dosage 1–2 VFSS sessions | Summary: Chin down posture vs. neutral head position in OD patients of mixed aetiology (same participants). VFSS examination: Neutral head position (no chin down) or chin-down (if physiologically necessary in aberrant bolus flow). Swallowed bolus: 5 mL of room-temperature thin liquid barium, at least one swallow in both positions. The number of swallows: 1–5 per patient. Areas visualised: oral cavity, velum, pharynx, hyoid bone, larynx, UES, cervical esophagus, and cervical vertebrae. | Primary outcomes VFSS

| Primary outcomes

Chin-down posture inconsistently prevented the presence of penetration and aspiration within and across patients. |

| Fraser & Steele, 2012 [68] | To study the impact of the chin down on swallowing safety (penetration and aspiration) in a general acute care patient population (stroke and general internal medicine). | Intervention agent SLP Delivery /Dosage Single session VFSS | Summary: Chin down position vs. head neutral position with two bolus administrations (teaspoon/cup-sip) in 2 groups of patients (stroke, general internal medicine -GIM). VFSS examination: 1. In head neutral position (no chin down); a teaspoon of thin liquid barium was swallowed; 2. If penetration/aspiration occurred, chin down (by tucking the head downward, “looking down to the knees”) and the same bolus volume was given; 3. If no issues are found, proceed to the cup-drinking task with a thin liquid barium in a neutral head position (with the chin up); 4. If penetration/aspiration occurs, the chin is down, and the same bolus is administered from a cup. VFSS completed. VFSS recordings captured with the image field from the lips to the upper esophagus. | Primary outcomes VFSS

| Primary outcomes

|

| Gomes et al., 2020 [69] | To evaluate the effects of ES on cardiac autonomic control (heart rate variability—HRV) in subjects with neurogenic OD. | Intervention agent N/R Delivery/Dosage Spontaneous swallow: 5 min at rest, 3 spontaneous swallows of saliva every 1 min and 30 s. ES: 3 ESs, each one in 1 min and 30 s during 5 min. | Summary: ES vs. spontaneous swallow in neurogenic OD patients (same participants). ES training protocol: Involved 3 ES (tongue force on the palate), each lasting 1 min and 30 s, performed during 5 min. Experimental procedures: Split into two randomised stages, via card allotments on the same day: (a) Spontaneous swallowing: Subjects rested for 5 min, then performed 3 spontaneous swallows of saliva on command every 1 min 30 s, with additional swallowing as needed. (b) ES: After the initial 5 min, subjects performed the training ES for an additional 5 min, completing 3 ES every 1 min 30 s, as directed. HRV: Compared between spontaneous swallowing and the ES protocol. | Primary outcomes HRV analysis

sEMG (Surface electromyographic) evaluation | Primary outcomes

Swallowing parameters (HRV analysis) showed no clinically significant changes in autonomic heart rate control during ES in subjects with OD. |

| Heslin & Regan, 2022 [70] | To quantify the effects of ES on pharyngeal swallowing biomechanics in adults with OD using pharyngeal high-resolution manometry (PHRM). | Intervention agent Clinical SLP Delivery/Dosage Single session HRM | Summary: ES vs. non-ES swallow in mixed aetiology OD patients (same participants, randomised order of condition). ES procedure: 2 × 10 mL liquid boluses administered via 20 mL syringe and swallowed under two conditions: non-ES (control) and ES. Verbal cues prior to each trial: “swallow as normal” and “squeeze hard with all your muscles as you swallow” (ES). Where post-swallow piecemeal deglutition and coughing occurred, a trial was repeated. Minimum 30 s period between swallows was enforced to prevent inhibition of esophageal peristalsis. | Primary outcomes High-resolution manometry (HRM)

| Primary outcomes Significantly increased metrics during ES vs. non-ES:

ES significantly increased global pharyngeal contractility during swallowing thin liquids in adults with OD, supporting that ES generates higher pharyngeal pressure than non-ES. |

| Ko, Shin et al., 2021 [71] | To investigate, via VFSS, the effect of the chin tuck on the severity of penetration. | Intervention agent Physiatrist experienced in VFSS analysis Delivery/Dosage Single session VFSS | Summary: Comparison of chin tuck vs. head neutral position in mixed aetiology OD patients (same participants, retrospective study). VFSS examination: 3 mL boluses in the following order: 3 × thick liquid (International Dysphagia Diet Standardisation Initiative—IDDSI 3); 2 × Rice porridge (IDDSI 2); 2 × curd yogurt (IDDSI 1); 3 × thin liquid (IDDSI 0); 2 × 5 mL of thin liquid from a cup. If penetration occurred in the head neutral position, the patient performed the chin tuck manoeuvre (“tuck chin as close to sternum as possible”), with the same consistency and volume. Repeat if the chin tuck posture was incorrect. VFSS analysis: Selected frames showing deepest penetration, with contrast visible between the laryngeal inlet and vocal fold. Measurements conducted using ImageJ®® software. The Chin tuck manoeuvre is considered effective if the penetration severity is reduced by at least one grade. | Primary outcomes VFSS

| Primary outcomes

|

| Koyama et al., 2017 [72] | To verify the feasibility of MJOE and its effectiveness in promoting anterior displacement of the hyoid bone during swallowing in stroke patients with OD. | Intervention agent: MJOE trainer (not specified). Delivery/Dosage Group 1 (MJOE): maintain 80% maximum voluntary contraction (MVC) for 6 s, 5x repetitions (1 set), 4 sets/day, 5x/week, 6 weeks total, 6 weeks resistive load Group 2 (Sham exercise): 20% MVC for 6 s, 5x repetitions (1 set), 4 sets/day, 5 x/week, 6 weeks total, 6 weeks resistive load | Summary: MJOE vs. Sham exercise in stroke patients. Group 1 (MJOE): Surface electrodes on SHMs at the mandibular midline, connected to biofeedback equipment. Participants were asked to close their mouths in a comfortable sitting position, with the front half of their tongues pressed against the hard palate. The trainer placed a hand under the participant’s chin and applied upward vertical resistance. Visual feedback was provided on the intensity of the isometric opening movement of the mandible (mouth closed, front half of tongue pressed against the hard palate). Participants were instructed to maintain 80% MVC during exercise. Group 2 (Sham exercise: Isometric jaw closing exercise): Surface electrodes attached to the masseter muscle and connected to biofeedback equipment. Participants were given visual feedback on the intensity of the isometric closing movement of the mandible (jaw occluded in a comfortable sitting position); then instructed to maintain 20% MVC during exercise. Discontinuance criteria: pain in the TMJ (Temporomandibular Joint) and/or anterior region of the neck during exercise. | Primary outcomes VFSS

VFSS

| Primary outcomes

MJOE is feasible without any adverse events in poststroke patients, and it promotes anterior HD during swallowing. |

| Kumai, Miyamoto et al., 2021 [63] | To compare oropharyngeal swallowing dysfunction in MG patients with difficulty in swallowing between the neutral and chin-down positions using high-resolution manometry (HRM). | Intervention agent N/R Delivery/Dosage Single session HRM | Summary: Chin-down vs. head neutral positions in MG patients (same participants). HRM examination: Patients examined at the same time period (4–6 PM). HRM utilized to identify each portion in typical pressure topography data. Representative data from MG patients with mild to moderate OD were assessed in both conditions: head neutral position and chin-down position. Averaged data over 3 swallows: maximum SP at velopharynx, meso–hypopharynx, and UES, and duration of UES relaxation pressure. | Primary outcomes HRM parameters:

| Primary outcomes

The chin-down position appears useful for improving pharyngeal clearance in MG patients, by promoting increased SP at the meso–hypopharynx, relaxing SP at the UES, and increasing the duration of UES relaxation. |

| McCullough et al., 2012 [40] | To determine any lasting changes in swallowing physiology following intensive exercise using the Mendelsohn Manoeuvre in stroke patients with dysphagia. | Intervention agent: Principal investigator with some support from the study clinician. Delivery/Dosage: Twice daily sessions, 45–60 min, with a 2–3 h break b/w sessions, 2 weeks total. | Summary: Mendelsohn manoeuvre vs. no treatment in stroke patients (crossover study design) Treatment sessions: Participants were taught the Mendelsohn manoeuvre (squeezing and holding the larynx at the peak of the swallow) using surface electromyography (sEMG) feedback. Non-adjustable, ground, and active electrode pads placed submentally at the midline, halfway b/w the mental symphysis and the hyoid bone tip. Tracings were used to provide participant biofeedback. Before each swallow, dental swabs dipped in ice water were used to moisten the mouth, facilitating swallowing. Clinician feedback—video information provided to participants included onset/offset points, swallow duration, peak amplitude (from Prometheus software) and comparisons of duration to the previous swallow. Aimed for 40 swallows but stopped after a minimum of 30 if discomfort occurred. | Primary outcomes VFSS

VFSS

| Primary outcomes

Intensive use of the Mendelsohn manoeuvre altered the duration of hyoid movement and UES opening. |

| McCullough & Kim, 2013 [43] | To determine the effects of the Mendelsohn manoeuvre on the distance the hyoid travels superiorly and anteriorly, and the impact on the mean width of the UES opening in stroke patients with dysphagia. | Secondary data analysis of McCullough 2012. | Secondary data analysis of McCullough 2012. | Primary outcomes VFSS

| Primary outcomes

After Mendelsohn manoeuvre training, gains were demonstrated in the extent of hyoid movement and UES opening, as well as improvements in the coordination of structural movements with each other and with bolus flow. |

| Miyamoto, Kumai et al., 2021 [76] | To evaluate pharyngeal swallowing to determine the characteristics of OD (pathophysiology and type of disease) that respond positively to the chin-down and help prevent aspiration. | Intervention agent: 3 expert SLPs Delivery/Dosage: Single session VFSS | Summary: Comparison of chin-down vs. head-neutral position in mixed aetiology OD patients (same participants, randomised order of condition). VFSS examination: 3 × 3 mL bolus of barium sulphate 120 w/v% (<30 s time intervals between swallows) in both positions: head neutral position and chin-down (“neck flexion” position, the neck flexed at the level of the lower cervical spine). For high-risk aspiration patients (PAS 7–8), swallowing was performed once. | Primary outcomes VFSS

| Primary outcomes

Insufficient laryngeal closure due to inadequate laryngeal elevation is the pathophysiology most likely to respond favourably to the chin-down manoeuvre. |

| Nagura, Kagaya et al., 2022 [73] | To assess the effects of head flexion posture in patients with dysphagia of mixed aetiology. | Intervention agent: Research technician experienced in image analysis Delivery/Dosage: Single session VFSS | Summary: Head flexion posture vs. without head flexion posture in mixed aetiology OD patients (same participants, retrospective study). VFSS examination: Head flexion posture (“Bring the chin as close as possible to the neck without flexing the neck”); no head flexion posture. Evaluation of biomechanical aspects of swallowing, including timing of swallow and head and neck flexion angles. Thickness and amount of contrast material were changed according to the patient’s condition (same type and amount of bolus for both postures); bolus consistency: thin liquid (n = 45) and thick liquid (n = 28); bolus volume: 4 mL (n = 44) and 10 mL (n = 19); Position: sitting (n = 66) and at 75°, 60°, and 45° angles from the supine position (n = 1, 5 and 1, respectively). | Primary outcomes VFSS

| Primary outcomes Statistically significant changes for head flexion compared to no head flexion:

N/S changes for remaining outcome variables. Head flexion posture resulted in earlier laryngeal closure and a shallower position of the leading bolus edge at the swallowing reflex, leading to PAS improvement and decreased aspiration. |

| Ra et al., 2014 [64] | To identify factors affecting the efficiency of the chin tuck and determine the optimal neck flexion angle in chin tuck in patients with OD of mixed aetiology. | Intervention agent: Physiatrist experienced in VFSS analysis Delivery/Dosage: Single VFSS session. | Summary: Comparison of chin tuck vs. head neutral position in mixed aetiology OD patients (same population). VFSS examination: Head neutral position: 5 × 5 mL thin bolus barium. Chin tuck pose (flexion of the head as much as possible, touching the chin to the chest) in case of penetration/aspiration: repeat 5 × 5 mL same bolus. | Primary outcomes VFSS

| Primary outcomes Chin tuck vs. head neutral:

Chin tuck might be less effective in those who have excessive residue in the pyriformis sinus. Sufficient neck flexion is important: the required minimum neck flexion is 17.5° for benefitting from the chin tuck. |

| Shaker et al., 2002 [75] | To evaluate the effect of the head-raising exercise on the deglutitive biomechanical events and functional outcome of swallowing in patients with deglutitive failure due to abnormal UES opening, necessitating PEG (Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy). | Intervention agent: SLP Delivery/Dosage: 3 x/day × 6 weeks | Summary: Head-raising vs. Sham exercise in pharyngeal dysphagia. Group 1 (Head-raising exercise protocol): Lie flat and perform 3 sustained head raisings for 1 min in the supine position, with a 1 min rest period. Followed by 30 consecutive repetitions of head raising in the same position (raise head enough to observe toes without raising shoulders). Group 2 (Sham protocol): 15 repetitions of passive tongue lateralisation. | Primary outcomes VFSS

| Primary outcomes

A suprahyoid muscle strengthening exercise program is effective in restoring oral feeding in some patients with deglutitive failure because of abnormal UES opening. |

| Terré & Mearin, 2012 [74] | To assess the effectiveness of the chin-down posture to prevent aspiration in neurogenic dysphagia patients secondary to acquired brain injury (stroke and trauma). | Intervention agent: Researcher Delivery/Dosage: Single VFSS session. | Summary: Chin-down vs. no chin-down in neurogenic dysphagia patients, with or without aspiration (crossover study). VFSS examination: no chin-down (cervical rachis in the anatomic position); chin-down (cervical rachis in flexion with sterno-mental contact). Evaluated biomechanical swallow with 3, 5, 10, and 15 mL boluses of pudding, nectar, and liquid consistencies in both positions. Swallowing sequences were recorded; oral and pharyngeal function was assessed for all viscosities and volumes, including cricopharyngeal dysfunction and pharyngeal residue where applicable. Examination discontinued if the patient aspirated or was unable to cooperate. | Primary outcomes VFSS

| Primary outcomes

|

| Vose et al., 2019 [65] | To compare the effect of 3 visual biofeedback conditions (ssEMG; VF, mixed VF + ssEMG) on swallowing airway protection accuracy when training the vLVC (volitional laryngeal vestibule closure) swallowing manoeuvre in poststroke patients with dysphagia, and to examine clinician accuracy in judging vLVC performance. | Intervention agent: Experienced clinicians. Delivery/Dosage: Maximum of 20 saliva and 40 bolus swallows. Saliva swallows: 3 s in duration for 3 swallows, increased by 1 s up to a maximum of 6 s (where possible, dependent on patient tolerance and fatigue). Rest periods approx. 10 s. Bolus swallows followed same pattern. | Summary: vLVC using three types of biofeedback (ssEMG, VF and mixed) in stroke patients. Phase 1—Accurate demonstration of vLVC Manoeuvre: clinician provided instructions and demonstration of vLVC manoeuvre. Participants performed the exercise to feel superior movement during a saliva swallow, focusing on differences in hyolaryngeal elevation duration. Next, they were instructed to swallow and hold their thyroid notch up as high and as long as possible during swallowing, and to ensure that they could not breathe during the manoeuvre, given closure of the vestibule. Phase 2—vLVC Manoeuvre training: A series of saliva vLVC swallows followed by bolus vLVC swallows, using ssEMG, VF, or combination (Mixed). Participants viewed the vLVC in a normal saliva swallow in real-time. They were then instructed to perform the vLVC manoeuvre while watching real-time ssEMG/VF. The clinician provided verbal cues in real time.

| Primary outcomes VFSS

| Primary outcomes

Both the accuracy of vLVC training performance and clinician feedback were poorer in the ssEMG group (1) compared to the VF group (2) and mixed groups (3). |

3.3. Methodological Quality

3.4. Effect of Interventions

4. Discussion

4.1. Swallowing Manoeuvres, Exercises and Postural Strategies

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Keeney, S.; Hasson, F.; McKenna, H.P. A critical review of the Delphi technique as a research methodology for nursing. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2001, 38, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Speyer, R.; Cordier, R.; Denman, D.; Windsor, C.; Krisciunas, G.P.; Smithard, D.; Heijnen, B.J. Development of Two Patient Self-Reported Measures on Functional Health Status (FOD) and Health-Related Quality of Life (QOD) in Adults with Oropharyngeal Dysphagia Using the Delphi Technique. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 5920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steele, C.M.; Alsanei, W.A.; Ayanikalath, S.; Barbon, C.E.; Chen, J.; Cichero, J.A.; Coutts, K.; Dantas, R.O.; Duivestein, J.; Giosa, L.; et al. The influence of food texture and liquid consistency modification on swallowing physiology and function: A systematic review. Dysphagia 2015, 30, 2–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roden, D.F.; Altman, K.W. Causes of dysphagia among different age groups: A systematic review of the literature. Otolaryngol. Clin. North Am. 2013, 46, 965–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kertscher, B.; Speyer, R.; Fong, E.; Georgiou, A.M.; Smith, M. Prevalence of oropharyngeal dysphagia in the Netherlands: A telephone survey. Dysphagia 2015, 30, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takizawa, C.; Gemmell, E.; Kenworthy, J.; Speyer, R. A Systematic Review of the Prevalence of Oropharyngeal Dysphagia in Stroke, Parkinson’s Disease, Alzheimer’s Disease, Head Injury, and Pneumonia. Dysphagia 2016, 31, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, T.-N.; Ho, W.-C.; Wang, L.-H.; Chang, F.-C.; Nhu, N.T.; Chou, L.-W. Prevalence and Methods for Assessment of Oropharyngeal Dysphagia in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miarons Font, M.; Rofes Salsench, L. Antipsychotic medication and oropharyngeal dysphagia: Systematic review. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 29, 1332–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivelsrud, M.C.; Hartelius, L.; Bergström, L.; Løvstad, M.; Speyer, R. Prevalence of Oropharyngeal Dysphagia in Adults in Different Healthcare Settings: A Systematic Review and Meta-analyses. Dysphagia 2023, 38, 76–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, I.; Hamad, A.; Sasegbon, A.; Hamdy, S. Advances in the Treatment of Dysphagia in Neurological Disorders: A Review of Current Evidence and Future Considerations. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2022, 18, 2251–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, P.; Steele, C.M. Effectiveness of Interventions for Dysphagia in Parkinson Disease: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Speech-Lang. Pathol. 2022, 31, 463–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groher, M.E.; Crary, M.A. Dysphagia: Clinical Management in Adults and Children; Mosby Elsevier: Maryland Heights, MO, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Speyer, R.; Cordier, R.; Sutt, A.L.; Remijn, L.; Heijnen, B.J.; Balaguer, M.; Pommée, T.; McInerney, M.; Bergström, L. Behavioural Interventions in People with Oropharyngeal Dysphagia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Clinical Trials. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueha, R.; Cotaoco, C.; Kondo, K.; Yamasoba, T. Management and Treatment for Dysphagia in Neurodegenerative Disorders. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 13, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belafsky, P.C. Dilation of the Upper Esophageal Sphincter. Foregut 2024, 4, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotaoco, C.; Ueha, R.; Koyama, M.; Sato, T.; Goto, T.; Kondo, K. Swallowing improvement surgeries. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2024, 281, 2807–2817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jandee, S.; Geeraerts, A.; Geysen, H.; Rommel, N.; Tack, J.; Vanuytsel, T. Management of Ineffective Esophageal Hypomotility. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 638915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.K.; Park, C.-S.; Kim, J.W.; Hwang, K.; Lee, S.Y.; Kim, T.H.; Park, D.-Y.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, D.-Y.; Lee, H.J.; et al. Guidelines for the Antibiotic Use in Adults with Acute Upper Respiratory Tract Infections. Infect. Chemother. 2017, 49, 326–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler-Hegland, K.; Ashford, J.; Frymark, T.; McCabe, D.; Mullen, R.; Musson, N.; Hammond, C.S.; Schooling, T. Evidence-based systematic review: Oropharyngeal dysphagia behavioral treatments. Part II--impact of dysphagia treatment on normal swallow function. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 2009, 46, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azzolino, D.; Damanti, S.; Bertagnoli, L.; Lucchi, T.; Cesari, M. Sarcopenia and swallowing disorders in older people. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2019, 31, 799–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baijens, L.W.; Clavé, P.; Cras, P.; Ekberg, O.; Forster, A.; Kolb, G.F.; Leners, J.C.; Masiero, S.; Mateos-Nozal, J.; Ortega, O.; et al. European Society for Swallowing Disorders—European Union Geriatric Medicine Society white paper: Oropharyngeal dysphagia as a geriatric syndrome. Clin. Interv. Aging 2016, 11, 1403–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, C.L. History of the Use and Impact of Compensatory Strategies in Management of Swallowing Disorders. Dysphagia 2017, 32, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, J.; Butler, S.G.; Daniels, S.K.; Diez Gross, R.; Langmore, S.; Lazarus, C.L.; Martin-Harris, B.; McCabe, D.; Musson, N.; Rosenbek, J. Swallowing and dysphagia rehabilitation: Translating principles of neural plasticity into clinically oriented evidence. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2008, 51, S276–S300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuydam, A.C.; Rogers, S.N.; Brown, J.S.; Vaughan, E.D.; Magennis, P. Swallowing rehabilitation after oro-pharyngeal resection for squamous cell carcinoma. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2000, 38, 513–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Fernández, M.; Ottenstein, L.; Atanelov, L.; Christian, A.B. Dysphagia after Stroke: An Overview. Curr. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Rep. 2013, 1, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huckabee, M.-L.; Flynn, R.; Mills, M. Expanding Rehabilitation Options for Dysphagia: Skill-Based Swallowing Training. Dysphagia 2023, 38, 756–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speyer, R.; Sutt, A.L.; Bergström, L.; Hamdy, S.; Heijnen, B.J.; Remijn, L.; Wilkes-Gillan, S.; Cordier, R. Neurostimulation in People with Oropharyngeal Dysphagia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses of Randomised Controlled Trials-Part I: Pharyngeal and Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byeon, H. Effect of simultaneous application of postural techniques and expiratory muscle strength training on the enhancement of the swallowing function of patients with dysphagia caused by parkinson’s disease. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2016, 28, 1840–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, S.P.; Abdelhalim, S.M.; Jones, C.A.; McCulloch, T.M. Effect of Body Position on Pharyngeal Swallowing Pressures Using High-Resolution Manometry. Dysphagia 2018, 33, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, D.; Ashford, J.; Wheeler-Hegland, K.; Frymark, T.; Mullen, R.; Musson, N.; Hammond, C.S.; Schooling, T. Evidence-based systematic review: Oropharyngeal dysphagia behavioral treatments. Part IV--impact of dysphagia treatment on individuals’ postcancer treatments. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 2009, 46, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaziano, J.E. Evaluation and management of oropharyngeal Dysphagia in head and neck cancer. Cancer Control 2002, 9, 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inagaki, D.; Miyaoka, Y.; Ashida, I.; Ueda, K.; Yamada, Y. Influences of body posture on duration of oral swallowing in normal young adults. J. Oral Rehabil. 2007, 34, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bülow, M.; Olsson, R.; Ekberg, O. Supraglottic swallow, effortful swallow, and chin tuck did not alter hypopharyngeal intrabolus pressure in patients with pharyngeal dysfunction. Dysphagia 2002, 17, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuramoto, N.; Jayatilake, D.; Hidaka, K.; Suzuki, K. Smartphone-based swallowing monitoring and feedback device for mealtime assistance in nursing homes. Annu. Int. Conf. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. 2016, 2016, 5781–5784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matías Ambiado-Lillo, M. Impact of Head and Neck Posture on Swallowing Kinematics and Muscle Activation: A Systematic Review. Dysphagia 2025, 40, 1049–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagy, A.; Peladeau-Pigeon, M.; Valenzano, T.J.; Namasivayam, A.M.; Steele, C.M. The effectiveness of the head-turn-plus-chin-down maneuver for eliminating vallecular residue. Codas 2016, 28, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashford, J.; McCabe, D.; Wheeler-Hegland, K.; Frymark, T.; Mullen, R.; Musson, N.; Schooling, T.; Hammond, C.S. Evidence-based systematic review: Oropharyngeal dysphagia behavioral treatments. Part III--impact of dysphagia treatments on populations with neurological disorders. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 2009, 46, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahia, M.M.; Lowell, S.Y. A Systematic Review of the Physiological Effects of the Effortful Swallow Maneuver in Adults with Normal and Disordered Swallowing. Am. J. Speech-Lang. Pathol. 2020, 29, 1655–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, S.K.; Smith, C.H.; Newham, D.J. Surface Electromyographic Biofeedback and the Effortful Swallow Exercise for Stroke-Related Dysphagia and in Healthy Ageing. Dysphagia 2021, 36, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, G.H.; Kamarunas, E.; Mann, G.C.; Schmidley, J.W.; Robbins, J.A.; Crary, M.A. Effects of Mendelsohn maneuver on measures of swallowing duration post stroke. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 2012, 19, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilvashree, C.; Swapna, N.; Prakash, T.K. Impact of Effortful Swallow with Progressive Resistance on Swallow Safety, Efficiency and Quality of Life in Individuals with Post-Stroke Dysphagia: Analysis Using DIGEST- FEES and SWAL-QOL. Indian J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2023, 75, 2836–2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, P.; Peladeau-Pigeon, M.; Simmons, M.; Steele, C.M. Exploring the Efficacy of the Effortful Swallow Maneuver for Improving Swallowing in People with Parkinson Disease—A Pilot Study. Arch. Rehabil. Res. Clin. Transl. 2023, 5, 100276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCullough, G.H.; Kim, Y. Effects of the Mendelsohn maneuver on extent of hyoid movement and UES opening post-stroke. Dysphagia 2013, 28, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banda, K.J.; Chu, H.; Kao, C.C.; Voss, J.; Chiu, H.L.; Chang, P.C.; Chen, R.; Chou, K.R. Swallowing exercises for head and neck cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized control trials. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021, 114, 103827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.L.; Banda, K.J.; Chu, Y.H.; Liu, D.; Lee, C.K.; Sung, C.M.; Arifin, H.; Chou, K.R. Efficacy of swallowing rehabilitative therapies for adults with dysphagia: A network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Geroscience 2025, 47, 2047–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Speyer, R.; Baijens, L.; Heijnen, M.; Zwijnenberg, I. Effects of therapy in oropharyngeal dysphagia by speech and language therapists: A systematic review. Dysphagia 2010, 25, 40–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.S.; Hwang, N.K. Chin tuck against resistance exercise for dysphagia rehabilitation: A systematic review. J. Oral Rehabil. 2021, 48, 968–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winiker, K.; Kertscher, B. Behavioural interventions for swallowing in subjects with Parkinson’s disease: A mixed methods systematic review. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 2023, 58, 1375–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, S.; McAuley, D.F.; Walshe, M.; McGaughey, J.; Anand, R.; Fallis, R.; Blackwood, B. Interventions for oropharyngeal dysphagia in acute and critical care: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2020, 46, 1326–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govender, R.; Smith, C.H.; Taylor, S.A.; Barratt, H.; Gardner, B. Swallowing interventions for the treatment of dysphagia after head and neck cancer: A systematic review of behavioural strategies used to promote patient adherence to swallowing exercises. BMC Cancer 2017, 17, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Govender, R.; Smith, C.H.; Taylor, S.A.; Grey, D.; Wardle, J.; Gardner, B. Identification of behaviour change components in swallowing interventions for head and neck cancer patients: Protocol for a systematic review. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, N.; Teasell, R.; Salter, K.; Kruger, E.; Martino, R. Dysphagia treatment post stroke: A systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Age Ageing 2008, 37, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rethlefsen, M.L.; Kirtley, S.; Waffenschmidt, S.; Ayala, A.P.; Moher, D.; Page, M.J.; Koffel, J.B.; Blunt, H.; Brigham, T.; Chang, S.; et al. PRISMA-S: An extension to the PRISMA Statement for Reporting Literature Searches in Systematic Reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Health and Medical Research Council. NHMRC Additional Levels of Evidence and Grades for Recommendations for Developers of Guidelines. 2009. Available online: https://www.mja.com.au/sites/default/files/NHMRC.levels.of.evidence.2008-09.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Kmet, L.M.; Lee, R.C.; Cook, L.S. Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers from a Variety of Fields. 2004. Available online: https://ualberta.scholaris.ca/bitstreams/0e6c2b8b-7765-45bd-a4fa-143d13b92a00/download (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Guolo, A.; Varin, C. Random-effects meta-analysis: The number of studies matters. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 2017, 26, 1500–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borenstein, M.; Hedges, L.; Higgins, J.; Rothstein, H. Comprehensive Meta-Analysis; Biostat: Englewood, NJ, USA, 2014; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein, M. How to understand and report heterogeneity in a meta-analysis: The difference between I-squared and prediction intervals. Integrtive Med. Res. 2023, 12, 101014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; L. Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Begg, C.B.; Mazumdar, M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 1994, 50, 1088–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, R. The file drawer problem and tolerance for null results. Psychol. Bull. 1979, 86, 638–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumai, Y.; Miyamoto, T.; Matsubara, K.; Satoh, C.; Yamashita, S.; Orita, Y. Swallowing dysfunction in myasthenia gravis patients examined with high-resolution manometry. Auris Nasus Larynx 2021, 48, 1135–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ra, J.Y.; Hyun, J.K.; Ko, K.R.; Lee, S.J. Chin tuck for prevention of aspiration: Effectiveness and appropriate posture. Dysphagia 2014, 29, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vose, A.K.; Marcus, A.; Humbert, I. Kinematic Visual Biofeedback Improves Accuracy of Swallowing Maneuver Training and Accuracy of Clinician Cues During Training in Stroke Patients with Dysphagia. PM&R 2019, 11, 1159–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Don Kim, K.; Lee, H.J.; Lee, M.H.; Ryu, H.J. Effects of neck exercises on swallowing function of patients with stroke. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2015, 27, 1005–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, J.; Humbert, I. Impact of the Chin-Down Posture on Temporal Measures of Patients with Dysphagia: A Pilot Study. Am. J. Speech-Lang. Pathol. 2021, 30, 1049–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, S.; Steele, C.M. The Effect of Chin Down Position on Penetration-Aspiration in Adults with Dysphagia. Can. J. Speech-Lang. Pathol. Audiol. 2012, 36, 142–148. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, L.M.S.; da Silva, R.G.; Pedroni, C.R.; Garner, D.M.; Raimundo, R.D.; Valenti, V.E. Effects of effortful swallowing on cardiac autonomic control in individuals with neurogenic dysphagia: A prospective observational analytical study. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 10924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heslin, N.; Regan, J. Effect of effortful swallow on pharyngeal pressures during swallowing in adults with dysphagia: A pharyngeal high-resolution manometry study. Int. J. Speech-Lang. Pathol. 2022, 24, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, J.Y.; Shin, D.Y.; Kim, T.U.; Kim, S.Y.; Hyun, J.K.; Lee, S.J. Effectiveness of Chin Tuck on Laryngeal Penetration: Quantitative Assessment. Dysphagia 2021, 36, 1054–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyama, Y.; Sugimoto, A.; Hamano, T.; Kasahara, T.; Toyokura, M.; Masakado, Y. Proposal for a Modified Jaw Opening Exercise for Dysphagia: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Tokai J. Exp. Clin. Med. 2017, 42, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nagura, H.; Kagaya, H.; Inamoto, Y.; Shibata, S.; Ozeki, M.; Otaka, Y. Effects of head flexion posture in patients with dysphagia. J. Oral Rehabil. 2022, 49, 627–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terré, R.; Mearin, F. Effectiveness of chin-down posture to prevent tracheal aspiration in dysphagia secondary to acquired brain injury. A videofluoroscopy study. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2012, 24, 414–419.e206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaker, R.; Easterling, C.; Kern, M.; Nitschke, T.; Massey, B.; Daniels, S.; Grande, B.; Kazandjian, M.; Dikeman, K. Rehabilitation of swallowing by exercise in tube-fed patients with pharyngeal dysphagia secondary to abnormal UES opening. Gastroenterology 2002, 122, 1314–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, T.; Kumai, Y.; Matsubara, K.; Kodama, N.; Satoh, C.; Orita, Y. Different types of dysphagia alleviated by the chin-down position. Auris Nasus Larynx 2021, 48, 928–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terlingen, L.T.; Pilz, W.; Kuijer, M.; Kremer, B.; Baijens, L.W. Diagnosis and treatment of oropharyngeal dysphagia after total laryngectomy with or without pharyngoesophageal reconstruction: Systematic review. Head Neck 2018, 40, 2733–2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Speyer, R.; Cordier, R.; Farneti, D.; Nascimento, W.; Pilz, W.; Verin, E.; Walshe, M.; Woisard, V. White Paper by the European Society for Swallowing Disorders: Screening and Non-instrumental Assessment for Dysphagia in Adults. Dysphagia 2022, 37, 333–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MedTech Europe. In Proceedings of the 31st Congress of the Union of the European Phoniatricians, Prague, Czech Republic, 4–7 June 2025.

| Search Strategies |

|---|

| Embase: (swallowing/ OR dysphagia/) AND (chin tuck OR chin-tuck OR chin down OR chin-down OR head flexion OR neck flexion OR head tilt forward OR head tilt OR flexion of the head OR head rotation OR head-rotation OR head turn OR rotation of the head OR rotated head OR head back OR chin up OR head extension OR extension of the head OR head tilt OR tilting head OR side-lying OR side lying OR Mendelsohn OR supraglottic swallow OR voluntary airway closure OR airway closure technique OR airway protection technique OR airway protection maneuver OR airway protection manoeuvre OR breath-holding OR breath holding OR supersupraglottic swallow OR super-supraglottic swallow OR super supraglottic swallow OR effortful swallow OR hard swallow OR Masako OR Tongue holding OR tongue-holding OR tongue hold OR tongue-hold OR Shaker OR head lift) |

| PubMed: (“Deglutition”[Mesh] OR “Deglutition Disorders”[Mesh]) AND (“chin tuck” OR “chin-tuck” OR “chin down” OR “chin-down” OR “head flexion” OR “neck flexion” OR “head tilt forward” OR “head tilt” OR “flexion of the head” OR “head rotation” OR “head-rotation” OR “head turn” OR “rotation of the head” OR “rotated head” OR “head back” OR “chin up” OR “head extension” OR “extension of the head” OR “head tilt” OR “tilting head” OR “side-lying” OR “side lying” OR “Mendelsohn” OR “supraglottic swallow” OR “voluntary airway closure” OR “airway closure technique” OR “airway protection technique” OR “airway protection maneuver” OR “airway protection manoeuvre” OR “breath-holding” OR “breath holding” OR “supersupraglottic swallow” OR “super-supraglottic swallow” OR “super supraglottic swallow” OR “effortful swallow” OR “hard swallow” OR “Tongue holding” OR “tongue-holding” OR “Masako” OR “tongue hold” OR “tongue-hold” OR “Shaker” OR “head lift”) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Silvia, A.; Speyer, R.; Cordier, R.; Windsor, C.; Korim, Ž.; Tedla, M. Evaluating Behavioural Interventions for Oropharyngeal Dysphagia in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Swallowing Manoeuvres, Exercises, and Postural Techniques. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7180. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207180

Silvia A, Speyer R, Cordier R, Windsor C, Korim Ž, Tedla M. Evaluating Behavioural Interventions for Oropharyngeal Dysphagia in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Swallowing Manoeuvres, Exercises, and Postural Techniques. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(20):7180. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207180

Chicago/Turabian StyleSilvia, Adzimová, Renée Speyer, Reinie Cordier, Catriona Windsor, Žofia Korim, and Miroslav Tedla. 2025. "Evaluating Behavioural Interventions for Oropharyngeal Dysphagia in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Swallowing Manoeuvres, Exercises, and Postural Techniques" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 20: 7180. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207180

APA StyleSilvia, A., Speyer, R., Cordier, R., Windsor, C., Korim, Ž., & Tedla, M. (2025). Evaluating Behavioural Interventions for Oropharyngeal Dysphagia in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Swallowing Manoeuvres, Exercises, and Postural Techniques. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(20), 7180. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207180